Haz clic aquí para leer este ensayo en español.

From Art Journal 78, no. 1 (Spring 2019)

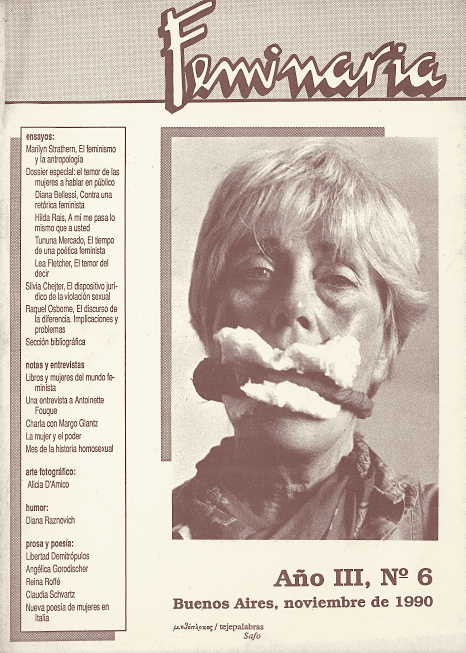

Alicia D’Amico (b. Buenos Aires, 1933–2001) was one of the most important Argentine photographers of the twentieth century, founder of the Consejo Argentino de Fotografía, and cofounder along with Cristina Orive and Sara Facio of the publishing house La Azotea, a pioneer in Latin American photo books. She was widely recognized for her portraits of prominent writers—such as Alejandra Pizarnik, Olga Orozco, Pablo Neruda, Jorge Luis Borges, and Julio Cortázar—and for her series published in books, especially Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires (1968), Humanario (1977), Podría ser yo: Los sectores urbanos en imágenes y palabras (It could be me: Urban neighborhoods in images and words, 1987), among others. Nonetheless, the works relating to her involvement with women’s movements and her commitment to feminist activism, which led her to important projects in photographic research and documentation, were hardly exhibited in the photographer’s lifetime and, since her death, have been nearly forgotten.

Toward the end of the last Argentine military dictatorship (1973–83), D’Amico began research on female identity, using the genres of portraiture and the nude. This led her to delve into subjectivity and lesbian desire, in the context of a country that was starting to recover its freedoms.

For D’Amico, these photographic genres were central when it came to analyzing the impact of heteronormativity on desire and the female body. In turn, the fact of confronting women with their own images could lead to questioning the hetero designation. The photographer explored the subjectivity of those she portrayed to reach what she called woman truth, that is, a woman whose image reflected her desires and her personal choices. Later, she decided to study lesbian desire in relation to the search for a visual imaginary that accounted for sexual diversities.

The present essay seeks to analyze a series of photographs by D’Amico that form part of this research. Starting from the idea of the nonexistence of a single form of lesbian desire, nor of a single form of representing it, I will linger over D’Amico’s need to think about subjectivity, to review it and reinscribe it in images that reflected dissident and destabilizing identities in the heteronormative visual imaginary.

Brief Feminist Context during the End of the Last Argentine Military Dictatorship

I think one of our greatest achievements has been to strip down and highlight the fallacy of male discourse on justice, democracy, and equality, which always concerns gender in a unilateral way. We are clear that we aspire to the same thing and that if no gender has achieved democracy, justice, and equality, we women have always suffered it to a greater degree. We want a change and getting it won’t be easy. We will have to express it from a new ethics and from a new aesthetics.

—Alicia D’Amico1

Following the coup d’état of March 24, 1976, a sudden interruption took place in Argentine culture with regard to the experimentation that had been developing since the 1960s. The profound tearing apart of this milieu, due to the disappearance, exile, or inner exile of many of its protagonists, was not sorted out for a number of years after the return of democracy.2

The de facto government reduced and then paralyzed the action of various groups who had been fighting since the late 1960s for sexual liberation, the autonomy of women’s bodies, and abortion, among them Unión Feminista Argentina, UFA (Argentine Feminist Union), Movimiento de Liberación Femenina, MLF (Women’s Liberation Movement), and the Frente de Liberación Homosexual, FLH (Gay Liberation Movement). In a context where people were advocating for social change, these groups from the late 1960s and early 1970s suggested that social revolution was impossible without first bringing about a sexual revolution, that is, the end of the patriarchy had to happen before the end of capitalism. Along with study groups and theoretical discussions, there was also direct action: the distribution of leaflets on the street and the boycott of sexist events or those that held a pathological view of homosexuality. Fanzines were also produced, as well as publications like Somos (We), the FLH magazine that came out between 1973 and 1976, and Persona, the MLF publication that appeared between 1974 and 1982.

Once democracy was restored on December 10, 1983, the country slowly witnessed the reconstruction of affective bonds that had deteriorated during the regime. The return of exiles had an immediate impact on the cultural realm. Likewise, feminist groups that had started to come back together during the last year of the dictatorship continued with the struggles launched in the 1970s.

In that sense, toward the end of the de facto government, Derechos Iguales para la Mujer Argentina, DIMA (Equal Rights for Argentine Women), the institution founded by Sara Rioja in 1976, organized three important activities that showed the underground work carried out by local feminism, highlighting the urgency for Argentine women of themes such as domestic work, labor rights, health, family, and creativity, among other matters. One of those activities was the First Argentine Congress of La Mujer en el Mundo de Hoy (Women in Today’s World), October 25–26, 1982. A second was the Jornadas de la Creatividad Femenina (Congress of Female Creativity), April 1–3, 1983, whose motto was “In every woman there is a creator and in every creator there is a woman.” Finally, in May of that same year, the Second Congress of La Mujer en el Mundo de Hoy (Women in Today’s World) took place.

It was then that, thanks to the feminist Marta Miguelez’s idea during the Jornadas de la Creatividad Femenina, on August 13, 1983, Lugar de Mujer (A Woman’s Place) opened its doors in the city of Buenos Aires.3 The women noted the objectives of their establishment on the day of its inauguration: “Because we are going to meet in order to talk about ourselves, developing respect and solidarity, examining the conventional models of social bonding. Because we are conscious of the need for a permanent place to meet. Because we want to examine the prejudices and taboos that disparage and devalue us. Because we want to review the models within which we were educated. Because we think that authoritarianism, rivalry, and competitiveness threaten a creative and authentic way of life. Because yes. For what? To reflect on our inclusion in society; to discuss our body, sexuality, emotions, creativity, bonds, identity.”4

Lugar de Mujer was a pluralistic space that welcomed women from all political inclinations, feminist or not. It presented activities, workshops, art exhibitions, film showings, and debates that had an impact on feminist creative production. Such proposals were offered without interruption for five years, 1983–88, after which the space was fully devoted to counseling and helping women with problems of gender violence, leaving aside matters related to artistic and cultural practices.

One of the founders of this space was the photographer and feminist activist D’Amico, who gave various workshops with the psychologists Graciela Sikos (b. Buenos Aires, 1949) and Liliana Mizrahi (b. Buenos Aires, 1943), with whom she explored questions of identity, particularly with regard to lesbian desire and the female body. Both women delved into a series of photo-performances that took into account the results of these experiences in which they worked directly with subjectivity to reach what D’Amico called woman truth—an image of a woman in which her personal choices and desires were manifest, that which she felt she was, far from any patriarchal mandate.

In turn, D’Amico’s personal investigation of the female portrait led her to employ it as a fundamental tool for taking apart the visual framework that crystallized around women in social and domestic mandates, ideas about beauty, and so forth. So central to her work were the genres of the portrait and the nude that on the basis of them the photographer analyzed the impact of heteronormativity on female desire and the female body.

Lugar de Mujer fostered a good deal of interaction between the local artistic realm and feminist activism. The female artists brought problems and debates to the space, while in their works the feminist ideology that circulated there began to take on meaning, bringing with it a golden moment in Argentine feminist art. Between 1982 and 1986, D’Amico created a series of works worthy of analysis and significant for the history of Argentine art.

Being Protagonists of Our Own Life

The task pertains to the group and contains the not-so-secret aspiration to achieve an image of the new woman, a woman seen by herself. A woman truth.

—Alicia D’Amico5

The “new woman” was a category used by second-wave feminists in Buenos Aires to refer to those who had gained consciousness of their oppression in the patriarchal system and thus were seeking to be protagonists of their own lives, fighting for the equality of their rights. When D’Amico mentions the new woman, in the above epigraph, she is making reference to her early feminist activism within the UFA. The members of this group had expressed themselves openly on the subject in their “Manifiesto de la Unión Feminista Argentina.” The new woman is “mentally young, vital, lucid, and determined.”6 That is,

The NEW WOMAN refuses to keep being always a minor in age, and says ENOUGH ALREADY WITH DIFFERENCES. Sexual and salary discrimination, political marginalization, parental rights, economic subordination, marital dependency, non-remunerative domestic duties, the slavery of these duties unshared by the man along with a job outside the house, undesired pregnancy, commercialized eroticization of the woman, a different morality for each sex. These are some of the notorious differences. While they exist it’s impossible for the woman to consider herself and to be considered a complete human being. They’ve made us rivals. We discover ourselves to be sisters. We call out to all women, without social, political, cultural, or generational discrimination, to find solidarity with this movement which has as its prime objective to create a NEW consciousness.7

The struggles of the 1970s, far from falling into oblivion, continued into the 1980s. Nonetheless, we can infer that for D’Amico the new woman, who was seeking civic equality and fighting for her freedom, could only complete her liberation by creating her own image, an image that reflected her identity. The new woman was transformed, therefore, into the woman truth.

D’Amico and Mizrahi met during the First Argentine Congress of La Mujer en el Mundo de Hoy, in October 1982. That same year, D’Amico had begun her investigation into the female gaze, and later remarked: “At the end of 1982, I started a series of works that drew on the female gaze and its translation to photography. There were multiple objectives. The first was to develop the hypothesis that a female gaze exists. That gazing from our internal selves, in a new way, can result in a new esthetic that redefines the current concept of beauty. The second objective was to use the photographic image exhaustively as a vehicle for knowledge and self-knowledge. To that end, working with one’s own image—with portraits—is essential as the direct referent of our identity.”8 In that sense, the photographer worked with the psychologists Sikos and Mizrahi in the workshops that focused on this research.

The hypothesis of the female gaze directed her to other subjects, such as identity and desire. The female gaze as well as identity were studied in the workshop “Autorretrato” (Self-portrait), with Sikos, and in “Imagen y cambio” (Image and change) and “Violencia,” (Violence) with Mizrahi, which I discuss below. Desire, and particularly lesbian desire, were the protagonists of two photographic series: Pies desnudos (Bare feet) and Desnudos de mujeres (Women nudes). In this essay, I focus only on the first of these.

In April 1983 D’Amico gave a workshop about women photographers during the Jornadas de la Creatividad Femenina, which consisted of showing images by women photographers, describing the language used by them, and the gender markers present in their work. Mayra Leciñana, one of the youngest assistants at that workshop, recalls that she learned about the American Diane Arbus there: “She showed how women dared to photograph different things, like Diane Arbus who photographed monstrous elements. She spoke about the ruptures that women artists were making. At the same time, she would compare that with male photographers, like Pedro Luis Raota, who had recently done some photos of pregnant women that were in fashion; D’Amico problematized maternity, suggesting that it was a representation from the perspective of the male gaze. The things she said were very powerful for me, young as I was and only beginning to get involved in feminism.”9

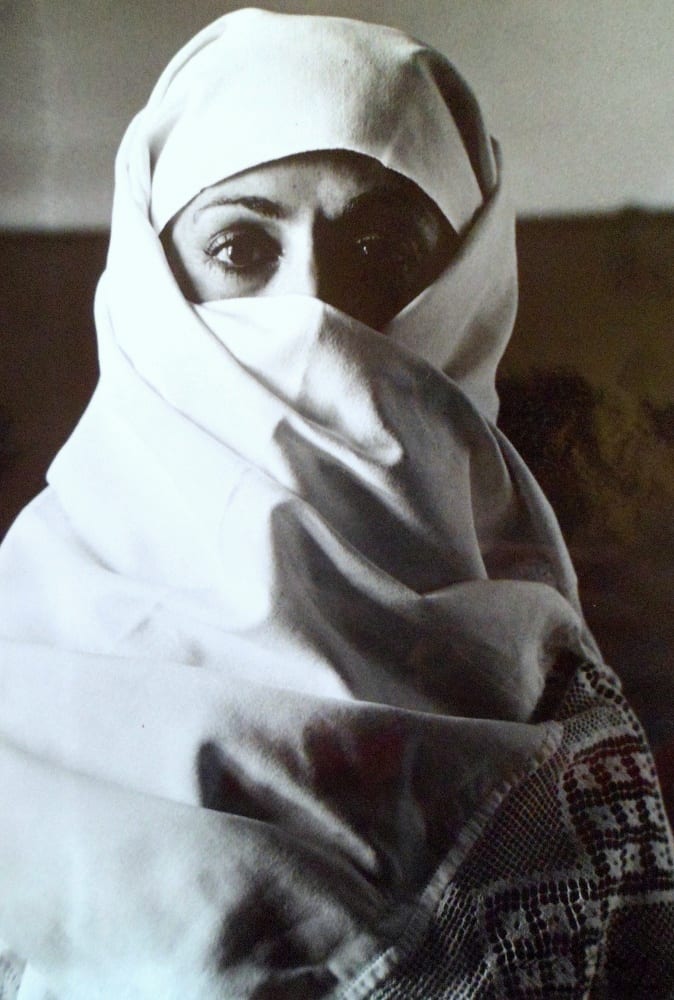

D’Amico’s workshops were spaces of consciousness raising, based on the ideas that the gaze was not a single thing but rather multiple, and that identity was not something established in essence but rather had to be constructed, depending on each woman’s situation—the concept of Simone de Beauvoir, whom the photographer knew quite well through her participation in UFA. D’Amico articulated the need for various images of women to circulate, that those images should arise from women’s own knowledge of themselves and should question the images popularized by visual media of the time—especially by the publicity industry—in which images of women were stereotyped by and for male desire. To that end, she conducted an experiment at the First Argentine Congress of La Mujer en el Mundo de Hoy, as she remarked: “I had the preconceived idea to record women as I see them, without the whole thing getting precious, sophisticated, mystified, and unreal, as some media present the matter. I decided to do portraits the way I like to, in 35mm and natural light, and so I did. I attended the Congress, which was being held on an upper floor; from one window a beautiful light came in that varied according to the different times of day. When the light seemed right to me, I asked whatever woman passed by to pose for a photo.”10

Critiques of the visual representation of women were central to Argentine feminist circles in the 1970s. Through the reading of foreign texts, as with de Beauvoir, or the Canadian writer Shulamith Firestone in her 1970 book The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (who reflected on this theme in the section “(Male) Culture”), local feminists deepened the critique of their own problem, while situating their troubles in a broader context.11 That accounted for many articles appearing in the magazine Persona in the early 1970s. In 1982 Leonor Calvera, a member of UFA, published the book El género mujer (The Woman Gender), in which she denounced the erotic use of women’s bodies to sell publicity for every type of item.12

In the field of international feminist art, the discourses of theoreticians such as Kate Millet, Germaine Greer, and Firestone had their correlative in a number of artistic works. In that sense, it is important to mention Martha Rosler (b. Brooklyn, NY, 1943) and her series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain (1965–74), made up of thirty photomontages that used images from advertising to develop a scathing critique of the ideal of beauty imposed on women; Sanja Ivekovic (b. Zagreb, Croatia, 1949) and her series In Double Life (1975), comprising sixty-two pairs of images that formed an artist’s book and that juxtaposed photos of her adolescence with advertising shots of models from women’s magazines; and various performances produced at Womanhouse (Los Angeles, 1972), among other examples.

In Argentina, on this topic, María Luisa Bemberg, a cofounder of UFA and friend of D’Amico, created the 1972 short film El mundo de la mujer (Woman’s World), in which she attacked female models of beauty, promoters of many products whose main purpose was to boost consumption. Meanwhile, D’Amico’s concern about the female visual imaginary was shared by another photographer and feminist activist, Ilse Fusková (b. Buenos Aires, 1929). In her 1982 series El Zapallo (The Pumpkin), she reflected on female nudity and women’s recognition of their own bodies. She noted,

Most of us women in Western culture see ourselves through the distorted gaze of a society dominated by men. This is true for our entire being and especially for the perceptions we have of our own bodies. . . . I think that the woman’s body is an object of desire for the male, that that body fascinates him and also frightens him. Still, the naked body of a woman, without the contortions of seduction, is a forbidden image. . . . The nakedness of a woman’s body is a right that is absolutely denied to us.13

At Lugar de Mujer, D’Amico and the psychologist Sikos organized the workshop “Autorretrato” with the aim of delving into female identity. It consisted of two four-hour meetings, one in the photo studio that D’Amico shared with the photographer Sara Facio and the follow-up in the Lugar de Mujer space. The theoretical bases they used came from the field of psychology, specifically psychodrama and epic theater. The goal was to encourage a meditation on female identity that could be reflected in images. Sikos recalls,

The idea of doing women’s portraits was Alicia’s, and I added the methodology of the workshop, that is: to do some body work, some relaxation, to bring elements to work with. I brought all the objects we used in the photographs. The women chose which element they would use for posing; there was a mirror they could see themselves in, they determined the forms in which they would pose, and so forth, and Alicia respected those decisions. Then, at the moment we presented the photos taken by Alicia, I got each woman to say how she saw herself and what occurred to her while facing her own image, by way of a questionnaire. We were all together but we gave out the photos one by one. I took notes on how each woman responded. The idea of the questions and of listening to what went on with them as they faced their own image was mine. That’s a self-portrait for me, when you see yourself, when you have the photo in your hands and you recognize yourself, you say “this is me.”14

Mayra Leciñana, who conducted one of the “Autorretrato” workshops, for very young women specifically, recalls:

At the start, we proposed a moment of letting go, of diversion; for example we walked around with our eyes closed, to enter into an atmosphere of relaxation. After, Graciela Sikos gave a talk proposing the idea that one can construct oneself. So she suggested we think about how we would like to be seen, how we perceive ourselves. They brought many elements for us to play at showing ourselves in a role that would relate to how we saw ourselves: gloves, clothes, shoes, cloaks, lace flowers, ties. Once we chose to take on that role, Alicia took our photo. Finally we did an assessment, an evaluation of how we felt about the photographic image that resulted from this process of reflection.15

The participants responded to questions that Sikos drew up to help them express what they felt looking at the photo; those texts accompanied the images. The material from this workshop formed part of the show that was presented at Lugar de Mujer at the time of its first anniversary.

The press took note as well. The newspaper Tiempo Argentino published some photos from “Autorretrato” in an article by Sara Facio, who observed, “The self-portrait is, by definition, the search for one’s own image. Every artistic discipline (painting, literature, etc.) has magnificent examples. We are looking at the self-portrait of a non-artist, of someone who is only searching for their identity, by creating oneself though the technical hand belongs to an ‘other’ woman. But, attention, an ‘other’ who looks at her without prejudice, with no preconceptions, who is only the mirror. And that corresponds to the main idea of the self-portrait: self-knowledge and a noncomplacent acceptance of the self.”16

Part of the material that came out of this workshop was published in the newspaper alfonsina, which had begun to circulate in December 1983. With the aim of articulating the female in the national context, this publication reflected various feminist discussions as well as their impact on the political reality.17 In the article entitled “Cómo Somos” (How we are), D’Amico explained the meaning of the “Autorretrato” workshop: “The working hypothesis maintains that a female photographic gaze exists capable of creating a new esthetic, redefining the traditional concept of beauty; looking in a different way, judging and creating in a different way. Women can transform the image of women. . . . Female identity has now come to be a question for women.”18

Beyond an essentialist reading and/or raising arguments that would lead us to the woman-nature binomial—subjects I don’t think the photographer was interested in—D’Amico proposed to investigate how the freedom over one’s own desire and the female body could create other images of women, different from those that circulated in the mass media of the day. The genres of the portrait and the nude were central to that.

In effect, the photographer analyzed the impact of heteronormativity on constructions of the feminine. Those consciously aware women, who questioned the heterosexual ideological system, sought to create images that went beyond those regulated by the patriarchy. Photography, for D’Amico, became the medium that permitted self-knowledge. She indicated as much in a text from 1984: “We women receive the standards of our social identity through laws, institutions, and customs. It comes into being through the image and the word. Social condemnation, the ‘what will they say,’ as soon as we move away from established conditions, acts as a censor and a restraint to any independent gesture. We women are conditioned by the images shown us of other women, prompted externally by society.”19 Given the recovery of freedoms that Argentina was going through then, it was becoming urgent for women to think about how they wanted to see themselves and to be seen, how they wanted to designate themselves and to be designated. There were strong hopes for change, so they had to think about it themselves before others did so. They sought to be the protagonists of their own lives.

Following Teresa de Lauretis, I believe that the construction of subjectivity starts from the intersection and interaction of distinct axes of differentiation such as class, race, ethnicity, sexuality, age group, and so on. Each has a mode of action about which de Lauretis has reflected at length; she maintains, “These axes are thus considered parallel or of similar value although with a varying ‘priority’ according to each woman. For some, the racial axis has priority over the sexual axis when it comes to defining identity and the material base of subjectivity; for other women, the sexual axis has priority; for others, the ethno-cultural axis might have priority at a given moment.”20 With that in mind, it is not a minor detail that the workshops proposed by Sikos, Mizrahi, and D’Amico—or by each of them independently—were well attended. There was a need to think about subjectivity, to review it and reinscribe it, to give voice to those latent desires and to be the protagonist of one’s own life, leaving aside the bondage of mandates. Perhaps various factors converged that generated an environment favorable to such a situation: the end of a genocidal dictatorial regime and with serious consequences for social ties, the maturity reached by local feminist movements, and the genuine need for women to socialize, to recover physical and emotional communication, were some of them.

In this context, D’Amico’s relationship with Mizrahi boosted those needs for self-knowledge and reflection about lesbian desire. For that, they made use of photographic images that criticized the construct of a fixed and stable identity, creating a series of photo-performative works that were new to the local artistic scene.

Alicia D’Amico and Liliana Mizrahi: Reflections on Female Identity

During this process, Alicia was registering the vicissitudes of the workshop. Alicia acquired a certain invisibility, so that her activity with the camera didn’t bother anyone, nor was it taken into account, such was her discretion and the silence of her Leica. Alicia’s movement, therefore, did not affect the participants’ concentration on what I was explaining and proposing to them.

—Liliana Mizrahi21

In the 1970s the psychologist Mizrahi had traveled to Big Sur, in California, with the aim of taking some workshops at Esalen, center of the “human potential movement.”22 There she learned about their methodology through workshops based in psychology, which she adapted to suit her interests. In addition, she studied literature with Santiago Kovadloff, theater with Alberto Ure, and psychodrama with Eduardo Tato Pavlovsky, Argentine cultural referents in the latter half of the twentieth century. Not yet familiar with feminism, on neither a national nor an international level, Mizrahi was unaware of the feminist performance workshops led by Judy Chicago at Fresno State College and California Institute of the Arts. At that moment, her interests were focused on psychology.

Nonetheless, in the 1980s, at Lugar de Mujer, Mizrahi began to apply her knowledge about experimenting through workshops to different subjects, always with the goal that women should reflect on their own lives. Here she did connect her psychological training, her interest in theater and writing, with the knowledge she had then of feminism.

In the workshops, Mizrahi handed out notebooks so that the participants would keep a record of what they were doing and feeling. The prominence given to introspection led them to think about the proposed theme of analysis and their lives—whether it had to do with identity, changes, love, or violence, the idea was to think about how these had affected their lives. Then the workshop addressed the personification of the theme by the participants, using various objects and clothing that they chose freely. The experience closed with a photographic image of this staging that clearly showed how the women looked at themselves and the feelings that these set off, and there were discussions among them all together.

According to Mizrahi, “The non-awareness of oppression transforms the submission into the protagonist of a sterile life in the process of change.”23 In accordance with this, in April 1984 she gave the workshop “Identidad femenina: Imagen y cambio” (Female identity: Image and change), which was announced with a brief explanation in the Lugar de Mujer newsletter: “No image is innocent. Personal photography is loaded with conscious and unconscious ideological meanings that multiply. We are trying to open a channel of investigation through the photographic image and the word, taking as an axis the theme of change (three meetings).”24 That proposal was replicated in Bogotá, Colombia, during June of the same year, in the context of the I Encuentro Regional sobre la Salud de la Mujer (First Regional Encounter on Women’s Health).

Before starting any workshop, Mizrahi suggested that whoever might be interested meet to communicate what the experience would consist of. In that moment, the psychological process of working on themselves was already set loose in the participants. The next day, the experience began; first, there was a warm-up where each person introduced herself, and Mizrahi spoke about the importance of constructing an identity for oneself based on each person’s exploration. Then, she presented the psychosocial chronogram, which consisted of recording by decades the most salient facts in each participant’s life, in relation to national and international events. This exercise included Mizrahi and D’Amico as well, who did their own charts.

Next, the participants did relaxation exercises to prepare themselves for the photos. For that they selected some element or object that might identify them, ones they brought in or others supplied by Mizrahi and D’Amico.

From the photographic documentation on this workshop, I want to highlight the photo of a woman hugging a toy and with a tiny suitcase at her side. As if her image had been desperately fixed at this moment in her life, the woman clings energetically to the toy. Her hair hangs over most of her body. The photographic framing accentuates the dramatic burden of the position adopted by the figure. We know nothing about the protagonist of the image, but in the posttraumatic context of the end of the military dictatorship, the objects symbolize the fact that people were forced to escape to save their lives. Nonetheless, the solitude surrounding her would seem to insinuate the loss of loved ones, judging only from the object that she clings to.

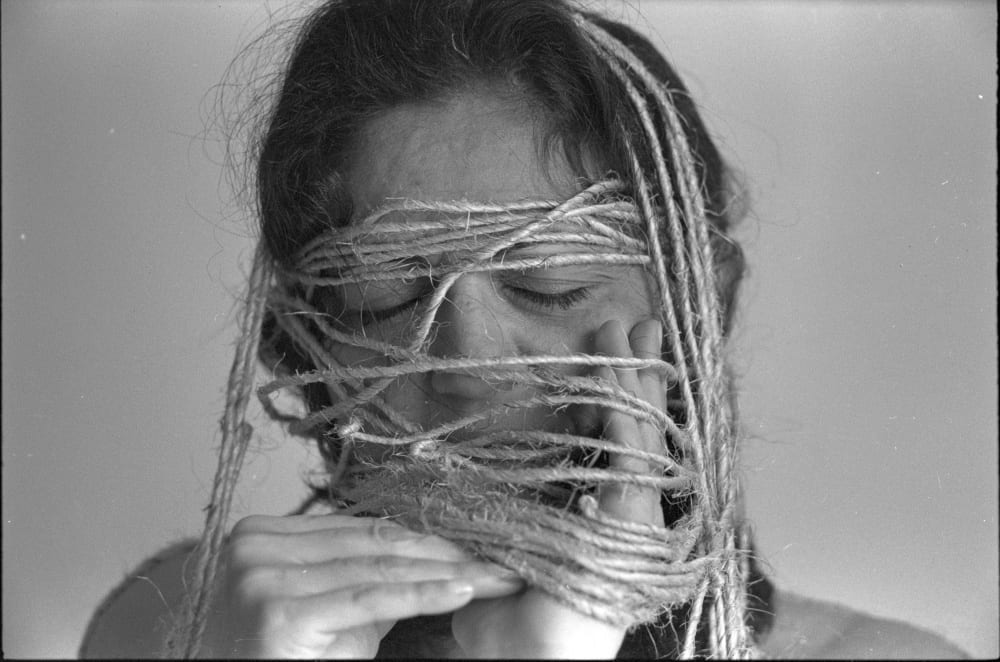

In September of that same year, and with a similar methodology, Mizrahi and D’Amico gave the workshop “A través de la imagen fotográfica y la palabra, mujer y violencia” (Through the photographic image and the word, women and violence). They explained, “It’s about developing our sensitivity to and consciousness of power and aggression in their distinct manifestations.”25

The coup d’état had marked the country with every form of violence imaginable. The recent advent of democracy enabled the possibility of speaking about these themes, which, without a doubt, were steeped in gender. As they already had done with “Imagen y cambio,” Mizrahi and D’Amico tested out the subject of the workshop first on themselves before directing the group. That is how the theatralization of violence resulted in a series of photos that reflected a performance by Mizrahi in which she used sisal twine. Mizrahi relates, “These photos are preparatory for the women and violence workshop. That is, we were working on the design I had done of women and violence, I was acting and these photos came out. I remember that each photo series we did with Alicia took an entire day.”26

Helped by D’Amico, she began to wrap her torso, her hands, and her face with the twine. The result was a series of seven photo-performances in which Mizrahi appears tied up. Her hand seeks to escape the restraint, though her eyes and her mouth remain obstructed. Her nose barely pokes out between the threads to allow her to breathe. The framing focuses on the twine that restricts, conditions the figure, and oppresses her to the point of objectifying her. “I multiplied the violence in the photo. I bought a roll of sisal twine to do something, I didn’t know very well what, the characters sprung forth at that moment. Here this came out. Alicia let me do as I wanted, she didn’t participate at all in my characters. She placed me in different poses for the photographs, thought about the light, the framing, she kept moving me until she got a point of view that convinced her, that she liked.”27

Although the tied-up face was a theme of some 1970s feminist artists, who sought to reflect on the body in relation to identity—as in the performances by the Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña (Santiago de Chile, 1948), particularly Tied Face (1970) and Tied Face (Life and Death) (1970)—Mizrahi and D’Amico’s works pose other questions.

In a first reading, steeped in the posttraumatic moment that Argentina was experiencing, the performance brings back the memory of certain methodologies of kidnapping and torture implemented during the state terrorism. According to Silvia Marrube, the body-torture relation was very present in Argentine creators of the democratic transition and was amply worked on by artists like Mildred Burton (b. Entre Ríos, 1942–2008), Alicia Carletti (b. Buenos Aires, 1946), Diana Dowek (b. Buenos Aires, 1942), and Ana Eckell (b. Buenos Aires, 1947).28 For that reason the Argentine context makes possible other interpretations, which lead to a distinction from performances and photo-performances done by artists from other continents, as in those by the German artist Annegret Soltau (b. Lüneburg, Germany, 1946), Selbst (1975) or Permanente Demonstration am. 19.1.1976 (1976), in which she reflects on the construction of identity and on subjectivity. The artist used sewing thread to tightly bind her body, mainly her face and torso, concentrating on her eyes, until they were covered completely. Although there is a reflection on self-representation in her work, the artist seems rather to focus her analysis on the limits of her body.

In D’Amico and Mizrahi’s photo-performances, we find a clear allusion to the violence, and the body tied up recalls the period of kidnapping during the de facto government. Nonetheless we must not forget that the kidnapped women suffered a type of torture that was different due to gender: systematic rape was frequent, along with the fact that many of them gave birth in captivity. That’s why this sort of image has other connotations within the Argentine context.

Still, we can also do a second reading, based on Mizrahi’s biography. Around that time she was beginning to question the system of obligatory heterosexuality, allowing herself to feel and live the desire for a woman. Leaving those bonds determined by the system of compulsive heteronormativity, breaking with the mandates of gender, was no easy task, and perhaps she was personifying these changes in her life.

My hypothesis is that the threads crossing the protagonist’s body symbolize the coercive barriers that condition desire. Although Mizrahi and D’Amico reflect on violence, they are also reflecting on desire.

The philosopher Judith Butler, who proposes to continue with de Beauvoir’s claim in The Second Sex, points out, “Beauvoir firmly maintains that one ‘comes to be’ a woman, but always under the cultural obligation of doing so. And it’s clear that that obligation does not create ‘sex’ in her. In her study there is nothing to assure that the ‘person’ who becomes a woman is obligatorily of the female sex.”29 Monique Wittig, in her novel Les Guérillères (1969), went deeper into the woman construct, showing how nothing indicates that the person who becomes a woman desires a man, since she can desire another woman.30

Already in the workshop, women spoke about the place that violence occupied in their personal lives. Through dramatizations, they shared among them that the personal is political. One of the participants revealed that she felt tugged on every day, trapped by the roles she had to fulfill and by the people who demanded her to do things all the time. These facts generated violence in her. For the discussion, the same protagonist proposed her companions should tug on her. That’s how they started to stalk her, wrapping her in hands that wouldn’t let her free. In that way, what she felt was dramatized. This formed part of role playing, which, following psychodramatic techniques, the women put into practice.

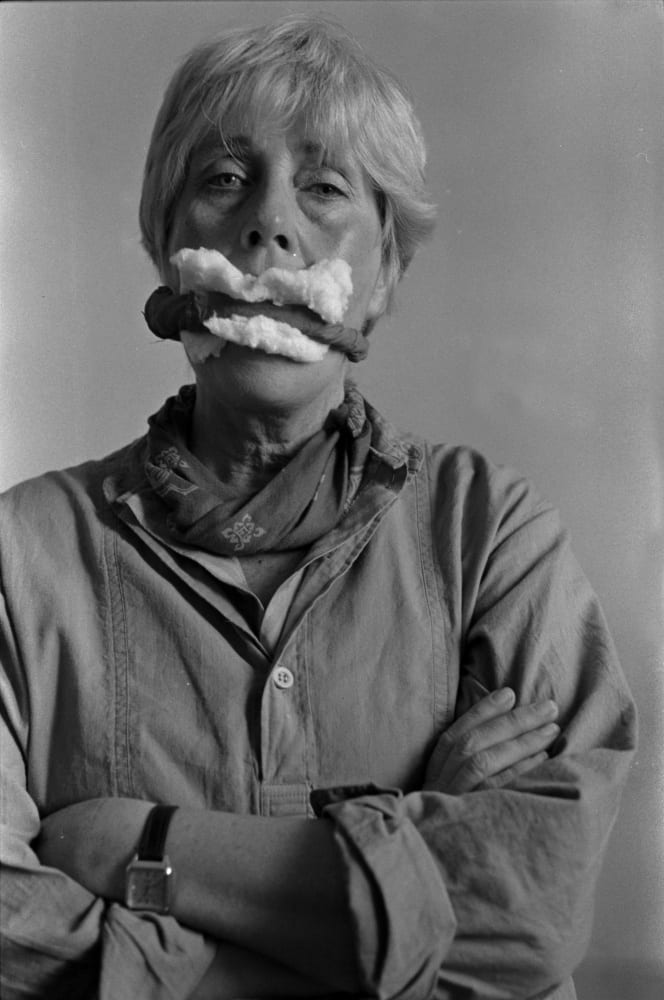

Ilse Fusková, the photographer and feminist activist, personified the violence itself, nullifying her mouth with cotton and covering it with a handkerchief wound up like a rope. It may be interesting to connect that photo with some facts about Fusková, who at the time had not yet come out as lesbian, but did so a year after D’Amico took this image. We can thus interpret that obstructed mouth as the silence in which she still carried her lesbianism. Nonetheless, years later, when the photo was published on the cover of the feminist journal Feminaria, that image as I understand it took on new meaning, coming to symbolize the silencing of lesbians within the very movements of local women, something I will discuss a little further.31

Bare Feet: The Political Visibility of Lesbian Desire

I have stated that two women, not one, make a lesbian. I was not thinking solely of the object of choice, but of the fact that lesbianism is a sexual practice as much as a particular structuring of desire.

—Teresa de Lauretis32

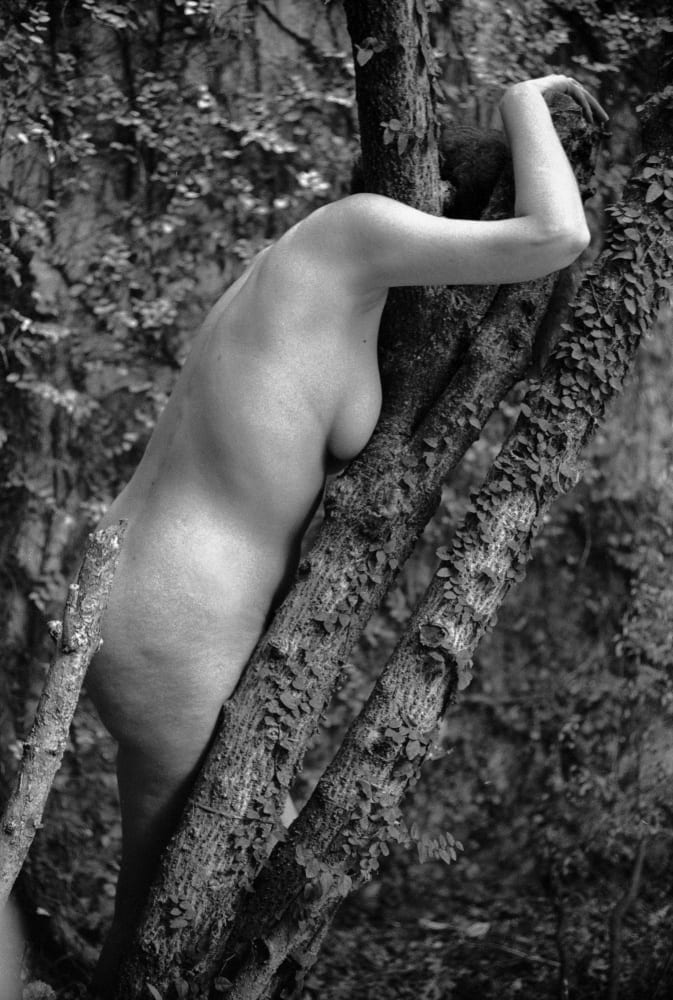

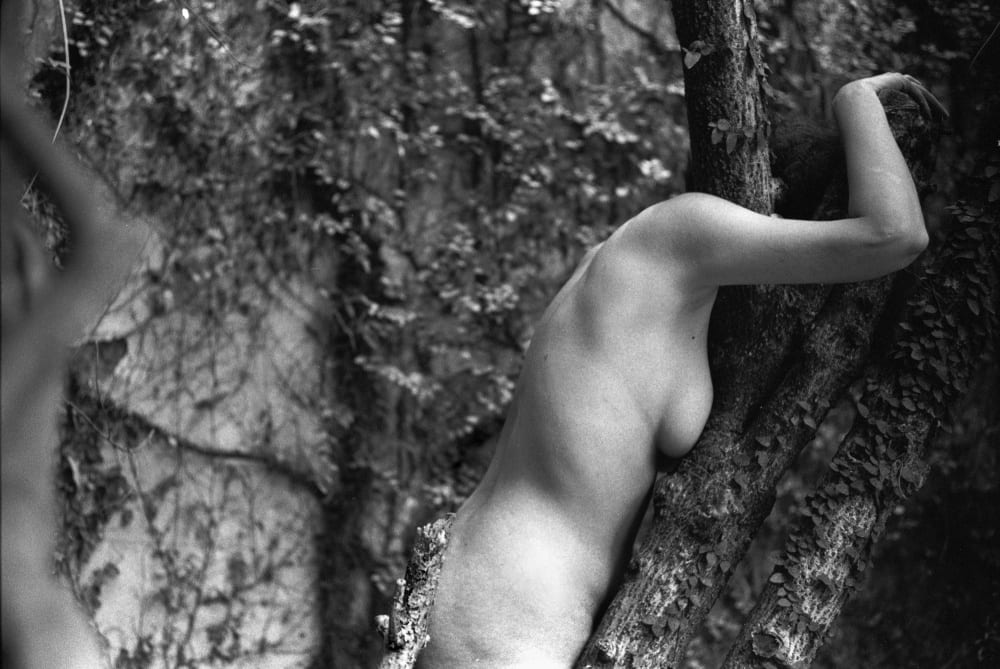

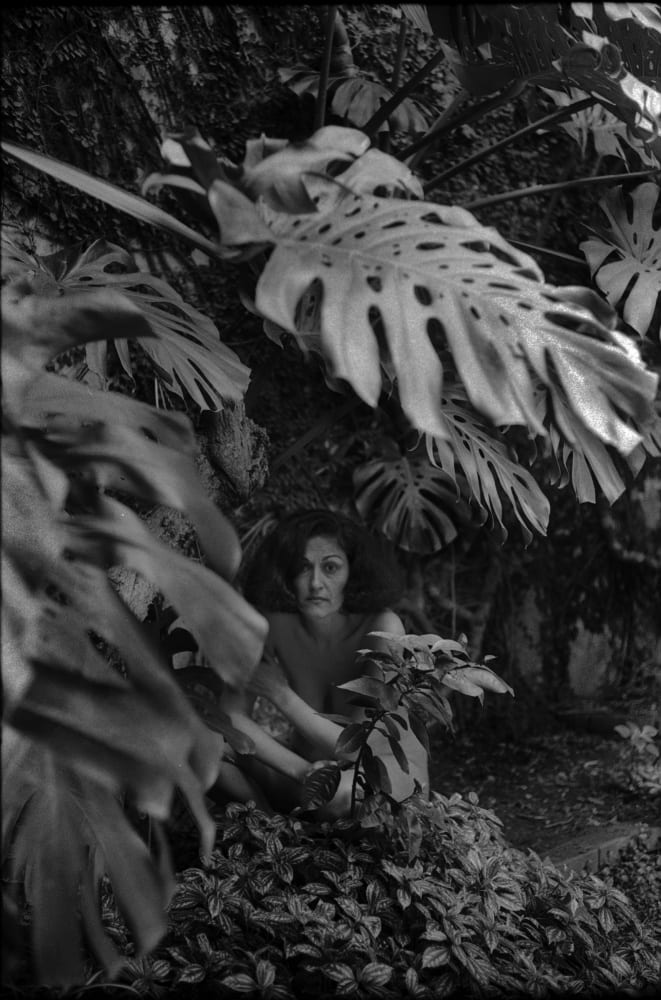

In 1985 D’Amico produced the series Pies desnudos (Bare feet), made up of twenty-six photos of Mizrahi interacting with nature in the garden of her house. While she moved around assuming poses, seeking to imitate the vegetation, D’Amico photographed her. The camera lens lingered on different areas of her body, seeking a sensuality different from that established by the male gaze, from which female visual representations have usually been constructed.

While Mizrahi moved through nature, D’Amico was capturing the silkiness of her skin in subtle contrast to the bark of the trees. Her hair was hidden amid the foliage. Her torso imitated the tree trunks. The roundnesses of the female body sought a delicate symbiosis with the vegetation.

The increased contrast in the photos that show Mizrahi stretching over the tree limbs simplifies the forms and emphasizes the textures. The framing acts in a passive way since it marks the limits the image can reach while directing the gaze toward a body with mysterious and sensual forms. The woman hides her face as she stretches out over the foliage. Like one more fruit, ample and voluptuous, she seems to form part of the tree. Areas in the background are in soft focus, as if the image had to do with a lost and distant paradise; we don’t know where the space begins and where it ends. Time pauses on that body-fruit, suggestive, sensual, unattainable.

This series was contemporaneous with the photographic production of Tee Corinne (b. Saint Petersburg, Florida, 1943–2006), who developed an extensive investigation into lesbian identity and desire. Nonetheless, unlike Corinne, who in series like Yantras of Womenlove (1982) experimented with photo montage, solarization, and various techniques with which she sought to protect the identity of her models, D’Amico focused openly on Mizrahi’s body and face. She captured her sensuality, without concealing a certain desire and enchantment toward the one who was her partner at the time. Her desire circulates through the selection of the framing, the light, the shadows.

D’Amico wrote in 1986 about a series of female nudes that she had started. She talked about it for the American journal Women of Power:

These images form part of a photographic series on female couples, a theme that has practically not been touched in Argentine photography. The models are not professionals, but couples in real life. I think it’s the only way to take up the theme, so that it doesn’t lose tenderness or authenticity. Only one of the photos has been published, in small format, by a photography journal, given the difficulties we run into thanks to a hypocritical morality that allows rapes, violence, and murder in the media but does not accept the reality of minorities. I think minorities are simply that: minorities who form part of a whole and who contribute to the totality of the human species. Human existence is unthinkable without diversity and that is precisely its richness.33

D’Amico proposed to study the circulation of female desire and its representation in images unmediated by male constructions, that is, by the imaginary of male desire.34 How was one to construct images that represented lesbian desire? Should lesbian desire open up a different visual repertoire? Is such a representation a way of subverting the heteronormative visual imaginary?

My working hypothesis is that D’Amico was certain that lesbian desire should and could constitute a visual imaginary that would account for sexual diversity. That’s why she doesn’t want models posing, but rather the circulation of a genuine desire that showed the historical difference of lesbians. That would account for their existence. I maintain that the series of photos Pies desnudos was a photo-performative exercise that reflected on lesbian desire, one year before she began a series depicting nude couples.

On an international level, lesbianism remained in the margins of artistic practice and discourse until practically the 1970s, when voices emerged that demanded rights for lesbians. Laura Cottingham points out: “It’s not surprising that the history of lesbianism emerged in academic studies only as recently as 1970, after which lesbians, apparently for the first time in history, are seen as a group and, thus, as people who could have their own history.”35 It’s important to highlight that in the United States, in 1977, thanks to the American art historian Arlene Raven (b. Baltimore, Maryland, 1944–2006), the Lesbian Art Project (LAP) was established, a collective that was devoted as much to creation as to research on lesbian artists and art history. In that regard, Terry Wolverton notes, “At an early meeting of LAP, Arlene had observed that, as a collective, we needed to use our own lives as material for research, our own experiences as lesbians for the configuration of our theory. We accepted the premise since we were well versed in the notion that ‘the personal is political.’”36 It was then that artists investigated the particularities of lesbian desire through various performances and the experimental theater piece Femina: An IntraSpace Voyage (1978), among other works.

Nonetheless, we cannot maintain that in Argentina these experiences were known. On the contrary, D’Amico’s research on the body and lesbian desire co-incided with the claims of invisibility that this group suffered within Argentine feminism and, particularly, at Lugar de Mujer. On the one hand, there did exist a formal, theoretical acceptance for the inclusion of lesbianism within feminism, but in fact that didn’t actually happen. Lesbianism was not discussed at Lugar de Mujer until solitary voices started to come forth who raised the question. In 1984 the poet Hilda Rais had declared the right of lesbians to a voice of their own, only to be met with silence. Thus, in a long letter she notes, “Let’s not practice violence among ourselves, perpetuating another imposed division, the enemy is the same and oppresses us in various ways. Our work is to be the subject of our lives and to struggle together until it’s no longer necessary to enunciate an identity based on sexual preference, until feminism is no longer necessary.”37 Between 1986 and 1989 the Grupo de Reflexión Lesbiana met at Lugar de Mujer, directing workshops and publishing a newsletter called Codo a Codo (Elbow to elbow).

Although the silencing of lesbians was happening in the consciousness-raising groups of the 1970s, their legacy was strong for feminists of the 1980s and made it clear that the possibility of giving themselves and the world new meaning would not come about through solitary action but through relationships with others.38 Now was the moment.

I find various coincidences between the decade of the 1980s and the timid discussions, if you like, about feminism, subjectivity, and sexual identities offered in Argentina, with respect to those that took place within North American and European feminism. Argentina counted on a plurality of positions that made coexistence possible between lesbian radicals and lesbian feminists working together. In 1988, for example, the Cuadernos de Existencia Lesbiana (Notebooks of lesbian existence) appeared for the first time, a publication that reflected the need for this group to start writing its own history. There, various texts were translated and published, by Susan Sontag, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, Kate Millet, Simone Weil, Charlotte Bunch—whom Ilse Fusková interviewed years later39—Mary Daly, and Judy Grahn, among other foreign authors. They also made room for testimonies by Argentine lesbians and for the literature of women writers like María Moreno, Alejandra Pizarnik, and Cecilia Vicuña. Richly illustrated with collages by the artist Josefina Quesada and photographs or caricatures with a feminist tone chosen by Fusková, Claudina Marek, and Adriana Carrasco, the Cuadernos de Existencia Lesbiana constituted a way of showing the wealth of gazes within Argentine lesbianism.

In this context, and coinciding with D’Amico’s research, we can situate the photographic series S/T produced by Fusková and the group of women from Cuadernos. It is made up of five photos that show a lesbian couple painting their bodies with menstrual blood. The models develop scenes that share in both ritual and festive aspects, seeking to break with the patriarchal image of sexual practice between lesbians. Added to that was Fusková’s interest in claiming menstrual blood as an energetic fluid, charged with life, contrary to the historical idea of dirtiness and filth that must be hidden.40

We can observe, then, that in the early 1980s the genre of the photographic nude allowed D’Amico to create a visual repertoire that showed new research on identities and desires that had been historically made invisible. As Mizrahi notes, “We seek to recognize the desire, to point it out and legitimize it for what it is: a legitimate desire.”41

Together the two women brought forth a series of factors that facilitated these searches: an important feminist education that made them knowledgeable about thinkers like de Beauvoir, de Lauretis, and Rich, to which were added their different artistic formations and D’Amico’s serious professionalism as a photographer. Taking on the particular structuring of desire in circulation between them—paraphrasing de Lauretis—motivated the investigation into its representation.

Nonetheless, the possibility of representing themselves came after the decision to name themselves, to recognize themselves. That’s why I emphasize the struggles that took place between lesbians and feminists for recognition of the former. A voice of their own brings with it the configuration of a visual imaginary that bore witness to other forms of desire. That said, I do not adhere to the idea that there’s just one kind of lesbian desire nor that there’s only one way of representing it. Following Judith Butler, I speak of lesbianism in order to “make use of a category that is aware of what it excludes.”42 The representation of lesbian desire is as pluralistic as lesbians who represent it.

In a photograph in which Mizrahi leans against the enormous trunk of a palm tree, also in the series Pies desnudos, D’Amico contrasts the voluptuous and round forms of the woman’s body with the prickliness of the tree trunk. The visual axis is traversed by a diagonal that reaches from the little cat to the large body of the woman, passing through the trunk that lends support as an intermediary, thus contrasting forms and textures: the silkiness of the animal’s skin and the woman’s skin set against the roughness of the tree trunk, the little round body of the cat that seems to replicate in an opposite way Mizrahi’s belly. That play of roundnesses and zigzags weaves together the compositional universe of the photo. Nonetheless, it is all concentrated in a close-up that restricts our vision in depth while it also summons a lost Eden, a paradise on earth.

In the close-up photograph, Mizrahi seeks to cover her body with the vegetation that climbs up her legs as if it were clothing. The framing causes that mysterious body to emerge from the darkness of the background, where she is almost hidden amid so much nature. The light leads our gaze toward the center of the work. The vegetation warmly wraps the roundnesses of a female body that the light is discovering.

D’Amico’s framing leads our gaze toward Mizrahi’s body, body-fruit, vegetation-body. All are modes of representation of a desire that, as such, is slippery, performative, labile. Mizrahi’s eyes are directed toward the viewer and seem to tell us that there are possibilities for representation of what the heteronormative system excludes, that those exclusions have a history and an influence on the future.

In this series we can find a reinscription of the female imaginary marked by lesbian desire. In that act, D’Amico turns the photos into counterimages, excessive, hyperbolic, provocative, passionate, seeking a reinvention of the erotic and of love.

D’Amico’s photographs inscribe these images into a visual genealogy of desires materialized in bodies—and of political bodies and desires.

Throughout the 1980s in Buenos Aires, we witnessed the development of important debates about female identity and lesbian desire that took into account the moment our feminist groups were then experiencing. The Lugar de Mujer was a platform that connected feminists from the 1970s with women who were uneasy and beginning to feel the need to live by the lights of their own desires. There, militants met with women exiles who were slowly returning to the country after the dictatorship, curious young women, mature women, professionals, and housewives. Such diversity was inscribed in a context of democratic effervescence and recuperation of freedoms, which included sexual aspects, meaning, and the struggle for equal rights. Feminist activists took to the streets to keep fighting for unresolved causes from the 1970s: abortion, equal custody of children, and equal pay for the same work, among other things. And on top of that, there were also the sexual dissidents. So, in the late 1980s the lesbian collective launched its claim for a history of its own with Cuadernos de Existencia Lesbiana and with groups that met to discuss the issues that led to Lugar de Mujer.

This context was the catalyst for D’Amico’s research into images of women, desire and identity, which began to solidify around 1982. For D’Amico, the photographic portrait was a fundamental tool with which to take apart the visual framework that crystallized around women in social and domestic mandates, ideas about beauty, and more. Confronting a woman with her own image could lead to questioning the hetero designation, understanding by that the delimitation of an identity imposed from outside onto the subject.

In this search to disassemble the visual field of the compulsive heteronormative system, D’Amico delved into the genre of the portrait, broadening its limits and exploring other methodologies to approach it. She used it as a feminist instrument so that women could reflect on their identities.

She drew on the contribution of two psychologists—Sikos and Mizrahi—with whom she worked in the modality of the workshop, developing reflective and creative games, disrupting mandates. One of the main objectives was to get women to construct their own images and articulate what they felt while looking at themselves. In those workshops female authority was created, valuing the legitimacy of feelings, reactions, and desire itself. The participants worked directly with subjectivity to reach what D’Amico called woman truth, that is, a woman whose image reflected her desires, her personal choices, that which she felt she was.

Nonetheless, that research gave rise to other questions that motivated further analysis of lesbian desire. D’Amico used the genre of the nude to show a desire made invisible in its revulsion at the heteronormative system. Labile and slippery, that desire runs through the series Pies desnudos, the photo-performances she did with Mizrahi.

Photography thus turned into a political weapon, reflecting personal universes that shook up normative constructions.

Photography was, for D’Amico, the language chosen for her feminist activism.

Photography was her political tongue.

María Laura Rosa holds a PhD in contemporary art from the UNED (Madrid) and a degree in art history from the Universidad Complutense (Madrid). Currently, she is a professor at the Universidad de Buenos Aires and a researcher at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in Buenos Aires. Her research focuses on feminist art, gender, and politics from the 1970s through today. She has published Compartir el Mundo: La experiencia de las mujeres y el arte (2017) and Legados de libertad: El arte feminista en la efervescencia democrática (Biblios, 2014).

- Alicia D’Amico, “Estética y Feminismo,” unpublished manuscript, ca. 1986, Archivo Alicia D’Amico, Buenos Aires. ↩

- I speak of “inner exile” (insilio) to refer to silencing or isolation within one’s own country. ↩

- Among its founders were Marta Miguelez, Hilda Rais, Alicia D’Amico, María Luisa Lerer, María Luisa Bemberg, Sara Torres, Graciela Sikos, Lidia Marticorena, Ana Amado, and others. ↩

- “¡Casa Tomada! Un lugar para cada una y cada una en su lugar,” Tiempo Argentino, August 13, 1983, “Women” section. ↩

- D’Amico in brochure for photographic exhibition Creation of Her Own Image, May 13–20, 1985, Archivo Alicia D’Amico, Buenos Aires. ↩

- “Manifiesto de la Unión Feminista Argentina: Luchas por la reivindicación de las mujeres,” La Opinión, April 23, 1972. Leonor Calvera, a member of UFA, later explained, “The term ‘new woman’ had to do with our concessions to the Left. In the 1970s, the Left proposed that urgent change was needed for the development of a new man. Others spoke of a new world. Everything remained to be done. That’s why we proposed the new woman, winking to the Left by way of the terms we were using.” Calvera, interview with the author, August 15, 2010. ↩

- “Manifiesto de la Unión Feminista Argentina.” ↩

- D’Amico in brochure for photographic exhibition. ↩

- Mayra Leciñana, interview with the author, Buenos Aires, January, 15 2016. ↩

- “Alicia D’Amico: Luz natural a las mujeres,” Tiempo Argentino, March 15, 1983, “Women” section. ↩

- “Only feminist revolution can fully eliminate the sexual schism causing those cultural distortions. . . . The incorporation of the abandoned half of human experience—the female experience—into the body of the culture in order to create an inclusive whole is only the first step, a precondition. But the schism of reality itself must be removed first, so that there can be a real cultural revolution.” Shulamith Firestone, “(Male) Culture,” in The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (London: Women’s Press, 1979), 148–60, rep. Feminism-Art-Theory: An Anthology 1968–2000, ed. Hilary Robinson (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2001), 13–17; 16. ↩

- Leonor Calvera, El género mujer (Buenos Aires: Editorial de Belgrano, 1982). ↩

- Ilse Fusková, Silvia Schmid, and Claudina Marek, Amor de mujeres: El lesbianismo en la Argentina hoy (Buenos Aires: Planeta, 1994), 42–43. ↩

- Graciela Sikos, interview with the author, Buenos Aires, September 22, 2016. ↩

- Mayra Leciñana, interview with the author, Buenos Aires, January 15, 2016. ↩

- Facio also wrote, “The female gaze can become a boomerang. Forgetting the version everyone else expects, various women attempt their first photographic self-portraits and learn to recognize their true image or to change it.” Sara Facio, Tiempo Argentino, August 13, 1983, “Women” section. ↩

- For more information about alfonsina magazine, see Paula Bertúa and Lucía De Leone, “Identidades textuales y autorales en alfonsina: Un juego de representaciones,” presentation at XXIII Jornadas de Investigación del Instituto de Literatura Hispanoamericana, Buenos Aires, 2009. ↩

- Alicia D’Amico, “Cómo Somos,” alfonsina, no. 3 (January 12, 1984): 8. ↩

- Alicia D’Amico, “Salud, identidad y socialización: Relaciones con la imagen fotográfica,” in ¡Es preciso volar! Primer Encuentro Regional sobre la Salud de la Mujer (Bogotá: Ministerio de Salud, 1984), 52. ↩

- Teresa de Lauretis, “Sujetos excéntricos,” in Diferencias: Etapas de un camino a través del feminismo (Madrid: Horas y horas, 2000), 111–52, 132. ↩

- Liliana Mizrahi, interview with the author, May 18, 2016. ↩

- Esalen was founded in 1962 by Michael Murphy and Dick Price, who were inspired by the psychology of Abraham Maslow to create a space dedicated to the human potential movement. Today it continues to offer workshops and other activities. See www.esalen.org/, as of January 29, 2019. ↩

- Liliana Mizrahi, La mujer transgresora: Acerca del cambio y la ambivalencia, 6th ed. (Buenos Aires: Emece, 1991), 101. ↩

- Lugar de Mujer, newsletter, April 1984, Archivo Marta Miguelez. ↩

- Lugar de Mujer, newsletter, September 1984, Archivo Marta Miguelez. ↩

- Liliana Mizrahi, interview with the author, Buenos Aires, September 13, 2016. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- For more information, see Silvia Marrube, “Violencia de Estado y vida cotidiana: La obra de Diana Dowek, Mildred Burton y Alicia Carletti entre 1974 y 1981″ (master’s thesis, unpublished, Instituto de Altos Estudios Sociales, Universidad de General San Martin, 2012). ↩

- Judith Butler, El género en disputa: El feminismo y la subversión de la identidad, trans. María Antonia Muñoz (Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2007), 57. ↩

- Monique Wittig, Las Guerrilleras, trans. Josep Elias and Juan Viñoly (Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1971). ↩

- See María Laura Rosa, Legados de libertad: El arte feminista en la efervescencia democrática (Buenos Aires: Biblos, 2014). ↩

- Teresa de Lauretis, The Practice of Love: Lesbian Sexuality and Perverse Desire (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 155–77; 171. ↩

- Alicia D’Amico, unpublished text written for Women of Power, 1986, Archivo Alicia D’Amico, Buenos Aires. ↩

- A text that takes up this question from the perspectives of feminist art theory, psychoanalysis, and structuralism is Griselda Pollock, “Missing Women: Rethinking Early Thoughts on Images of Women” in The Critical Image: Essays on Contemporary Photography, ed. Carol Squiers (Seattle: Bay Press, 1990), 202–19. ↩

- Laura Cottingham, Seeing through the Seventies: Essays on Feminism and Art (Amsterdam: G+B Arts International, 2000), 181–82, italics in orig. ↩

- Terry Wolverton, Insurgent Muse: Life and Art at the Woman’s Building (San Francisco: City Lights, 2002), 61. ↩

- Hilda Rais, “Lesbianismo: Apuntes para una discusión feminista,” Travesías: Temas del debate feminista contemporáneo, October 1996, 137–42; 142. ↩

- The poet Hilda Rais notes in this regard, “If in a lesbian the fear of rejection, the fear of the other woman’s fear, already constituted part of the adaptation to a form of amputated life, we, as feminists who wanted to construct and broaden the movement, were caught in a dilemma. We were attacked, disqualified, from the Right, the Left, and the center with distinct and even opposite arguments. Yet they all coincided in the same anathema: lesbian-feminist.” Rais, “Desde nosotras mismas,” 21–24. ↩

- Fusková interviewed Bunch during the latter’s participation in V Encuentro Feminista Latinoamericano y del Caribe, which took place in San Bernardo, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, May 18–24, 1990. ↩

- See Rosa, Legados de libertad, 47–63. ↩

- Liliana Mizrahi, interview with the author, Buenos Aires, September 13, 2016. ↩

- Judith Butler, “Imitación e insubordinación de género,” Revista de Occidente, December 2000, 85–109; 86. ↩