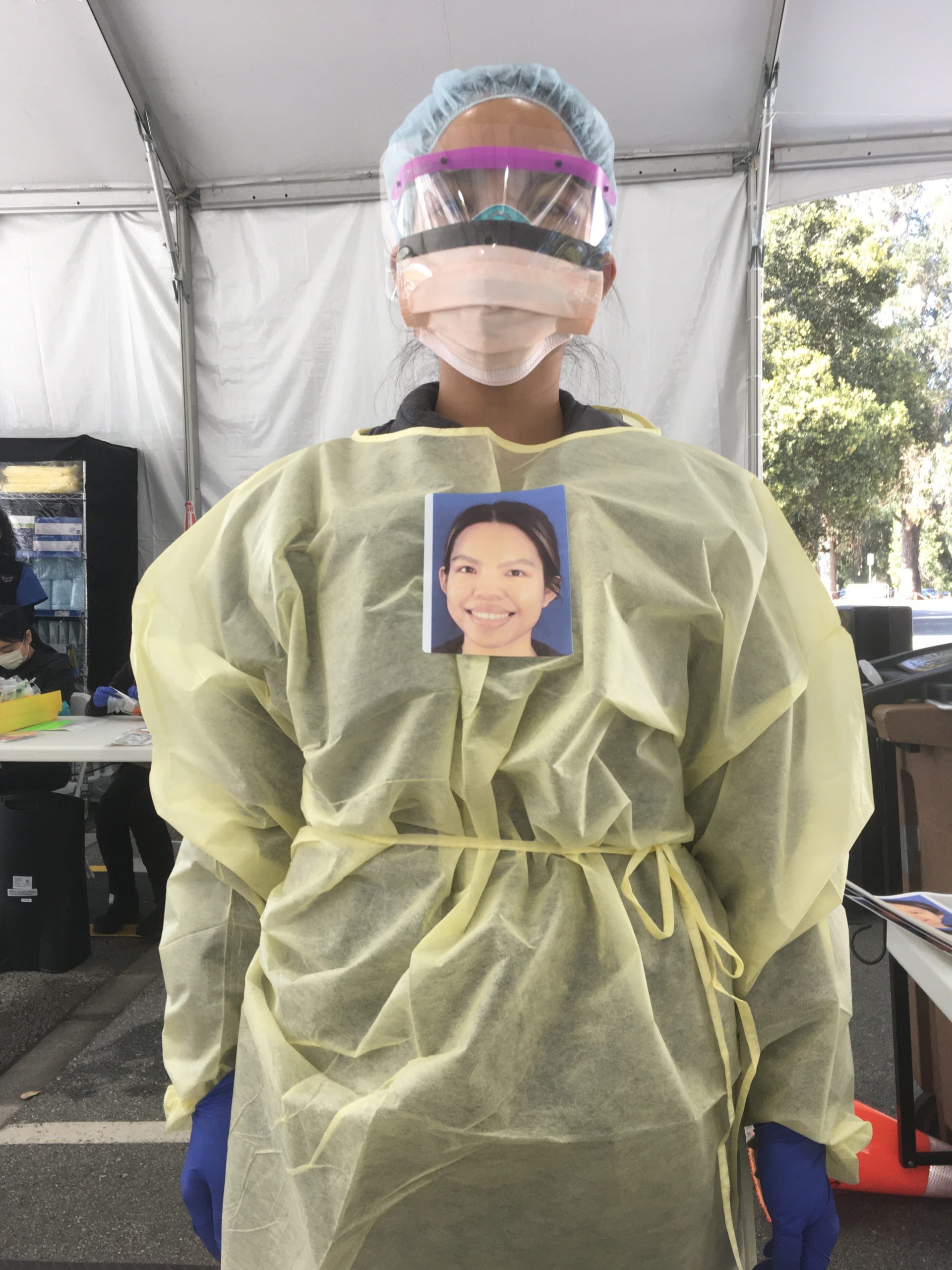

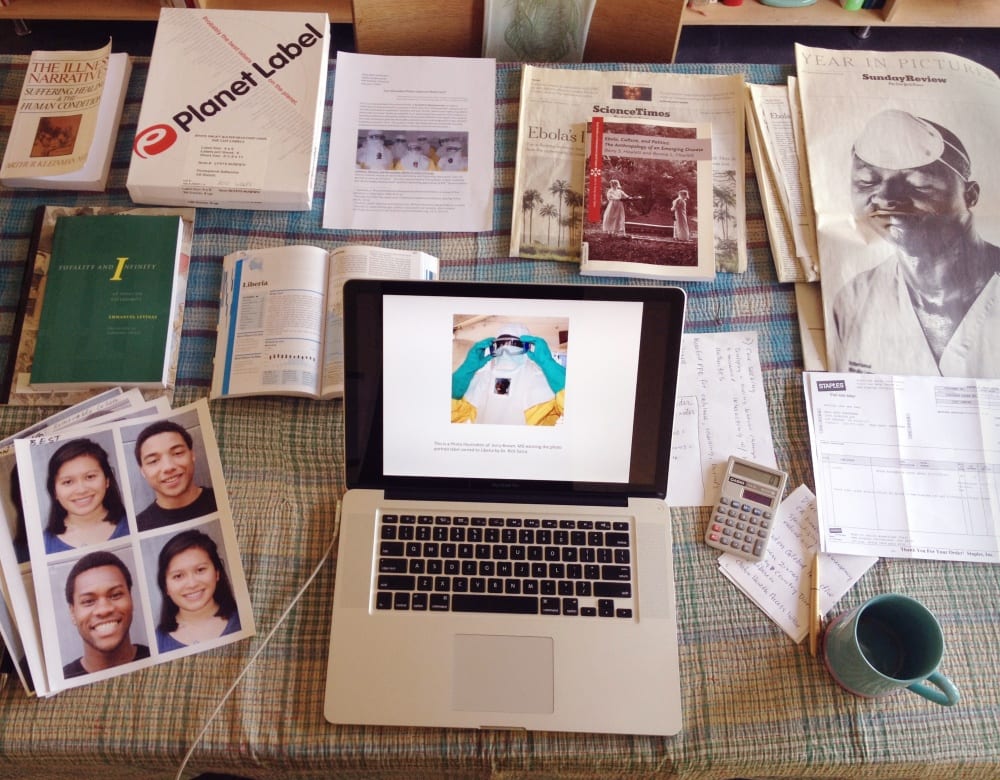

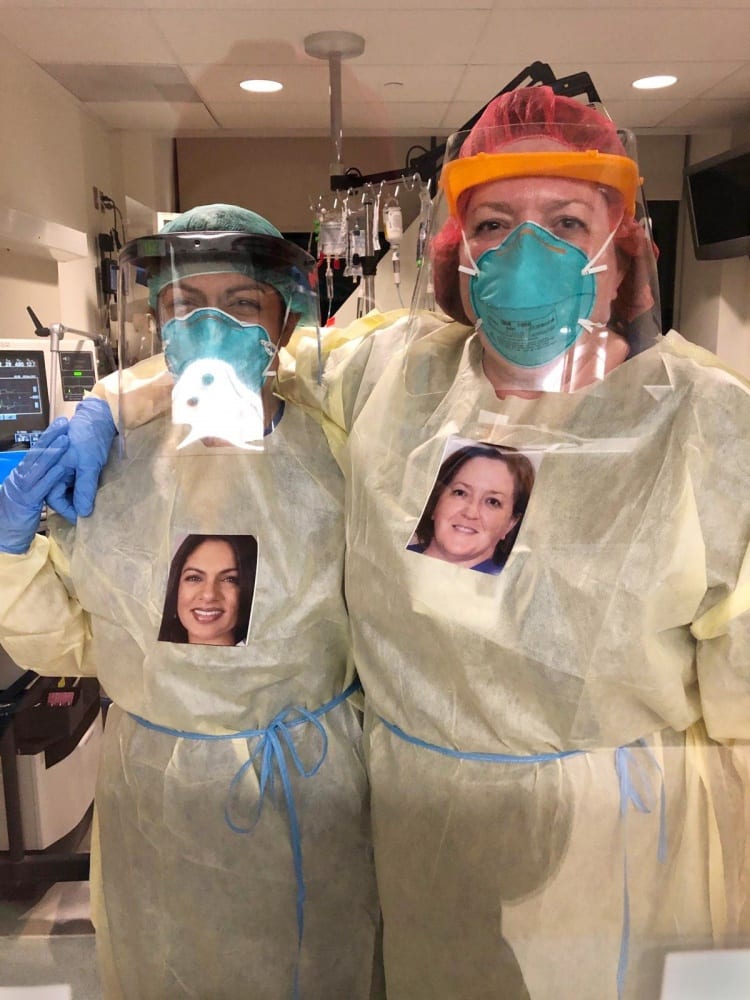

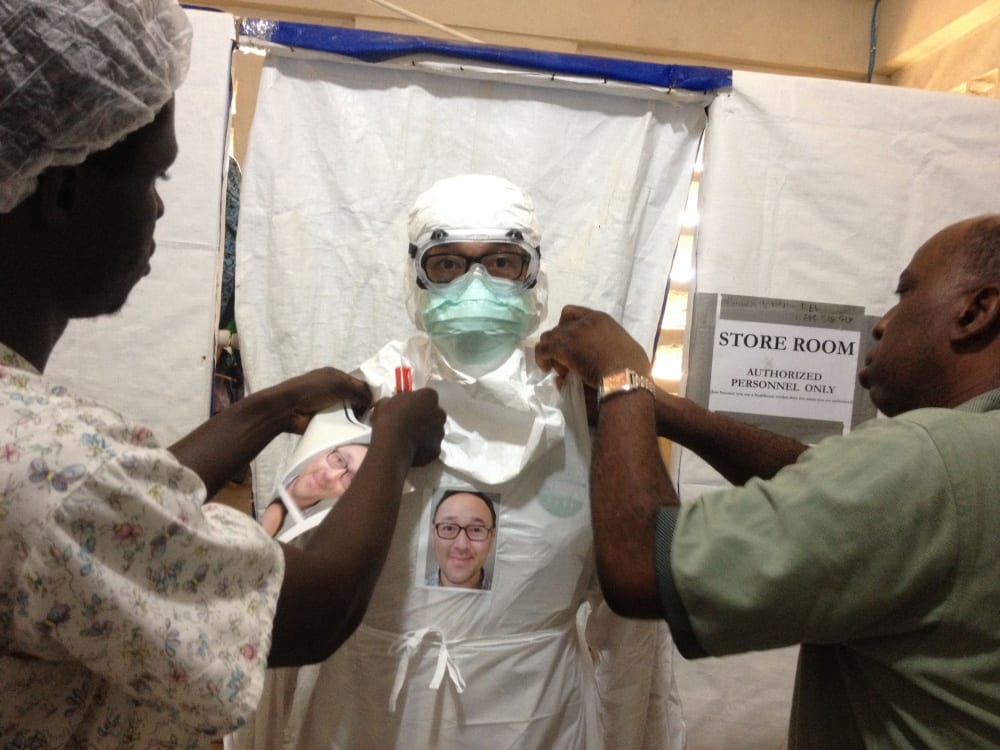

In the midst of the Ebola crisis in 2014, Los Angeles–based artist and professor Mary Beth Heffernan unveiled her PPE Portrait Project, using photography to reveal the faces of mask-wearing health-care workers as a way to build trust with patients and to mitigate the impersonality of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as hazmat suits. Working closely with an extensive network of doctors, biologists, public health experts, and a few governmental ambassadors, Heffernan ultimately partnered with the Liberian Ministry of Health to take portraits of caregivers and affix them to hospital uniforms, navigating an extraordinary number of tricky logistical complications, both bureaucratic and virological.

Now, in the midst of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Heffernan is teaming up with an array of US institutions that have recognized the psychological and physical benefits of her initiative for both patients and providers. Though the PPE Portrait Project has been widely written about, as well as featured on CNN and The Rachel Maddow Show, I wanted to take a deeper look into some of the underlying political stakes of her initiative, and she graciously agreed. We conducted this interview remotely in mid-May as we both sheltered in place.

—Julia Bryan-Wilson

Julia Bryan-Wilson: Throughout your wider body of work, you confront issues of representation, corporeality, and vulnerability, often with a focus on bodies, skin, and flesh. The first photographs I saw of yours, in 2006, were taken near the Marine Corps base in Twentynine Palms, California, and depicted freshly inked tattoos, with a focus on memorial tattoos for fellow Marines who died in the Iraq war (The Soldier’s Skin). These are intimate close-ups that were clearly made possible by a lot of respectful dialogue with the Marines themselves. Let’s talk about the genesis of your PPE project, which was a response to a very different kind of photography about death—the reportage around the Ebola crisis, which felt more focused on the rapacious consumption of Black morbidity for privileged white audiences than it did on respect.

Mary Beth Heffernan: Much of the reportage at the height of the Ebola epidemic generated fascination, horror, and disgust—for suffering Black bodies, for the most extreme effects of an “African” disease, for certain neighborhoods and living conditions. The reportage disparaged West Africans as appearing to value neither scientific expertise nor the interventions of international aid agencies. Not surprisingly, the words and especially images hewed closely to colonialist representations of African otherness.

“Horror” and “disgust” are the very terms that Susan Sontag takes on in Regarding the Pain of Others, underscoring often problematic identification with others’ suffering. In the West African Ebola epidemic, did news photographs and captions simply shore up neocolonial attitudes toward Africa? Did they provide a vehicle for human fascination with another’s pain? A means to empathize with the Liberian people? I think all three are true. There is a particular image and caption that comes to mind: New York Times freelance photographer Daniel Berehulak’s photograph captioned “Eric Gweah, 25, weeps as a burial team removes the body of his 62-year-old father, who died at home, arms thrashing and blood spewing from his mouth, in front of his sons after being turned away at the treatment centers in Monrovia, Liberia. ‘The only thing the government can do is come for bodies—they are killing us,’ Gweah said” (September 18, 2014). The photograph and caption perform this trifecta in depicting the face of the young Mr. Gweah, a rictus of pain—comparable to that of the image of Phan Thanh Tam in the foreground of Nick Ut’s iconic 1972 photograph The Terror of War.

Circling back to the origins of Soldier’s Skin and the PPE Portrait Project, if the former took a lot of respectful dialogue, especially listening, the latter involved close readings of Ebola survivors’ stories, in particular the first-person narratives of doctors who became infected and lived to write about it. Their stories were electrifying, and the words they chose to describe their experience—of being sick, isolated, and the trauma of not seeing a human face in their caregivers—are seared in my mind.

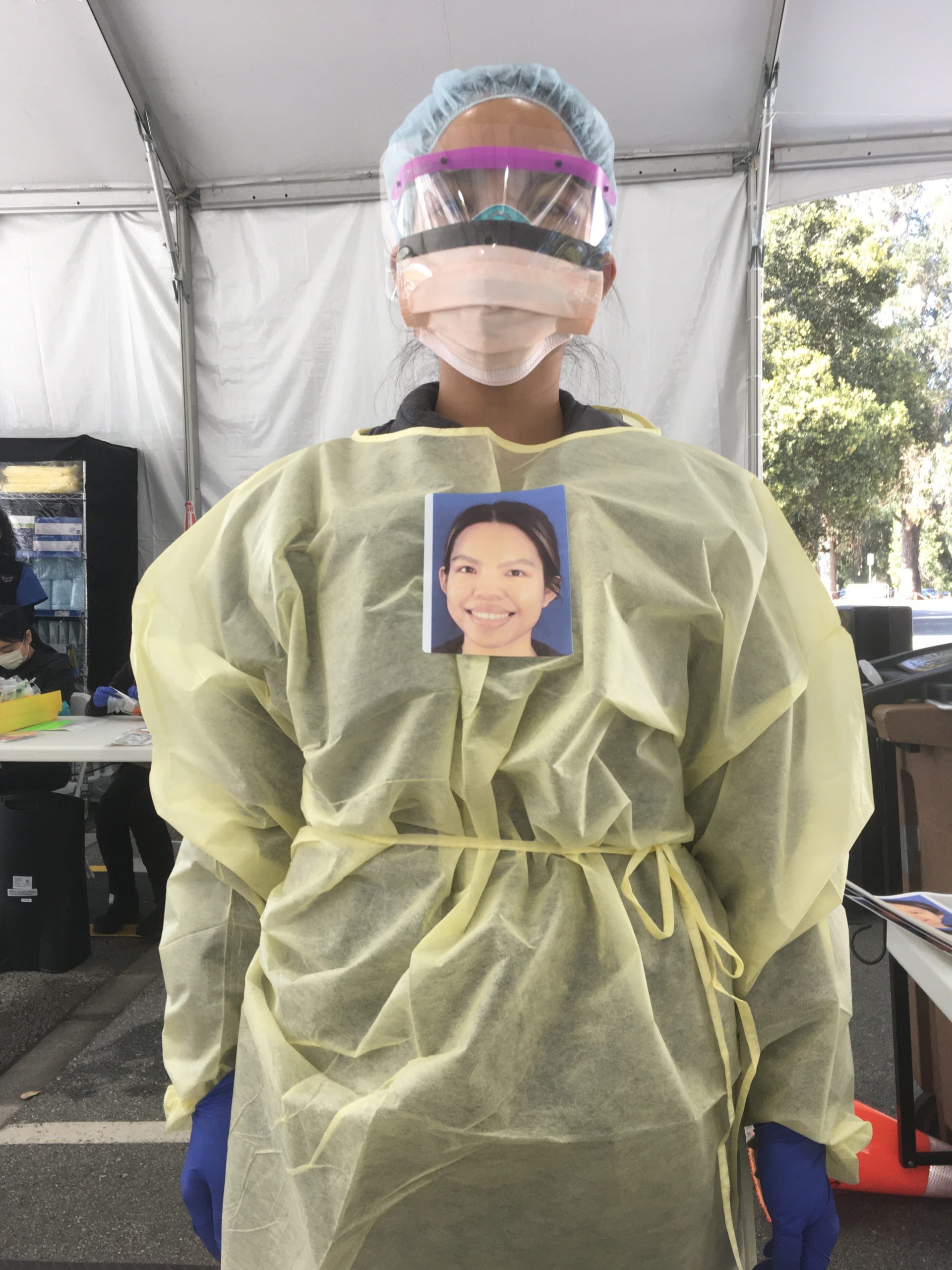

Bryan-Wilson: The PPE project required an enormous amount of scientific and medical research, including materials tests for photographic paper and on-site printing and for the complexities of donning and doffing safety protocols. Much artistic making is made possible by rigorous research, though that is often ignored in favor of myths about creativity and inspiration. Can you describe some of your process to me and talk about how you conceive of art as a form of research?

Heffernan: I see art making as a way of suturing together seemingly disparate things in a way that makes new sense, or of making something rigorously and delightedly “wrong”—that is, to use Gayatri Spivak’s wonderful term, scrupulously fake. Art making is a way of knowing the world, and that’s why, for me, research is an intrinsic part of that process.

In the PPE Portrait Project, research was also a form of respect—for the patients and health-care workers whom I was seeking to support; for the communities, the health professionals, and countries whose collaboration I was seeking. And respect for all the formidable dimensions of the disease itself. You don’t go wading into an epidemic without doing your homework.

In addition to the medical literature on the psychological effects of source isolation and the physiological effects of positive social gestures, I also sought out information about the local uses of photographs, particularly around illness or death. For example, I did not want to propose a project to place headshots on health-care workers’ chests if there was, say, a funereal tradition of placing photographs on coffins. Research is a form of humility and accountability, a way to practice cultural competence.

Research is like learning a new technique—it expands and deepens the possibilities of response.

Bryan-Wilson: This project is emphatically collaborative, and depending upon the audience, your authorship is quite variably highlighted. Sometimes you are prominently listed as “the artist,” but sometimes the hospital takes ownership and your name is not as visible. How do you think about the art-market demands of single authorship versus sharing credit?

Heffernan: Might we tease apart the art market and art world(s)? The art market simply ignores projects like these because there’s nothing to see and nothing to sell. Even art worlds that value “social practice” tend to focus on dynamic or messianic personalities. Art institutions, grants, awards, and residencies reward individual artists and, more grudgingly, collectives—and even more rarely, art collaborations involving ordinary people. The success of the PPE Portrait Project is predicated on “the artist” receding from view and ultimately disappearing as the project is picked up and practiced by others outside the art world. The “art” is not the adhesive portrait: the portrait is simply the spark for the human connection between the patient and caregiver. The PPE Portrait Project is more catalyst than object. Until recently, it hasn’t been legible in the medical world or the art world.

Bryan-Wilson: Your emphasis on portraiture focuses on the importance of the face as a conveyer of empathy and compassion. Your photographs offer faces that would otherwise be occluded by masks, shields, and goggles, and give the patient something to latch on to so they aren’t forced to, as you told me, memorize their doctor’s shoes. This brings me to the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas and his proposition that ethics is a responsibility to an “Other,” who must be met with a face-to-face encounter. The primacy of the face, and its ability to communicate specificity and humanity, has long been utilized by activists as well as artists; I’m thinking about the use of identification photos of the “disappeared” in protests against military dictatorships in places like Argentina and Chile. And more recently, I witness the dignifying attention given to the visages of Black people murdered by police, such as George Floyd, whose face has become a rallying cry for Black Lives Matter. I have seen many protest posters that simply feature his face; that statement needs no words. Do you have a theory of the face? Or a response to the Levinasian idea of ethics as grounded in the face?

Heffernan: These are vital, urgent examples of the use of faces to particularize and humanize loss. The protest portraits of George Floyd not only proclaim, “I Am a Man!,” but they are specific, visual embodiments of his personhood. When we see an image of his face, we see the face that his children kissed, the face that his mother beheld, the face that was touched and loved. When we view the portrait of his face, we are thrust in the ethical position of an interpersonal relationship. This is the dynamic I hope to harness in the PPE Portrait Project. The project is deeply informed by Levinas’s ideas about a responsibility to an other via the face-to-face encounter, and also by its impossibility in the material conditions of an epidemic. Here, the portrait is a proxy for that presence, even as it flags the absence of the face-to-face encounter.

If I have a theory of the face, or a portrait standing in for a face, it is entirely bracketed by what I once described as this “theater for two.” The portrait you wear for a vulnerable patient is always and only your own image, preferably made expressly for this purpose, offering the expression you wish the patient could see. It is a unique currency; it does not instantiate varying degrees of worth or a hierarchy, like ID badges. PPE Portraits, like faces, are of equal worth, of an equal but immeasurable value that one exchanges with an other to affirm their mutual humanity.

Outside of that dyad, and the insular community of anonymous masked health-care workers, the meaning of a face, and photographs of faces, atomizes. The deeply problematic history and present-day instantiations of physiognomy, anthropometry, surgical and digital manipulation, facial-recognition technologies, surveillance, spectacle, celebrity, and social-media culture makes the face as mercurial as it is necessary and enduring.

Bryan-Wilson: What is a face? Is it still a face when augmented or veiled? I wonder, for instance, how a Muslim woman in a burka might respond to the assumption that the face is the only thing that humanizes us . . .

Heffernan: I wouldn’t attempt to speak for Muslim women who wear burkas. I don’t believe the face is the only thing that humanizes us; that would be our behavior, how we treat others. I would argue that one elects to veil the face because of its power and status as a face, and that it’s also a powerful thing to withhold the face from public view.

When I was a younger woman, walking in the city lost in thought, men of all ages would routinely call out, “You’d be prettier if you smiled!” This made me seethe. So when I ask health-care workers to smile for a PPE Portrait, I am particularly mindful of what it means to ask someone, especially a woman, to smile for the benefit of others. Research shows that a smile perceived to be authentic engenders trust and cooperation, and this warmth can activate the patient’s own healing mechanisms. This is what I try to foster in the PPE Portrait Project. And this is also why the project is voluntary, and its use solely within the context of the patient/health-care worker encounter.

What is a face? How, why, and when does it operate? Consider the case of babies, who need the consistent face of another to become their own healthy and independent beings. My understanding of a face is informed by many disciplines, from Levinas and French phenomenology to attachment theories and the latest neuroscience: all underscore the centrality of the face in generating empathy, compassion, and ethical behavior toward others. For those of us who are sighted, it is the densest, most sensorially rich, dynamic, mutable, and expressive site on our bodies, the emblem of our unique selves, and often what enables those around us to feel human, too.

Bryan-Wilson: The PPE Portrait Project has been described as social practice, but we might also think of it as “useful art,” to use Tania Bruguera’s formulation. It is also in conversation with the Black women’s care projects of Simone Leigh and the policy advocacy of Laurie Jo Reynolds, who has articulated a desire for art to intervene directly in injustice rather than to reflect or represent. Putting you alongside Tania, Simone, and Laurie Jo underscores how so much of this kind of art is taken up by women; do you think that there is an implicit (or explicit) feminism central to this type of practice?

Heffernan: I much prefer Bruguera’s term “useful art,” because it eschews grand claims, because it’s nimble; it conjures labor that is not estranged from art. I hugely admire Simone Leigh’s Free People’s Medical Clinic for entwining culture, health, and medicine and Laurie Jo Reynolds’s work taking on brute public policy with a kind of strategic aesthetic acupuncture, evoking prisoners’ images from words so that the reader beholds “the Other” in their minds—a mental version of the face-to-face encounter.

This mode of art is absolutely informed by feminist strategies as it takes on state power, authoritarianism, the prison industrial complex, the apartheid past and present of American medicine, and an establishment that deracinates culture from medical care and privileges technology and profit at the expense of much else. I am finding tremendous pleasure and power in the collective work of the PPE Portrait Project (the project leaders, and a majority of the project adopters, are women). Interestingly, we just received a punctum, a tiny signal, in the recent project data that a few male providers noted they didn’t have a “positive experience” with PPE Portraits, even as those commentators reported not having seen them! I’d hazard that there will be a small but notable gendered difference in who adopts and uses the project. It’s designed to level hierarchies and counter the effects of technology. It’s vulnerable-making.

Bryan-Wilson: Social practice, or whatever we call it, is often chastised for being easily instrumentalized by the state. Or for instrumentalizing its participants. Or for instrumentalizing (and subordinating) aesthetic concerns. How do you respond to such critiques? How much does it matter to you that this work is understood “as art”?

Heffernan: These are all valid critiques. Social practice often responds to human needs that should be met by our civic institutions and government, but increasingly aren’t. Do we work for lasting structural change? Of course we do, but sometimes those larger changes begin with small, odd, or poetic (I use this word in the political sense of making language strange to itself) actions. In short: interventions can change social consciousness, spurring changes to the material conditions of people’s lives.

I agree that social-practice art often appears homely! With the PPE Portrait Project, there’s the paradox of a project in which the photograph is central, while the “art” of the project is invisible and thus cannot be “pictured” as such. We can only understand its effects by hearing the narratives of the patients and health-care workers and empathizing with the viewpoint of patients. Picturing the project has been a huge challenge, as HIPAA laws make it extremely difficult for an outsider like me to connect directly with patients. Even documenting the surface of the project for this interview has been a challenge; the image you see from UMass below, of a patient with his palliative care and music therapy providers as he eased into consciousness after a period of sedation on a ventilator—the use of this image was sensitively negotiated with the patient, his guardian, biological family, extended caseworker team, doctors, music therapist, and the medical center. They shared the image to advocate for the benefits of patient-centered, humanistic care.

Bryan-Wilson: Can you say more about how your images from this project travel and spread widely, and how they are not always framed as an art project authored by you?

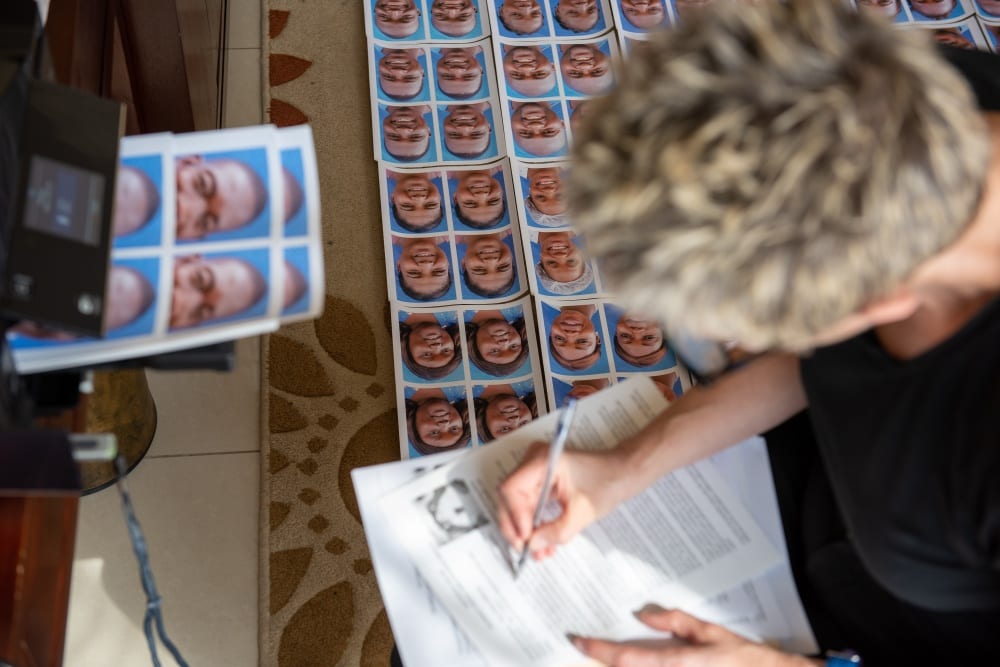

Heffernan: I’ve begun to resent news outlets that want to use the still and video documentation of the project to make splashy, sensationalized, surface-oriented pieces that belie the research, care, trust, and nuanced exchange of the project and its documentation, emblematized by my extensive commitment to garnering informed consent at every level. If you reviewed all the images taken of me in Liberia, half were of me presenting, filling out, duplicating, and handing back provider copies of the informed consent forms. Few request the use of these images—the bureaucratic arts [laughter].

When I created the PPE Portrait Project in 2014–15, I acted to address a pressing need while also keenly considering the ethics of my actions. I reflected on the “art” dimensions of the project in the intervening “quiet phase” of the project. I envisioned this project by tapping the same knowledge base as I did for my other, more recognizably “artistic” productions, and my self-understanding is that this project is art, art in vital conversation with my other art and the larger art community. If I want this project to be recognized as art, it is to be in dialogue with the larger community about what art is, where and how art exists, and artists’ role in society. I’d be kidding myself if I didn’t also admit to having an ego. Designing a project that is contingent on my disappearance has had its rewards, but it’s been a real challenge for me, too.

Bryan-Wilson: Let me pivot to a potentially sensitive but necessary question. How did you approach questions around race, class, and gender when you went to Liberia? I guess I’m especially interested to hear about what I know was your deliberate and self-conscious framing of yourself as a white woman from the US making an intervention in an African country.

Heffernan: I was deeply uneasy with the reality of me being a privileged white woman seeking to “humanize” the experience of Ebola care in Liberia. I rallied the funding, social capital, and agency to make the project happen in a way that would not have been possible for most in Liberia. I had the choice: avoid this deeply discomforting position by staying at home and tweeting the question that ran through my head, “Why don’t they put pictures on the front of the hazmat suits [to make them less frightening]?” Or: grapple with the ethical dimensions of my position, and the project, and try to advance it in as responsible a way as possible. Performing the PPE Portrait Project in response to the Ebola epidemic was a swift object lesson in all of the challenges and problematics of international aid—just as COVID responses have laid bare the deep structural inequalities, particularly along racial lines, in the US.

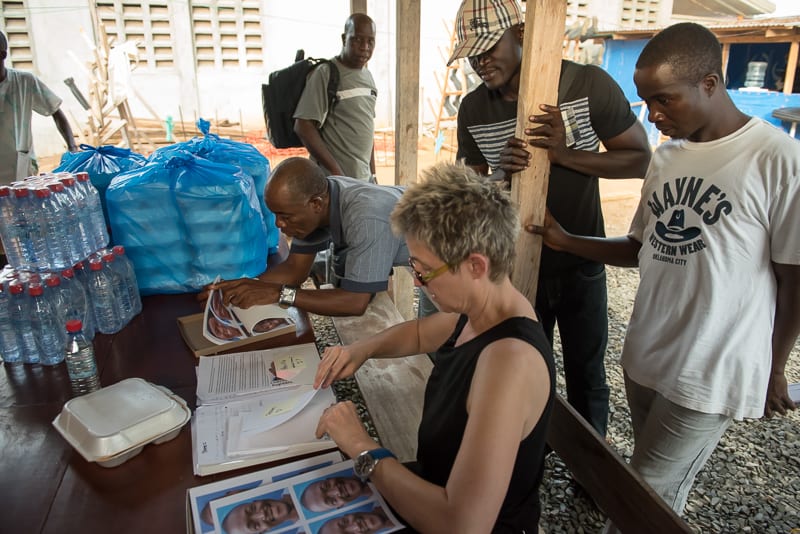

I managed to correspond directly with a few of the Liberian doctors in charge of the Ebola response, including those on the ground serving directly in the Ebola treatment units. Dr. J. Soka Moses, a dynamic young doctor directing the largest Liberian Ebola treatment center, called the proposal a “brilliant idea” and affirmed that the psychosocial component was a major factor in helping patients survive. He said he and his staff would enthusiastically adopt the project. Dr. Moses Massaquoi, then chair of Ebola case management, quickly followed with an invitation to bring the project to Liberia. In January of 2015, the worst of the epidemic was behind them, but he invited me to partner with them to bring the project to the remaining Ebola treatment units and to build capacity for future epidemics. Dr. Jerry Brown was instrumental in setting me up at the Liberia-run ELWA 2 Ebola Treatment Unit. The project would not have come to fruition if not for the invitation from Liberian health leaders and the collaboration of doctors, nurses, physician assistants (PAs), and hygienists providing direct care. I was told by a staffer at the CDC that working directly with the Liberian government was the “gold standard” of engagement.

I was always mindful about the mandate to not only respond to an existing need but to build future capacity. I trained staffers at each site to take over the PPE Portrait Project, and left cameras, printers, and supplies to last until the end of the epidemic. When I left Liberia, I committed to creating a PPE Portrait Project that was sustainable and achievable with local means.

About a month after I returned from Liberia, Bernice Dahn, MD, then chief medical officer of Liberia’s Ministry of Health, cowrote a searing opinion piece in the New York Times about European researchers who, in 1986, published evidence that Ebola antibodies had been found in frozen blood samples of Liberian rubber plantation workers collected in 1978–79, suggesting that an Ebola reservoir was well established in communities decades before the country’s “patient zero” emerged in 2013. Dr. Dahn condemned the lack of Liberians on the research team and the obfuscation of what should have been a call to action, buried in the Annales de l’Institut Pasteur/Virologie. She likened the Germans’ virology research in Liberia to the neocolonial extractive capitalism of the American rubber industry there.

Bryan-Wilson: How did the PPE Portrait Project fit into this dynamic?

Heffernan: I asked myself that very question. Was I partnering with Liberians and leaving knowledge and practices that could develop future capacity there? Would this knowledge and practice be valid if I didn’t also manage to devise a locally produced model or figure out how to finance it in perpetuity? Was I experimenting on Liberians and extracting that knowledge for the current benefit of COVID patients in the US, Canada, and Europe?

I managed to meet Dr. Dahn and briefly present the PPE Portrait Project after the weekly Incident Management System meeting at the National Ebola Response Center in Monrovia, Liberia. She looked at the photo of a nurse in full hazmat gear wearing a PPE Portrait I had pulled up on my iPad, pointed to it, and said, “This is good.” I later learned from a physician tasked with revising the Ebola Treatment Unit (ETU) Operation Manual that was put together at the height of the epidemic that he found a recommendation in the original manual that read: “Facilitate patients’ ability to identify staff (examples: staff have legible names/pictures that clearly identifies them).” He wrote, “As it appears, your contribution addresses a real need that has been noted before, but no one found a solution as good as the one you came up with.” Dr. Dahn’s comment, coupled with the existing ETU protocol that called for an effort to picture the faces inside the hazmat suits, affirmed the PPE Portrait Project’s beneficial capacity for, and ethical engagement with, patients and providers in Liberia.

Bryan-Wilson: Are you still in touch with those providers?

Heffernan: Yes, I am in contact with the doctors, nurses, and hygienists/cleaners who were instrumental in bringing the PPE Portrait Project to fruition there. A number of them are now working at a COVID clinic, once again at great risk to themselves. Are they using PPE Portrait labels now? I was dispirited, but not surprised, to learn that they are not. The focus has been on sourcing and rigorously using the PPE itself, not dissimilar from the challenges here in the US.

Together, we are strategizing about how to fulfill the aims of the PPE Portrait Project with different means. For example, smartphones are far more widely available than they were five years ago. We discussed the possibility of providers placing their phones in clear plastic bags and sharing their selfies with patients. This is an adaptation of how some US hospitals are “introducing” the doctors and nurses on patients’ medical teams.

In addition to the granular adaptation above, I am also playing a long game. I believe that aiming to make PPE Portraits best medical practice (where full face-shield PPE is not used and patients primarily see their providers in masks) is the strongest, most sustainable path to making them the standard of care for everybody, everywhere.

Bryan-Wilson: One additional challenge to this project is that you pursued informed consent for everyone involved, including patients. This is its own ethical stance. Can you talk about the complications involved in this choice?

Heffernan: I earned Human Subject Research Committee/Institutional Review Board approval for the project and its documentation and sought informed consent for participation in every aspect of the project. Health-care workers had the choice to not participate, to participate but not be recorded while using the PPE Portraits, or to participate and be documented with photographs and video. The patients who we photographed inside the “red zone” of suspected and confirmed cases were first approached for informed consent by the health-care workers only if they were deemed well enough to engage with the process. This is why there are so few images inside the red zone; that, and the considerable risks Marc Campos, our documentarian, assumed by going into that zone.

When we learned that a European news crew (who worked freely without seeking informed consent) had swooped in to take images of the spectacle of the sick and dying and was sharing nothing in return, we left Dr. Brown with a drive of every image and video segment we recorded during our stay for their records and use. I’ve stayed in touch with the health-care workers, and when the project was curated in the ten-year exhibition Being Human at the Wellcome Collection that opened last September, I included the first-person narratives of each participating health-care worker so that they would be represented by their own words and not just by their images. I also worked to find a way to transform my cultural and social capital around this project into a modicum of economic capital for the participants (without violating the terms of the informed consent form that we both signed) by sending each participant a significant honorarium for this new representation of the project.

Bryan-Wilson: Returning to questions of power, would you like to say more about how hierarchies and structural inequalities manifested around, and inextricably shaped, this work?

Heffernan: Are there still unequal power relations along the lines of race, class, and gender? Unfortunately, yes. I have worked hard to honor the project as a collaboration with tremendous respect for my partners’ expertise, critical feedback, and dedication to their profession and country. It’s a very difficult balance when the economic gulf persists. This work needs to be done with extreme deference to partner autonomy and aim for an exchange of knowledge.

I have a wonderful role model in the founding codirector of EqualHealth, Michelle Morse, MD, who is also cofounder of the Social Medicine Consortium, dedicated to global health equity and “committed to engaging in humble relationships that recognize our limitations and privileges, acknowledging pervasive historical injustices and pursuing collective liberation through shared struggle. We seek proximity to suffering and create coalitions that transcend traditional lines of power, and utilize disruptive activism to redistribute power and center marginalized voices.” She has invited me to write the story of the PPE Portrait Project as a case study to teach global health and social medicine principles and the struggle to engage ethically across difference.

Bryan-Wilson: Art historian Sarah Lewis recently wrote a piece for the New York Times about the lack of photographs of COVID-19 victims, “Where Are the Photos of People Dying of Covid?” She notes that the primary visualization of the disease has been of the spiky virus molecule rather than human suffering, which has the effect of making the pandemic seem somewhat abstract. Your project is compelling within the history of photography because you grasp that there are multiple points of perspective at issue here—that it matters not just how the world views the patient (as mediated through the photograph) but also, crucially, how the patient sees the caregiver (thanks to you, as mediated through the photograph).

Heffernan: I actually reached out to Dr. Lewis, thanking her for this piece calling for a more substantive iconography of the pandemic. The viewpoint and experience of the patient is finally coming into the consciousness of the larger public. Patients’ suffering is multifold: the terrifying experience of the disease, shame about potentially infecting one’s caregivers, and the depredations of being isolated while sick. We are witnessing COVID’s disproportionate effects on the African American and Latinx communities. Congresswomen Ayanna Pressley, Karen Bass, Robin Kelly, and Lauren Underwood proposed the Equitable Data Collection and Disclosure on COVID-19 Act that would give us important information to identify and focus responses and resources where they are needed most. However, it is often the affect generated by images, not numbers, that spurs people to act. All of this is why the pictures, and the stories, of patients and health-care workers need to be made visible and heard.

Bryan-Wilson: In some ways, your project asks fundamental questions about the nature of the photographic portrait. Does it demand proximity? And how is that proximity navigated during a moment when maintaining physical distance is paramount?

Heffernan: Portraits play many roles; some confer status and are honorific or idealizing, meant to establish distance; others are gifts, offerings conferring a bond. I wish to catalyze the latter, so that in the absence of physical proximity, we tender a visual intimacy. The PPE Portrait Project acts as a bridge across physical distance, a sight line that is also a lifeline, an offering instantiating a shared humanity.

Bryan-Wilson: Your work has touched a nerve during the COVID-19 crisis, and I know you’ve been inundated with escalating requests and inquiries in the last several weeks. How is the project shifting, perhaps scaling up, given this new level of exposure?

Heffernan: I always hoped that the PPE Portrait Project would become best medical practice, as I came to realize that this is the most effective path to making it an intrinsic part of international PPE protocol. Since the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, I’ve worked to make it available to, say, cancer or immunocompromised patients, anyone who primarily sees their caregivers in masks. In the intervening years it struggled to gain traction, partly because medical institutions are not accustomed to substantively collaborating with artists, and also because there was no perceived urgency for its need. Now interest has exploded to the point that all manner of people are practicing versions of it (and even claiming to have invented it!). This has been incredibly exciting but also disorienting, especially to hear others utter my words and phrases, use my project name without credit or images without permission, or make alterations that violate the infection control standards I worked hard to establish in consultation with case management physicians.

My aim now is to establish best medical practice standards for the project (which has been my commitment from the start) and to expand the project with institutional partners in a way that is robust and sustainable. I’m working closely with an impressive care improvement and implementation researcher at Stanford Medical School, Cati Brown-Johnson, PhD, and the MIT-trained digital user experience professional and photographer Paige K. Parsons. I’m relieved that they handle work outside my wheelhouse: Cati does the kind of research that evidence-based medicine demands. Remarkably, she finds the human story in the numbers. (We just published our first manuscript in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.) Paige organizes volunteer photographers, tests materials, and is setting in place larger structures and workflows to streamline the project for sites with variable needs. There is also the wise Stacie Vilendrer, MD, who is serving as our medical director, and a group of insightful postdoc researchers supporting the project at Stanford. We see my role as honing the standards and vision of the project and shepherding it into the future.

Bryan-Wilson: How are you thinking about continuing your labors, or maybe having them evolve, as you project into the future and imagine where this work might take you?

Heffernan: I am refocusing my efforts on the essence and ethics of the project, which are bound up in its aesthetics and performative dimensions. How can it retain, as it becomes institutionalized, the quietly radical proposition of shoring up a patient’s agency in their time of need? Of lessening hierarchies and reducing the alienation between patient and caregiver, and among caregivers themselves? I want to think more deeply about the power of the portrait and imaging, especially vis-à-vis bodies that are otherwise invisible—an ongoing theme in my work. I also want to return to the other founding inspirations for the project, the patient narratives and, if I’m able, the patients themselves, who are the sine qua non of the project. I think there is more to learn, and art to come of it all.

Julia Bryan-Wilson is the Doris and Clarence Malo Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at the University of California, Berkeley, and director of the UC Berkeley Arts Research Center. She is also an adjunct curator at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo.

Mary Beth Heffernan is a Los Angeles–based artist whose work explores the interplay of corporeality and images. She is professor of art at Occidental College. Heffernan’s work is in the collections of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California; Hammer Museum Grunwald Center Collection, Los Angeles; and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.