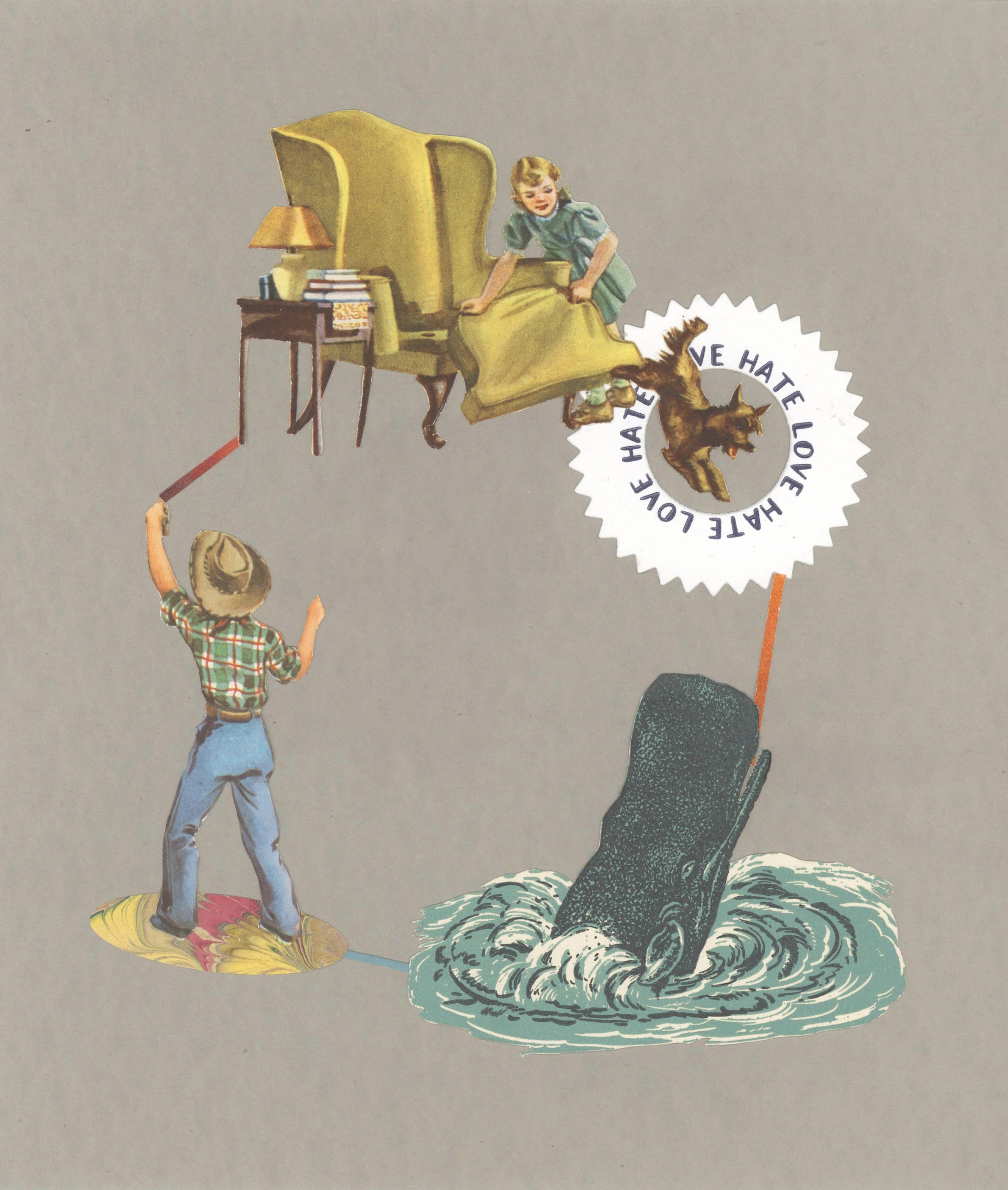

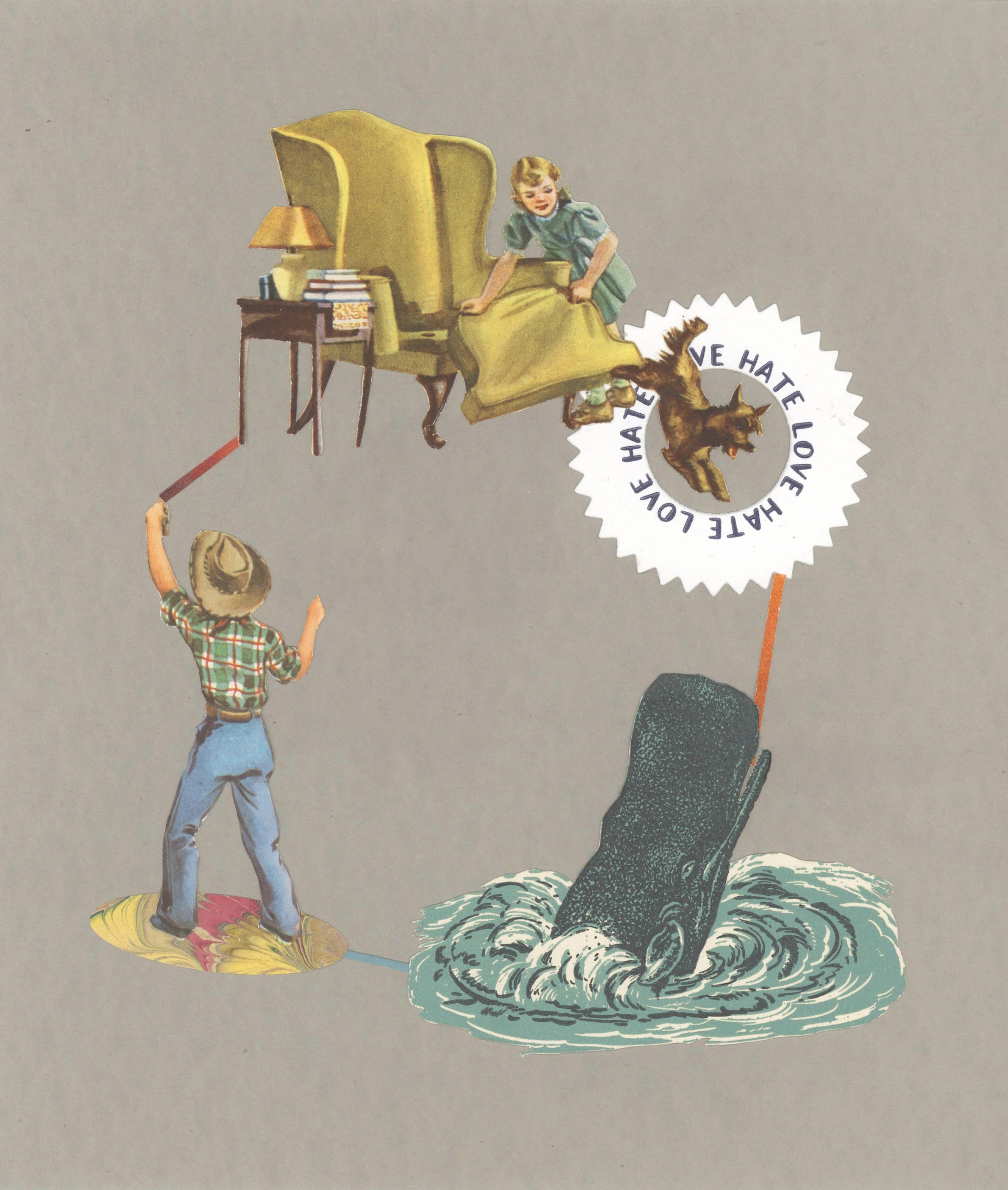

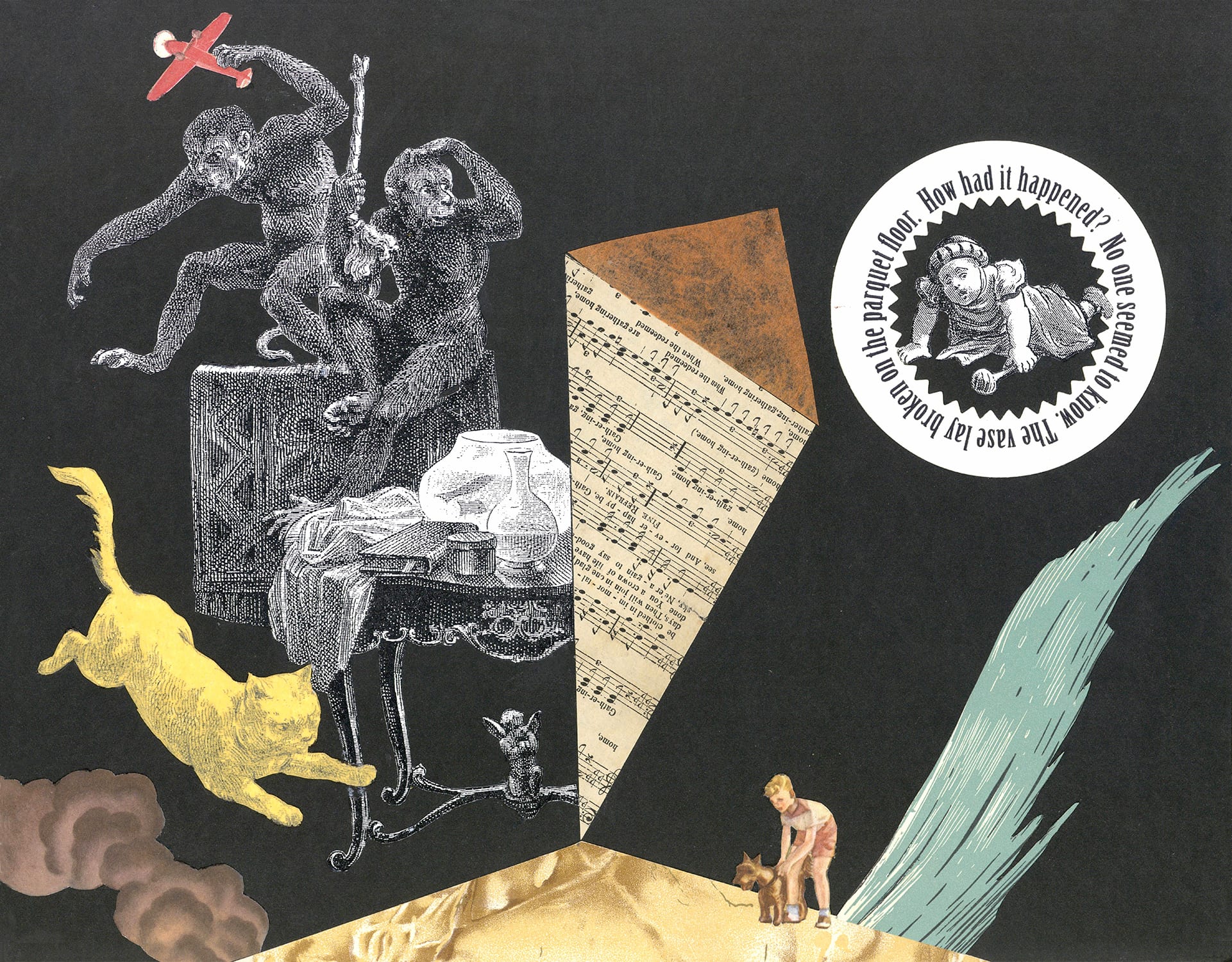

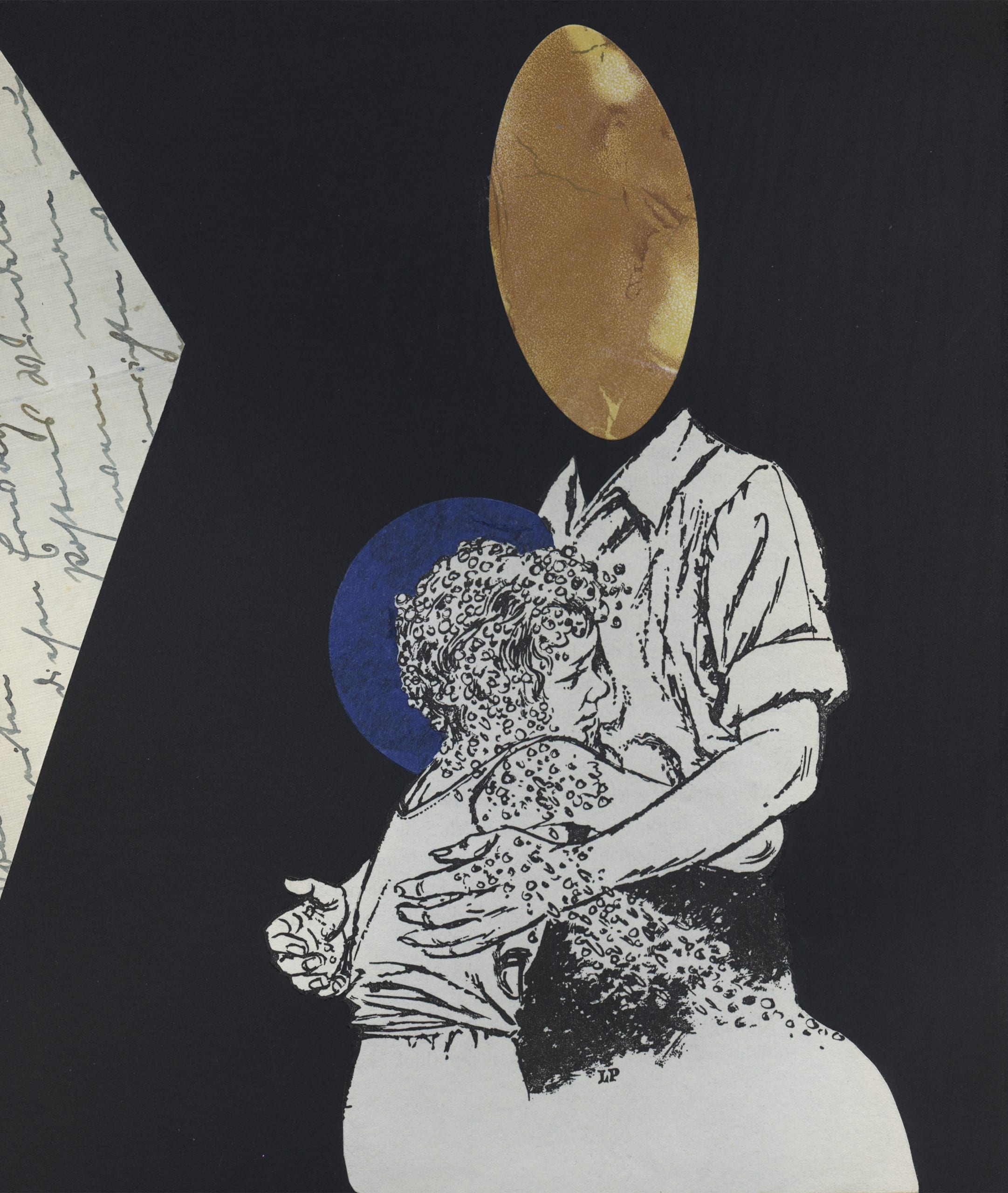

A complicated, lifelong relationship with the printed word lies behind my exploration of books as both physical material and subject matter. A primary source for the collages in this book excerpt is the library left behind by my Anglophile grandmother Mary Löw, a citizen of the late Austro-Hungarian Empire and an avid reader of mediocre German translations of novels by British writers. These volumes—printed in many different old-fashioned blackletter typefaces, all equally impenetrable—were unwanted by libraries or collectors, and destined for landfill by the time I took them in. Their new life as art functions as reclamation of their value and, at the same time, serves as an uncomfortable recognition of the decreasing role of books in a digital media world.

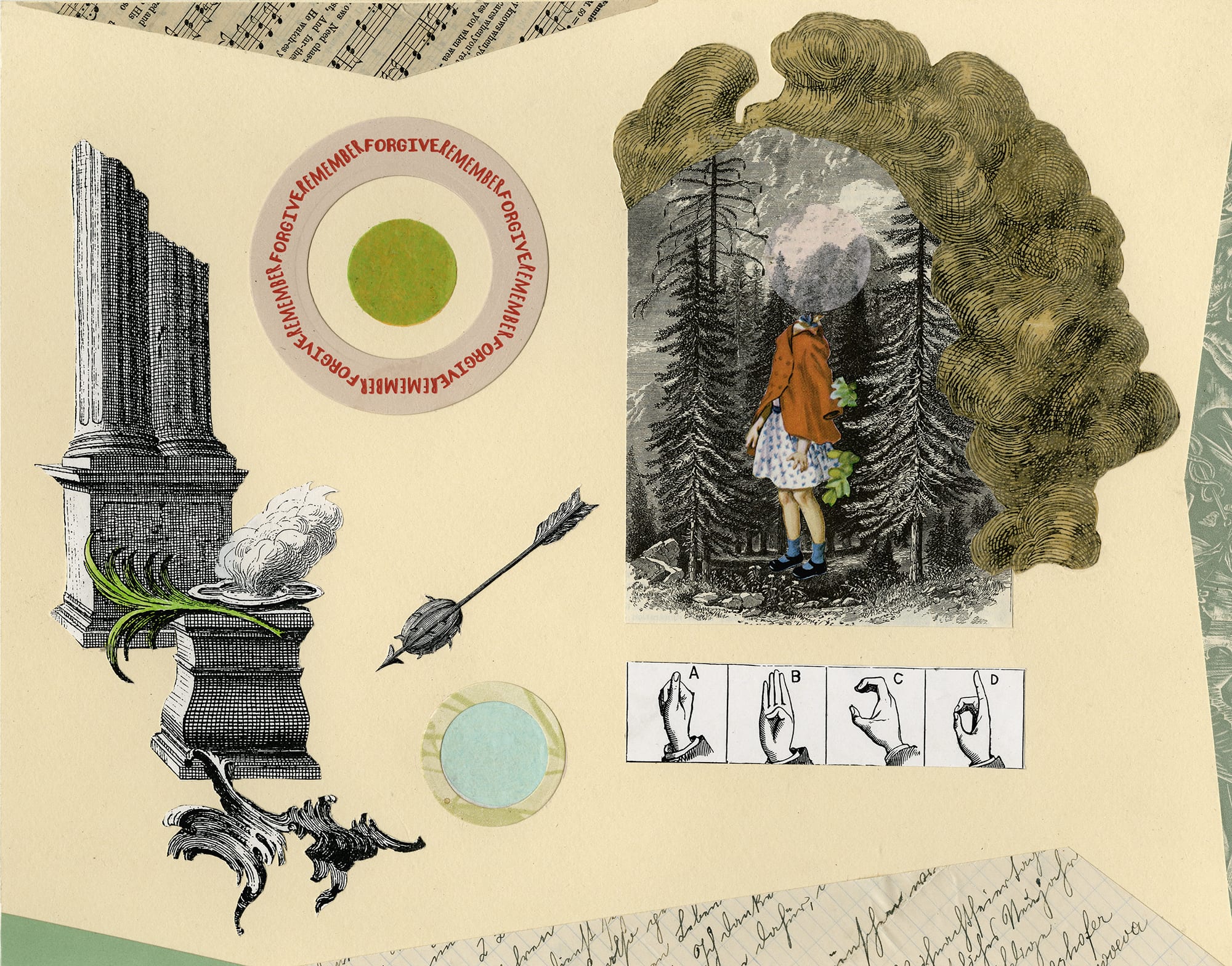

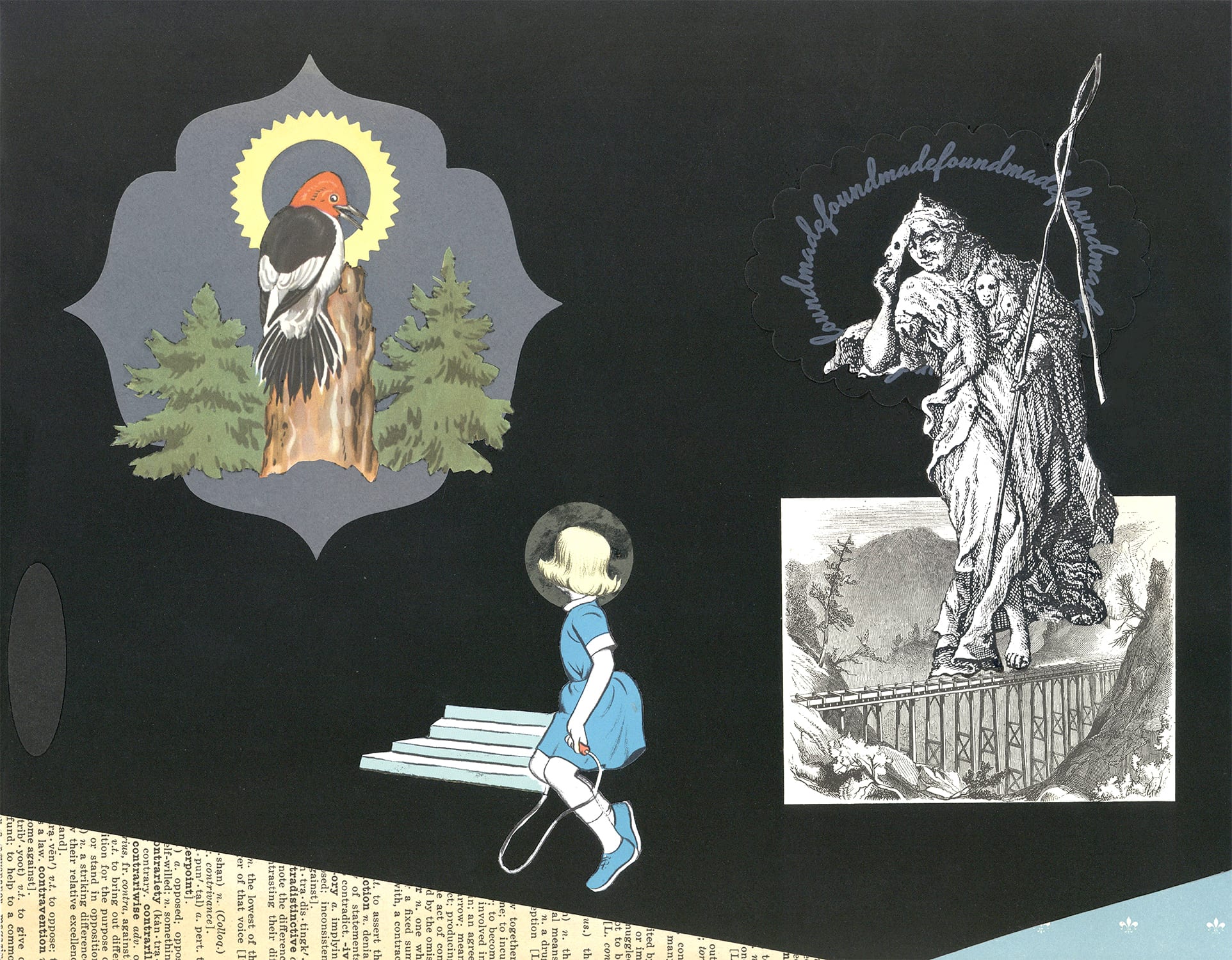

Each collage in Shortest Stories contains a mixture of Old World illustrations, texts and figures from 1960s textbooks and readers, bits of sheet music, and other random ephemera. Gravure images from nineteenth-century novels and snippets from my grandmother’s letters mix with Dick and Jane–style pictures of happy girls and boys, or diagrams from outdated science books and encyclopedias. (Along with the books I inherited, there was a box of her letters, the contents of which are about as mundane as most emails now.)

I pair each completed work with an abbreviated fiction: a paragraph-long piece of writing from a group of one hundred such stories that I’ve written over the past five years. These are a mixture of memoir and complete fantasy, their styles ranging from hard-boiled detective novels to dystopian novels, from fairy tales to pulpy romance bodice-rippers. I write mostly in the first person because I find that it makes it easier for readers to slip from one story into the next. I’ve been writing these brief fictions and figuring out ways to integrate them with images since the late eighties.

Rather than functioning as illustrations, the collages are intended to represent complementary readings to the texts, and vice versa. Both words and pictures come out of the same set of experiences and ideas. The selection that appears here in Art Journal Open has been formatted specifically for this digital publication, but I hope to see the complete 100 Shortest Stories released in print as an artist’s book in 2019. In the meantime, many more of these works can be seen on my website.

Editor’s Note:

Hover over the following images to view Maria Porges’s stories. The images are best viewed on a desktop browser.

Maria Porges, an artist and writer, is an Oakland native. The recipient of a SECA award from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, her studio practice focuses on artist’s books, sculpture, and drawing; over twenty solo shows of her work include exhibitions at galleries, museums, and alternative spaces. She received a BA from Yale University and an MFA from the University of Chicago, and has taught or lectured at many art schools and universities, including Stanford, SFAI, Art Center in Pasadena, the University of California at Berkeley, Cranbrook Academy of Art, and the University of Iowa. She is presently an associate professor at California College of the Arts. Since the early 1990s, Porges’s critical writing has appeared in many publications, including Artforum, Art in America, Sculpture, Glass, the New York Times Book Review, and a host of now-defunct art magazines. She has also authored essays for more than one hundred exhibition catalogues and has twice been in residence at the Headlands Center for the Arts.