The Anthropocene demands new ways of perceiving, interpreting, and, of course, living in the world. In Terra Forma, a new work produced for the web, Andrew Yang enacts his concept of “possibility aesthetics,” an imperative to direct empirical knowledge toward new imaginaries. Yang’s study of the Sanriku coast of Japan, as it is being reformed after the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and subsequent meltdown of the Fukushima power plant, draws from geological and art histories, phenomenological experience and sociological observation, philosophical and artistic vision. In this project, as with his art practice at large, Yang inhabits extremes of visionary imagination and scholarly care, both demanded by the conditions of the present.

Yang’s previously published work in Art Journal spans this range. In the Fall–Winter 2017 issue of Art Journal, the reviews section ran his annotated bibliography, “Naturalcultural Wonders to Anthropocene Disasters: A Bibliography for Possibility Aesthetics,” which also appeared in digital format on Art Journal Open. In that contribution, Yang locates “possibility aesthetics” in the precedents of Donna Haraway, John Berger, and others who offer alternative concepts of the human and ways of counteracting a civilization in the throes of extractive capitalism. He announces the urgency of this undertaking:

If Earth is a collective lifescape, then the question is how we will contribute to its resilience or to its decay, and what kinds of imaginaries will function as mediums for either path. Alas, art can no longer presume the privilege of humanistic neutrality (as if it ever really could). Representations of the human and nonhuman across art, design, and literature are nothing less than forms of possibility aesthetics. These aesthetics, as models, implicitly take a position on the shape of a future in which cultural and planetary histories have now irrevocably woven into one another.

Rejecting hierarchies of sense, identity, knowledge, and experience, Yang’s project invites new forms of insight without forgetting history. The sublime, for instance, persists in conceptions of landscape and the Anthropocene, but is coequal with the nonhuman in the “collective lifescape” that Yang illuminates.

In Terra Forma, an experiment with the format of a double-blind peer-reviewed art contribution for Art Journal Open, Yang models possibility aesthetics through the history and futurity of a landscape formed by geological epochs, the long tradition of landscape painting, the ambitions of modernism, and twenty-first-century technologies. In this exploratory digital landscape of the artist’s creation, we encounter documents, reflections from his own visits to the Sanriku coast, outside research, news clips, and other materials reflecting Yang’s radical and necessary interdisciplinarity. How else can we grasp the world today? How else can we change our thinking in order to survive?

—Kirsten Swenson, Reviews Editor, Art Journal

Terra firma expresses the idealized association of the land with stability and solidity. In reality, landscapes are in constant flux. While tectonic and climatic shifts continually reshape the planet’s surface, human will and artifice have become geological forces in their own right, tirelessly sculpting the land and its boundaries. In this way, it may be more meaningful to speak of the conditions of terra forma, in which land is understood as a place, a space, and a fundamental material of the Earth’s own continuous reworking.

In the summer of 2017, I traveled to four different towns on the Sanriku coast of northeastern Japan, an area devastated by a massive earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011 called by various names: 3.11, the Great East Japan Earthquake, 2011 Earthquake and Tsunami. The earthquake was the most powerful ever recorded in Japan, and the fourth most powerful recorded on the planet; in most areas of the coast the tsunami’s height was unprecedented, as was the destruction it caused.

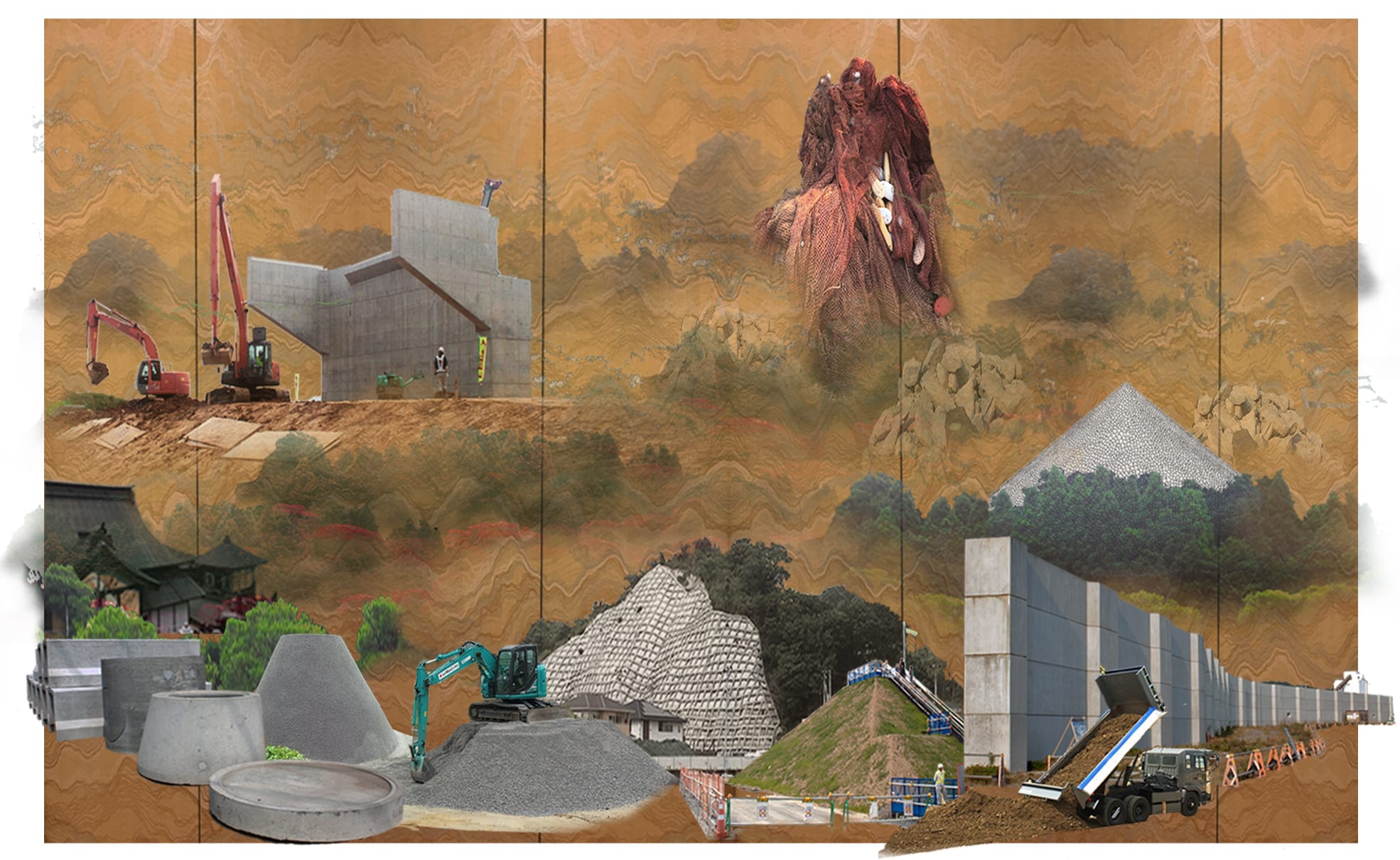

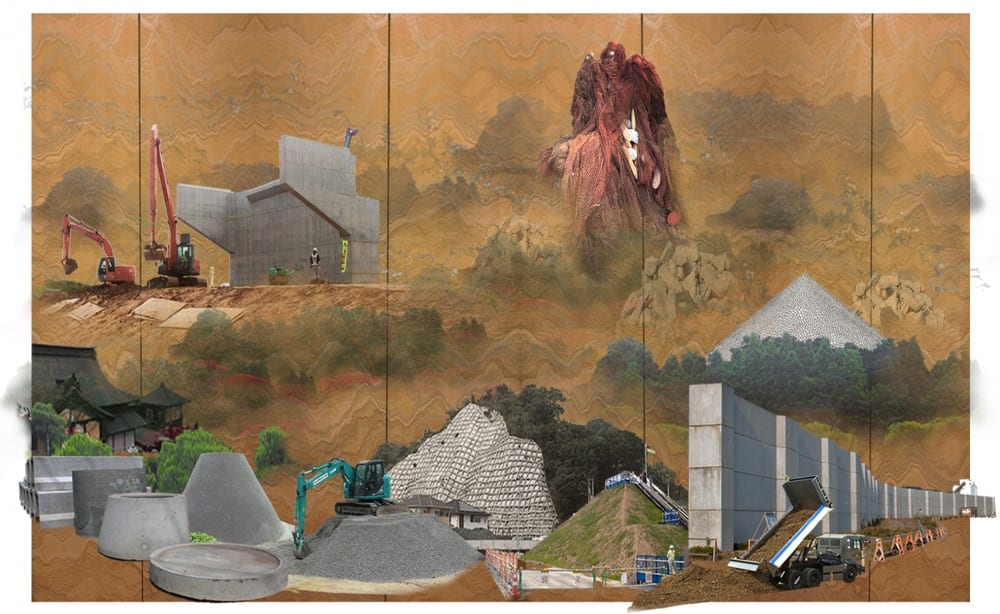

Seven years on, the coastline and its towns are still in the middle of an expansive recovery effort, including a wholesale refashioning of the coastline in hopes of mitigating future disasters. The various approaches that different towns are taking reflect local geographic conditions, but also divergent visions of resilience and nature-culture relations. In this way, the terraforming of the Sanriku coast might serve as a case study for “possibility aesthetics” within the Anthropocene.

From the Greek aisthanesthai (“to perceive by the senses or by the mind”), aesthetics is not primarily about a compelling sense of visual order, but moreso a sense of awareness, perception, and relation to one’s environment. What forms of awareness and what perceptions of nature, risk, and recovery does the terraforming of the Sanriku coast manifest? What future imaginary does it represent?

This project explores the aesthetics of the Sanriku coast by thinking of it as a garden—a space of culturally constructed nature as well as naturally constructed culture. The word “garden” derives from the Gothic gard, meaning “enclosure”; while in Japanese, garden (niwa, 庭 and teien, 庭園) is synonymous with “courtyard” as an outdoor enclosure. Such a spatial arrangement sets off what is culturally tended from the naturally untended, bracketing off intentional design from unintentional happenstance. The Sanriku coast is undergoing an otherworldly (and yet increasingly prevalent) landscape transformation, a kind of garden-making on a planetary scale that is a gesture of both analogy and identity, of the representational that becomes reality.

Andrew Yang is an artist and educator working across the naturalcultural. His projects have been exhibited from Oklahoma to Yokohama, including the 14th Istanbul Biennial (2015) and a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (2016). His writings appear in Leonardo, Biological Theory, Gastronomica, and Antennae, among others. He holds a PhD in biology and an MFA in visual arts, and is an associate professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.