Filmed in an apartment on the seventy-seventh floor of Trump World Tower and initially exhibited at Postmasters Gallery, New York, in October and November 2016 (overlapping with the US presidential election), Jennifer and Kevin McCoy’s video BROKER examines the pathological underpinnings of “superluxury” dwelling and its place within the broader culture of capitalist achievement.1 The twenty-six-minute-long looping video centers on the activities of a high-end real estate broker, played by Gillian Chadsey, who appears trapped in a never-ending tragicomedy. Each morning she meticulously prepares for a client walk-through that will invariably leave her in a state of disarray. The first part of her daily ritual involves carefully reciting the sumptuous details of the residence and its furnishings and appliances. At one moment, she enters a trancelike state while various marketing platitudes spill from her lips to the sounds of a vexingly placid score composed by musical artist Lori Scacco. “Influencing others isn’t luck or magic, it’s a science,” her auto-tuned voice sings. “There are proven ways to help make you more successful as a marketer or politician.” Throughout the video we are provided glimpses of the apartment from the point of view of cameras embedded throughout the space—components of an elaborate security system. One of them even captures the character of the broker from inside the designer fridge, as she carefully adjusts bottles of “Pellegrino sparkling” and “Evian flat.” Nothing in this environment exists separately from the value bestowed upon it by its brand or perceived luxury.

According to Nina Power, the present-day “paradigmatic image of achievement” is to be found in the “young professional woman beam[ing] down at us from real estate billboards.”2 And, indeed, the broker in the McCoys’ video, who appears intent on utterly internalizing the speech and gestures of her vocation, is a shining emblem not only of the upwardly mobile workingwoman in today’s society but also of late-capitalist professional achievement more generally. Over the course of the video, however, she will also come to embody the physical and psychological tolls engendered by the ceaseless demands of “entrepreneurial subjectivity”—of being conceived of as being on the clock.3 Despite the broker’s remarkable conformity to professional ritual, her performance eventually devolves into a series of failed gestures. Ultimately, her position within the video can be thought of as a kind of limit case for the subordination of the body and its affects to the demands of contemporary hyperprofessionalization.

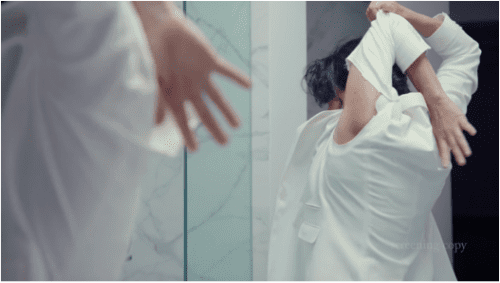

The much-anticipated client walk-through she finally performs for the camera is interrupted when she happens upon a number of out-of-place artworks, which crop up as reminders of the messy world beyond the apartment’s secure boundaries. Suddenly, the spell cast by the discourse of achievement is broken. The broker enters a state of bewilderment and ataxia. For a fleeting instant, she seems intent on rebelling against the strictures of her professional life. She takes vengeance on her neatly pressed blazer, tearing its sleeves off through a series of erratic gestures. But her professional existence, it is now confirmed to us, is her only existence. The language of luxury marketing is the only language she speaks. As the day comes to a close, the broker sits on the edge of the bed, spent, somnambulistic, but still droning on about the empowering attributes of the architecture around her.

Soon, the video returns to the beginning of its cycle. We see the broker’s hands arranging a series of brochures with the Trump Organization logo printed on them. Her voice, which has resumed its professional tone, can be heard over a series of establishing shots of the apartment: “Let us look at the facts of luxury, the incredible resources brought here, deployed here, at this time.” It is an invitation that strikes us as coming from not only the salesperson but also the artists themselves, as though they were beckoning us to contemplate the greater ramifications of the excesses on view.

In what follows, I’d like to take up this invitation to “look at the facts of luxury” by examining two interrelated aspects of the McCoys’ work: (1) the architecture of the apartment in which it is set (along with the significance of high-end architecture more generally within the video); and (2) the objecthood of the luxury consumer products and artworks that appear within the video and that, to some extent, compose its supporting cast of characters. In looking carefully at the aforementioned “incredible resources” arrayed before us and the role they play in structuring the protagonist’s existence, my aim is to offer a provisional account of the type of subjectivity interpellated by the highest reaches of luxury culture. As we will see, it is a subjectivity that is both evacuated of internal ambivalence—of any impulse that might disrupt the seamless logic of marketing and consumption—and, at the same time, one that is susceptible to destabilization from the slightest infiltrations of alterity. This has consequences for how we might conceive of the allegorical value of BROKER vis-à-vis the tense historical and political context in which it was initially exhibited. The fact that the video is set within a Trump-branded building and was on display at the time of the 2016 election tempts us to read the work through a political lens. Yet, far from being a straightforward critique of any single individual or movement, the McCoys’ work provokes circumspect consideration of the political entities it subtly invokes, even as it paints a ghastly picture of the culture of acquisitiveness that has more generally defined our era.

Architecture

For more than two decades Brooklyn-based couple and artistic collaborators Jennifer and Kevin McCoy have been concerned with the relationship of the body to the spaces it interacts with and inhabits. The duo’s installations, sculptural miniatures, and videos have explored the psychogeography of suburbia, airports, art spaces, shopping malls, luxury resorts, and Silicon Valley tech campuses. In recent years, their work has focused on the alienation and environmental degradation engendered by capitalist development. BROKER follows the McCoys’ Eichler Series (2014)—a sculptural mash-up of the architecture of various corporate headquarters buildings and Joseph Eichler–designed middle-class houses—in exploring the contemporary imbrications of commerce and dwelling. Among the cultural developments scrutinized in the video is the phenomenon of the contemporary “starchitect.”

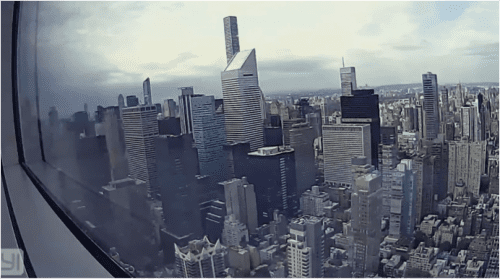

BROKER was shot at Trump World Tower, an unremarkable skyscraper located at 845 United Nations Plaza in New York City and designed by Costas Kondylis, one of Trump’s “go-to” architects. The broker in the McCoys’ video, however, attributes the building to “Pritzker Prize–winning architect Christian de Portzamparc.”4 This misattribution can be read as a subtle slight directed not only at de Portzamparc, the more reputable architect (whose buildings, at the very least, tend to evoke a visual fascination that Kondylis’s do not), but also at the validating institutions of an architectural-industrial complex that sees its star figures as transcending the vacuous symbols of status to which they are often reduced in the context of real estate transactions. De Portzamparc is an interesting figure in this regard, as someone who early in his career designed public-housing projects and cultural centers before graduating to the corporate headquarters of Louis Vuitton and condos for those who can afford such luxury brands. Almost nowhere is the decadence of twenty-first-century architecture more visible than in de Portzamparc’s One57, a residential skyscraper that appears more than once within the dramatic skyline visible through the floor-to-ceiling windows of the apartment in the McCoys’ BROKER. Situated on “Billionaires’ Row” on Fifty-Seventh Street in New York City, One57 was briefly the most glamorous building in a neighborhood that, prior to the completion of Hudson Yards, was the city’s reigning poster child for confused civic priorities.5 It would be reductive to posit, on the basis of one example, a stark dichotomy between a supposedly utopian architectural modernism, which sought to change the world around it, and a postmodern architecture subservient only to the machinations of capital. Yet one can hardly ignore how the arc of de Portzamparc’s career reflects architecture’s shifting ambitions in the postwar period. To borrow a remark by Reinhold Martin, whose scholarship has emphasized the haunting of postmodern architecture by the specter of modernism, the work that de Portzamparc is best known for today is of a variety that may well have “finally succeeded in exorcising Utopia’s ghost.”6 BROKER responds to the consequences of this development for contemporary experiences of dwelling.

On the Pritzker website, de Portzamparc describes his creative evolution in terms that are consistent with the antiregulatory rhetoric of personal liberty and choice used to justify the displacement of social-welfare planning by market-driven capitalism.7 “Architecture seemed to me to be too bureaucratic, and not free enough compared to art,” he remarks, “and the modernistic ideals which I worshiped before, seemed to me unable to reach the richness of real life.”8 In BROKER, the liberal individualist ideology underlying such sentiments is reflected in the on-screen descriptions of the dwelling space: “Here we can let go of the old idea of politics,” the broker tells us; “here we can move beyond the geometry of institutional limits” and toward an “infinity of possibility. . . . The use of space empowers relentlessness. Each element propels you toward your greatest moment.” As at least one reviewer of the McCoys’ fall 2016 Postmasters exhibition observed, this language, making reference to a Trump-branded building, also shares something with the anti-institutional rhetoric used by now-president Trump himself on the campaign trail.9 More immediately, it might be compared to the “truthful hyperbole” that Trump has used to market his high-end residences for more than three decades. “People want to believe that something is the biggest and the greatest and the most spectacular,” reads a line from Trump: The Art of the Deal, a book published when Trump was still principally known as a real estate developer. In Trump’s words, the secret to success is simple: “play to people’s fantasies.”10

Architecturally, Trump’s strategy of playing to fantasy has translated into a development portfolio that is so lacking in any governing aesthetic vision that Ian Volner has described it as “a horrifying asymptote or lacuna in the middle of capital.” Yet, as Volner seems to begrudgingly acknowledge, it is those Trump Organization buildings that are defined by what he terms their “gold everywhereness”—the excessive incorporation of showy, polished reflective materials—that have had the greatest purchase on the popular imagination.11 They have certainly captured the sordid fascination of Trump’s critics. Associating the “streaky shiny marble and drippings of fine piss-yellow gold” that adorn numerous Trump-branded buildings with their owner’s sexual proclivities, writer Sam Kriss offers a memorable vision of the president as a urine-fetishizing neurotic.12 Artist Liam Gillick rejects facile invocations of “dictator chic” in his own brief but exacting excursus on Trump tower, but the quote from J. G. Ballard’s High-Rise (1975) with which he concludes his text affirms the relationship between obscene fantasy and the surplus of logo-emblazoned glass and brass he takes pains to describe: “Secure within the shell of the high-rise, like passengers on board an automatically-piloted airliner, they were free to behave in any way they wished, explore the darkest corners they could find.”13 Perhaps it is notable, then, that in the stark spatiality of the apartment in the McCoys’ video, and even in the broker’s hyperbolic descriptions of the residence as offering an “infinity of possibility,” one encounters something altogether more aseptic. It is not just that the more vulgar trappings of Trumpian glitz are nowhere in sight. It is that the sense of outrageous deviance, of “pure unrestrained and unfiltered id,” that has come to be associated with Trump feels absent or muffled.14 The droning tone of the broker’s voice, in this segment of the video, contributes to the sense that the vision of excess on display here is one that has been drained of vitality, leaving only a coldly abstract or mathematical idea of limitlessness.

Michael Sorkin has remarked on the similarities between Trump’s and Hugh Hefner’s relationships to women, architecture, and “leisure-oriented consumption,” but the Playboy Penthouse this is not.15 The latter, in Paul B. Preciado’s account, was “designed to endlessly convert work into leisure.”16 An office-like space that could seamlessly shape-shift into the ultimate seduction pad, it offered its (white, male, heterosexual) owner a transgressive reprieve from “his suburban house and his lawn.”17 In BROKER, by contrast, the notion of leisure has been entirely subsumed by work. The apartment, as it is presented to us, is geared not toward allowing its inhabitants to transition out of their business attire whenever the moment strikes but rather toward perpetually “empowering” and “propel[ing]” them to the sorts of abstract heights that are only evoked with a straight face in corporate managerial contexts. The only person who can be said to inhabit the apartment, and who thus serves as a kind of surrogate for its would-be owner, is the broker herself—and her life is the very antithesis of leisurely. In the appointments schedule on her tablet, which we glimpse at one point, the item “relax” is categorized as “work,” while her aforementioned “recitation” of marketing jargon is listed as a “personal activity.” In both instances there is the suggestion of a collapse between personal and professional life that is central to the video’s account of contemporary subjectivity.

In the McCoys’ video, the broker’s grandiloquent architectural-theoretical excursus culminates with an assertion that the apartment is indeed “not a respite,” in the sense traditionally associated with home, but is rather “the center of the vortex.” Which vortex, precisely? And what might this have to do with the idea of limitlessness described above? One answer lies in the broker’s references to the “ever-shifting skyline,” which affirm the old real estate adage “location, location, location” in a manifold way. Critics like Herbert Muschamp and Fabrizio Gallanti have noted that Trump’s buildings are often less perceivable as architecture than they are as signifiers of wealth and achievement.18 In the present context, the relatively unremarkable architectural styling can be understood in terms of architecture’s subversion to the function of conferring a sense of lofty stature and voyeuristic supremacy.19 Perhaps even more than the apartment’s architectural details, it is its view of the city around it and its proximity to the heavens that the broker emphasizes. At one point in the video the broker describes the apartment as a “skybox”; at another point it is “sky couture.” Would-be occupants are given an unobstructed view of a city that, although teeming, has already been tamed, reduced to an image—a snow-globe metropolis—by virtue of the “totalizing” function Michel de Certeau, reflecting on a trip to the top of the World Trade Center, associates with the act of beholding from on high.20

Perhaps more vitally, what the apartment would seem to offer its inhabitants on the basis of this voyeurism is a sense of emplacement within the very heart of the process of capitalist accumulation itself. After all, in the age of what Samuel Stein terms “the real estate state,” the gargantuan forest of luxury buildings that continue to proliferate in Midtown Manhattan at a dizzying rate—and in seemingly direct correlation to the city’s homeless population—is nothing if not a concrete embodiment of the prevailing global economic system.21 If leisure is for losers, and sexual seduction a drain on productivity, at least there is pleasure to be had in watching the most powerful economy in history whirl around you. This, then, is one version of what it means to live at the “center of the vortex,” to feel an “infinity of possibility” all around you. Freedom, as it is posited here, is less a matter of exploring the “darkest corners” of one’s imagination, as per the characters in Ballard’s novel. Indeed, imagination appears to have taken a back seat to the Icarian experience, returning to de Certeau, of “looking down like a god”—and not merely as a tourist fascinated with the sudden legibility of the urban fabric below but as a stakeholder in the great pageant of capital accretion itself. In the culture of acquisitiveness explored in the McCoys’ video, no possession enchants more than this.

But in actuality, who else, other than the broker, are the breathless beholders and observed observers of this spectacle of accumulation that so completely perverts the relationship between architecture and inhabitation, between building and dwelling? One answer may be nobody. Many of the apartments in Trump’s buildings are the property of investors who never intended to dwell in them. As Volner has written, “Emptiness is the leitmotif of the Trump Organization’s portfolio, and it is what makes all its buildings so horrible, so chilling, in a way that has little to do with their architecture.”22 Of course, a similar sense of vacuity—in all senses of the term—could be ascribed to the buildings of any number of luxury development companies operating in cities around the globe. And here it is worth considering Stein’s assertion that the Trump family, throughout most of its history, has been little more than a “loud[er]” and more “vulgar version of the completely normal capitalist developer.” Indeed, the bizarre unevenness of the Trump Organization’s projects, which Volner views as an asymptotic outlier, can just as easily be described as a particularly loud or visible symptom of the greater neoliberalization of urban planning: the process whereby city governments have increasingly collaborated with private developers eager to profit in every crassly speculative way—and often at the expense of aesthetic and civic considerations alike—off of deindustrializing zones and neighborhoods slated for so-called renewal.

This is not to say that the Trump brand, particularly post-2016, doesn’t exude its own troubling connotations. But as Rachel Weber reminds us, Trump’s mode of operating as a developer “shows professional practices common to the development industry” as a whole—practices, that are, in turn, “not situated outside of the system of financial valuation and production [but] are, in fact, constitutive of it.”23 Likewise, if there’s something chilling about Trump’s empty apartment buildings, it is the manner in which they exemplify broader trends within urban speculation. As Fredric Jameson suggests, one of the effects of development in the age of financialization is the encroaching sense that our cities have become so antithetical to human dwelling that even the ghostly traces of what such an activity might have at one time meant are being expunged. “Urban renewal,” he writes, “seems everywhere in the process of sanitizing the ancient corridors and bedrooms to which alone a ghost might cling.”24 The description is apt in light of the apartment in BROKER, even though, as we will see, there is a ghostliness that refuses to be exorcized in the McCoys’ video, just as there is in Jameson’s appraisal of postmodern experiences of dwelling. For now, let us simply note that the would-be exorcists in question are enmeshed in a system and ideology that, as Stein takes pains to articulate, transcends political affiliation and certainly extends far beyond the network of nefarious dictators, media moguls, right wing lobbyists, and third-rate hucksters with whom Trump tends to be associated. Here, another answer to the question above—the question of who is the intended inhabitant of the apartment in BROKER—can be ventured.

A long list of unsavory swindlers now iconic in current-event parlance, from “Russian mobsters” to Paul Manafort, have owned real estate in Trump’s buildings, but the only potential clients we catch sight of in the video—displayed momentarily on the screen of another tablet—are conspicuously of another variety. Hailing from the racially homogenous, Democratic-leaning town of Larchmont, in Westchester County, New York, the “McClintocks” (as their name seems almost to affirm) come off as just the sort of cookie-cutter, high-achieving white suburban “moderates” that largely composed the target electorate of Trump’s opponent in the 2016 presidential election. The brief glimpse we are given of their client profile does two things. First, it reminds us of the incessant suburbanization of New York and other large cities—the implantation into urban contexts of what Sarah Schulman calls “the values of the gated community.”25 Second, it helps us to understand the video as gesturing not only toward Trump and his ilk in its representation of the paradigm of dwelling and achievement we have been discussing but also—insofar as the “McClintocks” can be taken as representative of an entire demographic—toward the liberal, rule-of-law-defending beneficiaries of American professional-class meritocracy. Stein observes that the New York City government has long operated under a “bipartisan consensus” with respect to the engineered inequality and forced displacement (at a rate of one hundred thousand people per year) of its citizens through inherently racist urban policies.26 In this regard Trump’s vile white supremacy is no less connected to the city and industry in which he built his business empire than it is to the rural swaths of “deplorable” country that, one suspects, he had hardly spent much time in prior to his run for president. As BROKER appears to subtly register, the historical unity of the ruling classes is realized in real estate.

Two decades into the twenty-first century, the hypnotic power exerted by the vortex of capital—over ethnonationalists and liberals alike—may seem utterly mundane. It is, however, something that Jameson could still ponder with some befuddlement in his seminal 1991 book on postmodernism, which—it bears mentioning—in no small part grew out of his contemplation of the aesthetic-architectural regime within which Trump’s first signature projects took shape.27 Stricken by the market-fundamentalist frenzy that was just hitting its stride in the mid-1980s, Jameson remarked on how “astonishing” it is that “the dreariness of business and private property, the dustiness of entrepreneurship . . . investment banking and other such transactions”—we might add real estate speculation—“(after the close of the heroic, or robber baron, stage of business) should in our time have proved to be so sexy.”28 Today, it is clearer that we are once again living in a “heroic, or robber baron” era of business (who are Jeff Bezos and the Walton family if not modern-day Fricks and Carnegies?), and as Jameson was quick to realize, the full-scale financialization of the economy has only solidified the hold of the market on the popular imagination.29 But there are other factors involved in present-day capitalism’s powerful allure, factors compelling us to redirect our gaze to the interior attributes of the apartment in BROKER.

Objecthood

Much of the action in BROKER involves the protagonist describing the luxurious things around her. We hear about “white Caesarstone” countertops and the faucets, which are “custom-designed” with “very bespoke detailing” and modeled after “a vintage coffee machine.” Moving through the apartment we see modern furniture, decorative vases, and a perfectly polished chrome teapot. In one corner of the room is a Robert Mapplethorpe monograph, an object about objects. On the coffee table lies a copy of the four-hundred-page volume The World in Vogue: People, Parties, Places, in case there was any confusion about the global culture of luxury into which we have entered.

This rarified vision of dwelling is understood to be all the more alluring by virtue of its advanced technological features—from the appliances, which are “of the highest grade,” to the aforementioned surveillance system and other “smart” devices allowing the resident to precisely calibrate their living environment to their needs. Jameson suggests that the “technological bonus of pleasure” afforded by the new consumer gadgets that began to flood the markets at an unprecedented rate (around the same time that “the market” itself took on a newfound fascination) is of such a nature as to necessitate a new category of consumption. He calls this new form of consumer enjoyment “the consumption of the very process of consumption itself” (a thing familiar to anyone who has gazed at a screen just to admire its picture quality), and he posits it as integral to the success of consumer capitalism.30 Arguably this type of consumption is not unique to new technological products. But it is hard to deny that advanced consumer technology today serves as the primary apparatus through which capitalism insinuates itself into fantasy—its mesmeric, seemingly self-validating “miracles” encouraging what Jameson describes as a euphoric “surrender of human freedom to a now lavish invisible hand.”31 In our contemporary moment this is exemplified by what Jonathan Crary describes as the eclipse, by the “attention economy,” of what was “once called the everyday.”32 Increasingly, there is hardly a moment in which existence is not subject to technological capture and, therewith, forces of monetization that grow more insidious all the time.

Such is the condition of domestic life heralded by the “Internet of Things,” which promises to transform the entirety of inhabited space into a digitally networked system. In the quasi-futuristic world of BROKER we are provided a glimpse of this new form of domesticity. As the video’s protagonist tells us, the apartment’s luxury-brand appliances (“Viking,” “Miele,” “La Cornue”) are “all completely connected to the network, to your mobile devices, to you.” In such a context, architecture—already subject, in the age of the contemporary starchitect, to the principle of “brands over products” and subverted to the value bestowed upon it by the real estate market—need only facilitate access to various sites of consumer ritual, defined increasingly by the second-level enjoyment of consuming “consumption itself.” The homeowner hardly needs to look out the window, for here—encircled by miraculous objects, propelled by each element toward their “greatest moment”—they are already at the center of the vortex.

“To live inside fantasy” was the project Rem Koolhaas associated with Manhattanism more than four decades ago.33 Whether or not there was ever any utopian thrust to this project, what BROKER helps us to see is both the mesmeric power and the frightening vacuity of its contemporary manifestations. The video’s achievement lies in part in its allowing us to observe askance—to see the performative dimension within—the spectacle that is superluxury dwelling. There is a creeping unease produced by the McCoys’ video that is similar to that produced by the picture-perfect dwellings and automaton-like inhabitants of the fictional town in the 1972 novel The Stepford Wives. This owes as much to BROKER’s cinematic language as to Chadsey’s dead-eyed smile and tranquil delivery. Especially unsettling is the work’s initial transition from depictions of its protagonist carrying out her drab professional duties to the longer of the video’s two musical numbers—a segment in which the broker addresses the camera directly as the unearthly synth chords of Scacco’s soundtrack swell and a dolly zoom further disorients our senses. In the figure of the hypnotized salesperson/hypnotist we glimpse a terrifying closure of the subject within its system of prestige-bestowing objects. When the interlude concludes, and the broker returns to tidying up the apartment, it is difficult to see the space in the same way. One senses a maleficence lurking beneath the “herringbone parquet floors.”

BROKER is obviously not the sort of materialist account of the production and global circulation of commodities that one finds in the work of artists as different in their approaches as Allan Sekula and Amie Siegel. Quasi-fictional rather than documentary, its focus is not directly on the social forces underlying the availability of the luxury goods it spotlights but on the discourses and affects surrounding their consumption. One can nevertheless assert that the objects in the McCoys’ video, like the art and objects of empire that W. J. T. Mitchell has analyzed, represent “all the crafts, skills, and technologies that make imperialism possible”; that they are, indeed, a kind of “synecdoche for . . . the whole Borgesian archive of empire,” and thus for the very idea of empire itself. To wit: “the total domination of material things and people, linked (potentially) with totalitarianism, with ‘absolute dominion,’ the utopian unification of the human species and the world it inhabits; or the dystopian spectacle of total domination, the oppression and suffering of vast populations, the reduction of human life to a ‘bare life’ for the great masses of people.”34 Insofar as this is registered in the video, it is, once again, by way of the broker’s sales pitch. With rehearsed delectation, she offers the would-be owner and heavenly sovereign a vision of the “unification” of material belongings and subjectivity, as well as of technology-abetted control or “dominion” that is no less than imperial. It furthermore cannot be forgotten—particularly considering the immediate urban geography referenced in BROKER—that this promise of empowered “relentlessness,” like the larger project of empire of which it is a part, is bound up with vast immiseration.

Of course, in the age of Trump, any discussion of the objects of empire is likely to conjure such blatantly exploitative excesses as big-game trophies or blood diamonds, the respectively banned hunting and sales of which the president has taken measures to once again allow. It might also provoke consideration of the imperialist fantasies suggested by the oversize period furniture that decorates the president’s own Trump Tower apartment.35 As we already know, however, this is not that kind of space. Perhaps the closest we get to any overtly scandalous sense of excess is the Robert Mapplethorpe book, and its contents remain safely stored away between its book covers. Moreover, the very fact that it appears in the apartment should indicate to us, once again, that we are within a space outfitted to appeal less to the sordid Trumpian imagination than to the globe-trotting, Vogue-reading liberal: the sort of people who know that the spoils of empire are meant to be tastefully concealed beneath a patina of decency, the aegis of global foundations, diplomacy, philanthropic efforts, and things of that nature.36 The sort of people, for instance, who might organize to have Trump’s name removed from the face of their apartment complex, as the tenants of New York’s West Side Highway–facing Trump Place did in the wake of the presidential election, and then celebrate the successful mitigation of their shame as an “empowering act of protest,” while continuing, quite shamelessly, to talk up the building’s “impeccable” services.37

In the news item just cited, which was circulated giddily on liberal social media in the wake of Trump’s election, one catches a whiff of the “horrifying hypocrisy” Georges Bataille associated with the ruling class of his own era for presuming that it might be “capable of acceptably dominating the poorer classes,” so long as it managed to exhibit restraint or, in his phrasing, “maintain sterility” with respect to its visible excesses.38 What BROKER affirms is that, in the world of superluxury, even the most sterile expenditures come at a cost that is more than monetary. The “sky couture” before us may be tasteful enough in its unobtrusiveness, but the subjectivity it indexes and interpellates is troubling precisely for the manner in which it equates morals with good taste, the right sort of expensive coffee-table book, designer brand, or luxurious apartment complex.

Here it is worth recalling Hal Foster’s essay “Design and Crime,” an early twenty-first-century update of Adolf Loos’s “Ornament and Crime.” As Foster argues, the “world of total design” birthed at the turn of the nineteenth century and reenvisioned according to modernist principles has, in actuality, only reached its zenith “in our own pan-capitalist present.” Today, everything from domestic interiors to the drugs people take to the DNA they pass on to their children bears a “designer” label. And, as Foster observes, it is often the name on the product as much as the thing itself that the consumer of luxury goods desires and identifies with, performing “a self-interpellation of ‘hey, that’s me’” each time they catch sight of their brand.39 The effect of all this increasingly abstracted objecthood on subjectivity, according to Foster, is “the production of a new kind of narcissism, one that is all image and no interiority—an apotheosis of the subject that is also its potential disappearance.”40

It is just such an apotheosis that the protagonist in BROKER embodies, not only by virtue of the luxury brand names and marketing platitudes that make up the extent of her vocabulary but also through her very gestures, which have been purged of all but the faintest traces of spontaneity. The staged apartment, for its part, shows no signs of living inhabitants. Walter Benjamin’s scattered remarks on the birth of interior space and bourgeois dwelling feel appropriate in theorizing the subjectivity evinced here. “To live means to leave traces,” writes Benjamin.41 While the “soulless luxuriance” of the apartments that figure in nineteenth-century detective fiction may have been “true comfort only in the presence of a dead body,” they were nevertheless filled with objects designed, so long as their doomed occupants were alive, to emphasize their living movements.42 Indeed, for Benjamin, it was precisely through the “abundance of covers and protectors, liners and cases,” on which the “traces of objects of everyday use” can be observed, that the forensic imagination of Edgar Allan Poe and his successors came into being.43 In BROKER this dialectic of life and death is sublated into the protagonist’s day-to-day existence, which is lifeless in a strict Benjaminian sense. When the broker is not subordinating her speech to the “soulless luxuriance” around her she is busy maintaining the pristine presentability of the space, which means perpetually erasing all traces she has left within it. Over the course of the video we see her polishing the mirror in the bathroom, arranging pillows on the couch, and picking fuzz from the carpet. This obsessive enactment of household duties traditionally associated with women’s work, which parallels the broker’s meticulous self-maintenance and maquillage, can be understood as registering the asymmetric pressures placed on professional women, even within a cultural context in which, to quote Nina Power, “all work has become women’s work, even that of men.”44 At the same time, her efforts to keep every designer-branded surface of the apartment in pristine, merchandisable condition contributes to the impression that this is an interior space suitable for a subject that—irrespective of gender and its masquerades—is “all image and no interiority.”

Importantly for the McCoys’ commentary on our cultural moment, this also means that this interior space is one that is unsuitable for art—at least for any art not immediately reducible to its value as a luxury item (or concealable within the pages of a coffee-table book). Reflecting on the emergence of “thing theory” and the broader interest in material culture that took hold at the start of the twenty-first century, Mitchell observes that “objecthood . . . seems to have decisively triumphed over what [Michael] Fried understood to be art.”45 In the present context, that triumph must be understood as coextensive with the triumph of the particular object that is the commodity. In its extreme form, such a triumph implies the elimination of the autonomous artwork: the reduction of aesthetic value to market value, or, at best, to design value—to a given work’s complementary capacity within a preconceived scheme or system. As a work in which luxury consumer products vie for the leading role, BROKER helps us to visualize this “total” order of commodity-things. But it also places in question this order’s totalizing potential. As the work crescendos, we see that the broker’s efforts to maintain the space in its hermetic perfection are unsustainable. When a series of unplaceable pictorial artworks appear within the apartment, seemingly out of nowhere, the pristine world before us begins to crumble. What the McCoys’ video therefore appears to imply is that the full emergence of commodification ironically conditions the return of art as a potentially destabilizing force.

Here we can refer to Nicholas Brown’s work on the “real subsumption” of art under capital. Brown argues that under present-day neoliberalism, “the assertion of [artistic] autonomy” in relation to the culture industry—which was essential to modernism but antithetical to postmodernist pastiche—“becomes vital once again.” Moreover, whereas modernism’s relation to the market can be understood, retrospectively, as “nothing other than a deeper commitment to classical political liberalism,” manifest through the establishment of a “restricted field” of autonomous expression within the broader cultural sphere, art nowadays faces its potential commodification—insofar as it faces it at all—in a more directly antagonistic manner. “Autonomy today,” writes Brown, “is locked in a life or death struggle with the market.” The vitality of the autonomous work of art depends upon its ability not only to cut against the gravitational pull of the market or surreptitiously repurpose popular cultural forms but also to mediate its relationship to the wider political economy in such a way as to produce—at the very least—a “minimal” counterpolitics.46

This is effectively the stage onto which the art object enters in BROKER—only we have to envision here a market that has already claimed victory in a way that is at once more decisive (if possible) than in our own era and, by virtue of this decisiveness, Pyrrhic. For the world of BROKER would seem to be one in which any expression of the semiautonomy of the artwork, its merest resistance to prevailing structures of codification, is a threat to the coherence of the system as a whole. The artworks that appear, unexpectedly, within the more private recesses of the apartment, as though born into being through a chink in the repressive armor of luxury culture, are only minimally disturbing. (In the bathroom is a painting of a man with blood pouring from his head; in the laundry closet is a work depicting a face smeared with a pinkish substance.47) But they resist easy assimilation into the protagonist’s lexicon of “very bespoke” attributes and thus register less as objects than as “things”—sources of destabilizing ambivalence.48

What is essential here is not so much the nature of the objects themselves, which hardly fit into the categories of “positive historicism” or “aestheticization of genre” that Brown offers as worthily autonomous challengers to the “heteronomy” of the market. It is rather the way in which these objects—embedded in a work that is, indeed, “a theory of itself” in the sense Brown argues is necessitated under present conditions—are made to figure an unassimilable remainder within an otherwise totalizing system. Their uncanny emergence suggests that for all the seeming implausibility of autonomy in our market-dominated era, it is, rather, as Brown asserts, “the claim to universal heteronomy that is implausible.”49 In this sense, for all of the work’s apparent pessimism regarding the ever-escalating obsession with material accumulation and the reduction of the everyday to consumer ritual, BROKER invests the work of art with an estimable power to interrupt the dominant paradigms of desire and consumption, staking a claim to its own autonomy in the process.

Ultimately, the notion that there is an unassimilable remainder to the operations of the market is reflected in the gestures of the broker herself. The appearance, in the apartment, of the unplaceable art-object-Thing disarticulates not only the system of objects the protagonist has taken such care to describe but, with it, the subjectivity that has been molded by that system.50 From the moment the video’s protagonist catches sight of the artworks, her carefully rehearsed professional routine is thrown into disarray. She undergoes the bout of bewilderment, proprioceptive breakdown, and fleeting refusal that I described at the start of this essay. In this moment, she bears testament to the minimal difference that prevails between her being and the vision of total subjectivization she had earlier embodied. How, finally, are we to understand this moment of disturbance vis-à-vis the immediate political context surrounding the McCoys’ video?

Breakdown

For those who viewed BROKER at Postmasters Gallery in the aftermath of the 2016 election, when protestors were gathering in front of Trump Tower on a nightly basis, the video might have seemed to possess an unsettling prescience. In its portrayal of a hypersurveilled, consummate professional woman who, despite her exhaustive preparation, is undone at the pivotal moment, the work anticipates what is—along with 9/11 and the 2008 market crash—the most significant glitch in the institutional logic of twenty-first-century US history. The pressed jacket worn, and later torn, by the protagonist in BROKER already rhymes unavoidably (if unintentionally) with the all-white suit worn by Hillary Clinton at the Democratic National Convention in a purported nod to the women’s movement. Roughly two weeks after the video’s premiere, the breakdown it depicts would be echoed by Clinton’s bewildering downfall. In the lead-up to the election, the former First Lady, senator, and secretary of state, whose prior life had seemed nothing if not a long rehearsal for the role of president, would find herself, like the broker, lost in a Trumpian funhouse, turned about in a vertiginous echo chamber of empty slogans and “truthfully hyperbolic” sentiments. If BROKER is foremost a response to the culture of professional achievement in general, it nevertheless lends itself, once again, to considerations of the particular place of women’s labor within a prejudicial social sphere that still privileges male dominance. In this regard, the work might be read in relation to the labyrinth of culturally ingrained antagonisms and expectations that Clinton had to negotiate in her efforts to upend the most patriarchal of institutions.

As the preceding analysis has already demonstrated, however, the video’s implicit criticisms of the society it references are more complex than they might initially appear. First of all, we cannot forget that the spatial physiognomy of the apartment in the video is decidedly un-Trumpian, at least in the obviously vulgar sense. Rather, it reflects the taste of the “McClintock” liberals among whom, it is often forgotten, Trump himself has spent much of his life hobnobbing. Second, insofar as BROKER foregrounds the technocratic mindset, with its smug credentialism and devotion to supposedly “scientific” strategies for success, the video’s commentary by no means limits itself to the world of commercial achievement. It may also be extended to professional political culture and perhaps particularly to the American liberal establishment, with its unshakable faith in focus groups and poll testing and its seeming inability to navigate outside a set of predetermined gestures—to so much as entertain a realm of possibility beyond the bounds of its narrowly concessionary political imperatives. In this sense, the automaton-like protagonist in BROKER, whose hermetically interpellated existence is ruptured by the merest glimpse of alterity, anticipates the insight, now voiced even by standard-bearers within the Democratic Party, that Donald Trump did not win the presidency so much as Democrats lost it. Faced with a series of unforeseen swerves necessitated not only by the rise of the alt-right but also by a newly energized left, the Democratic Party’s well-greased political machine ran off its rails.

Such parallels may be compelling in their own right. In the end, however, BROKER is more than simply an effective allegory for the 2016 election. It is a searing indictment of neoliberal culture as a whole: its obsession with wealth and achievement and its production of a form of subjectivity reduced to near-total consumer identification. Lauren Berlant has given us the marvelously succinct phrase “cruel optimism” to describe the self-defeating attachments to fantasies of “the good life” we continue to nurture under capitalism in spite of ourselves. But in the superluxury imaginary—the phantasmagoric realm of overexcess, of the excess of excess—we encounter a voraciousness and an object of desire for which terms like “cruel optimism” and “good-life fantasy” seem all too kind. In one of the final images we see before the McCoys’ video loops over again, the broker is shown lapping up a ring of moisture on the coffee table from which she has just lifted a glass of brand-name water, poured for her prospective client. It is as though by imbibing this tiny excess share of transactional exchange she might absorb within her the molecules of luxury itself. Here the catchword “thirsty”—as in “The 13 Thirstiest People of 2017,” a Fast Company article that, unsurprisingly, featured Donald Trump at the top of its list—seems the only appropriate term. The culture of acquisitiveness envisioned in BROKER is one that appears hell-bent on drinking the oceans dry.

What the work nevertheless affirms, if it can be said to possess an affirmative dimension, is that ambivalence remains threaded throughout the damaged and costly psychology it spatializes with such scrutiny. The fantasy of immaculate plenitude is threatened by internal forces that grow stronger from the energy expended to keep them at bay. As in any aseptic environment, the prevailing order of productivity grows vulnerable by virtue of its own excessive decontamination. As much as BROKER models the persistent inculcation of a purely transactional mode of human conduct that is a threat to the human as such, it is also a work about the implausibility of totalization and the uncanny returns produced by capitalist domination. In this sense, the McCoys’ video does more than allegorize the undoing of a Democratic Party whose faith in nineties-era political wisdom blinded it to the seething disaffection of segments of the electorate that have failed to benefit under the prevailing political economy. The work also anticipates larger-scale disruptions in the global order that have already expressed themselves with particular force on the European continent and that, as of this writing, are rocking city streets from Beirut to Santiago. It remains to be seen whether these disruptions will result in genuinely new political alignments, or whether the crisis will pass and the day will begin again, as it finally does in BROKER, with a lifeless smile.

David Markus is an interdisciplinary writer and educator. His work focuses on representations of dwelling and domesticity in late-capitalist contexts, social practices in contemporary art, and the conflict between intimacy and artistic ambition in twentieth-century literature, art, and film. His articles and reviews have appeared in publications such as Art in America, Frieze, Art Journal, Art Papers, and Flash Art. He teaches in the Expository Writing Program at New York University.

- “Superluxury” is a term Donald Trump has long used to describe the mix of high-end design details and amenities that his residence buildings offer to their wealthy clientele. Trump’s particular vision of superluxury brings together commerce and leisure with exclusive dwelling. The website for Trump Tower, which preceded Trump World Tower by two decades, states the former building was “the first super-luxury high rise property in New York to include high-end retail shops, office space and residential condominiums.” See “History: Trump Tower, New York,” Trump Tower website, accessed September 1, 2018. ↩

- Power’s argument is that the generalization, within the professional sphere, of not only the precarity but also the affective labor and carefully choreographed self-presentation traditionally associated with “women’s work” has meant that work, as such, “has essentially been feminized.” See Nina Power, One Dimensional Woman (Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2009), 21, 22. ↩

- This has become a common term for critics concerned with describing life in Western neoliberal contexts. “More and more,” writes Lauren Berlant, “even when asleep, one is never closed for business. This is the pressured affectsphere of entrepreneurial subjectivity, the form of life forced to be on the make.” See Berlant, “On Persistence,” Social Text 121, no. 1 (Winter 2014): 33–37. ↩

- As David Dunlap observed in his New York Times obituary for the architect, Kondylis, who passed away in August 2018, “did not so much have an aesthetic style as a business formula. He provided developers with efficient, marketable, dependable, comfortable buildings. The designs won few prizes or critical plaudits, but they also caused few headaches for those who financed and built them.” Dunlap, “Costas Kondylis, Go-To Architect in a High-Rise Town, Dies at 78,” New York Times, August 24, 2018. ↩

- Developed by diamond-merchant-turned-developer Gary Barnett, whose company Extell has been accused of a range of unscrupulous practices, the largely uninhabited skyscraper is a giant investment-opportunity-cum-tax-shelter. For a discussion of how buildings like One57 operate as tax shelters for the wealthy, see Kriston Capps, “Why Billionaires Don’t Pay Property Taxes in New York,” CityLab, May 11, 2015. ↩

- Reinhold Martin and Jonathan Crisman, “Conjuring Utopia’s Ghost,” Thresholds 40 (2012): 14. See also Reinhold Martin, Utopia’s Ghost: Architecture and Postmodernism, Again (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010). ↩

- David Harvey notes that “it has been part of the genius of neoliberal theory to provide a benevolent mask full of wonderful-sounding words like freedom, liberty, choice, and rights, to hide the grim realities of the restoration or reconstitution of naked class power.” Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 119. ↩

- Christian de Portzamparc biography, Pritzker Architecture Prize website, accessed June 25, 2019. ↩

- Mira Dayal, “Jennifer and Kevin McCoy: Broker,” NYAQ/LXAQ/SFAQ/, November 21, 2016. ↩

- Donald J. Trump with Tony Schwartz, Trump: The Art of the Deal (New York: Ballantine Books, 1987), 58. ↩

- “Ian Volner on the Architecture of Trump,” video, Artforum, accessed April 6, 2019. ↩

- Sam Kriss, “Pissologies,” Baffler, January 17, 2017. ↩

- Liam Gillick, “A Building on Fifth Avenue,” e-flux 78 (December 2016). ↩

- David Martin, “Trump Is Unrestrained and Unfiltered Id,” Huffington Post, August 17, 2017. ↩

- Michael Sorkin, “The Donald Trump Blueprint,” Nation, July 26, 2016. ↩

- Beatriz (Paul B.) Preciado, Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy’s Architecture and Biopolitics (Brooklyn: Zone Books, 2014), 86. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Herbert Muschamp, “Trump, His Gilded Taste, and Me,” New York Times, December 19, 1999; Fabrizio Gallanti, “Blinded by Bling: On the Absence of Architecture in Trump World,” Interwoven: The Fabric of Things, accessed on June 1, 2018. ↩

- Voyeuristic supremacy, it would seem, is something near and dear to Trump. Michael Kruse quotes two separate sources describing Trump as someone who was perpetually “looking down” from his perch in Trump Tower. See Michael Kruse, “How Gotham Gave Us Trump,” Politico Magazine, July/August 2017. ↩

- Of the experience of viewing Manhattan from the top of the World Trade Center, de Certeau writes how one is transformed into “an Icarus flying above. . . . His elevation transfigures him into a voyeur. It puts him at a distance.” See Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life: Volume 1 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 92. ↩

- Stein notes that “global real estate is now worth $217 trillion, thirty-six times the value of all the gold ever mined. It makes up 60 percent of the world’s assets, and the vast majority of that wealth—roughly 75 percent—is in housing.” Samuel Stein, Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State (London: Verso, 2019), 2. ↩

- Ian Volner, “Fool’s Gold: The Architecture of Trump,” Artforum, accessed April 7, 2019. ↩

- Rachel Weber, “Edifice Rex: Egos, Assets, and the Financialization of Property Markets,” Avery Review 21, January 2017. It is essential to Weber’s argument that her analysis of Trump “shows professional practices common to the development industry.” ↩

- Fredric Jameson, “The Brick and the Balloon: Architecture, Idealism and Land Speculation,” New Left Review I/228 (March/April 1998): 45. ↩

- Sarah Schulman, The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 30. ↩

- Samuel Stein, “New York’s Bipartisan Consensus,” in Capital City, 79–115. For relocation statistics, see Noah Manskar, “Over 100k NYers Are Forced from Homes Each Year, Research Finds,” Patch, May 24, 2019. ↩

- For an analysis of Trump Tower via Jameson’s Postmodernism, see Gillick, “A Building on Fifth Avenue.” ↩

- Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991), 274. ↩

- In Jameson’s essay “Culture and Finance Capital,” which proceeds from a reading of Giovanni Arrighi’s The Long Twentieth Century, Jameson explicitly poses a series of questions about the hypnotic power of the market in light of the (by that point) hegemonic reign of the economic system bequeathed by the “Reagan-Kemp and Thatcher Utopias.” En route to a more elaborate analysis of the abstractions and deterritorializations of finance capital, he also provides an insight that—as he is well aware—is as simple and self-evident as it is unsatisfying: we have returned to “the most fundamental form of class struggle.” Henceforth, as far as most of society is concerned, political freedom is market freedom. See Fredric Jameson, “Culture and Finance Capital,” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 1 (Autumn 1997): 247, 246, 247. ↩

- Ibid., 275–76. This paradigm is captured beautifully in a recent Samsung ad featuring a man whose unblinking eyes stare in amazement at a television broadcast of a football game, despite the fact that “he’s more of a golf guy.” See “Samsung QLED TV TV Commercial, ‘Can’t Look Away,’” iSpot.tv, accessed November 11, 2018. ↩

- Ibid., 274. ↩

- Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (London: Verso, 2013), 75–76. ↩

- Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York (New York: Monacelli Press, 1994), 10. ↩

- W. J. T. Mitchell, “Empire and Objecthood,” in What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 154. ↩

- Peter York, “Trump’s Dictator Chic,” Politico, March/April 2017. ↩

- Research into the purchasing habits of Democrats and Republicans confirms a division in the social signaling privileged by each group. The authors of a recent study suggest that Republicans spend more on luxury products and are more concerned with “vertical” hierarchy than Democrats, whereas the latter tend to privilege “horizontal” uniqueness. See “Better or Different? How Political Ideology Shapes Preferences for Differentiation in the Social Hierarchy,” Journal of Consumer Research 45, no. 2 (August 1, 2018): 227–50. It is notable, however, and perhaps indicative of the fact that there is less daylight between Trump and his wealthy liberal counterparts than is often pretended, that Vogue coffee-table books appear to be a staple of Trump’s own lavish Louis XIV–inspired penthouse. See Ben Ashford, “Inside Donald Trump’s $100 Million Penthouse: Gold-Rimmed Cups, a Toy Personalized Mercedes for His 10-Year-Old Son, a $15,000 Book and Some VERY Risqué Statues,” Daily Mail, November 10, 2016. ↩

- Caleb Melby, “NYC’s Trump Place Apartments to Drop Name amid Tenant Outcry,” Bloomberg, November 15, 2016. ↩

- Georges Bataille, “The Notion of Expenditure,” Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927–1939, ed., trans. Allan Stoekl, (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 1985), 125. ↩

- Hal Foster, “Design and Crime,” Design and Crime (and Other Diatribes) (London: Verso, 2003), 19–20. ↩

- Ibid., 25. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” in Reflections, trans. Edmund Jephcott (New York: Schocken Books, 1978), 154, 155. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “One-Way Street (Selection),” in Reflections, 65. ↩

- Benjamin, “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” 154, 155. ↩

- Power, One Dimensional Woman, 22. ↩

- Mitchell, “Empire and Objecthood,” 153. ↩

- Nicholas Brown, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Real Subsumption under Capital,” Nonsite.org, March 13, 2012. ↩

- The painting in the bathroom is by Angela Dufresne; the second work is by Geoffrey Chadsey, who happens to be the brother of Gillian Chadsey, the actress playing the broker. ↩

- “Things,” as Mitchell states, “have a habit of breaking out of the circuit, shattering the matrix of virtual objects and imaginary objectives.” Mitchell, “Empire and Objecthood,” 156. ↩

- Brown, “Work of Art.” ↩

- For an account of the relationship between subject, object, and thing, see Bill Brown, Other Things (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 20–24. ↩