From Art Journal 81, no. 1 (Spring 2022)

Will Wilson

In 2012 I began the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX), centering Indigenous, ethics-based aesthetics through a critical dialogue around the photographic exchange we understand as portraiture. Ultimately, I want the subjects of my photographs to participate in the reinscription of their customs and values, leading to a more equal distribution of power and influence in the cultural conversation. In 2019 I commissioned Allison Johnson, professor of film at Santa Fe Community College, and Thomas Vause of Digital Ant Media to develop the Talking Tintype app in order to give voice o my photographic subjects by bridging nineteenth- and twenty-first-century technologies. Also in 2019, Adam W. McKinney, professor of dance at Texas Christian University, invited me to collaborate on the Fred Rouse Memorial Project.

Adam W. McKinney

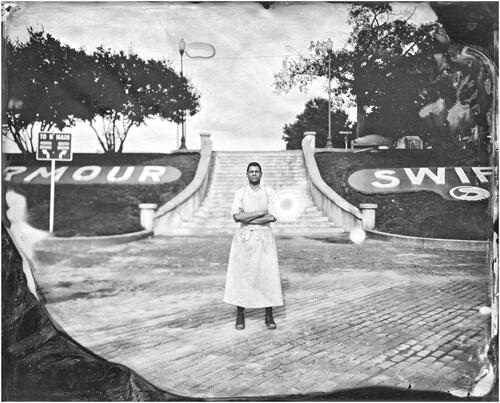

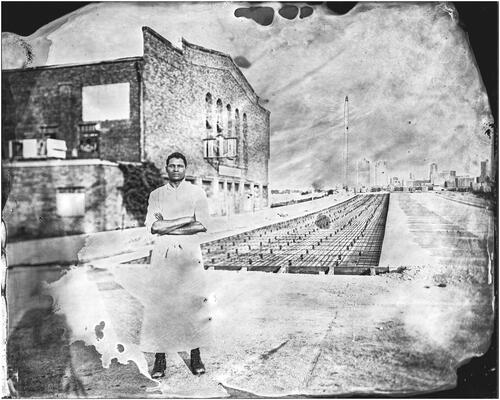

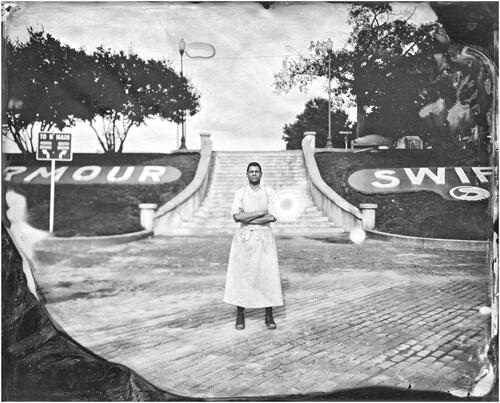

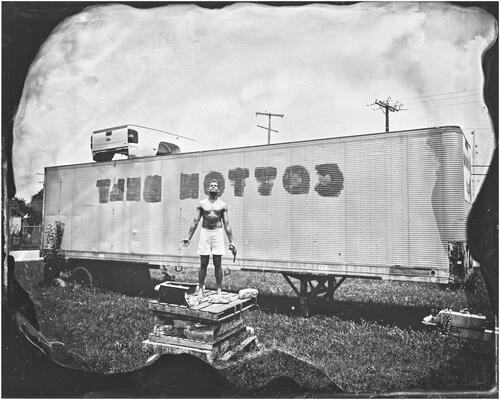

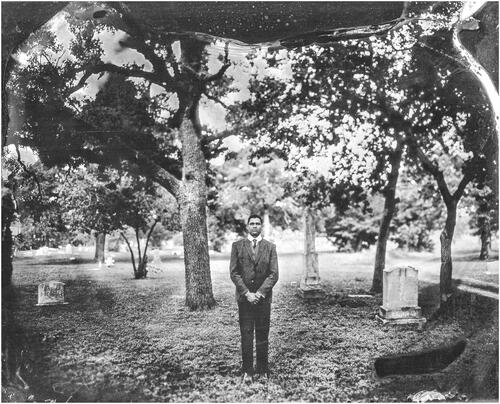

When I arrived in Fort Worth, Texas, I learned of the 1921 racial-terror lynching of Mr. Fred Rouse. As I began to delve deeper into this undertold history, I asked individuals, organizations, and institutions what they knew about Mr. Fred Rouse. I soon realized that most had little to no information. Therein began my journey to remember Mr. Fred Rouse. With Will and Daniel Banks, I traveled to each of the five Fort Worth locations associated with the racial-terror lynching. Through choreography and photography, I used my body to remember Mr. Rouse by transporting my body across space and time, linking the anti-Black racial terror violence enacted upon Mr. Rouse to all the ways my own body has been, and is, targeted by racism. Will’s tintypes became the inspiration for DNAWORKS’s Fort Worth Lynching Tour: Honoring the Memory of Mr. Fred Rouse (FWLT) bike and car tours and the FWLT augmented reality app.

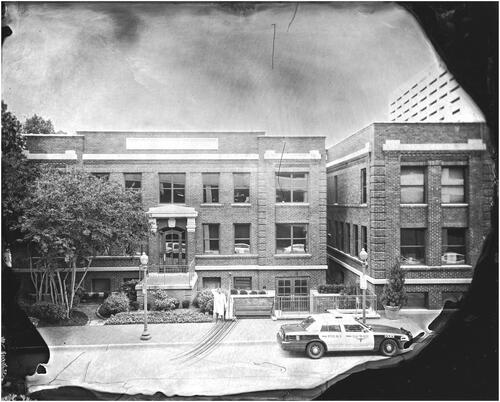

In the early 1920s, Fort Worth had one of the largest Ku Klux Klan memberships in the United States. In 1921 KKK Klavern No. 101 began construction on an auditorium at 1012 N. Main Street. After a mysterious fire, it was rebuilt in 1925. The Klan used the building for meetings, rallies, initiations, and performances including minstrel shows. In 1925 Harry Houdini, one of the guest performers, asked, “Can the dead speak to the living?”

In 1931 KKK membership dwindled and the Klan sold the building. It was subsequently used as a department store warehouse and later as a dance-marathon auditorium, a wrestling and boxing arena, and a pecan-shelling factory.

In 2019 DNAWORKS coconvened Transform 1012 N. Main Street (T1012), a nonprofit organization, to acquire the building. In early 2022, T1012 announced its purchase and future transformation into the Fred Rouse Center and Museum for Arts and Community Healing.

Mr. Fred Rouse was a nonunion butcher for Swift & Co. Meatpacking Plant in the Niles City Stockyards (now in Fort Worth’s Northside neighborhood). On Tuesday, December 6, 1921, at 4:30 p.m., when leaving work, Mr. Rouse was threatened and accosted by strikers and agitators. Mr. Rouse was shoved, then stabbed. As he defended himself from the crowd, a struggle ensued and Mr. Rouse was accused of shooting two white men. A mob then began to beat and bludgeon Mr. Rouse with a streetcar guardrail. With his skull fractured in two places, internal injuries, and several stab wounds, Mr. Rouse was left for dead in the middle of Exchange Avenue. Niles City police officers asked the mob to relinquish Mr. Rouse to law enforcement. They placed Mr. Rouse’s body in the back of a police car. On the way to the mortuary, discovering that he was still alive, they drove him south to City & County Hospital.

After Mr. Fred Rouse was attacked and left for dead in the Niles City Stockyards, he was taken to the basement of the Negro Ward of City & County Hospital. On December 11, 1921, at approximately 11:00 p.m., a mob of white men entered the hospital while Mr. Rouse was recovering from the injuries he incurred. The men threatened the hospital staff, forced their way into the Negro Ward, kidnapped Mr. Rouse in his hospital gown, and drove north on Samuels Avenue to the “Death Tree.”

The white mob drove Mr. Fred Rouse from City & County Hospital to the southeast corner of Northeast 12th Street. There they hanged Mr. Fred Rouse on a hackberry tree known as the “Death Tree.” According to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, “His body was riddled with bullets.” Word traveled quickly. For the next hour, a parade of cars drove up and down Samuels Avenue to witness the hanging. A bloody gun was discovered beneath Mr. Rouse’s feet.

In January 2021, and in partnership with the Rainwater Charitable Foundation, Tarrant County Coalition for Peace and Justice (TCCPJ) purchased the site of the racial-terror lynching of Mr. Fred Rouse. On December 11, 2021, TCCPJ held a groundbreaking for the Mr. Fred Rouse Memorial including the installation of an Equal Justice Initiative historical marker. With the groundbreaking, TCCPJ transformed this site of trauma into one of reconciliation and memorial activism.

Mr. Fred Rouse was buried in New Trinity Cemetery, Haltom City, Texas, on Monday, December 12, 1921. Little is known about his burial, or even if he had a ceremony. Mr. Rouse’s father, brother, and son are also buried in New Trinity Cemetery. No headstone for any of the Rouse family members has been located.

All images: Adam W. McKinney and Will Wilson, SCAB: Honoring the Memory of Mr. Fred Rouse, 2019–ongoing, archival pigment print with app-activated augmented reality, from scans of the original 8 x 10 in. tintypes, variable (artwork © Will Wilson Art & Photo, LLC, and DNAWORKS, LLC)

Talking Tintypes app

Talking Tintypes is an augmented reality (AR) photographic experience created by Dine photographer, Will Wilson.

To use the app, scan the QR code at left, install the app, and scan the photographs. To activate the augmented reality (AR) content of the photographs in this article, scan them with the Talking Tintype app. You may also access limited content by visiting the artist’s website and selecting the Talking Tintypes collection.

Will Wilson’s art projects center around the continuity and flow of Indigenous cultural practice. He is a Diné photographer and transcustomary artist. Wilson studied photography, sculpture, and art history at the University of New Mexico (MFA, photography, 2002) and Oberlin College. In 2010 Wilson received the Joan Mitchell Foundation Award for Sculpture, in 2016 the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant for Photography, and in 2017 the New Mexico Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts. Wilson is a committed educator who has taught at the Institute of American Indian Arts, Oberlin College, and the University of Arizona. Wilson is program head of photography at Santa Fe Community College.

Adam W. McKinney is a dancer, choreographer, activist, educator, and installation artist. He has danced professionally with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Alonzo King LINES Ballet, and Milwaukee Ballet Company, among others. His research interests include dance and performance studies, trauma studies, community, trauma, healing, and technology. He is the coartistic director of DNAWORKS, an arts and service organization committed to healing through the arts and dialogue. McKinney holds a BFA in dance performance from Butler University and an MFA in dance studies with concentrations in race and trauma theories from the Gallatin School at New York University. McKinney is an assistant professor of dance at Texas Christian University.