From Art Journal 78, no. 4 (Winter 2019)

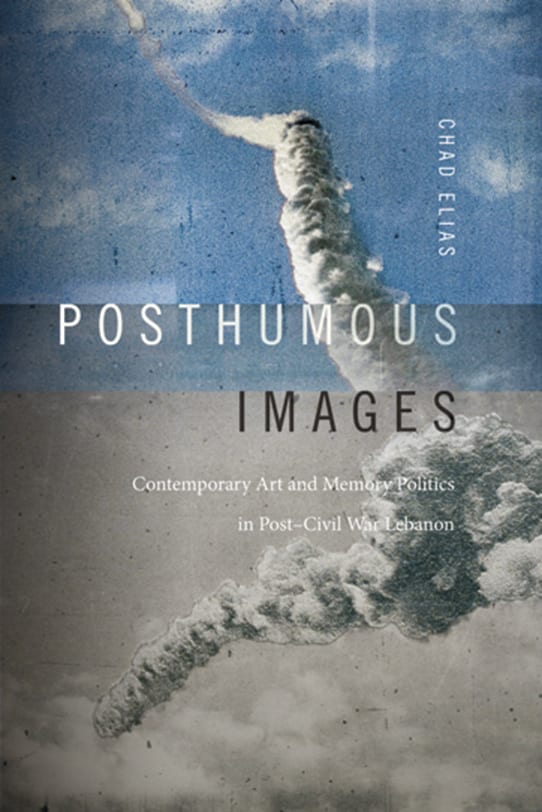

Chad Elias. Posthumous Images: Contemporary Art and Memory Politics in Post–Civil War Lebanon. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2018. 264 pp.; 71 color ills. Paperback $25.95

Clémence Cottard Hachem and Nour Salamé, eds. On Photography in Lebanon: Stories and Essays. Beirut: Kaph Books, 2018. 384 pp.; 380 ills. Cloth $80.00

“If the work is about representation, then what happens to the subjects of it?” (17). So asks Chad Elias in his recent book, Posthumous Images: Contemporary Art and Memory Politics in Post–Civil War Lebanon, a study engaging work by contemporary Lebanese artists Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige (who work as a duo), Ghassan Halwani, Lamia Joreige, Bernard Khoury, Rabih Mroué, Walid Raad, Marwan Rechmaoui, and Akram Zaatari. The book sets out to diagnose, and escape, what Elias dubs the “postmodern bind” of the writing that elevated these artists in the globalizing art world of the 2000s (17). That is, the postmodern tendency to treat “representation” as a register of metacommentary, thereby making Lebanese artists’ conceptual work in photography and video “about” the condition of unstable or lost truth.1 If these tendencies resonated with the deliberate dissimulations surrounding the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, then they also, as Elias’s study reminds, subtended the success of Lebanese artists who returned to Beirut following the 1989 Taif Accords and who made their work from fictional narratives as well as recovered imagery (tactics that Carrie Lambert-Beatty aptly dubbed “parafictional”2). Posthumous Images is the first book-length study of this oeuvre, and it appears some fifteen years after its central artists rose to prominence. Eager to push beyond metahistorical themes, it delivers thoughtful analyses of how reprographic images also retain meaningful connections to their referents.

The question of the survival of referents, and their place in contemporary art’s impulse to remember or commemorate, proves as compelling an inquiry as it is vexed. Happily, a second recent book, On Photography in Lebanon: Stories and Essays, edited by Clémence Cottard Hachem and Nour Salamé, takes up the matter as well. Published by Kaph Books in Beirut, this is a polyfocal anthology of commissioned texts and historical photographs that emerges from current debates about reprographic legacies in Lebanon. The lead editor, Cottard Hachem, serves as codirector of the Arab Image Foundation (AIF), the nonprofit archive of photography from the Middle East, North Africa, and the Arab diaspora first established in 1997 by Fouad Elkoury, Samer Mohdad, and Akram Zaatari. In recent years, the AIF has become mired in internal disagreement over its mission amid a transforming, post-postwar Beirut art world characterized, in part, by investment-oriented foundations in place of do-it-yourself collaboratives.3 Yet its early phase of operations, when it sponsored additional artists—Lara Baladi in Egypt, Yto Barrada in Morocco, and others—to travel, to locate and acquire an astonishing range of photographs, and to produce exhibitions, continues to influence engagement with photographic practice in Beirut. Although the AIF had no direct role in On Photography in Lebanon (instead, we should note, Byblos Bank served as initiator and funder), the impact of its two decades of debates about preservation is discernible. The volume gathers its stories from photojournalists, enthusiasts, scholars, and collectors in addition to artists, and draws on an impressive array of photographic collections. Further, and perhaps most importantly for thinking about photographic material in Lebanon’s contemporary art genealogies, it succeeds in placing the photographic object into an expanded sphere of historical testimony.

In certain respects, the two books may be taken as convergent. They share some of the same references and interlocutors, among them Hadjithomas and Joreige, Khoury, Jalal Toufic, Halwani, and Walid Sadek, not to mention Georges Didi-Huberman and Jacques Rancière. They also feature discussion of several of the same artworks, including Dust in the Wind (2013), a series of images Hadjithomas and Joreige produced as part of their examination of an episode from Lebanon’s Cold War history when scientists created a Lebanese Rocket Society during the 1960s with the intent of developing the first space program in the Middle East. As both books convey to readers, Hadjithomas and Joreige spent several years researching the society’s activities, eventually locating photographs from the successful test launches, only to discover that the photographers all had missed the window to capture an image of the rocket itself. With Dust in the Wind, they give a material form to the rocket’s trailing sediment and its status as a stand-in; molding the shape of the tails in plexiglass, the artists place this layer over the photographs as a dimensional trace of the trace.

But, precisely at the books’ points of convergence, differences of emphasis also appear. Posthumous Images, which uses details from Dust in the Wind on its cover, sees the work as creating conditions for recollecting the past and imagining alternative futures—and doing so despite the collapse of the “nation” as a utopian frame (4, 175). By contrast, On Photography in Lebanon, which has cast its view beyond any particular war or obsolescing dream, offers emphasis on immanence rather than caesura. Hadjithomas and Joreige contribute a first-person essay about the “ontologically photographic” aspect of their practice (205) that links their research on the rocket society (an improbable story that turned out to be true) to new work on conspiracies and scams (untrue stories with real effects in the present).

The phrase “posthumous images,” Elias explains, refers to “the ways in which certain images appear only after the presumed death of their referent” (19). Over the book’s five chapters, he engages—via specific works of “postwar” contemporary art—hostage videos, photographic exhibitions devoted to missing persons, taped testimony by suicide bombers, photos of sites of abduction, and architectural schema, among other posthumous appearances. The contention here, shared by Elias and the artists on whom he focuses, is that the human losses of the Lebanese Civil War cannot be measured in body counts alone. Related contentions have appeared in critical writing by members of Beirut’s experimental arts circles, invoking such in-between figures as the vampire and the sleeper.4 But here, Elias homes in on visual media as harboring latent images, and allowing for animation at later junctures. The formulation proves especially helpful in light of the transformations in the media field that took place from 1995 to 2006, the primary swathe of the book. These include not only the obsolescence of analog photography, but also, in Lebanon, a need to reckon with broadcast media and its effects on communities of witnessing. (As Khalil Joreige once put it, “During the war, every militia had its own media station, television, newspaper or radio . . . audiences or publics had to learn to deal with these images.”)5 Because the battle to capture attention produces authority to narrate the future, Elias is able to pose the further question of whether such “posthumous” images might also harbor, or protect, otherwise unrepresented subjects. For instance, in what state of living are the fighters from occupied South Lebanon who joined Communist militias to fight against Israel, only to be overtaken and rewritten by Hezbollah’s version of the resistance project? How are we to take their presences in these artworks?

Elias devotes his first chapter to Walid Raad, arguably the best known of the book’s artists. This is the only chapter confined to a single artist, and it focuses almost exclusively on a single work, Hostage: The Bachar Tapes_English version (2000), a single-channel video exploring the so-called “Western hostage crisis” by means of video testimony from “Bachar,” an Arab man kidnapped by the same Islamic Jihad militia that held American and British hostages during the 1980s and 1990s. Playing with authorship and authority, Raad initially exhibited the work as the production of Bachar and the Atlas Group, the latter an “imaginary foundation” charged with collecting artifacts relating to Lebanese history (29–30). Elias’s interventions here are double. First, he objects to the supposition that the central figure in Hostage be taken as providing a subaltern narrative to the dominant “Western” one—a characterization that would initially seem supported by Raad’s styling of Bachar as a darker-skinned Arab man and his scripting of Bachar’s testimony around a scene of Western panic at the prospect of homosexual, interracial contact in captivity (45). To Elias, however, at issue in the video is less the matter of excluded identity than the ethics of incomplete translation, manifested by the video’s overdubbing of Bachar’s colloquial Arabic with misleading English translations. Elias draws on theoretical work on translation as a site of resistance to “consensual continuity”—the phrase is Homi Bhabha’s—to take meaning from the noise introduced between Arabic and English when Bachar reports on unwanted sexual contact (29). Second, Elias highlights deliberately poor translations within the video image, including the use of a blue screen, static, and edits to the purloined television coverage meant to disguise provenance. To Elias, Hostage’s performative resistance to translation is its major lesson, for it can be recognized as refusing both the separation of sense from noise and the bridging of gaps opened by translation (51).

Surprisingly, Posthumous Images does not tend to how Hostage also took form as a translation of the artist’s preceding academic work on the “Western hostage crisis,” which Raad undertook at the University of Rochester.6 Raad’s PhD dissertation, filed in 1996, developed a close reading of what he dubs the “captivity memoirs” of the American hostages, mobilizing Eve Sedgwick as well as Edward Said, among others, to track how the narratives marked yet also foreclosed the homoerotics of Orientalism. The study not only informed Hostage but also gave impetus to further metacommentary by Raad in academic journals and exhibition catalogs.7 Elsewhere in Posthumous Images, Elias emphasizes the multidisciplinary and somewhat freeform character of the art scene in post–Civil War Beirut, where artists played many roles and could proceed as “interested in histories without being a historian” (19, quoting from Zaatari). Yet, as attested by Raad’s writing in academic venues, these practices were not isolated to Lebanon. As was known to audiences in Beirut, many of the “new media” artists who exhibited as a cohort working in video, film, and installation were actively building careers between places as well as between fields, collaborating with artists and activists in the diaspora, and publishing widely. For instance, a special folio prepared by Jalal Toufic for the cultural journal Al-Adab—published January 2001 and featuring essays by himself, Hadjithomas and Joreige, Mroué and Tony Chakar, Raad, Sadek, Ghassan Salhab, and Zaatari—acknowledged the linguistic spread of the writing and made a case for translating texts by Lebanese artists writing in English (Toufic and Raad) or French (Hadjithomas and Joreige) into Arabic.8 Because Posthumous Images suggests, convincingly, that research activity in artistic practice should be recognized as genuine historical work, the book’s muteness about other pertinent circuits of translation between institutions and languages is a missed opportunity.

Chapter 2, titled “Resistance, Video Martyrdom, and the Afterlife of the Lebanese Left,” focuses on two artists, Mroué and Zaatari, each of whom employ strategies of reenactment in works meant to highlight the plight of fighters, associated with left-wing resistance to Israel in South Lebanon during the 1980s, who engaged in resistance from a “border zone” that existed in near complete segregation from the rest of the country. The chapter’s discussion unfolds around a central periodization: the rise of Hezbollah, with its religious idioms of valor and heroism, following the 1982 Israeli invasion and capture of West Beirut, events that included the forced ouster of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and spelled defeat for secular resistance forces (63–64). Both of Elias’s primary artistic cases arise, in part, from parallel developments in television. Zaatari made the documentary video All Is Well on the Border (1997) when he was working at Future TV, a satellite station established in 1993 by Prime Minister Rafik al-Hariri that had begun to air the largely formulaic testimonies of former detainees upon their release from Israeli prison and return to Lebanon. Dedicated to the deferred history of the border zone, his video features scenes of actors who respeak these lines, heightening the estrangement. Mroué’s Three Posters (1999), a multimedia performance he wrote with Elias Khoury and performed alone, also plays to the problem of ideological glitching. Its “reenactment” takes as a script a taped testimony the artist discovered in the archives of the Lebanese Communist Party. In contrast to the conventional martyr testimonies that television stations regularly aired in the mid-1980s, the rediscovered tape featured three “takes” of the testimony with only slight, yet moving, differences. The opening claim of this second chapter is that war was fought “with and over images” as much as by the constituencies these images are made to stand in for (55). By way of demonstrating the point, Elias tracks the use of “live-action mortality” for political ends, including into Hezbollah’s own videos and posters using the bodies of martyrs to “speak” its messages (94).

Elias turns to the status of more than eighteen thousand missing persons in Lebanon in the next chapter, devoting his closest attention to four projects by artists who challenge state-imposed amnesia on the subject: small and poignant street drawings by Halwani, whose father is among the missing and whose mother has led campaigns for representative justice; the photographic works titled Lasting Images (2003) and the film A Perfect Day (2005) by Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige; and a documentary, titled Here and Perhaps Elsewhere (2003), by Lamia Joreige. All are contrasted with concurrent memory-oriented initiatives sponsored in the NGO sphere, such as an exhibition of donated photographs of the missing organized in 2008 by a group called UMAM. In the framework of Elias’s analysis, Lamia Joreige’s Here and Perhaps Elsewhere makes for the most intriguing departure from standard memory politics, for she filmed her interactions with inhabitants of Beirut neighborhoods as she shows photographs of former checkpoints and asks, “Do you know anyone who was kidnapped from here during the war?” Elias discusses how, as a result of the question structure, anyone who volunteers information is also claiming the personalized authority of somehow knowing this missing person. The documentary thus serves to register how different kinds of knowledge of people and wartime acts are gendered and spatialized in the city.

The fourth chapter of Posthumous Images detours away from the media most commonly thought to produce representational documents and toward architecture. Supposing that urban forms might also act as witnesses to the traumas of the past, Elias brings in versions of urbanist work by Bernard Khoury and Rechmaoui. Of the several pieces by Khoury discussed, Evolving Scars (1991) is an earliest experiment in “postwar architecture,” and it developed outside Lebanon at the Harvard design school. In 1991, the downtown area of Beirut was “still a no-man’s-land” and had been given no clear plans for reconstruction, yet architects and others invested in urban history already opposed the Hariri government’s creation of the private Solidere entity to raze and rebuild, recognizing the replacement of the physical scars of war by profit-driven centers as a threat to public interest (150). Khoury’s Evolving Scars may be understood as a proleptic response: he proposed to fit damaged buildings with transparent skins, which would then serve as “memory collectors” of their future demolished debris. Elias opts not to detail particulars of the artist campaigns that opposed Solidere’s demolitions in favor of exploring how artistic practice over a longer durée might highlight continuities of inhabitation and spatial adjustments, rendering built form into another posthumous testimony. Rechmaoui, for instance, makes models of modern apartment blocks that reveal patterns of 1970s retrofitting that accommodated refugees from the impoverished countryside. The same emphasis on the revivals of reuse allows Elias to characterize Khoury’s later, highly controversial B018 nightclub project in the Karantina neighborhood, built on a site of a 1976 massacre of Palestinian refugees by Christian militias, as a critical gesture “unsettling] the idea of the monument as a space of mnemonic reflection” (156).

Finally, chapter 5 focuses on the artistic outcomes of Hadjithomas and Joreige’s research on the Lebanese Rocket Society (discussed above). Elias presents a gripping reading of The Lebanese Rocket Society (2013), a ninety-five-minute documentary film, and its exploration of the fissures in shared and sharable imaginaries that had come to make a “Lebanese Rocket Society” seem unthinkable. Of all the artists considered in Posthumous Images, Hadjithomas and Joreige have most consistently stated that they took up questions of representation and of what war does to images, because the available iconographic conventions for depicting ruins are inadequate to the rupture. So it is meaningful that the interest in The Lebanese Rocket Society lies with a heritage of utopian imaginaries and pan-Arab aspirations in which the artists struggled to see themselves. As Elias puts it, the film “asks what meaning these images can have when the thread of history connecting them to the present has been broken” (163). In compelling and even beautiful prose, Elias follows the film through its final turn to science fiction and to a concluding animation sequence, made by Ghassan Halwani, showing street scenes of Beirut amid a Lebanon that “has secure borders and oil money” (i.e., the national spoils procured by continual advancement in rocket and satellite technology). As in all the chapters of Posthumous Images, Elias raises questions of asynchronous chronology and its interpretive stakes. We are asked to recognize how the artists have retained the bullet holes of the landmark Martyrs’ Monument in the animated sequence, despite its overall counterfactual premise. As such, even this imagination of technological emancipation would seem to hold the possibility that the war still did happen, and that alternative futures would not be free of its traces.

This is a stimulating study, impressive in its writing. Because Elias builds his chapters upon a culled selection of work, there is space for him to construct his claims through elegant constellations of references to theorists rather than direct citations of historical studies. The result is a book that gives air to both its readings and possible gaps in those readings’ explanatory power. Elias makes occasional reference to a generic viewer in Lebanon, as well as to “audiences outside Lebanon,” but his is not a social history attentive to stratified response. Rather, it is a correction to the art world commentary that miscast these works as being “about” a postwar condition. Elias is entirely convincing on this point, and Posthumous Images shows us how the works are also about, for instance, the subjects of struggle in South Lebanon and the political content of their deaths as well as their lives.

Less certain is the extent to which the author has sought to depart from the artists’ characterization of their interest in representational regimes. These are artists who wrote prolifically and honed theoretical positions with sophisticated audiences at festivals and conferences. Indeed, at initial screenings of the video Hostage, Raad typically delivered a lecture-performance as a component of the piece. Sarah Rogers’s important 2002 article on the Atlas Group—oddly dismissed in the book as putting forward “now-standard” claims about the destabilization of fact and fiction (33)—developed a reading of hysterical symptoms in the work in part by analyzing Raad’s own cues at performances in Beirut in 1999 and at the Whitney Biennial in 2002.9 Given the inextricable relationship between artists’ metacommentary and the reception of these works, Posthumous Images wants for an honest discussion of the challenges involved in either using these commentaries or breaking from them. What new evidence is needed in order to read these works in the negotiated memory politics to be found on the putative ground?

Precisely where Posthumous Images is selective in its arguments, On Photography in Lebanon: Stories and Essays puts forth an expansive view of visual practice in Lebanon. Its materials date from 1842 until 2017, and its pages contain forty commissioned texts. As such, the editors makes their case for continuous activity by offering the reader a profusion of intriguing documents and recollected stories. Clémence Cottard Hachem begins her introduction by recounting several anecdotes of historical grappling with the photographic process of converting light into image: the eleventh-century thinker Hasan Ibn al-Haytham’s modeling of the eye as an optical instrument, the use of chemical developments to “fix” images by inventors in nineteenth-century Europe, and the Kodak company’s suppression of its digital camera, which it patented in 1978, out of fear of losing film sales. More is at stake here than simply evincing wonder at technological change. The book also acts as a primer in photographic analysis for those more accustomed to digital conditions, providing a glossary of photographic terms (“photosensitive surface,” “chromogenic color negative,” “contact printing,” and so on) and placing individual appearances of these terms into boldface type throughout. The introduction concludes by identifying six vectors of consideration meant to double as suggested pathways for navigating the subsequent materials. These are the “operator,” defined by the gaze of the photographer; the “apparatus,” meaning the mechanics of photographic practice; the “referent,” defined as the subject of representation; the “object,” defined as the body of the image; “transmission,” defined, somewhat idiosyncratically, as the life of the image; and the “viewer,” defined by poetic parataxis as “the image as memory, the image as narrative.” These selections convey a wariness about strictly structuralist approaches that make images “signify” in the absence of specific viewers.

Thanks to the volume’s exquisite reproductions, this reader found the keywords fairly unnecessary as prompts. Whether a page from a 1904 photo album showing Beirut city views, labeled “Voyage en Syrie,” or a 1980 photo of a runaway horse in a deserted Beirut Airport by Georges Semerjian, the images on their own offer enticement to ponder the interplay of object, referent, and so on. Indeed, in a later note about nineteenth-century photographs in the collection of Philippe Jabre, Cottard Hachem mentions that she and Nour Salamé conceived of the true-to-scale reproductions as providing a “phenomenological dimension[,] enabling everyone to observe and experience what these images do” (302). On Photography in Lebanon excels at staging meetings between texts and images so as to open a sense of discovery. For instance, the first text of the book (if read from beginning to end) is a conversation with nonagenarian poet and artist Etel Adnan, touching on intersections of photography and intellectual formation in her life. Adnan describes, movingly, her childhood encounter with stunning black-and-white photographs of the Lebanese mountains by the Armenian photographer Manoug Alemian. And yet, whereas Adnan supposes that the prints have been lost, going so far as to invoke a cultural propensity to nonattachment in Lebanon, On Photography in Lebanon enacts a plot twist by recovering and featuring several Manoug landscapes on its subsequent pages. They are digital inversions of negative images that were rescued from cellulose acetate sheet film discovered among the artist’s papers at the American University of Beirut. Here revived on the paper page, their full spectrum of rich, middle tones appears as present as ever.

None of the essays in On Photography in Lebanon are long, and they cover a great deal of ground in terms of type of narration and personal positioning. One finds evocative texts probing the technical properties of early photographs, such as notes on dimensionality in color photographs (by Yasmina Jraissati) and on turn-of-the-century scripts for experiencing landscape (by Adrien Zakar). Contemporary art historians already familiar with the broad outlines of Lebanon’s postwar art world will find contributions from Dominique Eddé, Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, and Gregory Buchakjian especially valuable for their read on the institutional conditions for efforts to, as Eddé puts it, salvage memories for the future (85). Eddé describes why and how she commissioned the photography book Beirut City Centre (1991), a volume with Solidere sponsorship that later became an object study for critics who opposed efforts to neaten war-torn Beirut.10 Wilson-Goldie details the phases of the AIF’s aspirations with her trademark incisiveness, and Buchakjian’s essay, titled “Photographic Ruins, Photography in Ruins,” discusses developments that followed the publication of Beirut City Centre, which in part yielded the Atlas Group. One also finds calls to arms for the cause of heritage preservation, as in newspaper columnist Mohsen Yammine’s recollection of collecting glass plates from his home region of Zgharta, in the North, in the 1970s. Most gripping of all are the commentaries collected from photojournalists who covered the civil war and who share details of their craft (thanks to astute interviews by Cottard Hachem), including the locations of film processing facilities, the instructions of photo editors, and, in the case of Aline Manoukian—the first Lebanese woman photojournalist to cover the war (1983–90)—the use of a Red Cross ambulance to catch a scoop. Manoukian is asked to name some of the images that most affected her, and her testimony, in turn, prompts the reproduction of a still-shocking news photograph of young Christians who play the oud in celebration of the death of a Palestinian girl (277).

Finally, whereas the most recent projects discussed in Posthumous Images date to 2013 and 2014 and are mobilized as updates to the earlier core concerns, On Photography in Lebanon pushes to the present day and contemporary concern for not just “images” but also their digital-biological mediation. A collaborative work by Randa Mirza and Lara Tabet, published under the pseudonyms “Jeanne et Moreau,” tracks a love affair between two women photographers via simulated chats and casual nude snapshots that invite desire despite (or because of) their existence in a digital archive (269). A second kind of inquiry into the matrix of pixels and flesh drives the work that appears on the cover of On Photography in Lebanon: Vartan Avakian’s Suspended Silver: Dispersion 50 (2015), which the artist created from his excavations of a photographic studio in a derelict building. Having gathered its decades’ worth of debris, Avakian sifted out a number of silver particles that flaked off old rolls of film and scanned, enlarged, and printed them on black backgrounds, where they come to resemble cosmic clusters. In his essay, “Your Skin Shall Bear Witness Against You,” Avakian explains that the dust of the studio harbored not only silver flakes of photographic image-data about people (“material equivalent of pixels”) but also human epidermis shed by former customers (52). Avakian, who belongs to the cohort after the so-called “war generation” but whose Armenian lineage makes him a subject of still longer histories of dispossession and death, constructs this work as an appeal to the organic alongside the digital—with all the ambivalence about identification that this entails. Far from coldly conceptual, these fabulist tales of scientific recuperation perform a kind of personalized and personalizing work, for now it is DNA evidence that serves to confirm the dead and, indeed, to track family constellations of descendants and property claims.

Two books offer approaches to expanded photographic practice in Lebanon, each by recourse to crucial supplements. On Photography in Lebanon makes sure to correlate object to memory, not just of “what happened” but also of how a shot was shot, so that the subject of representation may be said to be the photographer, or the collector, or even the scavenger and consumer. Devoid of either index or straightforward table of contents, it sheds the pretense of dispassionate archival display that might otherwise be the expected aesthetic. And, because it allots space to both pleasure and horror, it does not build to any particular view on either the politics of representation or of being represented, nor on the use of a nation-state—that is, “Lebanon”—as an organizing frame within which antagonistic relationships of class, sexualized identity, or sectarian ties become visible nevertheless (a notable exception being Stephen Sheehi’s “Can the History of Lebanese Photography Be Written?”). It is Elias who directs his book, Posthumous Images, to the question of what becomes of subjects of representation. He insists on a second point of reference, that of the images recorded in a moment of proximity to living persons that then outlive—and yet also reanimate—their subjects as reprised in contemporary art. There is an elegiac quality to Posthumous Images, sustained, at times, by a habit of relegating political conflict to a past moment without quite detailing the tension or the wider representational concerns of the artists in question, which in fact included links to political action beyond Lebanon “proper.”11 These are the frustrations of a slim study. Ultimately, Posthumous Images places the question of possible yet incomplete representation back into play, showing it to be of vital concern for critical writing about modes of capture and replay now and in the future.

Anneka Lenssen is an assistant professor of global modern art history at University of California, Berkeley. She writes on modern painting and contemporary visual practices, with a focus on the cultural politics of the Middle East. Lenssen is coeditor of Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents (MoMA, 2018), an anthology of translated art writing from the Arab world, and her monograph, Beautiful Agitation: Modern Painting and Politics in Syria, is forthcoming from the University of California Press (2020).

- For discussions of developments such as the “archival turn” and its intersection with contemporary practice by these artists, see Dissonant Archives: Contemporary Visual Culture and Contested Narratives in the Middle East, ed. Anthony Downey (London: I. B. Tauris, 2015). Elias contributes an essay, “Walid Raad’s Projective Futures,” to the collection. ↩

- Carrie Lambert-Beatty, “Make-Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility,” October 129 (Summer 2009): 51–84. The same issue of October included Vered Maimon’s article, “The Third Citizen: On Models of Criticality in Contemporary Artistic Practices,” which discusses the work of Walid Raad and makes clearest the Iraq war context. ↩

- See the discussion by Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, “Memory Games: The Arab Image Foundation,” in On Photography in Lebanon, 146–51. In May 2019, the AIF announced a relaunch of its online platform with 22,000 digitized images out of its some 600,000 items. ↩

- See Jalal Toufic, (Vampires): An Uneasy Essay on the Undead in Film, 2nd ed. (Sausalito, CA: Post-Apollo Press, 2003); and Walid Sadek and Bilal Khbeiz, al-Kasal (Indolence), a newspaper collaboration reprinted in Tamáss: Contemporary Arab Representations, vol. 1, Beirut/Lebanon, ed. Catherine David (Barcelona: Fundació Antoni Tàpies, 2002). Al-Kasal, first printed in the cultural supplement of a daily paper in 1999, showed large photographic images of “sleepers,” men lying incapacitated on the floor, neither dead nor awake. ↩

- Chantal Pontbriand, “Artists at Work: Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige,” Afterall Online, September 12. 2013. ↩

- Walid Raad, “Beirut . . . (à la folie): A Cultural Analysis of the Abduction of Westerners in Lebanon in the 1980s” (PhD diss., University of Rochester, 1996). ↩

- Walid Raad, “Bayrut Ya Beyrouth: Maroun Baghdadi’s Hors La Vie and Franco-Lebanese History,” Third Text 10, no. 36 (1996): 65–82; and Walid Raad, “Civilizationally, We Do Not Dig Holes to Bury Ourselves (Excerpts from an Interview with Souheil Bachar),” in David, Tamáss, 124–37. ↩

- Jalal Toufic, “Muqaddimat al-milaff: ‘Adam al-fahm bi-dhakā’ wa-rahafa,” Al-Adab 49, no. 1/2 (January–February 2001): 8–9. The special issue indicates that even this introduction has been translated by the journal’s editors. ↩

- Sarah Rogers, “Forging History: Performing Memory: Walid Raad’s ʻThe Atlas Project,’” Parachute 108 (2002): 68–79. ↩

- See miriam cooke, “Beirut Reborn: The Political Aesthetics of Auto-Destruction,” Yale Journal of Criticism 15 no.2 (Fall 2002): 393–424. Discussion of Solidere follows Saree Makdisi, “Laying Claim to Beirut: Urban Narrative and Spatial Identity in the Age of Solidere,” Critical Inquiry 23. no. 3 (Spring 1997). ↩

- See, for instance, Mroué’s 1998 collaboration with Chakar, Come in Sir, We Will Wait for You Outside, which aimed to rethink representations of the Palestinian Nakba. Its Arabic-language script is included in the 2001 Al-Adab folio mentioned in note 8. ↩