I grow old as the world does,

waiting to be lost in the bottomless pit

of silent and deserted divinity,

sharing in the light of angelic intelligences

—Umberto Eco

The Name of the Rose (1980)

The notion of the desertion of the divine is one that affects much religious art in the space of the museum. Previously functioning spaces and ritual objects struggle to assert their former powers of conjuring the sacred once they are inserted to serve other narratives in art museums. Medieval art, like so many other cultural traditions based in ritual, primarily had to be successful in the spiritual work that it was commissioned to aid. In the museum of today viewers experience objects that have ceased to be useful, yet as museum practitioners we often strive to channel and activate some of that “deserted divinity” through language, lighting, and ambiance.

The Met Cloisters is a rare paradox as a museum: it was designed between 1925 and 1938 to present medieval architecture as object, and did so by rebuilding medieval fragments loosely based on the plan of a medieval monastery. The overall effect is somewhere in between museum and monastery, as vividly described by the acerbic critic Louis Mumford:

At a distance the Cloisters looks not like the excellent museum that it is but like a transplanted building, picked up by the jinn and whisked through the sky—not so much an honest relic as a wish. . . . Indeed, the very virtue of this structure, its fidelity to history, only accentuates one’s feeling of being bewitched. For whereas fake Gothic like that of the Riverside Church is plainly a fake at any distance, cast in one piece, built at the same time, this new building is full of authentic disharmonies.1

The “authentic disharmonies” of Mumford’s Cloisters, “not so much an honest relic as a wish,” are brought into productive tension through the animation of its most recent exhibition, Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination. In this exhibition, purposeful anachronisms of period rooms and modern costumery join to create cohesive desires, unmoored from historical boundedness. This exhibition is curated by Andrew Bolton and installed throughout the Met Cloisters, in the Medieval Galleries, the Robert Lehman Wing, and the Costume Institute at the Met Fifth Avenue. This essay focuses on the installation at the Cloisters for a few reasons: because I have been a lecturer there for over a decade, and thus am intimately familiar with the space; because of the unity of the Cloisters’ installation; and, finally, due to the museological issues raised specifically by its status as a series of interconnected period rooms.2

The architect of the Cloisters, Charles Collens, also designed Riverside Church. Mumford appreciates the honesty of The Cloisters’ structure, because it is not an imitation of a specific medieval prototype; rather, it endeavors to retain the proportions and spatial attitude of the original edifices. As Collens wrote:

I feel to get the best result in a museum of this sort the visitor should be introduced to an atmosphere in which all the rooms are carried out in the period of architecture characteristic of the exhibits,….to make it possible for the visitor to pass through a series of rooms, starting with Romanesque, going through Early Gothic, then into Late Gothic, in which all the details, ceilings, the fenestration, and the other features are carried out in strict archaeology so that the entire atmosphere is without any disturbing feature….I also think that the building should be self-enclosed, that the rooms should be not too large in size, and that the whole plan and atmosphere should be of a most intimate character.3

Because most of the original architectural elements at the Cloisters are Romanesque rather than Gothic—a style of architecture that has lower, smaller, and more sculptural spaces—the entire museum imparts a kind of closeness, which is essential to the success of Heavenly Bodies.4

First, a word about the medieval cloister itself: it is the architectural and spiritual nucleus of a monastery. It connects the disparate rooms of the monastic precinct through a covered walkway with a central garden that is open to the sky. It is also the place where monks come to meditate on, memorize, and recite out loud sacred scripture. At the Cloisters, the fragments from the twelfth-century Benedictine monastery of St. Michel de Cuxa have been rebuilt in the center of the museum using stone from the same quarry that the medieval sculptors employed. To an untrained eye, it is difficult to differentiate the twentieth-century elements from the twelfth-century stones, and the Cuxa cloister functions architecturally in the museum the way it would have in the monastery: as an organizational device connecting the various galleries of the museum. Even though it is only a quarter of the size that it would have been in the twelfth century, a visitor encounters the architectural space as it was intended to be experienced. In this way, the arrangement and presentation of the collection at the Cloisters is inevitably bound to the simulation of a medieval universe, even if it stops just short of recreating that world.

In the decades since The Cloisters opened in 1938, the Met has theorized the Cuxa cloister as a “period room” featured in the same volume as the more familiar French period rooms in the Wrightsman Galleries at the Met Fifth Avenue. In the foreword to this reevaluation of period rooms at the Met, then-director Phillippe de Montebello wrote, “Visitors to the Cuxa cloister invariably lower their voices as if they feel the presence of monks making their way to vespers, and the Astor court is as much a retreat for the harried New Yorker as its inspiration was for the Chinese scholar who first built it.”5 Whether or not Montebello’s observation is verifiable, there is something about inhabiting formerly sacred spaces at the Cloisters, even temporarily, that adjusts our attitude and behavior. In his classic study, The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard observes how once a space is lived in, it becomes organic and loses its cold rectilinearity; “inhabited space transcends geometrical space.”6 In other words, spaces occupied by people acquire a kind of humanity of their own, and this effect is part of the transformation of the Cloisters through Heavenly Bodies.

Each gallery at the museum is populated with dressed mannequins that relate to the collection thematically, formally, or performatively. The mannequins were manufactured specifically for the exhibition; Bolton went back and forth with the sculptor multiple times to ensure that their expression bore a sense of reverence. Initially Bolton’s idea was to duplicate the face of the Virgin Mary in Michelangelo’s Pietà (1498–1499), which proved difficult; yet the overall demeanor of Michelangelo’s Virgin is preserved.7 Both the male and female mannequins have their eyes closed, their chins tilted slightly upward, and stand on their tiptoes: the effect is one of an active repose, alert and humble, deferential and quietly assertive, as if responding to the palpable presence of the divine in the now-defunct apse, cloister, chapel, and chapterhouse.

The comportment of the mannequins is essential to convincingly convey that they are in ongoing dialogue with the spaces they inhabit. It is almost perilous to introduce life (apart from viewers) into a museum environment, because it runs the risk of invoking an ethnographic attitude, further distancing an already alien and remote past (the Middle Ages) from the public.8 I am of course referencing the diorama, an imagined or invented “window” into other worlds that masquerades as reality. This installation is successful in avoiding such pitfalls in part because of the consistent denial of engagement with the viewer through the mannequins’ closed eyes. These actors are frequently addressing or engaged with an absence; the vignette is always left slightly incomplete so that the narrative is partial, suggesting a moment plucked from a larger story rather than a linear timeline.9

In some ways, the introduction of characters that engage with the sacrality of these spaces returns us to an earlier era in the museum’s history. The American sculptor George Grey Barnard (1863–1938) amassed the core collection of the Cloisters’ architectural and sculptural fragments; Barnard is largely forgotten today, but trained with Auguste Rodin and was highly regarded in his time. Like Rodin, Barnard was impressed with the skill of medieval sculptors at a time when the Middle Ages were still considered to be primitive.10 While at work in France on a commission for the Pennsylvania State Capitol building in Harrisburg, his funding ran out, and so he became an art dealer. He traded primarily in Romanesque and Gothic architectural fragments, which were available for acquisition, since their original edifices had been either destroyed or abandoned during the French Revolution. This was a great period for collecting European art in America, the age of J. Pierpont Morgan and Isabella Stewart Gardner, and Barnard’s intention was to sell his entire collection to a wealthy patron once it was shipped over from France in 1913.11 Unsuccessful at securing a buyer, Barnard decided to open his own museum: Barnard’s Cloisters Museum at the northern tip of Manhattan, not far from where the museum is today. This was a major popular success: at the time, most New Yorkers had never been exposed to actual medieval art on this scale.12

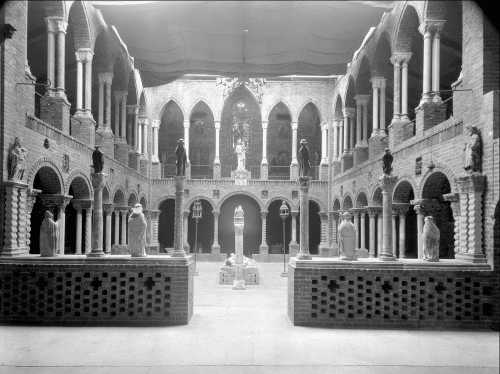

Barnard wanted to recreate the entire atmosphere of the Middle Ages, so his museum took the form of a basilica—the central longitudinal space functioning as the nave with subsidiary aisles on either side.

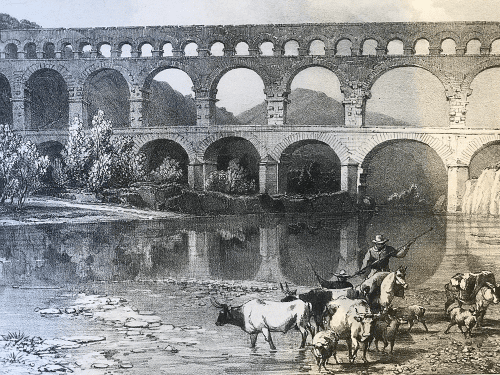

The walls were artificially aged, the space lit by candles, and the guards dressed as monks.13 Barnard harnessed many of the underlying misconceptions of the imaginary Middle Ages perpetuated by fin-de-siècle medievalism, like darkness and superstition that held preindustrial primitives in the grip of piety. The sculptor’s ideas about the Middle Ages sprang directly from the romanticized vision of medieval monuments depicted in the Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’ancienne France (1820–1878), a series of lithographs of monuments in heightened stages of ruin and disrepair produced after the destruction of the Revolution.14

These lithographs conflate medieval and modern time through their vignettes of actors engaged in a variety of activities. In some, local townsfolk appear oblivious to the ancient ruins, and in others, single figures of aristocratic origin are absorbed in acts of piety.15 When I first saw the installation of a bride at the threshold to the apse of the Romanesque church of St. Martin from Fuentidueña, I was immediately transported to an image from the Voyages of a medieval woman standing at a threshold in a different place: the narthex of the Romanesque abbey of Moissac in Languedoc, France.

Dressed in a form-revealing gown tightly cinched by a long belt at the waist, she stands turned away from us, hands clasped around a rosary, looking out of the open door to the porch beyond.16 What is the role of this woman in this series? The simple reason is to give us a sense of scale (exaggerated, in this case), but more importantly, her presence lends a veneer of authenticity to the rendering, which satisfies the viewer’s imagination as to what this structure might have felt like in the Middle Ages.

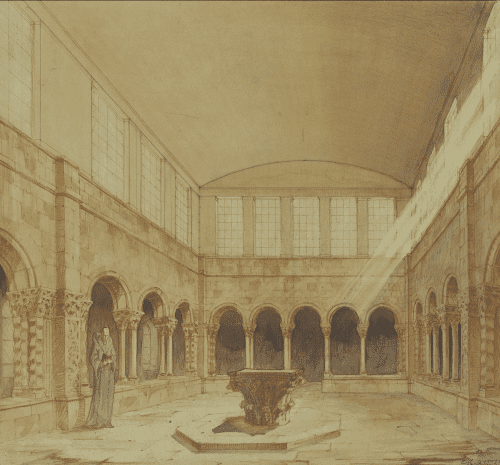

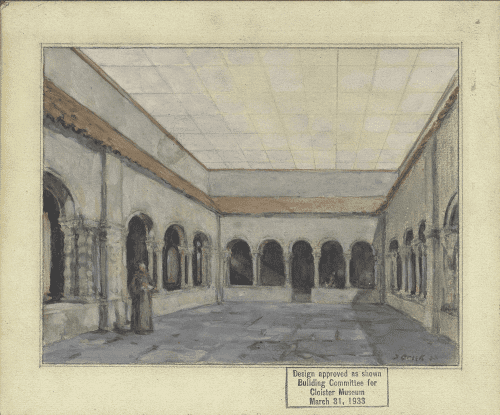

This desire to return the monument/object to an imagined authenticity also motivated Barnard’s museum and continued to inform the design for The Cloisters after John D. Rockefeller, Jr. provided funds to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to acquire Barnard’s entire collection. Charles Collens was hired to design the new structure, and together with Joseph Breck, the Met’s curator of decorative arts, they devised the galleries of the museum, which opened in 1938.17 There exists a wealth of correspondence between Breck, Collens, and Rockfeller regarding design decisions, which allows us to map the evolution of The Cloisters’ ethos. For example, both Breck and Collens proposed designs for the gallery that was to enclose the reconstructed cloister from St. Guilhem-le-désert in 1933. Breck’s rendering shows a modern skylight, which would let natural light into a closed gallery to approximate the open-air arrangement of the original garden. Collens’s solution was to insert a clerestory of windows on all four sides. Breck’s solution, which was cleaner, was accepted on March 31, 1933.

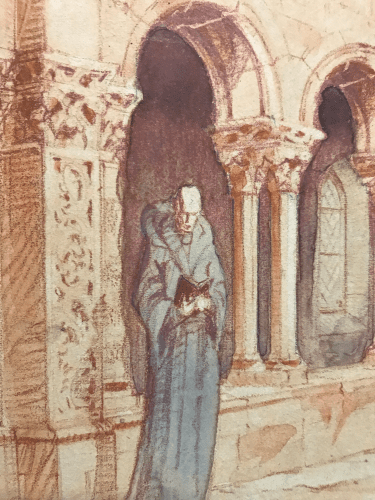

However, both Breck’s and Collens’s mockups included a medieval monk in the space rather than a contemporary visitor, betraying that innate yearning for authenticity, the desire to be in tangible communication with medieval users and makers. In Collens’s rendering, the monk holds a book in both hands and his mouth is open, either in song or because he is reading out loud, an act that is entirely commensurate with the activities conducted in a medieval cloister.18 Breck’s watercolor also includes a tonsured monk in a brown habit, but his is more summarily rendered, so we can only discern that his hands are clasped in front of him, perhaps in a gesture of prayer. These monks were fantasies, much like the woman in the Moissac lithograph produced precisely a century before these proposals, and they never made it into the final arrangement when the museum opened to the public in 1938.

Yet, in Heavenly Bodies, “monks” populate the cloister, as part of the display, as never before. The two ensembles in the St. Guilhem cloister, both by Valentino (Fall/Winter 2015–2016), are elevated by way of mounts that suspend them in the second story of the cloister; both wear cashmere capes that recall the black habits of Benedictine monks, who would have occupied the cloister in the medieval period. Again, out of reach, viewers are denied engagement with these “heavenly bodies,” which enables us to step back and consider actor and architecture in active dialogue with one another. As Alexander Potts has shrewdly observed, we are less likely to appreciate scale with our own bodies than when we witness its effect on other bodies. Because we observe this interaction between actor and object from a distance, “the viewer is simultaneously drawn inside and made to feel displaced.”19

Indeed, the St. Guilhem cloister is anthropomorphized through this engagement, and comes to life as our eyes dart back and forth between the tiered arcades of the cape and the rhythmic repetition of arches in the cloister. Valentino was inspired by the stacked stories of round arches of the Colosseum in Rome, just as Romanesque sculptors appropriated the forms of Roman monuments that populate western and southern France, such as the Pont-du-Gard in Nîmes.20 Through such parallels we can understand appropriation as a reanimation of the past filtered through the concerns of the present, which is a strategy that transcends place and time.

The most convincing and illuminating of the vignettes are those that engage with the collection beyond one-to-one parallels with famous works of medieval art repeated on the clothing. These transcriptions, like the dresses by Jun Takahashi dispersed in the “Garden of Eden” runway, are gorgeous but gratuitous, as are Alexander McQueen’s ensembles in the Late Gothic gallery.

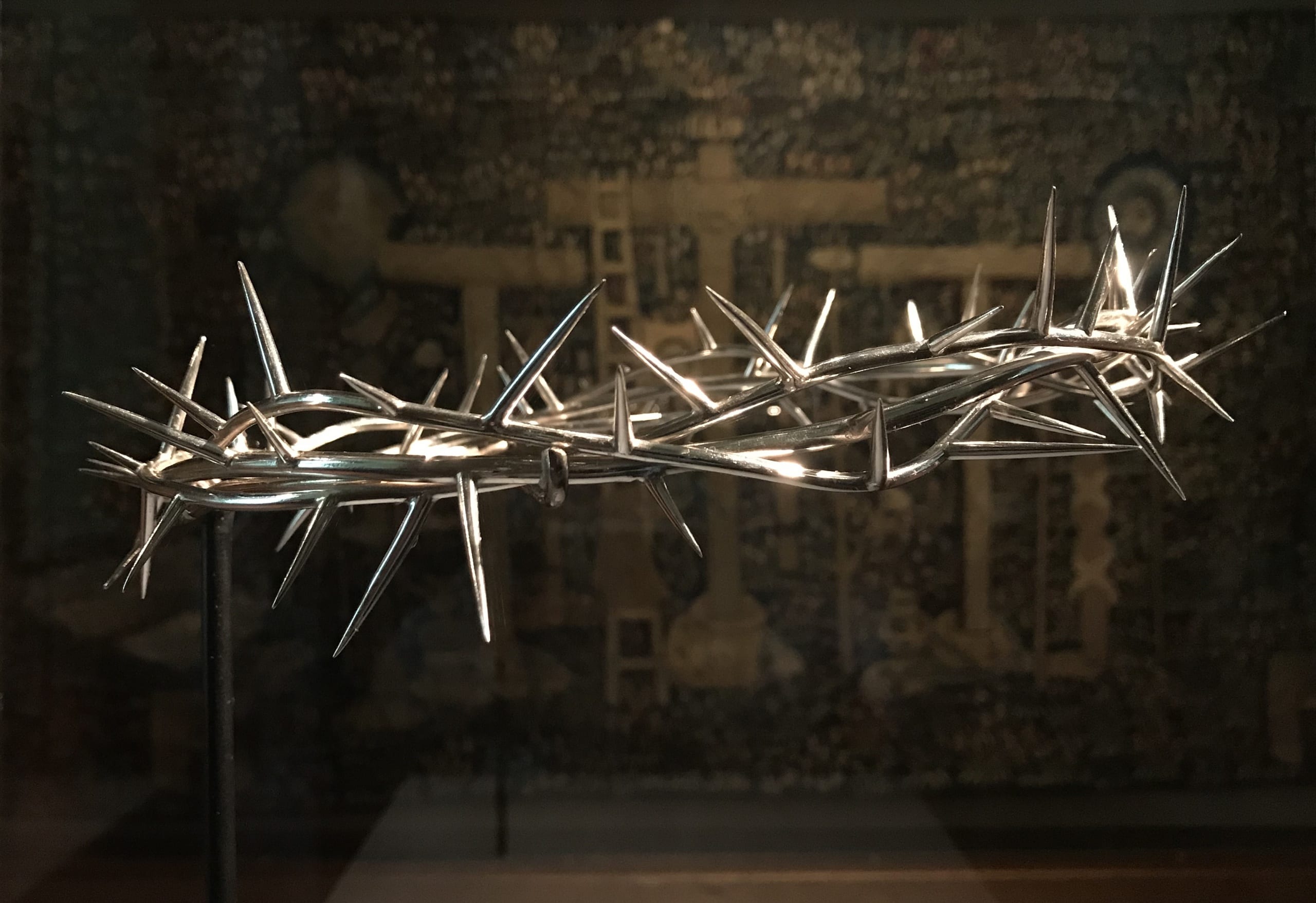

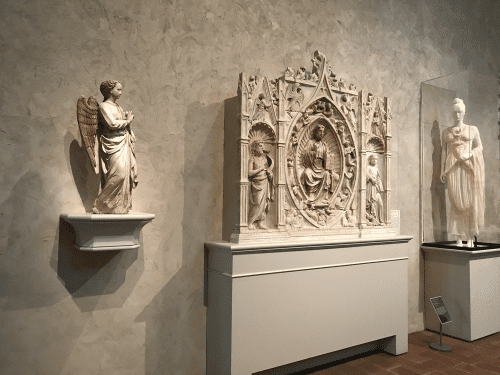

Rather, McQueen’s radical sartorial appropriation of Catholic iconography is again best appreciated through fragmentation and absence: at the entrance to the Cloisters’ Treasury, suspended at head height, is McQueen’s silver “Crown of Thorns Headpiece” (Autumn/Winter 1996–1997). It hovers in front of a sumptuous tapestry depicting the Crucifixion scene, which is missing Christ; both the medieval and modern await the return of the divine, and through this dialogue they partially complete one another. This object is one of the most arresting in Heavenly Bodies because of its deep connection to the cult of relics that affected nearly every aspect of medieval culture. A relic is organic matter: a piece of bone, a hair, an arm, of a saint; in and of themselves, relics are humble and perishable reminders of the transience of humanity. They need reliquaries, with all their gold, silver, and jewels, to convey the spiritual potency of the saint. McQueen’s “headpiece” has conflated relic and reliquary, with the precious material taking on the form of the relic to become one and the same. This is a cunning curatorial choice because the Treasury is filled with reliquaries and other cherished objects, including chalices used in the celebration of the Eucharist, which await the viewer in the adjacent gallery. 21 Another more incisive, subtle, and playful insertion is of a gossamer light pink dress by John Galliano (Spring/Summer 1986), to the right of a carved marble altarpiece by Andrea da Giona (1434). This seemingly weightless ensemble becomes an avatar for the missing Virgin Mary, and completes the Annunciation by engaging with the Angel Gabriel on the other side of the altar.

When the players fully inhabit these medieval and modern spaces, they move beyond mere juxtaposition and become interpretive glosses. In so doing, they exemplify the observation by the cultural theorist Bill Brown that “inanimate objects organize the temporality of the animate world.”22 At the Cloisters, many of the architectural spaces themselves are on permanent display, and have been reactivated through this exhibition. Inanimate actors divert and focus our attention to aspects of the artworks that we may have muted or forgotten, as we have become accustomed to a largely unchanging installation—one that has come to represent itself, as period rooms do. The modern and contemporary costumes and the medieval objects at the Cloisters are engaged in a kind of chemical reaction, one that leaves them both changed for the better. The divinity that once infused these spaces through prayer, song, and chant will never return, but for now, the spaces are no longer deserted, and have acquired a renewed resonance through Bolton’s “angelic intelligences.”23

Risham Majeed joined the department of art history at Ithaca College in 2015 after completing her PhD at Columbia University. At Ithaca College, Majeed teaches courses on the history of museums and exhibitions, African art, and medieval art. This Spring she organized an interdisciplinary symposium, “Primitivism before/beyond Modernism,” which considered primitivism as a trans-historical strategy of self-definition. In Fall 2018, Majeed will teach an Exhibition Seminar that will mount an exhibition on the theme of “African Art and Authenticity” in Spring 2019 at the college’s Handwerker Gallery. This will be another collaboration with Cornell University’s Herbert F. Johnson Museum, and will feature additional loan objects from NYC collections. Her research on Meyer Schapiro is forthcoming in RES: anthropology and aesthetics, as an article entitled “Against Primitivism: Meyer Schapiro’s Early Writings on African and Medieval Art.” Her current book project chronicles the parallel treatment of medieval and African art as “primitive” in the museums of the Trocadéro palace in Paris (1878–1937), and is entitled Primitive before Primitivism: Medieval and African Art in the 19th Century. Majeed is a member of CAA’s Museum Committee and has been a lecturer at the Met Cloisters since 2006.

- Lewis Mumford, “Pax in Urbe,” in Robert Wojtowicz, ed., Sidewalk Critic: Lewis Mumford’s Writings on New York (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998), 213. ↩

- In a forthcoming essay, I contextualize the exhibition for medievalists, paying special attention to the parallels between the contemporary installations and the concerns of the Middle Ages. See “Excess and Austerity: Benedictines Rule at the Cloisters,” International Center of Medieval Art (ICMA) Newsletter (July 15, 2018). ↩

- Charles Collens quoted in Timothy Husband, “Creating the Cloisters,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Spring 2013), 33. Husband gives the most up-to-date early history of the museum. ↩

- Curator Joseph Breck wrote, “A museum of the type of The Cloisters offers to its visitors an intimacy which is particularly favorable for the appreciation of any popular art such as that of the Middle Ages. We must stand our distance when we admire the splendor of Louis XIV, but the homely art of the cathedral builders we want to take to our hearts,” in “The First Year at the Cloisters,” MMA Bulletin 22 (1927), 158. ↩

- Phillippe de Montebello, “Foreword,” in Amelia Peck, et al., Period Rooms at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996). ↩

- Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1958), vii. ↩

- Conversation with Andrew Bolton at the Met Cloisters, May 31, 2018. The mannequins were custom-made by the company Proportion. See also Laird Borelli-Persson, “Among the Heavenly Bodies on Display at the Costume Institute’s Upcoming Show Will Be Custom-Made Mannequins,” Vogue, May 4, 2018, at https://www.vogue.com/article/met-gala-custom-mannequins, as of July 16, 2018. Each mannequin also has a custom-designed wig made by Shay Ashual; the styles vary from the evocation of a demure monastic tonsure to fire-red dramatic crops. Their hair is also effective in conveying and intensifying a particular mood from gallery to gallery. ↩

- Phillippe de Montebello expressed this anxiety in his foreword to the exhibition Dangerous Liaisons: Fashion and Furniture in the 18th Century: “Unlike natural-history dioramas or historical society tableaux, presentation of works in an art museum is generally without recreating of their original and cultural contexts….In every room furniture remained as originally placed or was only slightly shifted to accommodate the mannequins. The actions of the figures were, therefore, directly predicated on concepts originating from the rooms and the décor.” ↩

- In the exhibition Dangerous Liaisons: Fashion and Furniture in the 18th Century (April 29–September 6, 2004), cocurated by Harold Koda and Andrew Bolton, mannequins performed vignettes based on eighteenth-century paintings in the Wrightsman Galleries. The Met’s description of the exhibition states: “The vignettes, staged for the widely praised exhibition Dangerous Liaisons: Fashion and Furniture in the 18th Century…feature eighteenth-century costumes in the Museum’s spectacular period rooms, The Wrightsman Galleries. The artfully composed scenes include: a woman sitting for her portrait while her husband flirts with her friend; a man being granted an audience with a woman in a peignoir who is having her hair dressed; a vendor embracing the wife of an old man, his back turned, examining a table for sale; a girl receiving more than a harp lesson from her teacher, while her oblivious chaperone reads an erotic novel; a woman giving up her garter as a memento of a very private dinner.” ↩

- Rodin wrote an entire volume on medieval art published later as Les cathédrales de France (Paris: Armand Colin, 1921). Rodin’s engagement with medieval art and memory was resuscitated in a recent exhibition, Kiefer/Rodin, at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia (November 17, 2017–March 12, 2018). ↩

- As Holland Cotter wryly observed, “It (the Met Cloisters) offers an imaginary Middle Ages, but one with real medieval art in it. The demand for this medievalist fantasy has always been strong in the United States. The robber barons of the Gilded Age, with their castle keeps and Anglo-Saxon pieties, looked back to feudalism with a certain fondness.” See “Epiphanies in a Medieval Courtyard,” New York Times, December 21, 2007, at https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/21/arts/21manh.html, as of July 16, 2018. ↩

- See Elizabeth Bradford Smith, Medieval Art in America: Patterns of Collecting, 1800–1940 (University Park: Palmer Museum of Art, 1996). I came to realize the paucity of medieval material in New York public collections before Barnard’s museum while researching the art historian Meyer Schapiro; that research is forthcoming in my essay “Against Primitivism: Meyer Schapiro’s Early Writings on African and Romanesque Art,” RES 71–72 (Spring–Autumn, 2019). ↩

- As Timothy Husband has chronicled, “Everything about the installation of Barnard’s Cloisters was calculated to intimate age and to create a churchlike atmosphere. The walls had been patinated by washing them while the mortar was still wet, and objects had been installed with a contrived spontaneity suggesting change over time, all with little regard to or even awareness of art historical principles.” See “Creating the Cloisters,” MMA Bulletin (Spring 2013), 10. ↩

- For a broad consideration of the Voyages, see Tina Bizzarro, Romanesque Architectural Criticism: A Prehistory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). ↩

- With regard to Barnard’s collecting adventures in the French provinces, Breck noted, “a pigsty might yield the slab of a crusader’s tomb,” in “The Cloisters,” MMA Bulletin 20 (1925), 167. We now know that many of Barnard’s stories of “provenance” were exaggerated or entirely fabricated. ↩

- I have provided a close reading of this lithograph in my chapter, “The Romantic’s Other: the Middle Ages from Moissac to Mérimée,” in “Primitive Before Primitivism: Medieval and African Art in the 19th Century” (PhD dissertation, Columbia University, 2015). ↩

- While Breck was involved in the incipient stages of planning with Collens, he died unexpectedly in 1933. James J. Rorimer completed the planning of the museum after his death. Rorimer would go on to become the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art between 1955 and 1966, greatly expanding the collection of the Cloisters throughout the duration of his tenure. ↩

- Though Benedictine monks took a vow of silence, the space of the medieval cloister was rarely silent, as medieval reading was a performance to aid memory. As Jean Leclercq argues, “What results is muscular memory of the words pronounced and an aural memory of the words heard.” See The Love of Learning and the Desire for God: A Study of Monastic Culture (New York: Fordham University Press, 1961), 73. ↩

- Alexander Potts, “Installation and Sculpture,” Oxford Art Journal 24 (2001), 14. ↩

- On the deliberate nature of the Romanesque sculptor’s and architect’s appropriation of Roman forms, see Linda Seidel, “Rethinking ‘Romanesque;’ Re-Engaging Roman(z),” Gesta 45 (2006), 109–123. ↩

- On relics and reliquaries, see Cynthia Hahn, Strange Beauty: Issues in the Making and Meaning of Reliquaries, 400–circa 1204 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012), and Objects of Devotion and Desire: Medieval Relic to Contemporary Art (Hunter College: The Bertha and Karl Leusbsdorf Gallery, 2011). See also Barbara Boehm, “‘To learned people this may seem to be full of superstition’: Reliquary Sculpture in the Medieval Christian Tradition,” in Alisa LaGamma, ed., Eternal Ancestors: The Art of the Central African Reliquary (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007) 87–95. ↩

- Brown, Bill, “Thing Theory,” Critical Inquiry 28 (2001), 16. ↩

- It should be noted that throughout the exhibition there is also an aural component: “Ave Maria” plays in the Romanesque Hall, the Langon Chapel, the St. Guilhem cloister, and the Fuentidueña gallery; other musical excerpts in the exhibition (in other galleries at the Cloisters and the Met Fifth Avenue) include “Chasing Sheep is Best Left to Shepherds” by Michael Nyman, “On Earth as it is in Heaven” by Ennio Morricone (from the soundtrack for the film The Mission), “Concerto en Mi Mineur, version de 1798” Zbigniew Preisner (used in the film La Double Vie de Veronique), and an aria from the opera La Wally (1892) by Alfredo Catalani. My thanks to Nancy Wu, Senior Managing Museum Educator at the Met Cloisters, for providing this information. The music serves more as a distraction than ambiance, as Jason Farago noted in a review of the exhibition: “Playing in the medieval sculpture hall is an intolerable loop of staccato string accompaniment . . . that will make you wish the Costume Institute would take a Cistercian vow of silence.” Farago, “‘Heavenly Bodies’ Brings the Fabric of Faith to the Met,” New York Times, May 8, 2018, at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/09/arts/design/heavenly-bodies-met-costumes.html, as of July 16, 2018. ↩