From Art Journal 79, no. 2 (Summer 2020)

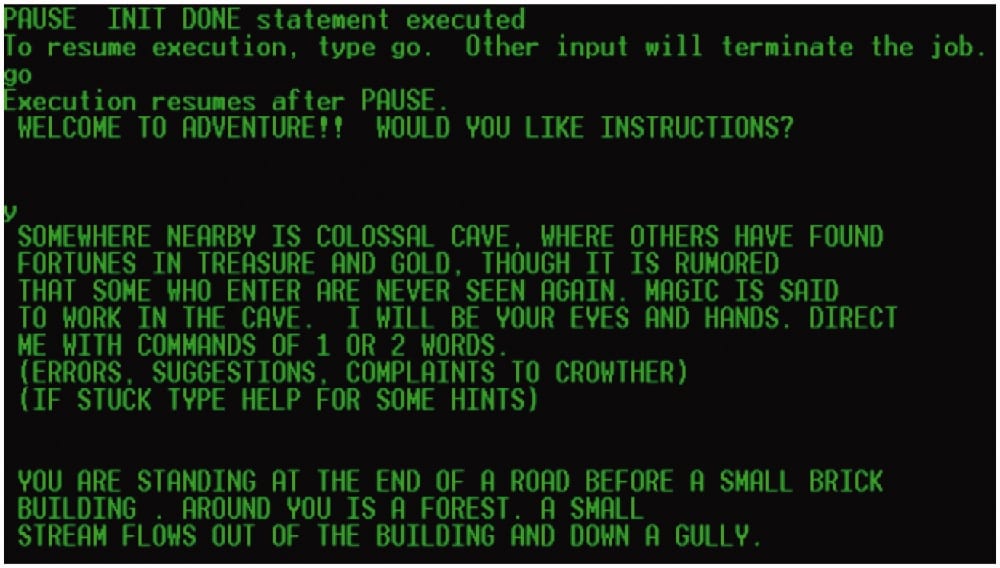

“YOU ARE STANDING AT THE END OF A ROAD BEFORE A SMALL BRICK BUILDING. AROUND YOU IS A FOREST. A SMALL STREAM FLOWS OUT OF THE BUILDING AND DOWN A GULLY.”

So begins Adventure, developed by computer programmer William Crowther in 1975.1 Adventure was the first interactive text-based video game of its kind, and initiated the “adventure” genre, which focuses on puzzle solving, collection of in-game resources, and exploration of terrain.

From the beginning, in its phosphor green, text-only form, Adventure’s conjuring of a rich and evocative world designed for the player-hero’s quest demonstrated how fundamental landscape is to the game experience. And even in the earliest video graphics–based games like Tennis for Two (1958) and Spacewar! (1961–62), spatial representation played a predominant role. In the first case, a tennis court is rendered in profile. In the second, a two-person torpedo-battle takes place in an interstellar space with a central gravitational pull. Although the budgets for major video games now rival those of the Hollywood blockbuster, and their rendering capacities far exceed what could have been envisioned in their humble beginnings, the central function of landscape presaged in Crowther’s iconic Adventure remains.2

This special focus of Art Journal examines the world making of video games from aesthetic, art historical, and visual studies perspectives, as a way of bringing to the fore an elemental component that might normally be conceived of as the mere “backdrop” upon which game-based adventures occur. In fact, as forms of visual culture, video games are intentional in their construction of a particular experience, and as with the landscapes of painting, photography, and cinema, they too make claims about land, space, and place.3

The research here developed out of the first dedicated panel on representation in video games to be presented at a CAA Annual Conference.4 As the moderator of the dialogue, I was struck by the fact that, although the medium is now more than sixty years old, within art history/visual studies there remains a critical neglect of games as legitimate objects of study. A critical and methodological deadlock exists in which both games studies and the history of art/visual studies are intellectually uninterested in one another. Art history and visual studies have not substantively engaged with video games, tending to view the form as pure escapism, as a hyper-capitalist enterprise, or as training tools for militarism and violence.5 At the same time, despite the fact that games are predominantly image based, critical game studies rarely turn to the methodological approaches of art history or visual culture studies. These are troubling forms of disciplinary inaction that, as I have argued elsewhere, contribute to the persistence of problematic image-making practices that pervade mainstream games.6 The games industry is not substantially held to account, and this is at least in part due to the absence of robust critical frameworks for articulating some kind of complex engagement with the visual culture of video games. Art history and visual studies may in fact possess one of the most effective critical tool kits for addressing these concerns, particularly in terms of the close reading of the image in its context.

The contributors present generative possibilities for how such an examination of video games might be undertaken, from the perspectives of art historical research, speculative writing, creative practice, critical conversation, and a manifesto. Games present universes of visual culture as yet greatly neglected by scholars of art—though certainly not by creative practitioners. The articles included here serve as an invocation to art historians and visual studies scholars, who have much expertise to offer in this regard—if we will only venture into the territory. My initial interest in video games has grown to become more capacious than the original panel’s focus on representation. And while concerns around race, gender, and sexuality remain central in my work and are increasingly acknowledged in critical game studies, landscape provides a natural touchstone to generate conversation between video games and art history.

Shoshana Magnet first coined the term “gamescapes” in reference to “the way in which landscape in video games is actively constructed within a particular ideological framework.”7 In this way, she articulated the shifting provisional meanings possible in video games, based upon the interplay created between the active participant and the dynamic landscape. And she acknowledged the dimensions of power that bear down on the representations within games, based upon the spatial ideologies generated through the coinvolvement (albeit uneven) of maker, game, and player. With this gesture, Magnet called for an awareness of landscape as ideologically loaded and then mobilized the concept toward greater interpretive potentials.

Within art history, studies of landscape have been a major avenue of sustained engagement—particularly as it relates to painting. Art historians such as Kenneth Clark, Denis Cosgrove, Stephen Daniels, Malcolm Andrews, John Barrell, Ann Bermingham, Jay Appleton, and many others have illuminated the function of such images to engineer and galvanize social, cultural, political, and even ideological perspectives.8 In his discussion of traditional landscape, W. J. T. Mitchell ties the gaze upon the land to “the eye of a predator who scans the landscape as a strategic field, a network of prospects, refuges and hazards.”9 Though he references conventional landscapes and not game spaces, Mitchell’s words invoke a kind of looking that recalls the opportunistic eye of the shrewd player. This formulation suggests an immersive game space that presents itself as innocuous, but that must be carefully observed and understood affectively in terms of what Mitchell calls the “violence and evil written on the land, projected there by the gazing eye.”10 These are loaded words, but nevertheless applicable to the intensity with which playable simulations of space may become increasingly overdetermined by cultural imperatives.

Video games encourage the observation and exploitation of everything within a game space in terms of potential use-value for the player. This is because, as anyone who plays video games knows, a player is engaging with a rule-based system. Part of playing video games involves learning how to maneuver within the rules, how to master them, and even at times how to break or purposely cheat system limitations.11 Playing with conventional game systems—oriented toward rewards, strategies, and missions—often encourages an opportunistic and exploitative form of observation. This predatory viewing is not limited to excessively masculinized displays in games like military shooters, since there are many forms of games that demand effective use of space. Already in the mid-1990s, scholars were beginning to understand the ways in which video games repeated narratives of the mastery of space, connecting play with ideologies deeply embedded within the cultural imagination. For example, in their 1995 coauthored text, media scholar Henry Jenkins and literature scholar Mary Fuller explored connections between power narratives of exploration and colonization in New World documents and their symbolic repetition in video game spaces. Jenkins writes:

Nintendo® not only allows players to identify with the founding myths of the American nation but to restage them, to bring them into the sphere of direct social experience. If ideology is at work in Nintendo® games (and rather obviously, it is), ideology works not through character identification but, rather, through role playing. Nintendo® takes children and their own needs to master their social space and turns them into virtual colonists driven by a desire to master and control digital space.12

We may think of the game space—that is, the already mediated site of the video game that manifests through a second mediation of playable engagement—as encouraging particular kinds of approaches to its spaces. John Sharp, a game designer and art historian, has observed: “The space of possibility within a game is all potential, a potential realized through play. Games, when approached with artistic sensibilities, explore an aesthetics located somewhere between the conceptual and the experiential.” 13 More recently, critical game studies scholars like Souvik Mukherjee have enhanced and expanded the work of Jenkins and Fuller into a more robust conversation about games and neocolonialism, drawing upon theories of postcolonialism to counter the most cloying stereotypes of the non-West.14

From the moment digital technology permitted even the most rudimentary spatial representations, games scholars and new media theorists have identified the significance of video games’ world-making properties.15 An ongoing conversation has ensued between esteemed digital media scholars including Janet Murray, Lev Manovich, Espen Aarseth, and others, but largely without contribution from the arts—despite the obvious connection to landscape as ideology.16 Jenkins has described video games as spatial stories, “pushed forward by the character’s movement across the map.” Telling these stories well becomes about “designing the geography of imaginary worlds, so that obstacles thwart and affordances facilitate the protagonist’s forward movement towards resolution.”17

To be sure, these are all meaningful interventions, but also startlingly devoid of useful methods, practices, and the rich bodies of knowledge that art history and visual culture studies have refined. More importantly, video games borrow heavily from earlier forms of visual culture like television, art, and especially cinema, often relying on those preexisting visual languages to cue the player using familiar signifiers. For example, the Rockstar Games action-adventure Red Dead series (2004–present) remediates the Western genre, inserting the player into the American Old West film—revisiting frontier mythologies in the process. Critical game studies is necessarily transdisciplinary. Still, games are not merely a technological enterprise—in their complex image-making practices, video games function as loaded cultural texts as well.

Geography scholar Michael W. Longan examines the simulated terrains of games as mirroring aspects of the lived world, calling them a form of “landscape representation that communicates ideas about how the world is and how it should be.”18 He boldly proposes that game landscapes contain deeply moral considerations in their very instantiation, and argues that a more robust critical apparatus is necessary to understand them.19 Longan’s work represents one of the few attenuated analyses of landscape and game space, unveiling “often hidden social processes behind the production of real world landscapes” and calling attention to the visual studies–based scholarship around landscape, which takes for granted the already mediated, ideological nature of re-presenting space.20

Video games are complex manifestations, but some would even argue that they are of an altogether different order. Notably, the late, renowned filmmaker and intellectual Harun Farocki described computational images as “strange new images, which are somehow on the verge of competing with and defeating finally the cinematographic, photographic image, so that the era of reproduction seems to be over, more or less, and the era of construction of a new world seems to be somehow on the horizon—or not on the horizon—it’s already here.”21 Farocki, in his last series, titled Parallel I–IV (2012–14), completed what was perhaps the most generative of his late career investigations into the “operational image”—machine images whose effects for human eyes are only by-products of their legibility for machines—which the filmmaker himself believed to be supplanting our access to the real.22 In his suite of four works, Farocki presents the display image (i.e., the simulated computational image) in terms of the natural world and the hero within it, exploring their limits, their architectures, and their status as fundamentally hollow objects.23

Film historian Thomas Elsaesser characterized Farocki’s careful deconstruction of the visual logics of computational images as “the change of default values, so that the digital image is now the primary reference point for all kinds of images, including analogue images.”24 This change of primary reference points is not merely a matter of aesthetics or visuality, to be sure, but a sign that points to shifting ideologies, under whose logics such forms of display make sense. Elsaesser continues:

We suddenly see how Farocki pulls the rug from under the “greater and greater realism” argument, when he shows how with CGI, no matter how “realistic,” there is no depth to the ocean floor, no slope to a hill nor incline to a mountain range, and a forest or an urban street scene can just drop off the edge, disappear or float in space. The world of digital images can serve Farocki as a metaphor because it reminds us that the reality we see and experience everyday may be nothing like the reality that affects our lives and determines our fate. . . . Thus, while the ostensible parallels of Parallel I–IV are between analogue photographs and their digital clones, the more oblique parallels are more pointedly political, in that they suggest the denser the details, the more deceptive the reality.25

Farocki’s recontextualizing the constructed image of the video game into a space for contemplation, such as the gallery or museum, functions to wrestle the simulation from its tendency to present itself as a totalizing work. And in doing so, it becomes possible to see its inner workings. This special focus is about using art history, media studies, and visual culture studies to crack open creative possibilities for understanding gamescapes, with their increasingly dense details and deceptive realities.

Farocki is among innumerable notable artists, including Feng Mengbo, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Cory Arcangel, Phil Solomon, Joseph DeLappe, and Colleen Flaherty and Matteo Bittanti (as the collective COLL.EO), who take seriously the simulated spaces of games as places in which to grapple with some of the most potent questions of our moment. The scholars and practitioners included in this issue of Art Journal contemplate these worlds and their potent simulation of “place” as sites in which a player effectively comes to have an experience of “being there.” What can be made of these worlds? How are they constructed? What do they tell us about ourselves and the world we live in? How might we begin to recalibrate our understanding of the world building that takes place, toward a view of game spaces that function as more than sites of collection, conquest, militarism, and simulated violence?

Eugénie Shinkle, best known for her work as a photographic artist and scholar, presents a brilliant analysis of the connections between Picturesque landscape aesthetics and the intentional design of game spaces. She effectively traces the cavernous gulf between so-called “naturalistic” representation and simulated environments. Her intervention can be considered within the context of conversations like those of Magnet, Jenkins, Fuller, and Longan, though it certainly pushes that conversation in new directions. Her assertive position, that the questions raised by the Picturesque garden are deeply ontological, may seem like an acceptable move within art historical analysis, but it is certainly not a given within the dominant discourses of video games. Contesting the notion of gamescapes as mere representations of landscape, Shinkle offers fresh and urgent theoretical possibilities for players as active agents in the shaping of their own relations to nature, both inside and outside game space.

Connecting to this fraught conversation around the representation of nature in video games, media studies scholar Alenda Y. Chang contributes a manifesto rooted in her concern with eco-critical scholarship and games.26 In her thought experiment, she sets forth a series of provocations for the conscientious game designer to consider when creating environmentally intelligent game spaces.27 With her background in biology, literature, and film, Chang playfully draws together the threads of ideology, politics, ecology, and game studies into a clear-eyed set of practical tools for artists and designers who wish to break from conventional, exhausted paradigms and embrace principles altogether more rambunctious.

Scholar Hava Aldouby excerpts her sustained dialogue over many years with artist Phil Solomon, who since 2005 had made experimental films using games like Grand Theft Auto (GTA), playing “against the grain” of their intended purpose. In conversation, they explore how Solomon teases new meanings from GTA’s impressive spaces, maximizing the friction between, as he describes it, “elegiac narratives” and “the obvious artifice of pixels and polygons that make up that world.” Solomon’s untimely passing in April 2019 came as a shock, and the excerpted conversation here represents what is likely the filmmaker’s last interview. His experiments with game-based filmmaking and his ability to push the space into new signifying potentials continues some aspects of Farocki’s investigations. And his astute observations on the experiential dimensions of what it means to sustain one’s self in simulated space provide insight into some of its unique properties and opportunities.

Scholar and practitioner Dorothy R. Santos explores biotechnology and cyberfeminism in her analysis of three alternative video games by women who directly engage with bodies as metaphors for place, and of the fraught experience of women’s bodies in spaces of the lived world. Santos’s work represents the vanguard of thinking about the future of games as personal, political, and interventionist. Her commitment to inclusivity in games has gathered energy in both mainstream and especially alternative game design, as a response to a pattern of ugly and ongoing harassment of women, people of color, and gay, trans, and nonbinary individuals in the games industry and its ancillary cultures.28 In the wake of a fraught and public surfacing of those intolerances, Santos draws attention to several artistic projects by game designers who subvert and resist with great humor and verve. The larger notion that games, as game designer Anna Anthropy noted, are good at “forcing the player to inhabit a political ideology” is incredibly relevant to understanding their potent visual rhetorics within the context of their space-making functions.29 Bringing this conversation full circle, Santos also contributes a text-based interactive work that captures the spirit of the original choose-your-own-adventure type of video games, presented here in print throughout the pages of this issue, as well as in dynamic form, playable through Art Journal Open.

Finally, respected experimental game designer and scholar Tracy Fullerton presents her celebrated and innovative Walden, a game, a first-person simulation of Henry David Thoreau’s experiment in living at Walden Pond. Ten years in the making, Walden was released in 2017 by the USC Game Innovation Lab, directed by Fullerton. Since then, Walden has been shown in game design and art contexts and has been awarded for its originality and departure from convention. The game encourages reflective play rather than conventional strategic challenges and the cultivation of twitch responses. Organized around the narrative of Thoreau’s original text, Walden provides a contextual experience of self-reliance and living in balance with nature. Through core game-play elements of collecting necessities and the maintenance of shelter and clothing, as well as contemplative rambles through nature, Walden gently encourages the player to slow down. It provides a meaningful and pathfinding example of what games can be, and does so by mobilizing its spaces toward a very different purpose from mainstream commercial expectations. Retracing her own experience through the spaces of Walden, Fullerton presents insights into her engagement, in the unlikely form of a personal travelogue recounting her passage through the game.

This special focus is bookended by two artist’s projects: an homage to Harun Farocki’s Parallel series, and COLL.EO’s The Long Road of Silicon. Together, these works provide access points to a rich and varied set of antagonisms, conversations, provocations, and negotiations taking place in video games. As highly creative visual, aural, and tactile forms, video games engage their players in aesthetically meaningful ways, and open up new possibilities for how we might understand and experience space. With this focus, contributors invite greater participation by scholars of art history and visual culture in this vibrant conversation around a form of expression that has been so influential on culture at large and that deserves far more critical attention from the arts. As Farocki declared, the simulated spaces of games herald new paradigms and indicate new horizons that are, in fact, already here. Farocki pointed the way but could only begin to investigate these navigable spaces. This project stands as a thought experiment in what some of those possible horizons might be.

Soraya Murray is an associate professor in the Film and Digital Media Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her writings are anthologized and may be found in Art Journal, Third Text, Film Quarterly, and Critical Inquiry. Murray’s book, On Video Games: The Visual Politics of Race, Gender and Space (I. B. Tauris, 2018), considers video games from a visual studies perspective.

- This game is also known as Colossal Cave Adventure. ↩

- For an excellent consideration of the connection between Adventure and the Mammoth Caves in Kentucky, which inspired the game, see Alenda Y. Chang, “Games as Environmental Texts,” Qui Parle: Critical Humanities and Social Sciences 19, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 2011): 57–84. ↩

- I explore this in depth in my book, On Video Games: The Visual Politics of Race, Gender and Space (London: I. B. Tauris, 2018), esp. chaps. 3 and 4. ↩

- “The Visual Politics of Play: On the Signifying Practices of Digital Games,” Soraya Murray, org. (session, CAA Annual Conference, Washington, DC, Feb. 2016). ↩

- Examples of scholarship on video games from an art historical perspective include John Sharp and David Thomas, Fun, Taste, & Games: An Aesthetics of the Idle, Unproductive, and Otherwise Playful (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019); John Sharp, Works of Game: On the Aesthetics of Games and Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015); Brian Schrank, Avant-Garde Videogames: Playing with Technoculture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014); and Raiford Guins, Game After: A Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014). ↩

- Murray, introduction to On Video Games, 1–46. ↩

- Shoshana Magnet, “Playing at Colonization: Interpreting Imaginary Landscapes in the Video Game Tropico,” Journal of Communication Inquiry 30, no. 2 (April 1, 2006): 142–43, https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859905285320. ↩

- Kenneth Clark, Landscape into Art, 2nd rev. ed. (London: John Murray, 1979); Denis Cosgrove and Stephen Daniels, eds., The Iconography of Landscape: Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design and Use of Past Environments (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988); Malcolm Andrews, Landscape and Western Art, 1st ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999); John Barrell, The Dark Side of the Landscape: The Rural Poor in English Painting, 1730–1840 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983); Ann Bermingham, Landscape and Ideology: The English Rustic Tradition, 1740–1860 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989); Jay Appleton, The Experience of Landscape (London: John Wiley, 1975). ↩

- W. J. T. Mitchell, “Imperial Landscape,” in Landscape and Power, ed. Mitchell, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 16. ↩

- Ibid., 29. ↩

- See Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003); Jesper Juul, Half-Real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005); Mia Consalvo, Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009); Bonnie Ruberg, “Playing to Lose: The Queer Art of Failing at Video Games,” in Gaming Representation: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Video Games, ed. Jennifer Malkowski and TreaAndrea M. Russworm, Digital Game Studies (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017), 197–211. ↩

- Mary Fuller and Henry Jenkins, “Nintendo® and New World Travel Writing: A Dialogue,” in Cybersociety: Computer-Mediated Communication and Community, ed. Steven G. Jones (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1995), 72 ↩

- Sharp, Works of Game, 106. ↩

- Vit Šisler, “Digital Arabs: Representation in Video Games,” European Journal of Cultural Studies 11, no. 2 (2008): 203–20; Johan Höglund, “Electronic Empire: Orientalism Revisited in the Military Shooter,” Game Studies 8, no. 1 (September 2008); Sybille Lammes, “Postcolonial Playgrounds: Games as Postcolonial Cultures,” Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture 4, no. 1 (2010): 1–6; Souvik Mukherjee, Videogames and Postcolonialism: Empire Plays Back (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017). ↩

- See Mark J. P. Wolf, Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation (New York: Routledge, 2012). ↩

- Janet Horowitz Murray, Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1997), esp. 79–83; Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002); Espen Aarseth, “Allegories of Space: The Question of Spatiality in Computer Games,” in Cybertext Yearbook 2000 (Jyvaskyla, Finland: Research Centre for Contemporary Culture, 2001), 152–71. ↩

- Henry Jenkins, “Game Design as Narrative Architecture,” in First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game, ed. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 124–25. ↩

- Michael W. Longan, “Playing with Landscape: Social Process and Spatial Form in Video Games,” Aether: The Journal of Media Geography 2 (April 2008): 23. ↩

- Longan especially references: Denis E. Cosgrove, Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998); Cosgrove and Daniels, The Iconography of Landscape. ↩

- Longan, “Playing with Landscape,” 24–25. ↩

- Harun Farocki: Cinema, Video Games and Finding the Detail, TateShots (London, 2016). ↩

- See Volker Pantenburg, “Working Images: Harun Farocki and the Operational Image,” in Image Operations: Visual Media and Political Conflict, ed. Jens Eder and Charlotte Klonk (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2017), 49–62. ↩

- See Thomas Elsaesser, “Simulation and the Labour of Invisibility: Harun Farocki’s Life Manuals,” Animation 12, no. 3 (November 2017): 216. ↩

- Ibid., 218. ↩

- Ibid., 221. ↩

- Alenda Y. Chang, Playing Nature: Ecology in Video Games (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019). ↩

- Mary Flanagan and Helen Nissenbaum, Values at Play in Digital Games (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014). ↩

- See Shira Chess and Adrienne Shaw, “A Conspiracy of Fishes, or, How We Learned to Stop Worrying About #GamerGate and Embrace Hegemonic Masculinity,” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 59, no. 1 (March 2015): 208–20; Brianna Wu, “Rape and Death Threats Are Terrorizing Female Gamers: Why Haven’t Men in Tech Spoken Out?,” Washington Post, October 20, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2014/10/20/rape-and-death-threats-are-terrorizing-female-gamers-why-havent-men-in-tech-spoken-out/; and Bonnie Ruberg and Amanda Phillips, “Not Gay as in Happy: Queer Resistance and Video Games (Introduction),” Game Studies 18, no. 3 (December 2018), http://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/phillips_ruberg. ↩

- Anna Anthropy, Rise of the Videogame Zinesters: How Freaks, Normals, Amateurs, Artists, Dreamers, Dropouts, Queers, Housewives, and People Like You Are Taking Back an Art Form (New York: Seven Stories, 2012), 122. ↩