From Art Journal 79, no. 3 (Fall 2020)

It is so seamlessly woven into the fiber of our lives that to pull at that dangling thread of inequality is to rip open an entire life.

—Cherríe Moraga1

The thread is frequently evoked as a metaphor for connectivity as well as precarity. In a memoir dedicated to her mother, Cherríe Moraga uses it in both senses. The thread to which she refers is one among many that constitute the fabric of a life in which oppression and inequity are integral and binding. The peril of the dangling thread lies precisely in its inextricable relation to the whole. A metaphor for the minoritarian subject, it suggests a state of perpetual risk of undoing, extraneousness, and vulnerability. The intergenerational transborder story Moraga narrates in Native Country of the Heart (2019), one she describes as a “thickly braided cord,” is laden with the tactile. The touches, blows, and caresses exchanged among family members, lovers, and friends gain meaning only in relation to the raced, sexed, and gendered particularities of bodies whose identities are negotiated through and, in some instances, in spite of the colonial context in which they are situated. For Moraga, this is life lived on both sides of the Mexico-US border.

Moraga’s metaphorical thread has a material counterpart in the work of Mexican American artist Margarita Cabrera, whose soft sculptures deploy the haptic as a visual register—what Laura Marks terms “haptic visuality”—in order to make perceptible processes of production as they pertain to the objects themselves as well as to the subjectivities of those who created them.2 In 2001 the artist began creating a series of hand-sewn vinyl objects, among which are a blender, vacuum, coffeepot, and bicycle. The sculptures are to scale, yet their pastel colors and pliable surfaces render them strange. Seemingly ever on the verge of collapse, the vinyl buckles and folds. Long, hairlike threads hang from the seams of the sculptures, a recurrent feature of Cabrera’s work. The falling strands render hypervisible the handmade manufacture of the sculptures, as do the irregularities of their forms. These corporeal resonances of Cabrera’s sculptures register not only the hand of the artist but also the touch of disposable minoritarian labor, precisely that which the hard, shiny plastic of the mass-manufactured objects they resemble erases.

When read alongside Moraga’s textural metaphors, these excessive extensions appear to offer seemingly endless opportunities for undoing, a kind of haptical precarity that signals what Fred Moten and Stefano Harney name the “touch of the undercommons.”3 The anthropomorphic sensuality of the sculptures’ folds, bulges, and hairlike threads proposes an elision between the disposability of the commodity and that of the labor used to produce it. Informed by Moten and Harney’s notion of hapticality, Rizvana Bradley describes the haptic as the “viscera that ruptures the apparent surface of any work, . . . the material surplus.” The dangling threads of Cabrera’s soft sculpture are just such a surplus, one that, to use Bradley’s words again, could be said to index “an explicitly minoritarian aesthetic and political formation.”4

This essay examines the multiple modes through which the haptic qualities of Cabrera’s Space in Between (2010–) negotiate identity as it is shaped in relation to the Mexico-US border as a physical site, a psychology, and a cipher for the production of colonial as well as decolonial imaginaries. Through her use of craft and the aesthetic resonances of the handmade with which it is so readily associated, the soft sculptures that have resulted from the various iterations of this community-based project disrupt colonial constructions of the gendered and raced immigrant body. The languishing threads and uneven raw textile edges that characterize Space in Between are “haptic tactics” deployed by the artist as a means to move beyond optical relationality toward an affective intersubjective sensing.5 The tactical quality of this approach lies in its ability to counter, if not momentarily subvert, the violent touch to which bodies deemed deviant are readily subjected. Haptic tactics can register the ways in which nonnormative or colonized bodies are positioned as excessive in their corporeality, a relation of objectivity that justifies regulatory containment and detainment while, simultaneously, offering touch of another order.

Shortly after earning her MFA at Hunter College in New York in 2001, the Mexican-born and Texas-raised Cabrera returned to west Texas as an artist-in-residence at the Border Art Residency in El Paso, where she began creating the soft sculptures noted above. The series developed from the artist’s interest in maquiladoras, factories on the border that are notorious for their deplorable working conditions and low wages. Like the labor of craft signaled in the overt handmade-ness of the sculptures, industrial labor at the border is feminized, something that the domestic associations of Cabrera’s household appliances and their pastel hues denote as well.6 Cabrera describes the sculptures as “unfinished, forgotten, worn out.” They are, she continues, “visual metaphors that reflect the physical and psychological effects of living along the Mexican border.”7 Much of Cabrera’s subsequent work has involved expanding her practice to incorporate the perspectives and creative input, as well as labor, of folks residing in largely immigrant communities. Invested in transforming, rather than merely commenting on, the ways immigration policies, labor injustice, and cultural production shape identity and perceptions of people migrating from the global south northward, Cabrera has orchestrated projects at art galleries, community centers, college campuses, and botanical gardens, among a range of other sites.

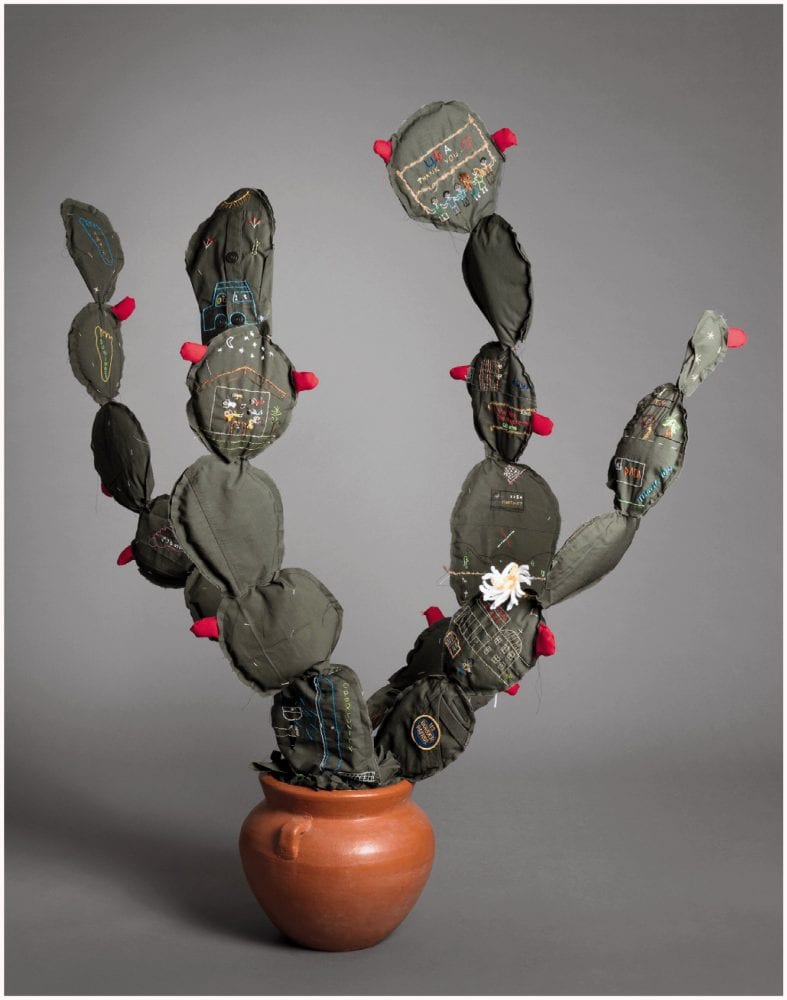

In 2010 Cabrera hosted the first of a series of community workshops for Space in Between, a project that has two primary functions. The first is to bring together largely Spanish-speaking immigrant communities to share in their transborder experiences while gaining access to the knowledge, space, and materials necessary to create art about them. The second is to educate workshop attendees and, later, exhibition viewers on Otomí sewing and embroidery techniques from Los Tenangos, Hidalgo, Mexico. Traditionally sewn on muslin, the vibrant pictographic iconography of Otomí embroidery commonly includes both figurative representations of animals, plants, and humans and intricate geometric patterns that evidence the time- and skill-intensive nature of the technique. Provided with fabric, needles, thread, sewing machines, wooden hoops, and shears, the participants embroider their unique images onto fragments of former US Border Patrol uniforms. The distinctive olive green fabrics are stitched together, pulled over bent wire frames, and stuffed to create the shapes of various desert plants, including agave, nopal, and saguaro. “Planted” in terra-cotta pots, the resulting works range from squat bisnagas that rise only two feet from the floor to lean, seven-foot-tall barrel cacti.

Cabrera’s use of the consignment-patrol uniforms recalls Tomás Ybarra-Frausto’s notion of rasquachismo, which he described as “the aesthetic sensibility of los de abajo, of the underdog.”8 The innovation and subversiveness that characterize rasquachismo is a product of an ability to “thrive” in the face of systemic oppression. As Amalia Mesa-Baines describes: “Aesthetic expression comes from discards, fragments, even recycled everyday materials such as tires, broken plates. . . . In its broadest sense, it is a combination of resistant and resilient attitudes devised to allow the Chicano to survive and persevere with a sense of dignity.”9 In its use of craft, however, Space in Between also fits the parameters of what Mesa-Baines calls domesticana. Attentive to the ways gender roles and expectations shape Chicana life, domesticana is often paradoxical in its simultaneous affirmative and critical stance on the domestic sphere. This sphere and, in particular, its associations with the familial are named explicitly on many of the sculptures on which the words familia and amor appear alongside figural representations of people, old and young, holding hands. Familiar objects in many homes and gardens, the terra-cotta pots that hold the sculptures also bear a relation to the domestic, but they likewise deny the plants’ deep rooting. As such, their relative mobility speaks to the stories of immigration that mark the sculptures’ fabric skin while unsettling the notions of rootedness and particularities of place with which “home” is associated.

The sculptures are lumpy and uneven and bristle with loose threads and heavy, drooping tassels of yarn representing flowers or fruit. The buttons, patches, and seams of the uniforms intermingle with hand-embroidered stick figures holding hands, Mexican flags, and bursting yellow suns, among many other images and words that appear as if drawn in thread. The somatic qualities of the crafting techniques intermingle with those of the fabric whose past life as an article of clothing evokes the presence of bodies whose relation to the makers of these sculptures is one of extreme antagonism. Space in Between orchestrates a renegotiation of the relations of power between immigrants and the US Border Patrol wherein the former haptically rework the iconography of colonial containment that identifies the latter. The distinction Laura Marks makes between optical and haptic visuality is a matter of seeing through and with, rather than at, a difference that disrupts narratives of visual mastery. “When vision is like touch,” she writes, “the objects touch back.”10 The agency and reciprocity of touch that haptical art making offers the colonized subject and their image disrupt hegemonic modes of knowing and colonial world-making projects.

The hypervisibility of the makers’ hands, which in this case are primarily those of Central American and Mexican American immigrants, paired with the use of Indigenous craft techniques, constitute a border aesthetic.11 The use of US Border Patrol uniforms and the regional specificity of the plush cacti cite the material conditions of a border across which many of the participants in Cabrera’s workshops, as well as the artist herself, have crossed. The visibility of processes of production have been read as an index of artistic agency, one not readily available to, nor legible for, Mexican and Mexican Americans in the Euro-ethnic art world. The tactility that characterizes Space in Between, however, also denotes sociocultural processes of identity formation. The crafting of the cacti sculptures, in other words, might be likened to the construction of sexed, raced, and/or gendered identities.12 When viewed through an understanding of border identity as authored primarily by Chicana feminist thinkers, the haptic precarity of Cabrera’s project annunciates the immaterial, political, and ideological conditions of border subjectivity at the same time that it calls forth the terrain, bodies, and institutions that occupy it as space.

The inaugural workshop and exhibition of Space in Between were both hosted at BOX 13 ArtSpace, an artist-run, nonprofit organization housed in a former sewing machine factory and showroom in Houston, Texas. Situating this event in the site of a former factory that would have, no doubt, once employed many Central American and Mexican American workers posits a jarring juxtaposition. In the photographs documenting the activities of the embroidery and sewing workshop, images of women working at Singer sewing machines in close quarters are haunted by the specter of those who once worked at assembly lines in that very building.13 However, as they collectively talk, laugh, and tend to children while they work, the people in Cabrera’s workshops subvert the alienating and dehumanizing conditions that mark the building’s past and the contemporary industrial laborer’s present.

The collaborative structure of Space in Between is a fundamental component of its challenge to capitalist and, therefore, colonial forms of value production. As a mode of making that has long stood in opposition to masculinist Euro-American traditions of art production and sale, collaboration sits uneasily within the hyperindividualism that characterizes the neoliberal capitalism of which the art market is a part. Despite the significant expansion of socially engaged practices since the mid-twentieth century, collaborative art remains largely secondary in value to individually produced work. This is due, in large part, to the fact that their ephemeral structures, which often take the form of performances, workshops, or social events, make them difficult to fit within the rubrics of the commodifiable art “work.” Collaborative, or what we might also describe as participatory, art, as Claire Bishop has noted, is “understood both to emerge from and to produce a more positive and non-hierarchical model.”14 It is also, however, as deeply entangled in processes of value formation as it is with those of representation or politics, despite persisting assumptions that structures of shared authorship and collaboration are inherently more democratic in nature.15 For her part, Cabrera added another element of the egalitarian to her practice when, in 2011, she founded Florezca, a multinational artist’s corporation that allows workshop participants to become shareholders, thus making them eligible to receive a percentage of the profits garnered from the sale of objects created. The specific histories of craft and immigration that Space in Between engage undoubtedly further situate the project as illegible within the capitalist frameworks through which art is valued as such.

At the hands of a Mexican American artist and her largely immigrant participants, moreover, the collaborative is also a mode of making that more closely parallels the processes involved in the production of the types of Indigenous crafts sited in Cabrera’s work, including those used by Otomí craftspeople as well as Purépecha coppersmithing (Craft of Resistance, 2008) and Olmec ceramics (Árbol de la Vida, 2017–19). More than another iteration of the now decades-old art historical tradition of defying single authorship or rupturing passive spectatorship, collaborative art making here is held up against the dehumanizing and alienating characteristics of (im)migrant labor. Furthermore, in her deployment of it, Cabrera’s projects stake a claim in the collective or collaborative as a mode of making that is not rooted in Euro-American art historical narratives of participation, like Bishop’s. Rather, they render visible the Indigenous histories of craft production that have incorporated community engagement and collaboration since long before colonial contact.16

A common argument made in the discourses of art history and craft studies regarding the political potential of craft hinges on the idea that it holds a distinct identity in relation to processes of industrialization and mass production.17 As a response to the seeming decline of the handmade object, craft is frequently called upon to offer the human touch displaced by the automated labor of the factory. For example, in The Invention of Craft (2013), Glenn Adamson argues that craft “emerged as a coherent idea, a defined terrain, only as industry’s opposite number, or ‘other.’” This articulation cemented, Adamson contends, the binary relations of “craft/industry, freedom/alienation, tactic/explicit, hand/machine, tradition/progress” related to the long-contested hierarchical distinction made between craft and art.18 While the hapticality of Cabrera’s sculptures may well suit this narrative, the artist’s use of an Indigenous practice and the fact of the objects having been made primarily by immigrant women mean that to do so would risk reinforcing a colonialist primitivism wherein the “authentic” (read nonwhite) is held up against modern industrial (read white) processes of making.

What Space in Between offers, instead, is an unsettling of the binaries named by Adamson that is distinct from art historical predecessors such as the Arts and Crafts movement, Constructivism, or the Bauhaus, whereby an address of the matrices of race, class, and gender that constitute the identities of folks who make within specific contexts is frequently flattened, if not entirely absent. The bodies that labor at the machines of industry near the Mexico-US border region, like those wielding the tools of craft, are feminized. The intersection of race, class, and gender that typifies the identity of maquiladora workers, as various scholars have argued, positions them as disposable within the economies of global capitalism.19 The historic devaluing of craft broadly, and the near erasure of Indigenous practices within institutions of art more acutely, share patterns of coloniality that, to return to Moraga’s metaphor, weave a narrative rife with the dangling threads of inequity.

This is an issue to which Julia Bryan-Wilson has attended in her writings on contemporary craft, in which she offers various counters to the perhaps romantic notions of craft as somehow unsullied by the mechanisms of capital. The deployment of the term “handiwork” as distinct from the tactile realities of factory labor presupposes a disembodied relation to the latter, the ramifications for which include, among other things, an erasure of the humanity of those who engage in that form of production. In “Eleven Propositions in Response to the Question: ‘What Is Contemporary Craft,’” Bryan-Wilson expounds on the paradoxical realities of craft. It is, she writes, “obsessed with the market, with entrepreneurship, with neoliberal self-branding” as well as a “micro-economy of local making.”20 It is both a reprieve from the onslaught of the digital and a stealthy master of the technological. It is queer, she notes, but also a “machinic, spectacular, macho, hero.”21 Otomí embroidery is itself an example of the economic and ideological complexities of craft existing as both an “authentic” expression of Indigenous identity and a cottage industry with various appropriative appearances in the world of high fashion.22

Recognizing the complexities of craft, Cabrera’s project does not necessarily distinguish factory labor from that which is on display but, rather, highlights the shared relation between the two. The haptic quality of craft becomes coterminous with that of industry, complicated by the relations of touch that already mark the minoritatian body. The generally pejorative associations of monotony and repetition associated with factory labor, moreover, can be said to bear some affinity to the successive stitching and threading associated with many textile arts. This is not to suggest that these forms of labor are the same but instead to provoke consideration of whose labor is made legible and within what contexts.

The Otomí embroidery and sewing methods taught to participants of Space in Between has persisted since precolonial contact, something that is attributed to the relative isolation of the small Hñañhú towns between San Pablito and Tenango de Doria from which it derives. Like many craft traditions of the Americas, Otomí embroidery has historically been taught and practiced intergenerationally by women and girls. The soft succulents created by the workshop participants index this history perhaps most evidently in the colorful embroidered imagery that appears on each of the sculptures. The various species of flora and fauna created, moreover, are indigenous to the American southwest as well as to Los Tenangos, Mexico. The fibers of the agave plant, in particular, were commonly woven into the fabric used by Otomí craftspeople.23 Featured on Mexico’s national flag, cacti hold a variety of social, political, and spiritual meanings that vary within Indigenous groups both past and present. Their presence marks, therefore, not only a particular geographic locale but also a range of cultural signifiers derived from their practical use as sustenance and medicine as well as their role in pre- and post-Columbian Indigenous American belief systems.

The sculptures both literally and figuratively weave together Indigenous Mexican histories with those of contemporary cultural and sociopolitical life. In Fray: Art and Textile Politics (2017), Bryan-Wilson describes the work of Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña (b. 1948) as conceptual craft, providing a reading that resonates with the transcultural hapticality of Cabrera’s. Describing Vicuña’s use of Indigenous South American craft, such as horizontal-loom weaving techniques, as well as her citations of the quipu, the author notes that the artist “perceived indigenous women’s craft as belonging not to a nostalgic or ‘ancient’ past from which modernism can learn aesthetic lessons, but as equal to and continuous with contemporary forms.”24 Similarly, Cabrera’s deployment of craft presents a dialogue between past and present as well as between indigeneity and immigrant identity. Her approach may be better described, however, as an “in-between” rather than an “overlap.” Influenced by notions of the border and border subjectivity offered by Chicana scholars, Space in Between is titled after nepantla, the Nahuatl word for “the space in the middle.” In their “messy,” excessively touched surfaces, Cabrera’s conceptual craft objects don’t merely register the hands of those who worked them, but they also visualize the haptic—the touched—and the indeterminate as the very conditions that define immigrant subjectivity.

Gloria E. Anzaldúa uses the word nepantlism to describe the state of perennial in-between-ness that shapes the consciousness of the mestiza, whose multiplicity of cultural, spiritual, ethnic, and linguistic identities places her “in a state of perpetual transition.”25 There is a long tradition of Chicana feminist thinking that has conceptualized the border as a phenomenology, untethered to an explicit territorialized space. Writers including Anzaldúa and Moraga, as well as Norma Alarcón and Sonia Saldívar-Hull, articulate the border as a subject position formed through the indeterminacy of navigating multiple identities, places, and languages. While many artists have engaged with the decolonial possibilities of liminality, Laura Peréz is careful to note that it is also a “postconquest condition of cultural fragmentation and indeterminacy,” what Anzaldúa called a plague of “psychic restlessness.”26

Space in Between is a deployment of conceptual craft that addresses the particularities of an identity formed through borders both material and immaterial. The workshops create a vital space for the telling and hearing of various migratory stories, while the exhibition of the sculptures that proceeds from them engages a wide audience in modes of haptical visuality that, as Laura Marks notes, encourage a “dynamic subjectivity between looker and object.”27 As such, Cabrera’s work might also be described as what Laura Pérez has named curandera (healer) work. It is a mode of Chicana feminist art making that, as she writes, frequently involves the “invocation and reworking of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican notions of art and art making.”28 Distinct from the recalling of Aztec iconography and myth that typified the Chicano/a Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, curandera work reconfigures various pre-Columbian images and processes of making that map “pathways beyond the alienation and disempowerment of the nepantlism of today’s culture and geographical deterritorializations.”29 Refusing the territorial bifurcations of borders, Cabrera’s projects engage marginalized communities in processes of making that forge collectivity and agency for the historically “touched.”

Cabrera has described the sculptures of Space in Between as “cultural and historical artifacts that value and document the experiences, struggles, and achievements of those who have found their way, often through migration and exceptional sacrifice, to new places.”30 The individuality of each sculpture, a product of the fact that they are both hand sewn and unique in design, insists on a humanizing of immigrants, particularly those who move from south to north. This is amplified by the fact that the sculptures are titled after their mostly female makers, a gesture that not only cedes some authorial agency to the participants but acts as another mode through which the sculptures are anthropomorphized and gendered.

No doubt the difficult conditions in which the real-world counterparts to the desert plants of Space in Between live are also a metaphor for those that immigrants are forced to endure both during their travels across national borders and as noncitizens (whether actual or perceived) within their new communities. In the sculptures, however, the sharp edges and prickling thorns that characterize desert vegetation are rendered in supple and malleable states, unsettling the notions of harshness and danger with which the Mexico-US border region is associated. The needles of the cacti are displaced by those of the seamstress or craftsperson, disarming their prickling armor. The thick skin is made of penetrable fabric, one that is cut, punctured, and sutured by the hands of immigrant women, many of whom have personal experiences with the Mexico-US border and its notoriously unforgiving terrain. The dangers of this climatic and topographical reality are, of course, compounded by the policing of that space by those who bear the uniforms from which the sculptures are made.

In Fray, Bryan-Wilson writes of textiles that the “edges—or borders—are more prone to fraying, as they are subject to more friction.”31 Upon close inspection, one may well notice that the edges of Cabrera’s sculptures remain unselvaged, leaving them vulnerable to the vagaries of touch while also inviting it. Space in Between’s haptics move us closer to the subject and its maker than vision alone, a politics of proximity that feels particularly urgent in this age of the digital. The dangling threads, fraying edges, irregular stitching, and puckering folds evoke the laboring hands of their makers, just as the embroidered images and words communicate a complex and contradictory narrative regarding immigrant identity.

Viewed within the context of the present status of relations between North and Central and South America, one colored by President Trump’s notorious promises to build a wall paired with his administration’s policies of incarcerating or interning those attempting to flee economic or political peril south of the US border, Cabrera’s work seems particularly urgent. Intervening in the dominant narratives of the Mexico-US border that traffic in xenophobic colonial panic, the artist and her collaborators give texture to the lives and experiences of those who traverse the material and ideological terrain of la frontera. The careful embodied and bodying looking that Cabrera’s work engenders offers a productive friction, an exchange of touches that seeks to connect rather than contain.

Angelique Szymanek is assistant professor in the Department of Art and Architecture, Hobart & William Smith Colleges. Her research has appeared in Signs: A Journal of Feminist Scholarship, Women’s Art Journal, and the Journal of Feminist Scholarship. She is the recipient of a US-UK Fulbright Scholar Award (2019–20) and is coeditor of the forthcoming anthology Transnational Perspectives on Feminism and Art, 1965–1985.

- Cherríe Moraga, Native Country of the Heart: A Memoir (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019), 204. ↩

- See Laura Marks, The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Film, Embodiment, and the Senses (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000). ↩

- In Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Wivenhoe, NY: Minor Compositions, 2013), the term “undercommons” describes both shared social conditions of oppression as well as collective responses or resistance to those conditions. ↩

- Rizvana Bradley, “Introduction: Other Sensualities,” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 24, no. 2/3 (2014): 130. ↩

- I borrow the term “haptic tactics” from Cynthia Citlallin Delgado Huitrón. See “Haptic Tactic: Hypertenderness for the {Mexican} State and the Performances of Lia García,” Transgender Studies Quarterly 6, no. 1 (May 2019): 164–79. ↩

- In the context of the industrial manufacture zones near the Mexico-US border, the related issue of feminicide is also of crucial significance. Sexual aggression at the workplace and well beyond it, paired with the thousands of abductions and murders that occur en route to and from the factories, illustrates the pervasive effects of capitalist constructions of human disposability. For an excellent account as it relates to cultural production, see Alicia Gaspar de Alba and Georgina Guzmán, eds., Making a Killing: Femicide, Free Trade, and La Frontera (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010). ↩

- Margarita Cabrera, “Margarita Cabrera,” in By Hand: The Use of Craft in Contemporary Art, ed. Shu Hung and Joseph Magliaro (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007), 32. ↩

- Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, “Rasquachismo: A Chicano Sensibility,” Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation, 1965–1985, ed. Richard Griswold del Castillo, Teresa McKenna, and Yvonne Yarbro-Bejarano (Los Angeles: Frederick S. Wight Art Gallery and CARA National Advisory Committee, 1991), 156. ↩

- Amalia Mesa-Baines, “‘Domesticana’: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquache” (1999), repr. in Chicano and Chicana Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Jennifer Gonzáles et al. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 92. ↩

- Marks, The Skin of the Film, 184. ↩

- There is a rich body of scholarship surrounding the fairly new fields of Border Studies and Border Art that offer a wide range of compelling articulations of border aesthetics, including Ila Nicole Sheren, Portable Borders: Performance Art and Politics on the U.S. Frontera Since 1984 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015), which has been particularly productive in shaping the notions of the border privileged in this essay. ↩

- For an excellent reading of the relationship between handmade processes in art and identity formation, see Jeanne Vaccaro, “Feeling and Fractals: Wooly Ecologies of Transgender Matter,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 21, no. 2/3 (June 2015): 273–93. ↩

- For photo-documentation of the workshop and installation of the exhibition, see Space in Between at BOX 13. ↩

- Claire Bishop, ed., introduction to Participation, Documents of Contemporary Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 12. ↩

- For an overview on the status of collaborative art, see Claire Bishop, “The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents,” Artforum 44, no. 6 (February 2006): 178–83. ↩

- For a history detailing some of these collaborative approaches, see Chloë Sayer and David Lavender, Arts and Crafts of Mexico (San Francisco: Chronicle, 1990). ↩

- This position stems, in large part, from mid-nineteenth-century discourses that shaped critical reception and historicizing of the Arts and Crafts movement, including the writings of John Ruskin and Karl Marx. For a comprehensive historical overview of Euro-American craft discourse, see Glenn Adamson, ed., The Craft Reader (Oxford: Berg, 2010). ↩

- Glenn Adamson, The Invention of Craft (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), xiii. In his extensive writings on the subject, Adamson is clear to identify the ideological work that the modern “invention” of craft subtends, including the imperialist narratives of progress used to justify the colonization of peoples and their labor. ↩

- See, for example, Tanya Maria Golash-Boza, Deported: Immigrant Policing, Disposable Labor and Global Capitalism (New York: New York University Press, 2015); and Melissa Wright, Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Capitalism (New York: Routledge, 2006). ↩

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Eleven Propositions in Response to the Question: ‘What Is Contemporary about Craft,’” Journal of Modern Craft 6, no. 1 (March 2013): 9. ↩

- Ibid., 10. For a rich selection of essays that engage with the issue of the relationship between craft and industry, see Tanya Harrod, ed., Craft, Documents of Contemporary Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018). ↩

- Over the last several years, the clothing company Mango, the designer Carolina Herrera, and the Nestlé corporation have all received formal complaints from the Mexican Human Rights Commission on behalf of representatives of craftspeople from the state of Hidalgo who have attempted to sue said companies for the appropriation of Otomí designs. ↩

- Sayer and Lavender, Arts and Crafts of Mexico, 22. ↩

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art + Textile Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 117. The author briefly discusses Cabrera’s work as well (pp. 264–65), linking the materials and processes used by the artist to “contemporary economic conditions.” ↩

- Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1987), 100. Mestiza is the feminine of mestizo, a term used to describe people of both Indigenous American and Spanish descent. ↩

- Laura Pérez, Chicana Art: The Politics of Spiritual and Aesthetic Altarities (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 21. ↩

- Marks, The Skin of the Film, 164. ↩

- Pérez, Chicana Art, 21–22. ↩

- Ibid., 22. ↩

- Margarita Cabrera: Space In Between, February 10–June 10, 2018, Ruth and Elmer Museum of Art, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY. ↩

- Bryan-Wilson, Fray, 4. ↩