Introduction

Luca M. Damiani, Getting to Know Hyperacusis. Poem, 2019. Read by the artist.

Getting to know hyperacusis

Acoustic disorder in my neurological system

Shaping sounds into painful background triggers.

A decreased tolerance

A higher sensorial sensitivity

A hacked auditory sense.

Clouding the day-by-day flow

Invisible in its quiet hidden action

Visible in its loud found disruption.

In parallel, the filtering and ringing tinnitus

Bilateral in its cutting and humming

Faulty in its neurosignaling.

As a whole, it is like a pattern of mathematical 2D functions

Creating the wrong flat computational results

And returning parameters of overloaded graphic limbo.

Here, I start to process it.

Here, I try to recode it.

Here, I aim to reframe it.

In this piece for Art Journal Open, I take a look at the hearing conditions of hyperacusis and tinnitus. I am a lecturer and media artist living with both of these auditory disorders, and in this art-essay I collect together some of my related artistic responses and interpretations. The digital art and written reflections I present here represent different phases of my artistic and reflective cognitive development, and illustrate how I explore hyperacusis as part of my artistic practice and scholarship.

My art practice is cross-disciplinary and cross-media. My background is in computer science, coding and technology, working in the arts, cultural sector and academia. In January 2018, I was working as a digital producer; due to faulty audio equipment, a large set of speakers blew right behind where I was standing, exposing me to an incredibly high-level sound blast. The blast was so powerful that it knocked me to my knees; I subsequently suffered vertigo, feeling faint and dizzy.

Over the following weeks this dizziness and fogginess continued daily, with a continuous high-pitched whistling in both ears that varied in intensity and pulsation. Visits, tests, and referrals to and from various doctors, clinicians, and hospital departments in the United Kingdom ensued in an attempt at reaching a diagnosis for my symptoms. Everyday life became harder and harder: being anywhere outside of the quiet of my own home (with calming background music) started to feel painful to my ears and brain; days were stressful and full of either overwhelming sensations of cloudiness and discomfort, or intense anxiety. And I was very, very tired, but unable to sleep.

Around five months after the accident, my hearing (which had suffered a significant loss from the blast) returned, accompanied by an increased level of sensitivity to sounds causing discomfort and muddling to my brain. I developed a low tolerance not just to high-pitched or high-volume noises, but to any place with multiple ambient sounds. This finally brought a diagnosis of not just the bilateral tinnitus, but of bilateral hyperacusis too, with both pain and vestibular hyperacusis types.

Hyperacusis is an auditory condition characterized by a high sensitivity or decreased tolerance to sounds;1 it is developed when the central auditory processing in the brain perceives noise in an amplified way, leading to pain, often extreme discomfort, and neurological overload. It is a relatively uncommon condition—estimates are that long term hyperacusis affects just one in 50,000 people.2 Its impacts can be considerable, including conditions of fatigue and negative impact on mental health.3 While research is ongoing, a definitive cause of the condition is not known, and hyperacusis often lasts indefinitely.

Tinnitus is a hearing disorder that consists of the perception of a constant or alternate noise (inside either or both ears) usually in the form of ringing, whistling, humming, or alternating pulsing (to name a few), coming from the inner brain with different levels of intensity and pitch.4 Compared to hyperacusis, it is a relatively common auditory disorder that has affected millions of people at some point in their lives. The brain tries to readjust to a level of sound it got used to, creating an additional noise to balance the missing auditory information; the neural plasticity of the brain seems to increase its spontaneous firing rates and synchrony among neurons in the central auditory structures, randomly generating the phantom sound.5 Again, while there are advancing technologies and therapies, plus a variety of organized support networks to help those with tinnitus, there is no straightforward treatment and no known cure for the condition. And, like hyperacusis, it often lasts indefinitely.

My tinnitus is continuous in both ears and takes the form of a variety of ringing, whistling, and humming noises. It often increases in volume, for short and intense periods of time, which can feel like a searing, stabbing pain within my ear through to my brain. My hyperacusis manifests as a combination of a variety of physical pain and vertigo which is bought on not only by high-volume and/or high-pitched sounds (e.g. siren, motorbike, ringing bell, dog barking, live music, etc.), but also when there are normal or multiple sounds (e.g. day-to-day noises, such as multiple people talking at the same time, distant traffic, cutlery on a plate, a door opening or closing, background music, a telephone ring, etc.).

Following my diagnosis, I began, in earnest, as much as my newfound levels of fatigue would allow, to investigate these conditions: other people’s experiences, support organizations and networks, and the various treatments, technologies, and therapies available, from hearing aids (which have been a lifesaver for my tinnitus) to the various different sound-filtering and noise-cancelling headphones available for purchase, sound therapies, mindfulness techniques, psychotherapy, and so on.

Hyperacusis has impacted my quality of life in every way. It is very difficult to tolerate sounds in the everyday—those that seem completely normal and are often unnoticeable to others. My everyday life, my work, home, relationships, and financial and social lives have all been affected, especially because it has made it very difficult to function in situations outside of my own home. Living in the urban environment of London became intolerable, and my artistic practice (which included travel to workshops, events, festivals, and installations) and my university teaching job were very difficult to maintain.

In addition, the level of the bilateral hyperacusis and severe tinnitus I developed has impacted my neurodivergent condition of Asperger’s, of which I have a high-functioning diagnosis.6 The reaction to enhanced sensory sensitivity has impacted my normal daily activities and my level of brain overload to external stimuli. This has required lots of additional medical interventions and psychological therapies in relation to this invisible sensorial disability.

My life has changed significantly, and I am now trying to readjust and reframe it. As a response to these changes, it felt appropriate and healthy—not to mention advantageous to stay active in my profession as much as my health allows—to use my artistic practice to look at and process my new circumstances, critically reflecting on it and using it to prompt an artistic response, allowing further self-awareness. This process also helps me to learn more about both conditions and their patterns, and so begin to learn how to cope with them better. So alongside undertaking a variety of sound therapies, mindfulness strategies, relaxation techniques, and cognitive therapy programs, I have begun to look at hyperacusis and tinnitus through a so-called art and design lens, using my artistic practice to express in a visual, visible way this new invisible but all-consuming experience of being. Art has the power to show or reveal the unseen and the mysterious and make something new with it that we can connect to, find some understanding—I want to do this in my practice.

It is important to note that this work has been created while actively living and learning how to deal with this acoustic disorder during its first year of impact in my life; it is a live and ongoing journey. This work allows me to share my own processing of this sensory experience while starting to learn how to cope through different sound therapies and cognitive behavioral therapies (also known as CBT, a technique that allows a learning and understanding of our reactions to our behavior, prompting mechanisms to cope with difficult situations).7 I started to use this process and the exercises as one of the tools for keeping track of and making records of my condition daily: recognizing and recording moments and reactions, and using this log of reactions to reveal recurring patterns. I began to form shapes out of these patterns, which I would then use in my artwork.

With my hyperacusis and tinnitus, I have created a variety of media-design outputs using artistic approaches and methods to connect to my experiences, reflecting and interpreting my neurological reactions to sounds and to the situations in which I experience them. I am interrogating the different and invisible interactions that hyperacusis and tinnitus bring, and collecting auto-ethnographic data each day, keeping a visual and written record or diary with sketches and notes.8

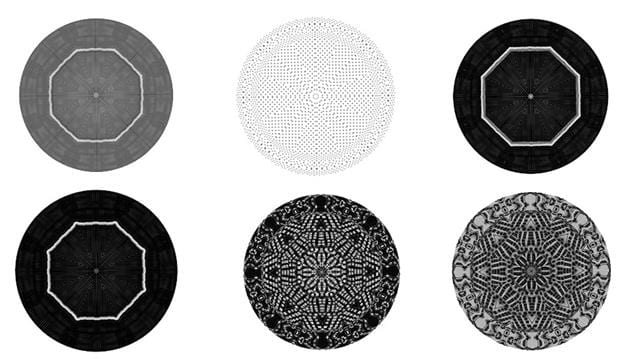

To identify patterns, I take these records and process the reflections of the experience of the different sounds into categories with codes and symbols; these then begin to create geometrical forms. These forms reveal patterns of moments and time. They act as visual interpretations of my responses and feelings of processing each sound, and show aspects of the physical and emotional reactions connected to them. 9 The following artworks show some of these processes and explorations.

Processing the Mind with Hyperacusis

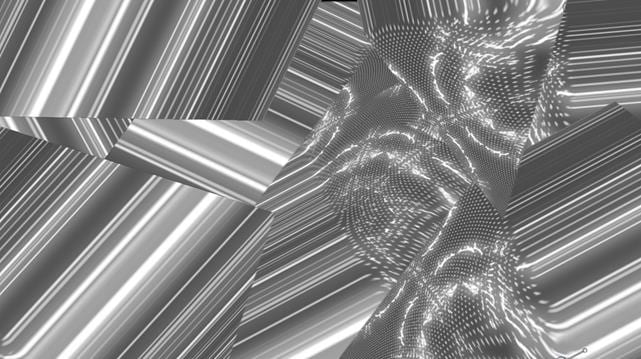

My Aspie with Tinnitus + Hyperacusis is a video in which I reflect on specific patterns of sound processing and related/connected responses. It was first created for a digital design installation and short paper Designing the Mind for the V&A Digital Design Weekend program in 2018.10 This piece was a means of learning more about the conditions, coping with related stressful situations, observing my reactions, and trying to look at everything objectively. The video explores how the action of sound affects the overload of the brain, and tries to reflect the speed of changing patterns. As hyperacusis builds up, an instinctual reaction is to cut sounds off with hearing protections, wearing sound-filtered earplugs, using additional sound-removal headphones, covering the ears in all possible ways. By doing this, however, tinnitus builds up with even more intensity. In addition, it is important to try to not overprotect the hearing; if this happens, one’s auditory senses can become even more sensitive. CBT techniques are useful at this point too: learning how to recognize moments, triggers, and reactions, and how to rationalize and define them in a more systematic and controlled way. With this piece I am visually recalling the sound experience but filtering it in silence, focusing on movement and imagining neuro reactions of the central nervous system.

Hyperacusis Hacks

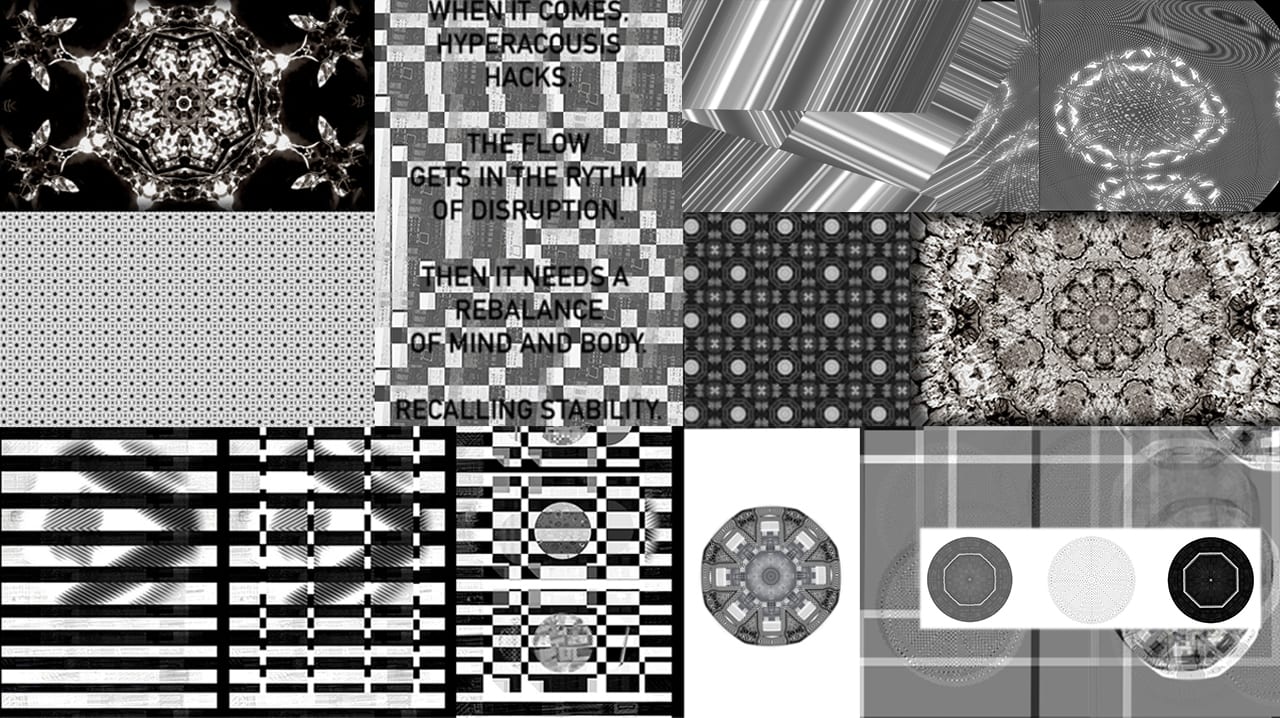

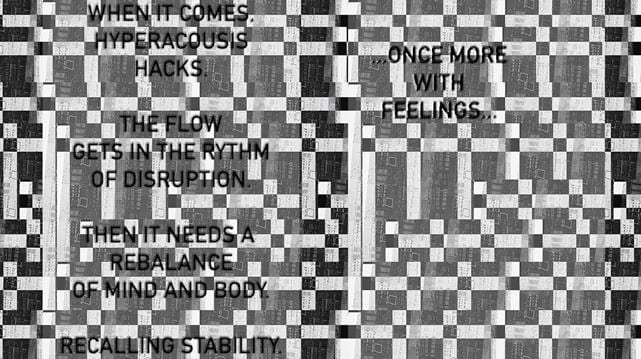

With hyperacusis, the different categories of time, reflection, thoughts, and balance get mixed up. As a visual response to that, here I compile a selection of the flows present in the neurological action of receiving sound, with the key element of disruption and disorder that hyperacusis brings. The different stages of thoughts are cross-connected and even mixed up, becoming a muddle of data and information (both external and internal), as hyperacusis creates an atmosphere that makes deciphering information overwhelming, causing overload in my mind. So, the “clearer” modes of structured perception and mental processing (always in the background) become harder to analyze and rationalize. The overload builds up, then the sensation becomes a repetitive channeled matter, that, in different stages, scales down, multiplies, reshapes, turns, scales up, remultiplies, disrupts, and segments itself.

In this visual piece, I work with these eight stages, creating a background of graphic data abstractions and related changes that creates the final still-image graphic above. The collected data is based on my personal notes and statistics from a CBT tool I use (psychological meters of reading of my mood flow) as well as numerical parameters of audiological exams. The development of visualization creates a relation between the graphics (abstracted numerical data) and the text (abstracted keywords of diary notes), and below I show a GIF with some of the stages of making.

Luca M. Damiani, Hyperacusis Hacks. GIF Animation of Processing Stages, 2018

My Brain Stress Overload

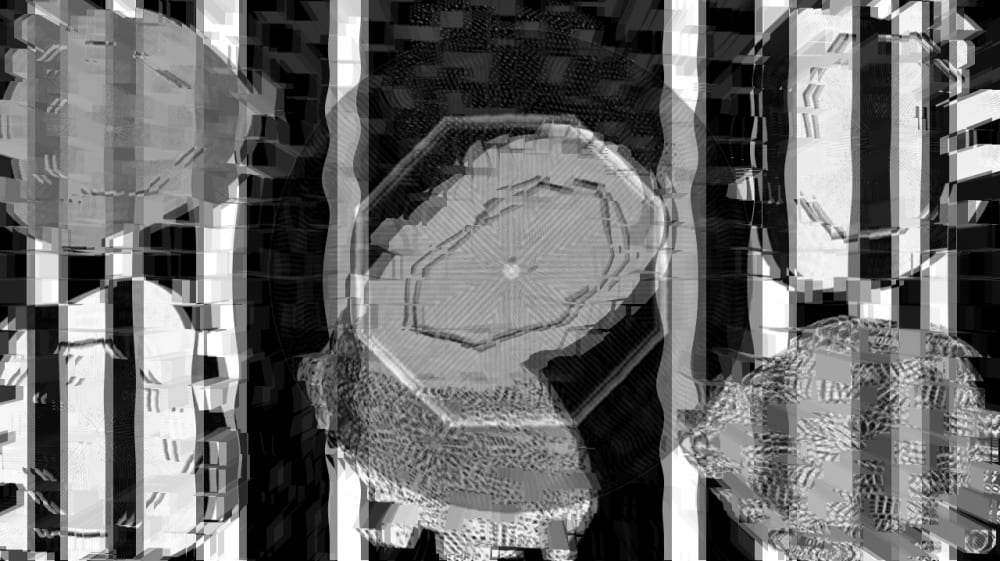

Having hyperacusis and severe tinnitus requires a constant readjustment of situations. In My BrainStress Overload, I try to visualize my reaction to a typical day at work (e,g. running a digital art lecture and workshop) and how that affected my mental response. This experience underlined the need for changes to be adopted in my working life, as I started to being unable to work in many of my previous jobs with the new cognitive overload present in the workspaces and environments.11

The session was run in a studio with bright lighting and multiple background sounds due to the twenty participants that were taking part in the workshop. The day started (and continued) with lots of theoretical inputs and discussions happening with a high level of immersion of the participants. Like in any creative workshop setting, there were lots of constant translations from focus to refocus, from listening to input, from reflection to questioning. Minute by minute and hour by hour (and every minute felt like an hour), recalling facial connections with others, absorbing the bright light from the ceiling, filtering the sounds of people talking or a pen clicking on the table or a chair moving or an airplane passing by, felt way too much—I experienced a neurological escalation of sensory overload. Even taking more breaks than usual and wearing hearing filters did not help avoid the overload. In this piece, I try to depict it. The overall artwork is divided in several stages; each stage represents moments of processing, moments of distress, moments of building-up, moments of overload, moments of channeling, moments of pain. I worked on this piece constructing and reconstructing a narrative that would connect to my own reflection of the brain focus, data processing, first overloads, refocus, and then up to higher overload mode. In this piece there is a visual segmenting concept that exaggerates the perspective of reality, shaping into a sensory adaptation of the surrounding, with final pixilation as a way of data becoming less clear, messages becoming less readable.

My Periscope of Still Life Tinnitus

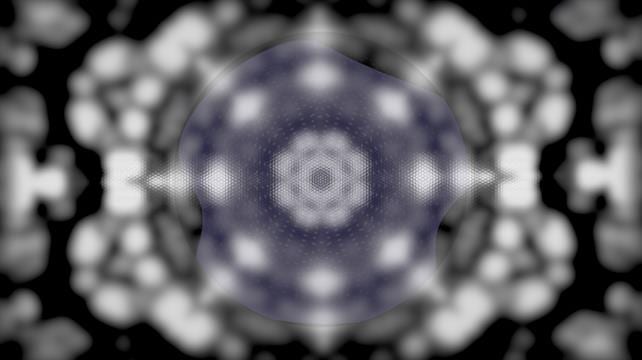

In My Periscope of Still Life Tinnitus, I try to visualize the constant multilayered action of tinnitus. It is like a still sound that is always present in the brain, bilateral in my hearing system, sometimes with higher pitch on the right, then on the left, then back to both. It is also a pulsation, a humming, a whistling, a ringing—a mix of all of these. Here I reflect on tinnitus as a neuro-animated graphic that feels like it is stopped despite its constant motion. Slow, but constant. A still-frame in the auditory system but with things moving in the surrounding cell, as an unplanned firing between neurons, acting as engines of sounds and amplifiers of tones. The texture recalls the materiality, the natural environment that is necessary to cope with a mapping of nature sounds such as wind, leaves, waves. These nature sounds are present in the hearing aids I use as part of the auditory desensitization process, creating a sound to act as masking to the severe tinnitus, as well as playing with the sensitivity of the hyperacusis.

In this piece I reflect a design of neuro activity but connected to a shading of molecular (through a periscope view) of leaves. The graphics aim to recollect the aspect of sound therapy, recalling the periscope as a tool and symbol of scientific observation and analyses. This brings different elements of cognitive reactions together, allowing an abstraction of the surrounding external inputs to the internal processing. A filtered and layered connection.

Signaling

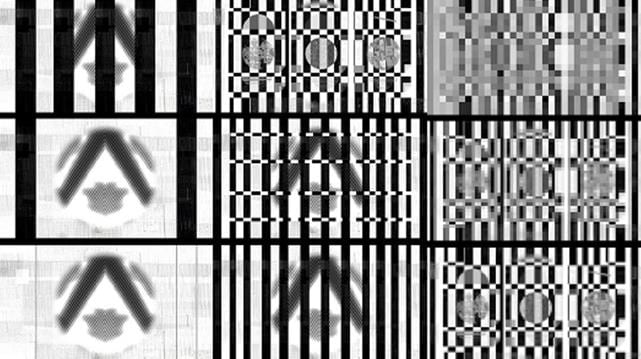

Balancing the rhythm of hyperacusis and different types of tinnitus can be challenging and requires a variety of methods to learn how to cope with it. Many small neurons are responsible for the processing of auditory information, decoding the signals for a brain reaction and a perception of sounds in a variety of qualities such as intensity, duration, and frequency. In my case, there is at times a very intensified alternation of levels, a subtle flow of continuous processing, connecting to the amount of changes of neural activity in the auditory system. There is a discrepancy between what the brain predicts it will hear and the acoustic information that is actually delivered.

Neural signaling is key in both hyperacusis and tinnitus, and so in my work I try to represent the ongoing neural signaling for sound processing. Signalling_01 represents the experience of an “alternate” neurosignaling, illustrating visually the discrepancies between how I expect to hear the world and what I do hear. Signalling_02 represents a continuing auditory signal, a more pronounced and predictable signal that is decoded by the brain. Both of these works represent signals that are sent by the cochlea to the auditory nerve, impulses that transfer information to the auditory center of the brain where groups of neurons work to translate them. My Signalling GIFs are similar to each other, but reveal differences similar to how my hyperacusis might affect my ability to process contrasts in the filtering of auditory inputs, as well as other types of rhythm and patterns.

Bubbling Ups&Downs

Some of the effects of hyperacusis are very distressing, and can build up into phonophobia (fear of sound), misophonia (hatred of certain sound), as well as general related anxiety and depression. In Bubbling Ups&Downs, I interpret some of those moments to reflect the tension of being nowhere, bubbling around with circular emotion, then getting stuck and blocked into a cracked internal linear pain. The response to these moments creates a sense of “limbo,” a sense of being neither here nor there, in movement, slowly. A bit cloudy. A bit stuck. A bit unclear in the direction, ending up with feelings of imbalance and vertigo that relate to the neurological sensory systems in the brain that prepare motor responses in the body. Within the stages of anxiety, there is a sense of “waiting,” of “anticipation” of sounds and pain. A fear that develops with time, often accompanied by a pattern of losing grip on a healthy mood, coming to emotional ups and downs related to the life changes needed, losing control, and entering depression and negative thoughts and energy. These elements are unavoidable when suffering from an acoustic disorder from a trauma that has brought this unexpected and invisible debilitation to everyday life. A cause that is difficult to narrow down and analyze, rationalize; it is made harder through the heavy tiredness it creates, connected to constant neurological work needed to decipher ever-present surrounding sounds. Part of CBT is learning how to cope and respond with some degree of helpfulness. In this piece, I try to group all this together, depicting the feeling of an unclear bubbling of emotional ups and downs, with no distinct direction, risking a crack, but striving to find a way out at some point.

Conclusion

With this collection of artworks, I share some of my first visual considerations and interpretations of hyperacusis and severe tinnitus. This is a chance for me to process and try to mitigate the challenge of living with these conditions, and to visually reflect my feelings in relation to what the acoustic disorders (especially hyperacusis) have brought to me. I want to use media design to explores how arts and design practitioners may also contribute to wider multidisciplinary exchanges, building more inclusive discussions around neuroscience and the arts. And perhaps this work in some small way could be useful as a creative input for audiologists or psychologists, other artists, or patients and people that are themselves going through the different stages and degrees of hyperacusis and tinnitus. This is a small initial window into my personal response, and I will continue to explore this sensory condition more.

There is a dimension of seriality connected to the artworks shared here, with their repetition and reproduction—aspects that connect to the conditions. Despite their differences, there are similarities and affinities within each piece, creating a modularity. The artworks are a response to the acoustic disorder, with fragments of auto-ethnographic observation and symmetrical creative responses. The aesthetics represent the distance and flatness (as I perceive it) of the related neurological condition and physical reactions. This detaches completely from a hyperrealistic depiction of things, as the world becomes more blurred, and glitched, and systematic, and dissected and analyzed. There is also a pattern of keywords found in my observations and reflections, which began inadvertently to occur, that adds to the artworks; it adds to the sense of them appearing “mathematical,” almost algorithmic. In Processing Acoustic Disorder, I connect the issues that I have considered in this essay in an over-layered artwork.

Beyond this point, as an artist and academic, I am continuing to look not only at these conditions but the different disciplines that look at them too—medical, digital, technological, social, and artistic. I hope that my research and artistic work will continue to contribute to this complex, often-hidden, debilitating, painful and yet scientifically fascinating area of my own life, and illustrate how a condition that can be incapacitating can simultaneously be lived with through an explorative lens.

Luca M. Damiani is a Media Artist and a Lecturer on BA (Hons) Graphic and Media Design at London College of Communication. Luca practices internationally in the fields of art, digital media, and visual culture. He works and experiments with creative techniques such as digital technology, illustration-animation, photography, coding, and mixed media. With a multi-methodological approach, Luca explores artistic processes, reconsidering the combination of methods. His ongoing research-based practice looks at various areas of applied art and design, with the main focus on technology, digital art, and neuroscience/neurodiversity. A published artist-author of several books and papers, his work is actively exhibited and showcased. Luca has collaborated with many institutions, including Computer Arts Society, Mozilla Foundation, NESTA, Amnesty International, BBC, Disney, TATE, V&A and Thames & Hudson.

- David Baguley, Don McFerran, and Laurence McKenna, Living with Tinnitus and Hyperacusis (London: Sheldon Press, 2011); Peter U. Diehl and Roland Shaette, “Abnormal Auditory Gain in Hyperacusis: Investigation with a Computational Model,” Frontiers in Neurology 6:157 (2015), at https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2015.00157/full. ↩

- Sharon Goodson and Raymond H. Hull, “Hyperacusis,” American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Audiology Information Series, 2015, at https://www.asha.org/uploadedFiles/AIS-hyperacusis.pdf. ↩

- “Hyperacusis,” British Tinnitus Association, at https://www.tinnitus.org.uk/hyperacusis. ↩

- Larry E. Roberts, Jos J. Eggermont, Donald M. Caspary, Susan E. Shore, Jennifer R. Melcher, and James A. Kaltenbach, “Ringing Ears: The Neuroscience of Tinnitus,” Journal of Neuroscience 30:45 (2010), at http://www.jneurosci.org/content/30/45/14972.long. ↩

- Langguth B., Hajak G., Kleinjung T., Cacace A., Møller A.R., “Tinnitus Severity, depression and the big five personality traits,” Progress in Brain Research, Vol. 166, (2007). ↩

- Luca M. Damiani, “On the spectrum within art and design academic practice,” Spark: UAL Creative Teaching and Learning Journal 3, no. 1 (2018), at https://sparkjournal.arts.ac.uk/index.php/spark/article/view/88/146. ↩

- Mischke-Reeds M., Somatic Psychotherapy Toolbox,(PESI Publisher, 2018). ↩

- Chang H., “Autoethnography as Method, “(Developing Qualitative Inquiry). (Routledge, 2009). ↩

- Salvi R., “Tinnitus and Hyperacusis : Beyond the Ear,” (Audiology Online, 2016). ↩

- Damiani L., “Designing the Mind with Hyperacusis and Tinnitus,” in V&A Digital Design publication “Artificial Intelligent” (V&A, 2018). ↩

- Kirsh D., “A Few Thoughts on Cognitive Overload” (Intellectica, vol. 30, 2000). ↩