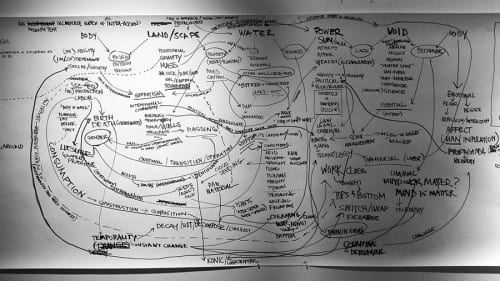

A.K. Burns and I encountered each other’s work during our time at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University during the 2016/2017 academic year. At the time, A.K. was working on her five-part film cycle Negative Space; the second episode, Living Room, opened at the New Museum in New York in January 2017. Meanwhile, she was working frenetically on two other solo shows. Her spacious studio became a retreat for me as I worked on a book manuscript, and I began to think of the different zones within that space as comprising different components of her equally sprawling practice. On one wall, a constellation of terms mapped out on butcher paper diagrammed the complex conceptual structure of her ongoing, multi-year project. On the opposite wall, a whiteboard of phrases pulled from campaign slogans and postcolonial philosophy were composed and recomposed into a word collage. At her desk were two monitors for editing video and sound, and where she reached out to friends for a score, a dance, or an improvised conversation. The floor and workbenches were zones of messy material exploration. A.K. works across these different registers—the material and formal, the linguistic, the explicitly political, the practical—to produce a symbolic language that is both idiosyncratic and highly referential. This tendency is particularly pronounced in her ambitious piece, Negative Space. Organized around such broad conceptual prompts as the sun (A Smeary Spot, 2015), the body (Living Room, 2017), water, land and the void, each episode in Negative Space plays out allegorical considerations of the nature of reality and the binaries that we use to structure that reality in inequitable ways.

In this annotated commentary, A.K. and I discuss the first episode of Negative Space titled A Smeary Spot, a fifty-three-minute, four-channel video installation that premiered in September 2015 at Participant Inc. in New York. We walk through selections from the script, which A.K. constructed out of appropriated and altered excerpts from poetry, philosophy, and fiction. Feminist sci-fi by writers like Joanna Russ, Ursula K. Le Guin, and the new materialist philosophy of Karen Barad were starting points for Negative Space though its cultural touchstones are far more wide-ranging. The script circulates as a poster for the installation, and the excerpts that appear below are details of that poster. In keeping with the collaborative methods that A.K. has developed in her previous projects, we have structured this piece as a kind of mutual annotation. My responses to the video installation appear in the column on the left, while A.K.’s responses to my comments appear in the column on the right. They are addressed both to one another and to the reader.

This first episode of Negative Space acts as an entry point into the constellation of ideas and images that comprise the entire film cycle; the character Mother Flawless, a “clairvoyant psyche,” is, for me, the linchpin of this episode. Our conversation will begin with her, and will follow with a consideration of her relationship to other characters (or “acting agents” as A.K. refers to them). Mother Flawless is, of course, played by the late Flawless Sabrina, the iconic drag performer and activist who took on the moniker “Mother” in the 1950s. I’ll speak more to this below, but for now it strikes me that Flawless’s character is a kind of citation of herself, and that citation is a recurring device of the film. Flawless’s clairvoyance, for example, recalls her real-world talent for reading tarot cards.

The allusive quality of the film resists quick summation; with each new interpretive layer, its reference points multiply, compounded by the viewer’s own associations, spreading out rather than drawing in. Per Judith Butler, these reinscriptions could be read as acts of agency—citation being a prerequisite for performing identity in the first place1. But I want to draw out the etymological meaning of “citation,” as an act of summoning or calling forth. The re-citations composing A Smeary Spot serve as reminders that one can opt out of existing citational structures that reinforce dominant discourses, voices, and points of view, and opt in to citational structures that call forth and amplify a community, that summon it into existence from moment to moment2.

–Melissa Ragain

[one_half padding=”0 15px 0 0″]

Melissa Ragain: An orienting figure like Mother Flawless is necessary, because it’s easy to get lost in the weighty philosophical dreamwork of A Smeary Spot, even before the dialogue begins. At the start of the film’s looped sequence, Matana Roberts performs the “OOO Sax Solo” in a black-box theater bathed in blue and red light. The tune has a hypnotic effect that eases the viewer into and out of the world you craft for them, and prepares the way for Mother Flawless’s monologue in the next scene.

I’m curious about the nod to object-oriented ontology (OOO) in the title of Roberts’s song. “OOO” was coined by Graham Harman as philosophical shorthand for the significant move away from philosophies centered on the human toward objects as sources of meaning3. Meanwhile, the physicist and philosopher Karen Barad, who plays a major role in your own thinking about materiality, questions the metaphysical presumption of the object altogether, instead making the case for the ontological priority of phenomena over objects. She also argues for the concepts of entanglement and intra-relation, as opposed to the interrelations of objects. Barad offers us difference, differentiation, differential speeds and intensities—viscosities and assemblages that are responsible for how “matter comes to matter.”4 Barad’s innovative use of terms like intra-action signals a new materialism that is indebted to feminist theory, and that insists that matter is not the ground upon which politics plays out, but that the political is thoroughly imbricated within the material.

The sax solo, or at least its title, sets up the theoretical interests of the film we’re about to see, where philosophy acts as a spur to images and in which images perform philosophically. I tend to hear the improvisational nature of the solo itself, the sense that it is unspooling out of the author rather than proceeding along as series of logically predetermined steps, as a read on how new materialism works differently than other forms of philosophy, and maybe why it’s appealing to feminists, being less bound by conventions of academic language (like what I just resorted to in the previous paragraph) and more open to metaphor and poetic image as sources of knowledge.

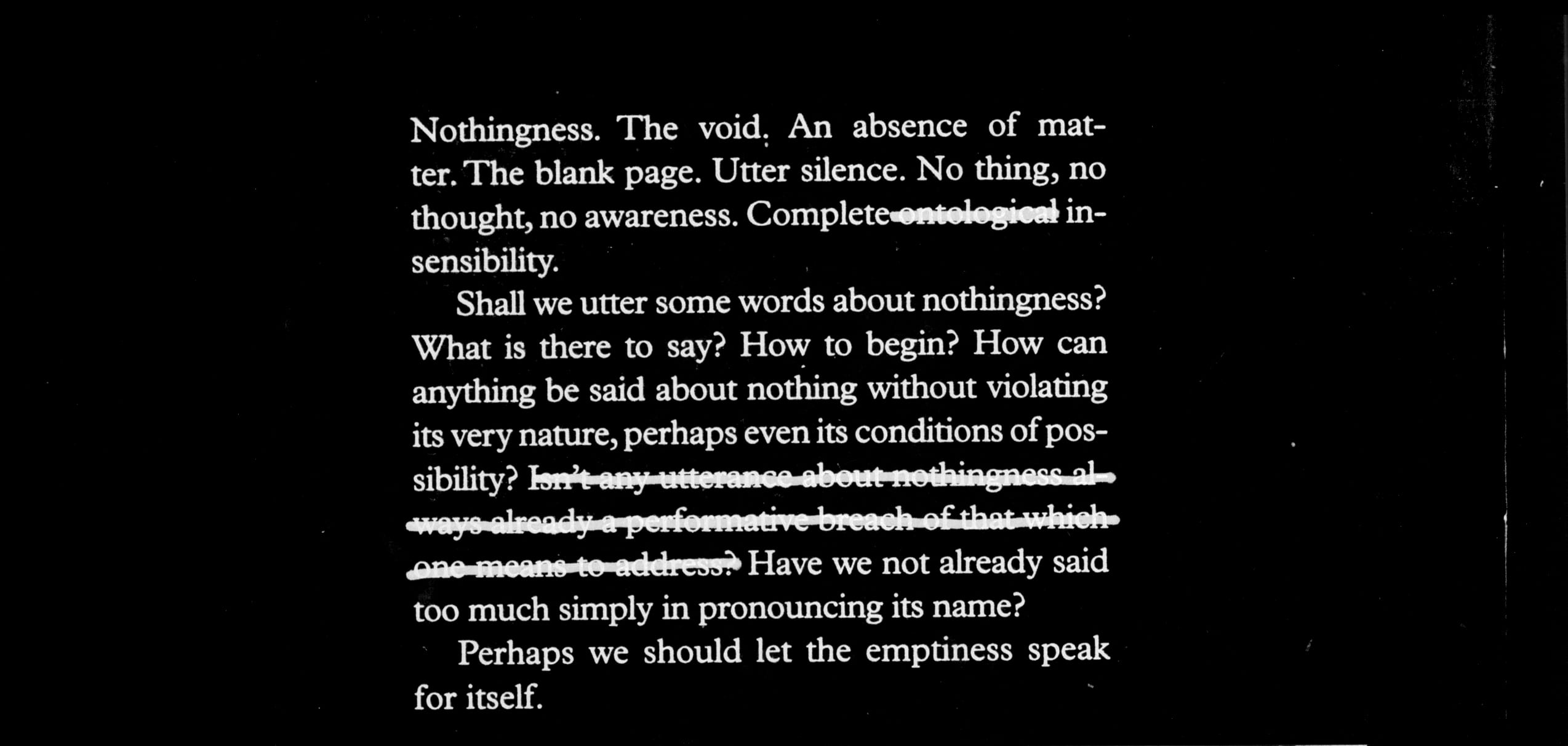

Mother Flawless—a woman in her late 70s with long blond hair, glasses, a modest turtleneck, and a collection of statement rings—appears at the end of Roberts’s solo to deliver her opening monologue (above). She is our charming Virgil through the not-so-empty emptiness that follows in the subsequent scenes. Her opening address is taken from Barad. Barad’s consideration of nothingness is especially important here, as it undermines the long-held idea that the void plays a subordinate role to the thing or object of consideration in theories of consciousness.

In visual art, the void has as its corresponding concept the notion of the ground, the formless substance-like area behind the figure—negative space as your title indicates—a space that cannot, according to everyone from Immanuel Kant to Edgar Rubin to Sigmund Freud, invoke the beautiful. A perceptual psychologist, Rubin was especially concerned about the ground’s capacity to be perceived as a figure, describing the background of the Sistine Madonna as a monstrous lobster assaulting the painting’s rightful figures. Following their line of thinking, the ground/void/formless is incapable of capturing our attention, implanting itself in our memory, or generating any affective response beyond that of disgust, horror, and a sense of impending danger. The only appropriate position for nothingness is for it to recede, and to subordinate itself to the compelling nature of the figure/thing/form. Kant got around this problem by shifting our attention away from the void, which he recast in terms of the sublime, toward our own reasoned capacity to conceive of it. But for Barad, and for you, it’s the demand for subordination itself that’s under revision—the subordination of void to form, of matter to concept, or of action to representation.

In the quotation above, you revise Barad’s words, deleting their direct reference to ontology and performativity, pulling Mother Flawless’s speech out of academic discourse. Without these philosophical flags, Flawless sounds oracular. In the tradition of prophetic language, her speech is expository but not explanatory. Not only does she get to pull the curtain back on this new world of the void in the coming scenes, but it’s clear that she has an exceptional position within the film’s pantheon.5 A Smeary Spot strives toward the status of an origin story with Flawless a central point of origin, a mother perhaps in the enzymatic sense, as in cider vinegar made with the “mother.”

The character of Sabrina-as-Mother is a nod to the actor’s real life role as a transgender activist and mentor, as well as to Barad’s valorization of the void as a generative state of “radical openness,” a space of “infinite possibilities.”6 “[I]t may” she writes, “in fact be the source of all that is, a womb that births existence.” She does seem to enjoy a position of benevolent authority compared with the film’s other characters, as she amuses herself with thought experiments meant to induce Copernican revolutions in consciousness.

[/one_half]

[one_half padding=”0 0 0 15px”]

A.K. Burns: Opening with the triple exhale, Ohh Ohh Ohh, the sax solo is an exercise in breathing and therefore life and being. Air circulates through the body, through the saxophone and is visualized through the colored fog. The (OOO) abbreviation was an onamonapiac wordplay prompting a shift in perception for how we might enter this cosmology. That said, I actually think OOO is philosophically bogus. Object-oriented ontology assumes a sameness of all things, a bland pancake world where discord could be undone in an indistinguishable soup of atomic particles. Rather, the thing I am most interested in exploring through this work is difference: a belief in the liveliness, temporality, and inevitable difference of all matter. This is where (quoting) Barad enters the picture as well as the notated multiplicity of each performer and the improvisation— a flux of sound determined by the fluidity of felt sensibilities. I use OOO mostly as a humorous nod towards new materialist discourse.

The scene begins with the OOO Sax Solo by Matana Roberts followed by Mother Flawless reciting an excerpt from a text by Karen Barad. A.K. Burns, three-channel video excerpt from A Smeary Spot, 2015, HD color video (artwork © A.K. Burns, excerpt provided by the artist, Callicoon Fine Arts, NY, and Michel Rein Gallery, Paris/Brussels)

As for “Mother Flawless,” is she our Virgil or is she our Thespis? She’s not so much the creator of these poems but rather the medium through which transmission and translation occurs. This is the theater after all—so exposed in this sequence—a site of perpetual construction and mimicry. Her embodiment here is drag (more than transgender). Being is a performance. Jack (Doroshow) performed Flawless Sabrina as much as she lived her. And in this work she is a variation on herself. Mother Flawless uses ritualized drag as an ontological condition of playful indeterminacy. Her status as such in the video is closely related to who she was in her life-time (Jack Doroshow passed on recently, on November 17, 2017). I had planned to return to Flawless to read tarot (cards I pulled for each of the episode subjects: void, body, power, land and water) in a future episode. While Flawless Sabrina was developed as her performance persona, you might also just see Jack out at Julius’ Bar in the village and they were always beautiful. A collage of gender and era and esthetic signifiers that were so exquisitely composed that it was never clear if she was trans or in drag or both or neither. She never cared which name you used or gender. Honestly when you look that fabulous, who really gives a damn? This is a position I personally feel deeply aligned with. I have no real interest in policing how people name me or gender me. Flamboyancy has long been the tool of choice for queer and marginalized bodies. I deflect and enchant your determining gaze by “workin it”—with a swish and a snap!

Oh, and Last but not least, a note on the philosophical patriarchy and their notion that there could be nothing “beautiful” (which I would argue is a coded way of saying nothing “useful”) about nothing. Or that nothing would need to be aligned with the ejaculatory grandeur of the sublime to have any value as a subject—or should I say, non-subject. Nothingness is negated, or marked as a lack in the philosophical traditions because it is the unnamable and unknowable that terrorizes knowledge production and therefore the ability to capitalize. Nothing—the terrorist—is a rupture in mechanisms of power, a celebration of ecstatic unproductive possibilities. Much like a good outfit.

[/one_half]

[one_half padding=”0 15px 0 0″]

Melissa Ragain: Despite the film’s debt to science fiction, you have also embraced Margaret Atwood’s notion of speculative fiction as something that, in contrast to scientistic fantasy, “could really happen.”7 Indeed, the notion of a speculative present is central to the kind of seer we understand Mother Flawless to be. The Sybilline figure passed down to us from antiquity and esoteric Christian theology was burdened by the fore-knowledge of inescapable catastrophes, whereas Mother Flawless speaks gently of things as we might want them to be, now. In the above clip, Flawless advises us to simply, “let the nothingness speak for itself”—a way of handling things in the present not as catastrophic, but as welcome developments with things to tell us.

Mother Flawless exists within one version of the void, the black box theater, a protected modular space for imagination and prescient sight. Flawless’s monologue leads the viewer out of the darkened black box theater, to the film’s next location, the desert terrain near Lake Powell in Southern Utah. Both spaces—the stage and the desert—host a group of protagonists known collectively as the “Free Radicals.” Like electron-seeking molecules from which they take their name, the Free Radicals are catalytic agents within the landscapes of the film. Where Mother Flawless prognosticates, the Free Radicals negotiate the material facts of their landscape largely through their actions. A free-roving chorus, when they do speak the Free Radicals’ dialogue is descriptive more than predictive; they articulate a phenomenology of the void, and speak to the politically ambiguous nature of the marginal spaces that they occupy.

The scenes in Utah were filmed on public land. American public lands are located primarily in the West. Most of it entered the public trust because it was remote or otherwise unprofitable. Taken out of economic circulation, and geographically isolated, these common spaces have become sites for experiments in contemporary nomadism. Two Free Radicals, played by the dancers niv Acosta and Jen Rosenblit, enact this transitional state. Clad in Mylar blankets and eccentric hiking clothes that offer little protection against the elements, they are in constant motion as they seek out life-sustaining water, shade, and air. The sound of the wind is cut by the interrupted broadcast of an AM radio station; we hear that someone plans to “stay and take their chances” as the first drops of a rainstorm hit the dusty ground. The scenes of the Free Radicals are accompanied by long-distance shots of the Ob-surveyor (performed by Katherine Hubbard), a character who documents and measures the landscape. A collapsing of scale occurs when her long-distance shots are paired with close-ups of beetles and ants in the film’s foreground. Life in the emptiness is inconspicuous but sturdy, full of ad hoc solutions and alien forms generated in response to desiccated, inhospitable conditions.

It seems to me that the Free Radicals personify this rugged life on both sides of the void, whether rambling through the desert with jerry-rigged camping gear, or producing linguistic bricolage on stage. In one scene, back in the black-box theater, a Free Radical played by Simon (Grace) Dunham emerges from pile of rubbish. In contrast to the subtle and intricate systems at work the desert, only fragments persist within the wasteland of the staged void, whether as material detritus or bits of language. It’s from these pieces that the Free Radicals cobble together new rituals and reconfigure philosophical and narrative language into a common lyric voice.

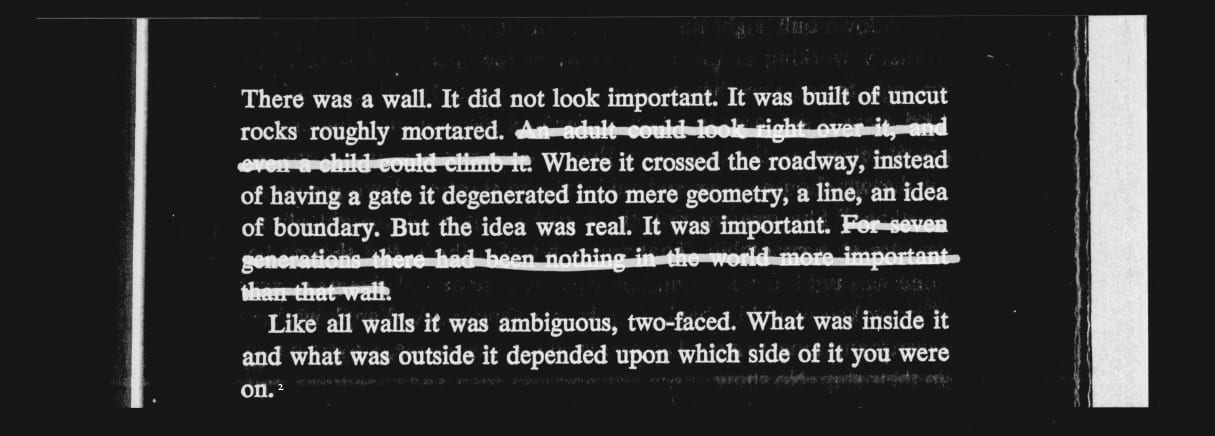

Dunham’s short monologue is taken from the opening lines of Ursula K. Le Guin’s sci-fi novel The Dispossessed (1974). The original excerpt describes a wall that surrounds a space-port on a planet, which, as the subtitle of her novel, An Ambiguous Utopia, suggests, is either a free and independent society or the colonial subject of its adjacent twin planet, depending on one’s perspective. In Le Guin’s narrative, the wall represents simultaneous states of freedom and unfreedom, “an idea of a boundary,”8 that is nevertheless real and consequential for those forced into a relation with it. After dressing in the gender-neutral Free Radical uniform of a black t-shirt, jeans, and belt, Dunham speaks Le Guin’s lines while carefully applying red lipstick. It is not a leap to apply Le Guin’s metaphor of the wall to the problems of gender construction, though I am curious if the rigidity of her wall metaphor reframes it as a hurtle to thinking of an alternative performativity. Le Guin was writing in the midst feminist essentialism, and her refusal to idealize the more conventionally feminine attributes of the utopian colony of Anarres suggests her discomfort with the simplistic binary values of second-wave feminism. Your script elides the wall’s history and material specificity, reinforcing its role as a metaphor for the individual’s failure to escape culturally enforced patterns of thought, patterns that have traditionally been sci-fi’s role to question.

[/one_half]

[one_half padding=”0 0px 0 15px”]

A.K. Burns: Time is non-linear in A Smeary Spot. It is a loop, and in the installation, the three primary channels run continuously while the credits roll on a separate monitor. Therefore, performers, their gestures, and the language they deliver simply usher us from one instance or site to another (between mental and physical planes) rather than following a logic of a before and after, cause and effect, or a linear narrative arc.

Part of the way the “present” is represented is through the interwoven radio broadcasts. Most of the recordings are from NPR during Hurricane Sandy. I was working on the first edits for the video while Sandy was blazing outside my apartment, so it’s a combination of emergency warnings and news about the Supreme Court and refugee crisis. The following episode (in the Negative Space pentalogy), Living Room, also draws from the current political climate through the abstraction of the 2016 United States presidential campaign slogans used in the dance sequence.

In the scene where insects and the Ob-surveyor are shown side by side in the desert landscape, scale collapses. Scale is always relative, dependent on your distance from the thing observed. This is a formal principle that runs throughout the film and is exploited through the use of micro/macro framing. The screens used in the installation are about seven by twelve feet each so the viewer feels embedded in the landscape/theater. Through this effect, scale shifts can make the performers bodies not only appear but also feel ant-like or monumental in relation to the viewers own body.

As for this scene with the Free Radical, situated back in the theater, wearing what I like to call “activist drag”—black t-shirt, jeans, and combat boots—Simon Dunham recites Le Guin while applying lipstick in the mirror. On another screen the Ob-surveyor makes impermanent marks with architectural snap line on the surface of dusty desert rocks while measuring the site with her body. Through the double vision of the mirrors reflection, lining lips with the bright red lipstick and in the simultaneous world of the Ob-surveyor, Le Guin’s text underscores the line, the wall, and the various methods of marking as ambivalent, rather than defining. Much like the use of scale, here it’s your place, your position, and your perspective that determine what is and isn’t. The three primary screens (built as freestanding walls) in the installation are lined up horizontally to cut across and cut up the exhibition space in such a way that it appears both as sprawling landscape-oriented portal for the lush visuals and a literal wall.

Simon (Grace) Dunham, a Free Radical, applies lipstick while reciting an excerpt from Ursula K. Le Guins’s The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia. A.K. Burns, single channel video excerpt from A Smeary Spot, 2015, HD color video (artwork © A.K. Burns; excerpt provided by the artist, Callicoon Fine Arts, NY and Michel Rein Gallery, Paris/Brussels)

[/one_half]

[one_half padding=”0 15px 0 0px”]

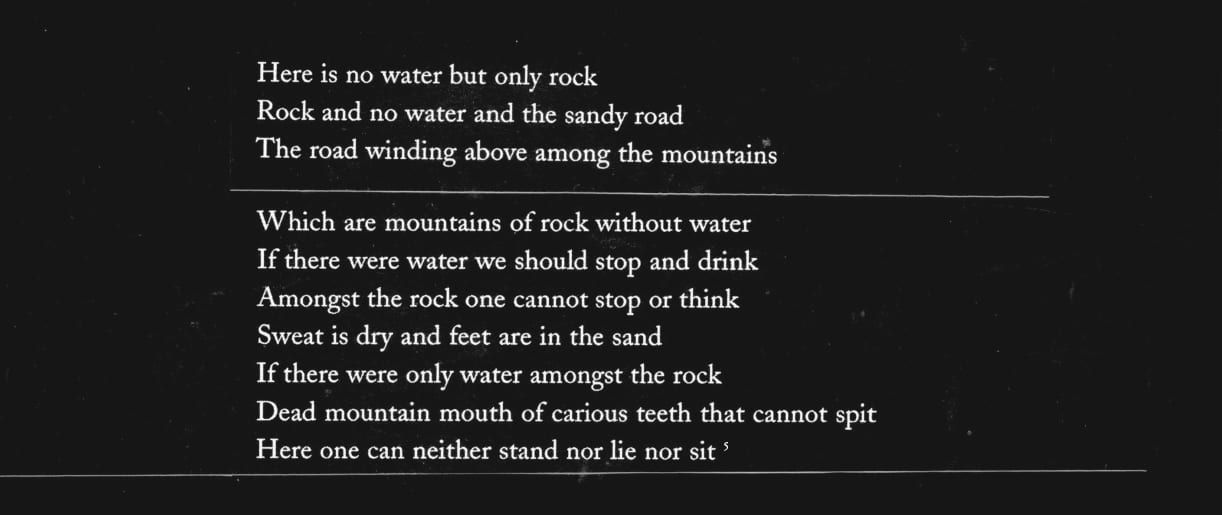

Melissa Ragain: Here in the mental no-space of the stage, the Free Radicals play out the unfixity of the subject’s relation, not only to dominant categories, but also to division itself. Of the open possibilities of the concept of negative space offers, the denial of the boundary itself is one of the most potentially radical, and certainly one of the anxieties attached to negative space since the articulation of the figure-field distinction in 1919. The Free Radicals perform numerous acts of merger or enfolding of matter into the body. They consume pressed juice; they use their bodies to “play” a table as though it were a theremin. In the clip above, one Free Radical (played by Jen Rosenblit) applies enough mud to her face that it takes on the appearance of a sculptural relief. As she does so, she recites lines from T. S. Eliot’s epic poem The Waste Land (1922).

Taken from the final section of Eliot’s poem, “What the Thunder Said,” Rosenblit’s monologue is, on the surface, a song about a desert, a space beyond the chaos of the everyday, and therefore a kind of transcendent landscape. But it is also a space devoid of beauty, organic life, or rest. The dry land in Eliot’s poem represents his critique of the desire to transcend mortality; even his own Sybilline figure, Madame Sosostris, couldn’t overcome her cold. The fifth part of The Waste Land also promises redemption, the return of divine speech, and the regenerative powers of rain and water that appears to return in the final desert dance sequences of A Smeary Spot.

Like the quotes from Barad and Le Guin, Eliot’s poem is a textual source, but it also serves a structural precedent for A Smeary Spot. The film’s five-part arrangement, its focus on emptiness and fragmentation, its use of appropriated texts, and its polyvocal narration, all recall Eliot’s poem. The clairvoyant Mother Flawless is a latter-day Sosostris. Even Eliot’s ritual understanding of life and death seem echoed by the staged actions of the Free Radicals. And yet, Eliot’s poem is driven by a tragic spiritual economy of vulgarity and transcendence, fall and redemption, and marked by his insistence on the spiritual shortcomings of mankind. The Free Radicals conduct their existence among the same pentacle of earth, air, fire, water, and spirit that Eliot’s characters do, but they do so without his tragic religious anxieties. Think of Eliot’s countervailing forces of lust versus spiritualizing fire, or of sexual violence versus self-control and sacrifice. Where the five-part structure of The Waste Land recalls the structure of Elizabethan tragedy, in A Smeary Spot it serves to distribute the viewer’s attention, much the way that the Free Radicals serve as a decentralized protagonist. Their actions serve as agitations in both the chemical and political senses of the term, driving the narrative in many directions at once.

The film’s indebtedness to Eliot draws out your significant distance from him. A Smeary Spot is haunted neither by Eliot’s longing for transcendence nor his desire to recoil from the world. Where the rain and thunder in Eliot’s final section have been read as emblems of the divine redemption of flawed humanity, Rosenblit’s performance of Eliot’s lines maintains the material facticity of both its dust and its water. Dust and water make mud after all, and mud has certain material capacities and limitations for form-building, capacities that Rosenblit explores in relation to her own body. In another scene, she recites a modified quotation from Karen Barad: “I am not an outside observer of the world. Nor am I located at particular places in the world; rather I am part of the world”9 —all while drinking pressed juice, a similarly literal, if more banal, act of folding matter into oneself.

In his review of James Joyce’s epic novel Ulysses, Eliot famously dubbed the book an example of the “mythical method,” for its fusion of the classical and the modern that lent order to the “immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history.”10 I won’t embarrass myself by giving your method a cute name. If A Smeary Spot shares the epic and allusive qualities of Eliot’s “method,” its classicism, if I can call it that, hardly shares in his elegiac longing for an Apollonian past. In place of his “futility and anarchy,” A Smeary Spot generates its own panorama of agency and embodiment grounded in the contemporary sexual and political imagination. Perhaps it is the allowance of imagination that makes A Smeary Spot an appropriately contemporary myth.

[/one_half]

[one_half padding=”0 0px 0 15px”]

A.K. Burns: Oh, we should totally come up with a cute name for my method! It’s true that Eliot is a moralizing force in his work, and that is ultimately counter, or too authoritarian a narrative for the world of A Smeary Spot because short-comings or failure are essential to participating fully in this world—after all, it is deeply human to be flawed.

I extract small parts of texts in an effort to de- and re-contextualize them. I’m always interested in how flexible language can be, especially because it is a medium bound up in literal meaning. I’m also interested in the baggage of what was (the quote, reference or as noted above, citation), and how that carries forward in mutation, informing rather than forming its meaning. I was compelled by this excerpt as an eloquent description of the desert, of the inhospitable coarseness of that landscape. The human body, 60% water, is so dependent. The challenge in merely existing (ie. “neither stand nor lie nor sit” 11) is exaggerated by the deserts lack of liquids.

This was one of the last scenes I shot. It was at a stage when I was aware I needed to construct specific images that could visually bridge the site of the theater and the site of the desert. I was thinking about the binary of rock and water, which led me to think of what happens when you mix the two: as you point out, mud. This prompted me to think about what one does with mud, and the luxury body-care activity of applying a mud mask. In this case, the body care becomes body excess as Jen Rosenblit (a Free Radical) continues to apply the mud well beyond necessity. While the text describes the most basic ontological survival and materiality, we are seduced by the gestures of this amplified ritual. Her face—shot close-up, again shifting the scale from figurative to monumental—transforms into a mountainous terrain. Rosenblit is manifesting, in a sculptural sense, the thinness of the lines between inanimate and animate. Or as you quote “I am part of the world,” rather than being in a particular place, she is the place.

The scene begins with Free Radicals cleaning off a table they were gathered around that becomes a touch pad operated by performer Jen Rosenblit. On the left screen, Rosenblit applies a mud mask in excess while reciting an excerpt from T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. A.K. Burns, three-channel video excerpt from A Smeary Spot, 2015, HD color video (artwork © A.K. Burns; excerpt provided by the artist, Callicoon Fine Arts, NY and Michel Rein Gallery, Paris/Brussels)

[/one_half]

![A.K. Burns, detail of poster for A Smeary Spot, 2015 (artwork © A.K. Burns). Source quotation: Guy Hocquenghem, The Screwball Asses [1973] (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), 34.](http://artjournal.collegeart.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/SmearySpot_script_sect_4.jpg)

[one_half padding=”0 15px 0 0px”]

Melissa Ragain: Shape-shifters are ubiquitous in folklore and fantasy, since they speak to a popular desire for metamorphosis, typically between human and nonhuman forms. The Shape-Shifter appears in many guises throughout the film, as Aunt Be/e, as Manet’s Olympia reclining on a pile of air mattresses, and as “becoming,” a character in a state of perpetual preparation at their toilette. In the film’s final scene one of its mythic figures, the Shape-Shifter, gives permission to indulge a utopian fantasy. The text that “becoming” recites is from Guy Hocquenghem’s 1973 critique of capitalism as a phallocentric distortion of homosexual desire. Hocquenghem’s “mythical third sex” demanded a return to a pre-symbolic, polymorphous sexuality, an identity prior to object choice, and gender formation.12 In the guise of Olympia, the Shape-Shifter opines to live “without the terror of the phallus” to make way in this final scene for an unalienated “relation of weaknesses.” After speaking Hocquenghem’s words, with extreme care, “becoming” affixes a name-plate to an army dress uniform: “MANNING.”

Unlike their folkloric predecessor, this Shape-Shifter resides in a state prior to transformation, prior to crossing or even constituting the boundary that for Dunham’s Free Radical remained a very “real” idea. And yet at the opposite end of the story from Mother Flawless, “becoming” appears as a fulfillment of the promise of the void reimagined as the state of non-determination. Mythical though they are, the nomadic agents, psychic intelligences, and shape-shifting shamans that populate A Smeary Spot are nevertheless bodies subject to historical forces; in 2015, when it premiered, Chelsea Manning was still in prison with no pardon in sight. It is not, as Eliot might have it, that these figures fail to transcend history, but that they exist quite self-consciously within it, if at its margins.

[/one_half]

[one_half padding=”0 0px 0 15px”]

A.K. Burns: I’m interested in your repeated reference to my reference to the Shape-Shifter as “becoming,” blatantly exploiting the verb-ness of her constitutive being. Even in her “natural” state she is in a state of getting ready, in front of the mirror and sporting a bathrobe with a towel wrapped head, as if she just stepped out of the shower not yet made-up for public appearance. She is, as you point out, a malleable, unfixed, and active presence—not really identifiable as a proper noun. She in many ways exemplifies Butler’s concepts of (gender) performance, as in, the mere act of being in the world, is just that, an act.

One thing to note is that she mimics but never actually becomes the “other” in a totalizing and indistinguishable way, typical to most shape-shifters. Typically a shape-shifter’s power is in their ability to completely transform with no evidence of their “self” and thereby confound, deceive, manipulate, and undo the actions of the being they are portraying. But this shape-shifter is more like a meme. There is an interpretive quality to her “becoming.” For example, in the restaging of Manet’s Olympia, she lounges on air mattresses (myriad outdoor equipment shows up throughout the Negative Space cycle as a nod to provisional living and how we commodify our relationship to nature) and rather than posing nude, she is wearing a theatrical undergarment for reshaping the body.

Both the texts that are delivered by the Shape-Shifter are quoted from Guy Hocquenghem’s The Screwball Asses. This is a text I have loved for many years, and found its way into this work as the only direct reference to the queer body. I think The Screwball Asses still resonates as a radical text, originally published in 1973 as a critique of patriarchal threads in homosexual masculinity. The work asks for embodied relation of desires that exceeds category. I built this scene around the Shape-Shifter at the vanity mirror, where she recites the above text. In this quasi-bedroom space hangs Chelsea Manning’s jacket in a garment bag. She cares for and fetishistically caresses it. The Manning jacket came out of an interest in various ways I could represent water. This lead me to thinking about leaks being an significant aspect of how water resists controlled. Manning is dually leaky, through information leaks and what I call the “leaky body,” aka the trans body. As noted above, water or fluidity is a central theme, as is containment (like the dammed river in the desert). As I was working through this binary of fluidity and containment, leaks became a fertile place to build from. They speak to the impossibility of totally containing a force (and resource) like water, or gender.

[/one_half]

![A.K. Burns, detail of poster for , 2015 (artwork © A.K. Burns). Source quotation: Joanna Russ, We Who Are About To... (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, [1976] 2005), 1.](http://artjournal.collegeart.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/SmearySpot_script_sect_5.jpg)

[one_half padding=”0 15px 0 0px”]

Melissa Ragain: When Flawless returns later in the film, rolling around playfully in her wheeled office chair, flanked by a water cooler and mini-blinds, she explains to us the tricky nature of space travel like a piece of departmental gossip. Space travel is, as she describes it, like the imperfect folding of a sheet of paper—an inexact science marked by uncertainty and risk. She describes the sun seen from outside our own earthbound reference point (above). Both of her monologues, like Albert Einstein’s famous question to Niels Bohr about a tree falling in the woods, center on the role of observation foiled by a decentered perspective, or by total inaccessibility to the senses. Bohr’s retort to Einstein that the tree cannot make a sound because sound is the act of sensing sonic vibrations is flipped again by Flawless, who registers the void – an area of “Complete span style=”text-decoration: strikethrough;”>ontological insensibility”—as having its own kind of consciousness, despite its insensibility to ours.

A consciousness that can’t be sensed is a ghost.

What can’t be felt through the senses can be felt through the extrasensory abilities of our clairvoyant psyche. Flawless is the chief speculator in this speculative fiction. But to speculate is to run the risk of loss. As you have said, this work “sits near the intersection of speculative fiction and speculative realism.”13 To live in a speculative mode one must move forward on very little information, and stake one’s future on complete conjecture. Flawless makes it look fun. The acceptance of chance, risk, and failure are, after all, necessary for living speculatively because they make space for the faculties of intuition and, importantly, desire.

[/one_half]

[one_half padding=”0 0px 0 15px”]

A.K. Burns: Speculation is about risk but, moreover, about the hypothetical: a method for proposals, inquiries, experiments, and abstraction. My vision for an alternate future is created through this space, of what I call the “speculative present,” in which we perceive, create, perform, and are completely different. The present is an ongoing, ever-shifting instant in which both past and future occur simultaneously. The past gets bogged down with nostalgia and amnesia, while the future tends to be a fantastical realm of ambitions and disappointments. The present is the continuity that keeps us moving, from and to. It is the place of change and action yet to be solidified by various forms of fiction.

In A Smeary Spot, the here and now are abstracted through the ambiguity of non-specific sites and stages. Within this Flawless is a psychic presence. It’s not that she sees things that are in the past or future or spiritual plane, rather she sees the present through a kind of Baradian lens in which indeterminacy and the intra-active liveliness of the atomic world is a map for rethinking the confines of everything from knowledge production to gender norms.

Generally, humans are fairly insensitive animals. Our perception is always relative and limited. We are most limited by our sense of self. It’s no wonder our sense of self-importance occupies a dominant role in how we order our world. A world founded on devaluing and exploiting other forms of being and perceiving. But in A Smeary Spot we have Mother Flawless who is a “clairvoyant psyche,” as in a state of mind (as opposed to a person who possesses this mind), as a reader of the inscrutable. She ushers us into the unknown without fear.

In this scene, Mother Flawless enters on an improvisational whim (off script), “I’m an astronaut,” declared while spinning into the cameras frame. As if commuting to work on her intergalactic office chair, she then grabs some water from the water cooler and peers through the Venetian shades before she continues with her oration on space travel. What I’m interested in is the way metaphor and allegory can make the impossible or imaginary entirely accessible, pedestrian even. I love dumb things (not as in stupid, but as in not overwrought with forethought), like the shared human impulse to scoot about on chairs with wheels. I use the exaggeration of dumb to make marginal behavior or objects central figures or points of interest. The office chair is extracted from a tool of seated labor to become a vehicle or even a spaceship. You don’t need glossy fabrication, a 2001: A Space Odyssey-style space station, to enter an alternate space-time. This work is purposefully counter to the typical high-tech narrative of a visionary future—the pinnacle of human achievement (HAL)—that will predictably be destroyed by the very ingenuity that made it possible.

[/one_half]

A Smeary Spot will be on view at Human Resources Gallery in Los Angeles, November 28 through December 17, 2017. A Smeary Spot can also be viewed in its entirety here: https://vimeo.com/140315985.

A.K. Burns is an interdisciplinary artist who views the body as a contentious domain wherein issues of gender, labor, ecology and sexuality are negotiated. Working to agitate these systems of value, Burns utilizes a broad range of methods including video installation, sculpture, drawing and collaboration. A frequent collaborator, Burns was a founding member of W.A.G.E (Working Artists in the Greater Economy) in 2008. Working in collaboration with A.L. Steiner, Burns created a video, Community Action Center (2010), reimagining pornographic cinema for womyn and non-binary bodies that screened at numerous venues internationally, including the Tate Modern, London and The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Burns was a 2016–17 Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard University and a recipient of a 2015 Creative Capital Foundation Visual Arts Award. She is represented by Callicoon Fine Arts, NY; Michel Rein, Paris/Brussels; and Video Data Bank, Chicago.

Melissa Ragain is art historian and critic whose research interests include the history of science and aesthetics, especially the historical impacts of psychology and ecology. She is currently at work on a book, “Formalism and Environmental Aesthetics after WWII,” examining the impact of art psychology on notions of form and environment in the postwar United States. She recently edited a collection of writing by the seminal new media theorist Jack Burnham, Dissolve into Comprehension: Writings and Interviews, 1964–2004 (MIT Press, 2015). She has written for Art Journal, X-tra Contemporary Art Quarterly, ARTLIES, Criticism, American Art, and Inform Magazine. Ragain was a 2010–11 Core Critical Studies Fellow at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, a 2016–17 Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard University, and a recipient of a 2016 Art Writers Grant from the Warhol Foundation/Creative Capital. She is an assistant professor in art history at Montana State University in Bozeman.

- Butler drew on Derrida’s concept of iterability to argue that performativity is also a form of citationality, in that it is never singular, but always a reiteration of pre-existing norms. Nevertheless, citation makes space for individual agency in the appropriation of normative laws. Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex (New York: Routledge Press, 1993), 12–16. ↩

- “Institutions can be built out of or through citations. This is one way of thinking about Edward Said’s argument in Orientalism (1970): as a theory of institutionality as citationality, of how Orientalists became experts on the Orient, that place imagined as being over there, through citing each other, creating a network of citations, a loop, one leading to another. When reference becomes chain, a body of work becomes wall.” Sara Ahmed, “Pushy Feminists,” Feminist Killjoys, at https://feministkilljoys.com/2014/11/16/pushy-feminists/,as of November 5, 2017. ↩

- Object Oriented Ontology is also associated with the work of Levi Bryant, and Timothy Morton. The term was coined in Harmon’s 1999 dissertation, later published as Graham Harmon, Tool-Being: Heidegger and the Metaphysics of Objects (Chicago: Open Court, 2002). ↩

- Many thanks to Richard Milligan and Linnae Wolting for their clarifying conversations on this topic. Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 152. ↩

- Marcelo Gutierrez plays “Shape-shifter as Free Radical,” and interdisciplinary artist Nayland Blake plays “Aunt Be/e as re/productive labor”. Flawless Sabrina is the only actor who performs under her chosen name–she is listed quadruply in the credits as “Mother Flawless as the clairvoyant psyche” played by “Jack Doroshow (a.k.a. Flawless Sabrina).” I wonder what to make of the difference between “as” and “a.k.a.” in Flawless’s credit line. And, I wonder what to make of the penchant for transforming the individual actors into concepts (or condensations of multiple concepts). They seem at once to be allegorical figures and alter-egos for the actors, who have their own artistic and activist practices. I take Flawless’s profusion of names as an indication of her capacity for self-invention, her gift for hanging with indeterminacy. ↩

- Karen Barad, What Is the Measure of Nothingness: Infinity, Virtuality, Justice, dOCUMENTA 13: 100 Notes, 100 Thoughts 099 (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2012), 16. ↩

- Robert Potts, “Light in the Wilderness,” The Guardian (April 26, 2003). ↩

- Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia (New York: Harper and Row, 1974), 1. ↩

- Karen Barad, “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs 28, no. 3 (2003): 828. The original quotation reads “‘We’ are not outside observers of the world. Nor are we simply located at particular places in the world; rather, we are part of the world in its ongoing intra-activity.” (emphasis in original) ↩

- T. S. Eliot “Ulysses, Order, and Myth” (1923) in T. S. Eliot, Selected Prose of T. S. Eliot, ed. Frank Kermode (New York: Harcourt, 1975), 178. ↩

- T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land (1922), stanza 5, line 340. ↩

- Guy Hocquenghem, The Screwball Asses (1973) (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), 34. ↩

- A.K. Burns and Risa Puleo “Transformation and Becomings: An Interview with A.K. Burns,” Art in America, Sept 21, 2015, at http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/interviews/becomings-and-transformations-an-interview-with-ak-burns/, as of accessed December 3, 2017. ↩