From Art Journal 77, no. 4 (Winter 2018)

India/Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art. Fotofest 2018 Biennial, exhibition organized by Sunil Gupta and Steven Evans. Various venues, Houston, TX, March 10–April 22, 2018

Steven Evans, ed. India/Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art. With essays by Gayatri Sinha, Nada Raza, and Zahid R. Chaudhary; texts by participating artists; and intro. by Sunil Gupta. Houston: FotoFest, and Amsterdam: Schilt, 2018. 268 pp., approx. 200 ills. $60

Houston, Texas, might not be the most obvious site for what is arguably the most significant exhibition of Indian photography to date, but to take seriously the curatorial conceit of the show, perhaps it should be. The FotoFest 2018 Biennial featured some forty-seven artists of Indian origin from around the world. Titled India/Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art, the exhibition showcased the remarkable diversity of personal perspectives while insinuating that there is still a meaningful unity to the experience of Indian cultural history. Spread across several main venues around the city, including three converted warehouses and the Asia Society Texas Center, the show required several visits to take in, not least because the artists’ visions ranged so broadly in subject matter and approach. Although it would be nearly impossible to articulate a single take-away from an exhibition of this breadth, one issue that the work posed insistently, both as individual pieces and taken together, was how high the stakes are for articulating cultural identity of all stripes. In some cases, this concern was explicitly political, and in other cases highly personal. Most of the work in the show, however, expressed a remarkable commitment to exploring issues of cultural belonging, as opposed to, for example, more abstract formal concerns that characterize other photographic traditions. This may, of course, be explained partially by the exhibition’s explicit geocultural framing. However, it also spoke to the increasing urgency of these concerns in an (art) world that is exponentially global—a world in which the possibility for communication is quickly outstripping the constraints of context.

The exhibition was cocurated by Sunil Gupta and FotoFest director Steven Evans. Gupta is a photographer, curator, and activist who is well known in India (where he was born) as well as abroad (where he has lived for decades, first in New York, and later in London). Gupta’s track record as an established artist and curator across the continents make him a natural choice for a show of this scale and ambition. His photographic practice has focused on documenting queer communities across the many cities he has called home, and this interest in communities that are in some sense on the margins of society is echoed in many of his curatorial choices throughout the exhibition. He is known as an outspoken advocate for both LGBT issues and HIV awareness. Indeed, it comes as little surprise that artists with strong ethical commitments are well represented in the exhibition’s selection.

As a curator, Gupta is largely responsible for having brought early international awareness to the complexity of South Asian contemporary photographic practice. As he outlines in his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, he began curating in the late 1980s and produced influential exhibitions such as Where Three Dreams Cross: 150 Years of Photography from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh (Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2010). As the longest-running international biennial of photography in the United States, FotoFest provides a significant platform for Gupta’s enduring commitment to broadening the conversation about global contemporary photography with South Asian roots.

Gupta and Evans chose to define “contemporary” as works completed in the year 2000 or later. This bold cut-off accounted for one of the show’s great strengths: the inclusion of dozens of relatively young and fresh photographic perspectives. Many of the artists included in the exhibition are not well known even in their home country, let alone recognized by international audiences. In having sought out such new voices, the co-curators demonstrated persistent dedication to forging ever-relevant histories and took an important step in broadening a conversation long dominated by a handful of well-known names. This is not to say that the usual suspects were not included in the lineup: many of India’s best-known artists were represented by their forays into photography. However, to put these established names on the walls alongside a much younger generation of artists in positions of equal standing was a strong and generous statement on the curators’ part, and one that brought more complex meaning to all the images in this mammoth show.

The handsomely produced, 268-page book that accompanies the exhibition is an important complement to a survey of this size.1 Gupta’s introduction offers a brief history of photography in India and reflects especially on the opening of the genre to diverse voices and modes of experimentation in recent years. His text serves to ground the additional three essays commissioned for the show and written by the Delhi-based critic and curator Gayatri Sinha, the London-based curator Nada Raza, and Zahid R. Chaudhary, a professor in the Princeton University English department whose research has focused on early photographic practice in India. This selection of contributors reflects well the geographical scope of the exhibition, as well as the broad range of aesthetic strategies on display.

Sinha’s contribution, “A Fine Line: The Still and Shifting Lens in Contemporary Indian Photography,” begins by addressing photography’s fraught inclusion in the category of art, and goes on to address photography’s engagement with historical and mythological tropes, and its unique ability to allow for ludic self-representation. Most of Sinha’s examples are drawn from the most established artists in the exhibition, but she also discusses lesser-known photographers in the show such as Dhruv Malhotra, Vinit Gupta, Asif Khan, and collaborators Anita Khemka and Imran B. Kokiloo. The diversity of the young artists is in part illuminated by Sinha’s claim that photography is among the first art forms in India that is not bound by the traditional barriers of entry such as caste or association with a guild or family training network.

Raza’s essay, “Impersonation, Self-Invention and Memory: Iconicity and Mimesis in South Asian Photography,” focuses on the particularly prevalent trend of staged photography and its relationship to history, fantasy, and the archive. Indeed, this has been one of the most distinctive modes of photographic practice in South Asia since the inception of the medium. Raza invokes a handful of historical precedents, such as Umrao Sher-Gil’s family portraits, along with the photographic history of her own family to set up her discussion of how contemporary artists inhabit and subvert visual tropes in order to assert their own claims to citizenship and personal belonging. Her analysis draws on the scholarship of Christopher Pinney and engages most substantially with the practice of four women: Pushpamala N., Anita Dube, Anusha Yadav, and Indu Antony, each of whom interrogates norms of class, gender, and sexuality through performance and play.

The performative mimesis Raza articulates extends far beyond the work of these four artists, however. The same impulse surely characterizes the work of Annu Matthew, whose cheeky and meticulous restaging of nineteenth-century photographs of Native Americans undermines the romantic authenticity of these early ethnographic prints. In this series, An Indian from India, Matthew pairs these historical portraits with mimicked doubles in which she adopts the same pose as the original sitter but dons South Asian accessories in place of Native American ones. Hence, Feather Indian and Dot Indian are combined in a photographic diptych that illustrates the absurdity of historical accident.

A less obvious extension of Raza’s discussion might be applied to Mithu Sen’s project, I Have Only One Language: It Is Not Mine—a unique piece that is one of the most affecting in the show. This video work documents a very different mode of performance, in which Sen adopts the persona of Mago, “a seemingly homeless person who speaks her own language.” Mago is not enacted for the camera alone. Rather, Sen fully assumes the Mago persona over the course of several days as she spends time with abused girls in a government orphanage home in Kerala. This is an unusual project indeed, because Sen actively engaged a community of girls whom society had largely abandoned, through a fictional persona. The extended encounter is presented through a series of video clips that document Sen’s varied interactions with the girls, who are often the ones who hold the camera and decide where it is pointed. The final result is displayed with a manipulated color spectrum that at once invokes the specter of surveillance and succeeds in concealing the identity of the orphaned girls.

Sen’s piece relies on strategies of mimicry and performance, but rather than serving to undermine cultural stereotypes, its mode of engagement is intended to promote human connection. Sen sought to build a relationship beyond language with a group of vulnerable young women and decided that a fantasy persona could help her accomplish this. Rather than invoke the specificity of an earlier trope or time, however, Sen intended to enable a realm of imaginative play within the orphanage in which everyone could take part, stating, “It was an experience of intimacy and trust, producing physical and emotional behavior, making all involved believe in an alternative world” (Sen quoted on 116).

Sheba Chhachhi, Temporal Twist, 2017, celluloid film strips, ht. 26 ft. (8 m), installation view, FotoFest, Houston, TX (artwork © Sheba Chhachhi; photographs by Nash Baker)

Chaudhary’s essay “On Finitude” does important work to frame the exhibition’s diverse array of images between two of contemporary India’s most defining sociopolitical hallmarks: neoliberalism and the rise of the religious Right. The author’s background in comparative literature is evident in his generous reliance on cultural theory, yet he offers a handful of keen visual observations within this theoretical framework. He points out how Nandini Muthiah’s practice levies a subtle critique of religious nationalism, while Asif Khan’s images document the tragedy of communal violence. Recalling Benedict Anderson’s theory of “long-distance nationalism,” Chaudhary then turns his analysis to how sociopolitical allegiances have played out among Indian diasporic communities, citing how the works of Matthew, Pablo Bartholomew, and Max Kandhola explore the complexities of race relations abroad. The text then leverages Michel Foucault’s writing on biopower to offer interpretations of works by Chandan Gomes and Vinit Gupta, each of whom engages the vexed notion of home. Finally, Chaudhury’s essay opens up much larger questions about the limits of life, as suggested by his title, “On Finitude.” He explores Malhotra’s hauntingly unpeopled, nocturnal scenes of Delhi’s relatively new suburb of Noida, suggesting that these landscapes are frozen between a neoliberal future and a dystopic past. He also spends time in the difficult imagery of Arun Vijai Mathavan, whose work offers a grisly view into the world of India’s “sanitation workers”—untouchables who for generations have undertaken the work of preparing human cadavers. Chaudhury’s analysis concludes with a reflection on how Atul Bhalla’s serialized images of Mumbai drains represent an “undifferentiated” social whole through a portrait of the city’s waste—an “objective collective reality” that stands against the recent turn toward neoliberal policies and communal politics that so many of the photographers in the exhibition work to resist.

Perhaps the most illuminating texts in the catalogue, however, are those written by the artists themselves, whose range of voices and concerns do so much to demonstrate the imagination and diversity that the essayists aim to contextualize. These short statements range from poetic to declarative, often expressing the highly idiosyncratic conversational styles of their authors. The fact that each artist was generally responsible for his or her own text is especially fitting, given the remarkably personal nature of so many of the images. A significant number of photographers adopt a similar conceptual format for self-expression: images of mundane moments and objects within a physical space of special significance. The quietness of this approach sets it apart from earlier dominant trends in South Asian photography, which more often trained the lens on the spectacle of a person, place, or thing.

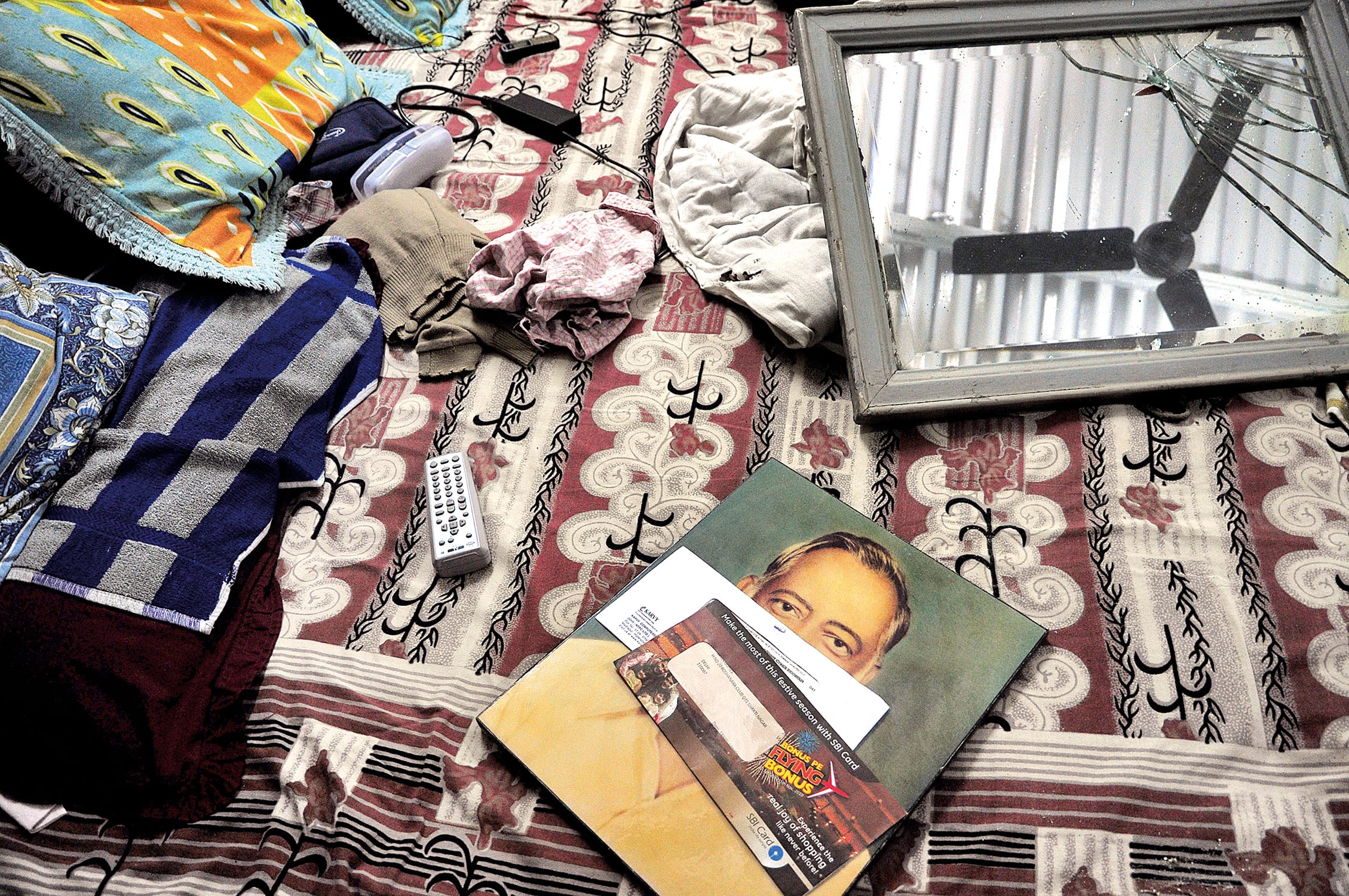

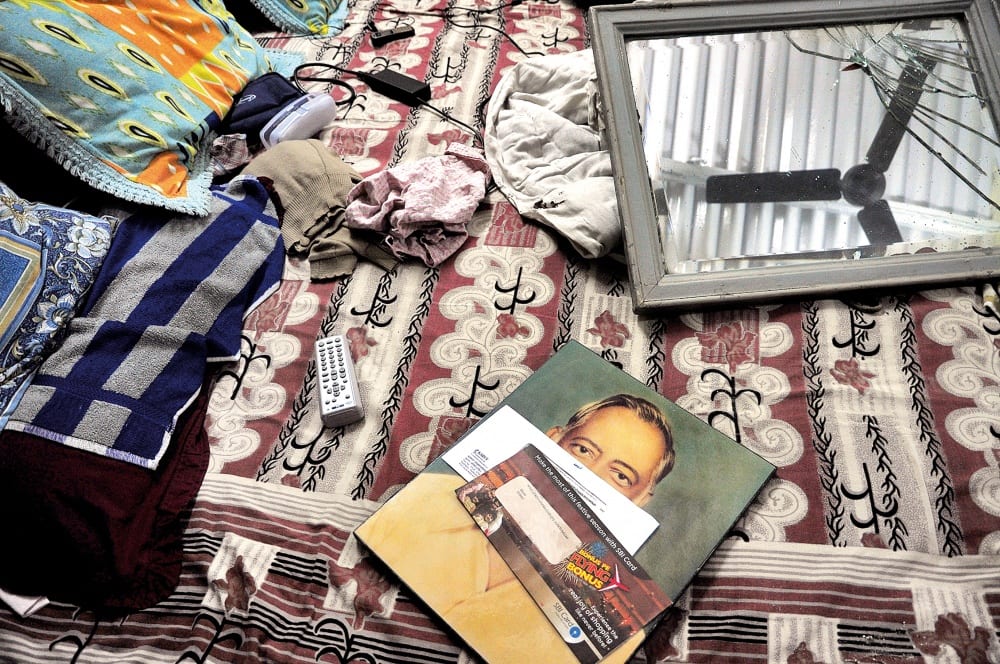

Chandan Gomes is one young artist who adopts this approach with a particularly deadpan sensibility. At first, his pictures look like throwaways or snapshots (except that snapshots are usually “of” something particular—a person or an event). Gomes’s images are unpeopled shots of the interior of his modest family home. We see a cluttered space filled with quotidian objects—shoes, notepads, a broken mirror. Images of Christ and a small crucifix tell us this is a Christian home. Books by Robert Frank and Dayanita Singh scattered among computer equipment and cooking utensils hint at a private passion for photography.

The specificity of Gome’s vision is emphasized in comparison with an earlier series in the show, I-32 TARA by the well-established artist Anita Dube. She too photographs everyday objects in her own home—files, cigarettes, appliances, and lenses—yet with a markedly different approach. Her images are creamy black and white, as opposed to the bright and hectic palette of Gomes’s prints. Dube uses a limited depth of field that contrasts with Gomes’s preference for flatness. Each of Dube’s pictures is subtly composed with a sense of understated balance, while Gomes’s images seem to burst from their frames. In other words, Gomes’s pop-casual sensibility offers a striking contrast to Dube’s more classically orchestrated still lifes—a contrast that exemplifies the difference between one generation and the next, which the FotoFest exhibition illuminates admirably.

Two other young artists who offer intimate self-portraits through the portrayal of space are Hemant Sareen and Dileep Prakash. Sareen’s project, A House Is Not a Home, explores the alienation his family experienced as a result of its move to the suburb of Noida, on the outskirts of Delhi. These images are spare and cold, showing us an abandoned room and a shelf lined with half-empty spice containers. But unlike the pictures by Gomes and Dube, these spaces are not completely bereft of life. One shot shows us the form of an older woman, shrouded in a blanket and lying at the edge of a bed with her back to us. The pale pastels of the bedsheets suggest the dreary ennui of a hospital room. Other images show the many stray cats who came to cohabit an apartment complex. As Sareen describes:

The predicament of the cats mirrored that of the family itself. The cats came in seeking security and played, lolled, slept, and bred within its vastness; soon they were so dependent on it that they were incapable of venturing out. Like the family, they too were incarcerated in this pretty prison. The hostility towards cats and their owners came not just from stray dogs allowed into this gated community, who even growled at the sight of the house’s inhabitants, but also from middle-class neighbors who despised cats as symbols of all their irrational fears (224).

On its own, the picture of the cats in the courtyard is unremarkable, but seen alongside Sareen’s text, the banality of the image becomes itself an index of the daily tedium of this family’s precarious existence. The image of a few sleeping cats suggests how Indian modernization can give way to conditions of profound social isolation. Sareens’s picture combines vacancy with tenderness. His words give meaning to the uncanny atmosphere his images convey. Perhaps it should come as little surprise that the text and image combine so richly in this project, given that Sareen was perhaps better known as a writer and art critic at the time of the show. A House Is Not a Home establishes his firm claim to the language of visual poetry as well.

Sareen’s series invites comparison with What Was Home, another project exploring the idea of personal memory, by the relatively young photographer Prakash. In this set of images, Prakash turns his lens on India’s elite boarding schools. He begins with his own alma mater, Mayo College, and then moves on to similarly regimented and exclusive residential schools across the country. These unpeopled images share a formal rigor with the atmosphere of the institutions themselves: desks, beds, and sheets, perfectly aligned. Prakash lights such elegant and static scenes with lush contrast, and composes each shot with impeccable balance. If Gomes and Sareen index middle-class domestic space idiosyncratically, Prakash offers a more classical treatment of the boarding schools attended by many from the country’s upper classes. Yet his project is guided by a similar set of emotional motivations: “My aim is not only to reminisce and explore my own memories, but also to project them on familiar spaces once associated with feelings, including fear, loneliness, and surprise” (205).

Generally, the older artists tended to produce work that is more abstracted from their own biographical experience than the younger generation. Shilpa Gupta, for instance, presented an interactive video installation from 2007 in which the viewer’s shadow slowly “attracted” visual detritus that was projected from behind, triggering the discomforting sensation of being somehow smothered or attacked by undecipherable forms. The longer one remained in the space of the installation, the more baggage one’s shadow acquired, eventually obscuring one’s human form altogether. At turns delightful and unnerving, this installation was popular among the thoroughly diverse opening night crowd. While the project was very much in keeping with Gupta’s broader practice of exploring the intersection between technology and high art, it was hardly a comment on the artist’s personal identity.

Similarly abstract and formally innovative was Sheba Chhachhi’s colossal Temporal Twist, a twenty-six-foot-high kinetic sculpture made of old celluloid film footage. The strips of film slowly rotated by turn in opposite directions, causing the large column to constrict at its middle, forming a taut hourglass shape that threatened to snap magnificently under pressure. Just before the tension became too great, the mechanism reversed direction, and the film opened out into a gigantic hollow column, and then slowly constricted once again close to the breaking point. The mesmerizing theatrics bound the viewer to the spot, and invited reflection on the fragility of the archive and malleability of cinematic memory.

Other senior artists adopted a somewhat more straightforward documentary approach, as in the elegant Mumbai Walk and Piaus (Water Spigots) projects by Atul Bhalla, Rashmi Kaleka’s hypnotic Hawker Ki Jagah video-and-sound installation, and Gauri Gill’s breathtaking black-and-white photo series Jannat. Bhalla extended his decade-long concern with the state of water through a serialized documentation of the drainage system along the iconic Mumbai street known as Marine Drive and the multiplicity of free water spigots in his native city of Delhi. The simplicity of the project’s framework both highlighted the visually arresting diversity of urban water sources and drew attention to the idiosyncrasies of the lowly but indispensable city drain. Kaleka paid homage to the aesthetic texture of the urban landscape by documenting the uniquely melodious calls of Delhi’s street hawkers. She collected the recordings over many years, aided by carefully considered relationships of trust between the work’s subjects and herself. Overlaid on dreamlike video footage of the city’s rooftops at dawn, it made for one of the exhibition’s most compelling evocations of place—a judgment frequently expressed by viewers who often stood entranced for much longer than they anticipated. Finally, Gill’s Jannat, also profoundly relational, bore witness to the life of one family struggling to survive in the rural Rajasthani desert. Her small and intensely beautiful photographs drew one into the story of a family that is set off by letters written by the subjects themselves, shedding light on the tender interactions and harsh conditions that characterize their complex lives. While each of these projects stem from a deep personal investment on the artist’s part, none would be considered autobiographical in a traditional sense.

What can we make of the fact that so many of the younger artists, by contrast, were drawn to modes of cultural autobiography? The rise of Instagram and Facebook certainly has some place in this apparent trend. Yet there was little trace of selfie-culture in the photographs on display. Rather, the images showed a profound commitment to the idea that the self is inextricably tied to the places, objects, friends, and expectations that make up one’s experience of the world.

Sophia Powers received her PhD from UCLA in 2018 and will join the faculty at University of Auckland, New Zealand, as the Marti Friedlander Lecturer of Photographic Practice and History in 2019. A specialist in modern and contemporary South Asian art, her interdisciplinary research now focuses on questions of feminist art practice and global contemporary art in the public sphere across broader Asian and postcolonial contexts. She is currently working on a book manuscript exploring photographic practice in India marked by intimate, long-term engagement between artists and subjects.

- There was also a separate catalogue, consisting of photographs, texts, and bios of the artists, for which participating exhibitors paid to be included: FotoFest 2018 Biennial Catalog (Houston: FotoFest, and Amsterdam: Schilt, 2018). ↩