From Art Journal 75, no. 3 (Fall 2016)

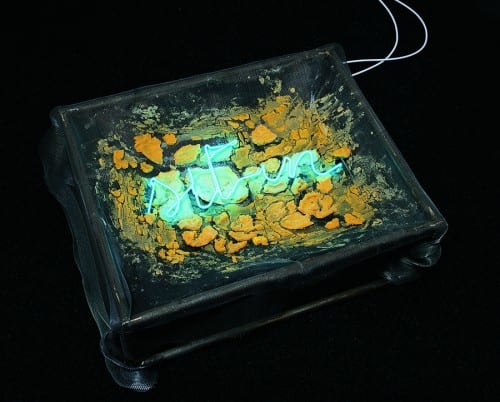

In 1968, while demonstrating students occupied university buildings less than a mile away, the Italian artist Mario Merz hung a handful of neon lights bent into the numerals 1, 1, 2, 3, and 5 above the kitchen stove in his home on Via Santa Giulia in Turin. It wasn’t yet an artwork, just something to think about in the place where he and his wife, fellow artist Marisa Merz, gathered to talk with each other and with friends. For the previous two years, Mario Merz had been experimenting with neon tubes, using various lengths of them to slice through a painted canvas or to penetrate household objects. In January 1968 such seemingly eclectic experiments with materials, light, and form had brought the forty-three-year-old former informel painter into dialogue with the younger sculptors whose work was beginning to be called Arte Povera.1 Merz also began “writing” with neon that year, appropriating phrases from current international conflicts—from Turin, to Paris, to Hanoi. Despite these apparent forays into topical politics, much of the literature on Merz considers his art as oriented toward personal and poetic objectives that overshadow any social and political ends. Rereading the appropriated text works and experiments with neon numbers of 1968 in the context of contemporaneous Italian sociopolitical philosophy, however, brings Merz’s entire artistic project into new focus, foregrounding his interest in the irreducible relationship between the individual and society.

The neon numerals hanging on the same kitchen pegs as a can opener, a ladle, and a measuring cup may not have seemed like a radical gesture, compared with what was going on outside the walls, but they form the theoretical foundation on which political engagement can be read in Merz’s art. The numbers 1, 1, 2, 3, and 5 are the first five ordinals of the infinitely expanding Fibonacci sequence, a medieval counting system once posited to reveal a divine order in nature.2 Together these digits compose the minimum expression of the mathematical operation, which would become a lasting trademark of Merz’s artwork. Their relatively increasing distances from one another indicate the first systematic application of this operation to the evaluation of a social space. Between 1968, when he began showing in the Arte Povera context with his neon works, and 1970, and when he first exhibited works using Fibonacci numbers, Merz was experimenting with direct and indirect ways of connecting his art to his political ideals, in material and formal terms.3 At the same time, the most progressive political theorists in Italy were developing new ways of looking at the old issues of labor and class struggle, known after 1973 as Autonomia Organizzata (Organized Autonomy). When read in the context of this political theory, as well as in a continuum with Merz’s other artworks of this period, the Fibonacci works mark a shift in his practice from displaying topically political messages to engaging with the complex relationship between the individual and the social, more abstractly.

In the copious literature on Merz’s art, consisting mostly of exhibition reviews and catalogue essays, the Fibonacci numbers have been interpreted in a variety of ways: from providing “a metaphor of the universe,” to broadly denoting “all forms of progression,” to symbolizing the “life flow in existentially sympathetic things and living beings.”4 Within a body of critical literature that regularly refers to the artist as a shaman, a nomad, or even a “mythomaniac,” the accumulation of such expansive claims results in an overwhelmingly romantic sense that Merz’s art aims to reimagine a prelapsarian relationship between humans and the natural world.5 This prevailing vein of interpretation is in keeping with a larger tendency to read Arte Povera in general as a back-to-nature riposte to American Minimalism, one that discounts the way these artists’ practices are, among other things, rooted in their own distinct sociopolitical context. In the wake of a resurgent interest in Arte Povera, such reactionary “poor materials” interpretations are beginning to give way to more nuanced analyses of the art and artists in their specific and varied contexts.6 The present essay proposes that, between 1968 and 1972, Merz developed methods that gave form to ideas and tactics consonant with the emergent theories of Autonomia, a political theory and a decentered social movement that grew from the Marxist-influenced Italian workerism (“operaismo”) of the 1950s and was shaped by the protest movements of the late 1960s. In opposition to the traditional, rigid organization of labor into unions, however, Autonomia’s character has been described as “the body without organs of politics, anti-hierarchic, anti-dialectic, anti-representative.”7 That is, its many forms operated independently, in order to destabilize multiple aspects of socioeconomic and political relations, simultaneously. Merz’s deployment of multivalent materials and text will be shown here to parallel the structure of the Autonomist movement and its central concepts. Read through this lens, Merz’s use of language, material, and, especially, anachronistic systems like the Fibonacci numbers speaks to the complex interdependence of the individual and the collective, which Autonomia took as its primary theoretical position in the 1970s.8

From Guerilla to Nomad . . . to Autonomist?

Identifying the emergence of this focus in Merz’s 1968 works and recontextualizing the subsequent prominence of the Fibonacci series in his post-1970 oeuvre provide an important rebuttal to the dominant portrayal of the artist as a wandering bohemian. With fluctuating degrees of political connotation, the Italian critic and curator Germano Celant, who first coined “Arte Povera,” consistently deploys the image of the artist-as-nomad in his writings on Arte Povera, and especially in regard to Merz.9 Celant’s first argument for Arte Povera’s relevance connected it to the sociopolitical conditions of the day. Setting forth his ideas in the style of a manifesto, he likened the artist to a guerilla warrior who “rejects all labels and identifies solely with himself.”10 Two years later, in the first book on this art, Celant argued that Arte Povera artists actively destroy their social role and seek freedom in nomadic behavior.11 In Celant’s early writings, these concepts—guerilla and nomad—appear to be united by the notion of radical individuality. Moreover, each implies the flexibility and mobility of working outside, if not against, “the system,” which was part of a larger political discourse in late 1960s Italy.

Celant’s characterization of the guerilla/nomad artist, who chooses to escape the hierarchical systems of art and the tyranny of its economy in order to pursue acts of presentation rather than representation, is strikingly analogous to Autonomia’s espousal of “autonomy” through self-valorization and a strategy of refusal.12 In Celant’s 1969 essay on Arte Povera, the critic distinctly uses the term “autonomy,” in quotes, to describe the Arte Povera artist, who he argues wants to “possess above all the ‘autonomy’ of his own identity.”13 Later, in a 1979 essay on Merz’s art, Celant compares contemporary artists to “nomads or vagabonds” who remain on the fringes of society, in terms that evoke the contemporaneous writings of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, both of whom were closely allied to the protagonists of Autonomia.14 For instance, when Celant writes that Merz “is similar to a nomad who chooses the location of his campsite in order to draw upon the territory for economic resources and cultural stimuli,” it recalls Deleuze and Guattari’s description of the nomad as an intermezzo, an autonomous agent who lives outside the state, but on its territory.15 Deleuze and Guattari notably link this concept to the political theorist Mario Tronti, whose writings form the early foundations of autonomous theory.16 However, Celant’s specific formulation of the nomad as someone who “draws upon the territory for economic resources” effectively (if unwittingly) positions the artist as fickle and parasitic, a notion that is particularly problematic in regard to Merz, who was, arguably, the most politically experienced of the Arte Povera artists.17 The concept of the nomad is further diluted, and further distanced from that of the guerrilla warrior, when it is picked up and echoed in the later writings of critics and curators like Harald Szeemann, who in 1990 called Merz a “solitary wandering visionary,” or Danilo Eccher, who in 1995 described Merz’s art as representing a “libertarian individualism.”18

From the end of the 1970s onward, as such nomadic individualism in the literature on Merz becomes ever more radically divorced from its earlier political connotations, a series of questions emerge about its use. First, why does Celant move from guerilla to nomad in his writings? Was it politically unpalatable, or even dangerous, to label the artist as guerrilla in 1979? The years 1968–78—known in Italy as the anni di piombo, or “years of lead”—were marked by acts of domestic terrorism carried out by radicalized, violent fringes of 1960s social movements on both extremes of the political spectrum.19 The most notorious of these was the 1978 kidnapping and execution of the former prime minister of Italy, Aldo Moro, which was attributed to a terrorist group known as the Brigate Rosse, or Red Brigades. In the aftermath of this crisis, the Italian government persecuted left-leaning intellectuals and labor organizers, accusing many of secret involvement with the Red Brigades. In April of 1979, many of the writers associated with Autonomia—Antonio (Toni) Negri, Francesco Piperno, Oreste Scalzone, and others—were arrested and imprisoned.20 In that climate, was a “guerrilla artist” at risk of being caught in the same paranoid net? Or is the answer more banal? Celant’s later, lighter description of the “artist as nomad” links the formal codes of the artist’s igloos with the primitivizing image of the bohemian artist resurgent in the works of Transavanguardia, a new generation of Italian artists championed by rival curator Achille Bonito-Oliva.

Whatever the reason, it is clear that the term “nomad” becomes too blunt an object in the hands of later curators and critics, its romantic connotations overshadowing any earlier embodiment of Autonomist ideals. The challenge, now, is to review that period with historical remove, and to identify the relationships among Merz’s art, its reception, and the theories of Autonomia. For example, did Merz’s friendship with Manfredo Massironi, an Op artist responsible for the visual design of the radical magazine Classe operaia (Working Class), mean that Merz was reading the writings of its founders Tronti and Negri?21 Gian Enzo Sperone’s gallery, where Merz had a breakout solo show of neon-pierced objects in January 1968, shared a building with Adriano Sofri’s extra-parliamentary group Lotta Continua in 1969. Did they share more than an address? Sperone claims that the leftist organizers had little patience for the art next door, leaving warnings and slogans outside the gallery door to protest its sponsorship of American Minimalist and Pop artists, whose works were read as an extension of capitalist imperialism.22 In the throes of the political movement, some have argued that contemporary art was most useful to the cause when it could illustrate pamphlets or be sold for cash to support other activities.23 Looking back, how can we understand Merz’s work as connected to the radical politics of this era, when the radicals themselves seemed to have little regard for such art? It is only by looking at the structure of Merz’s works from this period, in concert with theoretical texts of Autonomia itself, that the paradox between individualism and collectivism comes into clear view as one of the primary theoretical paradigms of the era in which both the mature artist and the political theory emerged.

The One and the Many: Language and Material

Between April and June of 1968, Merz exhibited two distinct types of assemblages using language written in neon, in ways that appear to directly and topically engage the sociopolitical context. The first of these, exhibited in April at Percorso in Rome, was Igloo di Giap (Giap’s Igloo, 1968), made of bags of clay hung on a metal armature, overwritten in neon by a phrase attributed to the North Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap.24 Here Merz chose a phrase that models a tactical impasse: “Se il nemico si concentra perde terreno, se si disperde perde forza” (If the enemy masses, he loses ground, if he scatters, he loses strength). Moreover, the composition of Giap’s Igloo mirrors the sentiment of the dictum.25 The individual bags of clay combine to provide structure, shelter, and warmth for an individual inhabitant, yet when amassed for this purpose, they lose the potential for flexibility and mobility, and certainly the clay does not cover as much ground as if it were spread out on the earth. In a 1971 interview with Celant, Merz recalled that when he first read the phrase, it altered his view to something as “absolute” as war:

It was not the idea of the enemy as somebody whom one must move against; rather, the idea of the enemy in a dialectical situation that involves the person reading the words. This was very important for me: the idea of strength in an absolute sense was removed from strength itself. Strength became a dialectical quality in relation to the individual himself.26

Seen this way, it is clear that Merz’s first igloo was neither a simple reference to a primitive or vagabond lifestyle, nor is the text element merely a topical reference to the war in Vietnam.27 Instead, the artist’s meticulous use of materials and language in works such as Giap’s Igloo reflects his early research into a codependency between individual vitality and the structural strength of alliance.

the author)

In June, on the heels of the student and worker demonstrations in Paris and the boycott of the Venice Biennale, Merz showed this igloo again in a group show at Turin’s Deposito D’Arte Presente, or DDP.28 Here he also included for the first time an igloo with the phrase “Objet cache-toi” (Object, Conceal Yourself, 1968), borrowing an anonymous graffito written in Paris that spring. Alongside these igloos, Merz showed two more new works using neon in a second way: as phrases set onto beds of beeswax. Solitario solidale (Solitary solidary) also bears appropriated political graffiti from Paris, and Sit-In references a form of nonviolent demonstration favored by students at the Sorbonne and at the University of Turin.29 In all four objects, the prominence of linguistic referents, both visually and in the titles of the works, makes them seem straightforwardly activist. The Italian curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, however, has argued that Merz’s use of words can be read more poetically than politically, in relation to the position of the viewer’s body and the context in which they are read.30 She shows how a work like Giap’s Igloo requires the viewer’s corporeal movement in order to read the phrase about the dispersion of bodies, and how Sit-In enacts the eponymous phrase as the warm neon letters melt away the solid wax. Building on such assessments that complicate easy readings of direct political sentiment, I argue that Merz negotiates between poetic individual meaning and sociopolitical significance. Further, reading Merz’s tactical deployment of language through the lens of Autonomist theory reveals the works’ subtle politicization and provides a structural logic that emerges through the twinned concepts of individuality and solidarity.

Giap’s Igloo and Object, Conceal Yourself are perhaps the most discussed of these 1968 objects, as the first examples of the igloos that would become one of Merz’s signature artistic forms.31 They also appear to reference politics more directly than the later igloos and so seem an obvious choice for an argument about recognizing the politics in Merz’s work of this period. However, Solitary solidary is the most significant of these 1968 assemblages for the way it succinctly demonstrates the interdependence of individual engagement and collective responsibility in art as in society, although it is far less discussed in the critical literature on Merz.32 called one of his works Solitario solidale, confirmed in his universal solitude.” Szeeman, 104.] Made of beeswax, neon, and a fish-cooking pot, Solitary solidary reproduces a revolutionary Parisian graffito, which itself refers to Albert Camus’s 1957 short story “The Artist at Work,” a fact likely known by the well-read Merz.33 In Camus’s text, a painter falls victim to his own success, begins to doubt his art, and destroys all of the work he had previously completed, angering dealers and estranging himself from friends and family. The artist-protagonist then embarks on a new work, which he pursues to the point of mental and physical exhaustion. Finally, he collapses, and, at the climax of the story, his ultimate canvas is revealed to contain a single illegible word, reading either “solitary” or “solidary.”34 In the end, no one is able to determine which of these two words it is, leaving the painting’s viewers, and Camus’s readers, suspended between the opposed meanings of togetherness and isolation. Evocatively, the painter’s wife finds hope in the work’s indecipherability.

Camus’s story has been interpreted as a commentary on the impossible resolution between the mental space (or separation) necessary to be an artist, and the social and material demands the artist must simultaneously negotiate moving though the world. Looking at the terms more closely in the context of 1968, a more particular and subtly politicized reading emerges. Merz explained that the enigmatic phrase “Solitaire solidaire” had fascinated him when he saw it scrawled on the walls of the Sorbonne, because the conflicting adjectives came so close to linguistic elision.35 (That is, in French, as in English, the words are differentiated by only one consonant.) Stalled in a dialectical opposition, these terms present a paradox: the conditions they describe appear to be at odds, yet each idea is, by opposite definition, dependent on the other. The sentiment of this tautological riddle, when read in the context of its appropriation by the student movement, is echoed in Herbert Marcuse’s nearly contemporaneous critique of Marxism. Marcuse famously quipped that “solidarity would be on weak grounds were it not rooted in the instinctual structure of individuals.”36 With this in mind, reading the words together as a phrase suggests that the project of communal solidarity—witnessed by Merz in Turin and in Paris in the late 1960s—must be seen to start “solitarily” within each individual. Merz’s use of this enigmatic phrase demonstrates not only that he was following the local and international student movements with interest, but, more speculatively, that he regarded the notion of an artist’s work as caught between the extremes of individual intellectual interest and broader social relevance to be as pressing an issue in 1968 as it had been a decade earlier for Camus. If one hides away in the studio as Camus’s protagonist did, what purpose can unseen art hold? Alternately, how can the artist maintain the independence necessary for a critical practice within the emergent “machine” of the art world, or when entering into the political pageantry of the piazza?

The form and composition of Solitary solidary further explore these dilemmas, modeling the paradoxical interdependence of individual action and collective strength through Merz’s specific material choices. Beeswax, which begins to appear in a number of Merz’s works from this period, is the base of the sculpture.37 and his work.” Braun, 4.] Aside from its formal advantages—a pleasing scent, a golden hue, and easy malleability—beeswax presents allegorical possibilities inherent in its own material history. That is, beeswax is the product of a group of individual worker bees essential to the complex social structure of a colony’s hive. While each of these workers is highly skilled at her task, no individual honeybee can survive without the support of a colony, and the colony relies on each bee working for the good of the collective.38 As the material, if not sculptural, product of this division of labor, beeswax thus offers a material metonym of the relationship between individual and cooperative work. In the literature on the social structures of bee populations, the complex problem-solving collectively achieved by bees is described in socially radical democratic terms. From necessary daily tasks like foraging, honey and wax production, and brood rearing, to the vital annual process of selecting a new hive, bees work together to achieve goals. The animal behaviorist Thomas Seeley argues that despite the language used to describe her, the queen bee is not the boss of the workers: “The work of a hive is instead governed collectively by the workers themselves, each one an alert individual making tours of inspection looking for things to do and acting on her own to serve the community.”39 As one product of this collective labor, beeswax in Merz’s work can be read as indicating the natural equilibrium between the individual task and communal survival that Seeley describes.

Merz’s choice of material, which bees use for sculpting the critical structure of their social space, is even more clearly evocative of contemporaneous political theory when read in the context of Sylvère Lotringer and Christian Marazzi’s paradoxical description of Autonomy as “a way of acting collectively.”40 Autonomia thus conceived proposes a structural equilibrium not unlike that of the beehive, a natural model of the body without organs. In Merz’s Solitary solidary, the beeswax functions as a strategic backdrop for the artist’s own exploration of the complex relationship between individuality and community, one which is further articulated through the enigmatic neon phrase sitting above it.

The neon itself, which illuminates the paradoxical titular phrase, also evokes the interdependence of the one and the many, since what appears to be a solid beam of light is actually made by a mass of electrically charged individual gas molecules. As much as they provide light, neon and other fluorescent gases can be seen as visually indicative of the activation of innumerable individual particles.41 Further, neon had a specific cultural association in postwar Italy with the artist Lucio Fontana, who famously used it to create a ceiling installation for Italia ’61, the world expo of labor held that year in Turin. Fontana had previously installed neon overhead at the ninth Milan Triennale of design in 1951. In Milan, the tubes formed a gestural arabesque that hung over the central staircase. For the Turin labor expo, however, Fontana refined his approach, demarcating space with a gridded ceiling of neon tubes that read as a spatial environment more than an object. This development is significant in that it creates an abstraction from an industrial material, and it indicates the direction of Fontana’s artistic research into the creation of ambient spaces rather than distinct art objects. When Merz began to use neon as text in 1968, he furthered a perceptive push-pull between the immaterial light and the physical tubes by turning language—an intangible vehicle of meaning—into a physical object. Merz thus availed himself of neon’s potent metaphorical possibilities: the one and the many, a visible demonstration of collective energy, and the transparency of language made concrete.

Solitary solidary’s conceptual tension—first produced by the phrase and echoed in the formal aspects of the work—clearly uses the suspension of meaning as a critical tactic. This can also be seen as a political approach that goes beyond a linguistic communication. The means by which Solitary solidary allows the viewer to explore the complex negotiations between the individual and social—through material resonances, visual cues, and semiotic play—are also expressed in the methodology of self-valorization found in the political theories of Autonomia, especially in the period writings of Negri. A political philosopher, Negri was the founding editor of the magazines Quaderni Rossi (Red Notebooks) and Classe Operaia (Working Class), as well as a founder of the labor movement Potere Operaio (Worker Power). Throughout the 1960s and 1970s he wrote essays and published pamphlets in which he argued for a revolutionary consciousness of separateness, refuting the very structure of the worn-out dialectic between the worker and the capitalist. In his 1977 text “Domino e Sabotaggio” (Domination and Sabotage), for example, Negri wrote that such separation was a necessary part of the movement: “Working class self-valorization is first and foremost de-structuration of the enemy totality, taken to a point of exclusivity in the self-recognition of the class’s collective independence.” “Collective independence” is a key phrase here, since by this term he argues that he does not see the goal as a future all-embracing recomposition, but instead “as a moment of intensive rooting within my own separateness. I am other—as is the movement of that collective praxis within which I move.”42 The conflation of separateness and collectivity is vital to the autonomist project and codified in its very name. Indeed, while its name is often shortened to Autonomia, the full title given by Negri is Autonomia Organizzata, or organized autonomy.

The arguments of writers like Negri—that autonomy is a kind of collective independence—are tactically parallel to Merz’s neon text works of 1968, not only in their formal and linguistic significance (beeswax/neon and poetic/political text), but also in the way the object is encountered and adjudicated by the viewer. Just as Negri contends that only through a process of self-valorization can the worker break free of the stale dialectic between the laboring classes and the capitalist classes, the meaning of a work like Solitary solidary must similarly be negotiated and determined by each viewer-reader, separately. In the artwork, signification is a process that plays out between the artwork as a material object in the larger world and the internal consciousness of the subject. In this sense, the polyvalence of this approach must be seen as not just topical, but profoundly political, since it reinforces the centrality of each individual viewer to the collective effectiveness of the work.

Che fare? What Is the Artist to Do?

A third neon-and-wax work from the same year further manifests Merz’s understanding of the artist’s social role in ways that parallel the new political theories of Autonomia. Critics regularly read the piece Che fare?—made in neon and wax in 1968, and reprised in rubber letters on a Roman gallery wall in 1969—as borrowing a phrase directly from Vladimir Lenin’s well-known 1902 polemic, “Chto Delat?” (What Is to Be Done?), which sketched a revolutionary direction for Bolshevik Marxism.43 Perhaps, as demonstrated in Solitary solidary, Merz was here actively negotiating his role as an artist vis-à-vis politics. Certainly the neon phrase seemed apt in the late 1960s, when another generation of students and workers aimed at revolution.44 Lenin’s own referent, however, was both political and artistic, pointing as it did to a popular 1863 novel written clandestinely by the Russian author Nicolay Chernyshevsky, which featured characters living a communal, unstructured life.45 Not only does this connect thematically to the changes in Italian society in the 1960–70s, but if one considers Merz’s iteration a reference to Chernyshevsky’s story, the work could also be read to signify the precariousness of artistic freedom, since the story was written while the Russian author was imprisoned by the tsar.46

Merz’s 1968 enunciation of the multivalent and historically laden phrase Che fare? displays an indeterminacy and flexibility that is as important as its august political lineage. In fact, the phrase might also refer to a text that was well-circulated in postwar Italy: Ignazio Silone’s Fontamara.47 Silone wrote the anti-Fascist novel, about the rising political consciousness of southern peasants, while in exile in 1933. The drama is set in an Abruzzian town and centers on the repeated encounters between the peasant Berardo and an unknown man who is described as having the demeanor of a student or a worker. Both characters are eventually jailed on suspicion of possessing anti-Fascist printed material, as Merz himself was in the 1940s.48 This parallelism underscores both Silone’s and Merz’s understandings of the political power of language. In the end, the peasants’ political awakening is signified by the publication of a newspaper titled Che fare?, which is itself the answer to the question—they must not only become conscious individually, they must each work to raise the consciousness of others through such vehicles of communication or dissemination. It bears mention here that Merz himself began to use bundles of newspapers in concert with Fibonacci numbers in his works of the 1970s.49 As the Italian scholar Judy Rawson has argued, the newspaper symbolizes the peasants changing from their mentality of “minding their own business” and beginning to consider the larger issues plaguing 1930s Italy.50 That is, each individual had to recognize the need to work toward collective change.

Does Merz’s work reference Silone’s novel, which only appeared in Italy after World War II, or the artist’s own experience of activism through pamphleteering? Does it recall Chernyshevsky’s revolutionary novel of the 1860s, or does it aim squarely at the new struggles of the late 1960s, when the phrase was gath-ering new currency in Milanese intellectual and creative circles? Che fare was, in fact, the title of a radical publication based in Milan in the late 1960s and 1970s that attempted to bring political theory and culture together. Beginning in May 1967, the journal published multilingual, collectively authored editorials on the politicization of art and literature in the wake of their postwar commercializa-tion.51 Direct crossover between early Autonomist politics and the journal’s commitment to the role of culture in these struggles can be seen in the Winter 1968–69 issue, titled “L’Autorganizzazione” (Self-Organization), in which the international events of 1968 were reported from diverse perspectives. Among the pages are images of the Atelier Populaire in Paris, an account of the artists’ protests of the Triennale di Milano, and stories about the student/worker occupation of the Biennale di Venezia, as well as a text by one of the leaders of the student movement in Bologna throughout the 1970s, Franco “Bifo” Berardi, whose essay begins with an analysis of the Leninist problem of organization posed by the eponymous phrase.52 Berardi argues that in the light of the new context, the answer to “what is to be done?” is that one must abandon the old theories of organization proposed by the revolutionary vanguard in favor of a minoritarian position that creates permanent turmoil, pushing the action, without trying to direct it.53

Berardi’s sentiment is apt for understanding the role of the artist enunciated by Merz’s Che fare?. The question is made physically present for the viewer, yet it contains so many referential layers—it offers so many ways into the work—that the viewer has to negotiate the direction herself. As with his other works from 1968, the artist inserts a provocation, whether it is a beam of light that interrupts the wholeness of an object or a tautological phrase that disrupts logical thinking. The conceptual wrestling required of the viewer to engage with the work constitutes a new way of being a viewer, just as autonomist strategies of self-valorization created new forms of organization and new social spaces. Whether or not Merz had ever heard of this journal, or had ever read anything written by Berardi/Bifo, their shared strategies of disruption were soon recognized. When the latter published a chronology of the Autonomist movement in 1980, it was illustrated by a photo of Merz’s installation Tables for 34 persons (1974–75), installed in an abandoned factory in Stuttgart.54

Systematic Thinking outside “the System”: The Fibonacci Numbers

Merz had, in fact, identified a number of ways to express his interest in the artist’s social role and his attraction to the paradox of individualism and solidarity in 1968, including the installation of the first five Fibonacci numbers on his kitchen wall. That is, the Fibonacci sequence only works on the basis of each individual number “scaffolding” or forming a foundation for the others. The numbers are both abstract and personified by the links to other numbers in the system. Merz called this the “biological” aspect of the Fibonacci numbers: writing out any segment of the sequence is like mapping a family tree. The medieval monk’s theories were surprisingly consistent with the themes of works like Giap’s Igloo, Che fare? and Solitary solidary, since they also model the relationship between the one and the many.

![Mario Merz, Fibonacci Napoli (Mensa in fabbrica), or A real sum is a sum of people (S. Giovanni a Teduccio): 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55 uomini hanno mangiato. La proliferazione degli uomini è legata alla proliferazione degli esseri da mangiare e questi alla proliferazione degli oggetti prodotti poiché questi uomini sono operai di una fabbrica di Napoli (Fibonacci Naples [Factory Canteen], or A real sum is a sum of people [S. Giovanni a Teduccio]: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55 men ate. The proliferation of men is linked to the proliferation of the food and the proliferation of the objects produced inasmuch as these men are workers from a factory in Naples), 1971, black-and-white photographs and neon tubing, 67 x 22 ft. 11½ in. x 4 in. (170 x 700 x 10 cm), installation view. Collection Herbert Foundation, Ghent (artwork © Fondazione Merz; photograph by Philippe De Gobert © Herbert Foundation)](http://artjournal.collegeart.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Mangini-10-500x306.jpg)

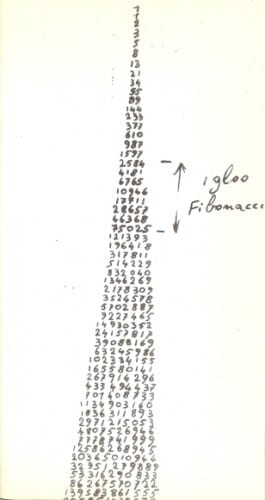

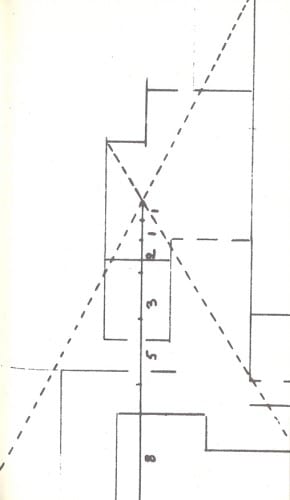

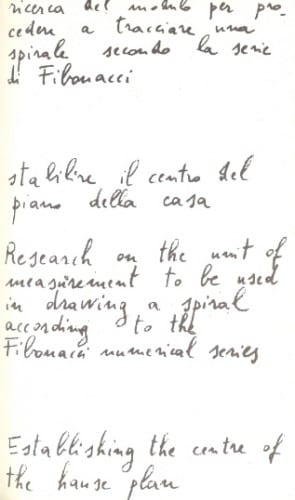

Merz’s first exhibition of works with Fibonacci numbers was in 1970, when, at Bologna’s Civic Museum, he propped against the wall thirteen panes of glass with a series of Fibonacci numbers written on them. Another of the earliest interventions was a project intended for the Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld Germany.55 Although the project was unrealized at the time, he did publish an artist’s book in 1970, Fibonacci 1202/Mario Merz 1970, which reproduces instructional plans and notes for the unrealized exhibition, and offers insight to Merz’s early thinking about the use of the numbers in his art.56 The work was intended as an installation in a residential house-cum-museum designed by Mies van der Rohe during the period when he was director of the Bauhaus. This is significant in that Merz here not only addresses domestic architecture, which he had hinted at it in the igloos, but also intervenes in the specific work of a signal modernist.57 The artist described his intentions for Haus Lange thus: “I didn’t want to put an object inside, I wanted to make an object that would be entirely integrated with the building, yet would be the complete opposite of that building.”58 Merz’s proposed architectural intervention, then, was to exceed the closed, rational space of the Mies building by inscribing it within and inscribing within it an infinitely expansive notation of energy.

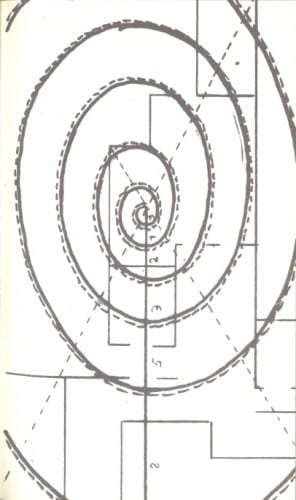

The artist’s book provides a roadmap to the way Merz was thinking about the applications of the Fibonacci numbers to real spaces at Haus Lange and elsewhere.59 In its pages, Merz uses the numerical series to demonstrate the construction of a correct curve for an igloo’s dome, identifying a portion of the sequence that could be translated into material and assembled.60 The bulk of the pages of the book, however, indicate that the main event was to be the construction of a spiral that would challenge, physically and conceptually, the rectilinear constraints of the museum’s building.61 The Haus Lange was designed by Mies as a residence circa 1930 and epitomizes the architect’s rational, geometric style. In Merz’s plans, we can see him establishing the center within Mies’s cubic arrangement of rooms and drawing a spiral that begins from that point in space. In the last of the drawings, a spiral completely overlays the architectural plan of the museum’s galleries, with the first five Fibonacci numbers proscribing the radial distance between each curve. The spiral runs off the page, is cut off on the far left, and briefly reappears at the bottom corners before disappearing from view. This cropping has the significant effect of making the viewer imagine that the form continues infinitely, just out of current view.62 A final inscription following the series of spiral drawings further evidences Merz’s interest in disrupting the logic of the rational building: “La resistenza diminuisce con la dilatazione della spirale.”63 This phrase, “The resistance diminishes with the dilation of the spiral,” refers, on the surface, to the conceptual fracturing of the architectural space: Mies’s rectilinear building yields as the spiral expands. It also could be an argument for using the Fibonacci system to read the shifting momentum of the Italian worker movement following the “Hot Autumn” of 1969, as the traditional labor unions lost their exclusive grip on the ideology of workerism during the rise of Autonomia. More generally, however, it expresses the way in which momentum multiplies the energy initially needed to overcome inertia.

In a 1971 interview with the Italian critic Tommaso Trini, the artist reflected that his early research on the Fibonacci series had led him to specifically consider the “enormous volume of mental, and therefore physical, space at our disposal.” That is, he recognized the contradiction created by bringing the medieval, theological system of ordering the natural world through biological numbers into direct relief with a modern, secular system. The possible viability of both systems, simultaneously, requires an expansion of basic concepts of being in the world. This, Merz argued, “is the ‘political’ value of the application of proliferating numbers to the areas which we make use of.”64 For the artist, this mental space was real territory that could be made available through the expansive thinking catalyzed by his material interventions and conceptual operations.

When pressed by Trini on the relationship between art and politics in his Fibonacci works of the early 1970s, Merz asserted that art need not be overt in its political aims, that instead a radical idea introduced in one sphere, such as “an idea that arises from the study of plant and animal proliferation,” could have a profound effect on something like social politics by undermining an entire system of thought.65 Provisionally, therefore, we might also read Merz’s interest in the energy represented by the spiral and its reconfiguring of rectilinear space as a distinctive way of regarding the political challenges of the moment. As Trini’s questions illustrate, Italy’s social transformations could not be ignored by anyone living in highly industrialized Turin. Merz’s response to the critic betrays that he was aware of these social changes, but, moreover, his work demonstrates that he was thinking structurally, beyond the specifics of strikes and stoppages, in order to see the systems at work. The elaboration of Autonomia’s political theories in the 1970s required exactly this kind of viewpoint in order to elaborate a plan to dismantle those structures and overcome inertia.

![Mario Merz, Fibonacci Napoli (Mensa in fabbrica), or A real sum is a sum of people (S. Giovanni a Teduccio): 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55 uomini hanno mangiato. La proliferazione degli uomini è legata alla proliferazione degli esseri da mangiare e questi alla proliferazione degli oggetti prodotti poiché questi uomini sono operai di una fabbrica di Napoli (Fibonacci Naples [Factory Canteen], or A real sum is a sum of people [S. Giovanni a Teduccio]: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55 men ate. The proliferation of men is linked to the proliferation of the food and the proliferation of the objects produced inasmuch as these men are workers from a factory in Naples), 1971, black-and-white photographs and neon tubing, 67 x 22 ft. 11½ in. x 4 in. (170 x 700 x 10 cm), photograph. Collection Herbert Foundation, Ghent (artwork © Fondazione Merz; photograph by Philippe De Gobert © Herbert Foundation)](http://artjournal.collegeart.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Mangini-11-500x331.jpg)

Drawings from that artist’s book, Fibonacci 1202/Mario Merz 1970, were used to illustrate Paolo Virno’s essay “Dreamers of a Successful Life,” in the 1980 collection of writings on Autonomia. Here Virno, one of the editors of the Roman magazine Metropoli who were unjustly arrested in June 1979 in connection with the murder of Moro, argues that social change will come not from revision of labor laws, but from a fundamental change in attitude of people toward all aspects of activity: “What counts is the qualitative consistency, profoundly varied, of their ‘doing.’”66 Rejecting the system and its hierarchies was not something that could be isolated to work time. Instead, Virno argues that capitalist society conceals the connection between labor and nature in order to alienate the individual from her senses, a situation that must be redressed through the adoption of different criteria of productivity. In the end, he paraphrases Marx’s assertion that the work of art can anticipate these new forms of production without domination.67 Merz’s Fibonacci drawings, footnoting the pages of this argument, illustrate an alternative model of organization and production, precisely in a nature-based system.

While the Fibonacci numbers are the underlying principle on which Merz grounded his artistic investigations into the shifting nature of experience and the radical changes in Italian social structures, the artist made only a few attempts in the early 1970s to connect the Fibonacci research to the direct politics of Italy’s diffuse labor movements. The first of these occasions was in October of 1970, at Francois Lambert gallery in Milan, when Merz installed the first few Fibonacci numbers (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8 . . .) on the wall opposite the gallery’s main door.68 Each of these numbers was attached to neon bars that act as “tails,” visually anchoring the numbers in a broken line. On the opposite wall, above the door, he hung a neon sign reading “Sciopero generale azione politica relativa proclamata relativamente all’arte” (“General strike relative political action proclaimed relatively to art”). This slogan, which refers to the relationship between art and politics, directly counters the series of numbers. Here Merz opposes the topical and the abstract, the single issue and a questioning of the system itself, and the solidarity of a general strike with the solitary act of an artist. He posits these two modes as contradictory, but also connected through their structural opposition.

The connection between the Fibonacci numbers and everyday politics is more visible in Merz’s use of the sequence as a formula for staged encounters between people in works like Fibonacci Napoli: Mensa di Fabbrica (Fibonacci Naples: Factory Canteen, 1971). Made in collaboration with a photographer, it is a series of photographs showing factory workers entering their company cafeteria. In each frame, the number of workers in the assembly corresponds to the Fibonacci ordinals, in order to give tangible form to everyday organizational structures. The first two frames each depict one worker, who is then joined by a second, then a third. In the next picture there are five, then eight, and so forth, until the room is full with fifty-five men. The images act as a sort of filmstrip when displayed on the wall in a horizontal line, as the room quickly progresses from empty to full. Each photograph has a neon number affixed to its frame that identifies and “doubles” the number of workers within it. The neon itself functions as a sign for the energy produced by the communion of individual molecules, as demonstrated in the text works of 1968. The material here reinforces the way the Fibonacci numbers allow Merz to break down the notion of a mass into a perceptibly methodical, natural gathering of individuals. Equally important, since the neon numerals are manifest in the real space of the viewer, they offer a measure of the distance between the viewer and the photographed subjects. They present what the photographs represent.

By using factory workers, Merz deployed the Fibonacci system to give visible order to the kind of assembly seen in the contemporaneous labor movements: the masses occupying the piazza are broken down into an orderly progression of numbers. However, the fact that these workers are shown gathering at lunch—neither at the tasks of their labor, nor at a protest—is significant. Since these workers are not actively performing their role as laborers, but rather are on break, feeding their bodies, the viewer can see them as both abstract laborers and, more sympathetically, as sentient human beings. Merz’s tactic parallels the way Autonomia is meant to permeate all aspects of life, down to the individual needs of a single body, or interactions between one person and another. The artist reprises this work two more times in 1972—using diners in a British pub and in a Turin restaurant—reinforcing the notion that the social impulse is part of the natural state of individual human beings. Merz claimed that these projects displayed the idea that “a series of people in a restaurant is more elementary than a series of numbers (the series is elementary but people assembled for a common function is more elementary).”69 That is, the Fibonacci series is merely a system through which an ordinary social occurrence can be visually described and made comprehensible. Merz’s use of the Fibonacci series and his proposal of this medieval system’s viability in the 1970s enacts a destructuring of a prevailing order by applying an anachronistic concept to a contemporary situation. In the same way that Negri’s concept of self-valorization called for side-stepping the terms of a relationship established in relation to capitalism as it exists, Merz’s work argues for a different system overlaying the current one. The pervasiveness of the Fibonacci numbers in his later work—as the basis for constructing tables, stacking bundles of newspapers, or creating architectural interventions, or as a means to engage with animal forms—indicates the importance that the artist placed on the alternate spaces created by such thinking. What is the artist to do but investigate the machine itself, and lay bare the complexity of his relationship with the world?

![Mario Merz, Fibonacci Napoli (Mensa in fabbrica), or A real sum is a sum of people (S. Giovanni a Teduccio): 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55 uomini hanno mangiato. La proliferazione degli uomini è legata alla proliferazione degli esseri da mangiare e questi alla proliferazione degli oggetti prodotti poiché questi uomini sono operai di una fabbrica di Napoli (Fibonacci Naples [Factory Canteen], or A real sum is a sum of people [S. Giovanni a Teduccio]: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55 men ate. The proliferation of men is linked to the proliferation of the food and the proliferation of the objects produced inasmuch as these men are workers from a factory in Naples), 1971, black-and-white photographs and neon tubing, 67 x 22 ft. 11½ in. x 4 in. (170 x 700 x 10 cm), photograph. Collection Herbert Foundation, Ghent (artwork © Fondazione Merz; photograph by Philippe De Gobert © Herbert Foundation)](http://artjournal.collegeart.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Mangini-12-500x331.jpg)

•••

Merz’s exploration of the one and the many, when read across the many forms of its investment in his art, implores us to consider that the artist does indeed operate in the nomadic realm of the body without organs, but without the nostalgic notion of bohemian individualism too often attached to the image of the artist-nomad. The collective individualism espoused by Autonomia’s theorists as necessary for a new politicization of the worker was part of a historical discourse that included the image of the nomad. The use of this term to delineate Merz’s artistic identity, however, has remained superficial. It neatly packages the artist and the political significance of his project in a digestible, consumable metaphor. It is only in looking beyond the Romantic categories of individual artistic agency that Merz’s project emerges as a theoretical and material exploration of systems and structures. The full import of his work comes into view when the many aspects of this project are regarded together.

That is, if we read the seemingly disparate components that appear to dominate Merz’s art—neon, igloos, spirals, Fibonacci numbers—transversally, they are revealed to intersect with the imbrications of the individual and the collective at different points. Moreover, through his specific use of materials like beeswax and neon, Merz’s artworks are pregnant with implications that underlie what appears on the surface. By injecting forms and referents with ambiguity, as well as building in layers of potential signification, he indicates the complex interdependence of individual experiences and shared meaning. This mode of critical investigation is parallel to the approach of the most influential political theories of the 1960s and 1970s in that it articulates its core theory through multiple, diverse avenues. Merz’s tactical disruptions of prevailing systems, especially via the Fibonacci numbers, underscore the force of the physical objects he makes. The tension between the individual and the collective, which he first explored in his topical text works of 1968–70, becomes an abstract machine for exploring the same issues via the Fibonacci numerical system.

Seen this way, Merz’s work argues for maintaining the paradox of the artist and the individual subject, in relation to the social world: limited by a necessary, instinctual fidelity to the self, but limitless in an anonymous solidarity with others. His entreaty to prize the irresolution of the one and the many, to celebrate the singular and the infinite, and to see the microcosm of the neon tube as the macrocosm of universal energy must be taken together. It is only then that they are revealed to create a theory of radical subjectivity as at once separate from and together with the world he explores through his art. Like the illegible message produced by Camus’s artist, Merz’s maintenance of this fundamental impasse catalyzes a conceptual transformation in the viewer: it creates a space in which in such opposites as “solitary” and “solidary” easily coexist in the same expression. In the Fibonacci numbers that would permeate his work for the next three decades, Merz recognized a system for enacting a collective revolution with decidedly artistic means, changing one individual consciousness at a time.

The author wishes to thank Luisa Borio, the Fondazione Merz, Paolo Mussat Sartor, the Herbert Foundation, the Kunstmuseen Krefeld, Barbara Gladstone Gallery, and the CCA VS Writers Group, as well as Gwen Allen, Geoff Kaplan, Jordan Kantor, Tirza True Latimer, and Denis Viva for their generous support and feedback.

Elizabeth Mangini, associate professor and chair of visual studies at California College of the Arts, has published numerous articles on postwar Italian art, and she serves on the editorial board of Palinsesti. Currently, she is writing a monographic book on the sculptor Giuseppe Penone, the working title of which is “Seeing through Closed Eyelids.”

- Merz’s first solo exhibition of these objects was at Galleria Sperone in Turin in January 1968. For a period review of that show, see Daniela Palazzoli, “Mario Merz” recensioni/reviews, Bit 2, no. 1 (March–April 1968): 26–29. In 1968 Merz exhibited his objects in seven major European exhibitions, making it a particularly fecund year for the experienced artist. ↩

- The theoretical first number of the Fibonacci sequence is zero, but most mathematicians begin with one for the sake of convenience. The mathematician Fibonacci (ca. 1170–ca. 1250, Pisa) was also known by the name Leonardo Pisano or di Pisa. The name Fibonacci is a contraction of “figlio di” or “figlius” Bonacci, his father’s surname. See R. E. Grimm, “The Autobiography of Leonardo Pisano,” Fibonacci Quarterly 11, no. 1 (February 1973): 99–104. The numerical sequence was known in the Arabic world for nearly a millennium before Fibonacci, but he is credited with bringing it to the Latin world and connecting it with a specifically Catholic theological worldview. Fibonacci had observed that an endless numerical sequence (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, etc.), with each number arrived at by summing the two preceding numbers, appeared to correspond to the number of petals on a flower, the number of seeds in a fruit, and the number of offspring produced by a pair of rabbits. In the centuries that followed Fibonacci’s publication of his theory in Liber Abaci, the numbers were employed to explain everything from the structure of the human body and the progeny of animals, to the Renaissance idealization of the Golden Mean and Le Corbusier’s twentieth-century Modulor architectural system. ↩

- Merz’s Fibonacci works officially date from January 1970, when he exhibited an untitled audio-video piece, as well as thirteen glass panels illuminated from behind with neon bars, with Fibonacci numbers written on each in white medium. The untitled sound work and the glass and neon Serie di Fibonacci were shown in the exhibition Gennaio ’70 at the Museo Civico di Bologna. ↩

- These three characterizations are from different eras, in articles reprinted in the most recent major catalogue of Merz’s work, Pier Giovanni Castagnoli, Ida Gianelli, and Beatrice Merz, eds., Mario Merz (Turin: Fondazione Merz, 2005), published in both Italian and English: Wieland Schmeid, “Mario Merz Review” (1974), 61; Daniel Soutif, “The Panic Drawing of Mario Merz” (2001), 134; and Marlis Grüterich, “The Transcendental Realism of Things and the Aesthetic Science of Life instead of Historical Humanism” (1983), 87. ↩

- Grüterich, 84. In a 1990 essay, the curator Rudi Fuchs asks if the art of Mario Merz is “a denial of the Fall of Man, of original sin, and this an attempt at the allegorical recreation of Paradise?” Fuchs, “Allegories,” in Mario Merz: Terra Elevata o la storia del disegno (Rivoli: Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Castello di Rivoli, 1990), rep. in English in Mario Merz (2005), 110. ↩

- Jacopo Galimberti argues that Arte Povera emerged not only alongside the political context, but also in dialogue with it. For a detailed analysis of the theoretical and political implications of Celant’s construction of Arte Povera, see Galimberti, “A Third-Worldist Art: Germano Celant’s Invention of Arte Povera,” Art History 36, no. 2 (April 2013): 418–41. In the case of Merz, curators like Danilo Eccher, a generation younger than Celant, have argued that the natural aspect of Merz’s work is too obvious and that the significance of his work can only come from a synthetic view to his body of work and its “theoretical horizon.” See Eccher, Mario Merz (Turin: Hopefulmonster, 1995). The art historian Emily Braun ties Merz’s work to Claude Lévi-Strauss’s contemporaneous writings about corporeal interaction with the environment. See Braun, “Mario Merz: Ethnographer of the Everyday,” in Mario Merz: The Magnolia Table, ed. Gian Enzo Sperone, exh. cat. (New York: Sperone Westwater, 2007), unpaginated (8). Braun argues that Merz’s use of Fibonacci numerals is comparable to Lévi-Strauss’s notion that the propensity for order was the “concrete science” of primitive humans. Braun’s argument, connecting the structuralist analyses of such texts as the “The Raw and the Cooked” (1964) to issues of bodily interaction with the environment, is complementary to my own interests, but maintains echoes of Celant’s romantic language that I seek to examine more closely. In the specific case of the Fibonacci Santa Giulia installation, she notes that the numbers add “perceptual acuity into the seemingly most inconsequential workaday routine.” ↩

- Sylvère Lotringer and Christian Marazzi, “The Return of Politics,” in “Autonomia: Post-Political Politics,” ed. Lotringer and Marazzi, special issue, Semiotext(e) 3, no. 3 (1980): 8–10. ↩

- The first official meeting of Autonomia is recorded as taking place in September 1973, but the theoretical underpinnings of the movement began as early as the 1950s. See “Workerist Publications and Bios,” Semiotext(e) 3, no. 3 (1980): 179. ↩

- See Germano Celant, “Mario Merz: The Artist as Nomad,” Artforum 18, no. 4 (December 1979): 52. Celant also subtitled the lead essay of the exhibition catalogue for Merz’s 1989 Guggenheim retrospective “Nomadic Cartography,” and he used the term “nomad” in Merz’s obituary: Celant, “Passages: Mario Merz,” Artforum 42, no. 5 (January 2004): 25–26. ↩

- Germano Celant, “Arte Povera: Appunti per una guerriglia,” Flash Art 5 (November–December 1967): 3. ↩

- Germano Celant, Art Povera (New York: Praeger, 1969), 227 and 299. ↩

- Germano Celant, “Arte povera,” trans. Paul Blanchard, in Arte Povera = Art Povera (Milan: Electa, 1985), 123. The essay first appears in Celant, Arte Povera (Milan: Gebriele Mazzota, 1969), but the English version published simultaneously by Praeger (see previous note) has a truncated form of the essay that excludes the statement that Arte Povera does not represent so much as present. The statement is added back in the 1985 Arte Povera = Art Povera, which anthologizes the early writings on Arte Povera. ↩

- Celant, “Arte povera” (1969), 225. ↩

- Celant writes that for these artists, “existence means drifting from one context to another, adapting to local foods and customs; their lifestyle never crystallizes into anything definitive or stable.” Germano Celant, “Mario Merz: The Artist as Nomad,” 52. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari not only participated in Italian intellectual circles of the 1970s and collaborated with revolutionary cultural outlets like Radio Alice in Bologna, but also actively wrote in defense of intellectuals like Antonio Negri who were arrested after being (wrongly) accused of secretly leading the Red Brigades (Brigate Rosse) terrorist group. See, for example, Deleuze’s letter published in La Repubblica in May 1979, rep. as “Open Letter to Negri’s Judges,” in Semiotext(e) 3, no. 3 (1980): 182. For notes on Guattari’s involvement, see ibid., 108. ↩

- Celant, “Artist as Nomad,” 52. Gilles Deleuze published a major essay about “nomad thought” in 1970; see Robert J. Tally Jr., “Nomadography: The Early Deleuze and the History of Philosophy,” Journal of Philosophy 5, no. 11 (Winter 2010): 17. In Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (1980; Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1987) and other writings, the authors do not provide a strict definition of the nomad, but introduce the concept in many different ways, of which the relationship to the state is only one. See also the excerpt of the book published in English as Deleuze and Guattari, Nomadology: The War Machine, trans. Brian Massumi (New York: Semiotext(e), 1986). See also “Nomad” at www.rhizomes.net/issue5/poke/glossary.html, as of June 28, 2016. ↩

- See Deleuze and Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus, 570–71, n66 and n67. ↩

- Indeed, one of the often-rehearsed stories of Merz’s biography notes that he had spent time in jail for handing out anti-Fascist leaflets during World War II, when the youngest members of the Arte Povera group weren’t yet born. In a 1983 interview, Merz recalls his wartime (1943) involvement with the anti-Fascist movement Giustizia e Libertà. In this interview he notes that looking back at the old writings of this group reminds him of the writings of Autonomia “today.” This example makes it clear that Merz was following and had read the political theories of Autonomia. See Germano Celant, “Interview with Mario Merz, Turin, 1983” in Mario Merz, ed. Celant, trans. Joachim Neugroschel (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, and Milan: Electa, 1989), 45. ↩

- Harald Szeemann, “Mario Merz,” in Mario Merz (Ascona: Museo Comunale d’Arte Moderna, 1990), rep. in English in Mario Merz (2005, no trans. listed), 98–106; and Eccher. ↩

- The term anni di piombo was retroactively applied to the decade. It originated as the Italian title of Margarethe von Trotta’s 1981 cinematic dramatization of German left-wing terrorism, Die bleierne Zeit. In the United States the film was released as Marianne and Juliane. The term connotes the bombings and gun violence that characterized the decade’s “strategy of tension,” when far-left and far-right groups provoked each other into ever more violent responses. See Richard Drake, “Italy in the 1960s: A Legacy of Terrorism and Liberation,” in South Central Review 16, no. 4, and 17, no. 1 (Winter 1999 and Spring 2000): 62–72. ↩

- In 1980, Sylvère Lotringer and Christian Marazzi note that more than fifteen hundred “intellectuals and militants of the class movement” were in jail in Italy. See Lotringer and Marazzi, 9. ↩

- See Antonio Negri and Verina Gfader, “The Real Radical,” in The Italian Avant-Garde: 1968–1976, pub. as vol. 1, EP series, ed. Alex Coles and Catharine Rossi (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), 206. ↩

- The radical offshoot of the student-worker movement was founded in Turin in 1969, and published an influential eponymous newspaper throughout the 1970s. Gian Enzo Sperone told me that he used to find warnings and slogans outside his gallery door in those years, owing to his work with American artists like Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Roy Lichtenstein. Sperone, e-mail to the author, October 13, 2009. ↩

- When asked about possible historical connections between groups like Archizoom or Arte Povera and his own experience as a writer and labor organizer, Antonio Negri remarked that there was little dialogue between that art and his experience of the politics. He remarked, “The only thing interesting about the avant-garde for me was the opportunity it offered to make some money—we were asking for paintings from artists in order to sell them to fund our activities.” He recalled receiving paintings from Mario Schifano, Roberto Matta, and René Burri. Negri and Gfader, 206. ↩

- Giap’s book was originally published in French in 1961, and the radical publisher Feltrinelli issued the first Italian version, complete with foreword from the Cuban edition by Ernesto “Che” Guevara, in 1968. The book contained four essays on revolutionary strategy, illustrative maps, and a timeline of the current battles between American troops and the Vietcong. It was advertised on the cover as containing “The psychological, political, and military techniques of the fight against imperialism for its inevitable defeat.” Vo Nguyen Giap, Guerra del popolo, esercito del popolo, trans. Mario Antomelli (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1968). ↩

- Writing about Merz’s use of language, in general, the Italian curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev has noted that the circumvention of the igloo necessary to read the phrase causes the viewer to experience a shift in ground and thereby to experience Giap’s paradox. See Christov-Bakargiev, “‘Thou wilt give thanks when the night is spent’: On Words in the Art of Mario Merz,” in Mario Merz (2005), 149. ↩

- Merz in Germano Celant, “Interview with Germano Celant, Genoa, 1971,” in Mario Merz (1989), 106. ↩

- In a typical example of the romantic igloo/nomad dyad in the literature on Merz, the curator Harald Szeemann has written that the igloo is “the first artifact after the Expulsion from the Garden of Eden” and, above all, “the basis for belief in the ancient, magnificent legends . . .” Szeemann, 104. ↩

- Installation views of this show at the DDP reveal that this first igloo was made with an opening or door that could potentially allow viewers to enter the structure. According to Merz archivist Lusia Borio, this was only to allow the artist to finish the work from the inside, and the igloos were not meant to be entered. Conversation with author, July 28, 2016. For the fascinating history of the DDP, see Robert Lumley, “Arte Povera in Turin: The Intriguing Case of the Deposito D’Arte Presente,” in Marcello Levi: Portrait of a Collector, ed. Francesco Manacorda and Lumley (Turin: Hopefulmonster, 2005), 89–107. ↩

- Students had been occupying Turin’s Palazzo Campana since the fall of 1967. The Palazzo Campana was the seat of the mathematics department of the University of Turin. The title of Merz’s work Solitario solidale often appears translated as “Solitary solidarity,” instead of “Solitary solidary.” I here insist on the latter, more literal translation because in the original French, as in Merz’s Italian, the two words are adjectives, and the equivalents of “solidarity” are different words. English translations of the story by Albert Camus, in which this phrase originates, also translate the French as “solidary.” See note 34. ↩

- See Christov-Bakargiev, 148–65. ↩

- The persistence of the igloo form throughout Merz’s career has lent further credence to the romantic language of the wandering artist. The critic Wieland Schmied called him the “igloo-man” after seeing his installation at Documenta V in 1972, and, more recently, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev has argued that the igloos are displaced self-portraits, forms that are both present and absent, just “like a nomad.” See Schmied, “Mario Merz Review,” in Mario Merz (Berlin: DAAD, 1974); rep. Mario Merz (2005), 58; and Christov-Bakargiev, 149. ↩

- Harald Szeeman mentions this work in passing in his 1990 essay. He argues for reading the phrase and the igloos as utopian aspirations: “This perfect thing led to positive utopias and evoked myths: [Merz ↩

- Note that the first version of Solitary solidary, like the first version of Sit-In, consisted of beeswax covering a piece of wire mesh, which was set into a metal armature. The cooking vessel appeared in later versions of both. ↩

- Albert Camus, “The Artist at Work” (“Jonas, ou l’artiste au travail,” 1957), in Exile and the Kingdom, trans. Justin O’Brien (trans. 1958; New York: Vintage, 2007). I discovered this connection through a painting by Jordan Kantor, to whom I am grateful for this reference to another aspect of Merz’s work. ↩

- Merz in Celant, “Interview with Germano Celant, Genoa, 1971,” 106. ↩

- Herbert Marcuse, The Aesthetic Dimension: Toward a Critique of Marxist Aesthetics (1977), trans. Marcuse and Erica Scherover (Boston: Beacon Press, 1978), 17. ↩

- The German artist Joseph Beuys also used beeswax in his early sculptures, and much has been made of an artistic link between Beuys and Merz, including a show and catalogue edited by Germano Celant in Naples titled Joseph Beuys: Tracce in Italia, exh. cat. (Naples: Amelio Editore: 1978). However, since much of this vein of argumentation centers on the shamanic, nomadic reading of Merz that I am trying to counter, I do not pursue this here. Instead, I agree with Emily Braun’s assessment that the common attempt to put these two figures together and to read their material interests in tandem “misconstrues [Merz ↩

- The import of beeswax has been deepened though discussion with students in a seminar in spring 2015. Geoff Kaplan has provided me with an initial reading list on honeybee social structures and has patiently answered many of my questions about his backyard hives. For more on honeybee sociality, see “The Colony and Its Organization,” the website of the Mid-Atlantic Apiculture Research and Extension Consortium, at https://agdev.anr.udel.edu/maarec/honey-bee-biology/the-colony-and-its-organization/, as of June 28, 2016. ↩

- Thomas D. Seeley, introduction to Honeybee Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 5 (Kindle locations 104–6). ↩

- Lotringer and Marazzi, 9. The 1980 issue of Semiotext(e) edited by Lotringer and Marazzi was an early attempt to collect foundational and contemporary texts on Autonomia. ↩

- All fluorescent, closed-cathode tube lights are commonly referred to as “neon lamps,” but true neon produces red light. Colors like white, blue, yellow, and green are produced by other noble gases, such as helium, xenon, and argon, along with phosphates and mercury. For ease of legibility here I conform to the common usage when describing Merz’s works. For more on neon’s history, see Christoph Ribbat, Flickering Light: A History of Neon, trans. Anthony Matthews (London: Reaktion, 2013), 7–8, originally published as Flackernde Moderne: Die Geschichte des Neonlichts (Stuttgart: Steiner Verlag, 2011). ↩

- Antonio Negri, “Domination and Sabotage” (1977), trans. Red Notes, in Autonomia: Post-Political Politics, 63. ↩

- One notable outlier is the curator Dieter Schwartz, who argues that Merz’s Che fare? has “nothing to do with political theory,” instead modeling the romantic attitude of an artist for whom the world is always full of renewed possibility. Schwartz, “‘The work is here’: Mario Merz between Presence and Representation,” in Mario Merz (2005), 9. A 2010 exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein used this phrase for a historical show of Arte Povera, alluding to the fact that the core period of the movement occurred within a period of social and political turmoil, but simultaneously arguing that the works have no “discernable political motivation.” See Che fare? Arte Povera—The Historic Years, ed. Friedmann Malsch, Christiane Meyer-Stoll, and Valentina Pero, exh. cat. (Heidelberg: Kehrer, 2010), 14. For a typical account that links to Lenin, see Christov-Bakargiev, 150. Also note that the phrase “What is to be done?” is still in use today to refer to the connection between art and leftist politics. It has recently been used as one of three main themes for the 2007 Documenta 12 exhibition in Kassel, Germany. Chto Delat? is also the name of a Russian artist collective, active since the early 2000s. ↩

- As mentioned above, Merz made a second version of this work in June 1969. For his solo show at the commercial gallery L’attico in Rome, he used a green rubber solution to write the phrase in large letters on the wall of the basement gallery, above a water tap that was turned on and left running during the exhibition. I am not discussing the later work here, in order to stay on track with the neon works; for an account of it, see Marcella Beccaria, “Chronology,” in Mario Merz (2005), 213. The artist also later published photo-collages of this installation, retracing the letters on the photograph with pink clay. See the example in the collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. ↩

- Nikolay Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky, What Is to Be Done? Tales about New People, trans. Benjamin R. Tucker, expanded by Cathy Porter (London: Virago, 1982). ↩

- The Italian studies scholar Judy Rawson cites Chernyshevsky as the first literary use of the phrase. Even further back, she argues, the phrase “Quid ergo faciemus?” (What then must we do?) appears in the Bible’s New Testament (Luke 3:10–11), as a question directed to John the Baptist. Leo Tolstoy directly appropriated this construction in 1886, though in 1905 he used the formulation Chto Delat?. Rawson, “‘Che fare?’: Silone and the Russian ‘Chto Delat’ Tradition,” Modern Language Review 76, no. 3 (July 1981): 556–65. ↩

- Ignazio Silone, Fontamara (1933/1960), trans. Eric Mosbacher (New York: Signet, 1981). ↩

- See Mario Merz (2005), 210. ↩

- While outside the immediate scope of this argument about Che fare?, I note here that Merz’s newspaper works are tied to the Fibonacci sequence. See, for example, his 1972 installations at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (January–March 1972), or the work 6756 (1976), which comprises eighty-three stacks of newspapers, glass panes, and neon Fibonacci numbers. ↩

- Rawson, 565. ↩

- Che fare also published texts by international writers and focused on subjects such as workers’ newspapers. In the introduction to the first issue, the collective authors argue that art and literature have now become products made for the market, more than for independent reasons. They also caution that in attempting to understand and perhaps combat this situation, real autonomy must be separated from utopian autonomy. Che fare: Bolletino di critica e azione d’avanguardia 1 (May 29, 1967): 5, 69–71. ↩

- Franco Berardi, “A Voce—IV: Il Partito, l’organizzazione, e la classe,” Che fare 4 (Winter 1968–69): 82–88. Berardi, was not only one of the main student leaders of the 1970s movements, arrested for subversive actions, but also a writer who contributed to Lotringer and Marazzi’s 1980 book on Autonomia. See Bifo, “Anatomy of Autonomy,” trans. Jared Becker, Richard Reid, and Andrew Rosenbaum, in Autonomia, 148–170. ↩

- Berardi, “A Voce,” 88. ↩

- See Bifo, “Anatomy of Autonomy,” 148–170. ↩

- The Haus Lange project would have been one of the first public uses, had it been realized. Merz first used the Fibonacci numbers in 1968 as neon lamps hung on the walls of his kitchen. In 1970 he exhibited a number of works using glass panes and neon lamps to further explore the numerical sequence. The untitled work mentioned here appeared in the exhibition Gennaio ’70 at the Museo Civico di Bologna, along with an audio-video piece in which the numbers were made manifest in music. ↩

- Mario Merz, Fibonacci 1202/Mario Merz 1970 (Turin: Sperone Editore, 1970), unpaginated. In this artist’s book, most texts appear in Italian with facing English translation; a few appear only in Italian. Where practical I have quoted the original English, and I have noted where translations are my own. ↩

- See Merz in Tommaso Trini, “Intervista,” Data, September 1971, 21. ↩

- Merz in Celant, “Interview with Germano Celant, Genoa, 1971,” 109. ↩

- Some of the other spaces Merz “interrupted” with Fibonacci numbers during the 1970s include the spiral of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York, a prison in Pescara, Italy, and a gallery at Documenta V in Kassel, Germany. ↩

- Fibonacci Unit (1970) is a spindly igloo with segmented legs that correspond to the expansion of the Fibonacci numbers, and it hints at one object he might have exhibited in Krefeld. Note that an aesthetic precedent for Merz’s interest in the Fibonacci numbers as a building rubric may be found in the Swiss-born architect Le Corbusier’s concept of the “Modulor,” an anthropometric scale of proportions first published in 1948 and expounded in an address at the 1951 Milan Triennale. Used in a number of Le Corbusier’s designs, the Modulor aimed to bridge seemingly incompatible systems of measurement by using a human scale. See Romy Golan, Muralnomad: The Paradox of Wall Painting, Europe 1927–1957 (New Haven: Yale University Press: 2009), 241. ↩

- A section of the book is titled: “Research on the unit of measurement to be used in drawing a spiral according to the Fibonacci numerical series.” Merz, Fibonacci 1202/Mario Merz 1970, unpaginated. ↩

- When Merz later created the beeswax sculpture Spirale Haus Lange, (1970) 1981, one can see a glimpse of the material form the work might have taken, but as a discrete object it remains a visibly intact spiral, without the critical friction that would have come from it visually piercing the walls of Mies’s modernist house. ↩

- Merz, Fibonacci 1202/Mario Merz 1970, unpaginated. ↩

- Merz in Trini, 21. ↩

- Ibid. Fibonacci is also credited with introducing Arabic numerals to Europe, a system that eventually surpassed the Roman numeral system. For more on Fibonacci, see Richard Dunlap, The Golden Ratio and Fibonacci Numbers (Singapore and River Edge, NJ: World Scientific, 1997), and in Italian, see Fibonacci tra arte e scienze, ed. Luigi A. Radicati (Pisa: Cassa di Risparmio, 2002). ↩

- Paolo Virno, “Dreamers of a Successful Life,” trans. Jared Becker, in Autonomia, 112. ↩

- See ibid., 116. ↩

- Merz’s longtime assistant, Mariano Boggia, gave an account of the installation of this work in a lecture at the Henry Moore Institute: Boggia, “Via Borgonuovo 2, Milano, giovedi 1 ottobre 1970, alle ore 19” (London, Henry Moore Institute, October 19, 2011), at www.henry-moore.org/hmi/online-papers/papers/mariano-boggia, as of June 28, 2016. ↩

- Mario Merz, I Want to Write a Book Right Now, ed. Marisa Merz, trans. Paul Blanchard (Turin: Hopefulmonster, 1989), 97. The Turin work is titled A real sum is a sum of people, 1972. A similar project in a London pub is featured in the artist’s book Fibonacci 1202/Mario Merz 1972. ↩