“Are you a girl or a boy?” asked Nathanial on our first day of second grade. “No,” I said, then watched his face turn sour. I was on my way to the bathroom, just wanting to pee, and he wanted to know this basic, impossible thing about me. Using the restroom was (and remains) a tribulation, the kind of event that produces us as people. Not just for me, but also for Nathanial. It is the kind of schooling that happens all the time both in the classroom and in the interstitial spaces between, especially bathrooms. The relentless and tedious questioning of my gender that I’ve experienced since birth has created a queerness in me that understands learning as happening through a series of situations that produce all of us in ways beyond curricular plans and outcomes.

From a young age I experienced my self and my body, and specifically my ambiguous gender, as an unwieldy object whose edges were often determined by others. Many school activities are divided by gender, and so much of our social selves are built accordingly. To not belong to the gender binary is to spill over, to be a third thing in search of a good-enough container.1 My Axl Rose–inspired spandex shorts were too tight, my Billabong shirt too loose, my mullet too fluffy—its sides clipped too short. I learned to walk by mimicking my brother’s “bro” gait. I learned to talk by copying my teachers and my parents, who were also teachers. A florid and flurried vocabulary spewed from my tiny, dirty, butch mouth.

At age nine, when I got caught in a downpour riding my bike to school, the school nurse helped me peel off my sopping sweat suit and was shocked to find my tiny kid vagina instead of a tiny kid penis. After her discovery, she insisted on giving me a dress, which was a kind of teaching through correction. In a moment of mutual teaching and learning, I refused the dress and she refused me jeans, so I wore my wet sweat suit all day at school. Despite being soaked, I felt more contained in my own clothing, but I also felt unsafe that day in school. I distinctly remember how hard it was to focus, or play during recess. What I learned that day was how closely connected our capacity to learn and play is to feeling secure in our genders and therefore bodies. We are taught not to make a mess of gender categories: as in math, there are right answers; as in grammar, there is a whole system to maneuver in order to speak or write properly. Math and grammar and gender, not to mention pool parties and dating, reside inside the larger economies of value.

While the idea of a “safe space” may be a myth within this system, one can seek out containers for radical self-determination. Despite what we are taught through experience, gender is not like math or grammar. A long history of colonial domination, not nature or science, produced the gender binary.2 Even while the experience of gender slips and slides, a gender binary is routinely enforced, delimiting the ways we inhabit our bodies and therefore minds, closing off spaces for a degree of safeness and more authentic, liberatory learning.

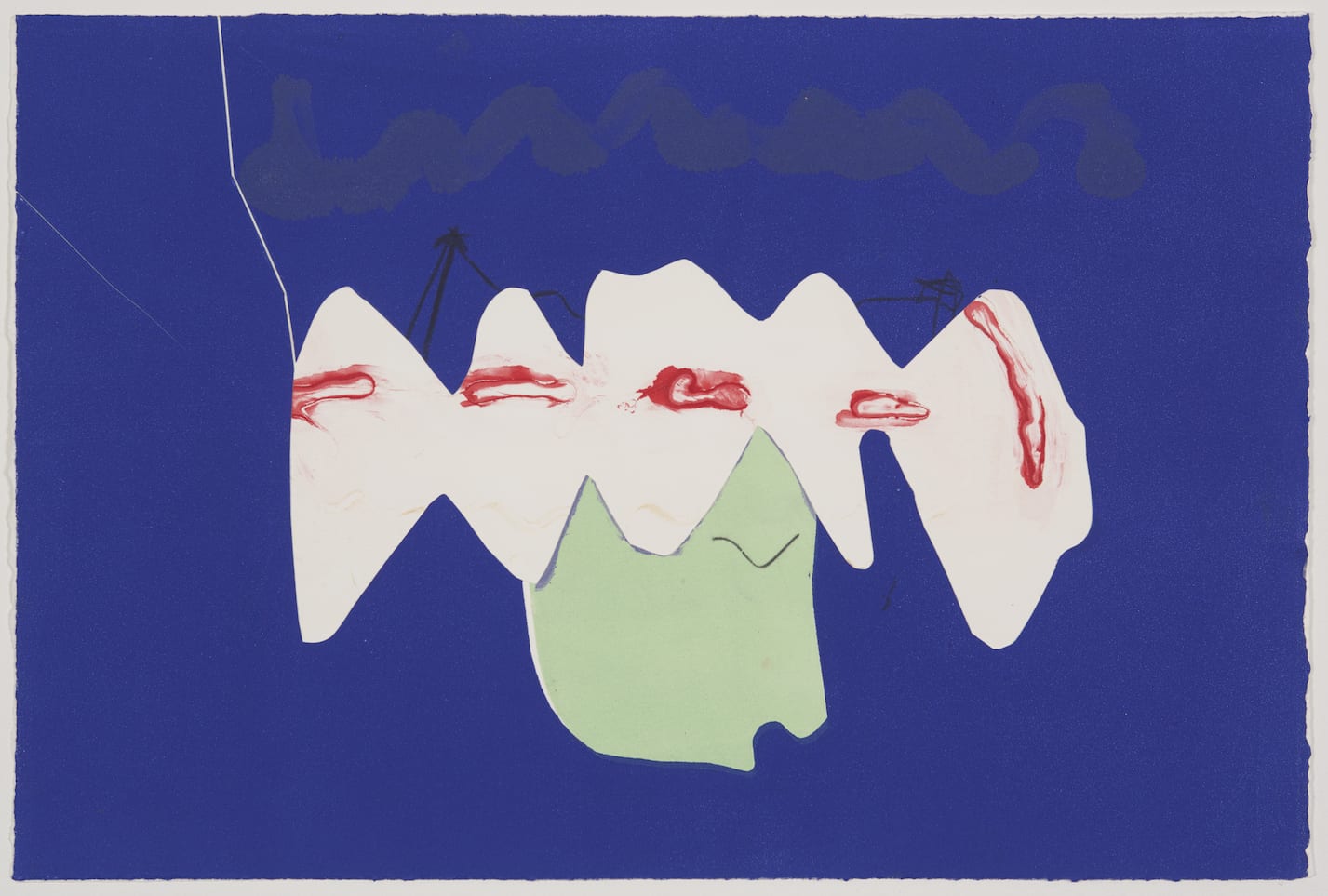

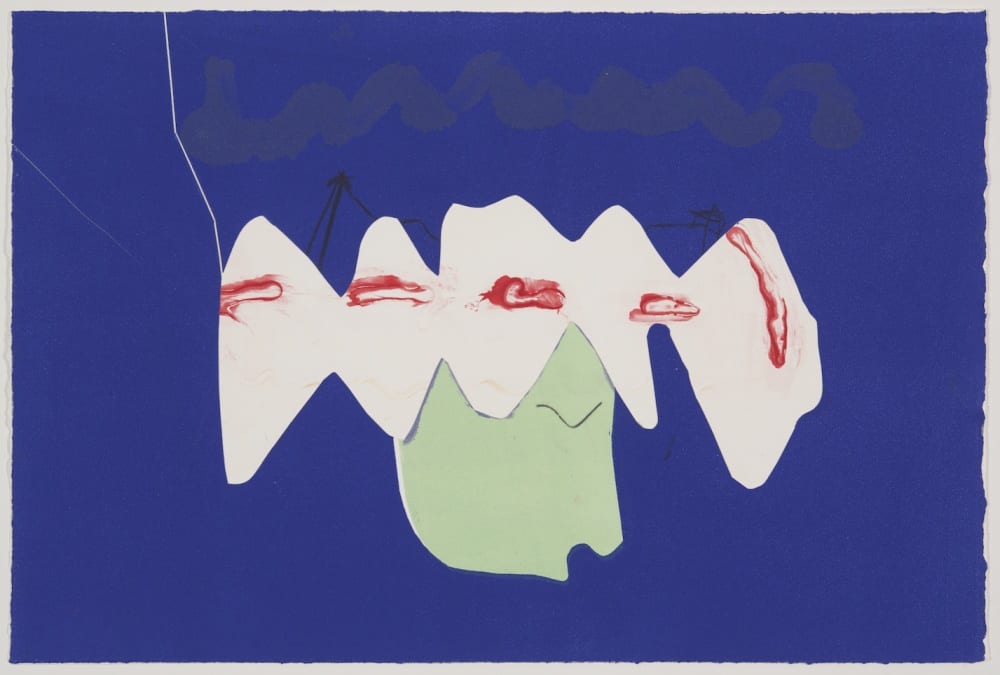

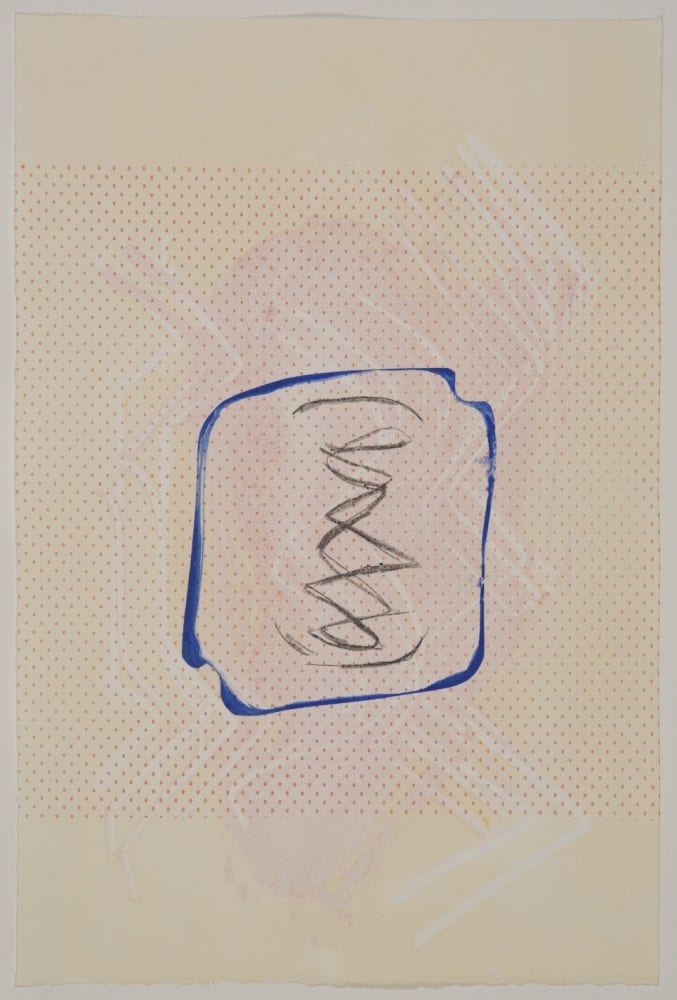

As a queer kid with a messy gender, getting physical was how I could feel my body in space and time, willfully participating in its eventness, even when getting knocked into the mud playing football in the park.3 With puberty came tragedy; I grew heaping breasts and started menstruating. I became a leaking event, an awkward carnal wreckage. Meanwhile, I was falling in love with Rachel and Alison and Melissa and Shanna and Kate. The list is long and blurry and I needed to make every person the most extravagant, elaborate birthday object. My first serious artistic medium was crush art. Imagine Joseph Cornell as a grungy dyke. Notes inside cards inside boxes inside boxes. Coded secrets in envelopes. I began making wildly, feverishly, and hungrily. All my grime and heat fit neatly into beautiful compartments. A place for everything and everything in its place. In a world that perceived me as gender dysphoric, art became my container in which to explore and play. I loved hand-delivering every overwrought package to each girl-friend-crush.

In this way, art for me has always been social—a new kind of grammar, a way of creating a space for my eventness. I went to an arts school from seventh through twelfth grades where it was cool to make things. Within the container of an art school that cultivated experimentation, I fell in love with Rachel and she fell in love back. My art and body began to matter; I began feeling real. While gender and sexuality are distinct things, for me they are bound up in a queerness that was formed creatively, entangled in the sticky fingers of making art. Learning through art and learning through gender were inseparable in my experience. Queerness confronts the edges of identity and spills over. If we spill into spaces that can hold us, we develop the capacity to be present in our bodies and minds, to move and play in our environment. This is the search for the good–enough environment. Because school became safe enough, my gendered body, as a site of both trauma and imagination, formed new possibilities for aliveness, emerging from the desire and effort and urgency to connect. This instilled in me an appreciation for the importance of places of trust in the pursuit of learning, where learners may feel curious or encouraged to try something new.

Using Participatory Practice to Create a Good-Enough Container

Through my position as a teaching artist with the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in Community Partnerships (a subset of the Community and Access Programs within the Education Department), I run art education programs for LGBTQ teens, adults, seniors, people living with HIV/AIDS, people who are impacted by or threatened with homelessness, young adults working towards high school equivalency or GED, immigrant communities, English Language Learners, and kids and adults on the autism spectrum or with developmental disabilities. These individuals fall within the populations that I often hear characterized as “traditionally underserved by museums,” but I prefer to say I work with all kinds of people, all New Yorkers. Some of these programs are interactive tours or art-making workshops in MoMA’s classrooms, but most are longer-term projects occurring at community centers, health care facilities, nursing homes and senior centers.

In many communities that have been fucked—in the United States, by our long history of structural racism in particular—people have been working on issues affecting “underserved” or systemically marginalized people for a long time. These writers, teachers, activists, and artists, as well as my own queer and antiracist communities of peers, have taught me that the best way to make space for others is to share it. As a white teacher working in and paid by a major institution, this often involves getting out of the way in order to make room for others. I am not after a utopian environment; I am working toward a good-enough environment for people to be people.

In the same ways I distrust the term “safe space,” I also think that freedom to self-express should not enable a free-for-all. In every learning environment, we need to balance openness with structure from the start. That structure begins with building relationships to students/participants by offering the day’s plan in a way that creates space for their input, to share what is interesting and curious about the activity, or ask questions about why we are doing what we’re doing. I create the learning space, or what I think of as the “container,” in a way that opens people up to use the activity to develop their own content and pursue their own desires. This cocreation is critical in participatory teaching techniques.4 I begin looking at an artwork by asking, “What do you notice in this image?” and asking the students to share observations. I validate all perspectives with a nod, a word, an eye movement, or a hand gesture. Using these tactics (drawn from the Visual Thinking Strategies theory of arts education), I let the artwork set the stage, and collectively we create an environment for play, where art has the most profound ability to spark spontaneous feelings of aliveness and connection to one another.5

An important piece of my work as a facilitator is close listening, which enables me to reflect what people say back to them, and most critically, link their ideas to others’. Together, we are linking to individual stories, cultures, and communities, using as concrete examples whenever possible. As best I can, I enter artistic and teaching spaces with enthusiastic calm. These practices are driven by patience; I pursue slowness—taking time with each artwork, person, or project in an experiential, kinesthetic, embodied way. This disrupts normative relationships to time and goes against the parts of traditional learning environments that require us to move fast and prioritize quantity over content. All communities are expected to contort to the kinds of time that capitalism values instead of what is needed to move them.6

Art-making and looking help to allows participants’ personal stories unfold in profoundly humanizing and gratifying ways outside of the pressures of time or codified outcomes. Deeper community building can also happen through collaborative art making, like getting students to solve a problem, or work together to figure out what a material can do.

While I appreciate many forms of participation, my education philosophy emphasizes creating a space where people are accountable for their behaviors and comments. Some groups have greater capacities to make community agreements or to reflect on their behavior.7 When confronted by off-topic, passive-aggressive, or insensitive comments, for example, I sometimes choose to highlight the more generative parts of the conversation, while working to avow the other individuals’ involvement. When groups or individuals have greater capacity to reflect, I ask deepening questions (“what makes you say that?”). Accountability is a complex process that involves a sensitivity to power; I am mindful of not letting any one person take up too much space.

Queering and Reclaiming Institutions

Informed by my work as an artist, I develop programs in nontraditional learning environments and toward a broad range of aims—not all of which are institutionally mandated. With an analysis of structural and institutional oppression, my work with MoMA’s Community Partnerships program expands the museums’ use to serve broader communities’ desires. This is the practice of queering the institution.8 For nearly a decade, as part of this practice, I’ve been working with Housing Works, a healing community of people living with and affected by HIV/AIDS, many of whom are black and brown, immigrants, queer and/or trans, and/or struggle with addiction. Over the years we have made tremendous amounts of art in every medium. A large part of my work is figuring out how to best utilize MoMA’s resources to serve Housing Works’ mission. This often does not resemble conventional art education: instead, art becomes a catalyst for self-acceptance, for belonging to a place and time that can hold our pain and pleasure in tandem. Art resides not in the tidy stories of well-placed geniuses who changed the world; art is a practice, it is how we resist the stories stuck to us or stolen from us by those who know nothing about me or you. We talk back, make messes, and value each other’s acts of creation no matter small, no matter how weird.

I do not invoke MoMA to glorify the masterpiece—we have plenty of that in our culture. Instead, restructuring how we use museums is one of many ways we can reimagine art spaces: not everyone experiences their body, space, or place the same way, and while real transformative justice can occur at and through large art institutions, these spaces can also feel like a huge, intimidating, crowded malls selling white, Western culture. (We need to stop singing the praises of Picasso, Pollock, Degas, or Gauguin. Please.) Queerness, at its best, lays bare the power structures that produce us, and celebrates everyday aliveness over linear progress, uncertainty over certitude, our weirdness over normalization, self-expression over self-promotion, and community over individualism.

My goal is not to bring arts or culture to a place, but to bolster, support, and bear witness to the forms of creativity already flourishing. For example, in early 2018, I worked with Housing Works clients and staff to create a massive dance party inspired by the gloriously obsessive work of Yayoi Kusama. We spent a month covering everything in red dots, and dressing the space with piles of red blow-up balls. On the day of the The Love Ball, the Housing Works cafeteria quickly filled with bedazzled, fierce getups and fearless dance moves. Throughout the afternoon’s vim and verve, I found myself thinking about Kusama’s happenings, which reveal the body as psychedelically social, immersed in its context. The party performed queer eventness, infinity-mirrored. People that I had known for years were amplified in a remarkably different way.

A large part of my work is holding space for this complexity: I am working to make the museum and art more accessible while also chipping away at the myth that art museums are in and of themselves important, stable places that we shouldn’t question, tear down, or fuck with. If queering an institution is the work of expanding the normative use of the museum to engage more forms of learning, participatory learning offers an idea of how—through techniques of space-making and community building.9 While the Housing Works Kusama Love Ball was a far cry from a traditional learning environment, it was not without clear goals and strategies. The goal was to cocreate an event, as a good-enough environment, and claim it as art. There were a dozen ways to be involved, from decorating and designing costumes to dancing to just showing up and hanging out. Using participatory techniques such as creating a context-driven project, participant-directed content, and collaborative strategies for art making, the community played an active and meaningful role in developing and designing its ultimate love party. This was a project that helped people feel connected to themselves, to each other, and to art as a place of messy wildness.

My work forces me to confront the reality that participatory art making is not a utopian party. It requires decolonizing myself, decentering and dismantling my white privilege, and holding myself accountable to the ongoing process of making mistakes.10 During the Kusama event, I was engrossed in the photo booth and my desire to produce great pictures. While arranging a group photograph, I touched the arm of a participant and she became hostile. In this encounter, I needed to confront the contradictions between my desire for a photograph and the participant’s need to not be touched. I must recognize that it was a situation where I undeniably had more power than the participant on a variety of registers. Even though I shared queer identity with many folks at that party, my queerness cannot protect me from reinscribing numerous problematic hierarchies like white supremacy and ableism.11 Using participatory teaching techniques, we can explore our mutual eventness as a site of radical shared struggle and transformation, even while confronting these power dynamics.

I often return to the idea of the “eventness” of self, particularly in the context of queerness: the way things never happen alone or outside of their contexts. Queerness has taught me to continuously struggle to decenter myself, and to privilege the relationships between our bodies and the environments we inhabit. Through my practice as an artist, I show up to the messy, weird vulnerability of using art to work with people, and attend to the fine line between where I end and others begin. I work to make spaces spacious. To queer the museum is to pry open its borders or productively spill, rather than increasingly privatize or colonize. Playing with and through art is making way for our eventness; we cannot be curious if our spaces are not good enough. If my work brings about an increase in presence, humanity, aliveness, dignity, embodiment, empowerment, tuning in, or reclamation of traditional institutions like museums, I will have done good-enough work.

Kerry Downey is a freelance teaching artist at the Museum of Modern Art (since 2007). They work in the Education department, running over fifteen Community and Access Partnerships in all five boroughs of New York City. Downey has taught at Hunter College and Parsons The New School of Design, and has been a visiting professor at over a dozen colleges. As an interdisciplinary artist, their videos, performances, and works on paper have been shown nationally and internationally. Like their teaching practice, their artwork explores the relationship between states of embodiment and forms of power.

- D. W. Winnicott, Playing and Reality (London: Tavistock Publications, 1971). Winnicott was an English pediatrician and psychoanalyst who was especially influential in the field of object relations theory. He is well-known for writing about the “good-enough mother” who provides a stable, nurturing environment. This environment creates a sense of comfort and connection to the primary caregiver, allowing the child a capacity to play, a developmental achievement. This theory stood in contrast to the dominant cultural image of an idealized parent generated by professional experts in postwar America. ↩

- Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex (London: Routledge, 1993). ↩

- For me, queerness is about the “eventness” of the self: the way things never happen alone or outside of their contexts. We are bodies in space, place, and time, and our past selves seep into both the present and our imagined future. ↩

- Jules N. Pretty, Irene Guijt, John Thompson, and Ian Scoones, Participatory Learning and Action: A Trainer’s Guide (London: International Institute for Environment and Development, 1995). ↩

- “Our Mission,” Visual Thinking Strategies, at https://vtshome.org/about/. ↩

- J. Jack Halberstam, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (New York: New York University Press, 2005); and Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013). ↩

- “SAFER SPACE POLICY / COMMUNITY AGREEMENTS,” The Anti-Oppression Network, 2016, at https://theantioppressionnetwork.com/resources/saferspacepolicy/. ↩

- Sara Ahmed, “The Institution as Usual: Diversity Work as Data Collection,” lecture, Barnard College, New York, NY, October 17, 2017. ↩

- Jules N. Pretty et al., A Trainer’s Guide. ↩

- Sara Ahmed, “Phenomenology of Whiteness,” Feminist Theory 8, no. 2 (2007): 149–168; and Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (London: Pluto Press, 1986). ↩

- bell hooks, Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (Boston: South End Press, 1984); and Robin DiAngelo, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism (Boston: Beacon Press, 2018). ↩