This essay is part of the Afrotropes series, which began in the Fall-Winter issue of 2017 with the essay “Afrotropes: A User’s Guide” by Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson.

From Art Journal 78, no. 2 (Summer 2019)

what if in the beginning

the word was flesh

& the flesh became salt . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

even now/still the salt of a sea displaced

works its way into the corners of my eyes

—Deborah Jack, “a salting of sorts”1

Salt connects African diasporic subjects to the ocean across which their forebears were transported as slaves. In the works of Deborah Jack, and specifically those from the early years of the 2000s, the mineral variously manifests as rock salt, framing a portrait of the artist’s paternal grandmother in shadow boxes in her 2002 Foremothers series, and as five tons of salt layered on the gallery floor in the 2004 installation SHORE.2 Taken from her 2006 book of poetry skin, Deborah Jack’s “a salting of sorts” employs the phrasing of Genesis to install a body of salt in lieu of human flesh. The “salt of a sea displaced” acts as a mineral surrogate for the body, evoking the enfleshed presence of those enslaved and wrenched from Africa, then transformed into fungible property during the Middle Passage. In the subsequent line, Jack swiftly returns to the intimacy of the individual body in slavery’s violent history, as the salt—which is also the flesh—“works its way into the corners” of the narrator’s eyes, the solid residue of tears wept across time. The multivalence of salt in this poem crystallizes Jack’s use of salt as a material that draws the silenced traumas of African diasporic history into the present in the form of affect.

In concert with their conceptual weight in Jack’s practice, salt and the oceanic are deeply personal for this Caribbean artist. Born in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, Jack was raised in Sint Maarten, the Dutch half of the small leeward Caribbean island of Saint Martin, located approximately 230 miles (370 kilometers) east of Puerto Rico.3 Working in the media of photography, film, and installation, Jack uses her own diasporic and peripatetic position—splitting her time between New Jersey and Sint Maarten—to inform her aesthetic exploration of the Caribbean. The artist says that her practice “represents my multiple modes of existence/being and my constant shifting of the concept of home . . . [whereby] my body becomes a site for this flux and flow.”4 Jack conceptualizes a reciprocal relationship between the African diasporic (and specifically Caribbean) woman’s body and the geography of the island through salt.5 This relation provides one means of reaching into the murky histories of slavery and colonialism that color a Caribbean landscape marked by the residues of plantation agriculture and commercial tourism.

When Jack was asked in an interview to describe the “‘particular’ colonial position” of Saint Martin, her response hinged on salt and its history as a commodity produced on the island.6 Drawing from the mineral’s corrosive chemical properties, Jack deploys salt as an aesthetic material that promises to strip away the layers of tropical tourist imagery to “get to what’s underneath something,” and, as she says, “sometimes it is not always pretty.”7 Attending to the underbelly of tourist imagery, Jack’s artworks embrace the duality of what art historian Krista Thompson defines as “tropicalization.” This is a doubled visualization of the Caribbean in which representations of the tropics can function both for tourist consumption and in a subversive mobilization of tropical imagery as a form of resistance.8 Salt, as Jack conceptualizes it, can serve to both corrode and preserve the persistent trauma of colonial histories. “Salt can do either/or,” Jack states. “That’s where salt became a metaphor that I keep revisiting: to use it as a tool to play and excavate some of those ideas of history.”9

Centered on two works from the early 2000s, this essay argues that Jack uses salt—and its relation to the ocean—as a material form that solicits an afrotropic affect, reorienting the colonial mechanism of history toward slavery’s past as it persists across time in black bodies and the Caribbean landscape of the present. Already, my argument requires explication; the words afrotrope and even affect have little, complex, or contradictory meaning depending on their use. To begin, afrotrope is a neologism, defined by art historians Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson as “those visual forms that recur within and have become central to the formation of African diasporic culture and identity” in the modern era. Attending to these visual repetitions that articulate the multiplicity of African diasporic visual culture, “Afrotropes . . . offer a vital heuristic through which to understand not only how visual motifs take on flesh over time, but also to reckon with what remains unknown or cast out of the visual field.”10 Explicit in the proposition of the afrotrope is the ability of the visual-material form to recast, reorient, or otherwise re-member (both physically and psychically) the simultaneous mechanisms of historically suppressed violence and indefatigable persistence that structured—and continue to structure—black ontologies in the New World. I argue that the fluid spatiotemporal relationship between history and present proposed by the afrotrope readily lends itself to an affective thinking about the visual and material forms that recur in African diasporic artistic practices. Led by the salty provocations of Deborah Jack’s artworks, this essay seeks to present the afrotropic affect as a reorientation of affect theory away from a nebulous language of immanently present and pre-individual potential toward form and the material.

The so-called affective turn of the past two decades has profoundly marked humanities scholarship with its displacement of the individuated, self-contained subject in favor of the analytic weight held out by affect’s formless, nonstructured relation to the body itself. The theory has been primarily formulated in a lineage of Deleuzian, Spinoza-informed criticism that construes affect as an infinitely subtle, yet infinitely possible corporeal intensity that manifests its critical potential in “a body’s capacity to affect and be affected.”11 As media theorist Brian Massumi influentially defined the term, “affects” are bodily intensities that defy or resist reduction to cognitive perception and linguistic capture; affects are powerful in their unstructured autonomy—they are transindividual and transcorporal, constituted across bodies that fleetingly come into contact with one another.12 Common in much of affect theory, then, is an abstraction of the material body as a diffuse site of potential exterior to itself. Affect’s analytic strength lies in its illusive indefiniteness, its capacity to simultaneously be everywhere and nowhere, embedded in and beyond the material. Film theorist Eugenie Brinkema has pointedly criticized this thread of affect theory, and its application to film criticism, as a dissolution of the subject in affect’s nonsystematic and antistructural potentiality that paradoxically reinscribes a particular sort of subject in the spectator.13 In response, Brinkema proposes, “affectivizing form itself” as a methodology that “involves de-privileging models of expressivity and interiority in favor of treating affects as structures that work through formal means, as consisting in their formal dimensions (as line, light, color, rhythm, and so on) of passionate structures.”14 Within Brinkema’s theorization, affect retains its radical exteriority and mobility while also grounding these potentials in the form of the text itself—and the object by extension.

My examination of salt as an afrotropic affect in Deborah Jack’s artwork seeks to further nuance Brinkema’s challenge to and restructuring of affect theory by attending to the particular ontological conditions of blackness that structured and were structured by chattel slavery in the Atlantic World. The conjuncture of form and affect in Brinkema’s articulation provides an alternative approach to contending with the affective historicity that emerges between bodies (figured and unfigured) and the materiality of salt in Deborah Jack’s artwork. Literary scholar Hershini Bhana Young’s writing on Deborah Jack provides a foundation for reading the materiality of salt in Jack’s work affectively. Young argues that salt, and its inextricable relationship to the ocean, “constitutes a unique form of memory that is at once both alive and not.”15 Drawing out this relationship between memory and history, life and death, I argue that Jack mobilizes salt as an afrotropic affect that remembers and recounts its own histories of slavery through the sensorial experience of form.

As such, my own development of afrotropic affect is informed by black-feminist theorizations of the black body’s fungible materiality. In her reading of “the elusiveness of black suffering” in the antebellum United States, literary theorist Saidiya Hartman highlighted “the qualities of affect distinctive to the slave economy” in which “the fungibility of the commodity makes the captive body an abstract and empty vessel vulnerable to the projection of others’ feelings, ideas, desires, and values.”16 In other words, the enslaved black body becomes an affective form through which the white master and abolitionist could feel the extent of domination, an oppressive power relation embedded in the afrotrope and representations of blackness. Crucially, the fungible black body is not simply relegated to the annals of history; rather, this affective form perniciously works its way transhistorically in the form of black flesh. Literary critic Hortense Spillers importantly separates the black body from the “flesh,” which she defines as an a priori materiality “that does not escape concealment under the brush of discourse, or the reflexes of iconology.”17 The violence of slavery is never shed from the black flesh it was perpetrated against but marks the body with “a kind of hieroglyphics of the flesh” that “actually ‘transfers’ from one generation to the next.”18

Drawing from Brinkema, Hartman, and Spillers, I argue for the trans-historicity of salt as an afrotropic affect in Deborah Jack’s photographic, filmic, and installation pieces. Salt is not simply a surrogate for or an extension of the black body in Jack’s practice; rather, the mineral itself takes on flesh as an afrotropic affect, manifest in material form, that reconfigures blackness as exterior to any individual body marked by its sign. This essay presents a particularization of affect’s politics, when blackness is placed at the center, toward the material afrotropic forms that figure the ineffable weight of slavery’s concrete past in relation to the bodies marked by that history in the present.

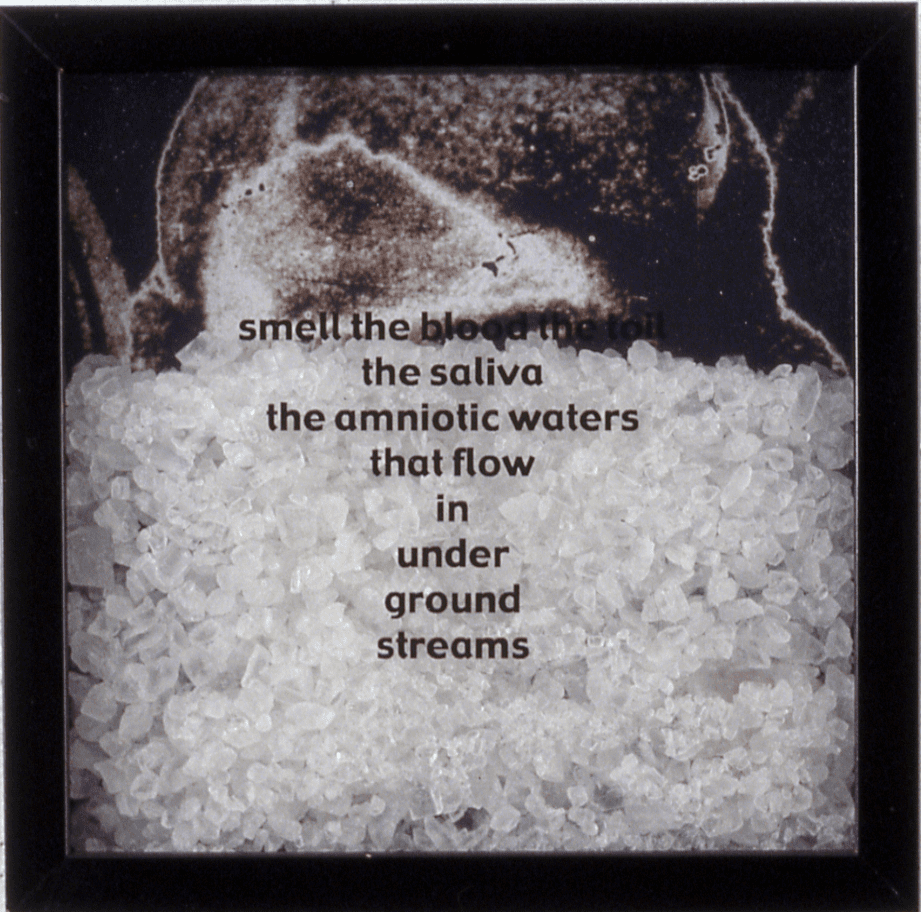

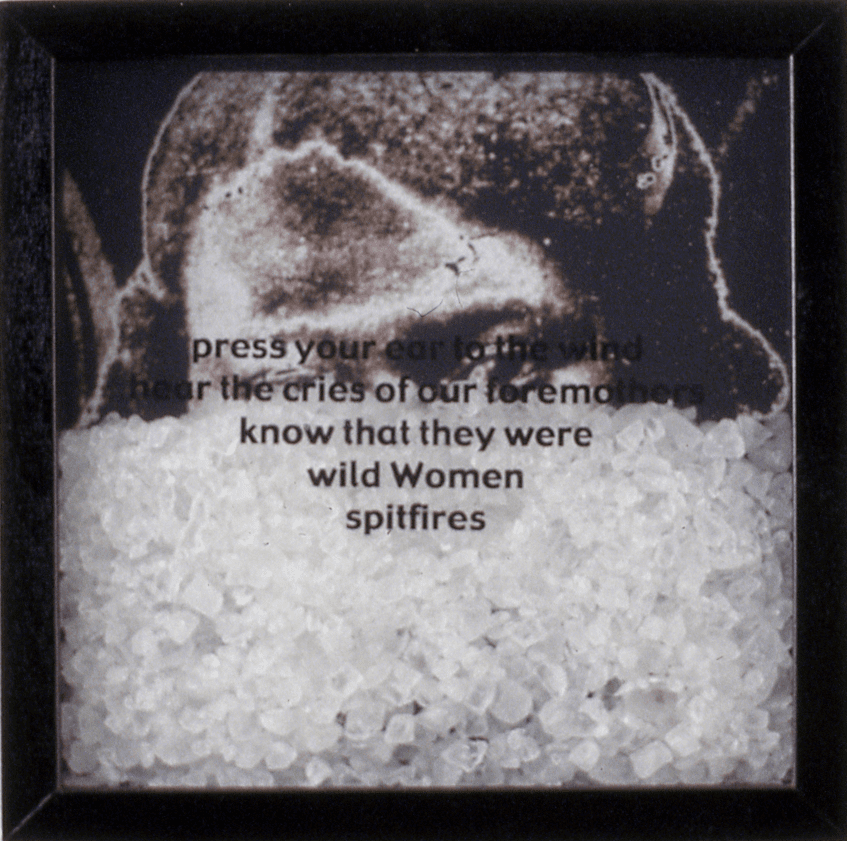

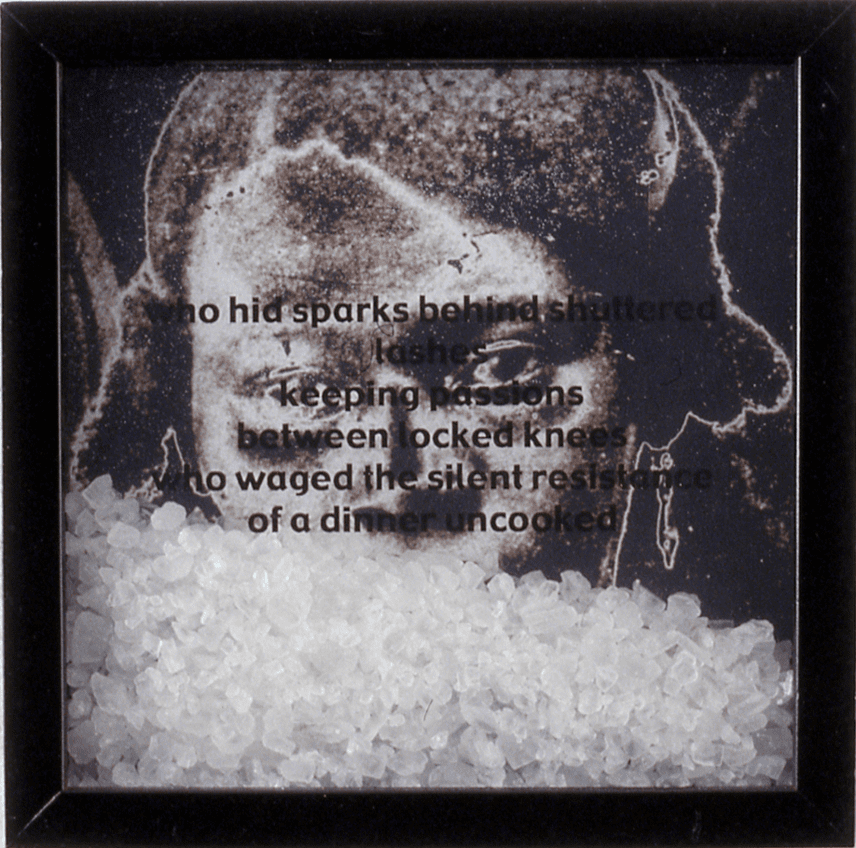

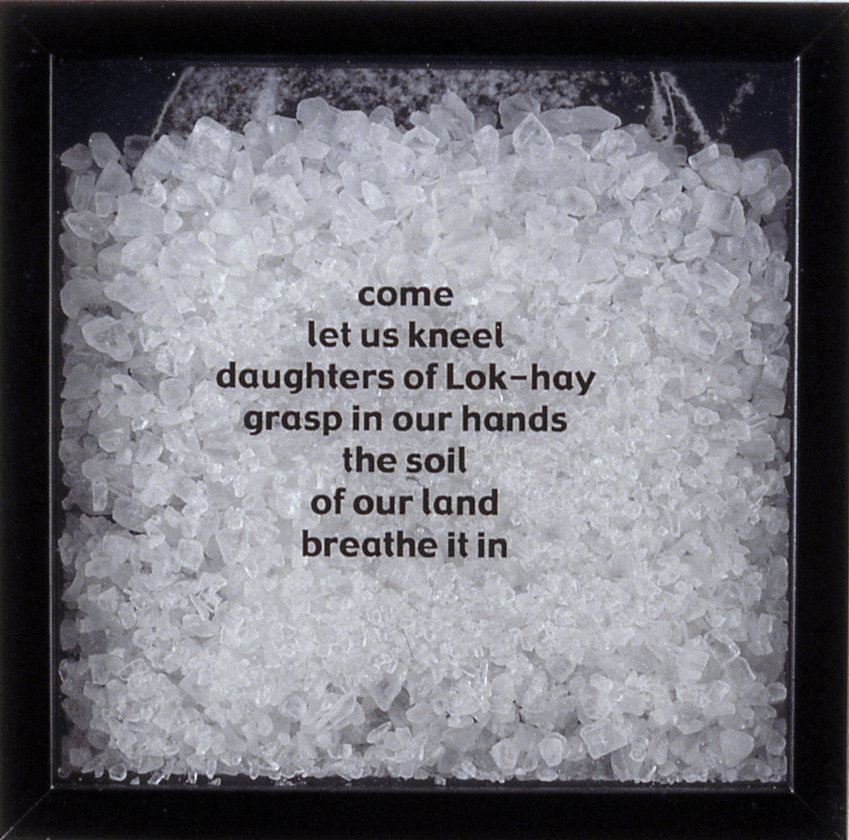

Deborah Jack, Foremothers, 2002, salt, digital print, wood, glass, 10 x 10 x 1 in. (25.4 x 25.4 x 2.5 cm). Collection Adriane Little (artwork © Deborah Jack; photographs provided by the artist)

Affective Histories Laden with Salt

Across five shadow boxes, the visage of a youthful black woman slowly comes into view from behind a veil of crystalline rock salt. It is only in the third shadow box that a discernible figure emerges. The piercing gaze of a single eye confronts the viewer, while the other eye is obscured behind bleached salt that shimmers iridescently from within the shadow box. From the scant visual evidence provided in this tightly cropped and digitized sepia-toned portrait, one can discern the texture of the figure’s hair, plaited close to her scalp. Her hair plays against the ridge of her brow, which catches the light and accentuates the undulating surface of her face, cast in alternating reflections and deep shadows. The formal relationship between the uneven layer of salt that disappears and the reproduced photograph of the artist’s paternal grandmother that appears in this series posits a metaphorical rapport between the black woman’s representation and the salt that conceals her. In Jack’s 2002 Foremothers series, salt functions as a predicate that adheres to the figure of the black woman in the frame, providing a palpable yet indeterminate context for her image. Salt, because of its history in the Dutch Caribbean, becomes one means of reformulating black women’s history in Sint Maarten through the afrotropic affect’s material presence.

Salt is an affective form that draws together the specific geography of Saint Martin and the black woman’s body in order to conjure the suppressed and unrecorded histories of slavery with the mineral central to Sint Maarten’s colonial economy. Salt and its production are inseparable from the colonial history of Saint Martin, dubbed “Salouiaga,” or “land of salt,” by the indigenous Caribs. Settled by the Dutch in 1631, after the French and English had already staked claims to other islands in the Lesser Antilles, Sint Maarten was the first Dutch colony in the Caribbean and served a strategic economic role as a convenient port between the older colony of New Amsterdam and the newer holdings in Brazil, a small portion of which was controlled by the Dutch East India Company between 1624 and 1654. Unlike many other Caribbean islands caught in the colonial land grab, with the notable exception of Hispaniola, Saint Martin carries with it a history of bifurcation. In all likelihood unbeknownst to early Dutch explorers, the French had established their own settlement two years prior to the arrival of the Dutch.19 After being ousted by the Spanish in 1633, only two years after the initial settlement, the Dutch expanded their colonial claims to the Caribbean with the acquisition of Curaçao in 1634 and Saint Eustatius in 1636. The French and Dutch regained control of Saint Martin in 1648 and solidified its division between the French north and the Dutch south with the Treaty of Concordia, which is still in effect today.

Although plantations proliferated across the Dutch half of the island, imperial entrepreneurs quickly discovered that the island was too arid to sustain any profitable large-scale production of the water-intensive cash crops synonymous with the Caribbean plantation system. The Dutch retained their claim on Saint Martin largely because of the abundance of salt on the island, an indispensible commodity for the Dutch herring industry and international shipping ventures.20 The island’s geography, in particular the proximity of the Great Salt Pond to the Great Bay on the southern tip of the island, naturally led to salt production. Salt exportation from Sint Maarten grew rapidly from the late eighteenth century through the mid-nineteenth century, increasing from 600,000 bushels by 1795 to a peak of 900,000 bushels annually by 1834. These were remarkable sums given that industrial salt production in the later twentieth century barely surpassed these numbers.21 Jack’s emphasis on salt affectively traces the history of slavery in Sint Maarten—and the Caribbean generally—but she also deploys the mineral to reckon with the gradual decline of the economy following the emancipation of the enslaved.

In a recent reevaluation of the “apparent dullness” of colonial history in the Dutch Caribbean, historian Gert Oostindie attempts to retrace the overwhelming ambivalence of the Dutch toward the belated abolition of slavery in 1863.22 Despite his interest in unsettling the conventional narrative of Dutch Caribbean history as a nonevent, Oostindie draws hard and fast distinctions between the cruel overextension of slave labor in the continental Americas and the “milder labor regime for the slaves” on the islands.23 For Oostindie, Dutch emancipation was fundamentally a matter of imperial respectability as abolition spread throughout the Atlantic World—with Haitian independence in 1804, abolition in the British Empire in 1834, and in the French and Danish empires in 1848.24 By characterizing slave life on the Dutch isles as “physically less merciless” and highlighting the lack of vehement political debate surrounding emancipation, Oostindie does not account for the active revolts in Dutch Suriname in 1763 and 1772 and the defection of slaves to the French side of Saint Martin after 1848.25

In an early interview, Jack posited a connection between the representations of her grandmother in these reproduced photographs and the Great Salt Pond as a means of redressing such omissions from colonial history. Although it was once a center for the salt industry, the large pond is now polluted, after production was halted in the mid-twentieth century. “The Great Salt Pond,” Jack explained, “is a geographic symbol that recurs often in my work. In ‘Foremothers,’ for example, I work with photographic images of my paternal grandmother. . . . Note the use of salt in my work.”26 With her aside, “for example,” the artist’s own cognitive leap, from the physical space of a saltwater pond to the relationship between salt and the body, is telling. Salt functions as a multivalent afrotropic affect; it is a material form around which the physical space of the now-polluted salt pond and the liberatory potential of black women’s histories are held in tension with colonization’s subjugation of the flesh.

The conjunction of the “afrotrope” with “affect” in Foremothers, I argue, complicates Brinkema’s assertion that affect “is non-intentional, indifferent, and resists the given-over attribute of a teleological spectatorship with acquirable gains.”27 The specificity of salt as an afrotropic affect in this piece does not materialize as indifference or a full negation of intention. Nor does it reinscribe the exteriority of affective form to the telos of a particularized spectatorial subject. Rather, salt and its relationship to the black woman’s body instantiate affect as a form to contend with the ineffable historicity of black subjectivity as it was denied to African diasporic individuals in the Caribbean.

Salt as an afrotropic affective form connected to women’s embodied presence on Saint Martin materially contends with the transhistorical struggle for black being. Jack intimated the centrality of her grandmother to her aesthetic “rememory,” evoking Toni Morrison’s term for the act of “remembering a memory,” as a mode of representing the unrecorded histories of slavery and its legacy on her home island. Jack said that she deployed her grandmother “as an iconic figure to form a personal/family history that is lost.”28 Describing the topography of Sint Maarten, with its central Great Salt Pond, the artist posits an intimate connection between the landscape as a vessel that holds these lost or subjugated memories and the unique historical and ontological position of the African diasporic woman before, outside, and interpenetrating white (post)colonial patriarchal culture.29 Salt, then, is used as a deeply personal affective form in Foremothers. Yet, Jack’s aesthetic use of this crystalline commodity also unfurls that affective historicity outside of the discursive colonial record. Salt becomes a conduit that brings the history of slavery into the present through the affective weight of the land itself. The salt that both threatens to smother and promises to protect the image of this matriarch Jack “never knew” covers over and simultaneously gestures toward the preserving and eroding properties of the mineral Saint Martin was colonized to produce.30

Jack underlines the erasure of history and tradition that continues to be felt on Saint Martin today and its centrality for her own artistic production: “My counter to this absence is to create these mythologies/this mythology that has been lost.”31 In Foremothers, Jack proposes mythology as a counter to history through the affective form of salt as it rests between the layering of text upon the buried image of her grandmother. In the first framed box, there is only a scant indication of the figure beneath; salt dominates the frame. In its stead, the sans serif text printed on the glass introduces the viewer to the slave mythology of Saint Martin, as Jack calls together the “daughters of Lok-hay” to “grasp in our hands / the soil / of our land / breathe it in.” Lohkay is remembered and memorialized in Sint Maarten as a valiant Maroon (fugitive slave) who was captured after her first escape and punished by the planter with the brutal removal of one breast.32 After being nursed back to health, One-Tété Lohkay, as she came to be called, escaped again to live in freedom in the hills. Rather than represent Lohkay as the embodiment of women’s rebellion on the island, Jack conjures her presence affectively in relationship to the salt that grounds her textual evocation and her connection to the image of the grandmother who lies in waiting beneath a veil of salt. Foremothers confounds myth and history through the contradictory affects of colonial violence and enslaved rebellion that salt formally evokes in the act of encounter.

Foremothers further emphasizes the ability of salt—as an affective form central to slavery and freedom on Saint Martin—to weave myth and history with the lines of overlaid text in the third shadow box that further obscure visual access to the image. Through visual text the provocative exclamation commands the viewer to listen: “press your ear to the wind / hear the cries of our foremothers / know that they were / wild Women / spitfires.” The cries of these foremothers, who rest in the realm of Jack’s own “rememory,” extend the weight of salt as an afrotropic affect across the diaspora and across the temporal distance that differentiates enslaved from free. This is a community of “wild Women spitfires” scattered to the four winds but connected and preserved by salt.

Offering many parallels to the memory of Lohkay in Jack’s work, The History of Mary Prince—a slave narrative first published in 1831—is an analogous text from the British Caribbean that bridges past and present in the afrotropic affect of salt. Mary Prince’s narrative brings the wounds against diasporic flesh into the discursive structures of hegemonic history. In 1806, Prince—who had been born into slavery on the island of Bermuda—was sold to work in the salt flats of Grand Turk Island, where she was forced to stand in the highly salinated water for hours at a time, harvesting the mineral crystals for export. Prince positions the wounds perpetrated against her commodified, peripatetic flesh as affective material inextricably bound up with the accumulation of salt: “Our feet and legs, from standing in the salt water for so many hours, soon became full of dreadful boils, which eat down in some cases to the bone.”33 Devoured by the colonized, tropical landscape, Prince bears her laborious journey—as is archetypal of so many unrecorded histories—upon her body through the scars of wounds repeatedly healed and reopened.

Moreover, Mary Prince’s narrative provides a foundation for the use of salt as an affective form to ground the sonic rebellion of Jack’s foremothers, those “wild Women spitfires” whose cries reverberate within Caribbean history. Early in the narrative, Prince recounts being sold as a young girl. The separation from her mother and siblings profoundly affected her, constituting an originary site of trauma. “Oh the trials! the trials!” cried Prince to her abolitionist scribe in 1831. “They make the salt water come to my eyes . . . when I mourned and grieved with a young heart for those whom I loved.”34 This exclamation is nearly extradiegetic; it is an affective wail that disrupts the temporal continuity of the narrative and reverberates throughout the text. Deborah Jack extends Prince’s metaphorical equation of her salty tears with the salt water of the ocean in her poem “a salting of sorts”: “even now / still the salt of a sea displaced / works its way into the corners of my eyes.”35 Jack’s own connection between the sea and the unnamed tear solidifies the salt of Prince’s lachrymose exclamation as an afrotropic affect that holds the potential to mourn slavery’s historical violence in the present. These tears can be considered through the prism of Brinkema’s own analysis of the tear that severs its direct linkage to the manifestation of the emotional, “the posterior expression of some anterior cause.” Rather, as an affective form the tear “is no longer a privileged sign of emotionality, but an energetic corporeal state rather like running or striking an opponent, trembling skin or quivering viscera.”36 Yet, in the context of the afrotrope, affect complicates any temporal relationship to this “energetic corporeal state.” In Jack’s work, salt provides the affective material necessary to confound the myth and history of black Caribbean women. Salt as an afrotrope forms one foundation upon which the cries of the foremothers against slavery and its afterlives can be affectively felt—rather than only heard.

Drawing out the deferred sonic aspects of Jack’s piece highlights what Fred Moten calls “the generative force of a venerable phonic propulsion” that enacts “the freedom drive that animates black performances.”37 Particularly relevant for Foremothers, Moten places black women’s vocality at the center of his analysis of “the echo of Aunt Hester’s scream,” from Frederick Douglass’s 1845 Narrative of the Life, “as it bears, at the moment of articulation, a sexual overtone, an invagination constantly reconstituting the whole of the voice, the whole of the story.”38 While Moten mobilizes the music of blackness primarily in relationship to Karl Marx’s “commodity who speaks,” his analysis bears equally well in the affective register. The black woman’s voice—emblematized by the concomitant textual residues of Aunt Hester’s scream, Mary Prince’s wail, and Foremothers’s call to hear—presents an affective form directed toward the transhistorical trauma of slavery in its “radical exterior aurality.”39 The synesthetic mixing of the sonic and the visual in Jack’s shadow boxes offers up to the viewer the potential to feel the sonic residue of Afro-Caribbean women’s resistance cries that are muffled not only under a layer of salt but also in the silence of the photograph itself.40

In Foremothers, salt emerges as an afrotropic affect that holds the potential to disrupt and reconfigure colonial histories of Sint Maarten through its relationship to Jack’s imagined and mythic community of foremothers. The mineral so integrally related to the history of her home island materializes the act of “sucking salt,” a Caribbean women’s saying that connotes a preparation for hardship.41 Salt embraces the contradictions of remembering an African diasporic past that was violently suppressed through slavery and the mechanisms of colonialism. Salt’s ability to both corrode and preserve functions affectively in Foremothers, instantiating a fluid relationship between black women’s freedom struggles in the past and their resonance in the present. Jack’s subsequent installation SHORE draws salt together with the oceanic in a concatenated exploration of blackness and the potential to tell its histories by affective means.

The Interwoven Affects of Salt and Sea

Salt as an afrotropic affective form, explored in Foremothers, is monumentalized with its relation to the oceanic in Deborah Jack’s 2004 installation SHORE, held at the Big Orbit Gallery in Buffalo, New York. In Jack’s hands, salt expands the boundaries of understanding black women’s labor in the Caribbean across time through affect. In Foremothers, Jack takes up the dual ability of salt to preserve and decay. Her photographic series emphasizes the potentiality to remember and re-member the enslaved who were expunged from, or otherwise elided in, colonial history. In SHORE, Jack expands the afrotropic potential of salt into that of the oceanic with an affective network of feeling that conjures a body without figuring it.

A wave of sensory stimuli crashes over the spectator walking into the darkened gallery. Three billowing nylon screens—slack rather than taut, to metonymically signal a ship’s sails—are arranged throughout the gallery to form the visual foundation of SHORE. Rich, amber-toned Caribbean seascapes, of a motorboat’s wake and an inverted vignette of waves lapping at a rocky shore, and satellite footage of a hurricane shaded a deep ultramarine blue are intermittently projected on the three screens. These scenes are juxtaposed against the abrupt cut to a vertiginous panning, close-up shot of a colonial-era ship’s mast. Speakers placed throughout the gallery emit the hushed roar of the ocean, rhythmically punctuated by the creaking of wood, which floods the spectator’s ears. Five tons of brown and pristine white rock salt, harvested from western New York and imported from the Bahamas, respectively, are dispersed in layers across the gallery floor. The crunch of salt sonically and tactilely implicates the viewer in the installation. The perception of the tropical and its violent history are fundamentally denatured, ruptured, and reframed as these images of an earth-toned, oceanic infinitude are reflected in a twenty-by-forty-foot reflecting pool situated in one corner of the gallery. The pool itself takes on afrotropic resonances in its spatial relationship to the salt that covers the gallery floor. The pool and the salt emerge as material metonyms for the Atlantic and the enslaved bodies forced to cross it. The placid surface becomes another screen through which to contend affectively with the histories of colonialism and slavery in the tropicalized Caribbean.

In her catalogue essay for the SHORE exhibition, curator Sandra Firmin emphasizes the transitional and durational aspects of Jack’s installation. The work, she argues, “captivates viewers immediately with its exploration of arrival and departure, and the passage in between. . . . This transition from solid white [salt] crystals to liquid black, coupled with the mirroring of two large-scale projections across the far wall and onto the water, produces the sensation of a precipice.” Retaining the “discrete textures and complex reference systems” of what the curator perceives as disunified material addenda to the three-channel videos, “Jack’s works converge to create a sensory environment that compels viewers to sit and listen.”42 And yet, importantly, Firmin does not assert that what the viewer hears will be understood in a traditional sense. Rather, she argues that the “material symbolism and representation” central to Jack’s practice is often “inscrutable” in its signification.43 Drawing out the simultaneous sensory richness and inscrutability of SHORE as a composite assemblage of referential and symbolic units, Firmin’s essay proffers sustained engagement as one useful method through which to engage the nuanced aesthetics of Jack’s installation.

Expanding upon Firmin’s analysis, I suggest that dwelling in SHORE’s interstice between sense and understanding draws out the afrotropic affect as a cohering force in material form. An affective engagement with this installation threads together the history of slavery and its supposed erasure from the contemporary, tropicalized Caribbean landscape. SHORE conjures the intimate affective connection between salt, the oceanic, and merciless slave labor in an attempt to rupture the false ahistoricity of the tropics as a site bound to its supposedly timeless, unchanging beauty.

Jack’s attention to the sonic, haptic, and olfactory qualities of salt and the oceanic further heightens the synesthetic unity of the piece. The ocean and the crunch and smell of salt are woven into and become inextricable from the visual in SHORE. In their totality, these visual inversions, sonic interruptions, and haptic disjunctions defy any clear resolution. Rather, these assembled sensorial provocations cohere in the affects that emerge between, across, within, and in relation to their discreteness. Layers of brown and pure white salt blend together in material waves as spectators perambulate through the gallery. Literary scholar Hershini Bhana Young also emphasizes the blending of salt on the gallery floor. She asserts: “The mixing of brown and white salt reminds us of the complex processes of cultural negotiation where the fates of Africans and their captors became inextricably entwined, simultaneous, layered.”44 The abundance of salt, in Young’s analysis, “provides Jack with a substrate for emotional memory—what ‘the nerves and skin’ remember. It evokes the ghosts of the ancestors . . . insisting that the past is not over.”45 Drawing Young’s argument into the terms of the afrotropic affect, SHORE ruptures the relation between past and present through the affective forms of salt and the oceanic, signaling not only the entwined relationship between colonizer and colonized but also the affective pasts that structure black being in both Africa and its diaspora.

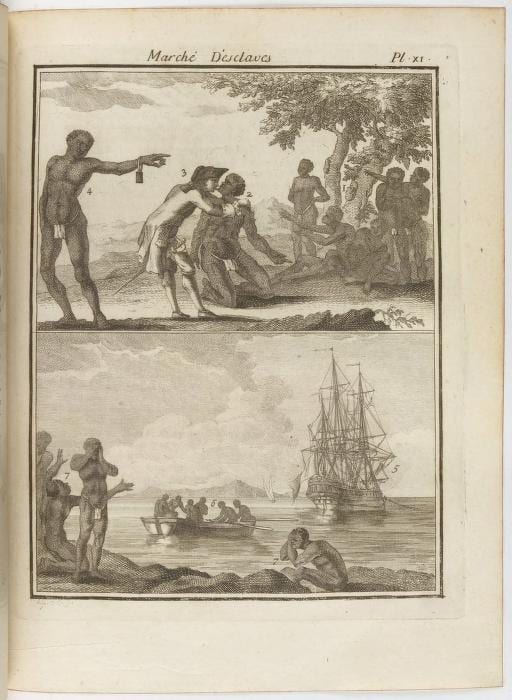

As I speculatively extend my analysis to the wider political and cultural economies of salt in the New World, an eighteenth-century engraving and the nineteenth-century records of an American abolitionist offer useful insight into Jack’s connection between salt, the oceanic, and the enslaved body. Published in 1764, Le commerce de l’Amérique par Marseille—a two-volume study of royal patents that regulated the commerce between the French port of Marseille and the Antilles—contains a plate that portrays a perplexing aspect of the slave trade.

The bottom half of the image depicts a group of Africans grieving the loss of loved ones abducted and enslaved. In the top half of the image, a European slaver leans over an African who is posed on bended knee, nude except for a loincloth. The slaver sticks out his tongue to lick the sweat off the enslaved man’s chin. Chambon, the French author, takes a moralizing position to describe this practice, purportedly executed only by other European slave dealers: “They are not ashamed to bend down in order to lick the skin [of the enslaved] to discover by the taste of the sweat if they had not contracted certain illnesses.”46 These slavers were tasting for salt in the sweat of enslaved Africans as an indicator of health. As such, Deborah Jack’s insistence on salt as an afrotropic affective form in SHORE enfolds the entirety of the Middle Passage into her installation by way of salt’s intimate relation to the black body itself.

Salt also played a central role in the lives of the enslaved in the New World, as recounted in a collection of abolitionist testimonies published nearly a century after Le commerce de l’Amérique by the American abolitionist Theodore Weld. In his text, Weld described the common practices of bathing the wounds of whipped slaves “with a brine of salt and water” or rubbing a sadistic mixture of red pepper and salt directly into the wounds as an excruciatingly painful means of sterilization.47 In addition, he enumerated the typical allowance of one pint of salt a month, if it was provided at all. Citing another abolitionist, Weld recounts: “In some cases the master allowed no salt, but the slaves boiled sea water for salt in their little pots.”48 In conjunction with the application of salt to the enslaved body, this modest performance of subsistence salt production stands in contrast to the use of brine to further torture whipped slaves. The complexity of SHORE rests in the affects that emerge between these two poles. The salt that covers the gallery floor acts as an affective form that holds out a liberatory relationship to Saint Martin’s colonial past—and the history of the diaspora generally—just as that liberatory re-memory recedes into the discursive historical record of violence and enslavement.

With the knowledge of salt’s centrality to Sint Maarten’s history, this expansive material field can be seen as an unsteady ground upon which Jack’s video and sonic additions are founded. The doubled rippling wake of a motorboat lingers on the screen and quadruples as it is reflected in the pool before it. The disparate creak of a slave barque manifests sonically before its visual form is seen. Footage of eroded tree bark interrupts other segments and briefly twins itself on the central screen. Together these vignettes present a cacophonous enunciation of Sint Maarten’s historical paucity. They propose a polyvocal set of memories materialized in the affective forms of salt and the oceanic. These are fleeting histories, myths, and re-memberings that flourish in the “energetic corporeal state” of affects engendered by the unsure footing on a pile of salt and in the ocean’s sensuous whispers that fall on strained ears. Jack aesthetically brings to bear the open sores of slave labor in the salt flats in order to disrupt them and to throw these unrecorded traumas into the future perfect, an irresolvable “will have been” of diasporic being that impresses its history and futurity onto the black laboring body that is hauntingly present despite its figural absence in the piece.

In her analysis of the installation, Hershini Bhana Young draws upon a language of ghosts and haunting to emphasize the ways in which Jack presents history as a sort of palimpsest.49 For Young, the past and present come together in the phantasmal residue of the diasporic body retained in the present by way of Jack’s deliberate aesthetic of layering throughout.50 Young poetically calls forth the emotional waves of history that draw the ghosted presence of the diasporic body near to the physical presence of the spectator. “We are part and parcel of the emotional palimpsestic installation that Jack creates,” she argues “in order to convince us that the past is not yet over, but still vibrating, creaking eerily in the present like a ghost ship, demanding that we remember.”51 Young provides a crucial foundation for my own reading of SHORE with her evocation of a vibrating past that uses Brian Massumi’s language of affect to understand Jack’s relationship to history. My proposition of salt and the oceanic as interwoven afrotropic affective forms seeks to further nuance and extend Young’s argument by also drawing out Jack’s amalgamation of past and present to critique not only colonial history but also the neocolonial present in Sint Maarten. Throughout the spectator’s multisensory engagement with the physical, sonic, and filmic manifestations of salt, Jack projects these histories upon the skin in the fluid grammar of sensory intensity—the salty and laborious sweat, tears, and blood of the afrotropic affective form.52

In SHORE, Jack continues her investigation of the scant, and often unreliable, evidence of the African diasporic visual archive to sever her work from the picturesque image of crystal-clear blue Caribbean waters.53 Her work carefully deploys the affective afrotropes of salt and the oceanic as a potential mode of contending with the violence of postcolonial being, but it remains undecided whether the ineffable scars of a tropicalized history elided by the tourism industry can, or should, ever be fully felt in the present. For a brief moment, video sequences of a hurricane and the inverted vignette of waves lapping at the shore flash onto the central screen. Twinning these scenes on the delicate, almost imperceptibly undulating surface of the reflecting pool, the corporeal cohesion of the spectating body is thrown into the hurricane’s swirling eye alongside the bifurcated visual perception.

Theorizing the longue durée of diasporic experience, Édouard Glissant departs from the colonized landscape of the island and positions the salty depths of the Atlantic as the originary site of a black oceanic ontology. Saluting the “old ocean,” Glissant expounds, “you still preserve on your crests the silent boat of our births, your chasms are our own unconscious, furrowed with fugitive memories.”54 The birth of the black oceanic in the abyss of the unknown produces, for Glissant, a knowledge that is “not just a specific knowledge . . . of one particular people . . . but knowledge of the whole, greater from having been at the abyss and freeing knowledge of Relation within the Whole.”55 With his emphasis on knowledge that emerges in relation, Glissant departs from the impossible coherence of an African diasporic past within history as a record of power to which the enslaved and their descendants had little recourse. The language of “fugitive memories,” and the possibility to know outside of a circumscribed wholeness, gestures toward an affective relationship between history and black existence in the present explored in Jack’s SHORE. Jack’s looping, interrupted, repeated, and disjointed video sequences are evocations of the shore without a determined arrival.

The affective forms of salt and the oceanic in SHORE structure a knowledge of African diasporic history in the Caribbean that contends with the violence and bodily trauma suppressed in the archives of colonialism throughout the diaspora.56 Here, I pointedly expand upon Brinkema’s “reading for formal affectivity” to attend to the afrotropic affect’s attention to the “form’s waning and absence,” which propounds a fluid relationship between past and present and eschews conformity with colonial history through the multiplied absence of a represented body in SHORE. On the one hand, the installation presents an illusion of affective satisfaction that conforms to the picturesque tradition in the Caribbean by tinting a tempestuous hurricane the rich ultramarine blue that is denied to Jack’s seascapes; SHORE quenches a thirst for the tropical beach only to leave the viewer thirsting for more. On the other, the optical and tactile uncertainty of the installation—with its floor of salt and shifting video—uses these affective forms to turn toward the interminable terror of the violence wrought by colonialism on the land and the ocean itself, a synecdochic referent for the collective body of the Caribbean. Submerging the viewer in this gap that intensely vibrates between perception and affective feeling, the work implicates the viewer’s own negotiation of this tropicalized space, highlighting the potential afrotropic affects of SHORE and using its aesthetics to extend far beyond the delimited space of the gallery.

Conclusion: To Feel Affective Form, or Feel Not at All

To experience salt and the oceanic in Jack’s work is to dive into the traumatic depths of African diasporic memory that dwell within and beyond the suppressed, subaqueous histories of slavery in the affective forms deployed in Foremothers and SHORE. These works are emblematic of the temporal fleshiness of the afrotrope and its ability to come into view or remain out of sight at various moments in time. Yet, these affective forms are necessarily ambivalent: salt, as a colonial commodity, and the oceanic, as an ur-site of black ontological dehiscence, can be mobilized in the service of both colonial histories and the liberatory potential of the affective form. The multiple registers of salt as an afrotropic affect in Jack’s work do not fully conform to Brinkema’s assertion of affect’s “indifference” in the service of an “energetic corporeal state” formalized as exteriority.57 Rather, the formalization of affect in Foremothers and SHORE is in pointed, afrotropic materials that conjure the nonlinear, suppressed historical conditions of slavery without ever attempting to conflate past and present. For the viewer approaching Jack’s works attuned to her process of stripping away hegemonic history through the afrotropes of salt and the waters from which it is culled, Jack allows the possibility of dwelling in the tension between the perception of conscious history and the affective sense of subjugated memory as it is felt upon the body. In so doing, the artist takes up and extends the art historical discourse in which the black body becomes, as art historian Huey Copeland asserts, a site of contestation always freighted with the operations of resistance and oppression.58 An attentive reading to the nuanced flows of water and salt as they relate to both the spectatorial and spectral diasporic body within Foremothers and SHORE extends Copeland’s demonstration that the black body’s “absences, presences, and surrogates signify within and in relation to the sites which have been so crucial to its figuring.”59 Jack’s salt works highlight the slippery distinctions between the body as an affective potential and the geographic places that generate and structure those affective bodies. Ultimately, the afrotropic affect is most powerfully brought to bear on the relationship between spectatorial embodiment and the absent diasporic body in Jack’s work as a formal potential. As viewers interacting with her photographic and installation work, we inevitably bring with us the weight of our own infinitely varied affective histories. This is the blending of colonial and colonized perspectives that Young so eloquently draws out in her analysis of the brown and white salt in SHORE. The afrotropic affect may be only an ephemeral, momentary glimpse into the innumerable pasts of black women in the diaspora that vibrate between the past and present, the conscious and unconscious. However, it is in the affective form of these moments that Jack kindles the potential for an alternative, relational knowledge of slavery’s history through the materiality of salt. It may be akin to the terrifyingly revelatory plunge into the water, or it may not be felt at all.

C. C. McKee is a dual-PhD candidate in the department of art history at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris and will soon begin as assistant professor of modern art in the department of History of Art at Bryn Mawr College. McKee’s research includes contemporary African diasporic art, colonial Caribbean visual culture, and the art history of science in the Atlantic World. McKee also maintains a curatorial practice informed by queer and critical race perspectives.

- An expression of gratitude to Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson, who offered their invaluable thoughts and guidance from the initial conception of this research. Thank you to Hannah Feldman, whose incisive comments enriched this essay in innumerable ways. The author is grateful for the attentive engagement and productive critiques of Douglas Gabriel, Rachel Levy, Emily Wood, and the anonymous reviewer for Art Journal. Finally, my sincere thanks are due to Deborah Jack, who encouraged this project early on and generously granted permission to reproduce images of her work.

The epigraph is from Drisana Deborah Jack, skin (Philipsburg, Saint Martin: House of Nehesi, 2006), 27. ↩

- Beyond the scope of this essay, salt is also a central motif in Jack’s 2006 work bounty, a series of illuminated slides that depict mountainous piles distilled from salt flats. ↩

- Throughout this essay I will use the Dutch spelling, “Sint Maarten,” when specifically discussing the Dutch half of the island and the English spelling, “Saint Martin,” when referring to the entire island. ↩

- Deborah Jack, Artist’s Statement, 2004, https://www.headmadefactory.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/statement_deborah_jack.pdf. ↩

- Jack’s 2014 series What is the value of water, if it doesn’t quench our thirst . . . marks a shift in her practice toward the figuration of the black woman’s body in the Caribbean landscape and suggests that these concerns are also an integral aspect of the salt works discussed in this essay. ↩

- Jacqueline Bishop, “Unearthing Memories: St. Martin Artist Deborah Jack,” Calabash: A Journal of Caribbean Arts and Letters 2, no. 2 (2003): 95. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Krista Thompson, An Eye for the Tropics: Tourism, Photography, and Framing the Caribbean Picturesque (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 5, 12. ↩

- Tiana Reid, “In Conversation with Deborah Jack for SITElines: Unsettled Landscapes,” ARC, September 1, 2014, http://arcthemagazine.com/arc/2014/09/in-conversation-with-deborah-jack-for-sitelines-unsettled-landscapes/. ↩

- Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson, “Afrotropes: A User’s Guide,” Art Journal 76, nos. 3–4 (Fall 2017): 7–8. ↩

- Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, The Affect Theory Reader (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 2. ↩

- Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 34–35. ↩

- Eugenie Brinkema, The Forms of the Affects (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 31–33. ↩

- Ibid., 21, 36. ↩

- Hershini Bhana Young, Haunting Capital: Memory, Text, and the Black Diasporic Body (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2006), 77. ↩

- Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 20–21. ↩

- Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (Summer 1987): 67. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Fabian Bandejo, “Sint Maarten: The Dutch Half in Future Perspective,” in The Dutch Caribbean: Prospects for Democracy, ed. Betty Sedoc-Dahlberg (New York: Gordan and Breach, 1990), 190. ↩

- J. Hartog, History of Sint Maarten and Saint Martin (Sint Maarten: Sint Maarten Jaycees, 1981), 21; Kwame Nimako and Glenn Willemsen, The Dutch Atlantic: Slavery, Abolition, and Emancipation (London: Pluto Press, 2011), 65. ↩

- Bandejo, 121; Ank Klomp, “Bonaire within the Dutch Antilles,” in Sedoc-Dahlberg, The Dutch Caribbean, 107. Bonaire, another Dutch Caribbean island used in Jack’s salt works, harvested 348,020 tons of salt in 1984. ↩

- Gert Oostindie, Paradise Overseas: The Dutch Caribbean; Colonialism and Its Transatlantic Legacies (Oxford: Macmillan Caribbean, 2005), 1. ↩

- Ibid., 13. ↩

- Yet, the terms of emancipation in Sint Maarten were unique within the kingdom due to its shared border. After slavery was abolished in the French Empire in 1848, enslaved people on Sint Maarten responded by declaring themselves free, and they remained in this liminal state of (un)freedom until general emancipation in 1863. This quiet rebellion is indicative of a larger, systemic ambivalence toward the Dutch enslaved population and had lasting consequences for slaveholders on the island, who were offered a significantly lower sum in compensation for their “lost property” after emancipation than slaveholders on the other five islands (see Oostindie, 36; and Bandejo, 121). ↩

- Oostindie, 13; Nimako and Willemsen, 82. ↩

- Bishop, 95. ↩

- Brinkema, 33. ↩

- Bishop, 93. ↩

- Ibid., 95; Hortense Spillers, Black, White, and In Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 155; Alexander G. Weheliye, Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 43–44. My conception of a feminine black ontology is rooted in Hortense Spillers’s theorization that “black is vestibular to culture.” As interpreted by Alexander G. Weheliye, “being vestibular to culture means that gendered blackness . . . is a passage to the human in western modernity.” Within Western history, then, the ontological status of the black woman has been central to the categorical construction of humanness while also being excluded from and existing outside of it. ↩

- Bishop, 93. ↩

- Ibid., 94. ↩

- “The Legend of One-Tété Lohkay,” Daily Herald (Sint Maarten), July 3, 2012. ↩

- Mary Prince, The History of Mary Prince (New York: Penguin Books, 2004), 19. ↩

- Ibid., 13. ↩

- Drisana Deborah Jack, skin (Philipsburg, Saint Martin: House of Nehesi, 2006), 27, 28. ↩

- Brinkema, 10. ↩

- Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 12. ↩

- Ibid., 22. ↩

- Ibid., 6. ↩

- For more on the sonic affects of photography, see Tina Campt, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012). ↩

- Meredith M. Gadsby, Sucking Salt: Caribbean Women Writers, Migration, and Survival (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006), 3, 175. ↩

- Sandra Firmin, “Deborah Jack’s SHORE,” Art Papers 29, no. 1 (2005). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Young, 76. ↩

- Ibid., 78. ↩

- Chambon, Le commerce de l’Amérique par Marseille . . . (Avignon: 1764), 400–401. ↩

- Theodore Weld, American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1839), 23, 60–61, 65, 92. ↩

- Ibid., 29–32. ↩

- Young, 74. ↩

- Ibid., 75. ↩

- Ibid., 81. Emphasis mine. ↩

- Massumi, 25. Massumi theorizes the “intensity” of a given image’s affect as “embodied in purely autonomic reactions most directly manifested in the skin—at the surface of the body, at its interface with images”; intensity is the excess of affect, “a nonconscious, never-to-be-conscious autonomic remainder” (ibid.). ↩

- Here, Krista Thompson’s exploration of the political and aesthetic functions of the picturesque in Jamaican photography is crucial. In her argument, the picturesque “referred to the landscapes’ conformity to these exoticized and fantastic ideals of the tropical landscape. The picturesque denoted a landscape that seemed like the dream of tropical nature” (Thompson, An Eye for the Tropics, 21). ↩

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 7. ↩

- Ibid., 8. ↩

- Stephen Best, “Neither Lost nor Found: Slavery and the Visual Archive,” Representations 113, no. 1 (2011): 160. Here I emphasize what I argue is Jack’s interest in redress through materiality and embodiment in the present rather than a reclamation or excavation of slavery’s unrecorded histories through critical fabulation. I heed Stephen Best’s argument that the relative paucity of slavery’s visual archive has led to a scholarly drive to unearth and (re)discover any remnants that combat this material lack. ↩

- Brinkema, 10. ↩

- Huey Copeland, Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 205. ↩

- Ibid. ↩