July 2021

The following part field report of an outdoor art biennial, part critical analysis of two artworks, part reflection on settler colonialism and land, part self-reckoning, is a quasi review that starts in one place and veers off to another—arriving months after the closure of said biennial (revealing the out-of-sync-ness of my own thought process with the rapid-fire, itinerant culture of the contemporary art world). It is animated by questions that I hope extend its relevance to others caught within the intersecting webs of criticism, art, and the market. Here I use a visit to a particular event to speculate more broadly about speculation itself—the act of looking out across an array, as if from above and outside, and asserting the relative value of things (the task of the critic, by many estimations). How does one embark on such a task while dismantling this kind of positioning along the way—or, maybe and more radically, addressing the unstated power structure at its core? More specific to my piece here, how to think despite yet in relation to various existing structures, whether they be the art-entertainment complex, increasingly metric academic evaluation standards, or—more weightily—settler colonialism? How to adequately approach and amplify practices that reach far beyond the confines of the events that provide them a platform, and, moreover, resist the logic of the event (and of the spectacle) altogether? How to remain open to encounters even when suspicious of their contexts? In the following, I am thinking in the wake of my own decades-long writing about land-based art, especially in the American desert—a form of situated knowledge, to be sure, but one that has been newly unsettled by decolonial and antiracist activism and theory.

***

As an art historian and artist who regularly advocates for critical, politically engaged practices and who denounces those I take to be overly spectacular and/or oriented toward the capital-soaked corners of the art world, I felt somewhat sheepish letting anyone know I was headed to the Coachella Valley of Southern California to check out the third iteration of the biannual outdoor art exhibition Desert X. With a longtime interest and history in this arid neck of the woods,[1] I had been loosely following the event from afar since it started in 2017, encountering it, like many others, through social media and online reviews that featured the most photogenic and talked-about artworks—e.g., Douglas Aitken’s mirrored house from 2017, Mirage, and Sterling Ruby’s monolithic red block, SPECTER, installed two years later. These are pieces that, although seductive looking, have been rightly criticized on multiple grounds, including their fairly abstract treatments of site, which not only emphasize form over context but also, in the process, enact vanishing tricks all too common in the deserts of the American West.[2] Perhaps more obvious is their complicity with the navel-gazing selfie culture of the Instagram era, in which artwork and landscape alike are reduced to flattened backdrops for countless hipster souvenirs, a development that surely has the artist and writer Robert Smithson (1938–1973) rolling over in his grave for its degree of hyperdomestication (even if his own art arguably played some role in its lead-up).

Still, many excellent artists have participated in Desert X since it commenced, and I was ready to experience the thing for myself. I packed my bags, truth be told, most eager to examine not individual artworks, but rather Desert X itself—as a cultural formation that seems especially emblematic of certain contemporary trends, including art and architecture as spectacular events (with the annual Serpentine Pavilions and Burning Man festivals comprising equally relevant reference points); the related rise of art tourism, including to site-specific installations (e.g., extant earthworks from the 1960s and 1970s or Donald Judd’s compound in Marfa, Texas); and the proliferation of biennials and art fairs, in some cases motivated by cities’ or regions’ desires to rebrand themselves and/or to put themselves newly “on the map.” This final factor was certainly at play in the case of the highly controversial Desert X AlUla exhibition in early 2020. This exhibition took place on an ancient oasis in Saudi Arabia through a partnership between Desert X and the Saudi government, the latter hungry to convert the until-then relatively inaccessible area into a premier tourist destination for Saudis and foreigners alike.[3] Not surprisingly, Desert X received sizable flack for the collaboration, which came on the heels of the state-sponsored murder of the dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi, with multiple Desert X board members, including the prominent LA-based artist Ed Ruscha, resigning as a result. It is not unlikely that the most recent, 2021 manifestation of Desert X, back in California, with its heightened attention to social issues (e.g., migration and race) and its inclusion of several artists from underrepresented groups and geographies, marks an attempted image makeover, beyond the more general cultural shift tied to the world-gripping Black Lives Matter uprisings of 2020 and since. Regardless of the reasons, as one friend put it, this is the year that Desert X “got woke.”

I will return to my thoughts on Desert X as a whole at the end, but the majority of this field report—reflecting what tugged at my attention upon arrival, and perhaps risking an overly generous read of the complete affair—will focus on the two pieces created for the 2021 exhibition that I found most trenchant, especially in combination with one another: the Sitka, Alaska-based, Tlingit/Unangax̂ artist Nicholas Galanin’s Never Forget and the Joshua Tree, California-based artist Kim Stringfellow’s Jackrabbit Homestead. In certain respects, these two artworks occupy opposite ends of various poles: one, arguably the loudest and most monumental work of the exhibition, which has already joined the ranks of Aitken’s and Ruby’s in terms of being the most highly visible of its biannual cohort; the other, one of the quietest of the lot. One dwarfs the most massive of billboards, projecting its message across the vast, arid valley spreading at its feet; the other, the scale of a modest tiny home, draws in visitors for close-up inspection and maybe even a precious patch of shade. They roughly mark the westernmost and easternmost points in the array of artworks scattered across the Coachella Valley. In common with each other, and in contrast to most of the other projects on display, they are both sited near heavily used public buildings, the significance of which will become clearer as I say more—namely, the Palm Springs Visitor Center in the case of Never Forget and the Palm Desert Area Chamber of Commerce in the case of Jackrabbit Homestead. Also, each project replicates a specific, historically significant architectural structure. Most important, however, is the crux that motivates me to explore them as a pair: they both address land and property rights, opening onto urgent questions about the past, present, and future human settlement—and, specifically, the settler colonialization—of the region.

Galanin’s Never Forget directly references the ultrarecognizable Hollywood sign, mimicking its form and scale to a tee, yet substituting its towering, white, capitalized letters with “INDIANLAND.” As the artist has repeatedly pointed out, when the original sign was erected in 1923, it read “HOLLYWOODLAND” and served as an advertisement for an upscale, segregated housing development in the hills above the Hollywood district of Los Angeles. (Only later, as the film industry swelled in LA, with elements of it spilling eastward to reach Palm Springs, too, did the sign become a pop-cultural symbol of the city at large.) Beyond being a now-iconic landmark, the Hollywood sign was, in other words, initially built to mark land in a way that exerted racism through space, much like redlining and other processes of territorial exclusion. Galanin invokes and subverts the often crass language of advertising, using it to broadcast a somber and shattering message: long before cities like LA and Palm Springs were urbanized and privatized along stark racial and class-based lines, a profound theft took place. Beneath the endless grids, strips, and watered greens of Southern California—like everywhere in the Americas—the land itself was forcibly converted from Indigenous land to settler land, a dispossession that is not only so broad that it strains full comprehension, but also that persists to this day through continued settler occupation.

In their crucial 2012 essay, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Eve Tuck (Unangax̂) and K. Wayne Yang observe that, within settler colonialism:

Land is what is most valuable, contested, required. This is both because the settlers make Indigenous land their new home and source of capital, and also because the disruption of Indigenous relationships to land represents a profound epistemic, ontological, cosmological violence. This violence is not temporally contained in the arrival of the settler but is reasserted each day of occupation. This is why Patrick Wolfe emphasizes that settler colonialism is a structure and not an event. In the process of settler colonialism, land is remade into property and human relationships to land are restricted to the relationship of the owner to his property.[4]

This passage stresses the spatial and embodied nature of settler colonialism—the way it is executed through the (re)ordering of land and land relations—as well as its unfinishedness, which demands that we look backward and forward in time but also, and perhaps most rigorously, at the present, in order to grasp its reach. Galanin’s earlier work, Shadow on the Land, an Excavation and Bush Burial, made for the 2020 Biennale of Sydney, likewise gets at this unbracketed dimension of the settler-colonial project. In it, earth was excavated into the shape of the shadow cast by a monument of Captain James Cook still standing in Hyde Park in Sydney, Australia (despite growing pressure to dismantle it).[5] The artist has explained that the hole was meant to be dug deep enough to bury Cook’s sculptural likeness as well as the violent legacy it signifies, evoking a future where its presence is in the past while simultaneously underscoring the complicity of archaeology and anthropology with white supremacy.[6] In light of the mass antiracist and anticolonial uprisings of 2020, which frequently involved activists toppling statues similar to that of Cook, we might further interpret Galanin’s artwork to suggest that even in instances where such commemorative markers are ripped from their pedestals, the long shadow of colonialism is still imprinted on the land.

One key element of Never Forget, somewhat overlooked in documentation of the project, is its direct activist dimension—that is, its attempt to intervene concretely into the disrupted land relations at the center of settler colonialism. Parallel to the site-specific installation, and noted on a placard beside it as well as in all official Desert X press about the piece (as required by the artist), there is an online fundraising campaign for the Land Back movement, which works toward putting “Indigenous lands back into Indigenous hands.”[7] During a roundtable discussion between Galanin and several others, including fellow Indigenous artist Gerald Clarke (Cahuilla), Galanin stressed that the artwork is “not the sign” but rather “the history of this land and the conversations that we have and the actions communities are invited to participate in.”[8] In the same exchange, he insisted on the need to supplement spoken land acknowledgements, which have become commonplace in recent years and often pay mere lip service to decolonization, with real, situated action.[9]

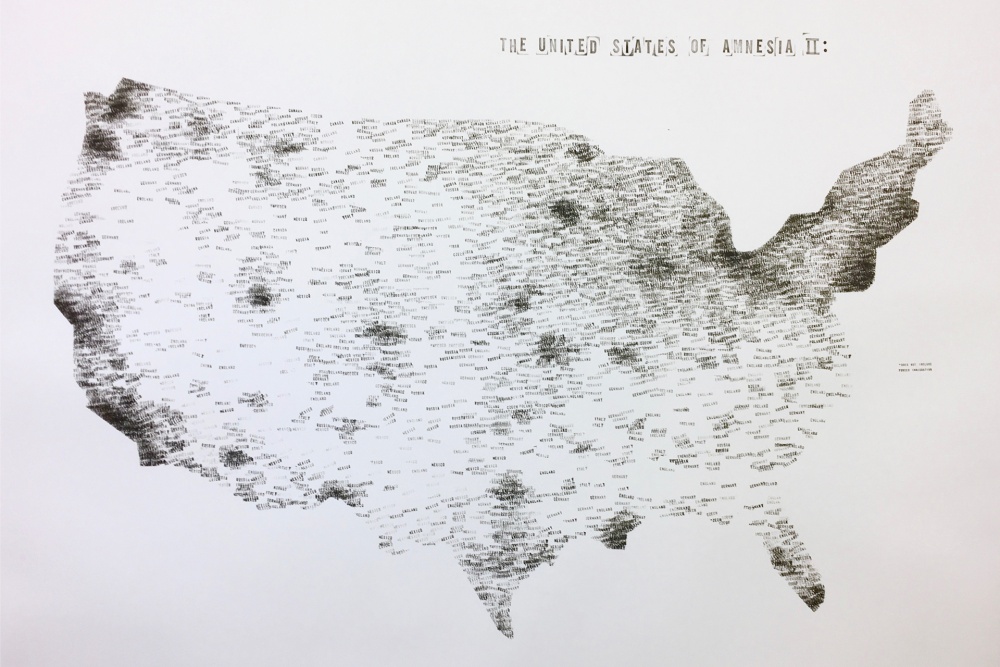

The placement of Never Forget—at the mouth of Chino Canyon along the base of the San Jacinto Mountains, an area of cultural significance to the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians—comes into sharper focus with this emphasis on actual land. Indeed, there was some pushback against the project’s reference to “Indian” land in general, as opposed to the more precise “Cahuilla” ground on which it sits.[10] The sculpture’s adjacency to the Palm Springs Visitor Center and Aerial Tramway just up the road—both fixtures designed and perceived to be gateways to the region and framing particular vistas of it—is clearly also meaningful, especially given the artwork’s core message to remember that which is overlooked or even actively made invisible. The decolonial scholar Macarena Gómez-Barris has noted that the settler-colonial view, like the extractive view to which it is related, is a ubiquitous and “dominant way of seeing world, the land, and even each other,” which “produces amnesia over the violent history and consequences of colonialism.”[11] (The aforementioned tourist infrastructures arguably embody and reproduce such a perspective.) A series of artworks by Clarke on view at the Palm Springs Museum of Art simultaneously with the 2021 iteration of Desert X—part of a brilliant retrospective exhibition that warrants far more attention than I am able to grant here—takes up this issue of settler-colonial erasure, particularly in the case of two pieces: Vanishing 1 (2013), a video in which the artist performs what appears to be a ceremonial ritual, smearing himself with a substance that renders his body transparent smudge by smudge until he ultimately disappears from the wooded natural scenery around him, and The United States of Amnesia II (2017), a large-scale map of the continental United States composed of the rubber-stamped names of countries from which immigrants have arrived (e.g., England, Germany, China, and Mexico), displacing Indigenous inhabitants in the process.[12] The effacement and denial of the land theft at the very foundation of America’s colonial settlement—not to mention that of the ongoing presence and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples—is what Galanin’s Never Forget calls out and seeks to reverse. It demands that we—especially those of us who identify as non-Indigenous—see our own role in the continued settler-colonial project, encapsulated as it is in the American dream of private property so vividly manifested in the Coachella Valley’s shimmering, oasis-like boulevards, gated communities and resorts, and swimming pools. And once we do, they—and we—will never look the same again.

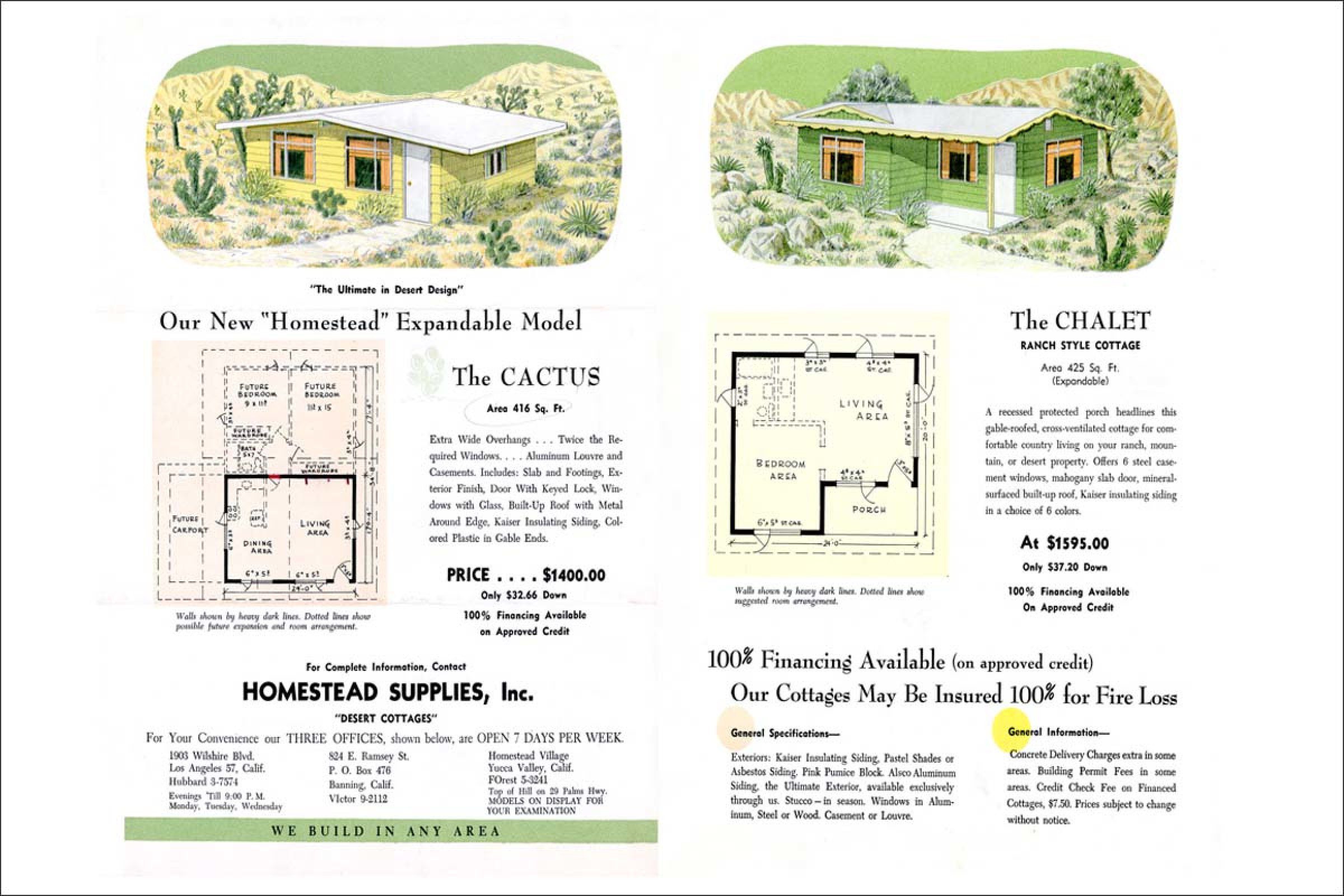

If Galanin’s work opens onto settler colonialism at large, Stringfellow’s Jackrabbit Homestead draws our attention to a distinct historical mechanism that greatly influenced the shape of settlement in the Coachella and surrounding valleys from the mid-twentieth century onward. Specifically, it traces the Small Tract Act of 1938—one in a series of homestead policies instituted by the federal government going back to the nineteenth century—and how it changed the course of development and, by extension, the lay of the land in this arid region.[13] Under the Small Tract Act of 1938, which was especially impactful in the state of California, individuals could apply to lease and eventually own five-acre plots of federal land from the public domain that had been deemed worthless for grazing, mining, and other such uses. One of the “improvements” required to make permanent one’s land claim was the construction of a dwelling with certain minimum building costs and dimensions within three years of arrival. This criterion resulted in the widespread manufacture of look-alike and often prefabricated structures (on similarly regularized gridded parcels)—a peculiar housing-lot prototype known as the “jackrabbit homestead,” which still dots or even dominates parts of the local landscape. More broadly, the Small Tract Act of 1938, together with previous and parallel policies of similar kind, ushered in a sweeping transformation of the US West, refashioning public (formerly Indigenous) land into private property on a grand scale.

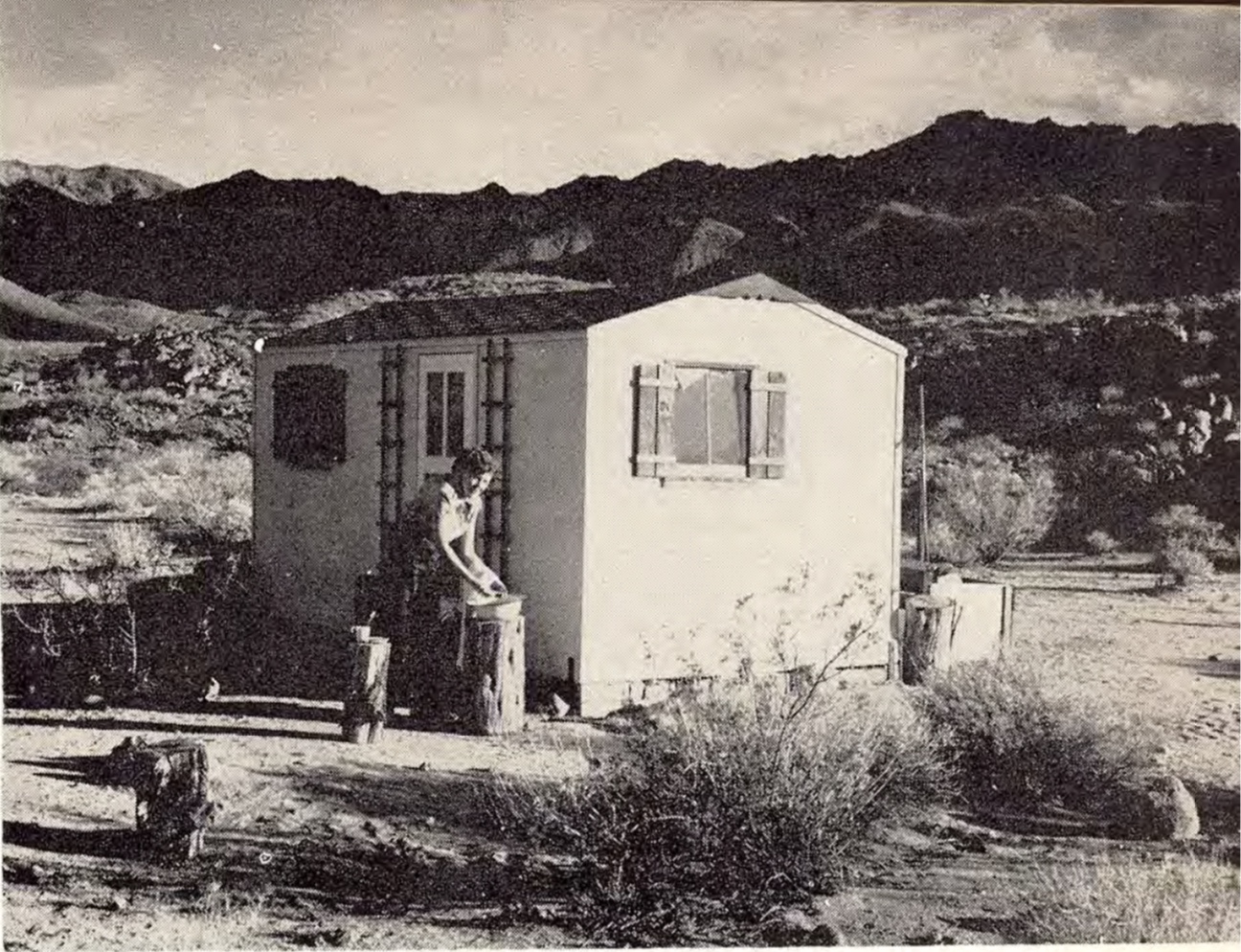

In her project for Desert X—one iteration of Stringfellow’s multiyear, multimedia, and research-intensive project on the phenomenon of jackrabbit homesteading that has variously taken the form of book, sculpture, audio tour, exhibition, and website—the artist narrows in on the story of an individual settler, Catherine Venn.[14] A forty-something office worker and divorcée from Los Angeles who stumbled on a mention of the new land redistribution or “disposal” program in a 1943 newspaper and swiftly submitted her application to the General Land Office in downtown LA, Venn soon thereafter obtained a rocky tract in what would later become known as the Cahuilla Hills of the city of Palm Desert, just southeast of Palm Springs and, like that city, hugging the steep slopes of the San Jacintos. In addition to her notable adventurousness and independence, especially for a single woman in the postwar years, Venn captured Stringfellow’s attention through a six-part series of essays she published in the early 1950s, under the title “Diary of a Jackrabbit Homesteader,” in the local Desert Magazine—itself a major source of boosterism for the Small Tract program.[15]

Venn’s own words indeed serve as the anchor for an enchanting thirty-six-minute audio piece Stringfellow developed in collaboration with composer-musicians Jim White and Claire Campbell, the latter of whom narrates Venn’s letters in the first person. This piece also incorporates field recordings of insects, wind, a passing train, and other ambient sounds to conjure the specific desert context—an audio piece that is embedded within, and emanates from, a life-size sculptural reproduction of the protagonist’s modest cabin.[16] The pristine-looking, shedlike structure itself sits on a tidy patch of ground (more on its exact siting later)—an evocative counterpart to the derelict and/or abandoned real-life jackrabbit homesteads still punctuating the area as well as the luxurious, midcentury modern architecture that has become a main regional attraction, and that one must remember coincided with the jackrabbit homestead’s heyday even if a stark class division existed between the two contemporaneous movements. In approaching the diminutive hut, lured in by the soundtrack wrapping around and animating it (as well as, in my case, the rare pocket of shade it offered on a blistering day), one quickly realizes that to peer through its windows is to discover a wondrous time capsule. The collection of carefully curated objects—e.g., the neatly tucked bed with a handmade quilt; the copy of Edna Brush Perkins’s 1922 novel The White Heart of the Mojave atop the bedside stand; the basket of knitting supplies; the “Home Sweet Home” needlepoint hanging on the wall; the old-school radio and icebox; the typewriter on the Formica kitchen tabletop holding the half-drafted text “Desert Nostalgia”; and the plaid shirt slung over a chair—comprises a vivid tableau and domestic-spatial portrait of Venn, who seems to have just stepped out the door. Akin to a living-history interpretive display or theatrical stage set, this installation represents a piece of historical fiction rooted in rigorous, detail-oriented research. Fleshing out the contours of an otherwise forgotten figure and her vernacular quarters, Stringfellow’s visually and imaginatively riveting piece possesses a kind of affective power rarely found in documentary artistic practices. I am further struck by its intimacy and three-dimensionality as well as the way it engages the scale of the human body, in contrast to a work like Galanin’s, the flatness and colossal nature of which speak to an eye moving across an expanse, not unlikely at the speed of a whizzing car.

For me, the experience of Jackrabbit Homestead was like simultaneously stumbling on a cabinet of curiosities and looking into a mirror. Looking into a mirror in the sense that I am a settler-descended person who, despite my best and increasingly self-reflexive intentions, harbors many a settler-colonial fantasy: I grew up as a 1970s kid addicted to the book and television show, Little House on the Prairie; am a lover of wilderness camping and road trips; recently purchased a 1957 vintage trailer; and have long dreamed of owning land in the desert, my most beloved of places. A pioneering impulse, including the “quintessential American desire to claim territory,” underpins both Venn’s stated eagerness to escape the treadmill of postwar urban life and labor for the apparent freedom offered by the desert and my own, related yearnings.[17] Galanin’s and Stringfellow’s artworks push us to confront the troubling reality that the romance of the reputed frontier so central to the American project—and reperformed in countless seemingly innocuous rituals to this day—is inextricable from Indigenous dispossession and other forms of racial constraint, exclusion, and violence. Stringfellow, herself, has come to similar conclusions over the course of her research for the project:

I have come to understand jackrabbit homesteading as an “entitlement” for a certain racial and/or ethnic group of American citizens notwithstanding their class or economic status. This entitlement was driven by the outdated but persistent settler narrative spoon-fed en masse via popular culture—in the form of the romanticized Hollywood Western that was entering its height of popularity when the program began. This exclusionary and violent narrative must be considered while reflecting on the Small Tract homesteading experience as it informs how participants either saw or projected their collective identities onto the landscape.[18]

The artist’s choice to locate her installation next to the Palm Desert Area Chamber of Commerce and its ample parking lot, just off Highway 111 in an area now dense with big-box retailers, goes a long way toward deromanticizing the setting, as Desert X artistic director and curator Neville Wakefield astutely pointed out during an online listening party inaugurating the piece.[19] More specifically, its adjacency to a building devoted to regional business growth suggests that we acknowledge the role of capitalist development, a sibling of settler colonialism, in configuring local geographies—something which, when applied to the present, begs serious reflection about a range of all-too-obvious yet complex and interrelated trends of the day, from the explosion of private vacation rentals to the encroachment of shiny Airstreams and other elements of “van life” to crowd-drawing cultural events like Desert X itself.[20]

Galanin’s Never Forget and Stringfellow’s Jackrabbit Homestead help to critically situate and hone our views of the here and now and the then and there of the Coachella Valley. More precisely and significantly, these artworks foreground our embeddedness and implicatedness in the structure of settler colonialism—a structure that is far-reaching and yet plays out and is produced in highly specific ways (geographical, political, financial, performative, and more). In this respect, the works depart from a majority of past and simultaneous Desert X projects, which have erred on the side of spectacular form, phenomenological interest, and/or vague references to the desert.[21] They likewise contrast with most iconic works of Land art from the 1960s and 1970s, which have involved a degree of willful forgetting, or blindness to the human history of the land, in order to facilitate novel, artist-framed experiences of space—experiences that indeed depend on certain erasures.[22] Desert X is clearly indebted to and extends the legacy of Land art, sometimes repeating this same problematic tendency, even though Wakefield is alert to Land art’s common failure to “examine the history of the land on which it took place.”[23] And, ultimately, it may be that Desert X as a whole—by its very nature, which rests on a distinctly twenty-first-century glamorization of art and the desert alike—has built-in limits to its critical purchase. Never Forget and Jackrabbit Homestead, however, possess an abiding power. And, they do so because they mark the land in order to show how it has, itself, been marked and continues to be marked by forces that are ongoing and anything but inevitable.

Emily Eliza Scott is an interdisciplinary scholar, artist, and former park ranger who holds a joint professorship in art history and environmental studies at the University of Oregon. The author of numerous essays on contemporary art and design practices that engage pressing (political) ecological issues and coeditor of The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change (2021) and Critical Landscapes: Art, Space, Politics (2015), she is currently writing a book on art that tracks environmental violence as it is writ into land, air, and water.

[1] My connection to the Mojave Desert of Southern California dates back to my years as a graduate student at UCLA in the early 2000s, when I headed east of the city regularly to hike and camp. I also attended several of the first High Desert Test Sites gatherings initiated by the artist Andrea Zittel, performing there once with the Los Angeles Urban Rangers collective I cofounded in 2004. Much of my research in graduate school centered on the desert and ways that it has been taken up as a testing ground by artists, architects, militaries, and speculators alike. Before entering academia, I worked as a National Park Service ranger in Arches and Canyonlands, two desert parks in southeast Utah, for nearly a decade.

[2] Another essay of mine elaborates on the theme of the desert as a site of erasure: Emily Eliza Scott, “The Desert in Fine Grain,” in The Invention of the American Desert, ed. Lyle Massey and James Nisbet (Oakland: University of California Press, 2021), 145–64.

[3] Vivan Yee, “Art Rises in the Saudi Desert, Shadowed by Politics,” New York Times, February 11, 2020: Art, Land, and the Politics of Environment.

[4] Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 5. The Wolfe reference in this passage is: “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research, 8 (4), 387–409.

[5] The statue of Captain Cook in Hyde Park is still standing, but it has been vandalized multiple times, including in 2017 and again in June 2020 during the Black Lives Matter protests that swept the globe after the murder of George Floyd and that took place in Sydney just days after the closing of the 22nd Biennale on June 8, 2020. For more on Galanin’s work and the controversy surrounding its primary subject, see Trupti Rami, “It’s Funeral Time for Colonial Monuments,” Vulture, June 19, 2020, https://www.vulture.com/2020/06/nicholas-galanin-shadow-on-the-land.html.

[6] There are several short interviews with Galanin about his Sydney project, in which he speaks about white supremacy and colonialism. See, for example, the April 29, 2020, interview available on Facebook (https://fb.watch/7GkGxR6le-/ ) and the December 11, 2020, interview conducted as part of PBS’s Craft in America series (https://www.pbs.org/video/nicholas-galanin-shadow-land-and-excavation-and-qblj8m/).

[7] Galanin, who frequently identifies himself by his Indigenous name, Yéil Ya-Tseen, organized a Gofundme page for the fundraising campaign; see https://www.gofundme.com/f/landback. The manifesto of the LANDBACK campaign organized by the NDN collective can be accessed online at https://landback.org/manifesto/.

[8] Galanin made this remark during “This Land: Making Never Forget,” a panel discussion hosted by Desert X in partnership with the Native American Land Conservancy on May 14, 2021. A full recording of the discussion, which included Galanin, Clarke, Stephen Nichols, founder of the Chino Cienega Foundation, and Sean Milanovich (Cahuilla) of the Native American Land Conservancy, can be accessed online at https://desertx.org/learn/programs/this-land-making-never-forget

[9] Ibid.

[10] In the aforementioned roundtable discussion, an objection to the term “Indian” arises during the Q&A, in response to which Galanin appears exasperated; Clarke jumps in to defend the artist’s choice to use a word understandable to a broader audience. A lively conversation ensues about the connotations of “Indian” as a “blanket term” that was used by the colonizers, but that has often been adopted toward self-determining ends. A more troubling controversy erupted after the unveiling of Galanin’s artwork when the LA-based, Tongva/Scottish artist Weshoyot Alvitre alleged plagiarism of her 2019 “intentionally digital” artwork riffing on the Hollywood sign with the word “TONGVALAND,” in recognition of the ancestral homelands comprising the present-day LA Basin. For more on these events, see https://www.californiadesertart.com/weshoyot-alvitre-responds-to-indianland-installation/. I wish to acknowledge my friend and activist-artist-scholar Nicholas Brown, for drawing my attention to this second controversy.

[11] This quote is pulled from a roundtable discussion between Jaskiran Dhillon, Tami Navarro, and Gómez-Barris titled “Climate Change, Decolonization, and Ways of Seeing.” The discussion was recorded at Verso Books in Brooklyn, New York, on September 13, 2018; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Txtoe06ypY4. Gómez-Barris’s book The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018) more broadly theorizes her notion of the “extractive view” and provides in-depth analyses of the work of several Latin American artist-activists.

[12] For more on the exhibition, see David Evans Frantz and Christine Giles, eds., Gerald Clarke: Falling Rock, exh. cat. (Munich: Hirmer Verlag and Palm Springs Art Museum, 2020).

[13] The first and best known of these policies was the Homestead Act of 1862, which opened the possibility for private owners to claim 160-acre plots of formerly public land, provided that they settle and make them “productive” via farming, mining, grazing, or the like. As illuminated in Stringfellow’s extensive research on the subject, the 1938 Small Tract Act, initially conceived to compensate war veterans, appealed, by contrast, to mostly working-class individuals seeking land for domestic and/or recreational purposes. Importantly, its widest application was in areas deemed by the federal government to be devoid of resources or otherwise worthless for economic development.

[14] To learn more about Stringfellow’s wider work on jackrabbit homesteading, see the main project website at https://jackrabbithomestead.com, which includes a “primer” on the subject; access to a self-guided audio tour (by car) of jackrabbit homesteads in Wonder Valley, California; documentation of previous exhibitions; and a link to order her 2021 book, Jackrabbit Homestead: Tracing the Small Tract Act in the Southern California Landscape, 1938–2008 (Joshua Tree, CA: Kim Stringfellow Press), which is full of information as well as photographs by the artist. While beyond the scope of my discussion here, Stringfellow’s practice is a fascinating example of sustained, site-specific, and interdisciplinary artistic research. For decades now, she has operated as a cultural geographer, “desert anthropologist” (her term), and environmental historian of sorts, with a focus on the landscapes of California, especially the deserts of Southern California. Other notable projects include her 2005 book, Greetings from the Salton Sea: Folly and Intervention in the Southern California Landscape, 1905–2005 (Santa Fe, NM: Center for American Places); and a 2006–7 critical audio tour of the I-5 corridor, Invisible-5, made in collaboration with San Francisco-based artist Amy Balkin, sound producer Tim Halbur, and several environmental justice advocacy groups (available online at http://www.invisible5.org). On the latter project, see my essay “Field Effects: Invisible-5’s Illumination of Peripheral Geographies,” Art Journal 69, no. 4 (Winter 2010): 38–47.

[15] Conversation between the author and artist, May 14, 2021.

[16] The soundtrack can be accessed via Soundcloud at https://soundcloud.com/kstringfellow/jackrabbit-homestead-desert-x-2021?utm_source=clipboard&utm_campaign=wtshare&utm_medium=widget&utm_content=https%253A%252F%252Fsoundcloud.com%252Fkstringfellow%252Fjackrabbit-homestead-desert-x-2021; it is also available on Stringfellow’s website devoted to her ongoing work on jackrabbit homesteads, including its iteration for Desert X: https://jackrabbithomestead.com/jackrabbit-homestead-desert-x-2021/

[17] See Stringfellow’s overview essay on “Jackrabbit Homestead at Desert X 2021”: https://jackrabbithomestead.com/jackrabbit-homestead-desert-x-2021/.

[18] Ibid.

[19] A full recording of the panel discussion and “listening party” for Jackrabbit Homestead, which was hosted by Desert X on May 1, 2021, and which included artist Stringfellow, composers/musicians White and Campbell, and Desert X artistic director Wakefield, can be found here: https://desertx.org/learn/programs/listening-party-jackrabbit-homestead-with-kim-stringfellow-jim-white-and-claire-campbell.

[20] The 2020 film Nomadland, directed by Chloé Zhao (Los Angeles, CA: Searchlight Pictures), is worth mentioning here for its arresting portrait of “van life” and the razor-thin edge between itineracy and precarity that often comes along with it. The film highlights the increasingly blurry line between nomadism and houselessness in present-day America, particularly since the 2008 financial crisis (not to mention the arrival of COVID-19, which occurred after the completion of the film and has immeasurably exacerbated the issue of houselessness in the United States)—especially in the American West. It is also notable that “more than half of the country’s unsheltered homeless population resides in California,” not only in its cities but also in its rural and desert reaches, and partly as a result of the kinds of racist zoning and housing policies mentioned all too briefly in my own discussion. See Ned Resnikoff, “It’s Hard to Have Faith in a State That Can’t Even House Its People,” New York Times, July 26, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/26/opinion/homelessness-california.html.

[21] Eduardo Sarabia’s The Passenger—a visually and phenomenologically alluring triangular maze structure composed of woven palm-fiber mats, with an agora-like center offering views of both its interior and the scrubby landscape beyond its walls—was a standout at the 2021 exhibition in this connection.

[22] My 2018 essay, “Decentering Land Art from the Borderlands,” which also appeared in Art Journal Open and in some ways works as a companion piece to this one, examines the settler-colonial and patriarchal dimensions of iconic Land art from the 1960s and 1970s in more depth.

[23] From the panel discussion and “listening party” for Jackrabbit Homestead, see note 19.