From Art Journal 71, no. 1 (Spring 2012)

It’s not about the piece but about how the pieces fit together. It’s about taking something that already exists, and making something special.

—Ice Cube

A marketing triumph, Pacific Standard Time has been responsible for a series of promotional videos, slickly produced, that pair an honored artist with a Southern California celebrity. The shining success among these original works is the pairing of the late design team Ray and Charles Eames with the rapper and actor Ice Cube. The promo performatively enacts both the mainstream ambitions and the eccentric interests that play out in the larger scope of the Pacific Standard Time project. Important here, as in other locations throughout PST that will be explored in this essay, a politicized racial subjectivity signifies a kind of vanguardism that, in this time and place, can finally be aligned with avant-gardist art strategies. Featured prominently on the Getty Museum’s website, accompanied by Ice Cube posters on bus stops around Los Angeles, this promo is a touch more surprising than the museum’s de rigueur videos with John Baldassari and Ed Ruscha. The Eameses come off as Ice Cube’s California kindred spirits: like the rapper, they invented their own art forms and unique career paths. “Coming from South Central Los Angeles, you’ve got to use what you’ve got and make the best of it. What I love about the Eameses is how resourceful they are.”1 Shot in the gritty realness of black and white, the promo features Ice Cube giving a tour of quirky L.A. architectural landmarks from the driver’s seat of his convertible. “405 traffic: that’s bourgie traffic. 110 traffic: that’s gangsta traffic. There’s a difference.” Maintaining his attention to difference, the performer finally arrives at the famous Eames Case Study home, the star of the couple’s films such as House after Five Years’ Living (1955). Neither black nor poor, the Eames world was a long way from South Central. Nevertheless Ice Cube continues to draw parallels: “Before I did rap music, I studied architectural drafting. One thing I learned was, you’ve always gotta have a plan.” He compares the Eameses’ resourceful combinations of postwar prefabricated elements with the practice of sampling in hip-hop. Noting the house’s sensitive relationship to the land on which it’s situated, he declares to the camera: “This is going green 1949 style, bitch. Believe that.”

What does that mean, Ice Cube? A contemporary environmentalist slogan is set into an historic time which the Eameses were so obviously ahead of. The performer uses his celebrity authority and his hip-hop credibility to affirm the veracity of this distant fact. But who is the bitch? Me? The Getty? All of us? Is that a term of endearment or a sign of hostility? Are there misogynist or homophobic connotations? Why not just call us “niggas”? That would be too much, a transgression too far, and perhaps a less appropriate description of this audience. But have we come so far around that it’s not too much for a onetime gangsta rapper and former avowed enemy of the LAPD, working on behalf of a conservative institution and under corporate advertising direction, to call the museum public a bitch to its face? Is this postmodern multiplicity, under which minority dialects are brought into equivalence with standard speech, where black colloquial talk is validated as one of many permissible languages that communicates with a decentralized apparatus? Or is this that postmodern assimilative force that renders all speech, all difference, all performativity meaningless under the auspices of spectacular dominance? Does this practice of equivalence, a deeply democratic notion, strengthen different voices, or finally order them into a more manageable and compliant public sphere?

Like the region’s oft-cited assemblage tradition pioneered by artists like Betye Saar on one hand and Edward Kienholz on the other, Pacific Standard Time draws attention to differences in relation. It’s about how the pieces fit together. Ice Cube and the Eameses represent the dramatic restructuring set in motion by Pacific Standard Time, an initiative involving practically every art institution in the region. PST’s intention, laid out in the catalogue of the Getty Museum’s own exhibition, has been to reorient a history of American modernist art practices to reflect those innovations developed in Los Angeles. This primary purpose proposes a modest change to the standard Europe-to-New-York history, but that proposition has mobilized a proliferation of alternate histories, many of which reflect political motivations far more radical than the Getty’s own. Throughout Southern California, numerous PST exhibitions have featured formerly marginalized subjects, formerly marginalized mediums, or both, stretching modernist art premises in ways the Getty might not have initially imagined. As in the promotional video that pairs an idiosyncratic design collective with an innovator of West Coast hip-hop, the margins of the mainstream have come into specific focus through PST, and are building contextual relationships that distort the constructions of form, value, artistic practice, and aesthetic experience that have dominated modernist art ideologies.

PST’s different history has become a history of differences. While the Getty Museum’s own exhibition lays out objects associated with local finish-fetish trends and other refined formal projects of the post-mid-century, the city’s largest contemporary art exhibitors have been a touch more daring. The Hammer Museum has presented a scholarly attempt to set a record straight in Now Dig This! Black Art in Los Angeles, 1960–1980, organized by the art historian Kellie Jones. At the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), in addition to an already existing installation of films by Kenneth Anger, a queer icon, and a show of Hollywood photographs by Weegee, both of which exceed the fine-art category altogether, an extensive review of local contemporary artists has been presented in the curator Paul Schimmel’s Under the Big Black Sun: California Art 1974–1981, which jumbles together conceptualist, feminist, performance, and Pop art, as well as craft, political printmaking, murals, punk music, and photography practices, along with a handful of paintings, into a mélange of compelling and rewarding singular works. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presented a design show, which included the Eameses, but also two exhibitions with dense minoritarian vibrations: a retrospective of the performance collective Asco, and a long-hidden, room-size Kienholz installation, Five Car Stud (1969–72), that depicts the lynching of a black man.

Of course, these would be unlikely institutional occurrences during the years in question. One of the finest PST shows was Asco: Elite of the Obscure, 1972–1987, a survey of the group’s work organized by C. Ondine Chavoya and Rita Gonzalez. Though the collective’s members were engaged in visual art through other means as well, their collaborative work made in the 1970s was action-based, politically critical, and formally transgressive, helping to innovate a kind of performance art that has since endured. Within the group’s theatrical, cinematic oeuvre, one resonant image is Spray Paint LACMA (East Bridge) (1972), a photograph of Patssi Valdez posed against the museum building, situated above graffiti inscribed by Harry Gamboa, Jr., Gronk, and Willie Herrón. While she emphasizes the text with her body, Valdez also disregards it, glancing instead over her shoulder, perhaps nervously. The group had tagged the LACMA building the night before, performing its exclusion from the institution by suggesting that that would be the only way the Chicano, semi-queer collective would be able to show art there. Valdez suffered her own exclusion, prohibited by her male collaborators from joining them on their graffiti mission the night before.2

Instead, Valdez’s photographed body personifies the racial, gender, and political differences that played out against the body of the museum in this action, a museum that had a poor history of showing women artists, people of color, or performance art, even. Now, with a carefully curated exhibition, a gloriously thorough 432-page catalogue, and demonstrations of public appreciation that extended to the cover of the New York–based Artforum magazine, Asco has been reoriented.3 The Asco exhibition, which transforms provisional performances, videos, and ephemera into a legible museum display, reasserts the question that lingers around so many of these projects: is this a radicalization of the institution or an institutionalization of the radical? The answer to this question, here and elsewhere, is yes, both. That this question has more than one answer is already a signal that the singular force of the institution can be unsettled by ambivalent production. While such institutionalization softens the rough edges of marginal practices, it also deconsolidates the centralizing power that the institution promotes. While this back-and-forth may limit radical possibilities, it also activates the critical potential in works and practices that agitate against institutional structures. While the LACMA exhibition partially serves as a self-exonerating corrective to the exclusions invoked in the spray-paint act, it also consecrates a critical acknowledgment of that exclusion, installing a recognition of racist histories into the official discourse. The enterprise proves less radical than the group’s original street actions, more liberal than the exclusionary history of the institution. In a kind of dialectical synthesis, art history undergoes progress.

Even Five Car Stud, made by a prominent Los Angeles artist but not seen in L.A. at the time it was made, has shifted with the historical situation. Though Kienholz’s largest undertaking to that point, it was shown only at Documenta 5 and a few other German venues. Until recently, it has been in storage in Japan, sequestered because the elaborate installation is difficult to transport and mount, but also because of its confrontational subject matter. It had never been on view in the United States before this LACMA exhibition. The work consists of five old cars arranged in a circle in a dark room, their headlights illuminating a central scene of grotesque white men, realistically scaled but made of plaster and rubber, who are gathered around a somewhat abstracted black man who lies on the ground. As a couple of the figures hold the black man down, another is posed to slice off his penis with a knife. The black man’s torso is a small pool of fluid in which the letters N, I, G, G, E, and R float around with kinetic possibility. While the scene itself is disturbing, among the most eerie aspects of the experience are seeing one’s own footprints along with those of all of the other gallery visitors that are registered in the sand covering the floor, leaving traces of everyone who has visited and thus participated in the scene, and creating an overlap between this flurry of activity and that. Another uncanny phenomenon results from the way that viewers gather around the space and look in toward the lynching, replicating the positions and the gazes of the grotesque cast figures who watch from the periphery. For a moment, in one’s own peripheral vision, one can confuse the presence of a museum visitor who is standing still with the presence of one of the sculpted culprits. The immersive environment, the theatrical lighting, the installation’s various narrative suggestions, and the sense that these figures are posed mid-action—all enact a political drama that compels viewers to engage with the discursive terms of racial spectacle. The opposite of minimalist, Five Car Stud represents a specific cultural signifier at real scale, symbolizing a fundamental history of American racism.

Made during the years when Black Power had overcome Civil Rights, when urban riots and prominent assassinations had rephrased the history of spectacular violence against African Americans, Kienholz’s piece was perhaps too hot for American institutions and audiences of its own time. LACMA itself had experienced a controversy with the artist’s Back Seat Dodge ’38 (1964), which produced a public outcry on the grounds of its sexual representation (it was called “revolting, pornographic and blasphemous” by the powerful supervisory board that oversaw, among other things, the the museum itself).4 One can speculate that Five Car Stud would have caused a stir as well in Los Angeles, at a time when Black Panthers and the LAPD were engaged in a televised street war. While evoking the racial tensions of its time, the piece in its latest form also asks viewers to meditate on what’s changed since then. As the scholar Leigh Raiford writes in the exhibition brochure:

Edward Kienholz’s Five Car Stud (1969–1972) remains as powerful and disturbing, overwhelming and irritating, as it was when it first appeared in Germany. . . . In this interregnum, history continued to move, challenging and correcting the violent wrongs depicted in this piece. While Five Car Stud slept in its crates, we have witnessed the end of Jim Crow segregation and the extension of democracy to all US citizens, and we have celebrated the end of Apartheid in South Africa and the election of a mixed-race black man as president of the US. Yet in the same decades we have built the largest system of mass incarceration in history—with 2.3 million Americans behind bars, the majority of them black or brown (far more men of color than attend college)—and witnessed the rise of a race-baiting political party that questions Obama’s legitimacy as an American. Five Car Stud in its return to its country of origin at once transports us back to a time of unambiguous violence, hatred, and racial divisions, while alerting us to our own current crises.[Leigh Raiford, “Edward Kienholz: Five Car Stud 1969/2011,” in Edward Kienholz: Five Car Stud, 1969-1972, Revisited, exhibition brochure (LACMA, 2011).]

In introducing the work, Raiford begins by contextualizing the difference between then and now. Interestingly, the shift from lynching to prison seems to mirror an epistemological shift Michel Foucault outlined in European history, from punishment on the scaffold to the invisible institutional correction perfected in the panopticon. Important in Foucault’s Discipline and Punish is the idea that power transforms rather than abates.5 While the lynching itself feels anachronistic, the problem of racial antagonism does not. Five Car Stud, in its current iteration, at once tells a story of progress and of the enduring institutional structures around which this progress maneuvers. The Los Angeles Times critic Holly Myers introduced the return of the work with careful uncertainty: “How it will be received today—whether as a historical document of the civil rights era or as lens to turn on the darkest tendencies of our own time—remains to be seen.”6 Despite its explicit representation, we can now read the piece in multiple ways. The space between then and now is opened up in this dark room, unfolding in more than one direction, animated by ambivalent potential.

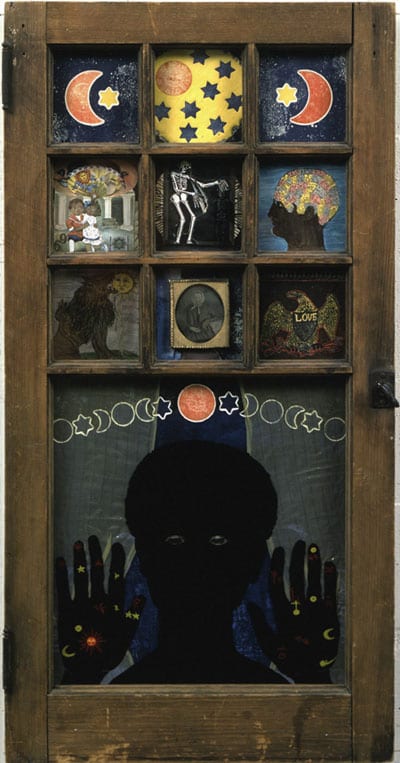

Five Car Stud, along with the gallery full of historicizing (apologizing?) wall texts that one passes on the way into the exhibition, reflects shifts in the discourse around difference that have taken place over these past decades. While representation is one problem raised in this discourse, participation has been another, as the Asco show demonstrates. The first African American artist to have a solo show at LACMA was Maren Hassinger, in 1981, a fact that helps point to the exclusions that characterize the pre-1980 period of PST.7 In an inversion of that negativity, the Hammer Museum’s Now Dig This! uses the PST structure to transform a set of historically marginalized artists into a major museum presence. Artists like Hassinger, who was commissioned by the Hammer to reconstruct a few large-scale wire sculptures, appear here, deservedly, in the corrective embrace of museum consecration. An important scholarly inscription in the art-historical record, the exhibition and catalogue connect a few well-known figures (Saar, John Outterbridge, David Hammonds) to an incredibly dynamic and productive art scene that at the time was “lacking representation in mainstream institutions,” as Jones describes it.8 While most of the artists participated with official art culture on some level, through art schools or professional careers, most also worked beyond mainstream institutions and invented their own ways of showing art that would resonate with their African American experiences. Presented here in a series of thematic groupings, the erudite exhibition reveals practices in dialogue and collaboration, originating in self-run galleries and aided by communitarian friendships, demonstrating the best of the L.A. art spirit.

One of these friendships was made evident in the opening weekend’s performance by Hassinger, Ulysses Jenkins, and Senga Nengudi. Reviving some elements of previous performance projects such as Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978), which was designed by Nengudi using her signature pantyhose constructions and first performed under an L.A. freeway overpass by Nengudi, Hassinger, Jenkins, Hammonds, and others, this reunion appearance brought some of the ritualistic elements devised in those early performances into a multipurpose space inside the museum. The writer Nick Stillman describes Nengudi’s recollection of the former public site: “Nengudi says she was drawn to that unexceptional patch of public land because the modest natural life persisting there⎯tiny palms and shrubs amid the dirt ⎯ ‘had the sense of Africa.’”9 While the Hammer’s annex certainly does not offer a sense of Africa, the three artists reconvened there wearing pantyhose fetishes on their heads and bodies, and arranged within a space delineated by Hassinger’s wire constructions, as a large audience of museum visitors gathered. In this simple act, a kind of convocation, the three artists distributed candles under projected starlight, kissed the cheeks of audience members, and offered the instruction that people should hug themselves, while they gently sang “This Little Light of Mine.” Soon the whole room was quietly singing. This modest ritual, performed by artists who are over sixty, signaled a kind of calm vindication. Despite the campiness of Sengudi’s remarkable costumes, and the slight silliness of seeing them on such mature artists, the short performance resonated with a sincere positivity. The radically inventive, provisional energy of Freeway Fets had dissipated; the museum space, however, provided a sense that with art-historical hindsight, artists whose work once thrived in marginal contexts might eventually be acknowledged on an official level. Returning to tactics from their youth, these artists reminded us that thirty-plus years later, Now Dig This! marks a kind of institutional debut.

The exhibition radiates with the warmth of this and other reunions, but the positivity is predicated on the negativity that had marked previous exclusions. Viewing the works of Hassinger, Nengudi, and Jenkins, one can imagine various chapters of art history in which they should have been included all along. Nengudi’s brilliant sculptures, also using pantyhose and sand, can be thought of in an African American art context, but also should have always shared galleries with Louise Bourgeois, Yayoi Kusama, Eva Hesse, Lynda Benglis, and other well-known artists who have challenged minimalist premises with crafty, biomorphic forms. Hassinger’s ambitious formalism only obliquely suggests an African American context; the works included in Now Dig This! make industrial-material references that suggest human bondage but also modernity more generally. Jenkins’s presentation in the show, occupying three video monitors that play lengthy loops of original video, is among the most revelatory—with the only video on view; Jenkins seems to have been alone among his peers in working with that new medium, a fact he partially attributes to his atypical access to university editing facilities.10 A few videos made with black-and-white Sony Portapak video technology document the art and music scene of the 1970s, including stirring portraits of other artists in the show (In the Spirit of Charles White,1970, and King David, 1978). Another group of works shot on an early color camcorder, such as Inconsequential Doggereal (1981) and Without Your Interpretation (1983), transition into rather experimental forms, employing trippy montages, theatrical narratives, combinations of appropriation and original text and image, and Jenkins’s own free-jazz musical performances, all of which present a kind of black criticality toward established social conditions. Now Dig This! recovers these materials, along with amazing pieces by predecessors Saar, Outterbridge, Charles White, Melvin Edwards, Alonzo and Dale Davis, and others, providing a platform for their current consumption, while evoking a melancholic sense that they should have been available to the mainstream art audience all along.

Like Now Dig This! many of the current exhibitions illustrate apparently positive differences between now and then. Fascinatingly, PST’s historicizing structure draws critical attention to the elided period, 1981–2010, when transformative debates around the politics of representation accompanied a reformation of the social sphere to acknowledge the interests of women, people of color, queers, and others. Identity politics influenced the art milieu. More broadly, a cultural assimilation of a diversity-tolerant form of liberal pluralism made different kinds of representations possible within powerful institutions during these years. Much remains unsaid in PST literature about the ways a second history prepared this previous history for the present. In today’s Los Angeles, when formerly marginalized artists and practices show up to be noticed, there is little outcry about a culture war being waged. Rather than silencing marginal histories, many L.A. curators used the various levels and kinds of support provided by the Getty to give voice to less-familiar artists and narratives, and to interrogate the reasons their works fell out of the dominant history. Many PST shows, like those mentioned above, raise deep questions about the notions of center and periphery, and whether or not that spatial sense of power is indeed still operable in 2012 in a centerless city, within a postmodern, multicultural linguistic space, or under the auspices of a collaborative, networked museological model. The ambivalent relationship to mainstream institutions and histories may indeed be a profound shift that says as much about now as it does about 1980.

In his 1993 catalogue essay for the exhibition The Theater of Refusal: Black Art and Mainstream Criticism, at the University of California Irvine, the artist Charles Gaines, my father, wrote, “It is virtually impossible to invoke the discourse of marginality without buttressing the implacable edifice of the mainstream. The black artist is engaged in a battle for her identity, and there is no possible victory, for to be marginal is to be in the battle.”11 At the height of the identity-politics moment, Gaines describes marginality as an embattled position. The oppositional presence of the excluded serves to mark the centrality of the dominant. Gaines is among the artists reconsidered in PST, with work in Now Dig This! and Under the Big Black Sun, and a musical performance project included in the Performance and Public Art Festival. Gaines worked between Central California and New York City in the late 1970s, and was not part of a Los Angeles scene until the early 1990s. Despite this, his work serves important functions in the shows that include it. Now Dig This! slyly singles out one of the few African-American subjects in his Faces series (1978), so that Gaines serves as an imaginative link between black California and New York conceptualism, a link that is tenuous to say the least. Before a deconstructive critique linked conceptual practices to identity projects, Gaines’s work, which appeared in mainstream commercial venues, was not addressed as black art, despite whatever practical limitations Gaines may have experienced as a black artist. Accordingly, his text-based work Incomplete Text (1979) is grouped with works by Baldessari, Allen Ruppersberg, and Bas Jan Ader in the MOCA exhibition, orienting their pieces around formal rather than cultural similarities, presenting Gaines as an innovative text artist rather than an innovative black artist. In one show, race is a positivist force unifying diverse materials; in the other, material considerations propose transcendence over the limitations of identity. A resurgence of interest in Gaines’s work suggests that some of the tension between black artist and conceptual art has receded of late, even since the time of his 1993 Theater of Refusal essay, which outlines the ways in which race framed the critical reception of artists working at that time. Interestingly, while no longer couched in terms of battle, that process can still be identified in the two ways Gaines’s work is dealt with in these exhibitions.

Gaines quotes the artist Adrian Piper in The Theater of Refusal, who points out conspiratorially: “I really think poststructuralism is a plot! It’s the perfect ideology to promote if you want to co-opt women and people of color and deny them access to the potent tolls of rationality and objectivity.”12 As Piper indicates, just as marginalized people sought to validate their own subject positions, critical theory came around to dismantle the very subject status to which these others had attained. At the same time, identity-oriented artworks and exhibitions were entering mainstream institutions and markets during the 1980s and 1990s. The exhibition Gaines curated and his essay illustrated that among the black artists who had by then begun to be recognized, their works were typically received through the idea that race is a limiting factor. In his study of critical responses, this limitation was either read as an anti-aesthetic failure of the works, or a productive source of specific imagination and creativity for the artists.

That latter interpretation, which focuses on difference as creative inspiration, engaged in a kind of pro-difference politics that fostered notable shows of the period and in the decades since. These range from the 1993 Whitney Biennial and many other projects associated with the curator Thelma Golden that have focused on African American identity and representation, to exhibitions like the fairly recent WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, curated by Connie Butler in 2007 at MOCA, which brought together major women artists whose works had launched critiques of the patriarchal claims embedded in universalist ideas of art. These and other shows made cases for both personal subjectivity and social pluralism as appropriate art content, moving from a place of invisibility for blacks, women, and others into an art world that now at least nominally acknowledges the diversity of its participants. While the term “identity” still causes alarm when it precedes art, there is now arguably a basic comfort with the idea that different artists have different bodies and come from different places, and that those experiences influence their works. This, after all, in a different form, is the premise of Pacific Standard Time. As in the broader culture, this sensitivity to perspective has accompanied race, gender, sexuality, and other identificatory structures as they became acceptable elements of not only countercultural, but institutional postmodern art discourse since the 1980s.

Since then, the public art institutions themselves have changed. This is certainly so in L.A. In 1980 the Getty Museum was little more than a Greco-Roman urn collection in Malibu. The Hammer Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art had not yet been founded, nor had the smaller nonprofits that exhibit contemporary art in L.A. and that have also mounted PST exhibitions. Apart from some enduring university galleries and the Watts Tower Art Center, few features remain from that period’s landscape. LACMA did exist at its current, much-expanded site, and, as in the presentation of Five Car Stud and Asco: Elite of the Obscure, it subtly embodies the corrective spirit PST has engendered.

A return to the central question: does this change, in institutions, in representations, in modes of access, represent the amplification of radically different voices or the assimilation of these voices into a normative power structure? A Bakhtinian idea of carnival has its resonances within this citywide festival and its diversity of representations, and might represent one way to think about the answer to the above question. A carnivalesque, ambivalent, dialogic response might be “all of the above.” Despite the Getty’s monologic effort (the institution put a good deal of energy into overseeing all collaborations with smaller institutions and maintaining authority over press releases, schedules, logos, and the like), Pacific Standard Time cannot help but speak with multiple voices, enabling iterations that exceed the Getty’s managerial authority.

The Performance and Public Art Festival, coordinated by the Getty and the nonprofit gallery LAXART, and presented over two weeks in January 2012, further demonstrated these ambivalent forces and, among other things, enabled specific instances for the embodied performance of marginalized racial and sexual subjectivities. The platform served as a site for many actions, reenactments, and inventive responses to the period in question, including a few events with which this writer was involved as a curator, featuring artists whose work has helped frame my own work as an artist working in performance.13 These performance projects, part of a Talks About Acts series I organized in collaboration with Alexandro Segade, demonstrated a range of ways in which identity has been historically performed by California artists, and the shifting terms by which these performances can now be acknowledged and understood. The assimilation of these performances into the visual-art institutions that hosted them is another marker of a shift in the relationship between central authority and its irritants. Two of these projects brought race and performance into intimate contact: works by the group Bodacious Buggerrilla and by Eleanor Antin.

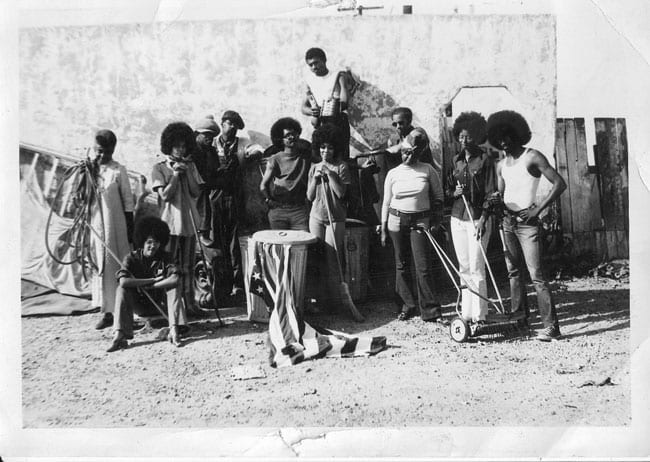

Supported by the Getty and hosted in its own auditorium, the reunion and reprise performance of a radical street theater troupe, the Bodacious Buggerrilla, began the series officially as a “pre-festival event.” The differences between the Getty Museum and the Bodacious Buggerrilla were stark. Founded by the artist Ed Bereal, the troupe satirized American politics and black political life in short plays and actions between the late 1960s and the early 1980s. The reunited troupe, composed of Bereal, Larry Broussard, Bobby Farlice, DaShell Hart, Tendai Jordan, Barbara Lewis, and Alyce Smith Cooper, came together for the first time in many years to perform a play and hold a conversation. They reenacted their short piece Killer Joe, in which a pretentious pimp gets taken down a few notches by his friends, by the Man, by the pigs, by his own hos. At the end of the play, despite his boasting, Joe is left pantsless, carless, and cashless, chased off the stage by his Bible-wielding mother. Timely in South L.A. during the early 1970s, this performance resonated with all sorts of real dynamics of that neighborhood. With the performers now in or near their seventies, the presentation in an auditorium atop a Brentwood mountain served to complete a historical record, to consecrate the group’s formerly fringe activities, and to contain those elements within the bureaucratic limits of the institution—but also to do the affective work of reunion that operated beyond institutional oversight. In the time spent preparing for, mounting, and reflecting on the event, bonds of friendship and camaraderie were renewed, important narratives were passed on and reconsidered, the bravery of the group’s antagonism was valued, and a sense of political continuity between then and now was articulated, for better or for worse. As moderator and facilitator of the event, I spent two days with the Bodacious Buggerrilla that were among the most memorable and influential experiences I’ve had working in the cultural sphere.

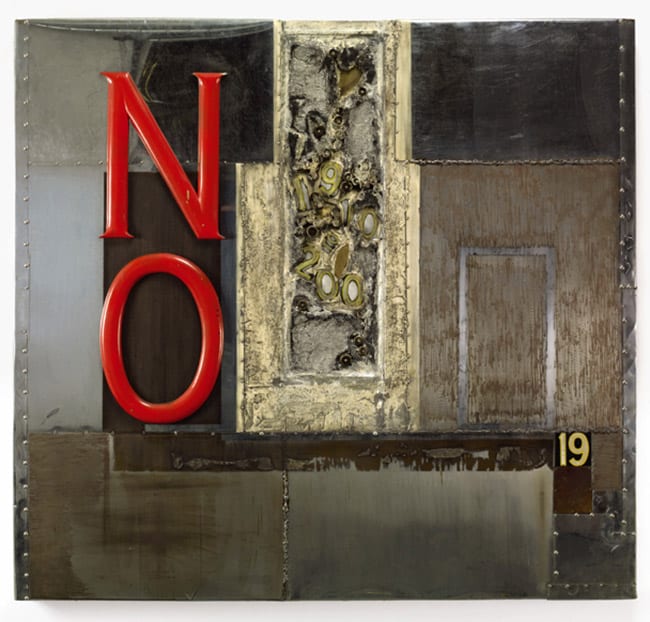

The troupe’s director, Bereal, whose art figured prominently in the Getty’s own PST exhibition, had previously used assemblage to draw racial critiques from found objects. Disillusioned with the art world, he dropped out and became a performer. An anthology of the political theater of the time captures his thinking:

Yeah, because it’s like a never-never land; it’s like a whirlpool in the sense that it feeds on itself. You don’t need anybody, man, you know? You do your pictures; you’re in a milieu. There are old, fashionable, wealthy ladies who don’t know where they are; but it’s fashionable to buy your stuff. It’s fashionable to invite you to their house, have cocktails and you do somethin’ weird, which increases your number, which sends you back, and you do another picture and then you come out to the cocktail party again. You do somethin’ weird for them and give them a little story to tell the rest of the week; and you make some bread off it because you sell ’em a whole piece: Here’s a picture by the guy who just did the funny story I just told you, right. And everyone else goes OOOOOHHHHH and that leads to the next cocktail party, you know, and it just goes on and on and on like that; it don’t mean nothing at all. And all the time you are truckin’ back to the ghetto, you know; I Am Going Back to the Ghetto. And all your fellow ghetto residents are going wow, man, you have a heavy thing goin’, wow, that’s really heavy. And you even think you got a heavy thing going. And the little rich lady thinks she’s got a heavy thing going. She say: Well, I know some people in the ghetto. And her friends say: Really? Wow, you know . . .14

Bereal’s transition from the art circuit to his own collective was a radical move. His audience changed, his work changed, and the risks changed. It is important that art is figured here as a compromised, elitist pastime, while theater is poised to engage with political realities. Bereal’s recollections of the Bodacious Buggerrilla, described in the discussion at the Getty, include run-ins with FBI COINTEL agents who were cracking down on black radicals. In an allusion to the dangers of this work, the troupe reenacted an intervention it used to perform: during a politically direct monologue by Jordan describing the forces of conservatism that still operate in oppressive ways, a white audience member jumped up from his seat, argued with the cast using racist language, and theatrically shot Jordan with a cap gun. Jordan, prepared with a pellet of stage blood, was soon covered in red and fell to the floor. The stagecraft of this moment was a little less smooth than it might have been forty years ago. It perfectly expressed, however, the social context for the original work, the continuously relevant real-life stakes of the political discussion, and the transgressive quality of this group, which had not warned me or the Getty that this messy episode would occur. While the Getty staff’s nervousness about the event was evident to those of us who organized it and to Bereal himself (who carried his costume billy club with him during talks with staff), the museum’s representatives proved quite flexible in their ability to support and accommodate black street theater as an example of important art from the period. No one on our end was reprimanded for the unannounced spilling of fake blood all over the stage.

Eleanor Antin’s Before the Revolution was the grand finale of the Performance and Public Art Festival. Staged as an evening-length play at the Hammer Museum, it was a reworking of Antin’s original narrative piece, performed by her and large Masonite dolls at The Kitchen in New York in 1979, for this expanded return. The play follows one of Antin’s well-known characters, Eleanora Antinova, the black ballerina. In the 1970s, Antin, whose work brought eccentric theatricality to the emergent performance art of the time, not only performed Antinova, but attempted to live as her for a period, wearing slightly dark makeup and enacting a convoluted fantasy through which race, gender, and artistic mastery were cleverly entangled. While Antin’s practice of cross-racial performance did and does raise eyebrows, it was a rare instance of racism being critically addressed within the milieu of that era’s dominantly white cadre of influential artists. In Antinova’s scripted arguments with her ballet master, questions of representation are tied to the powers of Eurocentrism and framed through estranged performances, drawing attention to ideas of performativity that would be more fully articulated in the art and writing of coming decades. The questions raised earlier about inclusion and representation are acted out in Antinova’s insistence that she play Marie Antoinette, and Diaghilev’s insistence that she cannot, that her body only authorizes her to play Cleopatra or Pocahontas.

In his curator’s note for the 2012 program, Segade explains:

The character is quixotic and quizzical, a great dancer whose career is negatively impacted by the fact of her race in contrast to her nationality (black v. Russian), her over-determined relationship to gender (ballerina!), and her place in history (Classicism v. Modernism v. Post-). . . . This radical figure functions as a site for critique of the contradictory and constructed divisions among races, classes, careers, histories, and even artistic forms.15

Segade taps into the disciplinarity that has been challenged throughout PST, drawing an important parallel between formal artistic distinctions and cultural divisions, and proposing the possibility that the critique of each is reflected in the other. Antin’s own 2012 program note focuses on the difficulties of mixing theater and art that vexed her original work:

Performance artists were supposed to position themselves as anti-theatre. So Yvonne Rainer called her marvelous, literary, dramatic movements “anti-dance.” Why would a sophisticated talented artist think that “dance” only meant ballet, modern, folk, ballroom, whatever? Why were sneakers any less a dance prop than toe-shoes? When Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh were chained together for a year, wasn’t that theater? Wasn’t Bas Jan Ader’s kamikaze engagement with the Atlantic Ocean theater? More recently when Marina Abramovic in her favorite role of goddess held court inside the palace of modern art and looked into the eyes of strangers and changed their lives, wasn’t that theater?16

Antin’s stirring defense of theater, long-declared enemy of modern art, accompanied a new production in which she turned the primary performance responsibilities over to a cast of actors and a theater director. Early in the process, Alex and I encouraged Antin to cast an African American actress to play Eleanora Antinova. On my part, this was both from fear of facilitating, explaining, and even watching a blackface performance, but also from an equal interest in finally giving Antinova a black voice. In her piece, Antin had divided the performing presence between her authorial body and the inanimate dolls, a Brechtian critical complexity that could support the difficulties of the racial performance. But the piece was always designed as a play, and Antin’s intention was always that it could be performed as such. Here was the opportunity to embody the characters in a troupe of actors under the artist’s direction, reworking the role of identity vis-à-vis character. Here, the ideas of shifting racial categories and migrating art disciplines transformed each other. This project emerged as a central element of the festival, subject of several articles and profiles, symbolizing the recuperative powers of the series. In carnivalesque manner, these irresolvable categorical problems served to characterize the entire project.

These and other festival projects exceeded the official art-historical order, bringing unpredictable live interactions into the Pacific Standard Time sphere, and further insisting that while many things were done wrong in the past, some things were actually done quite well. It has been quite an experience to see Los Angeles of the present unfold backward through time, and to interrogate the terms by which L.A. art has been rearbitrated and renegotiated. The attempt to standardize a history of Southern California art has been met by the local tradition of history-less-ness that has made Los Angeles a place of radical reinvention. By depicting history not as a centralizing progressive force but as a collection of forces shaped by a particular provincial context, the Getty has used its singular resources to empower a series of historical interventions. The coalition of dominance and exclusion has produced a number of wonderful exhibitions and projects, plenty of awkward bureaucratic mismatches, and a revised record of alternative art histories. The local effort may appear as the apotheosis of provincialism to the outside world. Regardless, the project works beyond the specific historic content put forward, prominently modeling a contemporary arrangement of networked power, a structure that exceeds any central ordering authority, and drawing attention to that power’s interest in and ability to administer differences.

Malik Gaines is assistant professor of art at Hunter College, CUNY, and a member of the group My Barbarian, which has performed and exhibited internationally. He has contributed writing to numerous art publications and catalogues, including monographs for Mark Bradford, Andrea Bowers, Sharon Hayes, Glenn Ligon, and Wangechi Mutu. Gaines holds a PhD in theater and performance studies from UCLA, having researched the transnational politics of race and gender in performances of the 1960s.

- From the 2011 video Ice Cube Celebrates the Eames. During Pacific Standard Time, the video could be seen at the PST website. It is now (May 9, 2012) available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=FRWatw_ZEQI and several other websites. The video is also the source of the epigraph for this essay. Further quotations in this paragraph are from the same video. ↩

- See Chon A. Noriega, “Conceptual Graffiti and the Public Art Museum: Spray Paint LACMA,” in Asco: Elite of the Obscure, A Retrospective, 1972–1987, exh. cat. (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2011), 260. ↩

- Artforum, October 2011, cover. ↩

- See Holly Myers, “Confronting the Darkness of Ed Kienholz’s ‘Five Car Stud’ at LACMA,” Los Angeles Times, August 28, 2011. ↩

- See Michael Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (London: Allen Lane, 1977). ↩

- Myers. ↩

- See Kellie Jones, introduction to Now Dig This!: Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980, ed. Jones, exh. cat. (Munich, London, New York: Prestel, 2011), 22. ↩

- Ibid., 20. ↩

- Nick Stillman, “Senga Nengudi’s Ceremony for Freeway Fets and Other Los Angeles Collaborations,” East of Borneo, December 7, 2011, online at www.eastofborneo.org/. ↩

- Ulysses Jenkins in conversation with the author, January 2012, Los Angeles. ↩

- Charles Gaines, The Theater of Refusal: Black Art and Mainstream Criticism, ed. Catherine Lord, exh. cat. (Irvine: Fine Arts Gallery of the University of California, 1993), 16. ↩

- Adrian Piper quoted in Gaines, 3. ↩

- To be completely clear: I serve on the staff of LAXART as curator-at-large. Alexandro Segade and I selected various performance works for the festival in the context of the Talks About Acts series we co-organize. My discussion here of two performances from the series is in no way intended as a review of the works, but rather as a consideration of themes and issues raised in the presentations—some of them rather surprising to me and the other organizers. ↩

- Ed Bereal quoted in John Weisman,Guerrilla Theater: Scenarios for Revolution (Garden City, NY: Anchor, 1973), 102. ↩

- Alexandro Segade, “Curator’s Notes: Eleanor Antin’s Revolution,” program note for Eleanor Antin, Before the Revolution, January 29, 2012, Hammer Museum, UCLA. ↩

- Eleanor Antin, program note for her Before the Revolution, January 29, 2012, Hammer Museum, UCLA. ↩