From Art Journal 71, no. 3 (Fall 2012)

The reasons for their problems are not difficult to guess: they are under-employed and overly-sociable; they are deprived of the chance of both success and failure, and receive their food, their shelter, and their mates as welfare handouts; their relationship to their keepers—the symbol of both their security and their internment—is ambivalent if not overtly unhealthy. Under such conditions it is not surprising that they should spend their days concerned with unproductive sexual experiment, peanuts, popsicles, transistor radios, and popularity.

—John Szarkowski

The time for art as diversion is over.

—Jean Toche

Monkey Business

In a 1981 interview with Barbaralee Diamonstein, the photographer Garry Winogrand called the media’s obsession with politics during the Vietnam War “monkey business.”1 The statement is tinged with irony, not in its mockery of

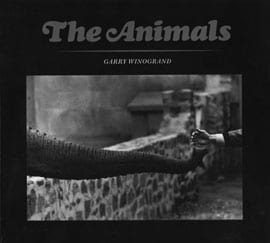

the role of photography to depict politics and war explicitly (Winogrand having been a professional photographer), but in the fact that Winogrand was known as a photographer of “monkey business.” In 1969 Winogrand published The Animals alongside an exhibition of the same name at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA). Though it has never been seen as such, it was a timely project, and represents a satire of American society during the height of a war “unassimilable” by popular culture.2 By interpreting Winogrand’s The Animals as a social satire, we can reinvest the photographer’s work with a redemptive quality it was seen as lacking due to its presentation by MoMA and show the relevance of Winogrand’s photography within the Vietnam War era.

During the period of US military involvement in Vietnam (1955–75), responses to the war in various cultural fields were indirect, with artists preferring appropriation, allegory, and satire as critical strategies.3 Even in protest, artists of the time chose not to confront politicians responsible for the war, but museums of art, which were seen to be both ambivalent and implicated in the war. Two artists’ groups, each formed in 1969, were typical of this war protest by proxy. The first was the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC), formed in 1969 as an organization to enact social change within cultural institutions such as MoMA.4 A second group, which emerged from the AWC, was the Guerilla Art Action Group (GAAG).

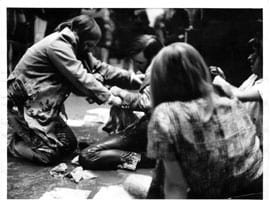

Confronting the Vietnam War by confronting the museum, thus conflating politics with aesthetics, GAAG’s tactics were blunt. Mid-afternoon on November 18, 1969, the four primary members of GAAG—Jean Toche, Jon Hendricks, Poppy Johnson, and Silvianna—entered MoMA’s lobby and distributed copies of a letter with the heading “A Call for the Immediate Resignation of All the Rockefellers from the Board of Trustees of the Museum of Modern Art.” The letter outlined links between the Rockefeller family and the war in Vietnam, highlighting corporate profits members of the family would have seen as a direct result of the escalating conflict. After passing out their demands, the four members of GAAG began to quarrel; grunting, screaming, crying “rape,” they tore at each other’s clothes, ripping open sacks of beef blood they had hidden beneath their clothing. As blood spilled, the members fell to the ground, writhing as if in pain and the grip of death. Pausing for only a moment, the artists quickly rose, left the lobby, and subsequently sent an account of the action and several photographs to news agencies. What became known as “Blood Bath” appeared in media outlets such as Newsweek, drawing remarkable attention to the efforts of both GAAG and, by extension, the AWC.5

“Blood Bath” was less a successful political action (Nelson Rockefeller did not resign from MoMA’s board), than a prescient moment in the public perception of the Vietnam War. On November 12, 1969, a week prior to GAAG’s performance, the journalist Seymour Hersh broke news of the events that would become known as the My Lai Massacre—an incident on March 16, 1968, in the Son My village of Vietnam that resulted in the death of 504 Vietnamese civilians. On November 14, Winogrand snapped a picture of a large peace demonstration in Central Park, in which thousands of balloons were released representing the rising death toll in Vietnam.6 The following day, November 15, saw a nationwide moratorium against the war; the demonstration in Washington represented the largest rally against the war to date. Then, on November 20, 1969, the Cleveland Plain Dealer published army photographer Ron Haeberle’s photographs of the massacre at My Lai. The most striking of these images became a rallying point for those opposed to the war in Vietnam, proof of a policy run amok, and an echo of GAAG’s documentation of “Blood Bath.”7

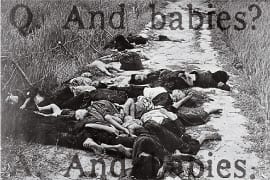

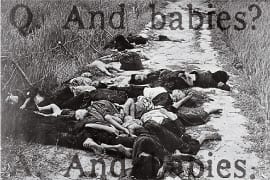

Following the publication of some of Haeberle’s photographs in Life on December 5, 1969, the AWC contacted the photographer about reproduction rights.8 It planned to make a poster in collaboration with MoMA, using Haeberle’s image, adding text, printing fifty thousand copies, and distributing the work for free.9 The poster would be plainspoken, reading, “Q: And babies? A: And babies.,” thus relaying the graphic violence found within the photograph.10 Though MoMA initially responded positively to the collaboration, by the first week of 1970 its board of directors rejected any involvement in the project. A MoMA press release dated January 8, 1970, stated, “Mr. Paley [William Paley, board president] said that he could not commit the Museum to any position on any matter not directly related to a specific function of the Museum.” By this point a printing house had already agreed to donate time and materials for the project, and thus the poster went ahead, without the museum’s endorsement. With MoMA’s public retreat from the poster project, the AWC staged a protest against the war and the museum, using the poster as its rallying point. Gathering around one of the great works of antiwar art, Pablo Picasso’s Guernica of 1937, the protest expressed not only artists’ interest in using art as a means for public comment on the war, but also suggested MoMA’s ambivalence toward contemporary politics.11

As the historian James Aulich wrote of Q: And Babies?, the success of the poster was “guaranteed by the museum’s failure to co-operate: this rendered institutional appropriation of the art object impossible, and so left intact wider redemptive and socially transforming ideals common to most modern art.”12 Aulich’s presumption here is that art can only be redemptive, and socially transformative, if it exists outside the museum. At the time, a key member of the AWC effectively agreed with Aulich’s later premise. The critic and curator Lucy Lippard wrote, “The first decision about the execution of the My-Lai massacre protest poster . . . was that it be ‘nonartistic,’ that no individual artist’s name be connected with it, that the ‘art’ be a documentary photograph.”13 As Lippard reaffirmed later, modern art was seen as “safely ensconced in its own world.”14 Documentary photography, not considered by Lippard and the AWC as art, would therefore provide a productive means of dissent outside the art institution’s perceived ambivalence.

The appropriation of Haeberle’s image for an antiwar statement, and the manner in which such a sentiment could permeate the photograph only in its appearance outside a museum, suggests an identity crisis for documentary photography at the time. Documentary-style photography, a mode originating in the United States during the 1930s that carries a distinct subjectification of facticity, was on display at MoMA during the events held by GAAG and AWC.15 In particular Winogrand’s The Animals was on view from October 24, 1969, through January 18, 1970. But, as Lippard’s and Aulich’s statements imply, such “art” was socially ineffective. At the same time, photographs found outside the museum, such as Haeberle’s images of My Lai, were viewed as socially effective.

The director of the Department of Photography at MoMA during these events was John Szarkowski. His program of exhibitions during the Vietnam War era can be seen as typical of the museum’s apparently insular and self-serving agenda. Szarkowski’s exhibitions scarcely touched on the issue of Vietnam, or photography and Vietnam, and when they did, they often undermined photography’s role as impartial evidence. Though Szarkowski was present at some initial meetings between the AWC and MoMA, the group’s demands never trickled into his curatorial efforts as head of the Department of Photography.16 His curatorial program forged a modernist aesthetics of photography that valued the medium’s formal attributes over social content, thus resurrecting American documentary-style photography in the 1960s, and with an eye for individualism. Winogrand’s The Animals fit Szarkowski’s bill quite well.

The Animals was Winogrand’s first solo exhibition at the museum, a major accolade for any photographer then as now. Though he had had several exhibitions of his work prior to The Animals, Winogrand was interested in publishing the zoo photographs as a book.17 The book was not a large volume, but included forty-two images, five more than the exhibition. All of the images in The Animals were made at the Central Park Zoo and the Coney Island Aquarium, with the earliest dating to 1962.18 Despite a culture apparently obsessed with animalism, and apes in particular, Winogrand’s book was not particularly successful on the commercial market.19

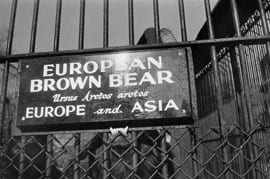

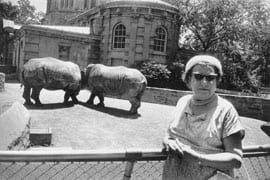

The Animals is not, however, an unremarkable book. Consider the cover image, which updates Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam for the photographic age.20 Instead of God meeting Adam’s hand, we have a zoo-goer feeding an elephant’s trunk. Where Michelangelo chose the creation of man, Winogrand chose the naming of beasts for his interpretation of Genesis. As with the strong diagonal formed by the wall in this image, Winogrand emphasized the distance between the irrational animal and the “civilization” of humans by foregrounding the zoo’s enclosures throughout his book.21 For instance, on page 28 we see all enclosure, save for a set of lower teeth almost casually tearing at a sign naming the wild creature within. This image is juxtaposed with a serene moment on the facing page: a man, smoking, stares into the eyes of a rhinoceros, whose horn has previously been removed. With such internal juxtapositions, the images in The Animals are at once ironic, humorous, and at times downright bizarre. Early in the book, for example, we view a woman in rhinestone-trimmed glasses posing for a portrait in front of a pair of rhinos. Later, on page 27, a couple of elephants catch the gaze of a couple in matching checked shirts, while another human couple watches from within a cardboard box. On page 32, a woman gazes at a llama; the woman wears a leopard print coat, while the llama wears a coat of cashmere.

In a short text reproduced in The Animals,Szarkowski discusses the work with a focus on the photographs’ formal attributes. The curator notes that Winogrand’s zoo “is a surreal Disneyland where unlikely human beings and jaded careerist animals stare at each other through bars, exhibiting bad manners and a mutual failure to recognize their own ludicrous predicaments.” “As complex and simple as ancient parables,” Szarkowski continues, Winogrand’s photographs succeed because of “the richness of their observation and the sophistication of their graphic command.” As is often the case in Szarkowski’s writing on photography, he generalizes about the content of the material as a means to praise the photographer’s overall formal “virtuosity.”22 Such judgment of photography on the basis of a photographer’s individualized sense of style was established in Szarkowski’s 1967 exhibition New Documents. Itfocused on three photographers (Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, and Diane Arbus) who were commercially successful, relatively unknown, and yet stylistically distinct. Through their work, Szarkowski sought to redefine photography by declaring these acolytes of American documentary style devoid of ideology, thus leaving the photograph to become a conduit of the photographer’s self.23

Szarkowski’s rejection of documentary photography’s redemptive role and his lack of engagement with contemporary issues such as the Vietnam War were criticized as conservative and apolitical. Szarkowski did not avoid speaking to the subject though. In the introductory essay to his 1978 exhibition Mirrors and Windows, he argued that photography failed “to explain large public issues,” such as the Vietnam War.24 Drawing on a well-known image from Vietnam, taken by the photojournalist Larry Burrows, Szarkowski further wrote that photojournalism cannot “serve either as explication or symbol for that enormity [Vietnam].” He continued, “For most Americans the meaning of the Vietnam War was not political, or military, or even ethical, but psychological. It brought us to a sudden, unambiguous knowledge of frailty and failure. The photographs that best memorialize the shock of that new knowledge were perhaps made halfway around the world, by Diane Arbus.”

Szarkowski’s interpretation of Arbus’s work cut against the grain of the loudest contemporary responses to her work. Critics positioned her photography as either exploitative or apathetic. Consider Susan Sontag, who critiqued Arbus’s work in her 1977 book On Photography. Sontag claimed that Arbus’s photographs of “freaks” makes us feel indifferent, and they keep us unaware of any social ramifications to understanding others.25 While Sontag only implied that photographic apathy was the result of viewing photography within a museum, the artist and critic Martha Rosler saw the museum’s role as paramount. In her 1981 essay “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography),” Rosler criticized Szarkowski’s position. Writing of the New Documents exhibition in particular, she noted that Szarkowski “makes a poor argument for the value of disengagement from a ‘social cause’ and in favor of a connoisseurship of the tawdry.”26 She observes, “The line that documentary has taken under the tutelage of John Szarkowski . . . is exemplified by the career of Garry Winogrand, who aggressively rejects any responsibility (culpability) for his images and denies any relation between them and shared or public human meaning.”27

Despite the efforts to position Szarkowski’s curatorial program, and Winogrand’s work in particular, as socially disengaged, the photographer’s documentary tendencies prove otherwise. On the many walks Winogrand took through Central Park in the mid-1960s, in part taking photographs at the Central Park Zoo that would end up as part of The Animals, he often attended and photographed protests, demonstrations, and other political events that can inform our understanding of the Vietnam War era.28 Furthermore, Winogrand was fascinated by how the media transformed newsworthy events and persons into spectacle. Winogrand’s 1960 photograph of John F. Kennedy shows the President from behind and juxtaposed with his own face on a television screen at the bottom of the image. Images such as this, or his photograph of the Apollo 11 liftoff, which focuses on mediation rather than the actual event, resulted in his 1977 photobook Public Relations. If Szarkowski’s modernism valued the individual behind the lens, Winogrand’s presence (camera in hand) at critical political and cultural events intimates a social realism that critics and champions alike have overlooked.

The curator’s job, according to Szarkowski, is “rather similar to the job of the taxonomist in a natural history museum. You don’t have to collect and stuff every song sparrow in the world, but you’re especially interested in those that seem to be, in some way or another, a mutation, a little different.”29 Winogrand was such a mutation. With a distinctly subjective stylistic sense—the tilting frame a marker of the photographer’s quick hand and eye—Winogrand’s vision was at once off-hand and focused; horizons list while vertical elements stabilize.30 Szarkowski lauded the work’s “condition of perpetual contingency,” and reinforced Winogrand’s idiosyncrasy by claiming him as an early American adopter of “new style” European photography.31 As Szarkowski wrote of Robert Doisneau, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Alexey Brodovitch, and Robert Frank, “The goal of the new work was not clarity but authenticity.”32 Adaptation to history, as much as individualism, was central to Szarkowski’s taxonomy. As the curator wrote, Winogrand was a “primitive,” a “raw talent,” whose work was “undisciplined” before coming under his tutelage at MoMA.33 While Winogrand sought “the human condition,” Szarkowski’s discipline trafficked in the peculiarities of Winogrand’s style rather than content.34 cannot disguise its constant attention to the human condition.” Coleman, “Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand at Century’s End,” in The Social Scene: The Ralph M. Parsons Foundation Photography Collection at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, ed. Max Kozloff (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2000), 12.] Though Winogrand’s subject matter was at times misogynistic (as in his 1975 publication Women Are Beautiful), it was within such patriarchal conditions that Jonathan Green found “the possibilities of moving beyond social comment to social satire.”35

The Animals is Winogrand’s most profound “social satire.” Even Szarkowski saw the work as Winogrand’s “most fully successful,” not the least for its “comic drama.”36 Through their humor, Winogrand’s zoo pictures remind us that as much as we go to the zoo in order to view animals, we also go there to view ourselves. A few images stand out in this regard. On page 6, back at the rhino display, a woman is entertained by two kids monkeying around, rather than by the rhinos’ placid demeanor. In a more self-reflexive work on page 14, we find a man outside a large bird’s cage, focused on and perhaps trying to figure out the camera in his hands. Another man walks past, a camera around his neck, gazing between the bird and the man, imagining the photograph he is not taking. Last, on page 3, a young boy points a toy gun at the face of a bear; the bear sticks out its tongue in response. The scene is crowded, as zoos often are, and we (the zoo-goers, positioned there by Winogrand’s camera) cannot help but wonder at the boy’s hostile gesture within the zoo’s confines, a site where animalist aggression is assumed to be safely tamed.

Four Legs Good, Two Legs Better

At the center of the Art Workers’ Coalition protests against MoMA was a photograph taken by Haeberle at My Lai. Instead of fetishizing the singular object hanging on the museum wall (as we might see in Winogrand’s exhibition at the time), the AWC’s poster embraced the ease with which photography could be a form for the masses, and in that way persuasive. To use a photograph as a means of mass communication, and to assert that such a use is “art,” as Lippard had, realigned art as a means to public action, rather than as a mode reserved for the privatized interest of a connoisseur. If we are to accept this reformulation of art as socially active, in its use of photography, mass media, and reproducibility, it is necessary to consider Haeberle’s production of the image. For, unlike photography viewed in a museum, Haeberle’s images existed primarily as reproductions, not as original works of art, and were vital due to their public presence.

Sergeant Ron Haeberle was a US Army public information officer assigned to Charlie Company’s 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, and 11th Light Infantry Brigade. The photographs from which the Q: And Babies? image emerged were all taken on a single day, March 16, 1968, in the Vietnamese village of My Lai. Haeberle carried two cameras with him that day. One was his army-issued Leica camera, carrying black-and-white film, the second his personal camera, a Nikon, loaded with color slide film.37, vol. 2: “Testimony,” book 11: Haeberle (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1974), 54, 58. In vol. 3: “Exhibits,” book 6, “Photographs,” images P-43 and P-70 reproduce contact sheets from two rolls of black-and-white 35mm film. As Haeberle notes in this testimony, he may have in fact been carrying three cameras that day—one with color slide film, and two with black-and-white.] The slide film, his personal color photographs, would not be developed until Haeberle went off duty following the My Lai incident.38 The standard protocol with the other two rolls of film, the black-and-white, was that they be left with the Army’s Public Information Office, which would then develop and consider the resulting images for internal publication.39 Though Haeberle chose to publish his personal images (those in color), first in the Cleveland Plain Dealer on November 20, 1969, and subsequently in Life magazine the first week of December 1969, their most important appearance may have been alongside the black-and-white images in volume 3, book 6 of the Report of the Department of the Army Review of the Preliminary Investigations into the My Lai Incident in 1970 (commonly named the “Peers Inquiry”).40

The first image Haeberle made on March 16, 1968, was in color—a helicopter convoy arriving at “Loading Zone Dottie” in the midst of transporting troops to My Lai.41 When Haeberle arrived on the ground, he set about his work; later he was forthright about his role: “My job as a photographer [was] to take pictures, a normal reaction I have with a camera, just picking up and keep on shooting, trying to capture what is happening around me. I feel that the camera did take over during the operation. I put it up to my eye, took a shot, put it down again. Nothing was composed.”42 Despite that statement, it later became clear that Haeberle’s photographs were composed. Though each individual photograph may not have been formally preconceived, Haeberle took care to take different images with the color film and the black-and-white film. Thus, the images he would keep for himself, the content of which remained unknown to the army until its initial investigation in August 1969, were strikingly different than what he was making for the Public Information Office.

If we look at the “Exhibits” submitted by the army for the Congressional investigation into the My Lai incident, the differences between the personal and the official photographs are clear.43 Scanning the first twenty-five images in this legal exhibit, which represents the first roll of black-and-white film, there is scarcely any evidence of massacre, but that is not to say we do not witness the terror of war. The Vietnamese pictured, primarily the elderly, appear full of fear as the US soldiers approach, as does the face of Private Herbert Carter, the only American to die that day (from a self-inflicted wound). We then see American servicemen taking a break, followed by a solider almost casually setting fire to a “hootch,” or hut. The following images add more context to the arson, as well as depicting the gathering of prisoners and villagers. The second roll of black-and-white film, with photographic evidence numbers P-56 through P-69, exhibits similar scenes. (P-numbers refer to the numbering of images in the army report I cite in note 43.) From our standpoint, certain of these photographs depict unexpected compassion. For example, P-21 shows one of the outfit’s Vietnamese translators, Sergaent Minh, speaking with a young Vietnamese boy.44

Seventeen color photographs were reproduced in the photographic exhibits of the army report. Unlike the black-and-white photographs, their narrative is one of horror.45 As one goes through the images, one aspect becomes apparent: the near-absence of identifiable Army personnel. Not only does Haeberle capture the terror of an atrocity invisible in the official black-and-white images, he seems to take care not to include any of his fellow soldiers. I read this absence as composition. Haeberle frames the atrocity in such a way as to not incriminate his fellow servicemen. That said, there are four images where soliders are identifiable—two men stalking a field with their weapons drawn, from early in the operation (P-30), Specialist Capezza throwing rice fanners into a fire (P-35), Private Carter being carried off toward the helicopter (P-36), and Haeberle himself (P-37), reflected in the water as he photographs a corpse at the bottom of a well. With this image, Haeberle’s shooting appears as the only moment of culpability within the color images. As he stated, “I react with a camera and not a rifle.”46

A story Haeberle recounted under oath highlights his camera’s participation in atrocity: “A small child came walking towards me and he needed medical attention, and he was shot through the arm and shot through the foot around the ankle. And, he kept walking towards me, and I kept on focusing, and I kept backing up and backing up. This GI knelt down beside me. I didn’t know it at the time, because I kept taking the camera and backing up. Three shots were fired. The first shot hit him in the stomach. The second shot lifted him up in the air. The third shot put him down. A stroboscopic effect one, two, three. And the body fluids came out of his back.”47 Here Haeberle conflates the act of shooting with act of high-speed photography; the stroboscopic effect recalls the work of Harold Edgerton, whose use of strobe-lighting reduced movement to a series of stills. Haeberle sees the GI’s gun as a camera, just as he sees his own camera as a gun.

Haeberle’s photographs would prove pivotal in the investigation of the My Lai massacre, prompted first by Ronald Ridenhour, who sent letters to numerous political and military leaders in early 1969 detailing the incident at My Lai.48 Using all of Haeberle’s photographs as evidence, investigators could name names, show locations, and reveal the extent of death. Curiously, though, much of Haeberle’s testimony focused less on the horrific scenes in the color images than on a single black-and-white photograph, P-16. To investigators, that photograph displayed not only evidence of dead bodies, but more explicitly the burning of huts, intimating that the Public Information Office (particularly John Stonich, to whom Haeberle reported) should have recognized and therefore reported the violation of war crimes.49

Focused on P-16, an official army image, Haeberle’s testimony scarcely touched on P-34, which was taken closer to the burning structure and displays the atrocity with a force only implied in P-16. As one of the investigators noted, the black-and-white images were “comparatively bland” when seen against the color images.50 This stark contrast led investigators to suspect censorship within the Public Information Office, provoking them to inquire as to whether Haeberle was asked not to take images that would be detrimental to the army’s public image. Stonich testified that he “never instructed photographers not to take pictures of subject matter that would not be released.”51 Haeberle felt differently, stating, “If a general is smiling wrong in a photograph, I have learned to destroy it. What would happen if I had turned my color [film] in? . . . My experience as a GI over there is that if something doesn’t look right, a general smiling in the wrong way, a picture of this, I stopped and destroyed the negative.”52 As we have seen, there is a clear distinction between what Haeberle made in color and in black and white. Despite the Vietnam War being mythologized as a war without censorship, it is clear that such freedom of the press did not apply to the army’s own press corps.

One question that haunted America following the public dissemination of Haeberle’s images in late 1969 was how the war could have evolved to a point of irrationality. As Phillip Knightley elaborated, “The use of raw young soldiers, on a fixed period of service, bewildered by the faceless nature of the enemy, and encouraged to regard the Vietnamese as less than human, made an event such as My Lai highly likely to occur.”53 To Lieutenant William Calley, who was ultimately the sole person convicted in the case, on twenty-two charges of premeditated murder, the Vietnamese “were animals with whom one could not speak or reason.”54 Such a conflation of animal and enemy also surfaced in one of the more absurd legends among GIs: the existence of so called “rock apes,” a band of wild simians that were said to emerge from the jungle and attack US troops with rocks.55 It is clear, in such satirical misremembrances of Vietnam, that GIs not only slandered enemy guerillas by viewing them as gorillas, but that such a derogatory view of the enemy fed a lack of empathy. However, it was not only that American soldiers viewed the Vietnamese as animals, but also that the American soldiers had lost a sense of humanity. As GI Greg Olson recalled about My Lai, “These [were] all seemingly normal guys. . . . For a while they were like wild animals.”56 It was an animalism exploited even by the National Liberation Front (the NLF, or Viet Cong). As an NLF propaganda leaflet, dating from 1968 (after My Lai), read, “When the American wolves remove their sheepskin their sharp meat-eating teeth show. They drink our people’s blood with animal sentimentality.”57 The institutions responsible for the safekeeping of US troops and their training, and thus accountable for rationalizing war (as farcical as that sounds), set them free in a fit of feral action.

Focused on zoos during the Vietnam War, Winogrand’s camera (his “predatory weapon” as Sontag might call it) draws the viewer toward an all but absent institutional boundary between rationality and animality. The zoo, which reconstructs “the wilderness” within “the special, enclosed and policed enclaves nearer to our human homes,” reinforces colonial geopolitics as well as humanity’s taxonomic and architectonic enclosure of nature.58 The events of My Lai reinforced that the debasement and disciplining of another (human or animal) does not exempt the colonizer from irrationality. When viewed in the shadow war, Winogrand’s Central Park Zoo photograph of a boy pointing his toy gun at bear, who responds by baring his tongue, demands attention. What are we to make of the boy’s aggressive body language? The bear’s gesture is humanizing and mocks the boy’s empty threats, but whom might the boy’s gesture imitate?

In the zoo, the role of those tamed and those undomesticated is uncertain. In Winogrand’s zoo, as Green tells us, we see “the human in the animal and the animal in the human.”59 Though the Central Park Zoo was intended “as a way to establish New York as ‘the acknowledged seat of wealth and moral power,’” its public popularity broke down hierarchies of “decorum and order,” thus displaying the “‘ill-assorted’ menagerie” of modern urban space.60

The persuasiveness of Winogrand’s satire lies in the photographer’s ability to use The Animals to alert us to the public’s passive participation in both the restriction and release of our all-too-accessible animalism. Evoked by Winogrand’s repeated framing of the zoo’s enclosures, a general state of conflict is alluded to in The Animals. The tameness of the “wild” creatures in The Animals forces us to realize the irrationality of confining nature. As viewers of the images, like viewers of animals in such parks, we participate in a peculiar, if not cruel, domestication process. If you forgot you were a part of this social landscape, consider pages 18 and 19, where at first another zoo-goer, and then a beluga whale, catch our eye, folding us into the scene. Here, as elsewhere in the book, the line between human and animal, between the domesticated and the wild, appears to have been lost. Similar scenes appear on pages 24 and 25. In these two images, we appear to move from outside to inside the enclosure. The photographer, the surrogate for the viewer, is both contained and liberated.

In this way, The Animals is an allegorical satire not only of humanity in times of war, but also of the photographer’s real work and the cultural contexts between which it commutes. The first epigraph to this essay, which Szarkowski wrote for the book of The Animals, reads as a description both of zoos and of the museum’s relationship to artists. This theme of the enclosure taming human and animal equally culminates in the final images of Winogrand’s book. On page 43 we look into a cage to see a bison and then, beyond, another cage containing a man. We keep the animal, and the animal keeps the man. Finally, in the last plate, a couple embraces, and we watch, apparently from inside an enclosure. Incarcerated, we witness their animal magnetism and are distanced from humanity.

Though we commonly associate satire with literary, dramatic, or cinematic forms, the photography book (a “literarization of the conditions of life” as Benjamin called the form) offers a means for photography to participate in this genre. By making this claim, we can situate Winogrand’s The Animals in the context of war satires from the Vietnam era. These include classic novels such as Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five (1969), Patrick Ryan’s How I Won the War (1963, adapted into a 1967 film), and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (1961).61 Richard Hooker’s M*A*S*H was published in 1968, adapted for a 1970 film, and further adapted for a popular television series that aired 1972–77. Though each dates from the time of conflict in Vietnam (1955–75), none of them addressed Vietnam directly. The focus of each was World War II or the Korean War, though they can be read as indirect condemnations of Vietnam.

Few satires of the period explicitly focused on Vietnam. Norman Mailer’s Why Are We in Vietnam? (1967) critiques American involvement in Vietnam told through metaphor: in the Alaskan wilderness, a father and son go on a hunting trip that descends into chaos. The most fundamentally antiwar satire to emerge from the period of conflict was not a literary text, but a musical play, Megan Terry’s Viet Rock, written and first performed in 1966. As Terry wrote of her use of satire, “Every positive and comic value in the play must be played, and then the dark values will come through with twice the impact.”62 Though typical of war satire in this regard, Viet Rock is rare in that it directly addressed contentious issues such as the loss of innocent life and the draft. A farcical echo of the war’s terror can also be found in the film Night of the Living Dead (1968, directed by George A. Romero), which, according to the scholar Sumiko Higashi, amplified “televised images of war” by setting a new “precedent for grisly scenes” on film.63 We could add to this micro-genre the Arlo Guthrie album and Arthur Penn’s film Alice’s Restaurant (1967 and 1969), and Brian De Palma’s film Greetings (1968). Each of these works resorted to satire during a time of conflict as “the Vietnam War . . . proved so disturbing that it invited repression.”64 As related elsewhere, most notably by Rick Berg and David James, the Vietnam war was peculiar in that it failed to be “compatible” with forms of popular culture of the time.65 Of course innumerable fictional books, narrative films, documentaries, plays, and artworks addressed the war, and its repercussions, after the war’s end, but during the conflict itself we seldom see Vietnam explicitly depicted in the arts.

Outside the literary and dramatic arts, and in the realm of fine art, the Vietnam War was often addressed indirectly, through satire (as with Winogrand), allegory, or appropriation. Rosler, whom we have seen as a critic of both MoMA and Winogrand, created a series of collages entitled Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful between 1967 and 1972. The works appropriated imagery from House Beautiful magazine and juxtaposed them with graphic images from the popular press depicting violence in Vietnam. The stark contrasts within the images serve to remind the viewer of the distance between an insulated modern American lifestyle and the wars waged to preserve that lifestyle. Despite their serious and infuriated tenor, the images are strangely comical. Though choosing appropriation as an indirect means, as opposed to satire, the outcome is the same; to paraphrase Terry, the comedy redoubles the grave tone of the artist’s intent. In Winogrand’s social satire, Terry’s Viet Rock, and Rosler’s collages, the only appropriate social response to a war that was “unassimilable” by culture was to caricature reality. Of course, the risk of lampooning social conditions during a time of war is that such material may appear ambivalent.

Though Rosler would certainly hesitate to have her work placed in such a context with Winogrand’s, as she was critical of Winogrand’s compliance with Szarkowski’s curatorial program, seeing his satire as socially disengaged is a reading of the work tied only to its existence within a museum. Recall that according to Aulich, the success of the Q: And Babies? poster of the AWC was that MoMA failed to participate and thus appropriate the work.66 What Aulich implied was that the socially transformative potential of modern art could only be realized outside institutional constriction. Therefore, Winogrand’s book The Animals, and not the exhibition, might participate in such a socially engaged definition of modern art, because like Q: And Babies? it subverts “the dominant conventions of the art object and the market system.”67 That is, in lacking the singularity, authenticity, and thus connoisseurship one associates with fine-art objects, the photobook can circulate without the same cultural and social restrictions as a museum exhibition of photographs.

More accessible, more public, and thus more political, Winogrand’s The Animals should be understood in a tradition of American photography books invested in social commentary. Itis part of a genealogy of books, dating back to those produced during the Great Depression, which embrace the book form as

a means of social documentation coupled with persuasive politics. As noted by William Stott in Documentary Expression and Thirties America, the definitive book on the subject, published in 1973 in the shadow of the Vietnam War, the documentary photobook makes the reader feel that he or she is a “firsthand witness to a social condition.”68 Critical examples of the form are represented by Archibald MacLeish’s Land of the Free (1938), the Paul Taylor and Dorothea Lange collaboration An American Exodus (1939), and Margaret Bourke-White and the novelist Erskine Caldwell’s You Have Seen Their Faces (1937). Despite the redemptive, New Deal politics they promote, they share with Winogrand’s work a literary sensibility. MacLeish’s Land of the Free was “a book of photographs illustrated by a poem,” according to its author, while Taylor and Lange’s An American Exodus was a stark narrative of cross-country migration reaffirming the imagery in Steinbeck’s 1939 Grapes of Wrath. Bourke-White and Caldwell’s book, though, was unapologetically fictional; Caldwell fabricated quotes to use as captions, while Bourke-White concentrated on the tragic and abject, thus creating a hyperbolic image of the state of American society during the Depression. Modeled on critical precedents, such as Walker Evans’s American Photographs (1938) or Robert Frank’s The Americans (1959), with their personal stylizations of documentary photography, Winogrand’s The Animals presents the photobook as a literary form with an appropriate genre to suit—satire.69

The American War

“You can’t rationalize what you can do,” Haeberle said recently regarding a common reaction he has had to his photographs. 70 Why did he not intervene in the My Lai massacre? How could he have been a passive participant? Haeberle’s response is that, unless present in the moment, one cannot hypothesize a reaction. Though Haeberle’s reaction in the moment was one of photojournalistic intuition, his reaction to the color images after the fact appears to have been more calculated. As we have seen, Haeberle’s images selectively limit the appearance of soldiers, thus limiting culpability of those involved in the My Lai massacre. As he revealed in a 2009 interview with the Cleveland Plain Dealer (his “last interview”), Haeberle destroyed numerous color images taken with his Nikon.71 Though seventeen images were submitted to record for the army investigatory report, a typical roll of Ektachrome slide film in the late 1960s would have contained thirty-six exposures.72 At most, nineteen images were destroyed between the time Haeberle left active duty in March 1969 and initial visits to him by the Army’s Criminal Investigation Department in August 1969.73

Haeberle’s act of destruction has barely been commented on. David Quigg, writing for the Huffington Post, recently claimed that once Haeberle destroyed some of the color images, the remaining photographs no longer “qualif[ied] as journalism.”74 As we can now recognize, though, neither did the black-and-white images. They too were selectively made to meet the needs of the army’s internal reporting service. Haeberle’s act of self-editing, with both cameras, is fundamental to a cultural shift in the acceptance of photography as a surrogate for reality.

As Haeberle readily admitted, forty years after the fact, one cannot know the reality of an experience through a photograph of that experience. As viewers of the images, we cannot “rationalize” what our reactions to the events of March 16, 1968, might have been—we cannot know. In Haeberle’s words, “You don’t know. Until you’re in that reality. You never know.”75 If the photographer, the figure here who is deemed responsible for realizing these events for the public, is not convinced of the photograph’s communicative ability, can that event ever be present?

Given this perceived limitation in the media’s presentation of the war, that artists chose to represent the war indirectly (through appropriation, allegory, and satire) is telling. Even Haeberle participated in this logic of foregoing the photographic surrogate for a more personally expressive form. By editing, destroying, and sequencing his color images, Haeberle’s photographs of My Lai are not evidence but a construction of events that expresses a singular perspective. In this sense, Szarkowski’s New Documents thesis was prescient: the documentary photograph was no longer socially persuasive and public, but individualistic and always personal. As Stott made clear in Documentary Expression, documentary photography functions because of its human element; it is always “biased,” as we cannot take for granted the person behind the camera.76 Yet despite Szarkowski and Stott’s revision of “documentary photography” toward the personal, in the realm of the law (and as military photojournalism), Haeberle’s images were seen to imply no culpability on the photographer’s part. The responsibility rested primarily on Calley, a figure never pictured in Haeberle’s images. However, the turn to a public perception of documentary photography after My Lai that accepts the image as enmeshed in individualistic sensibility (central to Szarkowski’s modernization of photography) has led to a limitation of photography’s capability to insinuate guilt anywhere beyond the camera.77

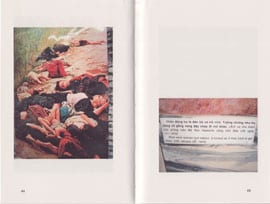

Despite the apotheosis of photography from socially persuasive function to individualistic expressive form at MoMA during the Vietnam era, I want to end by giving the museum a chance to be transformative and redemptive, and thus have a social impact. The example is not to be found at MoMA, nor in New York, but in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, at the War Remnants Museum. There we find Haeberle’s images again appropriated, by way of their reproduction in Life, and used to memorialize the massacre for the Vietnamese. In this context, the war is not the Vietnam War but the American War. Furthermore, the museum I am interested in is not the actual place, but its reduplication as a book: Harrell Fletcher’s 2005 The American War,which consists of the artist’s documentation of exhibits at the War Remnants Museum. The story told by Fletcher’s images of the museum is one often unrecognized in the United States. The American War finds torture, terror, atrocity, and lifelong malady as the war’s enduring legacy. Fletcher’s book is a simple gesture: it shares information by making photographs of photographs. As Fletcher readily admits, the images in the book are partial: “The museum and my re-presentations of it are only showing one perspective, there are many others.”78 In that sense, Fletcher’s project reminds us of the necessary role of photography in society: it provides different and personal perspectives onto the world. To recognize the photograph as a personal surrogate of reality (and not reality itself) is to recognize the photograph’s human element. The photograph is a place of empathy and connection between cultures, and Fletcher’s decision to realize the project in book form is critical.79 As a book, it circulates publicly and is absorbed privately. Thus, unlike an exhibition of photographs, the book of photographs may simultaneously affect personal and social understandings of war, reminding us not only of the public need for photography, but also that its effectiveness rests on interpersonal connections.

Chris Balaschak is an assistant professor of art history at Flagler College. His research focuses on the institutions and publications that cultivate definitions of documentary photography. He has recently completed a manuscript entitled “Bound: The Photobook and the Szarkowski Moment,” which considers how photography books helped to forge a photographic modernism. Balaschak is currently researching the redefinition of social documentary photography within contemporary art’s “social turn.”

- Garry Winogrand, interview with Barbaralee Diamonstein, in Visions and Images: American Photographers on Photography (New York: Rizzoli, 1982), 180. ↩

- David James, “Rock and Roll in Representations of the Invasion of Vietnam,” Representations 29 (Winter 1990): 79. ↩

- Lucy Lippard’s commentary on Leon Golub is key here. Included in her exhibition A Different War, Golub appropriated media imagery as a means of representation, and in that way his is typical of work Lippard presented in the exhibition. See Lucy Lippard, A Different War (Seattle: Real Comet Press, 1990). ↩

- As a consortium of artists, writers, and curators, the AWC coalesced around “13 Demands,” a letter calling for artists’ rights to the use and publication of their work, as well as the need for exhibitions that represented the racial and sexual diversity of modern artists. See Documents I (New York: Art Workers’ Coalition, 1969). ↩

- See “Ars Gratia Artis,” Newsweek, February 9, 1970, 80. The narrative of these events is also retold in Lippard, 26; in Lippard, Get the Message? A Decade of Art for Social Change (New York: Dutton, 1984); and in Julia Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009). ↩

- The Winogrand photograph is often dated 1970, but the event took place in 1969. An Associated Press photograph by J. Spencer Jones dated 1969 shows the same event. For another description of the event that dates it to 1969, see Ann Charters, “How to Maintain a Peaceful Demonstration,” in The Portable Sixties Reader, ed. Charters (New York: Penguin, 2003), 141–55. ↩

- The visual consonance between the images was first brought to my attention by Julia Bryan-Wilson while I was her teaching assistant at the University of California, Irvine, in spring 2010. ↩

- See Francis Frascina, “Meyer Schapiro’s Choices: My Lai, Guernica, MOMA and the Art Left, 1969–70,” Journal of Contemporary History 30, no. 3 (July 1995): 499. ↩

- See Lippard, Get the Message? 8–9. ↩

- The text was drawn from a November 24, 1969, interview between Mike Wallace and the soldier Paul Meadlo, discussing the victims of My Lai and his actions there. ↩

- See Mary Anne Staniszewski, The Power of Display: A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1988), 265. ↩

- James Aulich, “Vietnam, Fine Art, and the Culture Industry,” in Vietnam Images: War and Representation, ed. Jeffrey Walsh and Aulich (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989), 82. ↩

- Lippard, Get the Message? 8. ↩

- Lippard, A Different War, 17. ↩

- William Stott affirmed the historical genesis of documentary-style photography in 1973. when he wrote that a documentary photograph is at once “impersonal” and “human,” its human element allowing for a sympathetic appeal to the viewer which could become a vehicle for ideology. Stott, Documentary Expression and Thirties America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), 6. Sources critical to Stott include Edward Steichen, “The F.S.A. Photographers,” U.S. Camera 1939 (New York, 1938), 43–65; and Roy Stryker, “Documentary Photography,” The Complete Photographer (Chicago: National Education Alliance, 1942), 1364–66. ↩

- Szarkowski’s attendance is noted in “Ars Gratia Artis?” 80. For essays on Szarkowski’s broad influence, see Christopher Phillips, “The Judgment Seat of Photography,” October 22 (Fall 1982): 27–63; and Maren Stange, “Photography and the Institution: Szarkowski at the Modern,” Massachusetts Review 19, no. 4, “Photography” (Winter 1978): 693–709. ↩

- Winogrand’s work had previously been included in MoMA exhibitions such as Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man (1955), and Szarkowski’s The Photographer’s Eye (1964) and New Documents (1966). A 1968 article in Popular Photography claims Winogrand was interested in making the book; the claim predates the MoMA exhibition by a year. See Jonathan Brand, “Critics’ Choice,” Popular Photography 63, no. 6 (June 1968): 139. Winogrand also states his interest in the Diamonstein interview, 181. ↩

- See Tod Papageorge, introduction to Public Relations (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1977), 13; and Carl Chiarenza, “Standing on the Corner . . . Reflections upon Winogrand’s Photographic Gaze: Mirror of Self or World,” Image 34, nos. 3–4 (Fall–Winter 1991): 50. ↩

- For a sense of the popularity of aping animalism at the time, consider a few cultural artifacts: the film Planet of the Apes (1968, dir. Franklin J. Schaeffer); Jane Goodall’s book My Friends the Wild Chimpanzees (Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 1969); and Desmond Morris’s urban sociology The Human Zoo (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1969). Szarkowski noted that The Animals “was printed in gravure in an edition of 30,000 copies, to sell at $2.50, and was a resounding commercial failure.” Szarkowski, The Work of Garry Winogrand (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1988), 22. ↩

- The iconographic resemblance is pointed out in Diamonstein,182, but denied in the same interview by Winogrand: “That has nothing to do with what I’m talking about now. It’s just that I carry an arm around with me, you know. I wouldn’t be caught dead without an arm.” A further connection between Renaissance humanism and Vietnam-era satire occurs in the 1970 film version of M*A*S*H, wherein Robert Altman stages a military meal as Da Vinci’s Last Supper. ↩

- Here I am invoking the sense of “civilization” preferred by Sigmund Freud to imply the rationalization of the human animal at the dawn of its socialization. See Freud, Civilization and its Discontents, trans. James Strachey (New York: Norton, 1961). ↩

- John Szarkowski, untitled essay in The Animals (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1969), n.p. ↩

- In a press release for the exhibition, Szarkowski explained that a “new generation of photographers has redirected the technique and aesthetic of documentary photography to more personal ends. Their aim has been not to reform life but to know it, not to persuade but to understand.” Museum of Modern Art, “New Documents, February 28–May 7, 1967” press release, February, 28 1967. ↩

- John Szarkowski, Mirrors and Windows: American Photography since 1960 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1978), 13. ↩

- Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Dell Publishing, 1978), 43. Sontag further notes, “What happens to people’s feelings on first exposure to today’s neighborhood pornographic film, or to tonight’s televised atrocity is not so different from what happens when they first look at Arbus’s photographs. The photographs make a compassionate response feel irrelevant.” This view fed Sontag’s larger thesis that “photography is essentially an act of non-intervention.” Instead of evoking empathy, she claimed, photographs evoke “the feeling of being exempt from calamity.” Sontag, 41, 11, 168. Sontag’s thinking on the role of photography continued to evolve; see Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), esp. 121; and “Regarding the Torture of Others,” New York Times Magazine, May 23, 2004.” ↩

- Martha Rosler, “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography),” rep. The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography, ed. Richard Bolton (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), 321. ↩

- Ibid., 320. ↩

- Winogrand’s many photographs of political events of the period include “Peace Protest” (1970), “Women’s Liberation March” (1971), “Hard Hat Rally” (1969), and “Peace Demonstration.” (1969). ↩

- Szarkowski quoted in Stange, 697–98. Szarkowski’s allusions to a naturalist continued in a later interview, where he says about photography, “I am interested in the entire, indivisible, hairy beast—because in the real world, where photographs are made, these subspecies, or races, interbreed shamelessly and continually.” Mark Durden, “Eyes Wide Open: Interview with John Szarkowski,” Art in America 94, no. 5 (May 2006): 85. ↩

- Winogrand said, “There’s an arbitrary idea that the horizontal edge in a frame has to be the point of reference. And if you study those pictures, you’ll see I use the vertical often enough. I use either edge.” Diamonstein, 182. Carl Chiarenza also noted, “Content overwhelms form in this book as well. Winogrand’s vertical stabilizer holds the tilt or diagonal, and thus joins the play of content in some pictures.” Chiarenza, 50. Winogrand added to these thoughts in 1979: “What tilt? There’s only a tilt if you believe that the horizon line must be parallel to the horizontal edge. That’s arbitrary. In my pictures there’s always something parallel to the horizontal edge and that rationalizes the photograph.” “Q and A: Garry Winogrand,” American Photographer 2, no. 5 (May 1979): 55. ↩

- Szarkowski, The Work of Garry Winogrand, 26. ↩

- Ibid., 12. ↩

- Ibid., 12, 18, 15. ↩

- As A. D. Coleman wrote, from Winogrand’s “early work—up through The Animals . . . [one ↩

- Jonathan Green, American Photography: A Critical History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1984) 112. See Garry Winogrand, “Winogrand on Women,” in Women Are Beautiful (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1975). Carl Chiarenza writes, “Winogrand’s pictures are direct evidence of a patriarchal society, a society that forced women to aspire to a model formed long ago and continuously reinforced since.” Chiarenza, 28. ↩

- Szarkowski, The Work of Garry Winogrand, 22, 21. ↩

- See Report of the Department of the Army Review of the Preliminary Investigations into the My Lai Incident [“Peers Inquiry” ↩

- Ibid., vol. 2, book 11: Haeberle, 68. ↩

- Ibid., 67. ↩

- Though inscribed with the dates March 14, 1970 (when the inquiry was finalized), the volumes were first published in 1974. ↩

- See Michael Bilton and Kevin Sim, Four Hours in My Lai (New York: Penguin, 1992), 104. ↩

- Haeberle quoted in ibid., 124. ↩

- Report of the Department of the Army, vol. 3, book 6, is available as a PDF at www.loc.gov/rr/frd/Military_Law/pdf/RDAR-Vol-IIIBook6.pdf (as of November 8, 2012). The book contains all the images to which I refer by exhibition number, e.g., P-1. ↩

- Scenes similar to these are repeated in P-66 and P-67, where Sergeant Phu, another translator, is pictured interacting with locals. ↩

- The army held no claim and had no restrictions on servicemen using personal cameras during combat. Even when army investigators learned of these images, Haeberle held copyright and required the army to return the images. As Haeberle testified, they were used for “a series of illustrated talks about the war to various groups in Ohio.” Bilton and Sim, 241. ↩

- Report of the Department of the Army, vol. 2, book 11: Haeberle, 46. ↩

- Ibid., 53. ↩

- See James S. Olson and Randy Roberts, My Lai: A Brief History with Documents (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1998), 146–51; and Bilton and Sim, 218–19. ↩

- See Report of the Department of the Army, vol. 2, book 14: Stonich, 35. Such a violation is outlined clearly in the Fourth Geneva Convention, Section III, Article 53, “Destruction of Property”: “Any destruction by the Occupying Power of real or personal property belonging individually or collectively to private persons, or to the State, or to other public authorities, or to social or cooperative organizations, is prohibited, except where such destruction is rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.”

↩ - Report of the Department of the Army, vol. 2, book 11: Haeberle, 39. ↩

- Ibid., book 14: Stonich, 1, 42. See also vol. 2, book 14: Roberts, 99, 101. ↩

- Ibid., vol. 2, book 11: Haeberle, 71. ↩

- Phillip Knightley, “Vietnam 1954–1975,” in The American Experience in Vietnam: A Reader, ed. Gracy Sevy (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989), 129. ↩

- Calley quoted in Bilton and Sim, 21. ↩

- Kregg P. Jorgenson, Very Crazy G.I.!: Strange but True Stories of the Vietnam War (New York: Ballantine Books, 2001), 33–36. ↩

- Olson quoted in Bilton and Sim, 93. ↩

- Quoted in Olson and Roberts, 135. ↩

- Chris Philo and Chris Wilbert, “Animal Spaces, Beastly Places,” in Animal Spaces, Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human-Animal Relations, ed. Philo and Wilbert (London: Routledge, 2000), 13. Also of note in this book is Gail Davies, “Virtual Animals in Electronic Zoos: The Changing Geographies of Animal Capture and Display,” 243–66. Regarding colonialism and zoos, see Donna Haraway, Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science (London: Routledge, 1990). ↩

- Green, 112. ↩

- Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, The Park and the People: A History of Central Park (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998), 342, 344. ↩

- Each of these works, of course, owes something to George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945). ↩

- Megan Terry and Peter L. Friedman, “Viet Rock,” Tulane Drama Review 11, no. 1 (Autumn 1966): 197. ↩

- Sumiko Higashi, “Night of the Living Dead: A Horror Film about the Horrors of the Vietnam Era,” in From Hanoi to Hollywood: The Vietnam War in American Film, ed. Linda Dittmar and Gene Michaud (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2000), 184. ↩

- Ibid., 186. ↩

- James, 83. ↩

- Aulich, 82. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Stott, 214. ↩

- Winogrand professed his admiration for Frank and Evans. See Charles Hagen, “An Interview with Garry Winogrand,” Afterimage, December 1977, 14; and “Monkeys Make the Problem More Difficult: A Collective Interview with Garry Winogrand,” Image 15, no. 2 (July 1972):3–4. The connections between Winogrand and Frank and Evans are also discussed in Chiarenza, 19, 27. ↩

- Haeberle quoted in David I. Andersen, “Photographer Remembers My Lai Massacre,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 19, 2009. For video, see http://videos.cleveland.com/plain-dealer/2009/11/photographer_remembers_my_lai.html (as of November 2, 2011). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- See Evelyn Theiss, “My Lai Photographer Ron Haeberle Admits He Destroyed Pictures of Soldiers in the Act of Killing,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 20, 2009, at http://blog.cleveland.com/pdextra/2009/11/post_25.html (as of November 2, 2011). ↩

- See Anderson interview. ↩

- David Quigg, “Part Exposé, Part Cover-Up: 1968’s My Lai Massacre Photos Have Big Lessons for Citizen Journalists,” Huffington Post, November 24, 2009, at www.huffingtonpost.com/david-quigg/part-expos-part-cover-up_b_368685.html (as of November 2, 2011). ↩

- Haeberle quoted in Anderson interview. ↩

- Stott, 61. ↩

- Following suit, an individual photographer’s relation to the scene photographed has turned out not to implicate those overseeing the atrocity pictured, but primarily those captured by the camera. Consider the photographs taken at Abu Ghraib, where those pictured (Lynndie England, Charles Graner, Ivan Frederick, and Sabrina Harman) and the persons behind the camera (Harman and Frederick in particular) took the brunt of public blame. ↩

- Harrell Fletcher, The American War (Atlanta: J&L Books, 2007); excerpts are online at www.harrellfletcher.com/theamericanwar/ (as of November 9, 2011). ↩

- The American War also existed as an exhibition that toured the United States 2005–7. I first saw the project during its run at LAX-ART in Los Angeles, January 30–March 3, 2007. ↩