From Art Journal 80, no. 3 (Fall 2021)

Only an Artist Can Tell

Jordana Moore Saggese

Only an artist can tell, and only artists have told since we have heard of man, what it is like for anyone who gets to this planet to survive it. What it is like to die, or to have somebody die; what it is like to be glad.

—James Baldwin, “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity,” 1962

For those who come to it from backgrounds outside Europe (the “ethnics,” “postcolonials,” “minorities,” all those who have ancestry, connections or affiliations “elsewhere”), the arena of mainstream cultural practice in the West, at least in the visual arts, is a doubly predictable space—first, because it is a game space and you have to know the rules of the game, and second, because unlike any other game, such aspirants have a limited chance of success because it is predetermined they should fail.

—Olu Oguibe, “Double Dutch and the Culture Game,” 2001

I was motivated to organize this artist’s project by a series of events in summer 2020. This was a moment of profound social conflict and collective grief in the United States. The murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25 ignited a global movement; previously isolated for months due to the COVID-19 pandemic, people marched together in protest of the legacy of anti-Black violence made so clear in the murders of Ahmaud Arbery (February 23), Breonna Taylor (March 13), Floyd, and Tony McDade (May 27).

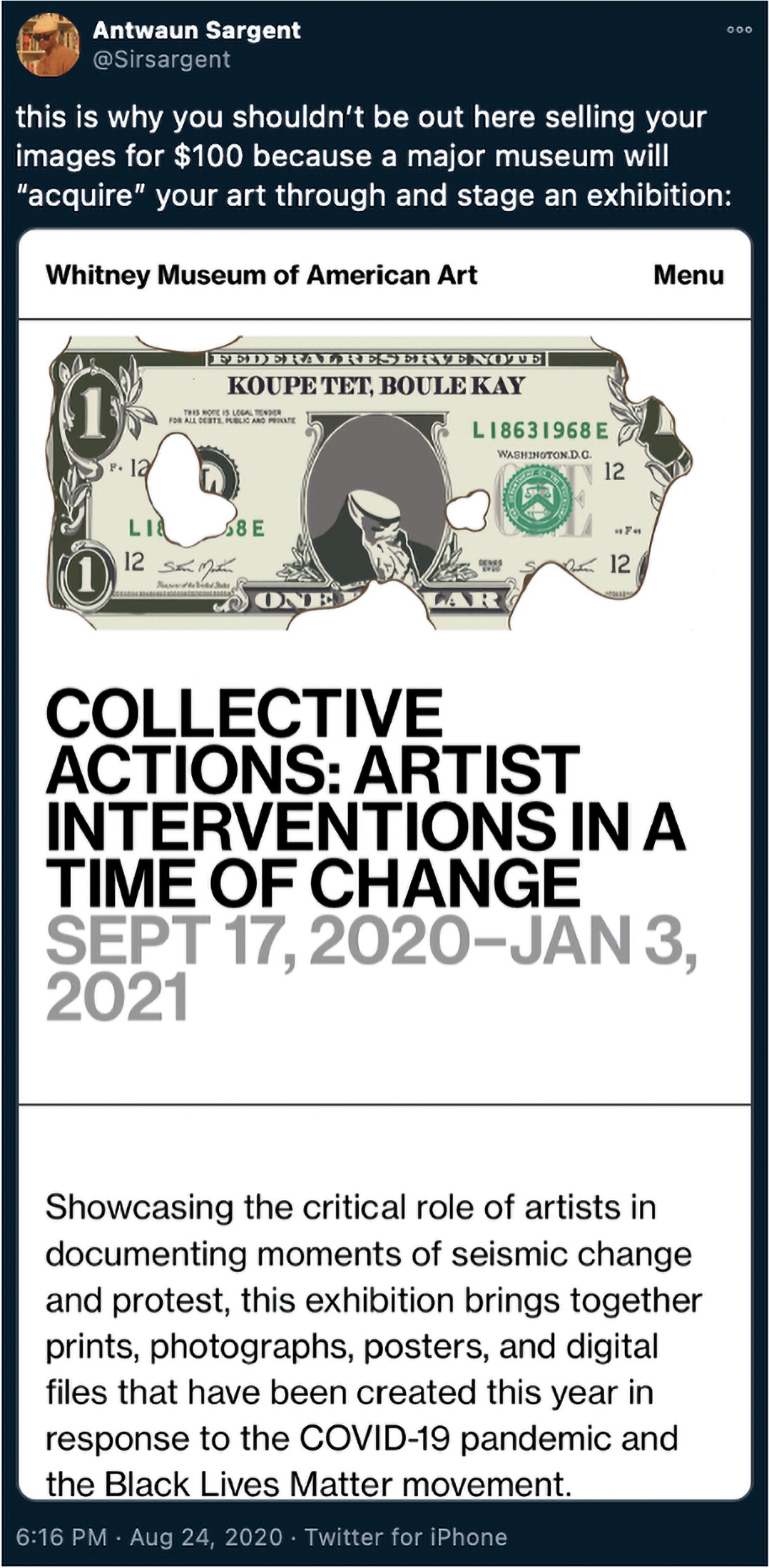

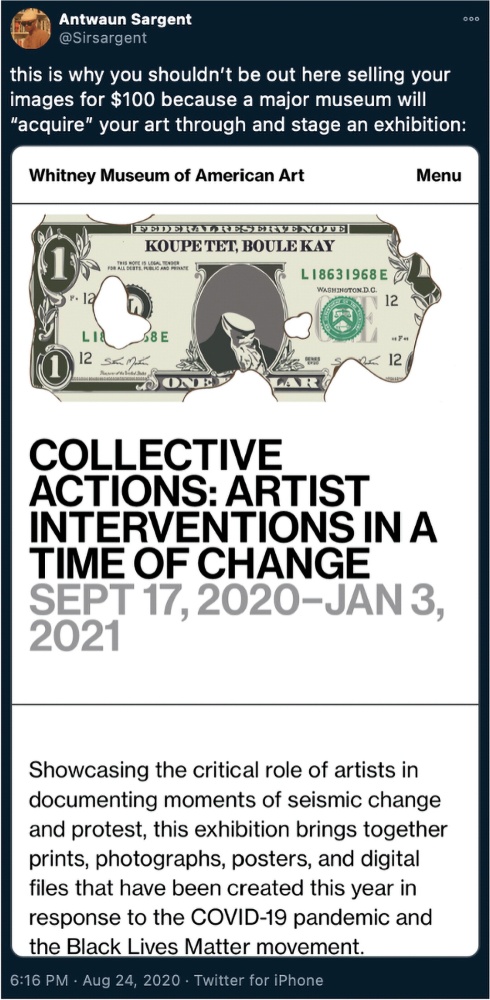

In response to this deep racial unrest, artist collectives were formed. Corporations began to issue statements supporting Black Lives Matter. As I tracked these events—mostly from home and via social media—I noticed that these concerns and initiatives spread to several of the arts organizations in my daily newsfeeds, as well. Large museums started to organize exhibitions that were connected to these social movements (and their heretofore egregious lack of representation in exhibition planning) and to cancel others that were suddenly viewed as troubling in this new “woke” context. Some museums—like the Whitney—did both (see pages 8–13). And artists began (once again) to imagine alternatives to white supremacist violence, to challenge social structures, and to work against hierarchies that mark certain lives as unworthy.

In many cases, artists are being asked to do this work so that the institutions do not have to. The latter are happy to profit off of the public’s sudden interest in what Olu Oguibe has called “tolerable difference”—that is, difference that allows the institution to maintain its superiority, difference that does not challenge its primacy. Tolerable difference, in Oguibe’s words, “by its presence lends credibility to the society’s claims of equity and tolerance and offers proof, if it was needed, that the Empire has room and heart enough for difference.”1 Such an embrace of racial difference by institutions eager to prove their greatness has led to countless special (albeit temporary) curatorial appointments, a bevy of public programs (typically reliant on unpaid or underpaid labor), and even the acquisition of art objects under the auspices of “historical collections.” The projects presented here question the formation of any special initiatives outside of main collections and curatorial programs, and ask which of these collective actions are performative versus transformative.

I want to know: How do we prepare and protect artists (Black artists in particular) who are being called on to correct institutions’ histories of white supremacy? And so I asked Edgar Arceneaux, Michael Ray Charles, alexandre ali reza dorriz, Charles Gaines, Glenn Ligon, Howardena Pindell, and Cauleen Smith for their advice. The generosity of their responses has been overwhelming, and it is my pleasure to offer them here.

- Olu Oguibe, “Double Dutch and the Culture Game” (2000), in The Culture Game (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), 35. [Google Scholar]

Jordana Moore Saggese is the Editor-in-Chief of Art Journal.