In the summer of 1968, as the Democratic National Committee prepared to roll into Chicago, the city’s Museum of Contemporary Art was entering into an unusual partnership—an “experimental friendship”—with an organization called CVL, Inc. What’s remarkable about this organization was that it was the new incarnation of a notorious street gang known as the Vice Lords. The letters stood for “Conservative Vice Lords.” Called “Westside terrorists” by the Chicago Tribune, the Vice Lords—by their own description—had “ruled the streets” on the West Side.1 “Cars were stocked with shotguns,” they wrote of their past exploits. “Young men were mauled in street battles, and many were arrested and sent to jail.”2 How did such a friendship come to exist? The Vice Lords, like other street gangs in the city, had become interested in working on neighborhood problems in a constructive way; they had “gone conservative,” and reinvented themselves as the Conservative Vice Lords, opening several businesses and sponsoring youth programs. Meanwhile, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) was brand new, and its director, Jan van der Marck, was interested in how museums could make more of an impact in their communities—their entire communities. And so, ever so tentatively, this friendship formed, and produced an experimental art center called Art & Soul, at 3742 West Sixteenth Street in the neighborhood of North Lawndale on Chicago’s West Side.

What place can such a project have in the stories we tell of modern art of the 1960s? If the standard wisdom about that period is concerned, the answer is “not much.” To try a somewhat brutal exercise, let us take the table of contents of Art since 1900 as our guide to what’s considered important in the twentieth century by art history now—and try to imagine a place here for a story like this one. Looking at the chronological table of contents, we would think that African American artists were absent in the fifty years between 1943 and 1993, and that the one thing that happened in art in the entire twentieth century in Chicago is that László Moholy-Nagy died there.

A closer look reveals, as many reviewers have noted, that Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, and Benjamin H. D. Buchloh could not or would not write about the Mexican mural movement or the Harlem Renaissance, so the publisher was forced to outsource those two entries.3 The Black Arts Movement, perhaps the only postwar American art movement distinctly affiliated with anything resembling or calling itself a political vanguard, is entirely absent—undoubtedly because it is perceived (if perceived at all) as a premodernist rather than postmodernist formation. If some artists in Chicago (or elsewhere) were working in a different visual or political idiom than the New York avant-garde, it had to be—by the field’s still-current definitions—because they were behind. If those artists happened to be African American, the impression of belatedness chimes harmoniously, if unintentionally, with dominant white-supremacist narratives.4 If they produced works that weren’t commercial, that haven’t survived (itself anything but happenstance), then there is, further, no financial and institutional compulsion backing them up. Whether the field has unconsciously accepted racist constructions or has rather shown its discomfort with them by looking the other way, art history has often failed to recognize the challenges black artists in the 1960s and 1970s directed not just at entrenched institutions but also at the presuppositions of the white avant-garde.5 From this point of view, it was not just a matter of correcting biased aesthetic judgments and producing appropriate demographic representation. Rather, the critique addressed the central preoccupations with aesthetic autonomy and the avant-garde—preoccupations that, consciously or not, supported (and support) a racist worldview. Art since 1900 is recognizably an extreme, but an extreme that forcefully shapes the landscape of what is possible to think and study about twentieth-century art. What kinds of questions could students whose engagement with the century starts with this book even begin to ask?

In 1950 Clement Greenberg wrote, in an essay on Paul Klee, that the School of Paris “opened our eyes to the virtues of oriental and barbaric art. It became possible to find valid art anywhere in history and geography.”6 Leaving aside the term “barbaric” (coupled quaintly with “virtues”), Greenberg’s caveat to this point is notable: “In painting it was demanded of this exotic material only that it be controlled by the primary and still rather inflexible formal requirements of the easel picture, which remains always a most specifically Western and local art form.” Greenberg thus opens the 1950s with this admission of the ethnospecificity of the easel picture, an acknowledgement that is, to quote Charles Mills on the racial contract, “simultaneously quite obvious if you think about it . . . and nonobvious, since most whites don’t think about it.”7

Along with the Western easel picture, other basic suppositions within modernist art discourse are a monocultural hierarchy of value and the ideology of an identifiable avant-garde: “advanced art,” a single vanguard thread that runs through (or perhaps alongside and stitching into) history. The avant-garde is reputed to be in rebellion against social conditions, yet is by now—indeed was by the 1960s—thoroughly the creature of consumer capitalism.8 These points may seem obvious, but they bear repeating, in a discipline that loves to critique modernist myths yet at the same time seems oddly addicted to them (or perhaps addicted to a market logic for which they provide cover).

I came to this work from two directions: one was the pedagogical imperative to see that my students, studying on the South Side of Chicago, became aware of the rich histories of the arts that exist in their neighborhood, often just outside the university walls. The other was the sense that contemporary practitioners of socially engaged art were missing out, because the histories of their practices have been occluded, on possibilities for solidarities and learning across race, history, and geography. A segregation of knowledge both mirrors and continually produces the persistent segregation of artist and activist communities. Writing on twentieth-century art remains overly dependent, perhaps because and not in spite of the premium it places on “aesthetic autonomy,” on art-market-based institutions. Let me pause here: the continued concern with autonomy, I am arguing, is a screen for a form of dependence. The study of twentieth-century art still seems tethered—or as I said earlier, addicted—to assumptions that are based in the dominant value judgments of the historical period it studies. Since the ideology of the avant-garde and aesthetic autonomy also often buttressed racial and gender hierarchies, they obscure the view of history and our perceptions of what research it might even be possible to undertake. From a phase-shifted point of view, the twentieth century might be seen as a century of reflection, consciously conducted by artists and critics, on the social commitments and responsibilities of art—not just as one of an ever-advancing line of superior competitive strategies.9

A different example of the ways in which the boundaries of art are policed comes in a statement made by Claire Bishop about Tania Bruguera’s experimental art school in Havana, Arte de Conducta. Debating “the status of Arte de Conducta as a work of art,” Bishop writes, “My feeling is that everything will depend on how [Bruguera] documents five years of workshops—as a book, an exhibition, or through the students’ own work. As a live project it’s completely invigorating, but subsequent audiences need to be able to make sense of it.”10 Bishop seems here to be capitulating to external definitions rather than offering up her own—answering the question “Will this be understood as art?” rather than “Is this art?” But these (as Bishop is certainly aware) are two different questions. Indeed, the suggestion that they depend on the same process is somewhat unsettling. It implies that art becomes art—or becomes intelligible as art—only through its representation within specific institutions of art. I take Bishop’s remarks as symptomatic not of her own views but of a position in which she finds herself in dealing with Arte de Conducta. Following the logic of this position, either we must resituate art in objects alone (ephemeral performance becomes art through its documentation in material objects) or imagine that the Cuban art students who are the primary actors and recipients of the project do not actually count as actors and recipients. If the latter is the case, the question is why: are they culturally, politically too far outside the institutions of the Euro-American art world? Or does a state that compels collectivity and collectivism frustrate the attempt to define a collective art project as a critical one? (In its own context, in other words, is education-as-art not enough of an intervention?) Perhaps it is Bishop’s response to the dawning suspicion that she has been othered—as a Euro-American critic, turned by the students into an object of slightly sad curiosity. Perhaps a more embracing way to think about the questions Bishop raises would be to suggest that if art is an intervention into a conversation, we need to have a sense of what that conversation is before evaluating the art. Art is a moment of newness, an event, but one that pushes back against something—whether we call that conversation, as I just did, or medium, institution, or frame. What Bishop reaches for and cannot find is the frame against which Arte de Conducta pushes, and her default is the world of Euro-American art institutions. The remark is an offhanded comment in an otherwise thoughtful body of writing. Yet in its very offhandedness it is symptomatic of more general assumptions and hints at a broader problem in the field: What is the ground against which as-yet-unimagined figures will define themselves? The institutions and discourses of modernist criticism and its postmodern aftermath have provided a convenient and often extremely productive ground for approaching a lot of twentieth-century art. But perhaps it is time to kick the habit.

— — —

Art & Soul was not entirely outside the mainstream art world. It was a point of intersection: between the new aspirations of late 1960s museums and forms of creativity born of the desperate conditions of an African American ghetto; between the young Black Arts Movement and older, established African American artists. At base it may have been just a fresh episode in the history of the periphery of mainstream art institutions. But it was a moment of optimism, coalition, and risk-taking that may have lessons for the future. Institutional politics sometimes produced conflicts; the approaches made by the various parties—the museum, the gang, the broader local community—were sometimes tense. Indeed, the risks taken by all sides were considerable. And though it has been largely forgotten, the project as a whole embodied many qualities now accepted not just as adjuncts to the creation of artworks but as components of the work of art itself. Art & Soul and similar projects might indeed be seen as the precursors to more recent projects that go under the rubric of community art or collaboration or “new genre public art.” But it can be a struggle to see it in this light. It doesn’t fit the standard history of “contemporary” art for a few reasons. It wasn’t the project of a single famous artist or even a famous artist group. It doesn’t fit with the lingering critical notion of the avant-garde and the historico-aesthetic preoccupations that attend it. Its politics were not revolutionary (though they were certainly risky, and that was part of their importance). It doesn’t sit comfortably with narratives of the history of identity politics. To account for stories like this one requires a more expansive notion of the history of the present than art history has yet shown willingness to undertake.11

The Experiment

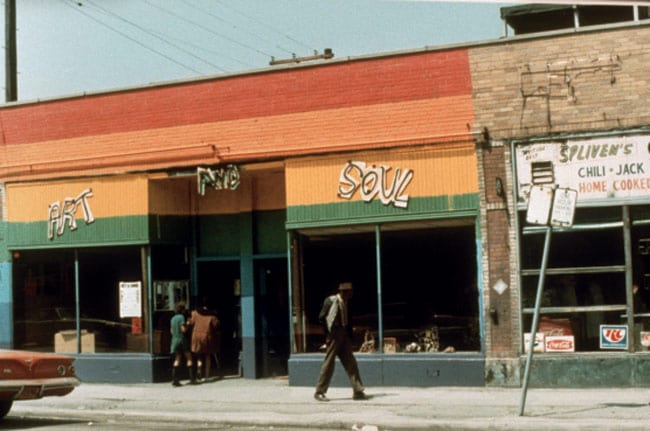

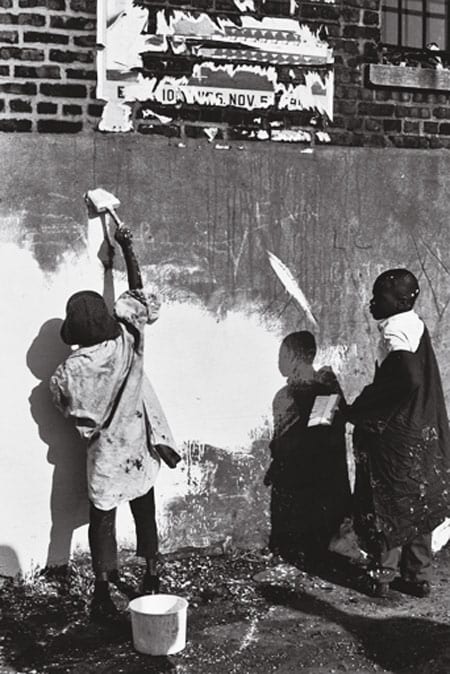

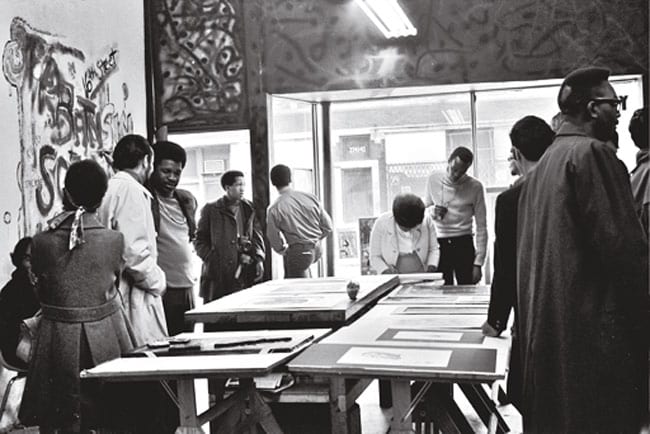

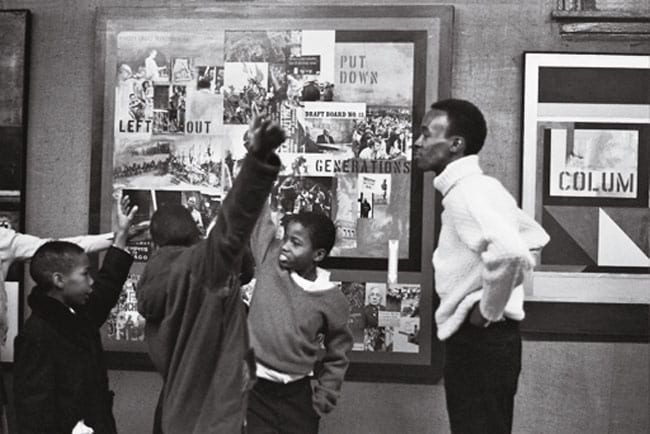

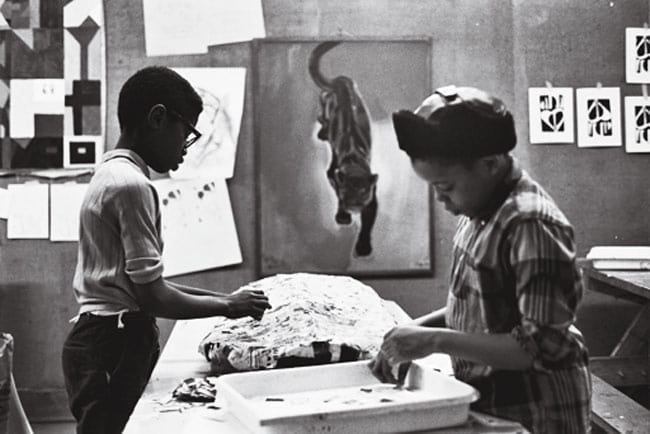

Art & Soul served as a neighborhood art studio with classes for children, a library of books, freely available materials for artists, an artist residency, contests, readings, and exhibitions. Funding from the Illinois Sesquicentennial Commission enabled two storefronts to be joined into a single space, their interiors painstakingly renovated, cleaned, and prepared, and the whole building painted and decorated inside and out. Ann Zelle, a young photographer from Springfield, Illinois, worked on the project with Lawndale artists—the brothers Jackie and Daniel Hetherington, and Peter Gilbert—along with a staffer from the Illinois Sesquicentennial Commission, James Houlihan. Zelle kept copious notes and documented the project photographically. Children were involved from the beginning, painting the exterior walls as renovations began.

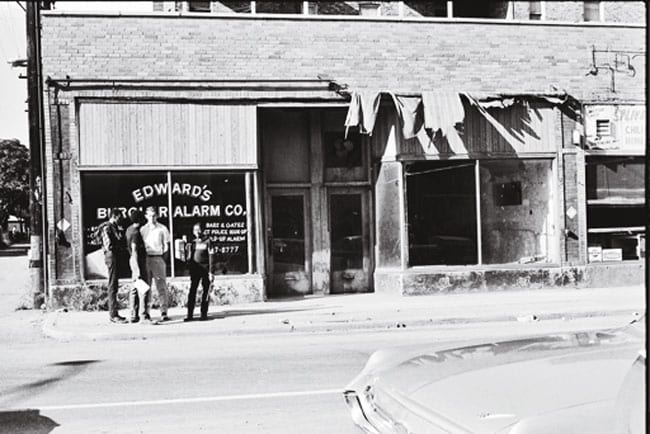

Lawndale was (and is) one of the poorest neighborhoods of the city, and the project sought to bridge the divide between the ghetto and downtown cultural institutions. It was not merely a white outpost; the Hetheringtons, who served as director and assistant director, were members of the CVL organization, and the advisory council included numerous black artists and community organizers. When Art & Soul opened on November 14, 1968, it was full of visitors. Robert Nolte wrote for the Chicago Tribune, “Two months ago, it was a dilapidated building, housing a hat cleaner on 16th Street. Today, it is the brightest spot on the block—Art & Soul, a library, gallery, light and music theater, and workshop for west side artists.”12 Two vacant storefronts (one had been, as Nolte writes, a hat cleaner’s; the other a defunct burglar alarm company) had been painstakingly converted into a single space for youth programming, artist residencies, and exhibitions.

The Vice Lords, created as a coalition of several gangs in 1958 by young men incarcerated in the St. Charles Youth Prison, reinvented themselves in the mid-1960s as the Conservative Vice Lords. A turning point came one night when the older gang members were approached by a younger member: “He told us he wanted to take about fifty fellows later that night to make a fall. We asked him why and who he wanted to fall on; had anyone misused him. His reply was we the older lords including the fellows who are in jail had made a name and they wanted to keep it alive.”13 Alarmed at their part in creating an image of violence that had become self-perpetuating—perhaps also anxious to shore up control—the older members decided to form CVL, Inc. They formed a relationship with David Dawley, who had come to Chicago as a Transcentury Corporation staffer to do a study on ghetto residents’ attitudes toward the provision of social services.14 With his Dartmouth training and his personal contacts, Dawley helped the CVL members make contact with businesses and foundations. As spokesman Bobby Gore puts it, the Vice Lords “poured [their] hearts out to them.”15 With Dawley’s help, the CVL submitted successful grant proposals to foundations, and these substantial funds enabled them to create several businesses. The West Side was in crisis; foundations and business owners and upstanding community members were taking a risk. But perhaps the alternative seemed a bigger risk. CVL received backing from the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, the retailers Sears and Carson Pirie Scott, and other businesses and individuals.

At its high point, CVL, Inc. ran a diner, ice cream parlors, and a clothing shop—the African Lion, supported by Sammy Davis, Jr.—and promoted neighborhood cleanup programs and helped build playgrounds. The simple idea was that by establishing opportunities for training and jobs for kids, the gang might prevent violence among younger members and promote economic self-reliance for the community, keeping the community’s money in the community. It was a bid for economic autonomy for the neighborhood; it was also an attempt to convert illicit forms of power to licit ones, and to maintain a presence within the neighborhood that would be associated with positive, and not negative, effects on the community.

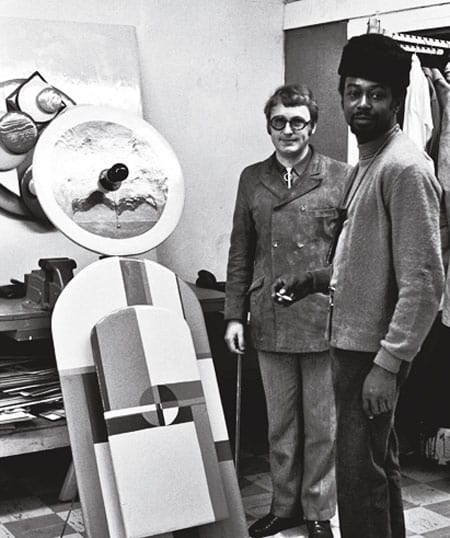

Jan van der Marck had arrived in Chicago in 1967 to direct the new Museum of Contemporary Art. He had originally traveled to the United States as a Rockefeller fellow to study American museums and their relationship to the public. First at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and then at the MCA, he started to put his ideas into practice. In early 1968 he met Zelle in New Orleans at the American Association of Museums meeting. He offered her a job, and she quickly packed up and moved to Chicago from New Jersey, where she had just finished an internship at the Newark Museum. The first written record of Art & Soul appears in the MCA timesheet, a set of ongoing records kept by van der Marck and Zelle. This meeting, held in May 1968, was itself the result of previous conversations. The record reads: “Meeting with Robert Stepto, Bernard Rogers, Allen Wardwell, Jan van der Marck to discuss what can be done in the way of art for the black community on the West Side. This meeting was prompted by previous discussions with Bernard Rogers, who for some time has been active with the Conservative Vice Lords, Inc., as well as by the Annual Museum Meeting in New Orleans where a session was devoted to the subject ‘How can museums be made more useful.’”16 It was a high-powered meeting. Wardwell was the head of what was at the time called the Primitive Art Department at the Art Institute of Chicago. Stepto was a trustee of the MCA, an African American physician who was a faculty member at the University of Chicago Medical School. He had taken an interest in the West Side since serving as head of the obstetrics and gynecology department at Cook County Hospital.17 Rogers was an insurance executive and a member of the Art Institute’s board of trustees. Early consultations also included David Dawley and the two Hetherington brothers. Daniel Hetherington was an especially talented artist; Jackie Hetherington had graduated from Crane Tech and Crane Junior College (later to become Malcolm X College), and had worked in a barber shop and in the display department at Compton’s Encyclopedia. He also had experience working on another CVL venture, Teen Town.18

The notes from an August meeting reveal further development of the project:

An art workshop-gallery, located in a remodeled store or several adjacent stores in an accessible area would be a center for all the arts from painting to sculpture to films and music, a place to work and a place in which to display, a meeting point for discussion and exposure to art. The center would be run by a neighborhood manager for the people of the neighborhood, and the role of the museum would be to provide ideas, counsel, contacts and technical advice.19

From the beginning, therefore, the museum saw its job as facilitation: it wasn’t setting up a branch location, or dispensing charity. On July 8, van der Marck approached Ralph Newman of the Illinois Sesquicentennial Commission, the organization set up to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Illinois statehood.20 Van der Marck hoped Newman would fund the project. Originally, van der Marck had proposed something quite different to the Sesquicentennial: Hydroscape, a floating sculpture garden on Lake Michigan, which would (according to van der Marck’s original proposal) have included works by a welter of famous names: Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint-Phalle, Christo, Yayoi Kusama, Les Levine, Francois Dallegret, Tony Smith, Robert Morris, Robert Smithson, Hans Haacke, Billy Apple, and others.21 Newman had been interested in this project, but it hadn’t panned out, apparently for lack of funds on the MCA’s side. Van der Marck would later say that “it turned out to be a sad case of my eyes being bigger than my stomach and trustees escorted me back from Delaware Riviera to Ontario Street.”22

When he heard of what was originally called the West Side Project, Newman also expressed immediate interest. He had funds available and was eager to enhance the representation of black Illinoisans in the Sesquicentennial festivities. But Newman was unwilling to use state funds to finance an operation run exclusively by a street gang, and emphasized that the project must involve other community partners and serve the community as a whole. Therefore, many different community groups were invited to initial meetings from which the advisory council developed. Community organizations that sent representatives or offered moral support of one kind or another included the Lawndale Youth Commission, West Side Federation, Lawndale Urban Progress Center, Better Boys Foundation, Boys Brotherhood Republic, the Lawndale People’s Planning Conference, the A.B.C. Youth Center, the Chicago Public Library, and the Catholic Church—a very different list from the first Sesquicentennial proposal van der Marck had drawn up.

Early meetings with community members were not overwhelmingly promising. Two women from Concerned Parents criticized the use of storefronts: van der Marck noted, “The point was driven home rather sharply that black people associate storefronts with churches, neighborhood clubs and in general poorly financed, faltering operations.” He went on to remark that “neither of the 2 ladies were thinking of the museum in terms other than the traditional concept.” While he saw promise in experiment, the women imagined something like the Art Institute; storefronts, they thought, would consign the operation to being a poor substitute for a real museum. They also objected to the use of funds for art at all—as opposed to more basic needs. As van der Marck reported in the timesheet, they asked, “Why do you white people all want to make your mark in the Lawndale area? Is that the way you want to get into the news?”22

The mothers’ doubts about gang involvement were shared by Lew Kreinberg of the Westside Federation, who proposed a location, a vacant bank building, outside the CVL’s territory. Van der Marck was excited by the scale of the building, as well as that of a vacant Oldsmobile dealership proposed by a development company, Greenleigh Associates. But these ideas quietly died—perhaps because they were too expensive or, in the case of the bank building, because it would have been difficult to get the project off the ground without the CVL. Van der Marck’s introduction to the concept had come through Rogers, who was the linchpin between Lawndale and the white cultural institutions downtown, and who had formed a specific connection with the CVL. Perhaps more important, the various social services and funding organizations had to reckon with the Vice Lords because they held the power in Lawndale. The CVL had the capacity to make things happen in a way that other organizations couldn’t.

That neighborhood programs required Vice Lord support is well illustrated by the experiences of architects who came there to build playgrounds for the Chicago Committee on Urban Opportunity’s Model Cities Programs. Raymond Broady, an African American architect who would provide the initial designs for Art & Soul’s building, first came back to the neighborhood he’d grown up in to work with the CCUO. As a young, recently licensed architect, having grown bored with his job with the General Services Administration, he moved to the job in Lawndale as the third architect-in-residence brought in within the space of a year to build vest-pocket parks along Sixteenth Street. The first man hired had been white; the second had been black; but neither was able to connect with the Vice Lords to get their support. Whenever they built a playground, kids would trash it the next day.

Broady had grown up on the West Side too, and was lucky enough to have gone to high school with Bobby Gore, one of the leaders of the CVL and a driving force behind the organization’s new approach to community involvement. Back then he had had Gore’s respect as a younger, studious kid with a shot at professional success outside the ghetto. When he returned to the neighborhood Gore helped smooth the transition with the younger Lords. With this “umbrella,” Broady asked if he could collaborate with the kids in the neighborhood to figure out what they could do to avoid having the playgrounds trashed.

“You’re just going to build whatever you want to build.”

“No, you tell us what you want, and that’s what we’ll build.”

“You’ll bring white guys in to build it.”

“No, the kids will get to build it themselves.”

“But they’ll have white foremen.”

“No, we’ll teach older Vice Lords all they need to know to be able to supervise the work themselves.”24

With this more collaborative approach and the support of the gang organization, Broady was able to proceed in his work.

But if the Vice Lords were needed to make the West Side Project go forward, they could not be the official recipients of Sesquicentennial funds. Newman made this clear. It had been a real priority for him to ensure African American representation in the Sesquicentennial events, and he was enthusiastic about the project in general, but he was wary of Vice Lord involvement. In a meeting at which the project seemed to be at an impasse, Newman proposed that, rather than disbursing funds to the project directly, the Sesquicentennial would hire an administrator who would have control over payments.25

This is how James Houlihan came into the picture. Later to become the Cook County Assessor, he was the Sesquicentennial Commission’s representative to Art & Soul. His role set him up for conflicts. He was there to ensure broader community participation and to keep control over the Sesquicentennial’s funds. As it was described in the August 12 meeting in which Newman proposed the administrator position, in addition to managing the budget, his role was to act “as a go-between among the Commission, the project, and the various elements of the community hopefully broadening community interest and support of the project.”26 Newman saw Houlihan’s position as a way to maintain limits on how much the project would belong to the Vice Lords. By contrast, Zelle defended their role. Both believed in community leadership of the project, but different definitions of community were at work. To Newman, the Vice Lords were a potentially nettlesome segment of the community; to Zelle, the Vice Lords—with their particular representatives, the Hetherington brothers—were the community with which the MCA was partnering. In notes in the timesheet she describes telling Jackie that she would defend his role as director of Art & Soul.27 Yet the requirement of a board drawn from different sectors of the community was, she says, a positive thing: “Art & Soul helped integrate the CVL into their community.”28

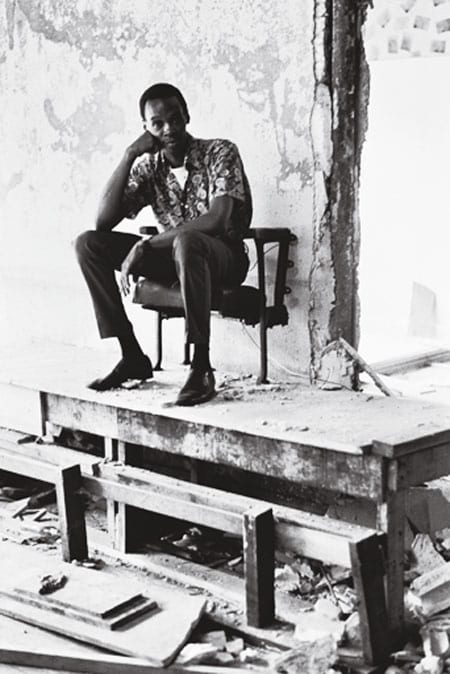

But a certain tension was indeed implicit in the institutional relationships. At times Houlihan and Jackie Hetherington found themselves at odds. The routine conflicts are illuminating. In one example, according to Houlihan, Jackie Hetherington asked to bill the Sesquicentennial for expenses that included Ripple, a (mildly) fortified wine produced by the Gallo winery that was popular at the time in the ghetto. As Houlihan put it, “He would say ‘Those executives downtown have their three martini lunches and put it on their expense accounts. Why can’t I have Ripple [and put it down as an expense]?’ I said, ‘Your logic is impeccable, but I’m still not going to do it.’” The interaction was jocular, but suggests how philanthropy with strings attached might rankle. A bigger issue in the use of funds was a conflict between spending on building renovation and spending on programs. As the head of the Sesquicentennial, a program of events commemorating Illinois’s 150th year of statehood, Newman obviously wanted the project to bear fruit—specifically through programming that could be reported to state government—in the year 1968. The project only got off the ground in the summer; spending too much time on renovations would slow the progress of the opening, and spending too much money would reduce program possibilities. Yet community members wanted to establish some permanence. Jackie Hetherington pushed for more extensive renovations. Once Broady saw the condition of the building, his cost estimates went up. The crumbling interior walls could not be redone without spending more money than Newman would allow. The questions of cost were emotionally and politically charged; recall the two mothers and their concerns about a storefront. If white money was coming into the neighborhood to build something, why couldn’t it be something magnificent? In a meeting on September 30, van der Marck, Zelle, and Rogers came to “agree with Jackie that enough money had to be spent to get the job done well and quickly.”29 The next day van der Marck expressed frustration: “Where are we? No payrolls yet. Everything is done piecemeal and nothing is done properly. . . . Forget preliminary budget—do remodeling right with black architect and contractor.”30 As Houlihan remembered it, Zelle had the idea to tack burlap over some of the interior walls and nail down a simple wood border rather than completely replacing the decayed plaster.31 This had the added benefit of providing a good surface for hanging artwork. The written records don’t provide a clear final answer to questions about the renovation costs, but within a month the space was nearly ready to open; a pre-opening Halloween party was held and Zelle noted with relief that the CVL had come through with support for the event, that it was a “good introduction to Art & Soul as an active, swinging place.”32 Two weeks later, it formally opened.

The Soul of Art

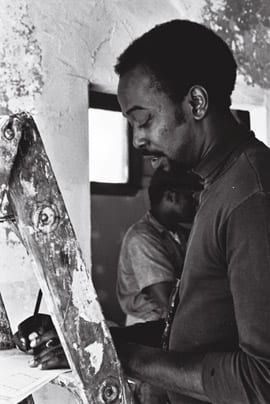

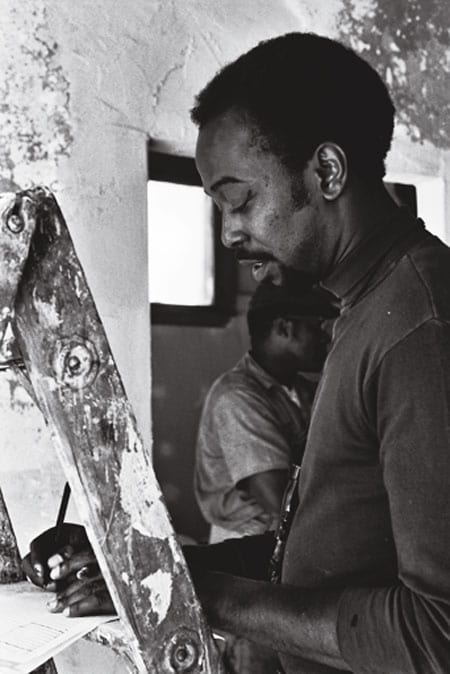

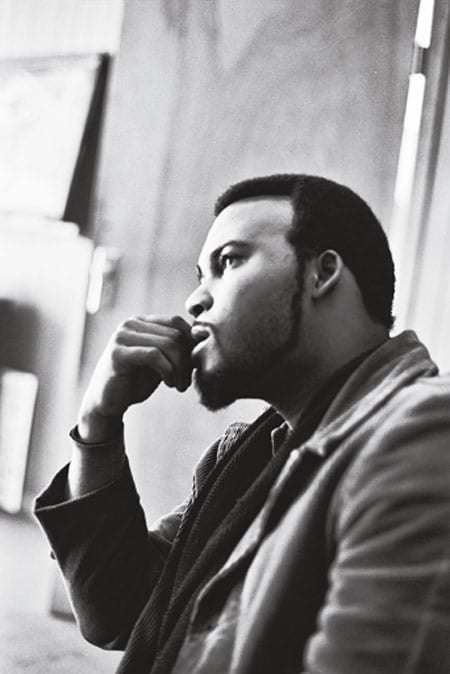

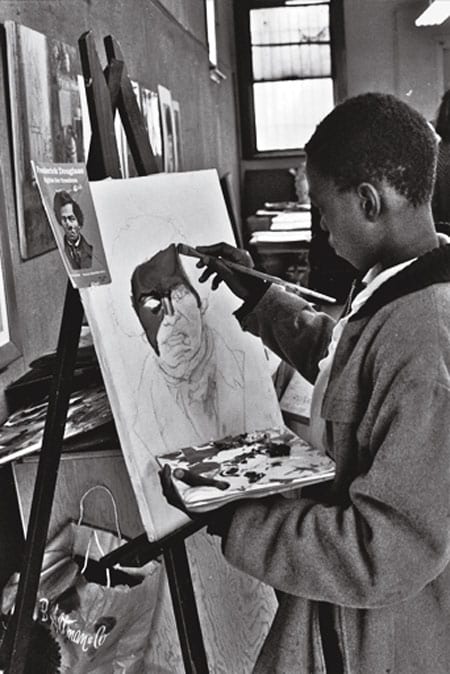

If anything, these tensions seem to have injected energy into the project. Eventually the collaborators became, as Houlihan put it, “trusted partners.” Although he recalls the project as misguided in certain ways, he also describes it as “a wonderful event.”33 Zelle echoes this sentiment: it was “very positive and fun. People were excited and interested. Lots of neighborhood people would come by. It was exhilarating and full of hope. Such a rich, productive, creative time.”34 Early on, Art & Soul hosted Ralph Arnold as artist-in-residence, displaying his collage paintings on its walls. The center held an art contest in which Jeff Donaldson of AFRICOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists, a group founded in 1968 by former members of the OBAC Visual Art Workshop) won first prize, and Peter Gilbert, a local sculptor who had been involved from the start and whose medium was animal bones, was second. Reggie Madison, who appears in several of Zelle’s photos touching up one of his entries at the last minute, won third place with an abstract kinetic sculpture he titled Black Madonna and Child. Art & Soul also hosted a traveling exhibition of African sculpture from the Art Institute’s collections. Staff offered classes in papier-mâché, puppets, and screenprinting; the center also held informal studio hours, and sponsored visits to the MCA and a poetry reading there by black poets (Eugene Perkins, Sigmonde Wimberli, and Ebon).35 The photographer Roy Lewis created an experimental installation of his photographs on the outer wall of the building, joining with other black photographers in Chicago—Bobby Sengstacke and Bob Crawford—who were inspired by the Wall of Respect on Chicago’s South Side to create their own form of mural. These photographic street museums could also serve as political rallying points.36 Lewis gave his installation the title West Wall with the subheading Proud of Being Black.37 It was documented in a booklet of poems entitled West Wall by Eugene Perkins. West Wall was a doubly meaningful title: it was the west wall of the building and also a wall of images for the West Side, as opposed to the South Side locations of Crawford and Sengstacke’s projects.38 West Wall: Proud of Being Black appears in Zelle’s photograph against the backdrop of rainbow stripes painted under the direction of the Japanese artist Sachio Yamashita, newly arrived from art school in Tokyo. His rainbow stripes, a signature of his work in the late 1960s and early 1970s, adorn Zelle’s color image of the storefronts.39

Funds from the Sesquicentennial ran out at the end of 1968, and fundraising efforts occupied much of the next six months. By the summer, most of the original staff had moved on. The details of the transition remain unclear, but from mid-1969 youth programs continued with federal funds administered by the University of Illinois at Chicago. The black mural artist Don McIlvaine, who was not a Vice Lord, took over as director and worked with children to paint powerful, aggressive, insistent murals throughout Lawndale. (His substantial oeuvre has now, tragically, been almost entirely demolished.) The project seems to have continued in a more limited way until 1972, when it was likely the victim of President Nixon’s dismantling of the Johnson-era Office of Economic Opportunity.40

Interviewed in late 1968 by Steven Pratt of the Chicago Tribune, Houlihan said that the work done by “artists here is a different type of art than that you see hanging in the north side galleries. That’s why the museum is so interested.”41 In shifting his attention from a project like the proposed Hydroscape to the West Side project that was to become Art & Soul, van der Marck had not abandoned the world of contemporary art as it was then understood. The language contained in a February 1969 funding proposal written was carefully modulated to draw on the rhetoric of contemporary art: “‘Art & Soul’ began as a six-month art happening in Lawndale, an experimental friendship between a street group and a museum.” The project was often described as a Happening and was directly inspired by the free stores of the Diggers, a San Francisco radical street theater group.42 Along with its commitment to children’s programming, Art & Soul was a way to be involved in the creation of new forms of art through dialogue between the contemporary white art world and the styles and concerns of black artists. The proposal also suggested that part of the project’s innovation was its responsiveness to African American cultural forms: “By providing the opportunity for the application of contemporary art techniques to black moods, the concept of ‘Art & Soul’ becomes a medium for new forms and styles in art.”43 “Black moods” was an interesting word choice. Other CVL grant proposals refer to overwhelming hopelessness as the “mood” of Lawndale, but here “black moods” seems instead to represent a more expansive and creative feeling. It also suggests the idea of creating, or maintaining, a distinctively African American style of art, something that Jackie Hetherington, too, emphasized in conversations with Zelle. An exhibition of African art was offered by the Art Institute, but Hetherington hesitated to stress African art at the expense of developing contemporary African American artists.44 He also rejected the MCA’s offer of Red Grooms’s Chicago billboard, which contained a caricatured African American boy.45

Van der Marck and Zelle, both relative newcomers to Chicago, had entered into a moment of political ferment that was also a moment of intense artistic ferment among African American artists in Chicago. The notion of a “Black Aesthetic” was being vigorously discussed and debated within the African American arts community of the period, much of it in the pages of Negro Digest (which changed its name to Black World in 1970), published in Chicago and edited by Hoyt Fuller.46 Black artists and writers voiced multiple and sometimes conflicting views on the importance of art and the specific aesthetic qualities it should possess, but one of the primary points was the insistence that art be connected to life: that art play a social and political role, that it be in the streets and among “the people.”47 This entailed a revolt against prevailing (white) institutional standards for art in which abstraction was still dominant. As James C. Hall has written, not only did “African-American art in the 1960s [claim] for itself an expansive social capacity” but the challenges it posed to modernist criticism “have been too often ignored as rhetorical or ceremonial.”48 Hall is speaking largely about literature, but his critique holds true for art history and criticism as well. The point was not a turn from art to a purely political form of blackness, but a redefinition of the relationship between art and politics accompanied by a sustained critique of the collusion of notions of aesthetic autonomy and universalism with racist ideologies.

Black artists had experienced—and generated—a powerful public confrontation between the white art world and their own ambitions when, in August 1967, artists on the South Side of Chicago created the Wall of Respect mural in response to the unveiling of the “Chicago Picasso.” One of the biggest mainstream public art events in Chicago in the 1960s was the arrival of Pablo Picasso’s monumental, untitled public sculpture in downtown Chicago. The African American poet Gwendolyn Brooks was commissioned to pronounce a poetic dedication at the opening. She began: “Does man love Art? Man visits Art, but squirms. Art hurts.”49 Brooks articulates a set of modernist aspirations for a kind of art that challenges its viewers. By the end of her dedicatory poem the Picasso is tamed: the hurt has changed its character, and the sculpture is no longer aggressive, but mutely autistic. She concludes: “Observe the tall cold of a Flower/which is as innocent and as guilty,/as meaningful and as meaningless as any/other flower in the western field.” Here, art is not so much challenging as standoffish; one views it clinically (“Observe”). “The western field,” on one level the American West, here is the Midwest; the western field is the prairie, and the hard art is naturalized, becomes part of the landscape. But the western field is also Western civilization, a field of flowers—and this bloom of COR-TEN steel—that are both “meaningful and meaningless.”

The respectful but ironic feeling contrasts sharply with her poem for the Wall of Respect, the collectively created mural completed at Forty-third Street and Langley Avenue just twelve days later.50 The juxtaposition was obvious: Don L. Lee, a younger black poet later to take the name Haki Madhubuti, wrote in his own poem about the wall that “Picasso ain’t got shit on us, send him back to art school.”51 Eugene Perkins—who, as director of the Better Boys Foundation, was to be a member of the advisory council of Art & Soul—wrote

Let Picasso’s enigma of steel

fester in the backyard of the

city fathers’ cretaceous sanctuary

It has no meaning for black people,

only showmanism to entertain

imbecilic critics who judge all art by

European standards . . .

The WALL is for black people . . .52

The Wall of Respect was painted by the Visual Art Workshop of OBAC, formed in May of 1967. It was everything the Picasso was not: it was avowedly made by Chicago artists in Chicago; it was the product of overt collaboration; it was done without the consent of the owner of the building, hence more or less destined for destruction and entirely without monetary value; and it had a political goal—to create a form of public art that represented black heroes and heroines.

To the US government, it was (according to witnesses) controversial enough that government snipers were positioned on surrounding rooftops at the opening ceremony.53 It was a major intervention into an urban visual culture that at the time had precious few representations of African American faces. To Lee, the government’s view was, in a sense, not incorrect: for him the wall was “a weapon.” He writes that “whi-te people . . . run from the mighty black wall”; it “kill[s] their eyes.”54

Brooks’s rhetoric about the Wall of Respect is not as aggressive as Lee’s or Perkins’s. But contrast it with the meaningful/meaningless “flower in the western field.” For this dedication, she ends with these words:

No child has defiled

the Heroes of this Wall this serious Appointment

this still Wing

this Scald this flute this heavy Light this Hinge.

An emphasis is paroled.

The old decapitations are revised,

the dispossessions beakless.

And we sing.

Brooks points to the fact that the wall had not been “defiled” with graffiti—a mark of its approval in the community. The wall is not a simple thing, but a “still Wing” and a “heavy Light.” It is both “Scald”—a sudden, violent image—and “flute”—a delicate flicker of sound. Its doubleness, strong and beautiful, and its presentness—its position between past and future—make it a “Hinge.” The wall is all these things—the paratactic succession of nouns articulated by the repetition of “this” also suggests the visual composition of the wall as a series of portraits that made up a collectivity. Taken as a whole, the wall is a bulwark against historical trauma, and a new form of history.

I linger over Brooks’s dedications to help establish the fact that a significant critical consciousness surrounded works like the Wall of Respect; that it was attuned to tensions between the demands of art and politics; and that it also consciously responded to the white mainstream art world and white critics. The late 1960s and early 1970s were a period of tireless publishing by presses like Detroit’s Broadside Press and Chicago’s Third World Press, as well as magazines like Negro Digest/Black World. Much of the best writing on black visual arts in this period was done by visual artists and poets. (Donaldson wrote that AFRICOBRA created “art for people and not for [white] critics whose peopleness is questionable.”)55 For example, the poet Carolyn Rodgers addresses all the arts in her essay “Feelings Are Sense: The Literature of Black.” Switching back and forth between prose and poetry, she writes of painting:

…Colors are to be used freely.

going against all techniques that are european. all colors

go on canvas together or rather create new families of colors

define what color is the body of a Black man must be viewed

beneath or beyond oppression . . .56

Rodgers’s words do what she asks colors to do, going together and creating “new families”—sentences that form backward and forward, meanings that work more than one way in her unpunctuated lines. Her phrase “define what color is the body of a Black man” doesn’t merely ask what color a black man’s body is, but defines color as the body of a black man.57

the canvas must be viewed as something

other than what european art dictates. Perhaps the canvas

itself is european

and needs to be thrown away.

Rodgers brings out the conceptual rhyme between color painted on canvas and the color of skin. She also identifies, from a different point of view, the Westernness of the easel picture acknowledged by Greenberg. She doesn’t ask black artists to stop painting, but to paint differently. Shifting from painting to sculpture, she also shifts seamlessly between maker and object:

paint on anything everything. the hands the fingers

of the sculptor are the many tongues

the fingers and what they make must become

the man, Black.

With the word “become,” she suggests the sense “to be becoming” in the sense of flattering, appropriate, beautiful. The sculpture made by the hands-fingers-tongues must be suitable: black art for black people. But it also suggests transformation, an act of making an artwork that is also the act of making a man. Addison Gayle writes in his introduction to The Black Aesthetic (1971) that, in contrast to white academic literary criticism and its various schools, black critics should evaluate works “in terms of the transformation . . . that the work of art demands from its audience.” He asks, “How far has the work gone in transforming an American Negro into an African-American or black man?”58 The work of art of the Black Arts Movement is not just the object; it is the person. The Wall of Respect was a beautiful thing. But it might not be so impressive if it were not for all the work that surrounded it. We must have a sufficiently capacious framing of the project to encompass not only the painting but also the planning and community negotiation and physical courage that it took to carry it out, and the performances, readings, music, and other events through which it temporarily transformed public space, and the project of remaking consciousness, of remaking people, that such projects undertook. This kind of frame is the best one for understanding Art & Soul.

Other Idleness

In May 1969, when Art & Soul had been open for six months, the Cook County State’s Attorney, Edward Hanrahan, along with Mayor Richard J. Daley, declared a “War on Gangs.” Together, they argued: “Gang claims that they are traditional boys’ clubs or community organizations ignore the violence and destruction of social values in the neighborhoods they terrorize.”59 Leaders of the CVL were harassed, arrested, and imprisoned, often with obviously flawed or manipulated judicial processes. And at the indictment of Bobby Gore, one of the Vice Lord leaders, on murder charges that many argued at the time and since were trumped up, Hanrahan pointedly excoriated granting organizations for giving money to gangs: “We think these brutal acts should cause foundations and others to intensify their scrutiny of persons seeking money from them to make certain their funds are not used to arm street gangsters or for other idleness.”60 Why was this war declared? Did Daley and Hanrahan not see the potential the “reformed” gangs offered? Several observers at the time, and historians more recently, have suggested that Daley saw their potential all too well. He knew this from personal experience. As a young leader of the Hamburg Athletic Association, he was a probable participant in the major race riot of 1919 in Chicago; throughout his life he refused to answer questions about his involvement.61 He knew exactly what could happen when gangs began to legitimize themselves and claim political power, because he had lived through this very experience. By this reading, the Conservative Vice Lords were not the exception to the rule, a force for good unfortunately swept up in an overly indiscriminate but ultimately necessary police operation provoked by the violence of other gangs. They were the provocation.

Hanrahan’s choice of words is quite striking. What did he mean by idleness—worthlessness, folly, inactivity; the nonfunctional, the nonproductive, the trivial, the fantastical? Did he mean, specifically, crime? Daley and Hanrahan made it clear that the funding offered by foundations was itself part of the provocation to the authorities. “Idleness” seems to roll off the tongue here as a general term for bad things: no matter what, the money is used for purposes not intended by the foundations.

On the other hand, from the point of view of dumbfounded Chicagoans who watched the erection of the Picasso in 1967 and wondered if it was a baboon, it might be art itself that constituted “idleness.” In a way, this isn’t so far from the art world’s own critical discourses. Idleness might be a beneficial condition, when it is understood as freedom from compulsion, or the ability of the imagination to roam. Children making papier-mâché masks in an open-ended art class might, too, be perceived to be idle. For Greenberg in his 1959 essay “The Case for Abstract Art,” the virtue of abstract art is that it encourages a meditative form of viewing. He argues that this is necessitated particularly in America as antidote to society’s devotion to profit-making, goal-oriented, instrumental activity (otherwise known as capitalism).62 By this definition, art as idleness—in its Kantian nonpurposive purposiveness—might indeed be salutary.

Yet if an “idle” form of art may be an antidote to profit-making, goal-oriented, instrumental activity, it is less clear how it could be an antidote to the situation of enforced idleness found in Lawndale, where the unemployment rate was three times the city average (and where the youth unemployment rate was 25 to 50 percent).63 This situation expresses a fundamental divide for modern art in its impulses toward reduction, asceticism, and negation. Where these modernist operations of self-sacrifice require a self to be sacrificed—they require self-possession—black artists were, and needed to be, engaged in a process of self-creation. At the same time, the necessity of construction and creation (that is, affirmative rather than negative operations) transcended race. When artists joined in the Richard J. Daley exhibition at the Feigen Gallery to protest the police attacks on protesters at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, Robert Motherwell sent two already completed canvases that were, he stated, without political content. “There is a certain kind of art which I belong to. It can no more make a direct political comment than chamber music can.”64 But the problematic status of this position, in 1968, is palpable, for he also glossed this parti pris a bit by suggesting that context made the works political: “The significance is to participate,” he said, and elsewhere, “This show represents the politics of feeling, not the politics of ideology.”65 It might be argued that perhaps the gesture itself—the participation, as performance—was part of the art. The art, as well as “the [political] significance,” was to participate—not to stand idly by.

Today, postindustrial shifts in national and global economies to a situation characterized by unemployment and precarity might prompt us to redirect our ideas not only about how art engages with social and political issues but also how it engages with work.66 Indeed, what kind of “work” can count as the “work” of art? There were art objects made and displayed at Art & Soul. In a way, though, these objects were only the documents of the real work: the building, cleaning, organizing, educating, befriending, negotiating, managing, risk-taking, material gathering, directing, grant-writing, learning, dreaming, schmoozing, protecting, collaborating, remembering, and contributing of cultural knowledge. Many of these tasks would in the coming years be signaled as art and not just adjuncts to it—by Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Andrea Fraser, and others.67 During this historical period artists and critics began to view the avant-garde as co-opted by capitalism, and a range of practices (performance, feminism, conceptualism) began, in various ways, to challenge modernist assumptions and to herald what would be called postmodernism. As Julia Bryan-Wilson deftly shows in Art Workers, the Art Workers Coalition’s 1970 Art Strike presents a tension between the desire to recast art as labor, in a gesture of working-class solidarity—and the impulse of refusal, the withdrawal of meaning-making activity, that is both an attempt at political statement and an unintentional rhyme with quietist tropes of mid-century American modernism.

Art & Soul was a bargain struck between two groups—each individually comprising complex interests—that knew, at the outset, very little about one another. For their own separate reasons, each agreed to construct this space both to foster creativity in Lawndale from the ground up and to celebrate African American art and artists in Chicago. If the creation of subjectivity and consciousness were “the work of art”—the productive activity of art—and not just effects of artworks, this means the art itself may be difficult to fasten in our sights, but it also may make this a historical reference point that can reciprocally frame and be framed by later projects such as Havana’s Arte de Conducta.

“And we sing.” Art & Soul was not a black revolutionary project like the Wall of Respect. It was a pragmatic bargain among organizations with rather different interests. It borrowed, and was sometimes a vehicle for, the Black Arts Movement’s aspirations, and in making do with limited resources and challenging presuppositions, it also made an art of the labor required to create such a space. One cannot claim any precedence for Art & Soul in relation to the South Side collective black projects (Wall of Respect, OBAC and AFRICOBRA, the Museum of African History, the Affro-Arts Theatre). These groups and projects deserve much more attention in their own right, as part of the history of art of the twentieth century. What is most important about Art & Soul is the remarkable fact of the engagement of the MCA and other white institutions, in an aesthetic project, with a street gang, whose members engaged in the project as essential partners and not merely recipients of charity. The multiple kinds of labor that went into allowing this risky, fragile experiment to happen even for a short time express the content of the project as need, crisis, poverty, danger, and power—as well as optimism and creativity. “Other idleness”: next to “arming street gangsters” it sounds like an understatement. But then, it is a capacious phrase. It could mean violence, it could mean loitering. It could mean art. If the reported presence of FBI snipers at the unveiling of the Wall of Respect in Chicago in 1967 is any indication, some of the “authorities,” anyway, believed that black people making art was itself violence.

Both sides ran risks in engaging in the collaboration called Art & Soul, and some of those risks and their effects lie beyond the scope of this essay. From the point of view of the writing of art history, theory, and criticism, to write about elements of work that might seem mundane poses a smaller, but definite risk: the potential loss of the currency we hope to find in aesthetic exquisiteness. But perhaps we might lose it only to find it reinvented in another form. As an experimental friendship, Art & Soul can help us pose questions about the kinds of aesthetic and political risk we are or aren’t taking today.

Rebecca Zorach is associate professor of art history at the University of Chicago. Her book The Passionate Triangle was published by the University of Chicago Press in 2011. With Daniel Tucker, she is at work on Never the Same, an archive of interviews on transformative experiences in art. Her current research, from which this article is drawn, deals with African American artists, institutional experimentation, and the notion of the public in 1960s–70s Chicago.

Thanks are due to Laura Gluckman, who first made me aware of Art & Soul, and many others who have supported this research in a variety of ways: Theaster Gates, Orron Kenyetta, Mess Hall (Lora Lode in particular), the Radical Art Caucus of CAA (especially Alan Moore, Susan King Obarski, and members of the “Autonomizing Practices” panel), Greg Sholette, and Hannah Feldman. I also benefited greatly from conversations with Dan Wang, Rozalinda Borcila, and Mike Phillips, and I only wish I had been equal to the task of incorporating all of Darby English’s typically astute commentary and critique. Thanks also to the heroic work of research assistants Chris Brancaccio, Young Joon Kwak, and Kate Aguirre. Finally I am deeply grateful to Ann Zelle, Jerry Hetherington, Jim Houlihan, Bobby Gore, Ray Broady, Eileen Petersen Yamashita, Roy Lewis, Reggie Madison, Sam Yanari, and Corbett vs. Dempsey Gallery for taking the time to share stories and grant image permissions.

- Donald Mosby, “Westside Gang Plans Business Ventures” Chicago Daily Defender,April 4, 1968, 1. ↩

- Conservative Vice Lords, Inc., Proposal to Rockefeller Foundation (signed Alfonso Alford, to Joseph Black, Director, Humanities and Social Sciences), December 20, 1967, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, Record group: 01.0002, Series 200, Box 113, folder 997, 2. ↩

- In “Interventions Reviews,” Art Bulletin 88, no. 2 (June 2006), many reviewers make this and related points about problematic authorship of these two entries as well as the absence of political art and questions of race and ethnicity; see Nancy Troy (374), Geoffrey Batchen (376), Amelia Jones (377–79), Romy Golan (382), and Robert Storr (384–85). A note appears on the copyright page of Art since 1900 to credit the otherwise mysterious “AD” who authored the two entries: “The publishers would like to thank Amy Dempsey for her assistance in the preparation of the book.” ↩

- I use “white-supremacist” in the sense of pervasive and often unstated expectations of racial hierarchy, as in bell hooks’s usage in “Overcoming White Supremacy,” Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black (Boston: South End Press, 1989), 112–19. ↩

- See Julia Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009) ↩

- Clement Greenberg, “An Essay on Paul Klee,” Collected Essays and Criticism, ed. John O’Brian, vol. 3, Affirmations and Refusals, 1950–1956 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 5. ↩

- Charles Mills, The Racial Contract (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), 30. Later critics writing in Greenberg’s wake have insisted even more on the specificity of the medium and on evaluation by comparison with the (European) history of the medium. For Michael Fried, it is a “basic modernist tenet” that new paintings must “‘sustain comparison’ with older works whose quality is not in doubt.” Fried, “An Introduction to My Art Criticism,” in Art and Objecthood (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 1–74; 74, n81—a sentiment repeated several times in essays in the collection (38, 165, 169). The structure of beginning with certainty (or rather absence-of-doubt) recuperates time by mapping the Cartesian cogito onto history just as the “modernist reduction” maps it in space. ↩

- See for instance Peter Yates, “A Digression around the Subject, Unpopular Criticism is Necessary, or ‘Don’t Stop the World, I’m Still on It,’” Arts in Society 6, no. 1 (1969): 62–69; or Judith Adler, “‘Revolutionary’ Art and the ‘Art’ of Revolution: Aesthetic Work in a Millenarian Period,” Theory and Society 3 (Spring 1976): 417–35. ↩

- See for instance the now nearly forgotten journal Arts in Society published by the University of Wisconsin Extension Division from 1958 to 1976. ↩

- Claire Bishop, “Havana Diary: Arte de Conducta,” Untitled: A Review of Contemporary Art 45 (2008): 38–43, 41–42. ↩

- I am inspired in this research by Greg Sholette’s notion of the “dark matter” of the art world. Yet in this context in particular, the phrase makes me uneasy. He does not use it in a racially specific way, and yet it describes the invisibility of the Black Arts Movement all too well. Gregory Sholette, “Dark Matter: Activist Art and the Counter-public Sphere,” Journal of Aesthetics and Protest 1, no. 3 (2004): 13–24. On exclusions see also Francis Frascina, Art, Politics, and Dissent: Aspects of the Art Left in Sixties America (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1999). ↩

- Robert Nolte, “Artists Paint a Bright Spot on West Side,” Chicago Tribune,November 14, 1968, A4. ↩

- CVL, Inc. “A Unique Friendship between the Street and a Museum: Art & Soul,” grant proposal, 1969. Museum of Contemporary Art, Van der Marck papers, 13. ↩

- Dawley tells the story of the CVL in his book A Nation of Lords: The Autobiography of the Vice Lords (Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1973). ↩

- Bobby Gore interview, June 15, 2011. ↩

- MCA Art & Soul Timesheet, May 29, 1968. All references to the MCA Timesheet refer to a file kept by Ann Zelle and now filed with Jan van der Marck’s papers at the MCA in Chicago. ↩

- Personal communication, Robert Stepto, Jr. ↩

- MCA Timesheet, West Side Progress Report (Trustees’ Meeting), October 8, 1968. ↩

- “Meeting on Proposed West Side Art Project.” MCA Timesheet, August 12, 1968. ↩

- MCA Timesheet, July 8, 1968. ↩

- Chicago History Museum, Ralph Newman papers, Box 592/394A, Museum of Contemporary Art, June 1, 1967. ↩

- Meeting of Leadership Group at Sears YMCA. MCA Timesheet, August 8, 1968. ↩

- Meeting of Leadership Group at Sears YMCA. MCA Timesheet, August 8, 1968. ↩

- Raymond Broady interview, January 16, 2010. ↩

- “Meeting on Proposed West Side Art Project.” MCA Timesheet, August 12, 1968. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- MCA Timesheet, October 2, 1968. ↩

- Ann Zelle interview, November 24, 2010. ↩

- MCA Timesheet, September 30, 1968. ↩

- MCA Timesheet, October 1, 1968. ↩

- Houlihan interview, February 10, 2010. ↩

- MCA Timesheet, October 31, 1968. ↩

- Houlihan interview, February 10, 2010. ↩

- Zelle interview, November 24, 2010. ↩

- “An Evening of Black Poetry,” MCA news release, May 2, 1969. MCA, Van der Marck files. ↩

- Funding was provided to the South Side Community Art Center by the Illinois Arts Council, the Chicago Committee on Urban Opportunity, and the National Endowment for the Arts for three photographic murals. Bob Crawford’s was at the Umoja Black Student Center in the Oakland neighborhood, and Robert Sengstacke’s was in Englewood at Sixty-second and Halsted Streets. “New Walls for City,” Chicago Defender, October 22, 1968, 14–15. Roy Lewis’s mural also appears in Catalysts Cultural Committee, Black Cultural Directory Chicago ’69 (Chicago: Catalysts, 1969), 29. Crawford’s wall is visible in a photograph of the Umoja Center that accompanied an article on a student boycott in Jet: “Chicago Pupils Boycott; Board Member Agrees,” October 31, 1968, 28. ↩

- “New Walls for City,” Chicago Defender, October 22, 1968, 14–15. ↩

- Eugene Perkins and Roy Lewis, West Wall (Chicago: Free Black Press, 1968). ↩

- Sam Yanari interview, November 17, 2010. ↩

- See “Mcllvaine seeks 24th Ward Seat,” Chicago Defender, December 5, 1974, 4. ↩

- Steven Pratt, “Sesquicentennial Group Helps Gang to Open Art Gallery-Studio,” Chicago Tribune, November 7, 1968, W2. ↩

- Although the idea of a free bookstore—based on the Diggers’ free stores—had been nixed in an early meeting with area pastors, it resurfaced in the description of Art & Soul as “A Community Art/Book Center for All Ages” in its opening program. Program in van der Marck papers; Timesheet, July 10, 1968. ↩

- CVL, Inc. “A Unique Friendship between the Street and a Museum: Art & Soul,” grant proposal, 1969. MCA, Van der Marck papers. ↩

- MCA Timesheet, October 2, 1968. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- On the Black Arts Movement in Chicago, see an important essay by Margo Natalie Crawford, “Black Light on the Wall of Respect: The Chicago Black Arts Movement,” in New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement, ed. Lisa Gail Collins and Crawford (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006). The collection also contains an essay by Mary Ellen Lennon, “A Question of Relevancy: New York Museums and the Black Arts Movement,” that addresses issues in New York similar to those the present essay addresses for Chicago. ↩

- See for instance the essays collected in The Black Aesthetic, ed. Addison Gayle, Jr. (Garden City, NJ: Doubleday, 1971). ↩

- James C. Hall, Mercy Mercy Me: African-American Culture and the American Sixties (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 5. ↩

- Gwendolyn Brooks’s “The Chicago Picasso” and “The Wall” appear under the heading Two Dedications in the “After Mecca” section of Brooks, In the Mecca (New York: Harper and Row, 1968), 40-43. ↩

- The contrast between the two poems has been noted frequently. See William H. Hansell, “Aestheticism versus Political Militancy in Gwendolyn Brooks’s ‘The Chicago Picasso’ and ‘The Wall,’” CLA Journal 17, no. 1 (September 1973): 11–15; D. H. Melhem, Gwendolyn Brooks: Poetry and the Heroic Voice (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1987), 178–81; and Daniel Punday, “The Black Arts Movement and the Genealogy of Multimedia,” New Literary History 37, no. 4 (Autumn 2006): 777–94, 789–92. ↩

- Don L. Lee, “The Wall,” Black Pride (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1968), 26. A different version appeared in the Chicago Daily Defender, August 29, 1967, 14. ↩

- Eugene Perkins, “Black Culture,” Black Cultural Directory Chicago ’69, 12. ↩

- See Jeff Donaldson, “Africobra 1 (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) ‘10 in Search of a Nation,’” Black World (October 1970); and Barbara Jones-Hogu, personal communication. ↩

- Lee, 26. ↩

- Donaldson, 83. ↩

- Carolyn Rodgers, “Feelings Are Sense: The Literature of Black,” Black World, June 1970, 5–11, 11. Further citations are from the same page. ↩

- While in this essay she makes masculinist assumptions that obscure the place of African American women (and thus her own place) in the movement, elsewhere she critiques the gender ideology of black nationalist and revolutionary culture. ↩

- Gayle, introduction, The Black Aesthetic, xxii. Obviously, there are also questions of gender to be addressed here. ↩

- Hanrahan quoted in John Hagedorn, A World of Gangs: Armed Young Men and Gangsta Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 79. ↩

- Hanrahan quoted in “Boyle Defends Shamberg in Setting Bond,” Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1969, 9. ↩

- Hagedorn, A World of Gangs, 66–72. ↩

- Clement Greenberg, “The Case for Abstract Art,” Collected Essays and Criticism, ed. John O’Brian, vol. 4, Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957–1969 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 75–84, 82. ↩

- Beryl Satter, Family Properties: How the Struggle over Race and Real Estate Transformed Chicago and Urban America (New York: Henry Holt, 2010), 403, n101. ↩

- Motherwell quoted in “Artists vs. Mayor Daley,” Newsweek, November 4, 1968, 117, cited in Therese Schwartz, “The Politicalization of the Avant-Garde II,” Art in America 60, no. 2 (March–April 1972): 70–79, 71. ↩

- “The Politics of Feeling,” Time, November 1, 1968, online at www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,839608,00.html, accessed December 18, 2010. ↩

- Precarity, in both scholarly terminology and movement politics, refers to the normalization and extension of precarious employment prospects and economic conditions for a broad swath of society, from migrant workers to displaced office workers to contingent university faculty. There is an extensive literature on precarity (précarité) in French. See Nicolas Bourriaud, ed., Open 17: A Precarious Existence: Vulnerability in the Public Domain (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2009); and Stevphen Shukaitis,Imaginal Machines: Autonomy and Self-Organization in the Revolutions of Everyday Life (London: Minor Compositions, 2009). ↩

- See, for instance, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, “Maintenance Art Manifesto” (1969), inTheories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings, ed. Kristine Stiles and Peter Selz (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 622–24; and Andrea Fraser, “What’s Intangible, Transitory, Mediating, Participatory, and Rendered in the Public Sphere?” October 80 (Spring 1997): 111–16. ↩