From Art Journal 76, no. 1 (Spring 2017)

Everywhere people danced and trembled. Everywhere people wrote on the walls of the city or communicated freely with total strangers. There were no longer any strangers, but brothers, very alive, very present. I saw people fucking in the streets and on the roof of the occupied Odeon Theatre and others run around naked on the Nanterre campus, overflowing with joy. The first things revolutions do away with are sadness and boredom and the alienation of the body. . . . The May Revolution dynamited the limits of “art” and “culture” as it did all other social or political limits. The old avant-gardist dream of turning “life” into “art,” into a collective creative experience, finally came true.

—Jean-Jacques Lebel

Around 9:00am on January 24, 2014, Maxym Vehera, an amateur artist, comes to Hrushevskyi Street in Kyiv, mounts his portable easel some one hundred yards from the riot police line, and spends five hours painting the scene of a street fight in progress.1 Black smoke from the burning barricade veils the sky, tear gas irritates the frosty air, a stun grenade explosion shuts all senses down. The canvas falls to the ground, into the mixture of snow and ashes. Vehera picks it up, wipes off the dirt, and continues to paint amid chaos. He endeavors to capture the moment, to document the event he never thought would ever happen in his city. Fifteen months later, the canvas would still adorn the wall in his apartment. Nobody has bought it. After all, this is not one of Francisco Goya’s Disasters of War. Yet when Vehera was painting that fight, mesmerized with its view, as if he could transform reality with his brush, Goya might have been reincarnated in him. In that moment of the now, art dwelled not in the canvas, but in the artist himself, in the performer and his performance.

This snapshot comes from the Maidan, otherwise known as the Euromaidan, the occupation protest in Ukraine between November 21, 2013, and February 21, 2014, following a long tradition of similar events, from the fresh Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street (OWS) back to the classic May 1968 revolution in Paris.2 From the historical perspective, these movements appear rather questionable in their outcomes. When they take protesters outside the law, endangering their lives and demanding sacrifices, occupations collapse, sometimes with extremely tragic circumstances. Nevertheless, they remain iconic models for precarious youth that rises against the fundamental injustice of social conditions throughout the world.

Occupations reject commodification, pedestals, and hierarchies, and they accept diversity, pluralism, and plurality. Relying on grassroots proliferation and genuine communalization, they generate the barrier-breaking environments Lebel describes in the epigraph of this essay, environments in which there are “no longer any strangers, but brothers, very alive, very present,” and where an “old avant-gardist dream of turning ‘life’ into ‘art’” comes true. Vehera’s story serves as an extreme example of how art provides people with an aesthetic experience even amid rebellious streets. Assemblages, installations, murals, posters, performances, happenings, and other art objects and practices inhabit the protest sites across decades, cultures, and state systems. Moreover, occupations themselves are “grand public works of process art with a cast of several thousand,” in Martha Rosler’s words.3

Academic art history has developed an interest in occupations, too. Scholars approach them from diverse theoretical perspectives under arbitrary rubrics of political, activist, social, protest, street, or occupy art. Thus, Joseph Esherick and Jeffrey Wasserstrom discussed the 1989 Tiananmen Square protest in Beijing as street theater, arguing that when there is no civil society, art becomes the only possible “mode of political expression.”4 Wu Hung, in turn, approached this protest as an “image making movement” and claimed a connection between the protest artworks’ ephemerality and the self-sacrifice of protesters.5 In recent years, Chad Elias has examined the Egyptian Tahrir revolution’s graffiti as a “playful and self-reflexive set of semiotic strategies” that aimed to “raise the consciousness” of the society.6 Yates McKee, in his writing on OWS, interrogated how an “artist as an organizer” and organized artists’ groups engaged in the “movement building practices” in the opposition to the “1 Percent” elite’s art world.7 Finally, W. J. T. Mitchell, while referring to OWS, Tahrir, Tiananmen, and Brian Haw’s camp in London, scrutinizes the space of the occupation both as a background (or “negative space”) against which a variety of verbal and visual images emerge and as an “iconic image” of a revolution itself.8

Acknowledging the insightfulness of these approaches, I focus instead on the interaction between an occupation and the artworks, embedded into its environment, as a dynamic system of semantic interdependence similar to the hermeneutic circle in which the whole and its parts might be interpreted only through mutual references. In other words, I argue not only that an occupation serves as a platform for artworks, but that through a dynamism of events it constructs and displaces their meanings, while artworks, respectively, not only reflect but also shape an occupation’s identity and thus indirectly orchestrate a dynamism of events.

This essay discusses the case of the Ukrainian Maidan, tracking its interdependence with artworks embedded into it, through two protest modes: non-violent resistance and the riot.9 In the Maidan’s early phase, grassroots artists anchored the protest’s identity as a nonviolent movement and, in this way, facilitated crowd control. Meanwhile, the protesters’ rejection of the state apparatus of power and suppressed fear of police violence provoked the fundamental aesthetic redefinition of the preexisting public space informing the occupation’s identity with the spirit of militancy. Eventually, artworks anticipated the tragic outcomes and reflected on the violent events. In the Maidan’s riot mode, militant objects revealed their aesthetic capacity, while artworks metamorphosed into weapons and participated in battles inspiring and protecting protesters. In the end, after the events played out their immediate dynamism, semantic codes congealed into the memorializing singularity of the grave.

Nonviolent Resistance

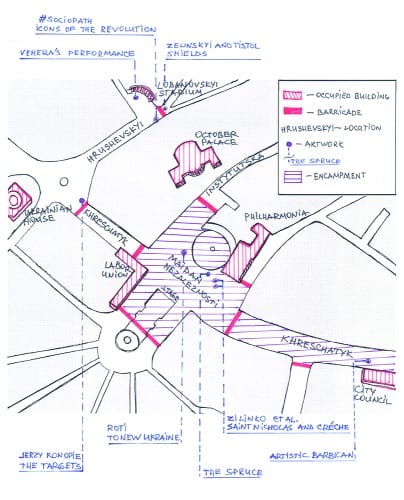

On November 21, 2013, the government of Ukraine abruptly suspended the preparation for the European Union Association Agreement and thus impeded the country’s decades-long drift from the oligarchic post-Soviet regime into the Western free-market democracy. In response, a few hundred young women and men occupied the Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv to manifest their dissent. With tents and megaphones, the protest stood its ground for nine days until fully armed riot police “cleaned” the place. After videos documenting the cruel beatings of the protesters, who were mostly undergraduate students, were circulated through the media, about a million people flowed into the streets of Kyiv. They occupied several public buildings around the square, barricaded the streets that lead to it, and set up an encampment, providing free shelter and food for everyone.

In the beginning, the Maidan developed as a nonviolent resistance movement rooted in the memories of the Orange Revolution (Kyiv, 2004), another occupation that with songs and without militancy had surfaced in the same square.10 Notably, the first structure the protesters erected at the site in 2013, even before the barricades, was the stage, an elevated area equipped with speakers and lights. It became the focal point for the dissemination of peaceful messages. The pop star Ruslana, the winner of 2004 Eurovision Song Contest, took charge of the microphone. Spending long hours on the stage each day, engaging, communicating, informing, and entertaining the audience, she became a living symbol of the occupation.11 Other Ukrainian singers and bands also performed on the stage, and on some nights the Maidan was more reminiscent of a music festival than a protest.

Gradually, political parties took the stage under their control. They used it for political performances featuring passionate speeches softening the soil for the upcoming elections. Condemning the ruling regime, politicians constantly warned protesters not to succumb to violence. As Esherick and Wasserstrom have pointed out, political theater either opposes the hegemony of the authorities or defends the elite’s position “against attacks from below.”12 The Maidan’s stage seemed to combine both functions: it manifested dissent but at the same time facilitated crowd control, thereby securing the political class from unexpected turnover.

On the other hand, protesters supported the nonviolent ethos not only because of the manipulative propaganda but also because it resonated with their moral values. Students and educated middle-class professionals made up the majority on the square. As lawful citizens, they, in general, rejected violence as a method of struggle, even if police used violence against them. Independent grassroots actors from this social environment willingly rendered the Maidan’s identity as a nonviolent movement, channeling their peaceful self-image into the global media space.

Markian Matsekh, an IT worker from the city of Lviv, staged one of the earliest performances. On December 5, 2013, together with his friends, he painted a piano in the blue and yellow colors of the Ukrainian flag, brought it to Luteranska Street in front the riot police line, and played Frédéric Chopin’s Waltz in C-sharp minor, op. 64, no. 2.13 Andrij Meakovsky’s photograph of the event went viral on social media, resonating with the Tank Man, a photograph of unknown protesters who alone attempted to prevent tanks from entering Tiananmen Square in 1989.14 Performing Chopin for the police, Matsekh, as he explained in interviews, sought to persuade them that the protest was peaceful. Another group of creative activists came up with a sticker series EuroMaidan is . . . . They appropriated the design from Kim Casali’s commercial comics Love is . . ., but filled it with humorous original snapshots from the occupation. The designer Olexandra Navrotska recalls that the group used a shared Google Docs file to accumulate ideas; the journalist Vasylyna Duman, a leader of the group, made a primary selection, and then Navrotska made drawings from the ideas.15 Printed in thousands of copies, the stickers disseminated the image of the Maidan as a peaceful community around the encampment and beyond. In a similar spirit, the Strike Plakat, an anonymous, collaborative graphic design group, organized the mass production of political posters.16 High-resolution files were published online so that everyone could print and bring them into the streets. The group’s most famous poster (with its iconic visual vocabulary reminiscent of ACT UP’s 1986 Silence=Death) depicts a drop falling into the ocean, signifying the personal contribution of each protester to a common peaceful cause and the protest’s ability to embrace everyone.

This Maidan ocean of students, middle-class people, and politicians was also populated with religious communities, predominantly Christians of the Byzantine Rite (Ukrainian Greek Catholics and Ukrainian Orthodox). Kyiv’s churches and monasteries opened their doors for protesters, providing them with places to sleep and rest. Collective prayers and vigils were regularly held on the square, while the figure of a priest became one of the striking features of the occupation. Religious images entered the encampment along with the believers. Priests brought icons to the stage; one of the tents on the square housed a Christian chapel with a small iconostasis; and spontaneous icon production emerged within the encampment.17

In the beginning of December, the artists’ collective from Lviv even mounted two larger-than-human-scale religious installations in front of the stage: the freestanding, double-sided (in green and red), cutout figure of Saint Nicholas, and the Crèche, a model of a stable with the Nativity scene. The artists constructed the figures from particle board bought in a local supermarket and then painted them in brightly luminous colors with thick black outlines, in the naive nineteenth-century folk style of Ukrainian Carpathian icons. According to Roman Zilinko, a leader of the group, its members aimed to introduce “a native, ethnic, home-brewed element” into the place of the occupation, and to enlighten it with a spirit of the upcoming holiday season.18 The artists painted Saint Nicholas on site in the Square, attracting observers to the unusual spectacle, while the installation of the Crèche, engaging helping hands from the crowd, developed into an hours-long participatory performance.19 Because of Soviet atheistic politics, the medieval tradition of the crèche has been eliminated from most regions of Ukraine, and thus many protesters were uninformed about the symbolic meaning of this object. Eventually, however, many came not only to take selfies but also to pray and acknowledge its religious function. The religious installations infused the Maidan with the spirit of a religious procession, turning the protest’s heat down.

Taken as a whole, the artistic practices and objects in the first weeks of the Maidan both reflected its dominant nonviolent ethos and established that ethos as dominant. Along with the “controlled” shows at the concert stage, a focal point of the encampment, the independent grass-roots artists’ collectives revealed their agency, too. Appropriating various visual devices ranging in their origins from popular culture to religious iconography, they enlightened the protest with joyful aesthetics.

This peaceful mode of protest, however, so lavishly accompanied with artistic utterances, constitutes only one side of the coin. The arrogance of the regime and the radicalization of the protesters created an explosive strain that inflamed a full-scale riot with street fights and deaths. Though it took almost two months to transform a nonviolent resistance movement into a riot, the prologue to this inversion manifested rather early, taking the Maidan’s art captive with grimmer overtones.

Invocation of Riot

Early in the morning on December 8, 2013, the feminist artist Maria Kulykivska together with Ivan Sautkin, the video director of the studio Babylon’13, secretly penetrated the PinchukArtCentre gallery in Kyiv.20 It was Sunday. The Maidan protesters ran another peaceful rally on the square, but Kulykivska decided to rehearse a different performance. She undressed, took a sledgehammer, and smashed her artwork on view in the gallery, an installation of eight-foot-high pillars constructed with self-produced salt bricks.21 In her semantic code, they represented a vertical structure of the patriarchy, the systems of oppression. She wanted to bring it down, to make the structure horizontal, to envision the notion of equality for all, the central idea she encountered at the Maidan.

That evening, while driving, Kulykivska noticed a crowd gathered around the monument to Vladimir Lenin on Taras Shevchenko Boulevard, a few blocks from the square. In 1939 the sculptor Sergei Merkurov had created an eleven-foot-high granite portrait of Lenin for the Soviet pavilion at the 1939–40 New York World’s Fair. In 1946 it was mounted on a twenty-foot-high pedestal in Kyiv. Now, in December 2013, its story came to an end. Kulykivska stopped the vehicle, grabbed a sledgehammer from the trunk, and ran toward the spot. In front of her eyes, the statue fell from the pedestal, raising a war cry over the crowd. Someone whipped the hammer from her hands, and the next moment it smashed into the red Karelian granite.

This act contradicted the Maidan’s nonviolent identity, and the majority of the protesters condemned it as a provocation that aimed to split the movement. While this critique was certainly accurate, the act of destruction is not unusual for these protests. Iconoclasm, not necessarily physical but at least symbolic, is present in almost any occupation. Even on Tiananmen Square, the protesters dripped paint on the giant portrait of Mao Zedong at the Gates.22 Such incidents happen not only because a crowd mentality tends to foster vandalism, but also because the overall perception of a public artwork depends on the political message it conveys.

In the eyes of the Maidan protesters, Lenin’s monument was not just a sculpture, a portrait of a historical figure, but a symbol of the system they revolted against. Thus, in their attitude to the monument they manifested their rejection of the system. The Maidan rose up against the post-Soviet state apparatus of power, its fundamental corruption blended with hypocritical officiousness, its bribes, and the abuse of public interest for self-enrichment, against the neocolonialism of Putin’s Russia attempting to bind Ukraine within its circle of influence. Twenty-two years after the Soviet Union had died, Lenin’s monument still towered in Kyiv as the ever-present image of the Soviet colonial power that had victimized Ukraine in the past: through famine-genocide in 1932–33, mass repressions in the country’s west before and after World War II, and many other atrocities. Even after Ukraine declared independence in 1991, that power had never been overthrown completely. The upper class formed by the members of the Communist party, the nomenklatura as the Russian dissident Mikhail Voslensky called it, through the politics of privatization has brought public property into its hands and preserved control over the state. Lenin’s ideology was forgotten, but his party’s hegemony over the society persisted, and Lenin’s monument in Kyiv provided visual proof of the fact.

The demolition of the monument was not an art performance, yet it still provides a key for understanding how the occupation’s political agenda manifested itself in the interaction of the protest art with the preexisting public space. I suggest that this interaction, as was the case with Lenin’s monument, was determined by the notion of rejection. Just as the Maidan with its overall empathy and communalization dismissed the selfishness and corruption of the state apparatus of power, so the Maidan art with its community-based mode of production and sincerity rejected the pretentious officiousness of the preexisting space, which sought to control the voices of the public. The Maidan art set a kind of counterenvironment opposed to this control, both liberating the people and, in Chantal Mouffe’s words, transforming the square into a “battleground where different hegemonic projects are confronted, without any possibility of final reconciliation.”23

Indeed, the preexisting space of the square reflected the malformed nature of the post-Soviet state system, deeply rooted in its dark colonial past and somehow camouflaged with the rhetoric of the “national rebirth.” In Soviet times, the square’s basic semicircle of monolithic, mid-twentieth-century, Stalinist, classicist buildings faced the Monument to the Great October backed by the Hotel Moscow on a hill. In 1991 that monument was removed, but the dull atmosphere never vanished. A decade later, a fundamental reconstruction of the square began on the eve of 2001 to eject the “Ukraine without Kuchma” protest from the city’s center. It resulted in a drastic segmentation of the inner space with diverse disconnected objects including the enormous glass domes of the trade center, a globe indicating distances from the major world capitals to Kyiv, a replica of the eighteenth-century city gates with the statue of Archangel Michael imposed on top, a monument to the semi-legendary medieval founders of Kyiv, a statue of a Cossack sitting next to his horse, and, amid all of this, almost in the same place where the October monument once stood, the colossal Monument to Independence featuring a figure of the winged Berehynia (a Slavic goddess), reminiscent of the Nike of Samothrace, imposed on a one-hundred-fifty-foot-high Corinthian column supported by a small building with arched openings on each side.

With the beginning of the Maidan protests, this space underwent a surreal alteration. The most substantial change came with the barricades, an enormous assemblage constructed from salvaged urban materials, which, in order to secure protesters from the police violence, enclosed the square in early December 2013. The barricades’ explicit aesthetic significance was constantly acknowledged and discussed;24 yet I would like to stress their role in the rejection of the preexisting layer of the public space. Walls, sometimes up to fifteen feet high, formed with sand- and snow-filled bags, and built up with urban junk, were elaborated with barbed wire, vehicle tires, models of antitank obstacles, and brightly painted metal barrels tagged with radiation warning signs. The most impressive barricade on Instytutska Street even incorporated the overroad metal footbridge lavishly adorned with flags and banners, one of which read: Laskavo prosymo do Pekla (Welcome to Hell).

The barricades transformed the square into a fortress. The new identity of the place was underlined with the protest “tower,” a metal cone more than one hundred foot high composed of vertical piers bound by horizontal circles and subsumed in a miscellaneous carpet of flags. Its shape evokes striking analogies in the history of political art, such as the Peace Tower mounted by the Artists’ Protests Committee in Los Angeles in 1966.25 The Maidan’s tower, however, appeared not as a result of deliberate artistic intent, but rather as “accidental” art. Its framework came from an unfinished city Christmas tree which the authorities installed on the square each year for the holiday season. Protesters even named it accordingly—the Yalynka (the Spruce). But when they expropriated it to manifest their identity and demands, decking it out with banners and flags, they completely reframed its meaning. They transformed it into an iconic antimonument that with its raw power along with the barricades aesthetically opposed the polish of official public art and thus manifested their revolt against the state apparatus of power.26

The metaphor of the Maidan as a fortress did not go unnoticed by professional artists, who reinforced it with the Artistic Barbican, a rectangular structure built from wooden pallets and particle board in front of the occupied City Hall on Khreschatyk Street. Its architect, Dmytro Zhyla, initially conceived it for a utilitarian defensive purpose (its name refers to a type of fortification), but, eventually, it evolved into an art space, vulnerable and ephemeral.27 The Barbican served as a venue for poetry readings, lectures, and violations of the zero-tolerance alcohol law adopted on the Maidan. It also hosted a permanent exhibition of posters reproducing works by the Kyiv-based artists Ivan Semesiuk, Olexa Man, and Olexander Yarmolenko, which ironically combined folk-art images with skulls, guns, Molotov cocktails, and the fluttering black flags of Anarchy.28

The postapocalyptic cyberpunk fortress, protected with barricades and dominated by the rebellious tower, contradicted the Maidan’s early identity as a nonviolent resistance movement. Contrary to the peaceful rhetoric, channeled from the stage and reflected in art practices of independent actors, the fortress prepared protesters for battle. Collectively conceived in reaction to police violence as a defensive structure, it impregnated the protest’s identity with romanticized militancy and suppressed the awareness of the consequences a violent riot might engender.

One of the last significant artworks of the nonviolent phase of the Maidan, a sculpture by the French-born street artist Roti, signaled the upcoming conflict. From the standpoint of iconography, this work was a parapraxis, a Freudian slip, that revealed the artist’s unconscious anticipation of the tragic outcome in the sequence of events.

In the evening on January 7, 2014, the day Christmas is celebrated in Ukraine, an unusual procession entered the square: a group of women from the Freak Cabaret Dakh Daughters moved and sang in a slow, meditative rhythm, accompanied by a heavy truck carrying a massive five-ton marble block. Roti himself helped workers to deposit the piece at the side of Instytutska Street, twenty yards from the Spruce. For the two previous weeks, he had been in a workshop in an industrial area of Kyiv, working for long hours with a high-voltage power sander, a hammer, and a chisel. Now, the time had come to show his work to the public.

Roti’s sculpture represents a female figure floating in water: only face, palms, and feet are visible above the surface, as if her body emerges from the deep. Roti inscribed the artwork Noviy Ukraini (To New Ukraine), cutting the letters on the narrow facet of the block below the figure’s feet. In the documentary video about its creation, the artist explains that the sculpture was his gift to the Ukrainian people, a kind of a “tag” that will persist for many years to remind them about this “crazy moment, crazy and beautiful at the same time.”29 According to the video’s narration, the sculpture symbolizes “Ukraine as it emerges from its past and frees itself from a regime that has kept its people from breathing for far too long.”30

Clearly, the artist was making a reference to the classical tradition of female allegories, resonating with the iconography of other recent occupations as well. As Mitchell observed, since “the whole tactic of nonviolence has an inherently feminine and feminist connotation,” the iconic image of a nonviolent protest inevitably would be “centrally focused on women.”31 These feminine images, however, deliver divergent messages. In particular, Mitchell contrasts the Adbusters’ Ballerina dancing on the Wall Street Bull near the OWS site with the viral photo Woman in the Blue Bra, whose subject was beaten by police at Tahrir Square in Cairo, claiming that the former represents “triumphal defiance,” while the latter stands for “abjection, humiliation, and police violence.”32 Agata Lisiak has elaborated this contrast into a binary opposition between a “revolutionary ideal” and a “revolutionary failure.”33

Because of its horizontality, Roti’s sculpture is reminiscent rather of the Woman in the Blue Bra, the humiliating image of “failure.” Its iconography is also clearly related to John Everett Millais’s painting Ophelia, (1852) and other artworks depicting death, as Juan Soriano’s The Dead Girl (1938) or even Andrea Mantegna’s Dead Christ (ca. 1480). The marble block itself recalls a sarcophagus, while the Dakh Daughters performance, framing its transportation to the square, clearly emulated a funeral procession with a cortège carrying the coffin. As further events revealed, in that sculpture, the artist subconsciously embodied the vision of a protester’s dead body lying on a street.34

Blood, Fire, Chaos

Roti’s sculpture arrived on the square on Christmas, and the fire of riot ignited on Epiphany. On January 19, 2014, about ten thousand protesters abandoned a peaceful rally on the square and marched toward the Parliament demanding a recall of the “dictatorship laws.” Illegitimately passed few days before, these laws significantly restricted human rights, including the rights of free speech and of protest.35 Down on Hrushevskyi Street, riot police barricaded the road with buses and attempted to “calm down” the crowd with tear gas, stun grenades, and rubber bullets. Protesters replied with stones, Molotov cocktails, and petards. On the fourth day of the clashes, during the violent police counterattack, three protesters were killed.

The street artist Jerzy Konopie reacted to these events with an installation of nine full-scale human silhouette targets fixed to the wooden poles in front of the barricade protecting the entrance to Khreschatyk from Hrushevskyi Street, three hundred yards from where the first victims had been shot. Some of the targets wore the colored vests of journalists and medics, while others were decorated with blue and yellow ribbons, the colors of the protest. The artist pierced the “bodies” of the targets with holes in imitation of the bullet holes in the real bodies of the protesters.

The very idea of a target as an artwork was not new. We may recall Jasper Johns’s Target series or more recently Harun Farocki’s video installation Eye/Machine, which deals with the image-recognition technology used in smart-bomb cameras to envision victims through the eyes of the attackers.36 Yet Konopie’s project engaged an entirely different relationship between image and reality. When he located The Targets on the site where the real victims suffered from the real shots, he embedded the artwork directly into the reality it referred to. Consequently, the artwork appropriated that reality to itself, extending the experience of violence against the protesters’ bodies into a permanent vision at the very site where the violence took place. It explicitly articulated the protesters’ image as victims of violence, embodying the intangible sense that everyone on that street was now reduced to a target.

The next morning, the artist found his artwork slashed to pieces. He presumed that the defenders of the barricade did this; they made some controversial comments even when he installed it.37 Of course, these targets could have attracted some negative reactions from the police marksmen, but the rage with which they were demolished suggests an extremely emotional reaction. Arguably, protesters destroyed the artwork not for security reasons but for the message it conveyed.

This act of iconoclasm directed against yet another artwork calls into question the relevance of art to the street fight. Indeed, when you stand in the dark in front of a police line, scanning the space behind the shields for the tiny lights of shots, waiting for a grenade or a rubber bullet to hit you in the next moment, an artwork seems to be the last thing you need by your side. Nevertheless, under the extreme conditions of the Maidan riot, the meaning of objects and practices tended to invert, and artworks appeared to be relevant, emerging even from weapons.

When, in 1984, Lucy Lippard suggested that “the Trojan Horse was the first activist artwork” she was writing metaphorically: activist artworks treacherously penetrate the “beleaguered fortress” of the “art world” to capture it from within and to manifest effectively their political agenda.38 While Lippard did not refer to occupations, variations of the Aeneid’s horse—equivocal objects with dual functions—inhabit the rebellious streets of our times. For instance, on the second day of the clashes, the Maidan protesters deployed a full-scale catapult on Hrushevskyi Street. When this twelve-foot-high wooden construction on wheels—a functioning mechanism designed to throw objects—arrived, the crowd greeted it with enormous enthusiasm. Despite the fact that it failed as a weapon (the loading time was too long, while the angle of the shot was insufficient), it succeeded as a kinetic sculpture. Each of its shots presented a spectacle with an undefined outcome, entertaining and encouraging the protesters.39 Another object of that type, called the “TV-set,” combined a wooden construction with a high-tech projection.40 Originally intended for “psychological operations” against the police, it instead functioned as a mysterious multimedia installation, shining amid the dark street. The armor of the individual protesters also underwent a similar transformation of function. Protesters decorated safety helmets and shields with intricate graffiti featuring folk ornaments, inscriptions, and even more elaborate scenes.

This folk art also inspired two Kyiv-based artists, Andriy Zelinskyi and Oleh Tistol, to organize a “factory” to supply fighters on Hrushevskyi Street with special defensive equipment. As Zelinskyi explains, for many weeks their social support of the protest “felt somehow completely detached” from their “work as artists,” so after the fight began, they started to explore how to contribute with objects that were both useful and at the same time artistic.41 Since Tistol had stored some plywood in his workshop, they decided to use it for shields. The artists cut out rectangular boards and then equipped them with notches and straps. On the front of each shield, they stenciled in black a smiling face of president Viktor Yanukovych in the fashion of Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q., combining it with a monogram of a strong Slavic obscenity equivalent to the English “fuck off.” Brought to Hrushevskyi Street, these shields saw action in the clashes, and fighters also displayed them on the barricades as the sign of their courage.

Of course, one may reasonably doubt whether we should label such objects as artworks. Zelinskyi himself noted the ambiguity of the definition: “When Ala Rybitska [an art activist from the city of Dnirpo] with her friends lay down on the railway to stop the army train [with reinforcements against the Maidan] did they stage a flash mob? Well, then, I have pretended to be a street artist. Nevertheless, we produced these shields because we hoped they would protect people. Perhaps they were not so refined, but we tried it hard. The picture on a shield was secondary, not accidental, but secondary.”42

To escape this slippery terminological trap, I will adopt the approach Amy Mullin has used to justify the notion of activist art. She borrowed the term from Lippard to define a kind of art that was not just politically “concerned” but politically “involved,” which implies a political action and “actively seeks public participation” both in the process of its creation and in its perception.43 Conservative critics have constantly dismissed activist art for privileging politics over aesthetics and for aligning itself with propaganda. Rejecting such “misguided” accusations, Mullin proposes to acknowledge that just as artworks may “imaginatively explore patterns, colors, shapes, the movement of bodies” they may also “imaginatively explore moral and political ideas,” too, and, as far as this exploration remains “imaginative,” activist artworks possess an artistic value.44

Projecting this transcendent definition of art onto riot conditions on Hrushevskyi Street, we may assume that, because such objects as the catapult, “TV-set,” and Yanukovych shields explored the militancy imaginatively and produced explicit aesthetic effects, their artistic significance should be acknowledged despite the initial intentions of their creators.

As we shall see further, this transcendence of function went both ways: not only did weapons become artworks, but artworks also became weapons. Consider one of the most striking examples: #Sociopath’s stencil mural Trilogy: Icons of Revolution, painted on Hrushevskyi Street on February 10, 2014. This three-part mural presents portraits of the major poets in the history of Ukrainian literature: Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861), Lesia Ukrainka (1871–1913), and Ivan Franko (1856–1916). The black figures in black frames on a white background occupied narrow spaces between the windows on the building behind the foremost barricade. The artist used canonical portraits of the poets from banknotes and textbooks, combining them with attributes of the street fighters: a red scarf camouflaging the face, a blue respirator to combat tear gas, and an orange construction helmet protecting the head from police truncheons. Diagonal crosses made of burning Molotov cocktails, the tools of riot, adorned each image on both sides.

This drastic juxtaposition between officiousness and rebelliousness can be read in light of the global street-art scene’s indulgence in ironic contrasts. For instance, #Sociopath’s Lesia Ukrainka wearing a respirator matches well with El Zeft’s poster of Nefertiti wearing a gas mask shown at the Uprising of Women in Cairo on February 12, 2013, while the whole Icons series closely relates to works such as Banksy’s image of Mona Lisa with a rocket launcher, or the portrait by Mr. Brainwash (who might be another Banksy avatar) of Barack Obama wearing a Superman suit.45 In fact, #Sociopath even acknowledges that his initial inspiration as a street artist came from Banksy.46

Still, these parallels do not fully define #Sociopath’s mural as an artwork. While Icons relies on street art’s deployment of an appropriated image and shares the same illegal mode of production and the personal risk for the artist, his triptych differs in its core motivation. Ellen Handler Spitz in her article on New York’s subway car graffiti identifies the force behind a street artist’s production as “an intense desire on the part of the crew or clique to gain recognition from an indifferent world.”47 Though #Sociopath inscribed his nickname on the portraits, he did not seek recognition as a street artist. Instead, the project became for him an act of empathy with the protesters. A few days before he conceived his mural, a rubber bullet had brought him down from a barricade. Protesters ran to him, checked his injuries, helped him to get on his feet, and shared with him a happy moment of relief. He realized in that moment “that you are not alone, that you are the people.” Thus #Sociopath decided to channel that sentiment into the artwork that would help fighters on Hrushevskyi Street withstand the hardship of riot, to “encourage them keep going forward, despite blood and death.”48 He did not depict political leaders or warlords, but poets whose poetry the protesters remembered from childhood, whose significance the people acknowledged despite political disagreements.

The artist supplemented the images with carefully selected quotations. In doing so, he aimed to “synchronize the poetry lines with the atmosphere of the Maidan,” to make people read the images “directly.”49 Thus, Shevchenko’s “Red battle flames are safe for the reckless” referred to the flames of the burning tires on the barricades; Lesia Ukrainka’s “[Only those] who will free themselves become free [indeed]” explained the agenda of riot; and Ivan Franko’s “Our whole life [is] war” manifested the new identity of the protest centered on a warrior ethos.50

More than a century ago, these poets called Ukrainians to self-awareness as a modern nation, and now #Sociopath resurrected their images and words in the context of the Maidan. He brought them back from the motionless pedestal of history into the dynamism of the rebellious present, making them look like the protesters who were hiding their faces behind scarfs, wearing respirators and gas masks, and protecting their heads with helmets. In the burning fires of riot, on the wall behind the barricade, these Icons stood on the forefront together with the protesters.

A week later, on February 18, 2014, police launched a final assault on the fortress of the Maidan. They smashed the resistance on Hrushevskyi Street, broke through the barricade on Instytutska Street, set fire to the Labor Union building hosting the Maidan’s hospital, and burned half of the encampment to the ground. Police and criminals, hired by the regime, killed dozens of protesters. During the siege, which lasted for three days, the artworks were dragged into the dreadful turmoil, too. The Artistic Barbican and even the Crèche metamorphosed into shelters for the production of Molotov cocktails. Next to infant Jesus in the manger protesters were pouring gasoline and motor oil into bottles. Meanwhile, the figure of Saint Nicholas was brought onto the barricades.

Olexander Bryndikov, an artist who participated in the Crèche project in December, describes what he witnessed in February: “Everything was burning while near the Crèche [Molotov] cocktails were produced. Smudged in soot, people prayed, then grabbed the next box packed with bottles plugged with cloths soaked in gasoline, and trudged onto the barricade. And then a real miracle happened. I saw Saint Nicholas at the burning barricade and said goodbye to it in my heart. They [protesters] used it as a shield defending themselves from attackers, but in the morning a friend found it undamaged lying on the burned ground.”51

This story resembles medieval accounts of icons protecting besieged cities from attackers. To mention just one example: the seventh-century Byzantine author Theodeore Synkellos describes the procession with the acheiropoietos (“not made by human hand”) icon of Christ that took place on the walls of Constantinople during the battle with Avar. He claimed that the Patriarch, having raised the icon in his hands, showed it to the enemies “just like an invincible weapon.”52 In the same manner, the protester raised St. Nicholas on the burning barricade on the square, just as #Sociopath mounted his Icons on the wall on Hrusheskyi Street. The context of riot activated the Maidan artworks as “invincible weapons,” facing the battle, protecting and inspiring protesters, dying and miraculously surviving with them.53

Entombed

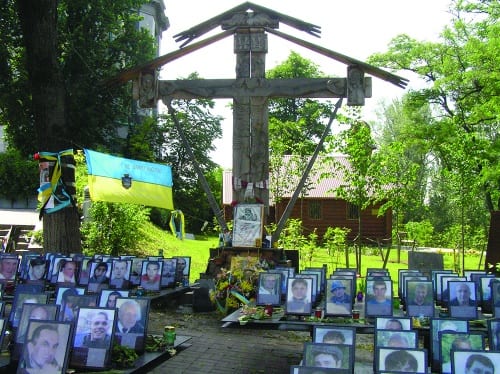

On the morning of February 20, 2014, snipers and retreating police shot forty-six protesters trapped on Instytutska Street, bringing the total number of victims to one hundred. The next day, exactly three months after the initial protest had begun, president Yanukovych and his clique fled the country, and the parliament appointed a new government while also announcing presidential elections.

As the Maidan mourned the Heavenly Hundred—the victims killed in these days—its art changed its meaning once again. A seemingly endless human river carried flowers to Instytutska Street, where the site was lit with thousands of candles. Coffins arrived on the square for the public mourning. Roti’s sculpture, risen from ashes, covered with black tears left by morning rain, harvested the sorrow. People laid candles and flowers directly on its surface as if on a tombstone. Its inscription, To New Ukraine, obtained an overtly sepulchral denotation.

In the following months, the encampment shrank in size until it completely vanished in July 2014. The new city authorities decided to clean the site: the Spruce, the protest tower, was brought down. To preserve the Artistic Barbican, the artists relocated it to the commercial art forum at Kyiv’s Expo-center. The few Yanukovych shields that somehow survived the street fights toured abroad with the exhibition of protest art and then returned to Tistol’s workshop.54 The nongovernmental activist group moved the Crèche, Saint Nicholas, and Roti’s sculpture, which someone “restored” with white paint, into storage to preserve them for the future Maidan Museum.55 The Icons of Revolution remain on Hrushevskyi Street. They frame the windows of a fancy furniture shop and watch expensive luxury cars rush into the government district.

Deprived of the occupation, the square has returned to its previous status. The mixture of Stalinist architecture with post-Soviet official monuments has reasserted itself once again. Nevertheless, consequences of the clashes remain discernible even three years after the events. The burned walls of the Labor Union loom behind the advertising banners that fail to conceal them. From the foot-steps of Instytutska Street up the hill, to the place where the barricade with the “Welcome to Hell” banner once stood, photographs of the victims of the Maidan, framed by bricks, have been arranged into a DIY memorial route with a cross in the middle. Further, at the site of the mass shooting, photos attached to the trees, candles and flowers on the pavement, small assemblages of bricks, shields, helmets, and tombstones mark the spots where protesters died. Finally, at the top of the hill, at the entrance to the government district, on the side of the road we are confronted with Golgotha, a twelve feet high wooden Crucifixion with dozens of victims’ photographs in black frames deposited in front of it. We read inscriptions, on the flags, on the banners, on the tombstones: “Heavenly Hundred,” “Heroes never die,” “We see everything.” Their faces remain with us.

The system of interdependence between the occupation and its art has collapsed along with the collapse of the occupation. There is no more dynamism of events to imbue the meanings of its artworks with continual fluidity. Conceived as site-specific, attached to the physical and discursive environment of the occupation, away from these places and events the artworks became shadows of themselves.56

Now, if we seek the Maidan art, its material relics are not the place where we find it. Instead, I suggest, it exists in what Joseph Beuys has called a “social sculpture”: not in Siegfried Kracauer’s “human ornament,” for which thousands of bodies are joined in a mass performance in service to autocracy, but in Beuysian “social sculpture,” an “invisible substance” that with its “resurrective force” shapes a new “healed” social body.57 This art is an energy that invisibly emanates from the artworks into the society, and after its source ceases to exist, it continues to dwell among the people.

The epigraph is from Jean-Jacques Lebel, “Notes on Political Street Theatre, Paris: 1968, 1969,” TDR The Drama Review 44 (Summer 1969): 112 and 113.

I have given talks on art of the Ukrainian Maidan at several venues, including the CAA–Getty International Program colloquium at the CAA Annual Conference in New York, February 2015. I am grateful to the organizers and audiences for their questions, feedback, and encouragement. This essay is indebted to Rebecca M. Brown and anonymous reviewers for Art Journal, who with their useful criticism and insightful suggestions guided me through revisions. Many thanks to Renata Holod, Janet Landay, John Tain, Noit Banai, Márton Orosz, Oksana Schocher, George Lewycky, and Halyna Kohut for advice and other support. Thanks also to my interviewees, to photographers who provided images for this essay, and to all artists and activists of the Maidan.

Nazar Kozak is a senior research scholar in the Ethnology Institute at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. He has also taught art history in the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv. His current research focuses on post-Byzantine iconography and contemporary activist art. Presently, he is a Fulbright scholar in the Ukrainian Museum in New York. E-mail: knb_ua@yahoo.com

- Maxym Vehera, telephone interview with the author, April 10, 2015. ↩

- “Euromaidan” literally means “the Eurosquare” and derives from the name of the central square in Kyiv, Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or “Independence Square.” In this essay, I will use the shorter term “Maidan” to refer to the occupation. In Ukraine, it was the fourth occupation in the last three decades, after the student hunger strike called the “Revolution on Granite” (1990), the “Ukraine without Kuchma” mass protest (1999–2000), and the Orange Revolution (2004). On the Maidan as political movement, see, David R. Marples and Frederick V. Mills, eds., Ukraine’s Euromaidan: Analyses of a Civil Revolution (Stuttgart: Ibidem Press, 2015). ↩

- Martha Rosler, “The Artistic Mode of Revolution: From Gentrification to Occupation,” e-flux journal 33 (March 2012): 15, at http://worker01.e-flux.com/pdf/article_8950961.pdf, as of February 12, 2016. ↩

- Joseph Esherick and Jeffrey Wasserstrom, “Acting Out Democracy: Political Theater in Modern China,” Journal of Asian Studies 49, no 4 (1990): 835–65. ↩

- Wu Hung, “Tiananmen Square: A Political History of Monuments,” Representations 35 (Summer 1991): 107–14. ↩

- Chad Elias, “From Street to Screen: Graffiti, New Media, and the Politics of Images in Post-Mubarak Egypt,” in Walls of Freedom: Street Art of the Egyptian Revolution, ed. Basma Hamdy and Don Karl (Berlin: From Here to Frame, 2014), 89–91. ↩

- Yates McKee, “The Arts of Occupation,” Nation, December 15, 2011, at www.thenation.com/article/165094/arts-occupation, as of July 4, 2015; McKee, “Occupy Response,” October 142 (Fall 2012): 51–53; McKee, “Debt: Occupy, Postcontemporary Art, and the Aesthetics of Debt Resistance,” South Atlantic Quarterly 112, no. 4 (Winter 2013): 784–803; McKee, “The Weird Red Thing: #OccupyWallStreet, Site-Specificity, and di Suvero’s Joie de Vivre,” in Broken English, ed. Julieta Aranda and Carlos Motta (New York: Performa, 2011), at http://11.performa-arts.org/images/uploads/pdf/BROKEN_ENGLISH.pdf, as of July 21, 2015. ↩

- W. J. T. Mitchell, “Image, Space, Revolution: The Arts of Occupation,” Critical Inquiry 39, no. 1 (Autumn 2012): 8–32. Brian Haw was a peace protester who lived in Parliament Square in central London for some ten years (2001–10). ↩

- Although my findings are primarily based on the experience of the Ukrainian Maidan, comparative data suggests that, with some adjustments, they can be applicable to other occupations, too. The striking iconographic and functional analogies between artworks in different occupations should not be considered in terms of borrowing, but rather as evidence of how, in Reiko Tomii’s words, “contemporaneity frequently manifests itself through similarity in form, idea, and strategy.” Tomii, “The Discourse of (L)imitation: A Case Study with Hole-Digging in 1960s Japan,” in Globalization and Contemporary Art, ed. Jonathan Harris (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 350. On the art of the Maidan see Natalia Usenko, “Political Issues in Contemporary Art of Ukraine,” Journal of Education Culture and Society 2_2014 (2014): 180–92; Olesia Avramenko, “Vohon’ lubovi (Fire of love),” in Antin Mukharskyi, ed., Maidan Revolutsia Dukhu (The Maidan: Revolution of spirit) (Kyiv: Nash Format, 2014), 244–51; Alisa Lozhkina, “Iskusstvo na barrikadah: Maidan glazami khudoznikov (Art on barricades: Maidan through eyes of artists),” Art Ukraine, February 6 and 7, 2014, at http://artukraine.com.ua/a/iskusstvo-na-barrikadah-maydan-glazami-ukrainskih-hudozhnikov-ch1, and http://artukraine.com.ua/a/iskusstvo-na-barrikadah-maydan-glazami-ukrainskih-hudozhnikov-ch2, as of February 12, 2016; Natalia Moussienko, Mystetstvo Maidanu (Art of the Maidan) (Kyiv: Vydavnyctvo, 2015), 9–10. Moussienko’s book also includes the text of her previously published article in English. ↩

- On the Orange Revolution, see Adrian Karatnycky, “Ukraine’s Orange Revolution,” Foreign Affairs 84, no. 2 (March –April 2005): 35–52; and Andrew Wilson, Ukraine’s Orange Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006). ↩

- For more on Ruslana and other women in the Maidan, see Marian J. Rubchak, ed., New Imaginaries: Youthful Reinvention of Ukraine’s Cultural Paradigm (New York: Berghahn Books, 2015), 2–4. ↩

- Esherick and Wasserstrom, 845. ↩

- For a first-hand account of this performance and its actors, see Anastasia Bereza, “Imagine people abo jak narodzujutsia symvoly (Imagine people or how the symbols are born),” Ukrains’ka Pravda December 24, 2013, at http://life.pravda.com.ua/person/2013/12/24/146894/, as of March 21, 2015. For an account by the pianist, see Markian Matsekh, “That’s Me in the Picture,” at www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/dec/05/thats-me-in-picture-ukraine-protest-piano-matsekh, as of December 16, 2016. ↩

- Wu Hung defines the Tank Man as “a condensed image” of the event, the one “that stands above the rest and embodies them.” Hung, 84. ↩

- Olexandra Navrotska, Facebook comment to the author, November 19, 2014. Images are at www.facebook.com/hrom.sektor.euromaidan/photos/?tab=album&album_id=638722802833323, as of July 15, 2016. ↩

- See Strike Plakat Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/strikeposter/, as of July 20, 2016. In December 2013, the Ukrainian Museum in New York organized a special exhibition of Strike Plakat’s posters and published a catalogue brochure. See Posters from Euromaidan, December 2013, exh. broch. (New York: Ukrainian Museum, 2013), at www.ukrainianmuseum.org/ex_131213EuroMaidanPostersbrochure.pdf, as of March 21, 2015. ↩

- During his “residencies” in the encampment, the Drohobych-based artist Lev Skop painted dozens of portable icons and distributed them among protesters for free; his painted shield with the image of St. George was even carried through the crowd as in a procession. Lev Skop, Facebook Messenger interview with the author, May 15, 2015. The main icons for the chapel were painted by the Lviv-based artist Ivanka Krypjakevych Dymyd. The extensive use of religious images finds parallels in other occupations that engaged the support of religious groups. For example, revolutionary graffiti featuring verses from the Qur’an appeared on the wall of the American University Library on Muhammad Mahmoud Street in Cairo. See Walls of Freedom, 190. ↩

- Roman Zilinko, telephone interview with the author, November 11, 2014. ↩

- The Crèche project was supported by the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, which provided the artists with a workshop at the Patriarch’s Cathedral of the Resurrection of Christ on the left bank of the Dnieper River in Kyiv. ↩

- Maria Kulykivska, Skype interview with the author, January 23, 2016. ↩

- For video, see Pillars, video 1:17, on Babylon’13 studio’s YouTube channel, at www.youtube.com/watch?v=L0-tqec_jpA, as of January 23, 2016. ↩

- Hung, 109, fig. 19. During recent occupations in the Arab world, images of current dictators became focal points. For instance, the Tunisian revolution used the crossed-out face of then-president Ben Ali juxtaposed with a voodoo doll as one of its principal symbols. See Dounia Georgeon, “Revolutionary Graffiti,” Wasafiri 27, no. 4 (2012): 70. In 2012, after Islamists had gained power in Egypt, the artist El-Teneen, using the style of Shepard Fairey’s Obey Giant campaign, designed a poster featuring the face of the Salafist leader Adbel Moneim El-Shabat and the word “Backwards.” See Walls of Freedom, 182–83. The visual invectives against Viktor Yanukovych, former criminal and then the president of Ukraine, occurred during the Maidan, too. On the Tribunal, an open-air assemblage consisting of the judges’ seats and a cage next to them, the protesters mounted a chained, life-size manikin of Yanukovych dressed in a prisoner robe and sitting on a golden toilet. The last detail referred to the urban myth that Yanukovych had a flush toilet of pure gold installed in his private residence in Mezyhiria near Kyiv. ↩

- Chantal Mouffe, “Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces,” Art and Research: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods 1, no. 2 (Summer 2007): 3, at www.artandresearch.org.uk/v1n2/mouffe.html, as of March 21, 2015. I borrow the term “counterenvironment” from Marshall McLuhan, who defines it as an “indispensable means of becoming aware of the environment in which we live.” McLuhan quoted in Kenneth R. Allan, “Marshall McLuhan and the Counterenviornment: ‘The Medium is the Massage,’” Art Journal 73, no. 4 (Winter 2014): 22–45. ↩

- For example, Gregory Sholette, who witnessed the Maidan’s defensive structures in April 2014, described them as “monuments” and later used parts of them for an exibition in Kyiv. Sholette, “On Maidan and Imaginary Archive Kyiv, Spring 2014,” at www.gregorysholette.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Maidan-and-Imaginary-Archive-Kyiv-text-June-2014LB.pdf, as of March 21, 2015. ↩

- For a detailed study of the Peace Tower and its predecessors, see Francis Frascina, Art, Politics, and Dissent: Aspects of the Art Left in Sixties America (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1999). ↩

- Describing a similar incident when Occupy Wall Street protesters used Mark di Suvero’s sculpture Joie de Vivre in Zuccotti Park, Yates McKee contextualizes it as the “détournement,” the Situationist International’s artistic method focused on inverting capitalist symbols against themselves. McKee, “The Weird Red Thing,” n.p. ↩

- See Antin Mukharskyi, Maidan: Art of the Resistance, video, 45:42, at www.youtube.com/watch?v=JudEEhp4pf4, as of May 7, 2015. ↩

- For details on the Barbican, see Antin Mukharskyi, “Maidan: Mystetstvo sprotyvu (Maidan: the art of resistance),” in Maidan: Revolutsia Dukhu, 233. ↩

- Roti in Chris Cunningham, To the New Ukraine—(Short), video, 5:36, at https://vimeo.com/87383241, as of December 12, 2014. ↩

- Ibid. The choice of Christmas Day for the sculpture’s deposition on the square emphasized its birth symbolism, too. ↩

- Mitchell, 15–16. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Agata Lisiak, “Women in Recent Revolutionary Iconography,” Widok: Teorie i praktyki kultury wizualnej 5 (2014), at http://pismowidok.org/index.php/one/article/view/162/290, as of October 18, 2015. ↩

- Alexandra Parrish claims that Roti had nurtured the idea of a sculpture for several months before the Ukrainian events, and then impulsively decided to contextualize it with the Maidan. See Parrish, “A ‘New Ukraine’ Sculpture in Independence Square by Roti,” Brooklyn Street Art, January 29, 2014, at www.brooklynstreetart.com/theblog/2014/01/29/a-new-ukraine-sculpture-in-independence-square-by-roti, as of March 21, 2015. ↩

- On these laws, see Timothy D. Snyder, “Ukraine: The New Dictatorship,” New York Review of Books, January 18, 2014, at www.nybooks.com/daily/2014/01/18/ukraine-new-dictatorship/?insrc=wbll, as of December 29, 2016. ↩

- See Claudia Mesch, Art and Politics: A Small History of Art for Social Change since 1945 (London: I. B. Tauris, 2014), 96–97. ↩

- Jerzy Konopie, Facebook Messenger interview with author, December 18, 2014. A few days after the demolition of his artwork, the artist created another version at the foot of Instytutska Street. This time, however, in the fashion of Joseph Kosuth’s installations, Konopie supplemented his artwork with an explanatory text. Eventually, he relocated his Targets to the Artistic Barbican, where the work survived until the end of the occupation. ↩

- Lucy R. Lippard, “Trojan Horses: Activist Art and Power,” in Art after Modernism, ed. Brian Wallis (New York: New Museum, 1984), 341. ↩

- Police destroyed the catapult around midnight on January 21, 2014. Another model, built of metal, was brought to Hrushevsky Street on February 21, 2014. This was redeployed to the garden at the National Art Museum of Ukraine. ↩

- Andrij Meakovskyi, Facebook page, February 2, 2014, at www.facebook.com/meako689/posts/643106935743144, as of March 21, 2015. ↩

- Andriy Zelinskyi, Facebook Messenger interview with an author, November 17, 2014. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Amy Mullin, “Feminist Art and the Political Imagination,” Hypatia 18, no. 4 (Fall–Winter 2003): 191. ↩

- Ibid., 197 and 209. ↩

- For Nefertiti, see Walls of Freedom, 213. On irony in street art and in Banksy’s interventions, see particularly James Brassett, “British Irony, Global Justice: A Pragmatic Reading of Chris Brown, Banksy and Ricky Gervais,” Review of International Studies 35, no. 1 (January 2009): 219–45. ↩

- In one of his interviews, #Sociopath revealed Banksy’s role as a “trigger” that inspired him to start painting on the streets. He recalls that after seeing Banksy’s documentary Exit through the Gift Shop, he got “a crystal-clear feeling” that he knew “how to paint.” Yaryna Vynnytska, “Ukrainian Banksy: Street Artist #Sociopath Talks about Social Art,” Ukrainian Week 9 (June 2014): 46–47, at http://ukrainianweek.com/Culture/115470, as of April 8, 2015. ↩

- Ellen Handler Spitz, “An Insubstantial Pageant Faded: A Psychoanalytic Epitaph for New York City Subway Car Graffiti,” in Postmodern Perspectives: Issues in Contemporary Art, ed. Howard Risatti, 2nd ed. (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1997), 230. ↩

- #Sociopath, e-mail interview with the author, December 5, 2014. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- The artist quoted lines from Shevchenko’s poem “Hamalia” (1842, first pub. 1844), Lesia Ukrainka’s play Autumn Tale (1905, first pub. 1929), and Ivan Franko’s tale “Mykyta the Fox” (pub. 1890). My thanks to Tetiana Pavliv for the help with the translation of Shevchenko. ↩

- Olexander Bryndikov’s Facebook page, November 13, 2014, at >www.facebook.com/camrade.briundik/posts/1509157089355897, as of March 21, 2015. ↩

- Theodeore Synkellos quoted in English translation in Bissera Pentcheva, “The Supernatural Protector of Constantinople: The Virgin and Her Icons in the Tradition of the Avar Siege,” Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 26 (2002): 9–10. ↩

- There is a parallel in the Tiananmen story of the Goddess of Democracy, a thirty-three-foot statue representing a Chinese woman holding a burning torch. As Hung explains, after protesters built it on the square opposite the giant portrait of Mao, they perceived it as an inherent part of themselves, as one that stands for them. Even when tanks invaded the square, people remained with the statue, some dying next to it. Hung, 111–13. ↩

- The shields were included into the exhibition “I Am a Drop in the Ocean: Art of the Ukrainian Revoluation,” at the Künstlerhaus in Vienna; see http://www.k-haus.at/de/ausstellung/229/i-am-a-drop-in-the-ocean.html, as of August 20, 2015. The show traveled to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Krakow; see https://en.mocak.pl/i-am-a-drop-in-the-ocean-art-of-the-ukrainian-revolution, as of August 20, 2015. ↩

- Kateryna Chueva, Facebook Messenger interview with the author, June 16, 2016. Thanks to Ihor Poshyvailo, the leader of the Maidan Museum group, for providing the dimensions of these artworks. ↩

- On site-specificity in general, see Miwon Kwon, “One Place after Another: Notes on Site Specificity,” October 80 (Spring 1997): 85–110. On the site-specificity of street art, see Nicholas Alden Riggle, “Street Art: The Transfiguration of the Commonplaces,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68, no. 3 (2010): 243–57. ↩

- An article by Michael North suggested to me contrasting the related concepts of “social sculpture” and “human ornament”: North, “The Public as Sculpture: From Heavenly City to Mass Ornament,” Critical Inquiry 16, no. 4 (Summer 1990): 865–68. Mitchell cites the article in his discussion of the space of occupation: Mitchell, 24–25. On Beuys’s thinking, see Eric Michaud, “The Ends of Art according to Beuys,” trans. Rosalind Krauss, October 45 (Summer 1988): 37–46. The relation of Beuys’s “social sculpture” to occupation was also discussed at Documenta 13 in Kassel and the Berlin Biennale 7 in 2012, where art activists mounted installations imitating the OWS encampment. Sebastian Loewe, who examined both cases, argues that after an occupation enters the context of the art world, it loses its political significance and becomes “subject to aesthetic pleasure,” while people involved act as “spectators” rather than “politically engaged participants.” Loewe, “When Protest Becomes Art: The Contradictory Transformations of the Occupy Movement at Documenta 13 and Berlin Biennale 7,” Field 1 (Spring 2015): 198. ↩