Filmmaker Ericka Beckman often uses games as structuring devices in her films and videos that combine minimalist and punk aesthetics. In this conversation, Beckman discusses her 1983 film, You The Better, situating it within a form of expanded performance and interdisciplinary practice. This interview was conducted over a series of email exchanges in August 2016.

—Mary L. Coyne

Mary L. Coyne: You’re known as a filmmaker, but your work consistently includes performance. How do you combine performance and film and how is your current approach different from the one you took in the 1980s?

Ericka Beckman: In the 80s I sought to bring together performance and other types of movement in the frame, to understand causality, correspondence, and simultaneity. At that period I was deeply investigating how you read moving images that are created through double exposures on the same frame, whether that is two performers or a performer and an animated set or prop. I called it the “dependent frame.” I didn’t see myself doing performance art per se, but I was committed to using film as a performance medium, both for the staging of the action in the frame as well as the interaction of live action with animation in the frame. I am still engaged with all features of 16mm production, including the building of the sets, props, costumes, and the shooting.

I am an artist who made films alongside the punk filmmakers in New York in the 80s, and after the structural filmmakers of the 70s. I hope a new audience for my work will see the continuum between my work and historic filmmakers who preceded me—like Andy Warhol, Hollis Frampton, Paul Sharits, Owen Land, and Amos Poe—but also the break I made from structural filmmakers of the 70s by incorporating the body and performance. My work shows a strong connection to my peers in music, such as Rhys Chatham and Glenn Branca, and the minimalists who inspired them, like Terry Riley and Steve Reich.

Coyne: Could you expand on your relationship to structural film techniques including the formal emphasis on time and close readings of objects compared with the almost violent level of activity in your films?

Beckman: I was a part of the 80s downtown music scene in that everyone either played in a band, hung out with a band, or followed a band. The music scene was completely integrated in the downtown performance and art scene. There were events at commercial galleries between shows of composers like Robert Ashley, “Blue” Gene Tyranny, Jill Kroesen, Laurie Anderson, Steve Reich, and others. I was mostly interested in composers who were trained in composition. I attended the California Institute of the Arts (Cal Arts) before coming to New York in order to be around the music department. It was essential for my film work to have a musical component. I went to Cal Arts to be close to John Bergamo and his percussion ensemble. That was a life-changing experience, because Cal Arts also had a famous gamelan orchestra and African percussion classes.

Upon moving to New York, I was interested in continuing this closeness by attending and following the work of Branca and Chatham in particular. When I was in the Whitney Independent Study Program, I had Philip Glass as a presenter for a full day. Glass brought to life the many theories of structuralism that I had been studying as an artist. Formalism, phenomenology, and structuralism were at the heart of how I understood the art-making process, and he showed how they related to music.

Since my work dealt with causal sequences, as film temporally links shots to other shots and creates meaning through repetition and building systems, I found musical structure—especially that structure explored by the contemporary musicians I mentioned above—completely compatible with my work. I learned from what they were doing. I felt the same kind of patterning and creation of form through repetition in 70s dance.

Coyne: Is this more of the coming to fruition of the postmodern dancers like Trisha Brown and Douglas Dunn?

Beckman: Yes, Trisha Brown, Simone Forti, Pooh Kaye, and Lucinda Childs, especially. It’s important to underscore the notion of relativity in the arts that was vital and creative during that time. Understanding what an “object” or an “image” means is only relative to its context. There is no intrinsic truth outside the context. Therefore, all qualities and attributes of an image must refer to at least two sets of interactions in time.

Music explores its context. Forms are created from repetition. Overtones are a great example of this. The sound emerges from the acoustics of the space, and the spacing and rhythms of the notes and their tone. Musical composition seems to favor repetition. If a composition is built on repetition, a change in any unit within that repetition is a cause for any change at a later time in any variable in the composition.

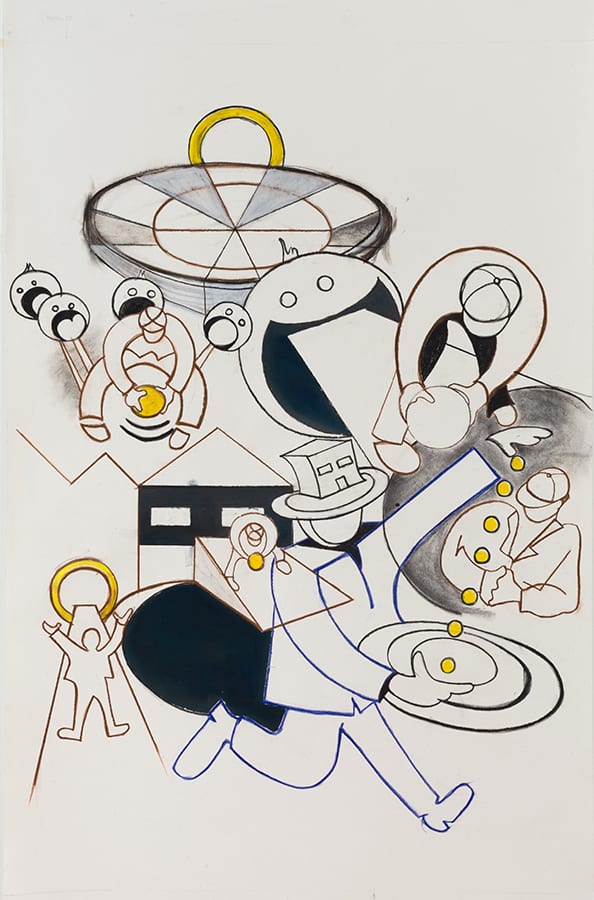

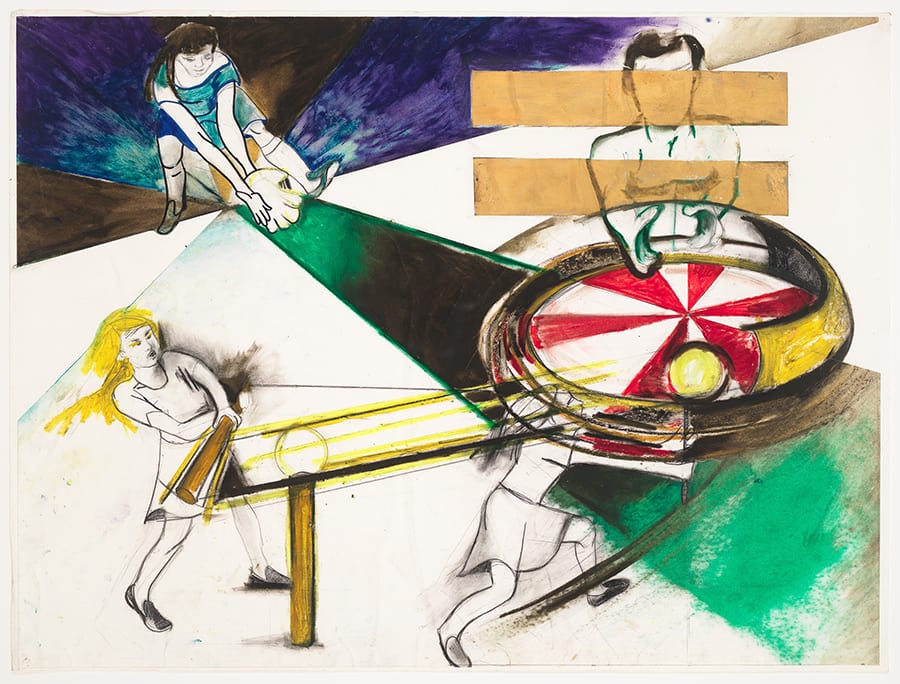

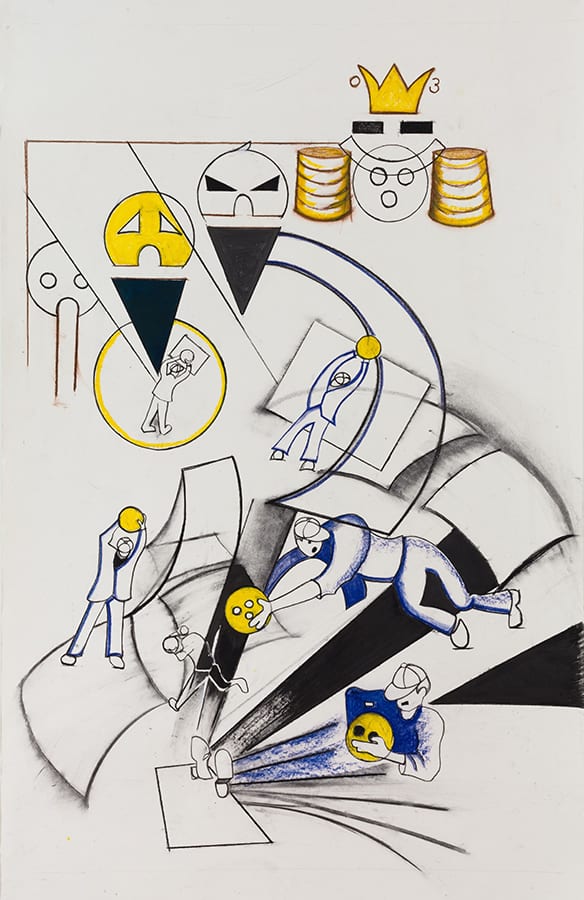

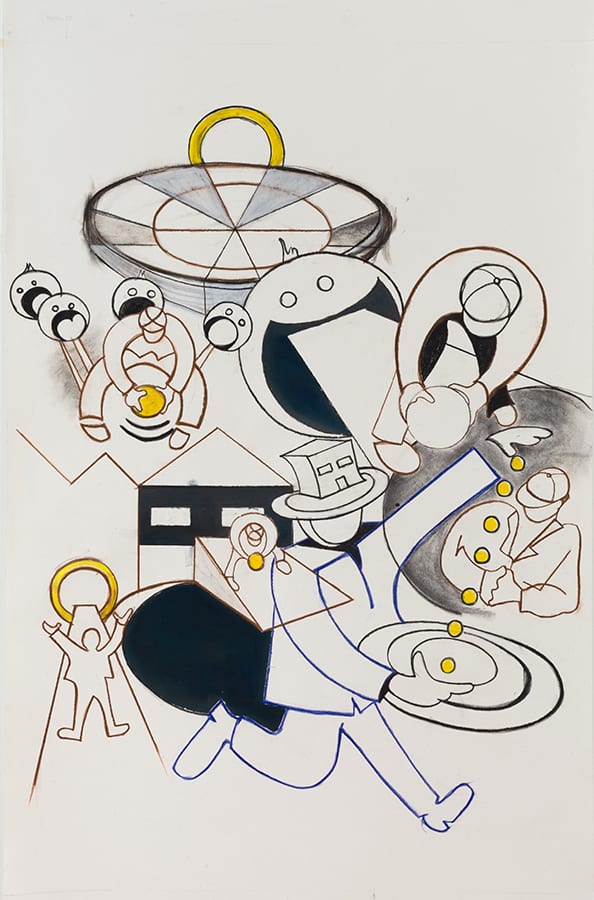

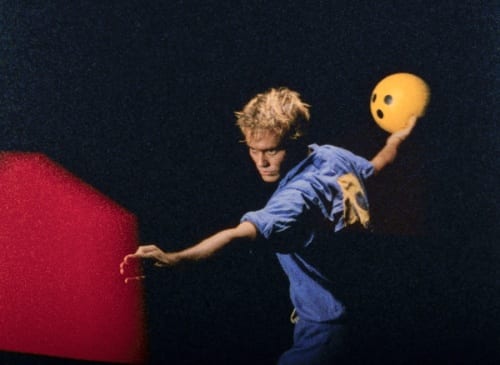

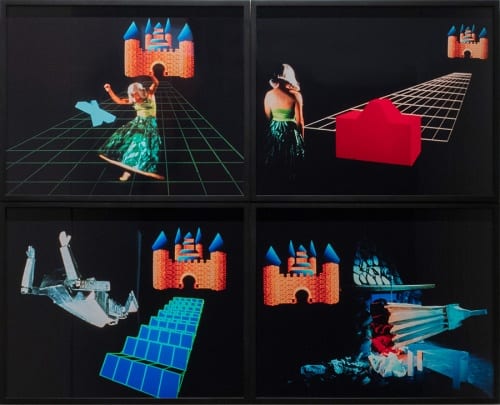

Coyne: I’m interested your film You The Better (1983). It was originally produced as a 16mm film in which a team of uniformed players performs the mechanics of a game with the goal of beating the off-camera, mechanized “house.” The rules of the game aren’t always clear, and the players come in and out of the action passing around a yellow ball—a hybrid between a bowling and volley ball—when on the offense, or taking defensive postures to block or thwart advancement. As the performance continues, one gets the sense that there is no actual solution—no chance of winning. For the film, you created the costumes and a complete video-game-like environment including flashing slogans such as “Take a Shot at the Wheel” and “Your Selection Please” as well outlines and backdrops of a recurring house pattern that alternated in blues and reds through which the players could move. These props were included in the work’s installation at Mary Boone Gallery in New York (Ericka Beckman: You The Better, March 7–April 25, 2015) and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (Less Than One, April 7–December 31, 2016). Can you talk about the sets and how they’re part of the work? How does presenting the work as an installation implicate the viewers in the work or the game?

Beckman: I am currently trying to present my films more to audiences in galleries or museums. To aid me in this, I am building sets to display the films. It is natural for me to do to this since this is how I wanted the films to be seen years ago. It wasn’t possible to do this before we had digital resources and then a new audience had to find me. So it’s been a wonderful set of three years now—I have been able to look through drawings and notes in my notebooks from the period in which I made the work, and find ideas for the props and installations that I can use today.

In the case of You The Better, the idea was to build a sculptural element that would literally be the reference to the film’s animation of house motifs and that would animate with the film. This house motif is a lively symbol that changes its meaning or association as the film progresses from the beginning to the very end. In my new work, I am working with multiple screens and integrated lighting, as in the installations at the Walker and Mary Boone. I am giving the projector a role in the experience of watching the screens. I am looking at all the elements in the room as performing an action of some sort.

Coyne: What are your thoughts on the idea of liveness in sport, in games, in performance? As in the importance—or requirement even—of witnessing an action in person or in a theater, performance space, stadium, or field. It’s a concept that since Derrida’s questioning of liveness and presence we could easily call absurd, but there’s a value that continues to be placed on it.

Beckman: My images are constructed by action, in the truest sense, in every way. I produce them with a motion picture camera. Everything is based on a movement, and a relationship between movements in motion in the picture frame. My entire production philosophy is based on action, whether it is my action (as in Tension Building, 2014) or in the mind of the audience induced by a performer on the screen. Since the alignment of live action and animation is superimposed on the film frame in production and not in the postproduction of the film, I leave a lot to chance. I willingly leave myself open to the chance juxtapositions of these elements, and therefore incorporate more play in my direction on set. Since I use game play as a structuring device, I am involved in competition, integrating or challenging a rule-based system, action and gesture as a language, integrating the body within a physical space and obstacles, and engaging with the intuitive mind to solve problems.

Coyne: You’re interested in the chance element of games, but games rely on structure and there are typically only a set number of possible outcomes. Can you talk about this dichotomy?

Beckman: I found these notes in my notebooks from when I created You The Better:

What is Chance?

Chance is an irreversible operation, or we think of it as uncertainty.

Once chance is understood as an irreversible operation, then the notion of probability is constructed as a deduction.

Ashley Bickerton, the performer in You The Better, says in the film: “You can’t do the same thing twice unless it happens by chance.” When taken in small amounts of trials, the notion of chance is more obvious than larger amounts of trials: a prediction of frequency becomes apparent. At first in You The Better, the players think that the house is the chance element. Their game is to conquer chance and the house through their own effort.

Coyne: Could you talk more about that idea of beating the house? It’s a simple but incredibly complex psychological societal behavior: participating in a seemingly futile action even as we constantly remind ourselves that we ultimately don’t have agency. Even the political conversations of late echo this.

Beckman: The 1983–84 while I was production with You The Better was a time of change from a failed utopian optimism to a false political front. The ideals of the 70s had caved in. The student demonstrations asked for representation in the political system—a seat at the table of power while keeping the system intact. It was more like a changing of the seats, or musical chairs, than real change. Reagan had come into power with a strong capitalistic agenda, carrying with it a series of diversion tactics to hide the truth of what his economic policy would do to the working class. You The Better was in part a response to that political time when the tables were turning and we seemed to be headed for where we are now. The house in a gambling game was my symbol for that capitalistic control.

Coyne: Going back to the game . . .

Beckman: Effort becomes strategy. The strategy is to develop a mixture of repeating what succeeded against the house, with what can be deduced about the house’s movement. To see chance, you have to see causality at work. We have to be able to see things that reverse before we can differentiate those events that don’t. In the film, the performers sing this jingle: “Chance makes so that things just can’t go back to where they once came from.”

Coyne: That’s such a great moment in the work.

Beckman: In You The Better, I was interested in this system of internal meaning—the motive for the game, the fantasy that is held out to the players by the game. First we try to find a reason for every chance event, believing that there is a hidden or innate reason why things happen. Trials in small amount reveal hidden meanings and prove that chance is there and exists. Trials in large amounts lead to some kind of prediction process, the ordering and conquering of chance. You can see the game mechanics, and you can see things as they are.

Ashley Bickerton confronts the randomness to find a system. He’s the guy at the center of the film who pulls away from the team and dialogues with them. He tries to find a hidden connection between successive trials and builds a theory based on his interpretation or belief in the hidden connections between these isolated events. When he can’t predict what color he will land on, he deduces that it will even out or reach equilibrium. As soon as he realizes that there is no way to integrate and affect the events in this game—that there is no causality between his action and that he can stack up the wins for the better—he discovers another system for controlling the game. Ashley’s monologue is the center of the film. Through this performance of trial and error, he shows a determination to create a system:

- The power of the spin

- The power within the player

- The preference of color

- A pattern of color preferences

- A belief in the distribution of the color pattern

- The ability to hit the color of preference.

Coyne: Your description of Ashley’s role in the film makes me think of our agency over work and our desire to feel that we possess it even when it’s lacking. Which leads into a related idea—I like this idea of work ethic you point out. What you are calling “work” for me was, at the time of this film, the desire for the team players to function as a unit and succeed with their strategy.

Beckman: The scene describes a person who steps out of the behavior of the group to analyze a problem, to logically break it down into small segments, and to put it back together so it works for him. What he actually is doing is getting his body in alignment with the temporal pattern of the event. This pattern seems logical to him, and for a few trials, he succeeds. But the pattern changes as soon as he starts to believe in his success. This is about presuppositions. We are governed by presuppositions; we look for logic and order. To do that, we break things down into units, look for patterns, and presuppose what the pattern will indicate for the future. What I have learned is that this is all false and that we actually can’t guarantee that anything we presuppose to be true really is. That’s why as an artist I prefer the language of the body and all the stories that can be told with it and from it, because I believe we operate biologically correctly.

Coyne: There’s societal critique in your work, specifically in You The Better and Cinderella (1986). In You The Better, the players hold the persona of white, working-class characters and their attire plays on these cultural stereotypes of the day in a way—I’m thinking of a young Billy Joel. I was struck by this active address toward a norm of the day coupled with the forward-thinking gender roles in Cinderella—this film was made thirty years ago yet feels contemporary.

Beckman: Although my work may contain a social critique, I am more directed by trying to understand the process of alignment between the self and the world, or situation one is in. The reason I use games is because players deeply analyze their purpose and are engaged in strategy building. The material for Cinderella came from my researching over three hundred versions of the story and using Vladimír Propp’s methodology to align fairy tales with common motifs. For me, Propp’s vertical indices are the progenitors of hyperlinks. Therefore, the structure of my Cinderella is similar to structures used by game developers, whereby the protagonist can fluidly move through different contexts and story levels by using or being used by a set of in-game icons. I wanted to find a folktale that could be a metaphor for women and technology and the history of industry. It was easy to overlay the symbols of the story with industrial and post-industrial motifs. In Cinderella the dress is this icon that is present through the whole film, although in a state of flux.

She has a set of choices:

Will you keep the dress?

Get to the Ball?

Dance with the right guy?

Drop a clue that you are?

Bring him home?

She chooses none of the above, but allows the game to play itself out. At the end of the film, Cinderella comments on the nature of her work, her femininity, and records a personal statement announcing her awareness that her mistaken identity has produced a cultural commodity. There have been times in my life when I felt that having a critique of a social stereotype was important to the work and to me. Hiatus (1999) is one instance of a critique on a set of gendered values. My early works and those I made in the 2000s do not feature this kind of overt critique. You have the Super 8 Trilogy (1978–1979) that dealt with Jean Piaget, identify formation, and a deep understanding of mental representation. In the 2000s, I was interested in responding to architecture, to building a new structure from a given architecture by playing and animating architecture. I discovered that through animating architecture I could expose the lines of force, energy, and symmetries inherent in the design of that space. The animation released design principles.

Mary L. Coyne is a curator and writer based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. She is a curatorial assistant at the Walker Art Center, working on Merce Cuningham: Common Time and pursing her research interests in multi-disciplinary performance practice. In 2014, Coyne opened a noncommercial art space, Pseudo Empire, in Brooklyn, New York, where she presented new projects by emerging and mid-career artists, developed programs, and produced publications. Coyne earned her BA in art history from the University of Southern California and her MA in art and curatorial studies from California State University, Long Beach, and completed her thesis on a revisionist reading of Jan Dibbets’ early practice and curated Split Moment, an exhibition that presented contemporary artists and choreographers who were working ideas around presence in performance. Coyne has published in numerous publications including Art Journal, Afterimage, Performa Magazine, and Journal of Curatorial Studies.

Ericka Beckman’s film work has been exhibited at festivals, museum and galleries around the world including exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington DC; the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN; the Tate Modern, London, UK; Kunsthalle Bern, Switzerland; Le Centre de Georges Pompidou, Paris, France; the Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna, Austria; Institute of Contemporary Art, London, UK; Le Magasin, Grenoble, France; Raven Row, London; Muzeum Sztuki, Lodz Poland; and has participated in four Whitney Biennials. Upcoming exhibitions include a solo project at Secession in Vienna (2017). Beckman’s films are represented in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, the Walker Art Center, the Broad Museum, Le Centre de Georges Pompidou, British Film Institute, Anthology Film Archives, the Stiftung Kunsthalle Bern, and the Zabludowicz Collection.