The staggering effects and ethical quandaries of anthropogenic climate change frame every action and decision we human animals currently make. For those motivated and inspired by the making, contemplating, producing, and consuming of art, this circadian pressure is a consequence and a fact. In other words, art is existentially and essentially embedded within the interdisciplinary civics of our time—the concrete entanglements of the Anthropocene/Capitalocene.

Lisa E. Bloom author of Gender On Ice: American Ideologies of Polar Expeditions (1993), one of the first feminist works of visual culture/science studies/cultural studies, is a scholar who has long known and worked within this critical rubric. Her magisterial Climate Change and the New Polar Aesthetics: Artists Reimagine the Arctic and Antarctic was published by Duke University Press at the end of 2022. She and I met on Zoom with her long-time collaborator and coauthor Elena (El) Glasberg to discuss the implications of what they call the “new polar aesthetics.” The collaboration with Glasberg started in 2007 when they coedited with Laura Kay at Barnard College a special issue of the online journal The Scholar and Feminist on art, gender, and the polar regions in 2008. As you will learn from our conversation, the new polar aesthetics is “not meant to simply critique the reactionary masculinist culture of right-wing nationalism,” but in seven chapters, explores the “feminist, queer, postcolonial, and Indigenous artists and filmmakers” who “articulate ways of responding to the climate crisis that differ quite markedly from those of their Western masculinist counterparts” (13).

Thyrza Nichols Goodeve: Welcome Lisa and El. It is a pleasure to speak with you both about your book. Lisa, you are the main author, and El, you and Lisa collaborated on two of the seven chapters, so let’s begin with introductions of your histories as scholars on climate change, contemporary art, and the polar regions. Lisa, you have been doing interdisciplinary work since the 1980s when you and I met as students in the History of Consciousness program at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Lisa Bloom: Much of my writing over the last fifteen years brings the issues of gender, race, and colonialism, and the relation of the human and nonhuman to bear on the topic of climate change and contemporary art. In certain ways I have been thinking about social art history and feminist approaches since the days when I was an art history major at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, in the late 1970s, when I was fortunate to be exposed to these issues by my art history professor Judy Rohrer. I also thought about these questions when I trained to be a photographer at the International Center for Photography in New York City and received an MFA at the Rochester Institute of Technology and then the Visual Studies Workshop (VSW) in Rochester, which was a radical collective space that was in part publicly funded at the time. While there, as well as taking photographs, I started reviewing photography books for Afterimage. At that time, I was very much influenced by the feminist perspective at Afterimage when Catherine Lord and Martha Gever were editors. But the bigger shift happened when I attended a conference in 1984 at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign—which was one of the first big conferences on cultural studies and visual culture—through the Marxist Literary Group. It brought together some of the authors and photographers writing for Afterimage, such as Martha Rosler, together with Douglas Crimp, Craig Owens, Frederic Jameson, and Gayatri Spivak, among others. It was there that I saw it was possible to bring together my interest in visual studies—art history and photography and feminism—and gave me confidence to go to the History of Consciousness program. After the Urbana-Champaign conference I was inspired to study further and it was clear to me after the Visual Studies Workshop, which was really a critical studies program, that I couldn’t go to a conventional art history or American Studies program to study photo history or modern art history since feminism and critical theory weren’t being taught widely at that time in most doctoral programs.

TNG: Gender on Ice was your dissertation? You worked with Donna Haraway and James Clifford. How did the book manuscript evolve through your course work in Hist Con?

LB: In the mid 1980s when I was taking graduate classes with James Clifford, Paul Rabinow, Frederic Jameson, Hayden White, Donna Haraway, Stephen Heath, and Teresa de Lauretis, I was reading the writing of my professors as well as the work of Edward Said and Michel Foucault in my graduate seminars. At that time, I also participated with other graduate students at the History of Consciousness Program—Deborah Gordon, Chela Sandoval, Caren Kaplan, Ruth Frankenberg, Lata Mani, Thyrza Goodeve, among others—in what was then called the Group for the Critical Studies of Colonial Discourse, which also had its own journal Inscriptions (1985–94). In the journal’s beginnings there was a strong focus on how the history of modern imperialism bears directly upon the condition of women and relations of gendered power. The focus of my dissertation evolved quite organically out of this context since it linked polar exploration narratives to the interdisciplinary study of gender and to the key concepts of colonialism, modernity, science, and nationalism.

TNG: Two out of the seven chapters of The New Polar Aesthetics are coauthored with you, El. You come out of literature and American Studies and are the author of Antarctica as Cultural Critique: The Gendered Politics of Scientific Exploration and Climate Change (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). Lisa’s book must have been quite influential.

Elena Glasberg: I had read Gender on Ice in grad school at Indiana University. I come from American Studies and even today I wouldn’t claim to be anything more than a cultural studies literature-based American Studies scholar. Early on I was interested in writing about Poe, so it was The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym that got me into Antarctica, which got me out of American Studies, even if I’m still in American Studies. But I met Lisa at The Scholar and Feminist conference on the Polar regions at Barnard in 2008.

TNG: This was a watershed moment for you both?

LB: Yes, the invitation to be a coeditor for the special journal issue of The Scholar and Feminist as well as the international conference we put together at Barnard to launch the issue during the International Polar Year in the fall of 2008 were both extraordinary events for me because it really brought me back to Gender on Ice, which by that point I had moved away from. The interdisciplinary nature of that book made it very hard for me to get a job when the book came out in 1993. I had to switch my focus to art history and photo history, which is where I have the kind of disciplinary depth that I needed in order to teach, get fellowships, and have institutional support. But at that point, my work had been so transformed I couldn’t approach either field in the traditional way. So, that was when I published With Other Eyes: Looking at Race and Gender and Visual Culture (University of Minnesota Press, 1999) where I published people like Jennifer Gonzalez and Sean Smith who then became well-known scholars in art history and photo history. But it was thanks to El Glasberg and Laura Kay in 2008 who invited me to coedit this special issue that I discovered how my book had taken off in different parts of the world within the context of climate change and so it returned me to that work. Frankly, I was pretty surprised.

TNG: With Gender on Ice, you inadvertently invented a discipline, didn’t you?

LB: When Gender on Ice was published there was virtually no feminist scholarship on either of these areas. Moreover, although the academic world in Canada, the Scandinavian countries, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand have given rise to a highly critical, revisionist attitude toward Arctic and Antarctic explorers and their writing since the 1970s, US scholars did not show an equally critical scholarly interest in the Arctic or the Antarctic until the late 1990s and as a result, Gender on Ice’s readership was primarily outside the US since the poles were not considered a subject of vital concern then. In certain ways the book’s popularity stood closer to the more international scholarship on these regions, but it did help to create more of a focus for feminist perspectives in the growing field of polar studies and Arctic and Antarctic Studies, in fields such as art, literature, geography, and polar science. Now that there is a redefining of the globe and the polar areas are coming into daily circulation even in the US, the book has since become highly cited because of the growth of scholarship and programs abroad focusing on the Arctic and Antarctic and the wider interest in the book’s early intersectional feminist approach.

TNG: Climate Change and the New Polar Aesthetics offers a radical thesis: that art is not just supplementary to the discourse on climate, but, as the title says, is about “Artists [who] Reimagine the Arctic and Antarctica.” In fact, Lisa, you situate imagination as essential to the politics of this new aesthetics and you discuss the way art has become data or evidence in climate change debates as well as how much work involves blurring the line between fictional and documentary formats and science fiction. Here your book aligns with McKenzie Wark’s Molecular Red: Theory for the Anthropocene (Verso Press, 2015) and Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press, 2016) where fiction and imagination are essential to politics. Your book covers so much territory, please discuss the structure. For instance, how you privilege intersectional feminism as well as Black and Indigenous perspectives at the outset.

LB: That is right, it is important to see the artwork in the book as crucial to expanding our political imagination of how we see these regions and climate change outside of mainstream media depictions that feature apocalyptic spectacles of distant melting ice and desperate polar bears. Artists in the book link regional climate change to gender, race, the relation of the human to the nonhuman, questions of territory, knowledge production, and empire. They shake viewers out of routine assumptions about the natural world and invert the tourist gaze using strategies borrowed from postmodernist art, science fiction, speculative fiction, and the gothic horror genre. Indigenous filmmakers widen our purview to think of the entangled ecological dimensions of the Arctic, drawing on traditional Indigenous knowledges and on more experimental approaches. The intersectional framework goes beyond naming categories to understanding the complex entanglement of nature and culture in the context of a modern visual tradition still influenced by the masculinist imagery of sublime wilderness from the heroic age of exploration (1897–1922) that nevertheless reemerged in more modern forms to justify the imperial expansion that is accelerating the extraction of oil, gas, coal, and rare earth materials.

TNG: This relates to how you chose work that challenges and offers alternatives to the aesthetics of the distanced sublime and the white male heroics you discussed at length in Gender on Ice. I’m thinking of Anne Noble’s restaging of the archetypal photographs of Herbert Ponting’s Barne Glacier from 1911, or Judit Hersko’s Pages from the book of the Unknown Explorer or Connie Samaras’s feminist approach that focuses on the ordinary and every day in Underneath Amundsen-Scott Station and Domes (2005) and South Pole Antennae Field (2005), and most significantly, the use of the female voice in Ursula Biemann‘s Deep Weather (2013).

LB: Yes, as you point out, feminist art works by Anne Noble, Connie Samaras, and Judit Hersko on Antarctica, challenge an aesthetics of the distanced sublime from Romantic aesthetics and its roots in European Universalism: the idea of a white and male oriented domestication of nature. For them, representing climate change by sublime aesthetics often comes wrapped in a colonial nostalgia for an earlier image of Antarctica as a polar sublime landscape from the heroic age of exploration (1897–1922) in the years bracketed by the deaths of its defining British celebrities, Robert Falcon Scott, and Ernest Shackleton. Some of these well-known photographic images of Antarctica from that period by photographers like Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley mythologized the idea of Scott and Shackleton’s expedition as a heroic life and death struggle—one of the more common narrative tropes of Arctic and Antarctic exploration narratives and art. In Ponting’s Barne Glacier, the glacier dominates to such an extent that the figure in the landscape is tiny by comparison, easily engulfed by the vast icy landscape. For example, in Frank Hurley’s Blizzard at Cape Denison from 1912 in which silhouetted figures struggling against the wind and cold are superimposed on a windy Antarctic landscape to illustrate the terror associated with the powerful, forbidding climate.

Anne Noble’s Barne Glacier, Antarctic Centre, Christchurch, 2003 (2003) references and comments on these iconic images of sublime wilderness from the heroic era that show the inhospitable space of the Antarctic as a male testing ground in which isolation and physical danger combine with overwhelming beauty. Substitution and humor are central to Noble’s postmodern strategy, representing Antarctica and contemporary tourism in immersive environments such as in IMAX theaters and theme park–type exhibitions both outside and within Antarctica. In Barne Glacier, Noble presents two dummies dressed in National Science Foundation standard-issue extreme-weather gear standing before a panoramic photograph of the Barne Glacier in an Antarctic-themed indoor entertainment center in New Zealand. Noble’s photographs use beauty and space in less conventional ways by reversing Ponting’s use of composition. Her image, in contrast, is tightly framed and almost claustrophobic, robbing the setting of its epic character. While the photographic beauty of her images is central to their meaning, she is also asking us to rethink the way the sublime can be experienced in an artificially simulated landscape environment, creating an uncanny commentary about the contradictions between the Antarctica visualized in Hurley’s and Ponting’s photographs and the kitsch aesthetic of sublime wilderness now produced in indoor settings such as the Antarctic Center in New Zealand, where she took this photo. The point for Noble is that what is sold in these contemporary tourist images is not global warming or the threat of pollution but the promise of Antarctica’s mythical past, in which icebergs, glaciers, penguins, whales, and white male heroes dominate and define the horizon and white man’s endurance.

On the other hand, Judit Hersko, like Noble, searches for new ways to tell stories about the invisibility of women’s historical place in polar exploration narratives but in her case, she connects this to the invisibility of the significant labor and herculean role of tiny lifeforms like the sea butterfly and the sea angel in the Antarctic oceans. In this way, her work brings together the feminist question of the scale of the personal to the nonhuman to acknowledge the connectedness and relationality of the human and the more than human. That such small planktonic organisms are considered the canaries in the coal mine when it comes to the state of the oceans in the era of climate change is at odds with a world where large mammals such as polar bears are preferred as the icons of anthropogenic climate change.

For Samaras and Hersko, their more intimate encounters with the landscape mean bringing in the physical relationships of the human and nonhuman and the interconnection of natural systems to highlight the sense of dislocation involved in living in such an extreme environment that is already in a state of slow collapse. In her photographs of Antarctica’s built environment, she uses science fiction and horror narratives to focus on the ordinary and every day but injects something more unsettling and unearthly into otherwise neutral and objective images of mostly anonymous industrial structures, as in her photograph Underneath Amundsen-Scott Station or in her South Pole Antennae Field (2005), an image of an empty Antarctic landscape that dwarfs tiny radio antennae standing as the only sign of human habitation. Samaras’s work is also not about heroic masculinity but about something much more displaced, related to both her positionality as a woman and the placelessness of the sites that she photographs. Her detailed focus on the everyday brings us back to our senses and, in its focus on Antarctic architecture (both new and old), counters romanticism and fantasies.

EG: Here I’d like to discuss Ursula Biemann’s video Deep Weather (2013) and her use of the whispering female voice. Deep Weather is about the dynamic political geography of climate change, in particular the impact of the carbon released from the tar sands in Alberta, Canada, on postcolonial South Asia, specifically, the poor and marginalized in Bangladesh. For Biemann, the whispering in Deep Weather starts to take on another dimension as it becomes an insinuation. In other words, how we have insinuated ourselves into earth systems, and these anthropogenic systems are now insinuated into everything that we do, every thought that we have. So, I think that’s also the effect of that voice. It wants to bother you; it wants to say that it’s you who are the problem.

TNG: Excellent point, El. Would you discuss your work on Antarctica and how this differs from the history of the Arctic regions and what this means for artists and activists working on climate change?

EG: My work was inspired by Poe’s “unfinished” 1838 novel Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, a strange and formerly disparaged seafaring pastiche that sailed from New Bedford and ended—most inconclusively—at the then completely unknown South Pole. I foundered for a time trying to write a literature-based account of US fantasies of empire, when a National Science Foundation grant (American Studies programs were not interested in the South Pole) landed me in the actual Antarctic, and everything changed. My book ended up engaging Google Earth, fine art photographers including Anne Noble and Connie Samaras, and early twenty-first-century corporate eco-advertising. I will never forget that one of the ironies of studying Antarctica is the fact that I actually went there. In other words, that’s when everything changed for me because I wasn’t doing Poe and studying national projection and fantasy anymore but was encountering the material ice and the art that deals with it. The real problem is that I was/we are there. It’s not good that humans are there and we’re building all over the ice; and the ice would take it back very quickly if we left.

TNG: Were you there when Joyce Campbell, the author of the cover photo used for Lisa’s book, was there?

EG: No, I think she actually went down the year after. I didn’t meet her there. I was down at the same time that Anne Noble and Connie Samaras were there. We were all supported by the NSF Artists-in-Residence program on a similar junket. But none of us should have been there.

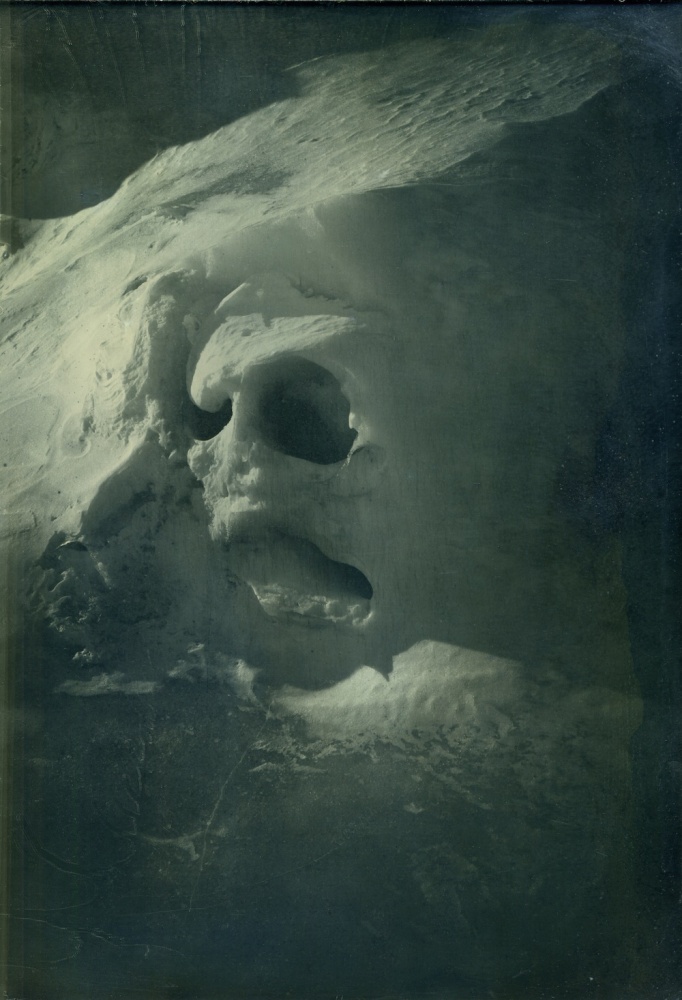

TNG: Let’s talk about that cover image—I hear it has been controversial.

EG: People have been responding to that image and reading it very dead-on—that it’s sentimental and is referencing the Gothic which has a bad odor.

TNG: I would never have thought of this cover as anything other than powerful and moving.

EG: But the arguments are that it is anthropomorphizing; a staged projection. And that she’s working with obsolete photographic technology, while, in fact, she was actually there in Antarctica, lugging heavy obsolete photographic equipment up a glacier with crampons on her boots. But none of that is directly apparent in the image.

TNG: That would be an entirely different work! It’s a daguerreotype photograph. It’s indexical so the image of the groaning dying face emerging from the ice is an accident of captured perception or projection. It operates like the best of early Surrealism—like Dali’s idea of critical paranoia—or Breton, that you find the convulsive marvelous in the world. It’s not like it’s a drawing of a sad iceberg, now that would be sentimental.

EG: Yes. But the image also indexes the gothic and goes straight for your emotions. I mean, the ice doesn’t actually have emotions. It’s not real, right? People just see a landscape that’s focusing on this funny little distortion that looks anthropomorphic, like a skull. They can’t perceive the quotes around the image, or they refuse to feel any emotion but the heroic when it comes to contemporary Antarctica.

LB: I have this book on Joyce Campbell [On the Last Afternoon: Disrupted Ecologies and the Work of Joyce Campbell, Sternberg Press, 2019]. It’s a pretty thick catalog and you can see John Welshman from UC San Diego is the editor. It includes a piece by Geoffrey Batcheon, who we knew at History of Consciousness. He hates this image of hers, likening it to Caravaggio’s Medusa (1596) or Edward Munch’s The Scream (1893) that has entered popular culture. He prefers instead Campbell’s vacant daguerreotypes to the ones that she actually made and exhibited, as he writes in his 2020 article aptly titled “Nothing to Photograph”: “Most powerful, for me at least are the plates where nothing at all was registered, the ones that Campbell herself considered to be not sufficiently photographic to be worthy of exhibition. A photograph that denies us the comfort of perspectival rationality, a photograph that channels the nothingness that haunts the whole history of Antarctic photography . . . a photograph that is unable to signify anything other than its own erasure: What could be a more terrifying prospect than that?”

For Batchen, Joyce Campbell’s ice ghoul is an exemplar of kitsch. By saying there is “nothing to photograph,” he slaps the artist in the face as well as minimizes what a strong statement about climate change the image of the ghoul is. I don’t think grand modernist gestures like vacant daguerreotypes can suffice alone. Rather, climate change is precisely like the gothic that haunts us every day through repetitions of cause and effect but is always there in a liminal and uncanny presence, as Thyrza points out, operating like early Surrealism. This haunting is also conceptual and corporeal and should be embraced in contemporary art as part of the ecological uncanny. This concept is more capacious and enables us to reimagine through art our current ecological condition and how that operates through affect.

TNG: Not surprising, but I knew Batcheon when we were at the Whitney ISP, before I entered the History of Consciousness Program. This image is, yes, everything I think the Whitney Independent Study’s Program/Ron Clark’s doctrine of “art is critical in the most overt sense or it is not art” would find uncomfortable. Now I see why you say it has been critiqued as sentimental.

LB: It’s too kitschy for him.

EG: If you had an image from Roni Horn’s Library of Water—a work also written about in the book—on the cover nobody would give you any trouble, right? Roni Horn’s work is much more abstract even when there are people involved. She’s a sculptor, although not primarily because she works a lot with photography, but I would argue even her photographs are sculptural. She is always sculpting—she has a drive to control and to create complex environments that are parallel versions of earth environments. Understatement and containment are her trademarks. She’s not campy at all. You can distract yourself with a lot of her work’s formal beauty. Whereas Campbell’s image is a screaming skull. She’s waving a flag: “Dare to try to transcend the resistance to the horror of what we’re facing,” which is not just the degradation of the environment, but we’re at the point where we can see our earth turning into something that is out of balance. One difference between Horn and Campbell is Horn is willing to be misunderstood; her work is grand enough to contain even misdirection.

TNG: Which is the point and power of art. But come to think of it, this is the power of activism as well. This makes me think of the notion of art as data that you both discuss in the section titled “Archives of Knowledge and Loss.” Lisa, why don’t you discuss Subkankar Banerjee, Annie Pootoogook, and Andrea Bowers and how their work serves as data.

LB: This section is not only about how new polar art practices have begun to change our perceptions of the slowly unfolding catastrophes of melting ice and thawing permafrost but also about how artists work with Indigenous communities to make collective interventions that shift the very boundaries of art and visual representation. That makes us focus more on what forms they might take, what effect they might have, and how they unexpectedly might be read as meaningful “alternative” environmental data. Subhankar Banerjee’s landscape photography centers Indigenous presence and philosophies of the land in his images of animal and bird migration patterns in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, challenging assumptions about the Arctic. The late Annie Pootoogook also created a visual archive of Indigenous land, but one largely focused on inanimate objects and small groups or lone human subjects within built environments. Yet her depictions underscore how colonial dispossession can reveal itself through the way climate-led social disruption enters the sphere of subjective life of Indigenous peoples. Andrea Bowers’s 2009 work rememorializes the struggle over the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 and its incomplete cleanup, not from a scientific perspective, but from the point of view of both local Indigenous and white community members who have had to live with the damage over generations. Her work is a dark commentary on how insubstantial and incomplete demonstrations and protests are and how work for social change is often forgotten and erased by the inevitable next catastrophe. She is interested in representing what Banerjee calls “long environmentalism,” in the case of an environmental engagement that has lasted a quarter century and the way it has created a culture and history of its own.

TNG: So here one sees the connection, and necessity of, specific activist events that you include.

LB: Some of the artist-activists in the book like Liberate Tate and Platform London have made important contributions to activist feminist climate art, particularly the performance License to Spill (2010) that was the first protest in a six-year campaign of interventions at the Tate objecting to the cultural promotion by an oil company. The replication of an “oil” spill at Tate Britain by women performers who used bouffant dresses with handbags and high-heeled shoes as props employs satire to underscore their anger at the corporate elite’s greenwashing, which minimizes the damage caused by environmental pollution or, in more extreme cases, even makes them appear environmentally friendly. The Liberate Tate performance drew direct links between the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig and the corporate sponsorship by BP of art and culture production in London; and it was performed at Tate Britain at the same time as worldwide audiences were following the ruinous Deepwater Horizon oil spill through online video feeds. Ironically titled License to Spill, the group’s reenactment comprised two fake “oil” spills, one inside and the other outside Tate Britain, to disrupt the Tate Summer Party, which was intended to celebrate twenty years of BP’s support.

TNG: This play on spills and the relative degree of damage is about issues of scale which art and activism, again, are particularly good at interrogating. I think of Edward Burtynsky’s photos, which are criticized for their beauty yet are so incredibly articulate. I mean, it is the scale of the devastation that is so staggering.

LB: I’m glad you brought it back to Burtynsky because the issue of scale is incredibly important to the power of activism as a counterattack. I want to defend Burtynsky who gets a lot of criticism for aestheticizing the monumental scale of the oil industry and its devastating effects. But I feel like that’s really the power of his work. He depicts this huge network of the oil industry that extends beyond the Arctic and the oil rigs to the huge network of infrastructure from the oil industry—which includes junkyards and motorways—in the catalog for his exhibition Oil at the Corcoran Gallery in 2009.

TNG: Exactly. While Biemann uses cinematic montage to connect the environmental and colonial catastrophe of the Tar Sands in Alberta, Canada, with Bangladesh, Burtynsky’s photographs register the destruction within one image. Biemann is talking precisely about the scale of catastrophe across noncontiguous distances. You couldn’t take a photo showing evidence of the connections linking Alberta to Bangladesh except by satellite, and that isn’t going to make much of an impact.

LB: But at the same time, I argue that even critical anticapitalistic aesthetics such as Burtynsky’s can evoke disengagement, apathy, and dread.

That is why I also criticize his work because his aestheticizing absolutely terrifies us and makes us feel we’re incapable of attacking this industry because it’s so massive and monumental. It’s very hard to go up against this industry physically, verbally, and politically. And that’s why I contrast Burtynsky with the other actions by sHell No! and Idle No More who pursue aesthetic strategies very different from the terror and paralysis of Burtynsky’s industrial sublime. The activist media strategy of Idle No More pit the staggering scale of the drilling rig against kayakers to play up the heroism of the protesters, whose efforts were met with success four months later, when Shell announced in September 2015 that it would abandon Alaskan Arctic drilling.

TNG: Which is where Indigenous perspectives and resistance is so important. The statistics on the effect of Indigenous resistance to oil and gas projects in Canada are astounding—something like a 25 percent decrease in emissions.

LB: That is not surprising given how successful Idle No More (founded in 2012 in Saskatoon, Canada, by four Indigenous women and one non-Indigenous ally) have been inchanging the social and political context in Canada and beyond. So too with the Arctic Inuit women activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier, who movingly demanded “the right to be cold.” Like the women who founded Idle No More, Watt-Cloutier has been instrumental in shaping an environmental justice campaign and has been widely recognized for suggesting that climate change is a matter of both Indigenous and multispecies survival.

EG: There’s one thing about Arctic communities that the whole world should be learning from, and that is that they are relatively small. They have not peopled the earth and they have not spread. They have historically had small numbers and they leave a small imprint. The icy environments are not lush so there’s going to be a different kind of growth pattern on it naturally. They live with a sense of environmental balance. That’s the thing that you should do as a human being. And this is also about the need to create more art. You know, always just create more stuff, market more markets. But there’s one thing I know about ice, it is a natural barrier and limits all manner of growth. It gets you to limit how much you’re going to make so you will be able to support it.

TNG: Your book is getting attention because it’s not just about the dystopic. It makes me think of Margaret Atwood’s online course, Practical Utopias. Discuss the positive, the real differences that art and activism have made. What are key examples in your book?

LB: Certainly, there are successes from the actions of the artist-activists I write about who aim at holding Western art, natural history, and science museums to account for their complicity, through the solicitation and acceptance of corporate sponsorship, in enabling climate change and perpetuating the colonial narratives that underlie it. The work of activist artists such as Liberate Tate became a model for future artist-activists and in the end the Tate did stop taking money from BP. Not an Alternative/The Natural History Museum’s protest Expedition Bus, 2015 did manage to get David Koch off the board of the Museum of Natural History before he died. Activist groups like Idle No More and sHell No’s Protest over Arctic drilling in Seattle did, in fact, stop Shell from drilling for oil in the Arctic.

What made all these works successful in part is that each specifically attacked the source of the problem, and they also had a demand directed at the institution itself which was also important.

Subhankar Banerjee’s landscape photographs reframed the way we visualize the Arctic National Wildlife Reserve (ANWR) over a twelve-month period and helped Democrats in the Senate stop Republicans from opening ANWR from oil drilling since his work disproved their argument of the region as a frozen wasteland year-round in 2002. Senate opponents of drilling, such as then senator Barbara Boxer (D-CA), used Banerjee’s large-format color photographs of calving caribous, migrating birds, snow geese with chicks, and frolicking polar bears living in and migrating through the refuge to illustrate the irreparable damage that would occur to a region that has been called America’s Serengeti were it to be opened to drilling. Consequently, the vote to open the refuge to drilling that year failed, fifty-two to forty-eight.

But Banerjee’s success came at a cost—his photography was censored a year later by the Smithsonian. This unusual move took the form of Banerjee’s captions being edited by the institution and suggests the power that Big Oil had in the United States during the administration of George W. Bush; artwork was as vulnerable to censorship as reports that ran counter to the administration’s interests.

TNG: Let’s go back to the art world. A dilemma that comes up when teaching is, of course, the huge carbon footprint of most art making and the toxicity and lack of sustainability of traditional art supplies, not to mention the waste and extravagance of jetting about and organizing international biennials and art fairs.

LB: I wonder how the emergent conversations about what kind of world we want to live in now and in the future will translate into a rethinking of many of these unsustainable approaches to art. This is especially important as it becomes increasingly obvious that the ecological catastrophe resulting from climate change has entered our horizons and is not just happening at a distance in the polar regions. That should include thinking about future strategies towards more ecologically responsible artistic frameworks in the art world at large. Your comment about flying to art fairs and international biennials makes me feel that the message is not getting through and that we need to insist on forms of sustainability where people are mindful of taking care of themselves and of each other. Remember that the opening at the Venice Biennale this year was a big super spreader event, where many museum curators and staff who attended came down with Covid.

I recently looked at the end of the year’s best exhibits of 2022 in Artforum, which I don’t usually read because it is so overwhelmed by ads. What was startling to me was the absolute absence of interest in exhibits on ecology and climate change. No special mention was even made of the Venice Biennale The Milk of Dreams, which was informed by new materialist thinking that focused in part on the ecological interconnectedness between the human and the more-than-human. Also absent was the series of art-related actions by young climate activists who targeted famous artworks at major museums around the world in 2022 to highlight the need for governments and institutions to stop subsidizing fossil fuel companies.

Hyperallergic is one of the few art publications in the US that did address the climate activists at the end of 2022. Hrag Vartanian reminds us that despite the outrage by museum leaders and their conservative allies over these actions, the activists did not damage any of the art during their protests and, in fact, chose prominent artwork that had protective glass covering the paintings. What Vartanian doesn’t mention is the urgency of rethinking and reimagining human activity as well as how art might play a role as a driving force in our response. As the urgency of the climate crisis has become increasingly obvious it has also become a serious challenge to institutions that operate in the public sphere of public accountability to find a way to address these issues of our times.

TNG: Have you seen the exhibition no existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria at the Whitney? It’s about the confluence of the ravages of imperialism and capitalism, of stateside America’s egregious attitudes and treatment of Puerto Rico regarding debt and the climate crisis after Hurricane Maria. It’s been recognized as one of the best shows of the year even though it just went up in November.

LB: It is always good news when certain museums like the Whitney buck the trend occasionally and want to see themselves as forums for debate and actions that impact society at large, but the lack of real dialogue, conversation, or effort to make a green transition in these institutions, over many years overall, has been really distressing. I’ve been writing on these issues for fifteen years and during this time I have found very little interest in work that complexly focuses on climate change in museums that indicates that they are taking the foreboding climate collapse seriously and are addressing it aggressively.

I would also like to add that some forms of climate activism have been more successful than others in holding Western art museums accountable for their complicity, through the solicitation and acceptance of corporate sponsorship, in enabling climate change and perpetuating the colonial narratives that underlie it. I find the kind of art activism I write about in the book targeted at institutions and oil companies, not at artworks per se, more productive and generative in accomplishing these goals. It nevertheless irks me that museums must be forced by activists to become accountable to their publics. Why should the burden be put on the younger generation to make museums take the climate crisis seriously in relation to their own practices? Shouldn’t environmental sustainability and engagement with these serious issues be part of their mission statements as well as showing us that the arts could play a driving role in our response to the climate crisis?

TNG: You are right—the work needs to be done at the level of the rethinking/redoing of museum mission statements and practical real-life decisions that reduce museum and art world carbon footprints, decrease toxicity, challenge environmental racism, and supports art that aids in land claim restitution, anticolonialism, and communal as well as environmental remediation.

LB: There is another point I wanted to make. Although I haven’t yet seen Laura Poitras’s film All the Beauty in the Bloodshed about Nan Goldin, I did visit a big exhibit of Nan Goldin’s at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in November of 2022. While I respect Nan Goldin as an artist and an activist involved in community action, I’m uncomfortable with the way she has been singled out as an artist who has somehow single-handedly confronted the Sacklers, whereas her activism at the Guggenheim was in collaboration with her activist group Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (P.A.I.N.). Together they were fighting the outsized influence that members of the Sackler family, who owned Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, had on the art world. As a group they were incredibly effective at getting art museums to remove the Sackler name. Similarly, her earlier work on AIDS was also more collective and collaborative. For example, her seminal work, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is an intimate portrait of both the artist herself and a community that wrestles with addiction. It is important to point out that much of climate activism is also more collective and has roots in older models such as ACT UP. With Golden and Sackler, I wonder if we’re back to the individual artist as genius that is now turned to include the artist-activist. This reminds me of the outsized credit Judy Chicago received for Dinner Party (1979)—an icon of feminist art—when the work was a vast collaborative effort that involved hundreds of women artists and ceramists who contributed so much time and effort to the project. But it was Judy Chicago personally who has (apparently, unwillingly) made an international reputation from it. Since much of the important artwork on the climate crisis is also collaborative, there needs to be more thought given to how museums credit contributors in collaborative projects, especially in the art world where there is an entrenched star system as well as a longstanding tendency to elevate a single artist as sole genius and erase the contributions of others.

TNG: This brings up an aspect of the book I find so moving—how The New Polar Aesthetics models, performs, and offers a history of collective and collaborative work not just between you and El but also between your own scholarship and art. For instance, when you wrote Gender on Ice in 1993, Isaac Julian was inspired by your research on Matthew Henson to make True North, which you then write about in The New Polar Aesthetics in 2022.

LB: Yes, besides The Scholar and Feminist special issue, Isaac Julien’s True North was another reason that I decided to return to this earlier work and consider updating it in relation to the present. More recently, I’ve been fascinated by the way artists Isaac Julien and Katja Aglert interpreted my earlier writings in their more recent work. Neither of these artists started out as collaborators but now they are.

Chapter two of the book, “Reclaiming the Arctic through Feminist and Black Aesthetic Perspectives,” focuses on their art practices in the Arctic. The failure of imperialist heroism is the subject of Julien’s epic multiscreen immersive installation project True North (2004–08), which returns us to heroic US Arctic exploration narratives and their myths more than a hundred years after Robert Peary’s expedition. It is told from the vantage point of the African American polar explorer Matthew Henson, whose own witnessing authority and claims to the 1909 “discovery” of the North Pole were consistently written out of the script by white polar explorer Robert Peary. Julien’s True North takes poetic license, restructuring Henson’s story to dismantle the homophobic regimes of imperial masculinities. It draws from the documentary genre, historical documents, and nonfiction material and is heavily research based.

Katja Aglert’s multimedia installation project Winter Event – Antifreeze (2002) also explores white heroic masculinity and nationalist failure in the past and its recuperation and rehabilitation in the present not as a source of admiration or esteem but as a destructive act. Inspired by feminist scholarship and the work of Fluxus, her work (which was also turned into an experimental opera) draws on the photographic and media history of Svalbard but also uses repetition, performativity, and dark humor as strategies. Her self-presentation is deliberately modest and self-conscious, in contrast to the narrative of the lonely white male hero or artist. Through these strategies she deliberately sidelines images of the region’s beauty, with the result that the scenery often seems more modest. This is also evident in Aglert’s video in which she stands in front of various Arctic landscapes, always near a shore, holding melting ice in her bare hand. Like Anne Noble’s and Connie Samaras’s work on Antarctica discussed earlier, Aglert’s work is deliberately antiheroic in her use of and commentary on documentary.

It’s really exciting for me to see my earlier writing have an impact on artists that I have admired and then have a chance to write on how they are taking their work in important new directions seeking to widen considerations of the environment as it intersects with social, political, and cultural realms.

TNG: These are examples of the ongoing and consequential conversations that interdisciplinarity and collaboration have opened between scholars, writers, activists, and artists. It makes me think of Max Liboiron’s extraordinary book, Pollution Is Colonialism (Duke University Press, 2021)—a book that has influenced me a lot—it is at once experimental science, and a practicum on anti-colonial writing and theory. Liboiron is a Red River Métis/Michif scientist raised in Lac la Biche, Treaty 6 territory. They are an Associate Professor in Geography and formerly the Associate Vice President (Indigenous Research) at Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, who works on plastic pollution in Nova Scotia. The book is a terrific enactment of decolonizing science studies and academic scholarship in general. For instance, the footnotes are a serious critique of academic protocols of hierarchy. They are a virtuoso send up of the pomposity and elitism of the academic voice in the way David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest or Mark Danielewski’s House of Leaves are, but hers is within the context of science practiced from a feminist, anticolonial, and Indigenous perspective. The footnotes are conversational and situated—Liboiron uses them to shout out to friends and scholars to acknowledge, call out, and thank but at the same time she situates everyone in relation to their specific Indigenous and settler histories. It reminds me of what you and I learned early on with Donna Haraway, how in that first cyborg essay, she quotes her students and brings them in and how she continues to write from and through her oddkin community to this day. The New Polar Aesthetics is suffused with this. I was moved by your conclusion, Lisa, when you write, “The new polar aesthetics is activist, progressive, authentic, and earthbound (humble and rooted in the ground) and often done collaboratively with local and international publics in mind, without the goal of monetary gain. Such generous and generative art plays a fundamental role in connecting and empowering the transnational climate movement. With its focus on planetary survival, it also broadens our understanding of climate breakdown to create new knowledges and networks,” and I love that at this point you choose to end by saying, “which I and Elena Glasberg hope will support old and recent forms of collaborative, participatory, and activist climate art.”

EG: Yes, the issue is that climate change requires collective work on so many levels—through activism, science, art, and critiques of colonialism and capitalism. The change that people want is outside the art world, changing the substrates of the way we use fuel and fuel art.

TNG: Exactly—would you say then that the new polar aesthetics is ultimately about a political practice?

EG: Not necessarily, but the new polar aesthetics can’t just be from the art world because the art world can absorb all sorts of critiques. Melted ice can become artfully captured. But an actual melted glacier escapes art’s framing.

LISA BLOOM is the author of Climate Change and the New Polar Aesthetics: Artists Reimagine the Arctic and Antarctic (Duke University Press, 2022) and many feminist books and articles in art history, visual culture, and cultural studies, including Gender on Ice: American Ideologies of Polar Expeditions (University of Minnesota Press, 1993) and Jewish Identities in American Feminist Art: Ghosts of Ethnicity (Routledge, 2006), and the editor of With other Eyes: Looking at Race and Gender in Visual Culture (University of Minnesota Press, 1999). She has been a researcher at numerous University of California campuses over the years, including the University of California, Berkeley, where she was a scholar-in-residence at the Beatrice Bain Research Group in the Department of Gender and Women Studies.

ELENA (EL) GLASBERG specializes in places without people and people without place, teaching and writing at American University in Beirut, Princeton University, Duke University, and California State University, Los Angeles, before arriving at NYU’s Expository Writing Program in 2011. Glasberg’s is the author of Antarctica as Cultural Critique: The Gendered Politics of Scientific Exploration and Climate Change (Palgrave, 2012). Her writing has appeared in The Journal of Popular Music Studies, Journal of Historical Geography, and Women’s Studies Quarterly. Glasberg’s new project is Swamp Music: Bob Dylan’s Subterranean America, a materialist sounding of the unstable and mysterious landscapes at both the center and edges of US cultural imaginaries.

THYRZA NICHOLS GOODEVE is a writer, editor, interviewer, and educator. From 2017–19 she was the senior art editor of The Brooklyn Rail. She is writing a book about Yvonne Rainer’s influence on her generation and editing Workstyles of Mildred Lane with Morgan J. Puett and Alex A. Jones. She teaches at the School of Visual Arts in the BFA and MFA Fine Arts Departments, MFA Computer Arts, and MFA in Art Practice.