From Art Journal 77, no. 2 (Summer 2018)

In an article titled “The Photograph as a Receptacle of Memory,” the Jamaican-born artist Albert Chong asks, “Where are the great photographs of the Caribbean, the iconic pictures that have become part of the visual memory of the people and their struggle for everything from freedom to independence and the construction of nations from slave colonies? . . . Where are the sadly, or gladly, profound photographs to be found”?1 In this essay I engage Chong’s lament about the dearth of iconic photographic images in the Caribbean, which comes out of his own exploration of questions of memory, temporality, and photography’s ghostly remains in his artistic practice.2 I take up Chong’s observations on photography and iconicity as a starting place in my consideration of one aspect of the afrotrope, a neologism that aims to give descriptive form to the tropes that are transmitted and translated across African diasporic populations, and across time, space, and media. The afrotrope refers to “key recurrent visual forms that have emerged within and have become central to the formation of African diasporic culture and identity. . . . [They] have a profound effect on how black subjects imagine themselves and negotiate technologies of visual transmission.”3 Such tropes—whether the regionally distributed pencil drawings of Rastafarian subjects by the Jamaican artist Ras Daniel Heartman from the 1960s and 1970s or the globally disseminated photographs of the Olympian sprinter Usain Bolt striking a pose in 2008 (to use two examples from Jamaica)—become central in the formation of modern African diasporic communities. I seek, more specifically, to investigate the role of photography and its absence in the formation of the afrotrope. How might the absence or disappearance of certain types of photographic representation take material form over time and across African diasporic communities? How have African diasporic subjects used and refused what the film and photography historian André Bazin described as the “ontology of photography,” an understanding of photography as indexical, of the photograph and the object it pictures as “sharing a common being,” just as one might imagine the relation between a fingerprint and a finger, to use Bazin’s example?4 What are the intertwined ontologies of photography and blackness that come to the surface when considering the afrotropic?

I explore these questions by concentrating on an image that Chong singles out as one of the exceptions to photographic absence in the Caribbean context—a widely reproduced photograph used in and as a poster for the 1972 Jamaican-produced independent film The Harder They Come. The film, directed by Perry Henzell and cowritten by Henzell and Trevor Rhone, is often identified as the first Jamaican-produced feature film about the island’s black populace, one in which local moviegoers could catch glimpses of themselves as modern subjects of the big screen. The film was based on the real-life exploits of Ivan or Ivanhoe Martin, also known as “Rhygin” and “Rhyging,” who since the late 1940s has been variously described as a fugitive, a two-gunned killer, an escaped convict, a social bandit, and a folk hero.5 This essay focuses on the image from The Harder They Come but ultimately returns to the history of Martin and his complex relationship to photography to explore how the image of the 1940s persona was reconfigured over time, through the reproduction, restaging, and rephotographing of his image, as well as through stories about the creation and circulation of his photographs. I make the case that the specific social, political, and institutional conditions that affected Jamaica’s African diasporic communities in particular, from colonial and postcolonial histories of archival disappearance to local histories of capture and fugitivity, all contributed to the photograph from The Harder They Come and how the image was subsequently visualized, embodied, and reperformed across time, media, and geography.

The history of Ivanhoe Martin’s representation and its reconfiguration, I argue, evince a photograph that was decades in the making and that emerged three decades after Martin first evaded police capture. His photograph was obfuscated by authorities and by “guardians or sentries” of the archive, to use Jacques Derrida’s phrasing, in colonial Jamaica, yet developed and then proliferated over time and across space.6 Martin’s image came into being through and encapsulates counternarratives, or what might be described as shadow histories of photography.7 The representation was about a literal and figurative outrunning of colonial uses of photography to bring about arrest, and reveals a certain rejection of the indexicality of the photographic form. Its history of latency and emergence, disappearance and appearance, its taking on and denial of form over time, and its reconfiguration and expansion of the matter and meaning of the photographic all underscore the representational characteristics and possibilities of the afrotropic.

“Fugitive” and “Star”: Photographic Presence and Absence in The Harder They Come

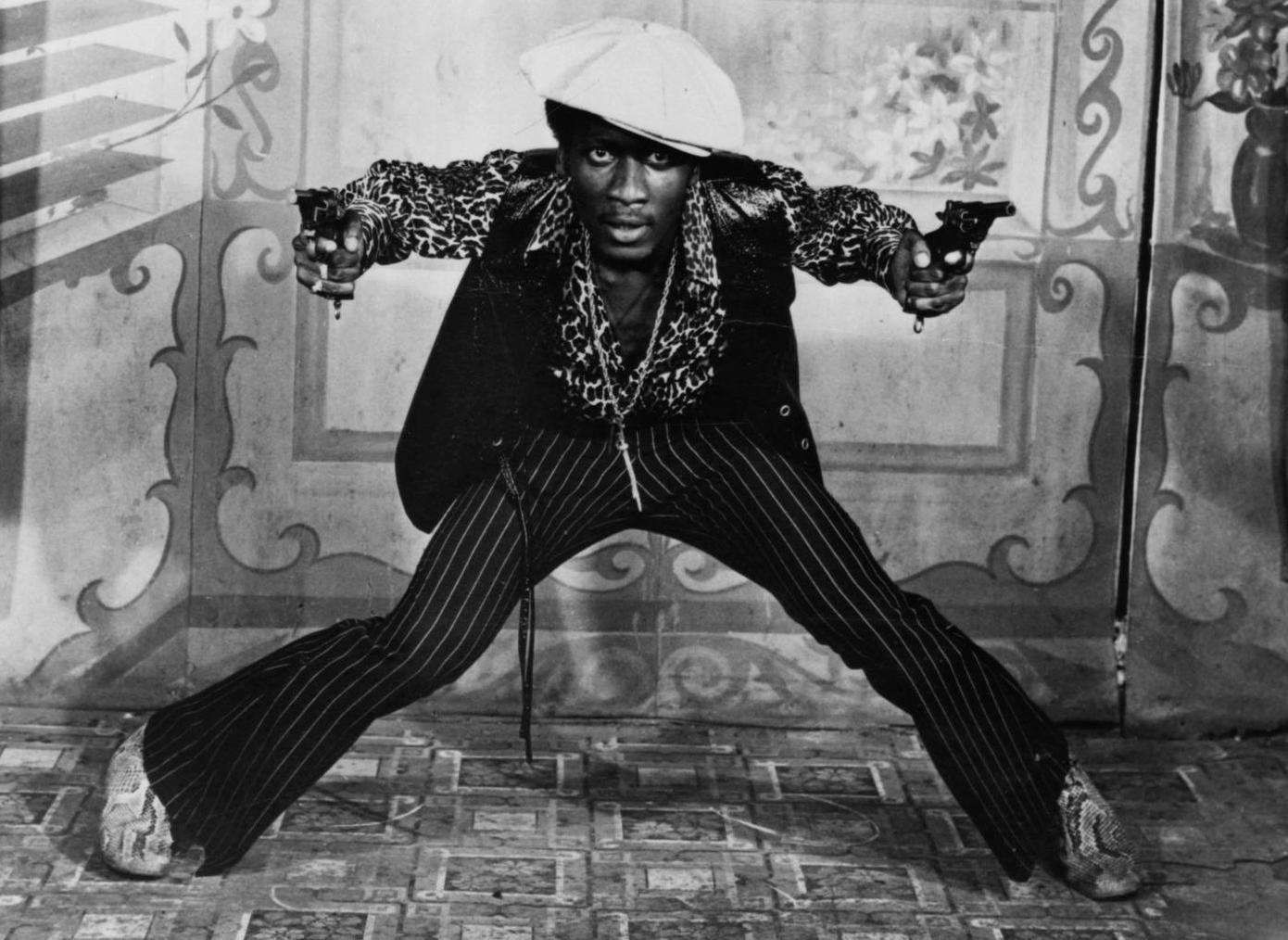

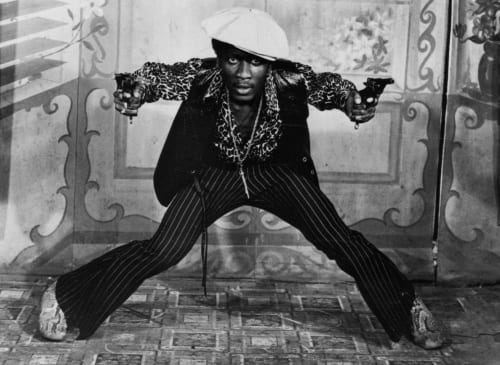

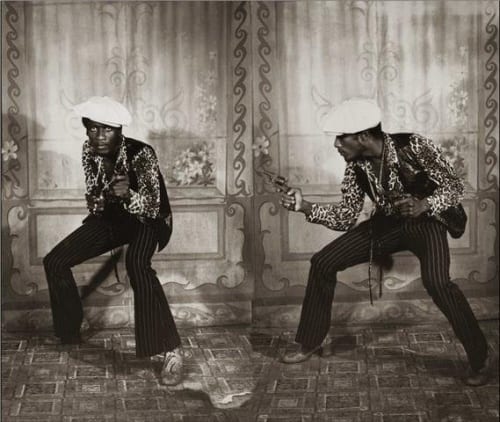

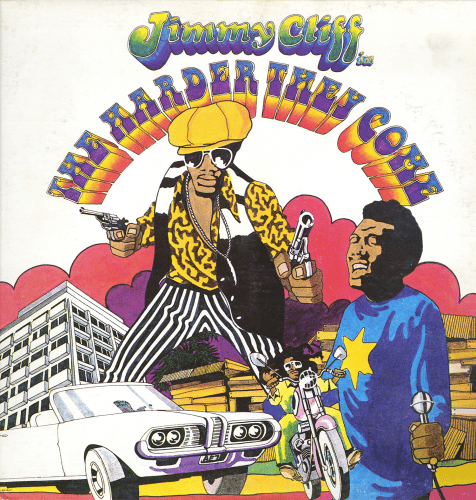

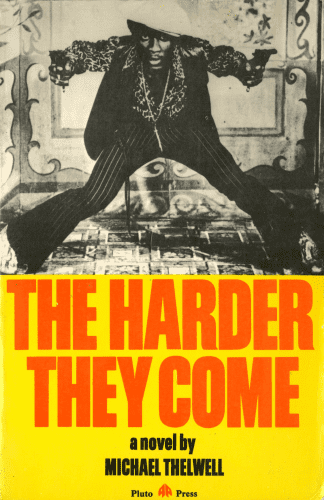

Chong highlights a photograph of the Jamaican ska and reggae singer and musician Jimmy Cliff, who played the role of Martin in The Harder They Come.8 Martin’s character is referred to by his first name Ivan in the film (accordingly, here I use Ivan to refer to the character in the film). The image, by an unidentified photographer, shows a closely cropped image of Cliff, standing dramatically with two guns aimed with an uncertain certainty at the photographer.9 The image pictures a dark-clad, fashionably dressed character posing before a light, hand-painted photography studio backdrop. Cliff strikes a stance in a leopard-print long-sleeve shirt, leather vest, black pinstriped pants, alligator-skin shoes, and a fashionably askew white oversize African-American “poor boy” cap.10 The photo presents many tropes and sites of self-fashioning, of fictive self-invention, from the photography studio (rendered with such care), the figure’s pose (inspired by Hollywood and Italian spaghetti-western filmic genres), and his clothes (several items of which suggest the notion of another skin—leopard, alligator, leather), to the time and space of the photograph and the film themselves.11

The image captures a pivotal moment in The Harder They Come when Ivan, wanted by the police after a brazen shoot-out, decides not to withdraw from public view but to go into a local photography studio and have portraits taken. At this point moviegoers have seen Ivan arrive from the Jamaican countryside, set on being a reggae singer, only to have his efforts to achieve fame and fortune undercut by a greedy record producer, a corrupt police force, criminal drug-trading gangs, and a covetous coworker, who tries to steal his bicycle. Ivan slashes the man with a knife, wounding him, and so begins his life on the run.

In the photography studio Ivan strikes a number of poses, with the camera lingering on, and helping to produce, what would become the iconic filmic image. The cinematographer shot the studio session in part from the perspective of the photographer, framing inverted images of Ivan through his viewfinder. The scene foregrounds the medium of photography and the character’s process of performing for the camera as intrinsic to Ivan’s self-fashioning, his emergence as a ruud bwai (rude boy).12 The reggae tune “007 (Shanty Town)” animates the photo shoot, which is interspersed with flashbacks to formative moments in the film. The editing of the scene, which features a montage of different images of Ivan posing in quick succession, gives the still photographs a distinctly performative dimension. The image of Cliff is brought to life by sound and movement.

Ivan, in the next scene in the film, has his photographs delivered to local newspapers, mocking police efforts to identify and capture him. Henzell would explain that the filmic portrayal of Ivan’s photography session and efforts to publish his images stemmed from Martin’s promotion of himself not as a “fugitive” but as “a star.” “The calls to the radio station, the photographs at the Gleaner, the photographs in the paper . . . all that stuff, is what he did,” Henzell would reiterate.13

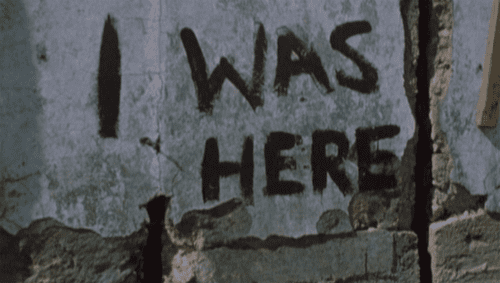

Ivan in his filmic incarnation flaunts his visibility through photography, while simultaneously touting his ability to disappear. In the film, the slogan that captures Ivan’s elusiveness is “i was here but i disapear.” The words appear spray-painted on the walls of Kingston’s urban communities. Newspapers from the 1940s reiterate this sense of Martin’s visual and physical elusiveness. The Kingston-based Daily Gleaner, for one, referred to Martin as a “phantom killer.”14 Picturing an image of the spot where Martin had reportedly mortally wounded a man, the paper rather dramatically detailed that the victim was killed by “a bullet from a revolver in the hand of a man who came out of the dark and disappeared into the dark.”15 Martin assumes a disembodied presence in the account, a hand that appears and retreats into darkness. Another report in the same newspaper cited “two appearances” by Martin in Kingston on September 5, 1948, but noted that despite prompt police action, he “vanished into the underworld from which he had emerged.”16 When bloodstained clothes suspected of belonging to Martin were found, they seemed evidence that he had disappeared, shedding them like a second skin.17 Other accounts cited “the notorious desperado’s” ability to “disappear,” “slip away,” and “reappear.”18

Martin’s history and story of stardom as retold in The Harder They Come is importantly bound to disappearance. Historically, since at least the 1950s, light and visibility, as well as photography and the circulation of images in media, have been intrinsic to the machinations that produce Hollywood “stars,” a process Martin may have witnessed in the cinema in Kingston.19 Martin engaged, retreated from, and reengineered the celebrity spotlight, inserting himself into a system that typically excluded black subjects. His public persona was constituted, though, through light and shadow, photographic proliferation and visual retreat, visibility and disappearance. Disappearance in the case of Martin is defined not in a conventional way as “not being visible or passing from view nor ceasing to exist” (as the Merriam-Webster Dictionary characterizes the word), but as a state of visibility negotiated through photography in which there is a heightened presence, a replication of the individual through photography, and a relational, physical, bodily absence. As Martin’s presence took increased visual form and proliferated across the media and public space, his physical presence seemed to diminish or to take on new forms, such as words that marked his absent presence across the landscape. As Spotlight magazine so succinctly put it, “Martin seemed to be here, there, everywhere—and still nowhere.”20

Photography has been employed as a medium to “arrest” those defined as criminal since the 1880s in Britain and France (and their colonies), as Allan Sekula and other scholars have documented.21 Criminologists used identification photographs—in tandem with systems of archiving, “bureaucratic clerical-statistical systems of intelligence,” and emergent apparatuses of truth—to facilitate the targeting and arrest of pictured subjects. They also employed different strategies involving photography to visualize what a criminal looked like, to arrest through the photographic print the surface traits of types of people deemed aberrant to civil society.22 In Martin’s history and filmic depiction (I disentangle the two explicitly below), the authorities could not deploy photography—initially, at least—to apprehend someone deemed an outlaw, or even to visualize the criminal subject. Martin’s appearance, his physical body, seemed something he could slip out of. When the police sought to apprehend him he simply was not there. Invoking the very opposite of the matter of photography, the inscription of light on a recipient-plate, newspapers describe Martin as drawing back into the shadows, his presence marked by darkness, by the absence of light and legibility.23

Afrotroping: The Transnational and Transmedial Circulation of The Harder They Come

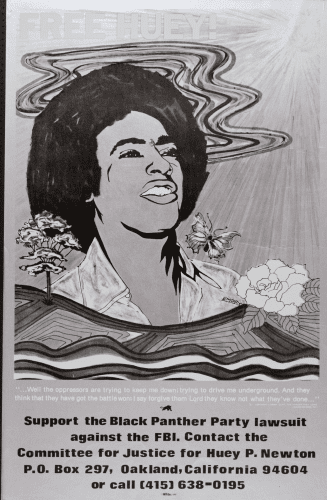

The image of Cliff would take several different visual forms as it circulated across and beyond African diasporic communities through the transnational distribution of The Harder They Come and its soundtrack. The film, after opening to rave audience responses in Kingston, drew a “big turnout” when it premiered at the Embassy Theatre in New York on March 12, 1972.24 The movie subsequently opened in Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Brixton, UK, and in cities in the Caribbean. The film and its soundtrack have been credited with introducing reggae to audiences transnationally.25 The Harder They Come was initially marketed (against the wishes of the director) as a part of the Blaxploitation genre, a type of action film that often followed the exploits of hyper-virile black male heroic figures fighting different forms of oppression.26 Blaxploitation films tapped into the diverse political, social, and artistic movements and groups associated with black nationalism and anticolonial movements taking place internationally in the latter half of the 1960s and early 1970s. The Harder They Come was projected at a historical moment of black political mobilization, radicalization, and internationalism, and at a time of deathly reprisals against the leaders of these movements by the state, from Oakland to Brixton. Tellingly, lyrics from The Harder They Come would appear on a poster seeking to raise funds for the legal cause of the Black Panther Huey Newton against the FBI.27 The poster evinces how the film became a soundtrack for contemporary black figures across geographic locations with shared histories of fugitivity, who were pursued by the state, the FBI, the law, and antiblack racism.28

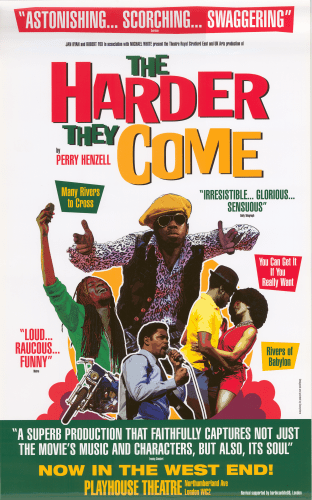

It is not clear when the popular image of Cliff posing in the photography studio started to circulate, to proliferate, to sediment into the iconic image of the film. The well-known photograph of Cliff at some point was reproduced on a poster for the film. It was this form that Chong described in his article. The popular image was translated into an illustration for the cover of the film’s soundtrack release. The iconic photograph of Cliff, in an even more cropped form, also served as the book cover of The Harder They Come when Michael Thelwell turned the movie into a novel in 1980. Versions of the photograph were reincarnated for posters for the film and even for a 2006 musical based on The Harder They Come at London’s Playhouse Theatre. In a version of the poster created by the UK-based graphic designer Yasheer Mohamed in 2010, the image of Cliff posing appears lifted from its studio surroundings and multiplied three times over in different colors. Shifts in color, to other primary colors, and in scale convey a sense of dynamism, movement, and flux—which was so integral to the cinematic staging of the studio session—and which encapsulates too the image’s movement across time and space. Reminiscent of the repetition of images in Pop art (as popularized in Andy Warhol’s work), the shifting and reappearing subject of Ivan in this work seems in keeping with the history of Martin and his representation. The image circulated transnationally through a range of media (accompanying a film, its soundtrack, a novel, and a play) and across visual forms (from photography to a graphic image) and material forms (from a poster to a book cover). One might say that it even traveled between these forms (with the image of Cliff as both a photograph and a film still, for one, or the poster from the musical as both a theatrical reenactment and a photograph), shifting into and remaining at the interstices of multiple representational states.

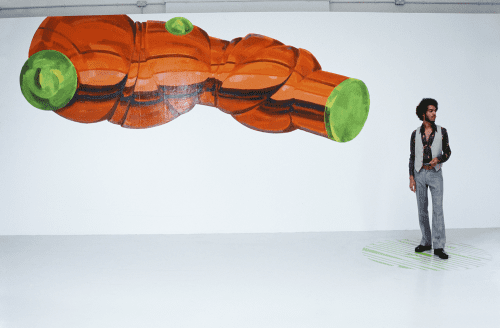

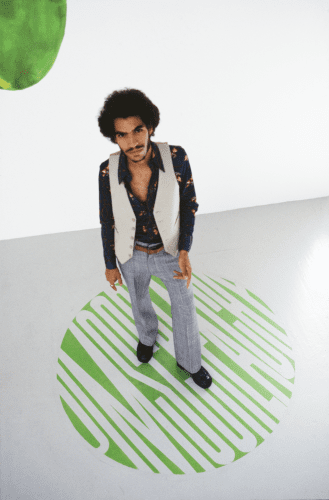

Several contemporary artists—from the Ghanaian-born, Britain-based artist Hew Locke to the Jamaican-born, Canada-based artist Charles Campbell—took up the photograph from The Harder They Come, and through their work the image circulated across geographies and over time. Artists turned to the 1970s image of Cliff in part to conceptualize the presence and return of the past, at times highlighting the material accretion of time through the image. Campbell, hitherto a painter, began doing performance art to give the image of Cliff performative life in his Jim Screachy work in 1999, a piece produced as a final master’s degree project at Goldsmiths College in London. A photographic document of the performance (the artist’s video documentation of the performance is lost) shows Campbell striking a pose with one finger suggesting a gestural gun. On the floor is a conceptual rendering of a time machine, one that allows Martin (and his reenactment) to reappear across time and space.

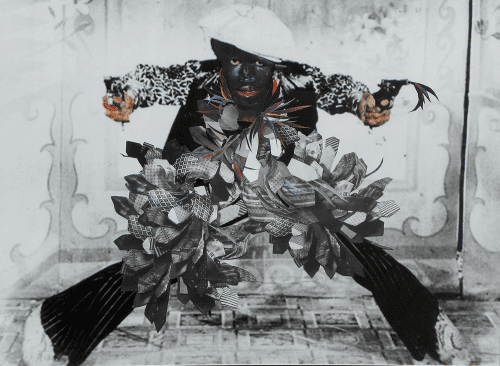

The Atlanta-based Jamaican artist Cosmo Whyte also used the image as the basis of his collage work Shotta (2011). Composed of an archival photographic print of the photo from The Harder They Come adhered to matte board, the work features Cliff posing augmented by black paint on his face, overpainted on the photograph. In the work Cliff dons a colorful costume composed of strips of fabric, made of the material from ties (from family heirlooms and found objects), collaged on the image. The blackened face, which materially resonates with the paint used in blackface minstrel performances in the United States and the Caribbean, also recalls masquerading practices in Jamaica, such as Jonkonnu. The work engages a number of pasts in its subject matter and form. By highlighting masquerade practices (with their links to West African traditions), through the use of ties (representing generational ties between men and an inheritance of modern Western attire), and through the photograph from the 1970s (which the artist viewed as an enduring and formative representation of masculinity in Jamaica), the work lingers on and manifests a material accumulation of multiple pasts. This description of some of the ways in which the photograph from The Harder They Come has been returned to, reembodied, and reperformed highlights the longevity of the afrotrope and its emergence across different forms. The image foregrounds how the afrotrope does not simply reappear over time, but is about time, its passage and return, and its material traces.

“A Ghost of an Image”: Martin’s Poor Photographic Remains

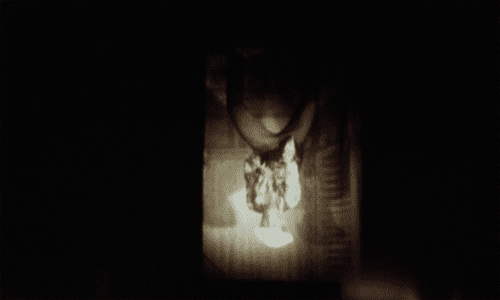

The photo of Cliff is so commonly reproduced and visualized and the story of Martin so many times told and performed that few have lingered on or returned to the historical images and archival traces of Martin.29 An image that circulated in the local Daily Gleaner newspaper on September 2, 1948, purporting “here is the wanted man—ivan martin, alias ‘Rhyging’ alias ‘Ivan Brown’” may have inspired the iconic image from The Harder They Come. In the representation a figure, occupying the majority of the picture’s frame, stands with what appears to be a gun in his right hand. He casually wields the object across his body, which is attired in light-colored, loose-fitting clothing. The photograph would have been more legible to newspaper readers in the 1940s and may have been more visible to the makers of The Harder They Come, but reproductions of the image that are most readily available in the archives and on the internet are only partially legible. The “wanted” ad picturing Martin, which is no longer in the Daily Gleaner archives, was likely destroyed by a fire that decimated much of the newspaper’s visual collection in the 1960s. The image of Martin that is most commonly reproduced is a digital version of a microfilmed image of the photograph that was reproduced in halftone in the newspaper. The photo evinces how different technologies of reproduction and of preservation can also produce image loss and deterioration. Many details, like the figure’s face and clothes, take the form of indistinct silhouettes, shadowy, if not ghostly, presences. The technologies of mechanical reproduction and archiving also produce surplus visual texture. Parts of the contemporary manifestation of the image have an inkblot appearance, a saturated blackness which calls attention to that which is so visibly absent in the image. The figure merges into the background’s shadows and light, appearing like the Daily Gleaner’s characterization of him as a phantom. The image recalls the filmmaker Hito Steyerl’s description of a poor image, an image or film that has been circulated at low resolution so many times over that its quality is “bad,” “its resolution substandard. . . . It is a ghost of an image.”30

In the remainder of the essay I want to linger on the space and time between the nearly disappeared image of Martin from the 1940s and the iconic image of Cliff from the 1970s (which is still widely reproduced). The connections and disconnections between these images, their material continuities and discontinuities, their moments of appearance and disappearance, reveal something about the temporality of the afrotrope, and about how photographs—when used by African diasporic communities—can literally develop over time, in a future time, while also occasioning a perpetual return to a past.31

The histories of Martin’s image offer a counterpoint to Steyerl’s understanding of the speed, the temporality, of poor images. Steyerl makes the case that as poor images lose matter they gain speed, compressed low-resolution images travel more quickly in time and across digital space.32 Bad resolution and the image’s abstraction are material consequences of the poor image’s spread. In the case of the Martin photograph from the 1940s, however, its poor quality is the result of poor processes of digital preservation and circulation that over time did not make the image widely available, but secreted it away. Its history of disappearance was linked perhaps to the degraded value of its subject.33 The microfilmed image materially manifests the affective marks of disappearance, of the histories that obscure certain photographs from view. The poor status of the Martin image arguably slowed the image down, leading to its slow accretion, its waiting, its surfacing, its gradual development, over time. The photograph of Cliff from The Harder They Come is one manifestation of Martin’s reemergence, his ability to disappear and reappear over time through photography and other visual and performative means.

The image of Cliff is an example of a type of representation that comes into being through and despite conditions surrounding African diasporic communities that might cast aside black histories and their visual traces. The photograph from The Harder They Come is wrought at the intersection of the histories that are known through oral histories (which were the basis of The Harder They Come) and the histories that are not known, that are unrecoverable in the shadows of the photograph.34 The spaces of disappearance become the spaces inhabited by new histories, new representational forms, new interpretations. The photograph is an example of what Achille Mbembe describes when he notes how the material destruction of archives can add to their content, their conscription in the register of imagination. Being “removed from sight and interred once and for all in the sphere of that which shall remain unknown” allows a “space for all manner of imaginary thoughts.”35 This site of invention at the interstices of histories of disappearance is precisely the space of the afrotropic. The afrotrope is the form that remains latent, a form long prevented from taking form, that social circumstances prevent from coming into being. It waits for the right set of circumstances to come into visibility, to appear and disappear.

The history of Martin, what is known and what remains unknown about him, highlights the sites of imagination, memory, and history that generatively come to fill the spaces of disappearance. I maintain that the numerous reincarnations of the photograph from The Harder They Come do not simply mark a return to Martin’s 1940s photograph after the fact, but constitute, to quote Marilyn Ivy, “a repetition that becomes its own spectral origin.” As Ivy further contends in her consideration of discourses of the vanishing, “The second event—when the originary moment emerges as an event to consciousness—is thus the first instance: the origin is never at the origin; it emerges as such only through its displacement.”36 In the case of Martin, the second photograph, the image of Cliff as Ivan, has displaced the first image of the man reproduced in the newspaper, becoming a unique creation, an image circulating visually and orally with distinct embellishments that are not verifiable in the archival sources on Martin.

“Wha, No Pics.?”: Martin’s Missing Police Mugshot

Newspaper archives and court records allow some limited access to Martin’s history, revealing a more complicated story than the one told in The Harder They Come and scholarly sources, especially as that history relates to photography. At the root of the history, perhaps fittingly, is a missing photograph, one that was absent from the British colonial criminal archive in Jamaica when the manhunt for Martin first began on August 30, 1948. As a special reporter for Public Opinion newspaper detailed, after Martin escaped, “I am able to reveal that the Criminal Investigation Department had no photograph of ‘Rhigin’ in their Rogues Gallery although he was a convicted criminal and was known along [sic] as dangerous and violent.” “Why wasn’t Martin photographed as part of the routine by which all long term prisoners are photographed and finger-printed,” the reporter further queried. “These are important questions being asked by those who know the facts about Martin’s escapades in the prison and who know that these vital records are not in the possession of the police.”37

The reporter noted that all the Criminal Investigation Department had to go by was a “pen-portrait of the two-gun killer” and that they were drawing on every man in the force who knew “Martin by sight.”38 Tellingly, the reporter viewed the pen portrait—likely an image sketched by someone in the department— as an impoverished representation and record. Spotlight newsmagazine would similarly deem the earliest representations of Martin as “inadequate, misleading, and uncertain,” and questioned why the police did not “mug” Martin, as they had “expensive photographic equipment installed at both prisons.” Spotlight subtitled its account “Wha, No Pics.?”39 Both Spotlight and Public Opinion identified the photographic medium as the vital counterpart to the fingerprint in the criminal investigation unit’s archives. The absence of a photograph was the “reason hunt was delayed.”40

Martin by late 1948 was, as the Public Opinion piece conveyed, “known to authorities.”41 What can be gleaned from institutional archives about his history comes largely from newspaper reports of Martin’s court appearances. He is legible precisely at moments when authorities censured him for infractions against the law. He appears in the newspaper archives as a petty criminal starting in 1938. For over a decade he stood accused of a range of crimes, from the theft of fabric from a dressmaker’s parlor to a “violent attack,” for which he was sentenced to prison.42 Two years into his term Martin escaped from the maximum security general penitentiary. Police tracked him to the Carib Hotel, where he engaged in a shoot-out with officers. He was able to escape, killing one police officer and a young woman, and wounding two others.43 Four days later Martin killed another man, and another narrowly escaped death. These incidents set off “the greatest and longest man-hunt in the modern annals of Jamaica.”44

Despite the initial delay in the pursuit of Martin, the authorities did publish a photograph of a man they identified as Martin on the front page of the Daily Gleaner on September 2, 1948, under the heading “Wanted for Murder.” The barely legible image discussed earlier (because of its history of mechanical and digital reproduction) of a figure with gun in hand appeared with the text: “Aged 29. Height, 5 feet, 3 inches; medium build; colour, black: eyes and hair black; several front teeth in upper jaw missing. When last seen was wearing trousers and a light brown check shirt. Will probably be found in possession of a revolver.” The police offered a reward of 200 pounds for information leading to the arrest of Martin.45

In the Daily Gleaner the following day “the latest and fuller description” of Martin was published, under the headline THIS IS THE KILLER. The written description noted a number of accessories that the fugitive might wear to disguise himself—shades, “Duke” heels, false or gold teeth— highlighting the unreliability of the very description from the day before.46 The addendum underscored a certain uncertainty surrounding Martin’s appearance, and the ways that the subject could seemingly slip in and out of many guises. A range of people could fit the shifting contours of Martin’s appearance.47

The outlaw sent letters to the press and the police, which further destabilized and reframed the emergent narrative about him. In a letter received by one Detective Sergeant Scott of the Halfway Tree police station, Martin made what might be described as counterclaims about the evidence presented about his encounters with the police in the papers.48 He called into question the facts known about him, right down to undermining the most fundamental thing the authorities and media thought they knew, his name. As the Daily Gleaner further reported several days later, “He said [in a letter] that his real name was not Ivanhoe Martin or Ivan Brown but Ivanhoe Blackwood.”49 The letter went on to name a number of detectives whom he intended to “get,” including Scott. Intriguingly, Martin used a letter to claim his status in history: “I have made a record in crime history.”50

It is, of course, not certain whether Martin did write the letters to the newspapers, because many people started to appear as the fugitive. As the Daily Gleaner suspected, some people pretended to be Martin: “Letters to members of the Criminal Investigation Department and the ‘Gleaner’ purported to be written by Ivanhoe Martin, were received again yesterday, but in all cases, it would appear they were written by cranks, or persons with personal grievances against the police force.”51 The police were inundated with supposed sightings of Martin. Many people became suspect and vulnerable in the police’s manhunt.52 The Daily Gleaner, for instance, described a “courageous barmaid” who knocked out a man whom she suspected of being Martin.53 The fugitive’s phantom status became reified through copies, emulators, and decoys who claimed his identity and through misidentifications. The ubiquity of the description of his many guises also inadvertently claimed many people.54 Whether posing as Martin or trying to catch him, the outlaw’s unorthodox actions seemed to inspire, to license, new forms of sociality and rebellious subaltern behaviors.

Martin began to disappear into a social body that claimed him, to appear as the public. The film scholar Prakash Younger makes the case that Martin at this stage achieved the status of “social bandit,” an outlaw “whose criminal activities function to defend or serve the interests of the local against the exploitative activities of the state and empire.”55 As a correspondent in Public Opinion, Clive Ingram, opined,

Martin’s success in evading the police is not wholly attributable to a lack of public knowledge of what he looks like. . . .

In breaking prison, in evading recapture for a long time, and in shooting his way to freedom through a police cordon when trapped; and then proceeding to wreak death upon those whom he thought to have been his betrayers; Martin did simply what his neighbours would like to do themselves.

In their thinking it is the Law personified by the police that oppresses them, and Rigin had outsmarted and out fought the law.56

Ingram suspected that Martin’s disappearance was attributable to the ways fellow citizens and neighbors saw themselves in Martin’s plight, his fugitivity as a bid for their freedom from oppression from the law.

Practicing for the Camera: Posing for the Future

I want to turn back from Martin’s letter writing to the photograph of him that was published in the Daily Gleaner on September 2, 1948. Oral histories, reiterated in The Harder They Come, suggest that Martin had images taken and sent them to the press. An article in Public Opinion, however, suggests another set of circumstances through which photographs of Martin came to light. The report states that an “amateur photographer,” who had previously taken photographs of Martin when he “happened onto a place where Martin was ‘practicing,’” was the source for the “snap-shot pictures the police have in their possession.”57 Martin swore revenge on him for taking the images to the authorities. The Public Opinion piece detailed that “Martin who prided himself on his skill as a marksman thought it a good idea to pose for some pictures. And so he did.”58 It may be that the photographer of the image, which was published in the Daily Gleaner, was the source of another representation of Martin published on October 11, 1948. In this image, another “poor” photograph of Martin, a man wearing a hat assumes a stance with bent knees and draws two guns. The metal surfaces of the guns and the frame of a bicycle are the most discernible parts of the image. This image may also have been one of the sources for the Cliff photograph.

Regardless of how the photographs came to be published in the newspapers, I want to linger on the description in Public Opinion, which stated that Martin was “practicing,” when the photographer happened upon him. That the verb is bracketed by quotation marks begs the question, if the images were indeed taken before the manhunt, whom did Martin imagine as the audience for such photographs? Was he practicing a pose, a ruud bwai posture, before he was (and in anticipation of being) a wanted man? Can we understand this as an example of the afrotrope waiting to take material form, as preiconic or prephotographic? Did the photograph create a visual space for him in history, “criminal history,” where there was none?

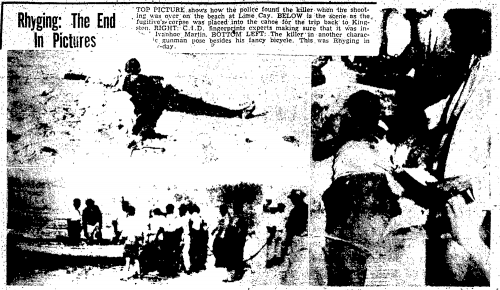

After six weeks, on October 9, 1948, the police did find Martin and killed him in a shoot-out on Lime Cay, south of Kingston.59 The Daily Gleaner, which assigned a special photographer to be imbedded with the police, published a photo essay subtitled “Rhyging: The End in Pictures.”60 As in many other images of Martin, the details are difficult to discern, but the captions offer some descriptive details. The series included three images of Martin’s corpse—splayed on the beach, in a canoe (ready for transport back to Kingston), and being fingerprinted. The latter image, the largest photograph, at the right, depicted Martin’s body quarantined to the left of the image and surrounded by fingerprint experts from the Crime Investigation Department. Given the history of Martin and his physical and photographic elusiveness, the photo showing the process of his fingerprinting may have served to reinsert him into the Rogue’s Gallery, along with the vital record of his fingerprints, to verify his physical capture through his capture in the police archives, and to reassert the authority of, the ontology of, photography. Contrary to the reports of Martin’s phantom-like appearances, the public circulation of photographs of his capture could confirm the “thereness” of Martin, his bodily presence and mortality using the skin, the surface of his finger, to confirm, to reassert, the authorities’ understanding of his identity. Even in death, the police and media sought to reinstate the repressive function and arresting work of the photograph.

The Jamaican poet Louise Bennett in a poem about Martin published in Public Opinion in 1948 calls attention to the police orchestration of the photograph and hints at the unintended interpretations of the image. The latter part of the poem reads:

Finga-print up him dead han! —-

But ah wanda wat hood happen

To de picture-man Miss Sue,

Ef wen him dah teck de picture

Rhygin duppy did sey “boo!”61

In Bennett’s imaginings, Rhygin’s ghost confronts the photographer and says “boo.” Bennett hints at how Martin’s reputation, his status as phantom, was likely enhanced and not diminished by the photographs of his body. The poem lays out a scenario, a conditional perfect “wat hood happen,” in which Martin continues to live and to have his phantom status, one that comes into being in relation to the photographer. Like the photographic afrotrope that waits, in Bennett’s poetic reimagining Martin will continue to take new forms in the future.

This history of Martin’s appearance and disappearance, his life and death as they intersected with photography, offers several snapshots of what the afrotrope is and can be in African diasporic contexts, especially when the afrotrope develops and travels through the medium of photography. First, the case of Ivanhoe Martin and the many instances of the disappearance of his photographic image—whether in the colonial criminal investigation archives or those of the Daily Gleaner—demonstrate how despite social, political, and institutional processes and public uses that might secret away certain photographs and histories, the afrotrope can emerge and indeed can proliferate in and across African diasporic contexts through the photographic medium. The history of Martin’s image suggests, too, how even the absence or disappearance of certain forms of photographic images can take material forms that are generative, productive, and affective. The image foregrounds as well how the materiality of disappearance—that which will remain visibly lost to recovery—is equally intrinsic to the functioning of the afrotropic.

Second, this history of Martin highlights a form of photography that is as much about notions of fugitivity as it is about photographic capture, fugitivity being an intrinsic part of the afrotrope’s photographic iterations. The history of Martin’s image is bound to the notion of fleeting forms of photographic and visual arrest. My archival consideration of Martin does not aim to posit a corrective to popular, filmic, or artistic understandings of his story. Rather, it seeks to draw attention to the narratives that developed about Martin, to linger on the precise elements of the history that are so often told and re-created, and what they reveal about understandings of photography in Jamaica. Martin is able initially to exceed or seek flight from the purpose of photographic archives of the colonial state, to undermine the ontology of the photograph as evidence or visual truth. Efforts to read photographs of him, his surface appearance, prove unreliable, uncertain. This afrotrope tells other shadow histories of photography by highlighting a photographic fugitivity, narratives about the medium’s inability to arrest African diasporic subjects, literally and figuratively. Martin’s “poor” photographic image would also become visually fugitive over time.

The emphasis in the newspaper accounts of Martin as able to shed his skin, to shirk ideas about his surface appearance, suggests that his story may be related to understandings of blackness more generally as readable on the surface of the body, and point to the intertwined ontologies of photography and blackness that rely on reading deeper meanings onto surface traits. Martin’s story, then, is about seeking flight from the forms of social arrest that produce blackness and criminality as located on the surface of the body. The afrotrope in this instance seeks to disrupt and disarticulate such framings of blackness, such understandings of the color black and subjects of African descent as having a common being—like the relation between a finger and fingerprint.

Finally, the history of Martin’s image represents, imprints, visualizes a communally authored representation, which was in the making for over half a century. The image of Cliff is not simply a reenactment of the image of Martin, but an image that took form through oral histories about the figure, through shared communal truths and aspirations passed down through generations, and in the gaps, the illegible and unknowable remains, of the story and the photographic traces of Martin.

Krista Thompson is the Weinberg College Board of Visitors Professor in the department of art history at Northwestern University. She is the author of An Eye for the Tropics (2006) and Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice (2015), which received the 2016 Charles Rufus Morey Book Award from CAA. Thompson is currently working on The Evidence of Things Not Photographed, a book that examines notions of photographic disappearance in colonial and postcolonial Jamaica, and “Black Light,” a manuscript about the light artist Tom Lloyd and archival recovery in African American art.

From Art Journal 77, no. 2 (Summer 2018)

- Albert Chong, “The Photograph as a Receptacle of Memory,” Small Axe 13, no. 2 (June 2009): 130–31. ↩

- Chong uses the term “receptacle” to refer to the form and work of photography in the Caribbean, viewing the medium literally as a holder of spirits and holder of shared time between distant generations. I suggest, building on Chong, that the trope of Ivanhoe Martin assumes the role of receptacle, connecting different times, as well as serving as an ever-shifting contour that takes shape through different media and is populated by changing meanings and material manifestations of photography. ↩

- This essay is part of a series in Art Journal on the afrotrope, edited by Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson. For more on the afrotrope, see Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson, “Afrotropes: A User’s Guide,” Art Journal 76, no. 3–4 (Fall–Winter 2017): 7–9; and Leah Dickerman, David Joselit, and Mignon Dunn, “Afrotropes: A Conversation with Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson,” October 162 (Fall 2017): 3–18. For an earlier essay that started to lay out the conceptual frame of the afrotrope, see Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson, “Perpetual Returns: New World Slavery and the Matter of the Visual,” Representations 113 (Winter 2011): 1–15. ↩

- André Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” trans. Hugh Gray, Film Quarterly 13, no. 4 (Summer 1960): 8. People across diasporic communities have navigated being viewed, as with photographs, as objects on which meaning lies on the surface, on the surface of their skins. ↩

- I am reproducing the rhetoric published almost verbatim in the early press surrounding the film. Bev Braune, “‘You can get it if you really want’: Viewing The Harder They Come Again and Again after a 1977 Interview with Director Perry Henzell,” Wasafiri 13, no. 26 (1997): 31–36. Martin, for instance, was described as a “fugitive” in “‘Rhyging,'” Daily Gleaner (Kingston, Jamaica), October 8, 1948, 8; as a “phantom killer” and “escaped convict” in “Wife Sees Husband Shot at Dawn, the Killer’s Third Victim,” Daily Gleaner, September 4, 1948, 1. Prakash Younger uses the term “social bandit” in Younger, “Historical Experience in The Harder They Come,” Social Text 23, no. 1 (1982): 43–63. Rachel Moseley-Wood describes the representation of Martin in The Harder They Come as a “complex portrait of a tragic, would-be folk hero.” Moseley-Wood, “‘Badda Dan Dead’: Notoreity and Resistance in The Harder They Come,” Wadabagei 12, no. 2 (Spring 2009): 83. ↩

- Jacques Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” trans. Eric Prenowitz, Diacritics 25, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 9–63. ↩

- “Shadow histories” is influenced by Kevin Young’s conceptualization of the “shadow book” in Young, The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2012), 10–19. ↩

- Throughout the essay I use “Martin” to refer to the historic (and now mythical) figure who rose to notoriety in the late 1940s. ↩

- The cinematographers for the film were Frank St. Juste, David McDonald, and Peter Jessop. They likely staged the photograph and scene. See Kevin Kelly, “‘Harder They Come’: Study in Criminal Courage,” Boston Globe, April 26, 1973. ↩

- See Steven Kovács, “Review: The Harder They Come,” Cinéaste 6, no. 2 (1974): 46–47. ↩

- Anne Anlin Cheng’s discussion of “second skins” and the photographs of Josephine Baker are comparable here. Cheng, “The Women with the Golden Skin,” Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2011): 101–31. ↩

- The concept of the ruud bwai has multiple historically specific meanings. In immediate post-independence Jamaican cultural politics, ruud bwai referred to an outlaw turned folk hero, whose defiance, aggressiveness, and fearlessness seemed to embody and personify the revolutionary-liberatory postures being assumed across anticolonial and nationalist movements in many parts of the world. As David Scott succinctly describes it, the ruud bwai in Jamaica in the 1970s was “at once a figure of intense fascination and mortal dread, or urban folk-heroization and draconian police operations, at once an emblematic Fanonian figure of internalized violence and rituals of embodied resistance, and the incarnation of a desperate, even pathological, criminality and lawlessness.” Scott, Refashioning Futures (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), 209. ↩

- Henzell quoted in Stefan Krause, “An Afternoon with Perry Henzell,” Rasta Studio, 2002, at http://rastastudio.com/Perry/perry.txt, as of May 1, 2018. ↩

- “Wife Sees Husband Shot at Dawn,” 1. ↩

- Ibid. Martin is described as “drawing back into the shadows” in another section of the article. See section of “Wife Sees Husband Shot at Dawn” subtitled “Hunt for Martin Enters Fourth Day.” ↩

- See “Reward Out for Killer,” Daily Gleaner, September 5, 1948, 1. ↩

- “Bloodstained Clothing May Be ‘Rigin’ Clue,” Public Opinion Special Reporter (Kingston, Jamaica), September 11, 1948, 1. ↩

- For details of the numerous sightings of Martin and the frantic police efforts to apprehend him, which include accounts of him “vanishing,” “slipping away” and “reappearing,” see “Reward Out for Killer,” 1; “Underworld Shelters Rhyging,” Daily Gleaner, September 8, 1948, 1; “Hunts Bay Corpse Sparks ‘Rhyging’ Rumour: Not the Killer Fingerprints Show,” Daily Gleaner, September 16, 1948, 1; and “Alias Rhigin,” Spotlight magazine, September 1948, 24. The phrase “the notorious desperado disappeared” occurs in “‘Rhyging’ Killed by Police,” Daily Gleaner, October 10, 1948, 1. ↩

- See Richard Dyer, Stars (London: British Film Institute, 1979). ↩

- “Alias Rhigin,” 24. ↩

- See Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (Winter 1986): 7; John Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1993); and Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017). ↩

- Ibid., 16 and 7. ↩

- I am using Kaja Silverman’s description of photography here. Silverman, “From the Ideal-Ego to the Active Gift of Love,” in The Threshold of the Visible World (New York: Routledge, 1996), 39. “Drew back into the shadow of the car” comes from “Wife Sees Husband Shot at Dawn,” 1. ↩

- “Big Turnout at Screening of ‘The Harder They Come,'” Boxoffice, March 12, 1973, C30. ↩

- Indeed the critic Kenneth Harris argues that the film was created precisely to sell a new product of Jamaican musical culture to white audiences. Harris, “Sex, Race Commodity and Film Fetishism in The Harder They Come,” in Ex-Iles: Essays on Caribbean Cinema, ed. Mbye B. Cham (Trenton: Africa World Press, 1992), 212. ↩

- See William Lyne, “No Accident: From Black Power to Black Box Office,” African American Review 34, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 39. ↩

- Jimmy Cliff’s lyric “Well the oppressors are trying to keep me down; trying to drive me underground. And they think that they have got the battle won; I say forgive them Lord they know not what they’ve done,” from the song “The Harder They Come,” appears on the poster for Huey Newton. On the back of the poster appears an inscription acknowledging Cliff. A union printing label (s565) is printed in black ink at bottom center stating “Copyright—Jimmy Cliff, The Harder They Come (Ackee Records, Inc.” in white at the right near the center. ↩

- For some of the literature on notions of fugitivity as they relate to visual representation, see Huey Copeland, “Glenn Ligon and Other Runaway Subjects,” Representations 113, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 73–110; Michael A. Chaney, Fugitive Vision: Slave Image and Black Identity in Antebellum Narrative (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2009); and Sarah Blackwood, “Fugitive Obscura: Runaway Slave Portraiture and Early Photographic Technology,” American Literature 81. no. 1 (2009): 93–125. On fugitivity more generally, see Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Wivenhoe, UK; New York; Port Watson. NY: Minor Compositions, 2013); and Stephen Best and Saidya Hartman, “Fugitive Justice,” Representations 91, no. 1 (Fall 2005): 1–15. ↩

- Rachel Moseley-Wood’s work is an exception here. She questions the plausibility of Martin’s ability to take and send the photograph to the papers. Moseley-Wood, “‘Badda Dan Dead,'” 80–102, 142. ↩

- Poor images, as Steyerl elaborates, are those in which the “quality is bad, its resolution substandard. As it accelerates, it deteriorates. It is a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution. Hito Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image,” e-flux 10 (November 2009): 32. ↩

- See Copeland and Thompson, “Perpetual Returns.” ↩

- See Steyerl, 41. ↩

- As Steyerl explains, “Poor images are poor because they are not assigned any value within the class society of images—their status as illicit or degraded grants them exemption from its criteria. Their lack of resolution attest to their appropriation and displacement.” Steyerl, 32. ↩

- This sense of the unknown and uncoverable is reminiscent of what Kevin Young describes when he characterizes some books in the African American literary tradition as “incomplete, defaced, half-erased,” noting how such removals and gaps highlight what is beyond our knowing, and “suggest that all knowing is somehow involved in knowing just that.” Young, The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2012), 12–13. ↩

- Achille Mbembe, “The Power of the Archive and Its Limits,” in Refiguring the Archive, ed. Carolyn Hamilton, Verne Harris, Michele Pickover, Graeme Reid, Razia Saleh, and Jane Taylor (New York: Springer, 2002), 24. ↩

- Marilyn Ivy, Discourses of the Vanishing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 22. ↩

- “Bloodstained Clothing May Be ‘Rigin’ Clue,” 1. ↩

- “2-Gun Killer Dares Police,” Daily Gleaner, September 3, 1948, 1. ↩

- “Alias Rhigin,” 4. ↩

- “Bloodstained Clothing May Be ‘Rigin’ Clue, 1. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- That he would be accused of stealing fabric would presage his later reputation for being a “neat dresser,” as suggested both in “wanted” ads and in the fashioning of his image in the photograph of Cliff. “Criminal Trial Adjourned to Get a Witness,” Daily Gleaner, July 30, 1946, 3. ↩

- Martin killed one police officer, Detective Corporal Edgar Lewis, and a young woman, Icilda Tibby Young, girlfriend of Eric “Mosspan” Goldson, someone Martin thought had informed on him. “Wife Sees Husband Shot at Dawn,” 1. ↩

- “‘Rhyging’ Killed by Police,” 1. ↩

- Police notice, Daily Gleaner, September 4, 1948, 18. ↩

- The full description, from “Reward Out for Killer,” 1:

THIS IS THE KILLER

If you see this man, get to the nearest phone and call the police.

This is the latest and fuller description of ‘Killer’ Martin: Age 29, height 5 ft. 3 inches (may be wearing shoes with high heels—’Duke’ heels (as) they are known in Kingston’s west-end underground—making him 5 ft. 5 inches), medium build, colour black, hair and eyes black, several front teeth missing from upper jaw, but may be wearing false teeth with all plain or with one or two teeth of gold. Often wears sun glasses—polarized sun glasses with a narrow bridge. Has a habit of looking backward every few steps when walking, and spitting after a few words he speaks.

Approach with caution. He is dangerous. He is armed. ↩ - Revealingly, across newspaper reports Martin’s nickname had many variations, perhaps stemming from efforts to phonetically render his nickname. Sometimes multiple misspellings appear in the same text. Rigin’ and Rhigin’, for instance, are reproduced in “Bloodstained Clothing May Be ‘Rigin’ Clue,” 1. ↩

- Martin letter quoted in “2-Gun Killer Dares Police,” 1. ↩

- “Is ‘Rhyging’ Martin or Blackwood?” Daily Gleaner, September 9, 1948, 1. ↩

- Martin letter quoted in “2-Gun Killer Dares Police,” 1. ↩

- “Is ‘Rhyging’ Martin or Blackwood?” 1. ↩

- “Early Tuesday morning reports had him in Cockburn Pen. Late Tuesday afternoon reports had him in the Mannings Hill sector of St. Andrew, riding a nickel-plated bicycle. Late Tuesday (illegible text) had him in Wellington Street, Denham Town.” “2-Gun Killer Dares Police,” 1. See “Reward Out for Killer”; “Underworld Shelters Rhyging,” 1; and “Hunt’s Bay Corpse Sparks ‘Rhyging’ Rumour.” ↩

- “A courageous barmaid in Western Kingston made a bid to turn in the wanted desperado Ivanhoe (Rhyging) Martin on Monday night and would have—had she not knocked out the wrong man.” “No, Not ‘Rhyging,'” Daily Gleaner, September 8, 1948, 1. ↩

- This scenario recalls the use of photography in the FBI hunt for Angela Davis in 1970. Davis later recalled how photographs structured “people’s opinions about me as a ‘fugitive’ and a political prisoner. . . . Hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of Afro-wearing black women were accosted, harassed, and arrested by police, FBI, and immigration agents during the two months I spent underground. One woman who told me that she hoped to serve as a ‘decoy’ because of her light skin and big natural, was obviously conscious of the way the photographs—circulating within a highly charged racialized context—constructed generic representations of young black women.” Angela Davis, “Afro Images: Politics, Fashion, and Nostalgia,” in Picturing Us, ed. Deborah Willis (New York: New Press, 1994), 176. ↩

- Eric Hobsbawn’s definition of the “social bandit” informs Younger’s characterization of Martin. See Younger, 49. ↩

- Clive Ingram, “‘Rigin,'” Public Opinion, September 11, 1948. ↩

- “I understand that Martin now has this lad (the photographer) on his list of persons with whom he wants to get even,” “Bloodstained Clothing May Be ‘Rigin’ Clue, 1. Moseley-Wood notes too that “buried in a long story after he was shot, reference is made to a photographer who, having supplied the police with Rhygin’s picture, was breathing a sigh of relief at his death.” She cites the Daily Gleaner, October 11, 1948. Rachel Moseley-Wood, “‘Badda Dan Dead,'” 83. ↩

- “Bloodstained Clothing May Be ‘Rigin’ Clue,” 1. ↩

- “‘Rhyging’ Killed by Police,” 1. ↩

- “Rhyging: The End in Pictures,” Daily Gleaner, October 10, 1948, 1. ↩

- Louise Bennett, “Dead Man,” Public Opinion, October 16, 1948, 8. A translation, which does not quite capture the conditional perfect tense of the poem, might read:

Finger-print his (Martin’s) dead hand! —-

But I wonder what would happen

To the photographer Miss Sue

If when he took the picture

Rhygin’s duppy (ghost/spirit) said “boo!” ↩