From Art Journal 76, nos. 3-4 (Fall-Winter 2017)

How do we begin to understand the crisis surrounding access to health care in American culture? This was a question I posed to prompt a conversation, in the context of curating an exhibition, In the Power of Your Care, to consider the impact of health and health care on issues of accessibility. The exhibition opened several years after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act by the Obama administration, legislation scrutinized for its costs and limitations. Public events programmed in tandem with the exhibition engaged audiences with questions about accessibility in the context of cultural institutions and of institutions in general. In the Power of Your Care was on view April 19–August 12, 2016, at The 8th Floor, the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation’s gallery in New York City. The foundation’s grantmaking, exhibitions, and public programs are geared to building community and expanding access to arts and culture, through a lens focused on art and social justice.

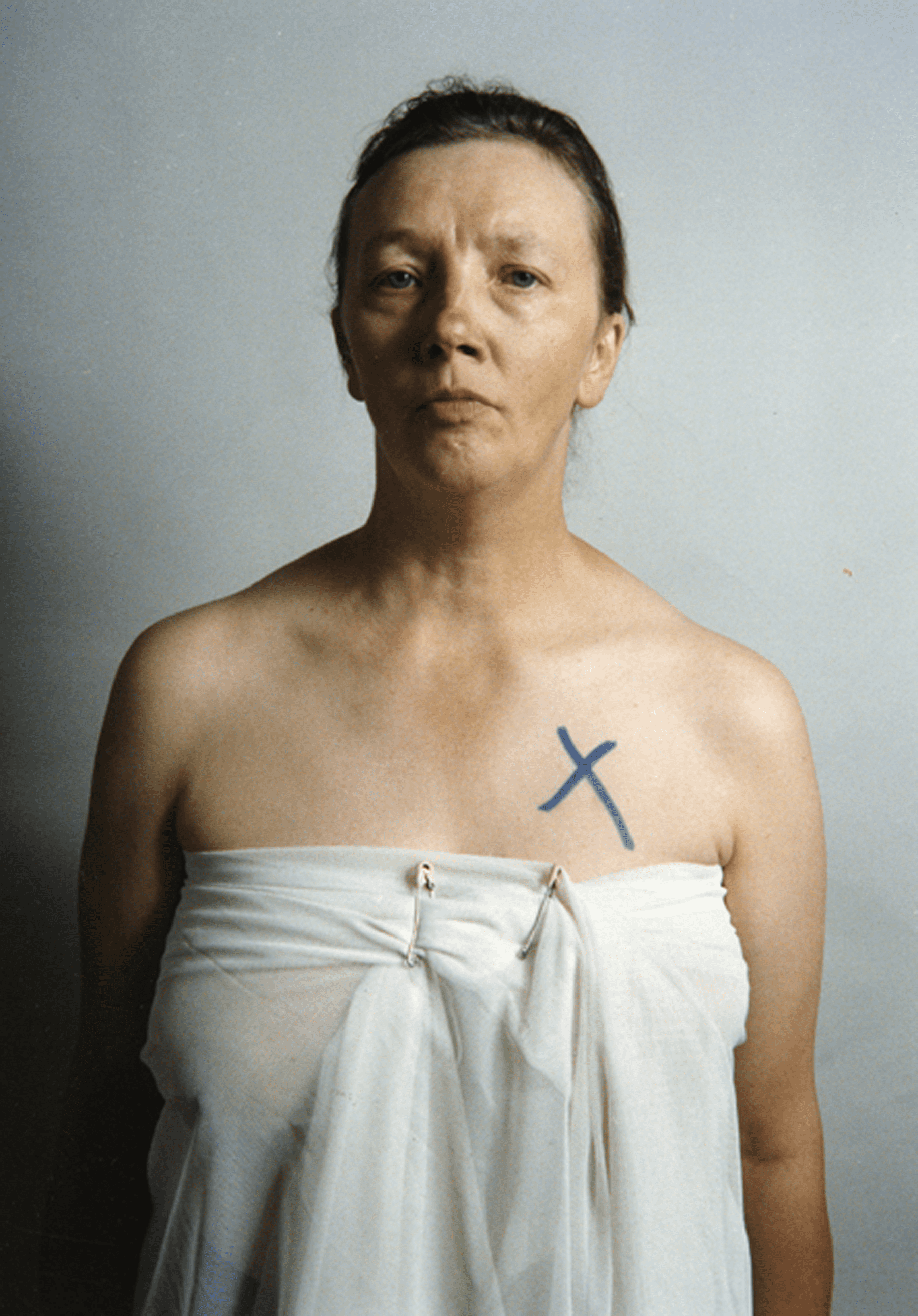

My opening question takes a cue from the late British artist Jo Spence, whose work was represented in the exhibition with two photographs, both self-portraits, one titled Final Project (1991–92), a collaboration with Terry Dennett, in which she is pictured standing over an empty grave. The second portrait, A Picture of Health: How Do I Begin? (1982–83), is from Spence’s Photo-Therapy series made in collaboration with Rosy Martin, which takes the diagnosis of breast cancer as a cue to make art about Spence’s own health and the lack of care in treatment. With the earlier image, in which the artist embodies the uncertainty of a new future, the prospect of remission or full recovery is unclear. The portrait is frontal, with an X drawn above Spence’s left breast, signaling an impending mastectomy. The artist looks directly into the camera, clothed in a sheet wrapped around her chest. In her collaboration with Martin, Spence’s portraits moved away from a traditional, controlled representation, involving the display of a specific and intentional aspect of one’s character, in other words, putting one’s “best self” forward. Instead, the two artists drew from techniques of cocounseling, psychodrama, and reframing, as a way of recognizing Spence’s new visual self as transformed by cancer, presenting that for the camera. By these means, Martin and Spence came up with an alternate way of picturing health, one that involved reclaiming Spence’s body from illness—gazing into the lens of the camera instead of looking away, a common reflex reaction to disability and illness—taking ownership of the disease, and refusing to be subsumed by the uncertainty and loss it inevitably brings.

Visual artists have long sought to understand and represent the human body and its conditions. From Leonardo da Vinci’s Anatomical Manuscripts (1510–11), which were the first to visualize the skull, spine, and heart, to Thomas Eakins’s Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (Gross Clinic) (1875) and his many paintings of surgical procedures, artists have continually developed new ways to express the human condition, whether it involves detailing the human form from an external perspective, or the body as experienced from within. In the Power of Your Care wove together narratives of health as an investigation into the politics of care in the broader context of American culture, in which health care policy itself has not historically been considered necessary, adequate, or inclusive. In the United States, the health care system is not yet designed to provide all-inclusive coverage without some form of paying in. Those who go without, or who have limited coverage, are subject to a certain level of precarity and may live in an environment of limited accessibility, without the support necessary to participate fully in daily life. The conditions of precarity can lead to a circular dynamic. If one survives trauma and disease without sufficient support, these conditions can develop into further instability, making access to care all the more elusive. The exhibition title In the Power of Your Care included the words power and care, specifically your care, as a way of implicating the viewer and the community surrounding the exhibition in a dialogue about our responsibilities in caring for ourselves, and one another.

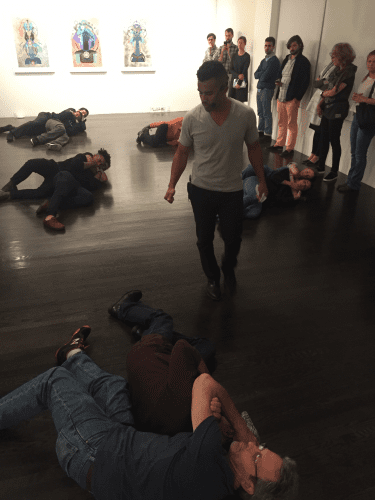

In the cultural sector, disability is a facet of diversity, yet demographic analyses are generally fixated on statistics related to race, gender, age, and economic status. The diversity of an audience that participates in cultural programming is assessed through tracking information about those who show up, who are able to gain access to the museum, theater, gallery, or park. Those who do not physically participate are not counted and, therefore, often left out of the discourse about diversity, which in recent years has become increasingly focused on the impacts and racist implications of overzealous policing in American cities. Artists like Shaun Leonardo have begun making work that engages with trauma experienced by people of color, especially young men of color. In urban environments like New York City, stop-and-frisk policies were upheld for many years, unduly criminalizing immigrant residents and communities of color. Leonardo’s project I Can’t Breathe (2015) is an interactive performance in which he guides the audience through a participatory self-defense workshop, designed to teach participants how to survive a chokehold. The police chokehold marked the end of life—the last breath—for Staten Island resident Eric Garner, whose crime was illegally selling individual cigarettes. Originally staged at Smack Mellon, a nonprofit gallery in Brooklyn, Leonardo’s I Can’t Breathe performance was part of an exhibition titled Respond, organized with Smack Mellon resident artist Dread Scott as a collective response to recent deaths at the hands of police. At The 8th Floor, I Can’t Breathe was presented in October 2015, during the exhibition Between History and the Body. The performance led participants through self-defense training Leonardo designed to demonstrate the power relations between law enforcement and young men of color, guiding participants to make space to breathe rather than attempting to pull out of the chokehold. The physical performance was immediately followed by a discussion between Leonardo and the clinical psychologist Isaiah Pickens, speaking about the trauma that people of color carry with them. Pickens spoke specifically about how trauma impacts the degree to which young people are able to pursue opportunities, educational and social, later in life. Embodying trauma, both lived and historical, can contribute to day-to-day anxieties that can ultimately have a negative impact on health and longevity.

A common critique of this type of performance artwork as a public program is that it takes place in a relatively private cultural space, which begs the question: how can such an activist artwork reach a wider audience? In Leonardo’s case, the artwork was funded by Franklin Furnace to travel to different schools and community spaces where young New Yorkers could take part in the workshop, with its practical training for how to de-escalate potentially violent situations with police and other authorities, and how to safely survive a chokehold.

Although Leonardo’s project helps foster a sense of agency on the part of the young participants he engages, equitable access to arts and culture across racial and economic divides remains elusive. Similarly, physical access and mobility in relation to disability are often unaddressed institutionally. Even with the cultural sector’s current obsession with ideas of diversity—cultural, linguistic, racial, gender, and other factors of identity politics—access for those with disabilities is often overlooked in conversations about cultural participation. My own awakening about accessibility occurred while commissioning public art for civic spaces in New York City through the city’s Percent for Art program. In 2014, the first year of Bill De Blasio’s term as mayor, there was a marked increase in consciousness and implementation of inclusive design guidelines for the construction of public spaces where works commissioned by Percent for Art were sited. This shift meant that the process of soliciting proposals for artworks required a greater awareness about creating different options for experiencing artworks, so that a viewer in a wheelchair could have a comparable, if not identical, experience of an artwork as someone without a physical disability.

My perspective on accessibility was most poignantly affected in the Southern California desert that summer, at the opening of the artist Halsey Rodman’s Gradually/We Became Aware/Of a Hum in the Room (2014). The architectural sculpture was installed on the property of the High Desert Test Sites (an experimental site in the desert established by artists, dealers, and collectors, spearheaded by the artist Andrea Zittel) and was commissioned by Art in General, a New York City–based alternative space. No signage indicating the location of the artwork could be found, aside from a group of cars in a sandy clearing. My understanding of the lack of consideration for access was heightened by the fact that I was there with my mother, who is always interested in taking exploratory road trips, partly because walking and standing for long stretches of time (basic requirements while visiting larger museums) had become difficult for her after treatment for lung cancer. Having curated many outdoor site-specific projects myself, I was already aware of the importance of preparing visitors and viewers for what’s ahead.

One of the misconceptions about public art and land art is that this type of art is inherently accessible by virtue of being situated in an open space without walls. Yet, accessing nonurban public art in a location like the High Desert Test Sites requires transportation as well as a hardiness to make whatever physical trek is necessary to reach the artwork in question. The press release announcing Rodman’s installation might have read: “This artwork is installed in the desert and will require visitors to walk three quarters of a mile.” The omission raises questions about how prepared Art in General—and presenting organizations in general—need to be in facilitating visitor access. If they were to acknowledge the distance one must walk, between the dusty parking area and the artwork, would that implicate them in providing assistance to visitors with limited mobility?

Perhaps there is an allure to creating artwork that is hard to reach. In 2010 Miwon Kwon presented a talk at the New Museum in New York City, in advance of an exhibition she was in the process of cocurating with Phillip Kaiser, Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974, for the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. Kwon spoke about the journey required to experience land art as being part of the artwork, and in the conversation that followed, at least one member of the audience questioned the economics of the journey, suggesting that it was at odds with the idea that land art is implicitly public. One misconception about artworks installed outdoors, in spaces that appear to be public, is that they’re intended for a wide audience, or that inclusive design for access by individuals with disabilities is even a consideration in their commissioning and siting.

Using Art in General’s commissioned artwork at the High Desert Test Sites as an example reveals the fluidity of mobility and disability in connection with health. Traveling to the site and then walking through the brush leading up to Rodman’s sculpture in the desert was a challenge for my mother not because she is a person with a permanent disability, but because of health conditions that fluctuate, preventing a certain amount of access, depending on the terrain and the day.

How are we to think through our own responsibilities to individuals with disabilities without imposing societal ideas, many of them generalized and misguided, about disability? Also included in In the Power of Your Care was Carmen Papalia’s Open Access Banner (2015), a set of guidelines, handwritten on canvas, installed above the gallery’s front desk, thus confronting the viewer about the institutionalized culture surrounding accessibility and policies conceived to assist individuals with disabilities. Without using the word “disability,” Papalia establishes the fluidity inherent in accessibility as a community-based framework: the Open Access text “interrupts the disabling power structures that limit one’s agency and potential to thrive. . . . Open Access relies on who is present, what their needs are, and how they can find support with each other and in their communities. It is a perpetual negotiation of trust between those who elect to be in support of one another in a mutual exchange.”1

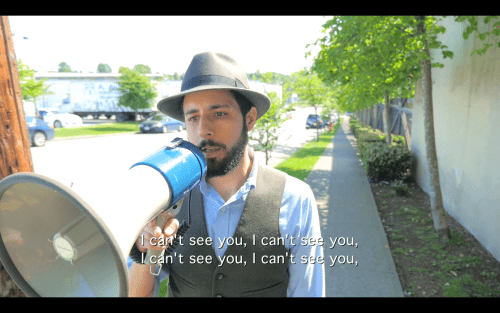

Papalia’s proposition for Open Access is the essence of a responsive and engaged community, one that encompasses flexibility, agency, and a “complexity of embodiment.”2 Another way he promotes this is through participatory performances, in which he leads groups on nonvisual or blind walks, using a cane to find his own way. Presented in multiple cities and at least one rural location, the performances enact the interdependencies required for the principles expressed in Open Access to work. During summer 2016, the Rubin Foundation hosted at The 8th Floor a series of workshops and panel discussions on cultural accessibility, which included walks led by Papalia. The participants in these walks are asked to keep their eyes closed and rely on one another to find their way through public spaces: sidewalks, streets, and parks. The experience transformed my own understanding of my senses, recalibrating my relationship to the physical world: the pavement, scaffolds, curbs, and landscape design, not to mention vehicles and pedestrians that were in constant motion around us. In his video White Cane, Amplified (2015), Papalia gives up his white cane (a mobility tool used by people who are visually impaired) in favor of a megaphone. “Stumbling upon the term non-visual learner allowed me to recognize the value in my process of gathering a sense of place and was the catalyst for a body of work that realizes disability experience as a liberatory space.”3 White Cane, Amplified follows the artist along the busy streets of Vancouver, using sound and voice instead of touch to find his way, calling out to passersby to help him cross the street. The video turns the project outward, hailing an unwitting public that is forced to take a position and decide whether to ignore or engage with Papalia, and his vulnerability in the urban landscape.

Another model of care that speaks to the generosity of Papalia’s Open Access is Simone Leigh’s Free People’s Medical Clinic (2014), a project that was also represented in In the Power of Your Care. Leigh’s contribution to the exhibition consisted of ephemera related to the Free People’s Medical Clinic, which points to a need for more dignified health care options in underserved communities. For the project’s first iteration in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, Leigh revisited the often overlooked health care efforts organized by black women for the African American community during the nineteenth century, as well as the Black Panthers’ community-based health care programs that operated from the 1960s to the 1980s. The clinic in Bed-Stuy was staged in the former home of Dr. Josephine English, the first African American woman to establish an OB/GYN practice in New York State, in the 1950s. In the clinic, the artist and her collaborators hosted workshops in acupuncture, massage, yoga, dance, and other healing practices for community members and visitors to the neighborhood. Leigh has described the project as being inspired in part by the tragedy of Esmin Elizabeth Green, who died in 2008 at the age of forty-nine in the emergency room of Kings County Hospital, having waited twenty-four hours to see a doctor. In an essay about the Free People’s Medical Clinic and Green’s death, Naomi Jackson describes the surveillance footage documenting Green’s death, stating that “Waiting may have killed her.” The project and Jackson’s essay make the case that it is time that women of color receive equal care.

The projects by Spence, Leonardo, Papalia, and Leigh each work to externalize the precarities and vulnerabilities of being othered in relation to mainstream cultural experience. In their address to the public (both specific and general), these artists locate liberatory spaces, where collective experience, in many of its distinct forms as defined by health, race, mobility, and disability, can be better understood and ultimately supported, whether through policy change, grass-roots organizing, or artistic projects presented to an audience of interested parties or in public spaces. The visionary thinking of these four artists lies in their understanding of the intersectional nature of identity, suggesting that no matter where we begin, whatever our cues, we must listen with all of our senses and faculties. It is with these perceptive capacities and intentions that diversity can begin to be understood and engaged, personally and professionally, individually and collectively.

Sara Reisman is the executive and artistic director of the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation. From 2008 to 2014, she was the director of New York City’s Percent for Art program at the Department of Cultural Affairs, 2008-14, where she managed more than one hundred public and civic commissions across the five boroughs. Reisman was curatorial consultant for public art in support of the Queens Museum of Art’s community development initiative in Corona, Queens (2008-9), and has curated exhibitions for the Queens Museum of Art, Socrates Sculpture Park, the Cooper Union School of Art, the Philadelphia Institute of Contemporary Art, Momenta Art, and Smack Mellon, among other venues.

- Carmen Papalia, Open Access, 2015, alternately titled For a New Accessibility, conceptual object, dimensions variable. For the full text, see “Carmen Papalia: For a New Accessibility,” at http://the8thfloor.org/open-access-workshop-with-artist-carmen-papalia/, as of November 2, 2017. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Carmen Papalia, “You Can Do It with Your Eyes Closed,” Art21 Magazine, October 7, 2014, at http://magazine.art21.org/2014/10/07/you-can-do-it-with-your-eyes-closed/#.WfrLMBNSyT8, as of November 2, 2017. ↩