From Art Journal 81, no. 2 (Summer 2022)

Portraits are performances, from the studio to the selfie. The evasiveness of the photographed subject—their knowing permutations of identity before the lens—is a given, but what if this now-routine habit could be restored to the strangeness of its origins? What if the portrait was no mere document but a portal into another world? Such apertures are exactly what the UK-based artist Robert Taylor happened upon in 1987 when he met a young, Nigerian-born, American-educated photographer named Rotimi Fani-Kayode (1955–1989) at a gay men’s social group in London.1 He soon commissioned a portrait for himself. Their encounter typified the forms of avant-garde experimentation in London in the late 1980s, and also belied a decade that New York-centric art histories have long shorthanded as an era of slick postmodernist production, emphasizing deft symbolic appropriations and anachronistic pastiche. Certainly, the suffocating orthodoxy of modernist formalism was then on the retreat in many studios and galleries around the world, but the so-called postness of the moment poorly describes the persistence of long-standing artistic strategies only recently made legible: the metaphysical, the affective, and the surreal.2

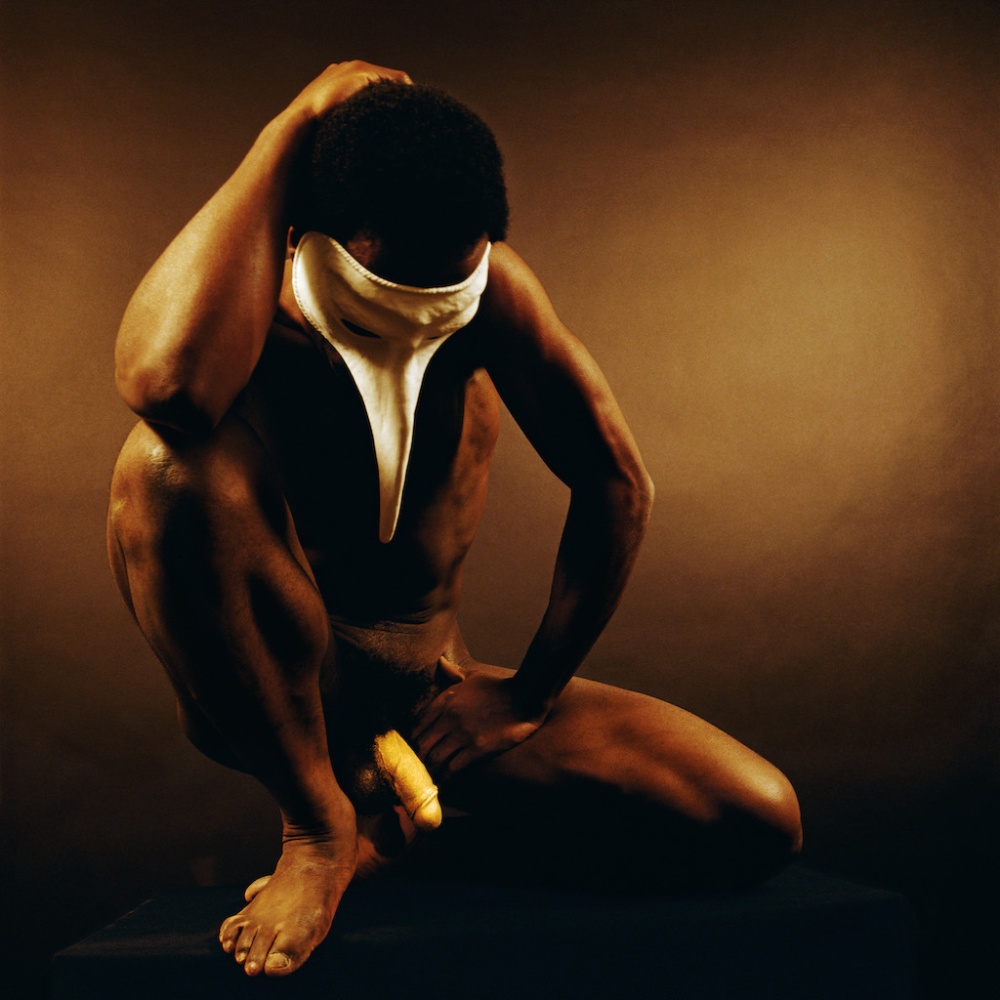

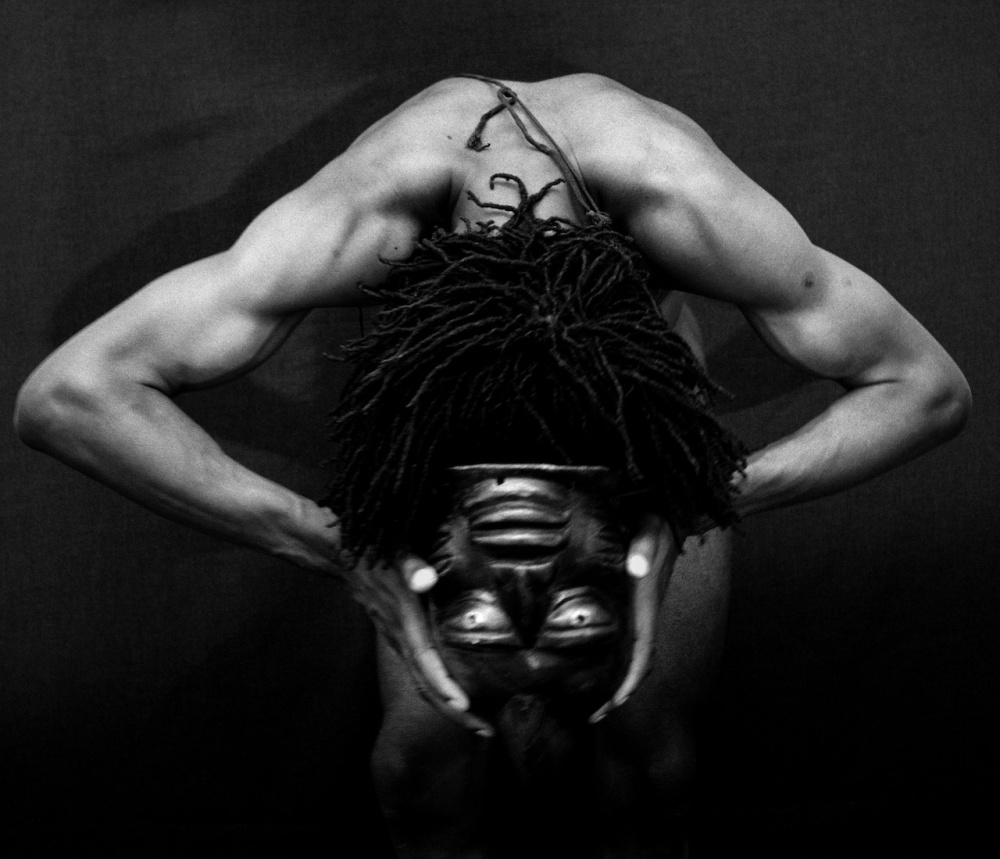

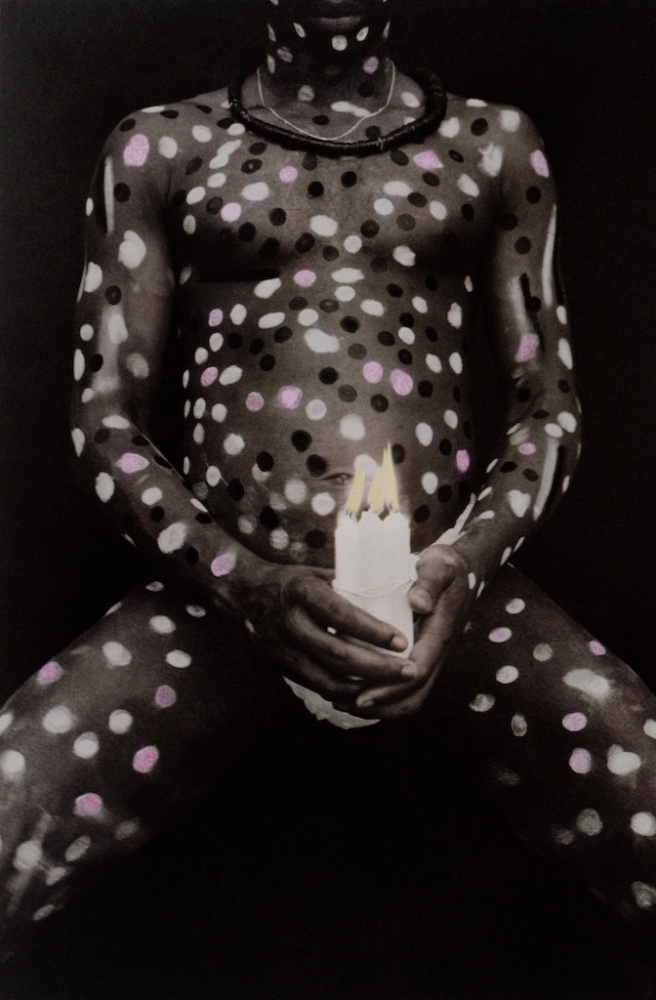

Taylor recalls that Fani-Kayode was striking, in both his gravity and his beauty, yet came across as gentle, unassuming.3 Apparently Taylor frequented the artist’s Railton Road studio in Brixton and eventually posed for him, nude save for a beaked Venetian carnival mask and a conspicuously painted member. This Golden Phallus series, each image lushly tenebristic, printed in rich chromogenic color, crystallizes Fani-Kayode’s studio work with a coterie of Black models (and with partner Alex Hirst) in the seasons leading up to the former’s untimely death in December of 1989. Bare bodies and multiple resonant props were mainstays of his practice, but his last several series took on a plainly somber tone, depicting scenes of spiritual communion or rituals of death and transfiguration. Taylor notes that in retrospect he was prepared for those sessions, carefully choreographed for the emergence of something beyond the materiality of the picture itself. Fani-Kayode likened it to an aspect of Yoruban religion, what he called a “technique of ecstasy,” likely an allusion to the shearing of one’s identity through the invocation of sacred knowledge in the form of the orisha—deities that mediate between individuals and the spirit world. According to Taylor, “typical portraiture was the furthest thing from any of our minds as far as I was concerned. . . . I trusted him and would have done pretty much anything he asked, pretty secure in the knowledge that it would be very likely fascinating, challenging, and beautiful. . . . By the time it came to actually stripping off the body painting and the ‘gold penis performance’ with the paint, the three had entered a strange little world that was only properly apparent when the lights were cut and ‘normal’ life resumed.”4

It is tempting to view Fani-Kayode’s photography as idiosyncratic. As I argued in a recent monograph, his work operated at the intersection of art and activism, his pictures drawing together an array of technical and performative modes.5 Viewed primarily through circulating artists’ books, these images documented a confluence of Victorian pictorialism, Dada and punk-infused montage, Yoruban divination, and the gelede veneration of women, gay print culture, Romantic literature, Greek mythology, and contemporary poetry. There are, however, at least two ways in which such photographs resuscitated methods long used by artists to navigate the psychic terrain central of, but until the late 1970s elided by, the rhetorics of twentieth-century modernism—that is, Surrealism.6 Fani-Kayode worked between 1983 and 1989, when European Surrealist photography was brought into focus by several influential exhibitions, and gothic motifs infused sonic and visual culture anew. At the same time, he consistently foregrounded deeper entanglements between those European artists and the Black Atlantic world, elaborating too the Surrealisms generated across the African diaspora.7

In writing my book, however, a third Surrealist connection emerged—between Fani-Kayode and Eikoh Hosoe (b. 1933), a noted Japanese photographer who made his reputation during the 1960s but remained active in the ensuing decades.8 I was unable, at that time, to pursue this connection to the extent that I had hoped. My aim in the pages ahead is both to elaborate this work and to explore the far- reaching implications therein for emerging histories of modernism and photography. For his part, Hosoe is perhaps best known for several artist’s books that use avant-garde techniques to explore sexuality and power (Man and Woman, 1960), the fallout of the Second World War (Return to Hiroshima, 1970), and a 1961 collaboration with novelist Mishima Yukio entitled Barakei. The latter bears striking affinities with the scene outlined by Taylor, of a portrait session that assumed ecstatic dimensions, the resulting photographs mediating libidinal, even spiritual terrain. While Fani-Kayode and Hosoe worked at a great geographic remove, both mobilized Surrealist photographic strategies to mediate ongoing forms of collective trauma, and did so by positing a deeply intimate application of the medium.

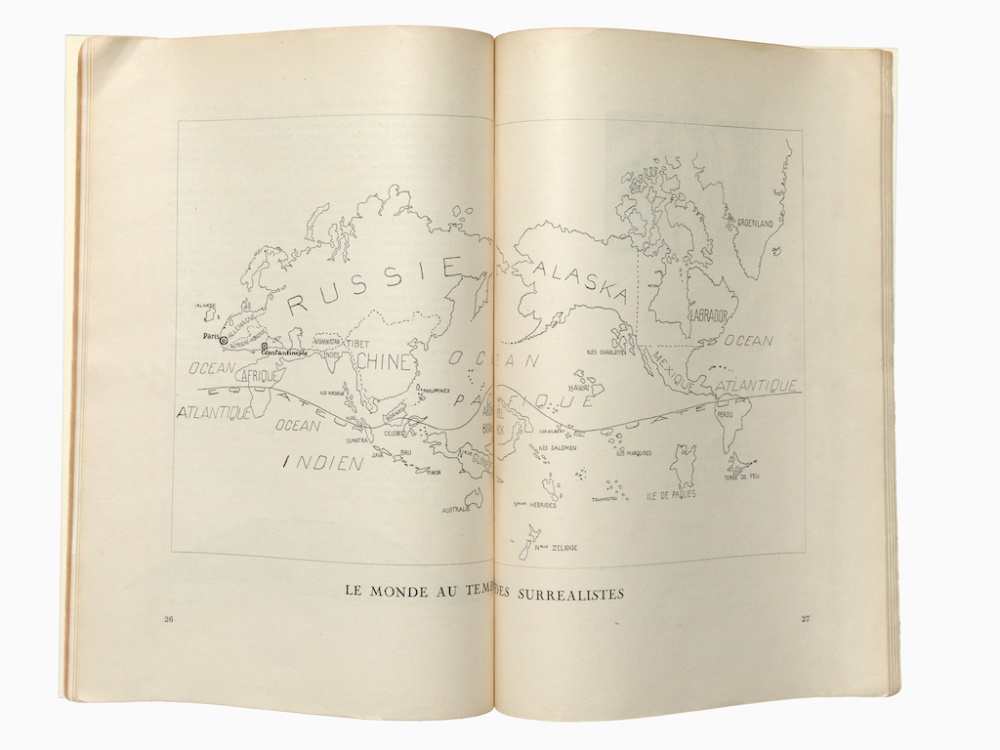

Both artists also engaged with specters of death that prefigured those crucial years leading up to 1989: the cultural alienation forged by occupation and its aftermath, and the trauma of cells that betray their bodies in the form of radiation poisoning and HIV. Beyond the many procedural and thematic similarities in their oeuvres, Fani-Kayode and Hosoe, when considered together, bring into view new cultural bases for Surrealist practice and patterns of influence that bypass or complicate more Eurocentric histories of twentieth-century avant-gardes. While it is common to speak of Surrealism as an international enterprise, all too often that map is one of European artists’ exilic itineraries and romantic projections out into the world.9 Instead, the interplay of Fani-Kayode’s and Hosoe’s work provides a powerful lens into the genuinely global ambit of Surrealism as a mediating force during the twentieth century. At the same time, what follows aims to build on what Kobena Mercer has posited as a “networked” model of diasporic practice, a polycentric model of exchange, relation, and iteration that defies more conventional art historical mappings of value and meaning.10

Death by Roses

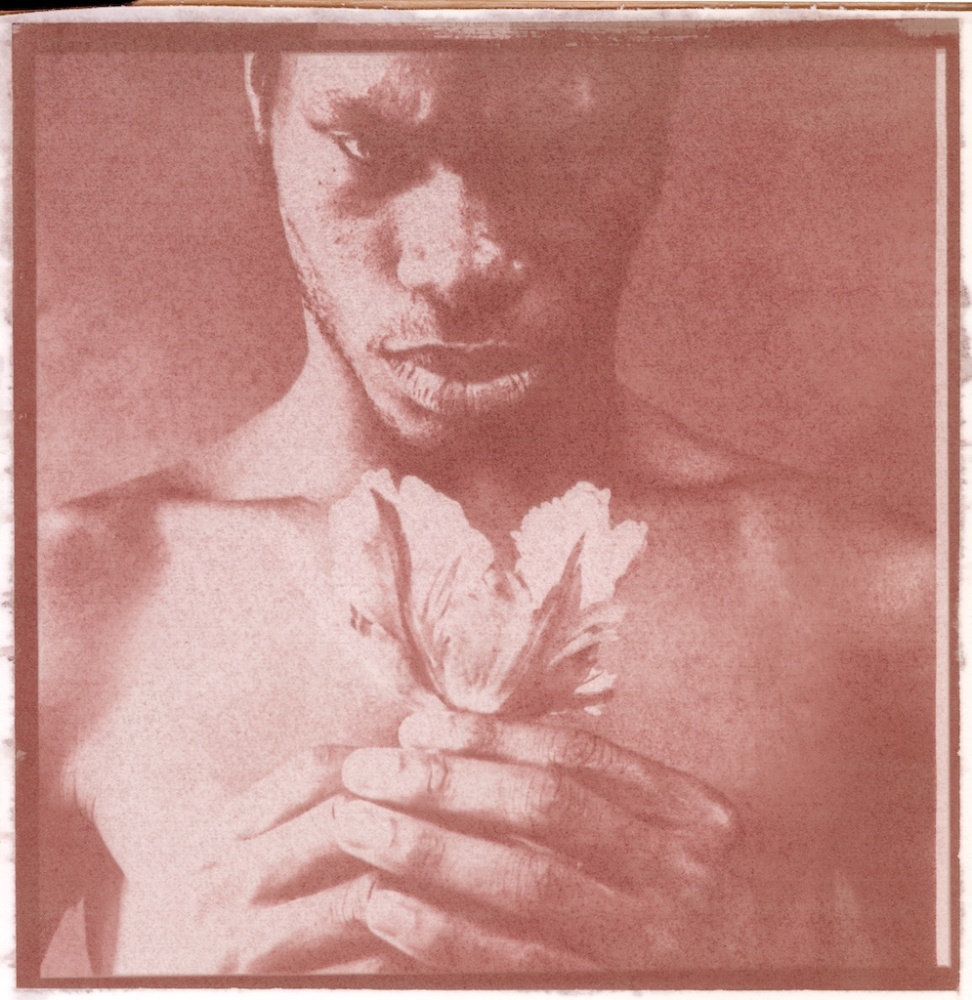

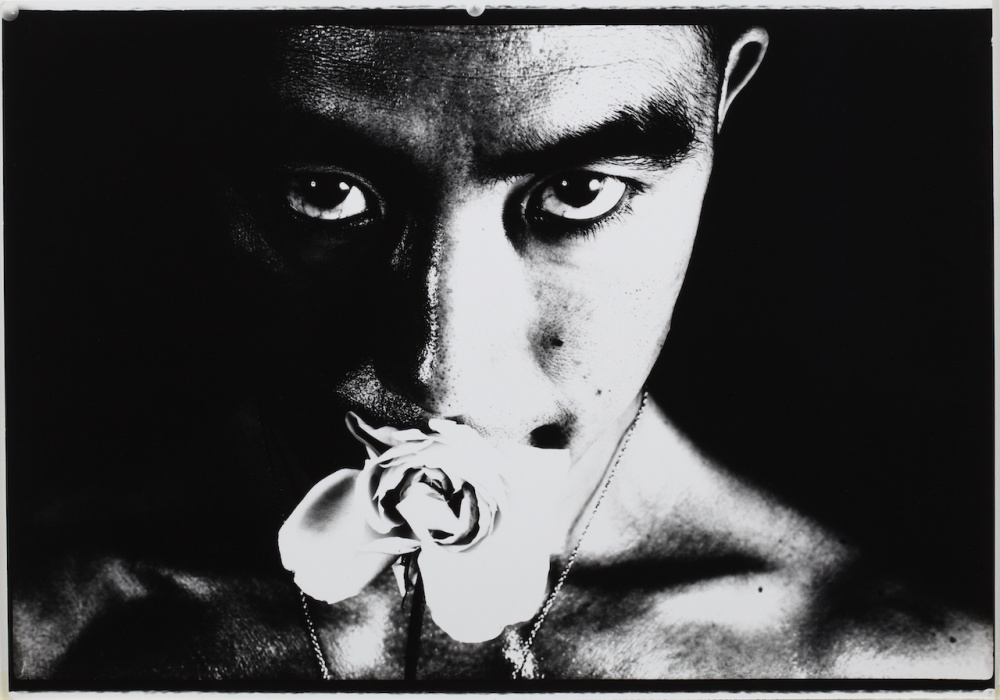

While Fani-Kayode’s photography centers representations of race and desire, there is arguably no more consistent prop therein than vegetation—fronds and leaves, lush perennials, and funereal arrangements—as in an iconic contact sheet of a man bearing a tulip in full bloom, printed in the ochre hues of gum bichromate. Yet, the pose of Fani-Kayode’s sitter is not altogether new, echoing a signature image in Hosoe’s Barakei (Ordeal by Roses), first published in 1963. Indeed, Ordeal by Roses #32 (1961) features Mishima gazing intently into the lens, his face center frame, partially obscured by the titular rose, much as Fani-Kayode’s sitter would some thirty years later. As Hosoe remarked of the portfolio in 2010, “A rose is beautiful, but it has thorns; the outside is beautiful but the inside is dangerous. That kind of symbolism was very much close to him. . . . This is a subjective portrait of Mishima, interpreted very dramatically by a photographer.”11 Fani-Kayode printed both a c-print and a gum bichromate version of his image, Tulip Boy (1989), each apparently attuned to the composition of Hosoe’s precedent. To make this connection clearer still, Hirst (who penned much of the firsthand writing on Fani-Kayode) evokes Hosoe’s photographic subject: writing of the arduousness of creating in the shadow of a plague, he notes that “I have made a place in my heart for such jokers as Edith Sitwell, Zippy the Pinhead, and Yukio Mishima.”12 A once-prolific writer, Mishima by ‡ had taken on a politically performative character that veered between camp and reactionary delusion.

Barakei was republished in 1971 and again in 1985, based on an original design by Kohei Sugiura. Enrolled in university, then art school, and living in Washington, D.C., from 1976 to 1980 and New York from 1980 to 1983, Fani-Kayode would have had access to a range of photo catalogs, both new and in reissue. Among these, it is clear from his wider body of work, were noirish portfolios of 1930s-era Surrealism and fashion photography (Man Ray, George Platt Lynes, Brassaï) and a growing body of Gay Liberation–era image making, from pulp magazines to the Apollonian black-and-whites of contemporary Robert Mapplethorpe. Within this collection, it seems likely, was the 1985 Aperture edition of Barakei (now “Ordeal by Roses” rather than the original “Death by Roses” or “Killing by Roses”), or the accompanying book for the 1974 New Japanese Photography exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, which introduced American audiences to the groundswell of art photography circulating in Japan throughout the 1960s. Among the fifteen photographers featured there were Hosoe (images from Barakei and his iconic Man and Woman) as well Kawada Kikuji and Tōmatsu Shōmei—three of the six members of the VIVO (“life”) photo agency that operated a studio and office in Tokyo from 1959 to 1961.13

The 1974 MoMA exhibition, the formation of collectives such as VIVO, and short-lived publications such as Provoke were in turn crucial for global circulation of Japanese avant-garde photography. This work was by design at variance with the formalism that typified much American photography and attuned to the dissonances of a Japanese order increasingly defined by late-capitalist mass culture and a sense of a postoccupation “Americanization,” including the circulation of modernist conventions (for example, Art Informel and Abstract Expressionism).14 Japanese photographic and film critics fiercely debated throughout the 1950s and 1960s the ratio of photojournalistic realism and object-driven images to more “traditional” Japanese artistic modes that focused on more ineffable “ideas.”15

Both sides of this debate tended to emphasize on one hand the influence of European precedents, and on the other the capacity of seemingly literal or immediate work to resonate with creative “energy.” Tōmatsu himself responded to influential critic Natori Yōnosuke’s 1960 conceptual essay in Asahi Camera, saying that “to prevent photography from becoming sclerotic, I believe we should drive away spirits that haunt ‘photojournalism’ and destroy the preconceived ideas carried in the term.”16 Ultimately, as curator Yamagishi Shoji argued, not only did most art photographers in Japan have “little regard” for high finish, they also had few outlets—such as collectors and galleries—and relied extensively on the artist’s-book format.17 At least several of the photographers in the MoMA group show adapted what European audiences would recognize as Surrealist methods (double exposure, solarization, and perspectival disorientation) and motifs, from sexual desire to the recurrence of traumatic memory. This is unsurprising, given that Japan was itself a hub of Surrealist experimentation during the years leading to the war. After two decades of state repression, such experimentation resurfaced in the 1950s.18 This was certainly the case for both Tōmatsu and Hosoe.19 The latter recalls that he was influenced by Surrealist practice since at least 1952, when he joined the Demcrato artist’s group led by Takiguchi Shuzo—the latter a friend of painter Joan Miro and a catalyst in the development of Japanese modernisms in the 1930s.20

There are many obvious symmetries between Hosoe’s photographs from this time and Fani-Kayode’s some twenty-five years later. Most obviously, they worked in the context of art publics that did not valorize their photographs. Fani-Kayode displayed almost exclusively in community spaces and niche galleries in working-class areas of London during his life, only gaining wider exposure after his death. His definitive portfolio of images, published in the United Kingdom and Germany in 1987–88, responded to a lack of mainstream visibility by relying on the circuits of queer counterpublicity.21 Yet in form and substance that book, Black Male/White Male, can also be understood as building on the model of Hosoe in his respective artist’s books Man and Woman (note the binary in each title) and Barakei.

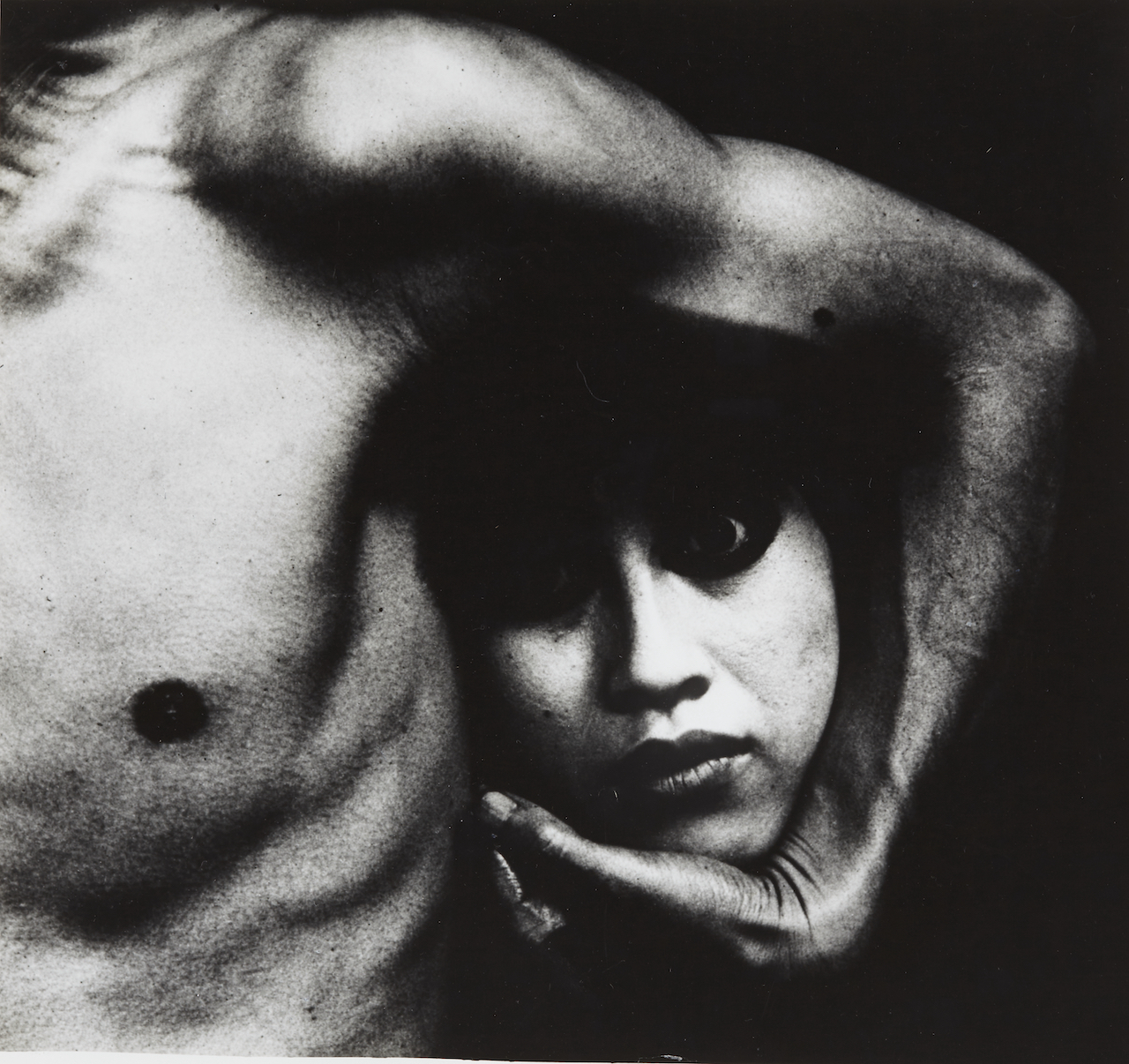

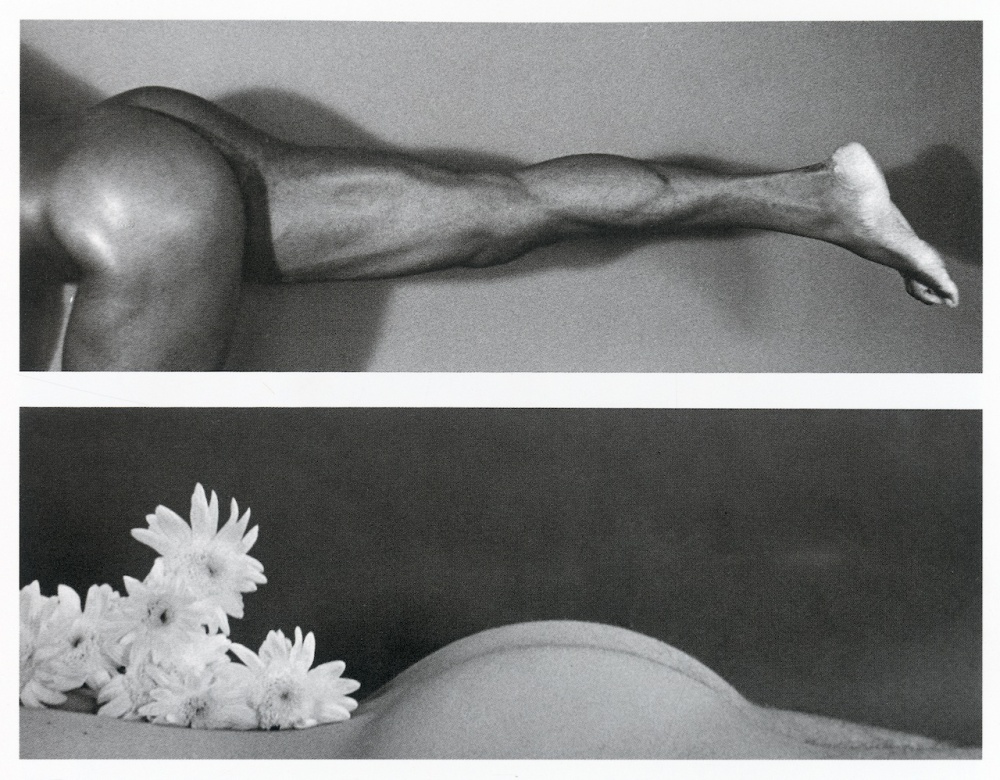

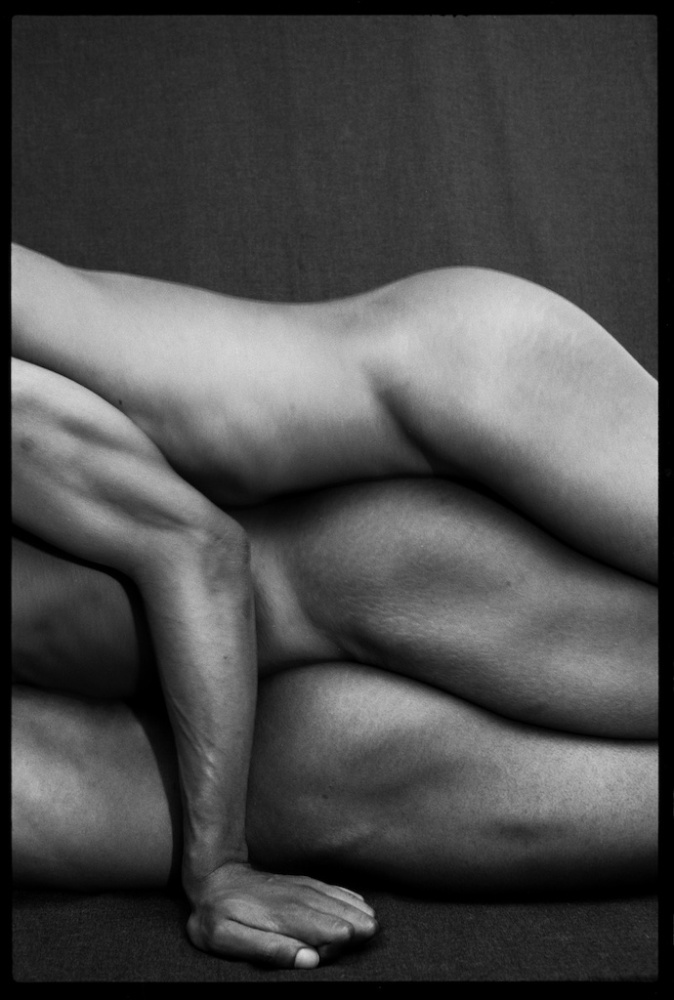

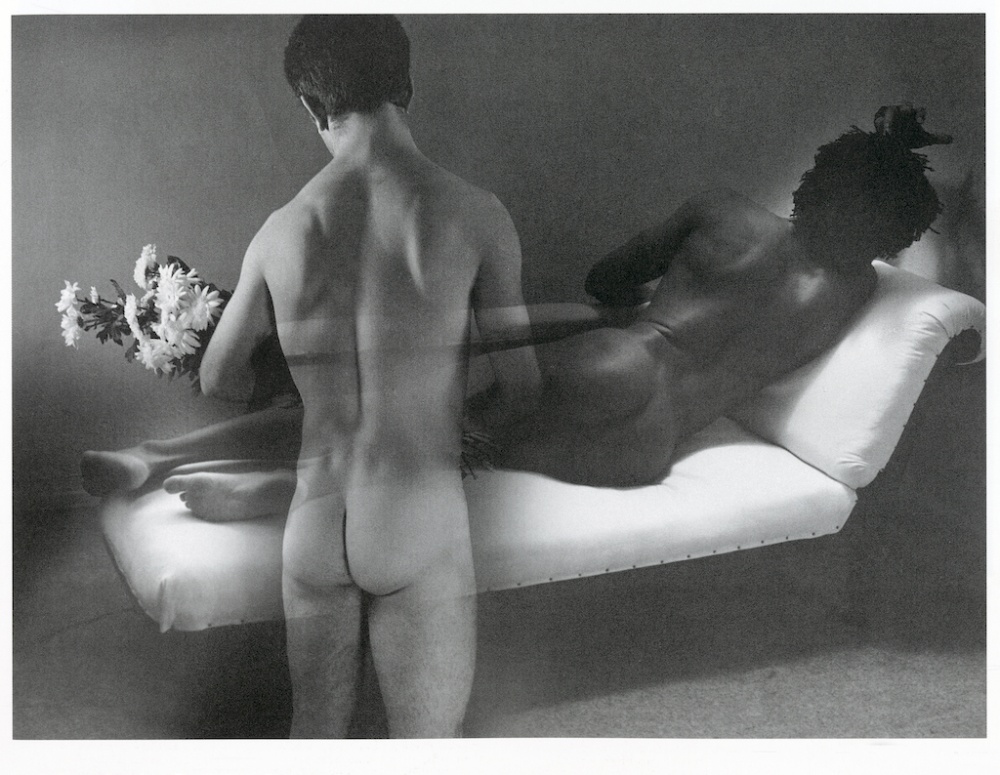

In formal terms, too, there are many instances of Fani-Kayode citing Hosoe. The rose-bearing shot of Mishima Yukio was prefigured, for one, by the second photograph in Man and Woman, a full two-page print of a woman’s face set against an inky abyss, her shadowed eyes peering at the viewer over a daisy borne in her mouth. Fani-Kayode, in turn, printed a version of Tulip Boy where the titular flower is held aloft, between the sitter’s teeth. He rests strikingly similar white flowers on the sumptuous curve of a back in Prohibited (1986–87). Hosoe’s 1959 image is playfully ghoulish, suggestive of consumption and desire, availability and withholding. Fani-Kayode’s black-and-white works from 1985 to1988 share this tonal quality—directed gazes, by turns searing and manic, or figures looks occluded by “see no evil” hands. Elsewhere in Man and Woman, legs are tangled in warped foreshortening, the bare soles of feet are revealed. A muscled arm overlays a bare breast, creating biomorphic geometries, and seeming differences collide: X and Y chromosomes, dark and light. Alex Hirst, too, saw the pages of Black Male/White Male as a crossroads of seeming binaries, of race and place, of colonial, scopic, and sexual power. Theirs was also a space of erotically interweaving subjects.22

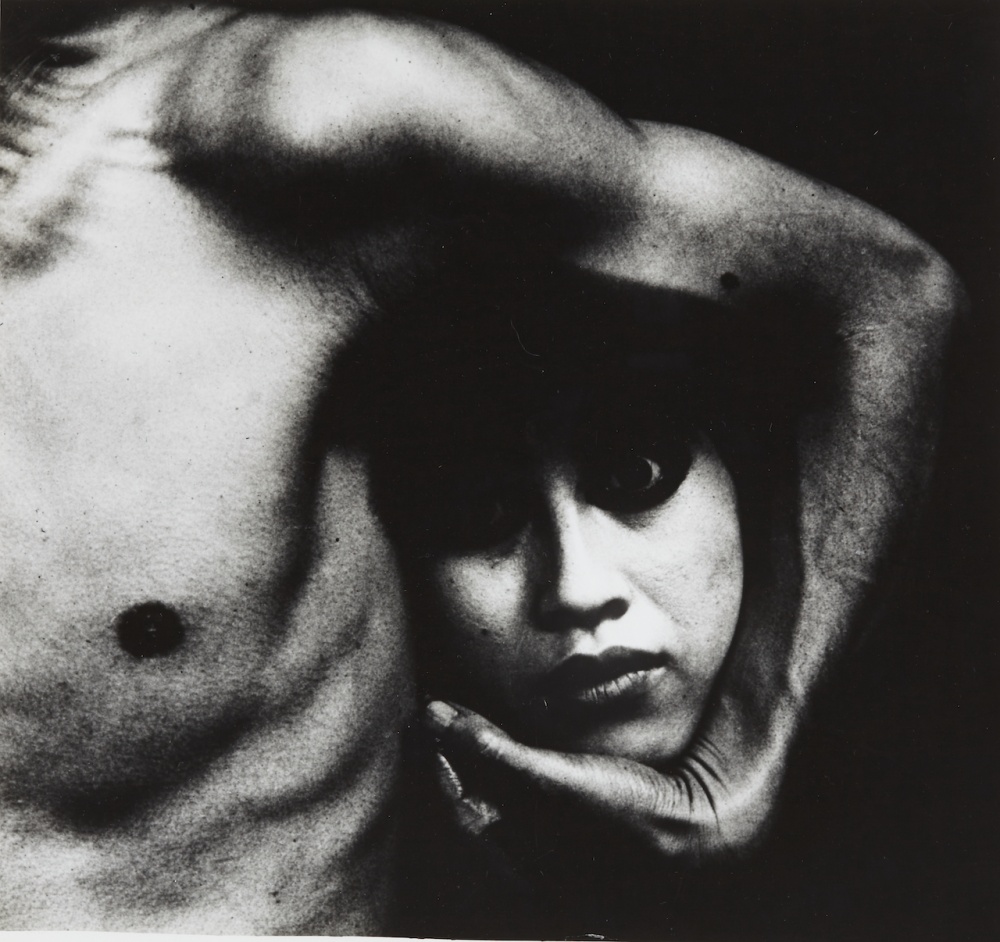

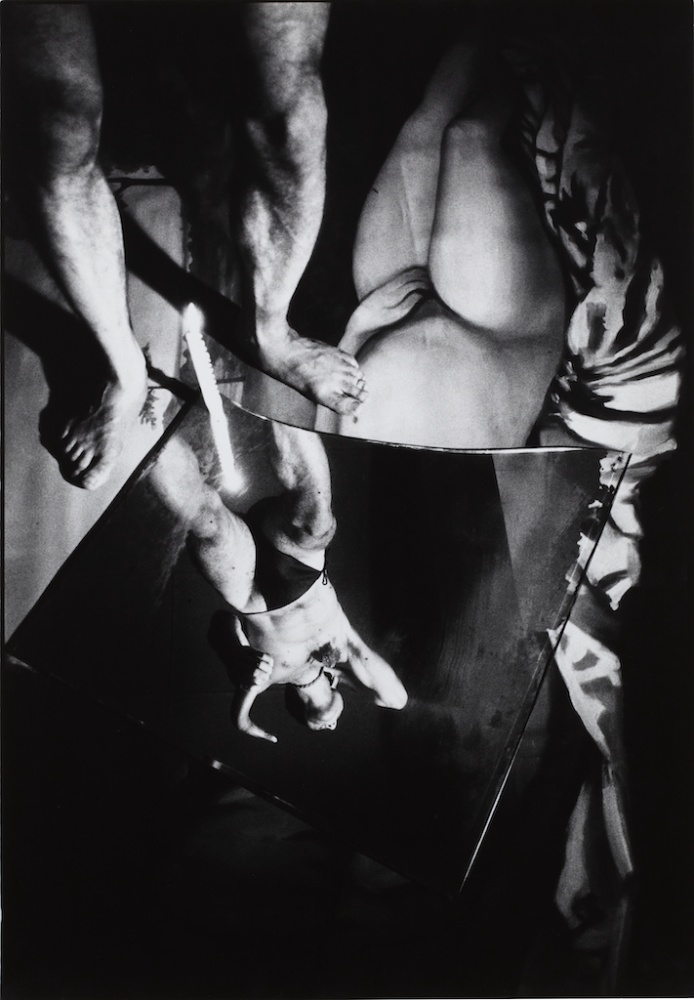

Indeed, at least three compositional motifs in Hosoe’s collection are closely limned, if recontextualized, in Black Male/White Male. In one, the upper torso of a man—all sinuous fascia and vigorous flesh—cradles a woman’s head, floating in the void as if disembodied. He is the monster in the labyrinth who suggests other unnatural substitutions, the grafting together of seeming opposites. Such emphasis on the muscled chest held in contrapposto is pervasive in Hosoe’s portfolio. Sometimes a breast appears in the frame, or the figure gazes skyward, or two hands cradle white birds close to the sternum (in Man and Woman #33). Flipping through these uncaptioned, full-bleed reproductions is to see different kinds of bodies, certainly, but also to partake in gothic atmospherics resonant in Fani-Kayode’s book. The latter’s nude bodies are folded and cropped, not to heighten their fetishistic prurience but to make them strange. And like Hosoe’s, his acephalic forms often bear metonymic heads, here by way of his Yoruban spiritual lineage: the gelede mask, or an Ifé bronze, both sanctified forms desublimated and brought into collision with new vectors.

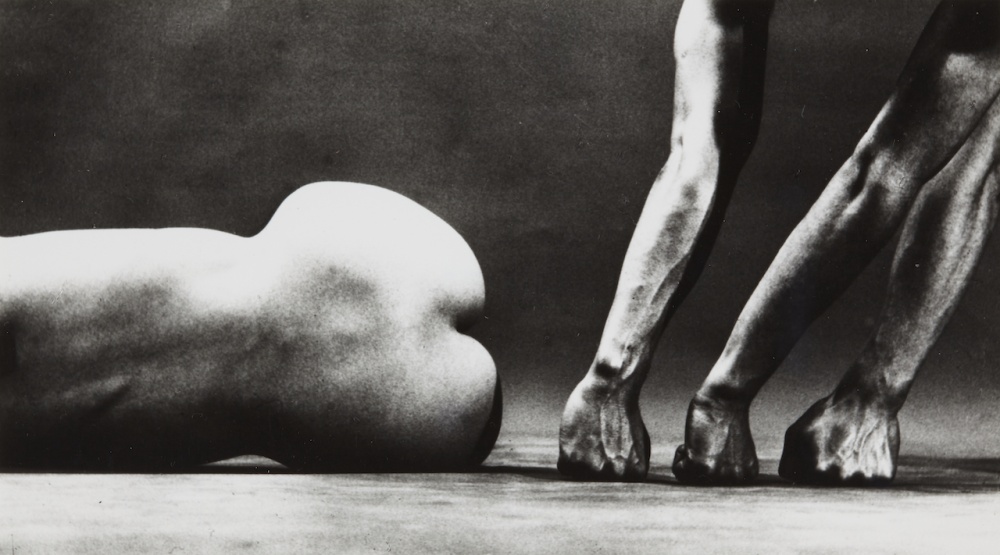

Perhaps the most famed scene from Man and Woman shows a sitter’s lower back and curvaceous posterior, shot from behind. This stereotypically feminine form—overt in its voyeuristic charge—renders the subject as object, so much flesh on a slab, ready for delectation, visual or otherwise. She appears throughout the book, in a play of Edenic temptation, as site of communion and transubstantiation. In the two-page sprawl of Man and Woman #24, the same body is approached in the right register by three columnar forms, a man’s arm with clenched fist driving into the floor. This version implies a percussive step and the repetitive pulsations of the multiple exposures by which this “three-legged” form appears to have been realized.23 It is chthonic in the extreme, amplifying the sense of bodily fragments made vital.24

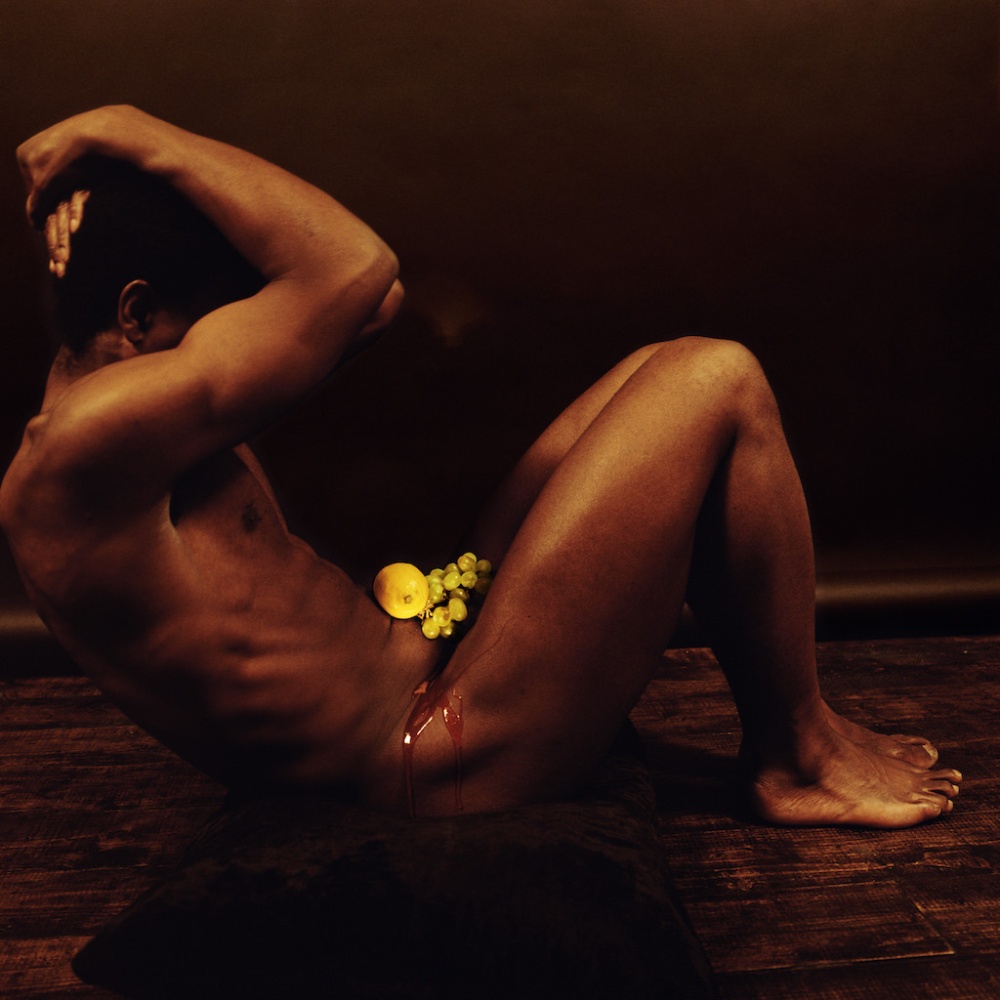

Paging through Fani-Kayode’s black and whites also finds muscled extremities in stress positions or overlaid multiplicity. In both cases, for all of the photographs’ suggestiveness, they are each oddly obscure, redolent of sexuality but never graphic, open about the sex of the body but ambivalent about gender.25 Such ambivalence is more pronounced still in the Barakei project, wherein Mishima’s loins are carefully clothed, and his interlocutors’ genitalia clasped underhand. For his part, Fani-Kayode’s fragmented bodies were almost always desexed through a tucking here, an arched back there. They were often frontally draped by a series of props, be they flowers and crucifix, medium-format camera, or taut raffia. For the 1989 session with Taylor at Railton Road, the desired phallus was bowdlerized with gold paint and a supportive filament truss.

For all of the stylistic and psychic resonances to be found, it bears reiterating that Hosoe and Fani-Kayode were playing with different stakes: one meditating on sex and gender in the context of a deeply patriarchal society undergoing the convulsions of so-called modernization in the wake of the “year zero” of 1946; the other mediating the three strands of his outsiderdom, as he noted, in terms of race, queerness, and class.26 As many of the key historians of Fani-Kayode’s work have observed, the artist’s many intentional elisions and defamiliarizations also sought to short-circuit the fetishistic gaze in relation to Black bodies and especially the Black phallus. Yet, there is power in the look—of the spectator and the camera—and in 1960s Japan, Hosoe would have wielded authority of one kind over his sitters; Mishima another still, working as he was to rebrand himself, to develop a personal mythology through his collaboration with the former (women, in Barakei, are functionally props, foils, and counterpoints). Whatever agency the camera granted him, Fani-Kayode also saw his work as collaborative with the various artists, writers, activists, and models with whom he worked. He actively sought to reformulate the strands of scopic power by which modernism had been woven over the previous century.

In short, the connection I am drawing between Hosoe and Fani-Kayode is not about repetition or mimicry as such: Fani-Kayode apparently cited Hosoe, but both synthesized elements of their own cultural inheritance with Surrealist tactics, simultaneously bypassing and repurposing the transatlantic interwar avant-garde. Indeed, both artists’ books call to mind Hal Foster’s contention that Surrealist practices “intuit the uncanny discoveries of psychoanalysis,”

sometimes to resist them, sometimes to work through them, sometimes even to exploit them: i.e. to use the uncanniness of the return of the repressed, the compulsion to repeat, the immanence of death for disruptive purposes—to produce out of this psychic ambivalence a provocative ambiguity in artistic practice and cultural politics alike.27

Thematically, much of Fani-Kayode’s work in the 1980s and much of Hosoe’s from the 1960s work to blur self and other, the object and the subject, waking life and the fantastic, to limn death and desire in legibly Surrealist ways but operating from different geographic centers, responding to different traumas, wherein the “postwar” or the “postcolonial” were figments of a naive, Eurocentric imagination.28

Spirit Photography

Both Fani-Kayode and Hosoe were aware of European Surrealist precedents. As early as 1953, Japanese avant-garde photographers referenced the work of Man Ray in debates about the future of the medium, marking a period of sustained exchange with post-Surrealist modes of abstraction in Paris and New York.29 Hosoe was attuned to literary modes in particular but hewed to the creative (rather than documentary) potential that the Japanese artists had gleaned from the movement—he later noted that whether Barakei was surreal or not, it was his experiment in “the transience of vision over the conventional way of expression.”30 In turn, Fani-Kayode’s citations and inversions of the work of artists such as Man Ray and Brassaï and techniques such as automatic writing or solarization are well documented. He likely came into contact with these earlier moments in Euro-American photography by way of landmark exhibitions at London’s Hayward Gallery, such as the omnibus Dada and Surrealism Reviewed in 1978 and the photography-centered Amour Fou in 1986.31 The catalog for the latter was a key site in which Rosalind Krauss distilled her ongoing “recuperation” of the genre (and its theorization by way of Georges Bataille) for a wide audience.32 As Sandra Zalman has argued, however, such a recentering arrived at an inopportune time: whether one believes that European Surrealism was a vital force within modernism or a subver-sive avant-garde working at its edges, by 1986 many of its currents were subsumed into a broader Euro-American postmodernism that blunted its transgressive force.33

In the main, the postmodern is an interpretive frame primarily interested in the linguistic—the symbolic—rather than the more somatic, metaphysical, or apotropaic concerns on which Surrealism was often predicated. A corollary, then, is that even as Surrealism returned in curatorial and critical discourse in the late twentieth century, the terms were typically retrospective and partial. On one hand, this meant that even massive exhibitions at the Hayward featured a roster almost exclusively composed of white, European men, its “global” ambit a version of Paul Éluard’s Surrealist map of the world, which expanded not so much the subjects in play but the range of their objects of fascination.34 On the other hand, routed as Fani-Kayode and Hosoe were through very Eastern Asian and Global Southern peripheries newly centered in that map, their work can be seen less as belatedly building on a European precedent but drawing parallel conclusions from the same source material.

This is not to say that artists from Japan or the African diaspora did not share techniques or compositional strategies with European avant-gardes. For instance, both Tomatsu and Hosoe adapted techniques later charted in the Amour Fou show, their photographs echoing the preoccupations of Bataille and his several journals: occult textures, the recurrence of bestial and insectoid forms, the corpus distorted, automatized, or decapitated.35 Moreover, it is diffcult to view the recurrence of the cropped torso and arachnid arms in Man and Woman and not also see the repetition of similar gestures in the hands of Brassaï and his phallic nudes of 1931–34.36 In both cases, the seemingly mimetic function of the camera is revealed to be a destabilizing one, upending closures of sex and gender and inviting wider interpretation through the lens of castration and metonymy (or later by way of the desublimatory ambivalence of the “part object”).37. Similarly, even before Fani-Kayode’s death, his work was conjoined with Mapplethorpe’s, contrasting their deployments and elisions in the Freudian terrain of fetishism. But if Fani-Kayode and Hosoe (as well as Tomatsu and Mishima) can be understood as operating in relation such interwar precursors, that relation can only be understood beyond the terms of mere citation, enmeshed instead in a more multicentric and dialogic approach, exemplified by the haunting, polysemous tableaux Barakei (Ordeal by Roses) #16 and White Bouquet (1987).

An analogy can be found in the writing of Yoshihara Jirō and the Gutai Art Association, which by 1952 had harvested elements of the early Bretonian program, especially its use of the manifesto/periodical format and a reliance on automatism as a world-altering force. Nonetheless, Yoshihara was careful to distinguish the association’s work from European precedent. Although he notes symmetries in the foregrounding of the unconscious and, too, in the formal approaches of 1950s-era Art Informel, he cautioned that their context and meaning should not be conflated. Instead, he outlined a Gutai emphasis on materiality itself, often precisely in terms of exorcism—of chasing away a moribund history of the French avant-garde. In its place, when “matter remains intact and exposes its characteristics, it starts telling a story and even cries out. To make the fullest use of matter is to make use of the spirit. . . . Art is a site where creation occurs.”38

A similar sense of “spirit” imminent in photographic practice was crucial to Hosoe’s and Fani-Kayode’s processes, and it is why they resist easy categorization along the lines of the conventional modernism/postmodernism mode of historicization. In short, neither photographer adapted Surrealist strategies uncritically, and they did not take the sort of work celebrated by writers such as Krauss or Dawn Ades in the 1980s at face value.

Hosoe was immersed in complex debates around tradition and progress in postoccupation Japan; Fani-Kayode looked to Europe with an eye toward subversion and play, adapting them to the spiritual techniques to which his family was heir, a reductive version of which occupied Surrealist journals from afar fifty years earlier. Such triangulation was avowedly part of his practice. As curator Mark Sealy has argued, what

Fani-Kayode was attempting to communicate was of no concern to the then current European photographic trends. . . . The ethereal world was as important to Kayode as the tangible world. In his work he is inviting us to play with him in the gray zones between black and white, gay and straight, acceptance and taboo. This work was the beginning of a constructed twilight cross-cultural zone, a kind of Never Never land where “reality” is a stranger.39

Sealy’s emphasis on the imminence of two kinds of worlds to be excavated by the camera—the ethereal and the tangible—is as important as his observation that Fani-Kayode saw his task as creating provisional zones that did not yet exist. This is where Hosoe’s methods likely proved essential for Fani-Kayode, even at a cultural and temporal remove.

Fani-Kayode seemed to want something more than to litigate cultural meaning through the surface-level effects of symbolic appropriation. He sought out a version of photography that unveiled or initiated instances of spiritual communion, perhaps akin to the “mounting” of initiate by deities documented by, for example, Maya Deren and Ito Teiji’s film Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti, released in 1985 (though filmed more than thirty years earlier). As he bluntly stated, “[my] reality is not the same as that which is often presented in Western photographs. . . . I try to bring out the spiritual dimensions of my pictures so that concepts of ‘reality’ become ambiguous and open to interpretation. This requires what Yoruba priests and artists call a ‘technique of ecstasy.’” He continues, noting his desire to create new types of images that “undermine conventional perceptions and which may reveal hidden worlds.”40 This was not metaphor or euphemism.

Whereas Fani-Kayode was the scion of a family who were keepers of sacred divination practice, Hosoe, born outside of Hiroshima in 1933 to a Buddhist priest, was himself raised in a spiritually infused environment. By 1960 he developed a synthesis of Japanese and European approaches to the medium, coalescing in the collaboration with Mishima, providing the latter with a chrysalis for a new self and the ground wherein it might be realized.41 Such an approach would have resonated like a beacon for Fani-Kayode and Hirst two decades on. Their stylistic catholicism was to an extent a matter of survival in a social and art world landscape that had little room for them. As they wrote in 1989:

At other times, in other places, and with other means, people have approached the mysterious aspects of life with respect. Using their imagination and their practical skills they have developed systems of communication between the spheres of their understanding and the forces which are beyond it. They have not been able to avoid great public and private calamities but they have been able to prepare themselves in certain ways, spiritual and material, for the unexpected.42

These words, it bears reiterating, were written at the height of the AIDS epidemic, and that stanza ends with the reminder that one “can never rely entirely on the kindness of strangers,” for example, the National Health Service, pharmaceutical companies, or multinational corporations that controlled the research and development of potentially lifesaving treatments. If the Black Male/White Male portfolio explored the terrain of desire and the uncanny in the affective register of the gothic, the Yoruban “technique of ecstasy” was increasingly rephrased in the works of 1988–89 as a process of cultivating “ecstatic antibodies” as a talismanic altar against sickness. For that, Fani-Kayode and Hirst would need a spiritually infused approach to the medium that went beyond the realm of stylistic rehearsal or semiotic appropriation. Hosoe’s project with Mishima was precisely that model.

Beyond the Frame

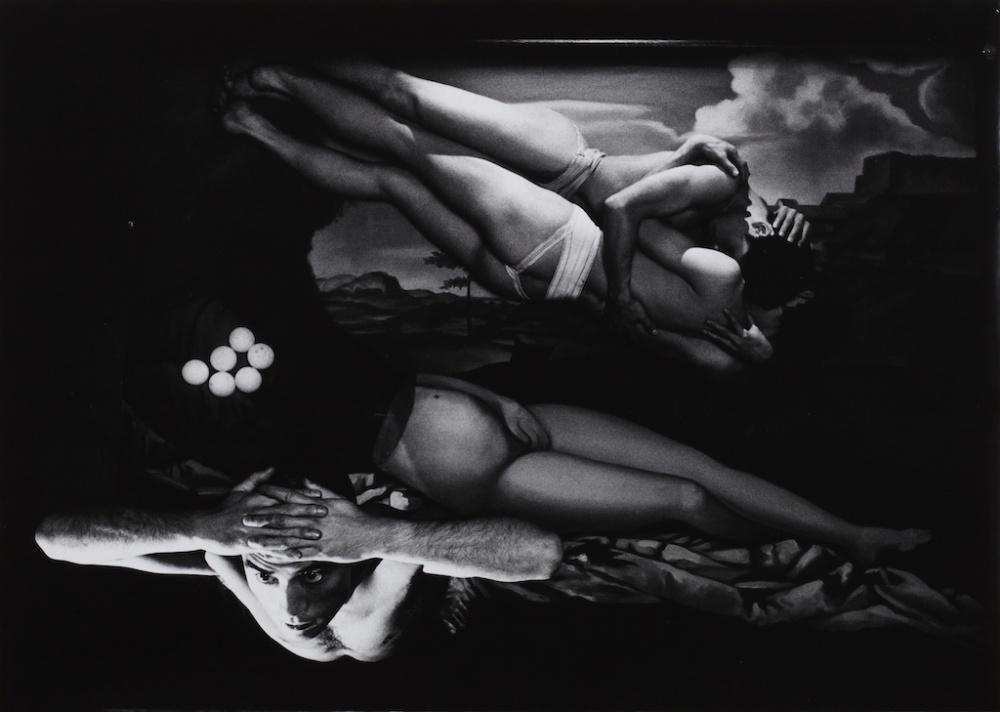

This essay began with a cascade of linked images—a woman with a daisy, Mishima with a rose, Fani-Kayode with a tulip—and went on to suggest thematic and tactical resonances between European Surrealist photography in the 1930s and artists’ books produced in 1963 and 1987. Indeed, Barakei, with its use of solarization, multiple exposure, and axial rotations, fits the bill. So, too, does it square with abiding Surrealist engagements with the haunted house and the game of chance.43 For the shoot, Hosoe and his assistant Moriyama Daidō joined Mishima at his house, inviting the Nobel Prize–winning author to use objects from his own space to create a self-portrait. The results were visceral, charged with a sense of foreboding, electrified by Mishima’s narcissistic-erotic energy. It is often commented that the project reads as highly theatrical, bordering on the dreamlike.44

While Barakei is performative in the extreme, the images are not conventionally directorial.45 That is, there is little artifice here but instead something stranger—the sense that one has stumbled across an arcane ritual. Indeed, Hosoe remembers the six months as “a crazy scene,” in which he and Moriyama goaded Mishima to ever greater extremes of intensity—the first 35mm photograph shot from above, with Mishima driving a wooden hammer into his own temple. Hosoe “wanted to break the ordinary concept of the object or subject.” He told Mishima the goal was nothing less than to photograph life and death itself.46 Certainly, invocations of life and death abound: from the fragility of the namesake roses therein to the recurrence of Renaissance painting as backdrop, such as Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1485) (in, for example, Barakei [Ordeal by Roses] #19) or Titian’s Venus of Urbino in Barakei (Ordeal by Roses) #16, “sandwiched” into the exposures.47 Bodies are fragmented and contorted like so many doll parts, uncanny exquisite corpses; in #33 Mishima seems to lie at rest, leaf on torso, thorny rose stem alighting on his jugular vein. In another, double exposure is used to suggest a face, ringed by hair but damaged beyond recognition. Crucially, Hosoe cautions readers that the series was not meant to presage Mishima’s death but rather to engage the author in “subjective documentary.”48

While the symbolism here is at times macabre, it can also be seen as creatively regenerative, and Mishima’s body appears again and again as a kind of physical altar. Barakei (Ordeal by Roses) #38, stages its subject in deep trance—perhaps headed for interment—but it also festoons him with floral life, as one would sites of pilgrimage and veneration, like a saintly cabinet. An accompanying photograph (#18) catches Mishima’s lower body, loins obscured by a precarious black cloth, reflected in a mirror resting atop a nude woman’s partial form. A candle burns in the center, axially connecting to Mishima’s own groin, its sacred flame a metonymic substitute for a “castrated” body. It is worth making two points at this juncture. First, the majority of Fani-Kayode’s color series, for example, Nothing to Lose from 1989, pose his sitters in precisely this manner—rendering the body as bearer of flowers and fruit, their juices (for him, always an ambiguous blend of bodily or gustatory secretions, of wine, milk, honey, or divine water) running across muscled torsos. An earlier, hand-tinted work, Sonponnoi (1987), frames a seated figure, headless, bearing a lighted cluster of candles, occluding and sacralizing his phallus. This body is spotted like a pox sufferer and has become an altar itself.49

Second, Barakei opened still another door for Fani-Kayode. For Mishima, photography was more than document, more than index—it had something like its own subjectivity, the capacity to act as witness, one necessary to initiate the ritual and provide testimony (shogensei).50 According to art historian Ignacio Adriasola, Hosoe’s camera served, for Mishima, as a “machine” for incantation: “the world I was taken to by the sorcery of his lens was abnormal, twisted, ridiculous, grotesque, savage, pansexual; however, in this world one could also hear the murmuring of a clear, cool stream the undercurrent from within the unseen side of a gutter.”51 Mishima describes his time with Hosoe and Moriyama in much the same way as Taylor, the model who sat for Fani-Kayode and Hirst’s Golden Phallus series in 1989, recounts his own. Similarly, Mishima recalled that his own spirit and mind became “redundant” in front of the camera, giving way to a state of “exhilaration”52—a little death of the self, a ritual ordeal, akin perhaps to Fani-Kayode’s “technique of ecstasy.”

Radiation Ruling the Nation

Fani-Kayode—artist, activist, exile—wrote precious little about his work, largely leaving that task to Hirst, the editor and novelist, as early as 1987. While the art historical case connecting Fani-Kayode and Hosoe is plausible in terms of visual affinity, it is also worth reiterating here that Hirst mentions only Mishima by name, which raises some important questions. Specifically, in their individual careers and in collaboration, Hosoe the photographer and Mishima the writer responded directly to the twin traumas that haunted postwar Japanese life and the so-called economic miracle that defined it. The one was the legacy of the nuclear blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which created a psychic rupture between life before and after “day zero” and spread the invisible poison of radiation, which lurked on a molecular level in the Japanese body politic for generations.53 The other was the memory of American occupation and its subsequent investment in a boom economy that provided material security at the expense of traditional cultural identity. Some aspects of this trauma played out in popular culture—for example, in films such as Godzilla (1954).54 Given its sustained engagement with questions of memory and trauma, Surrealist-derived practice, of course, would be an obvious path for artists in the 1950s and beyond.

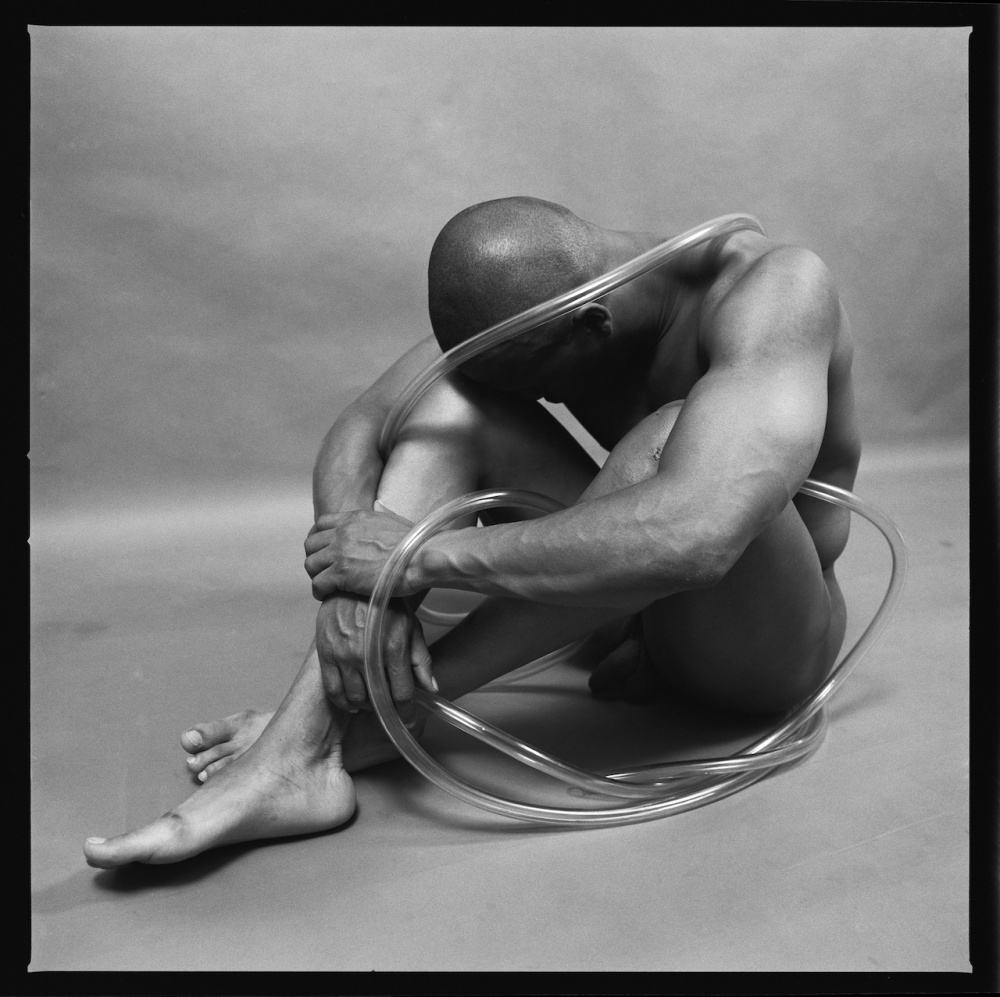

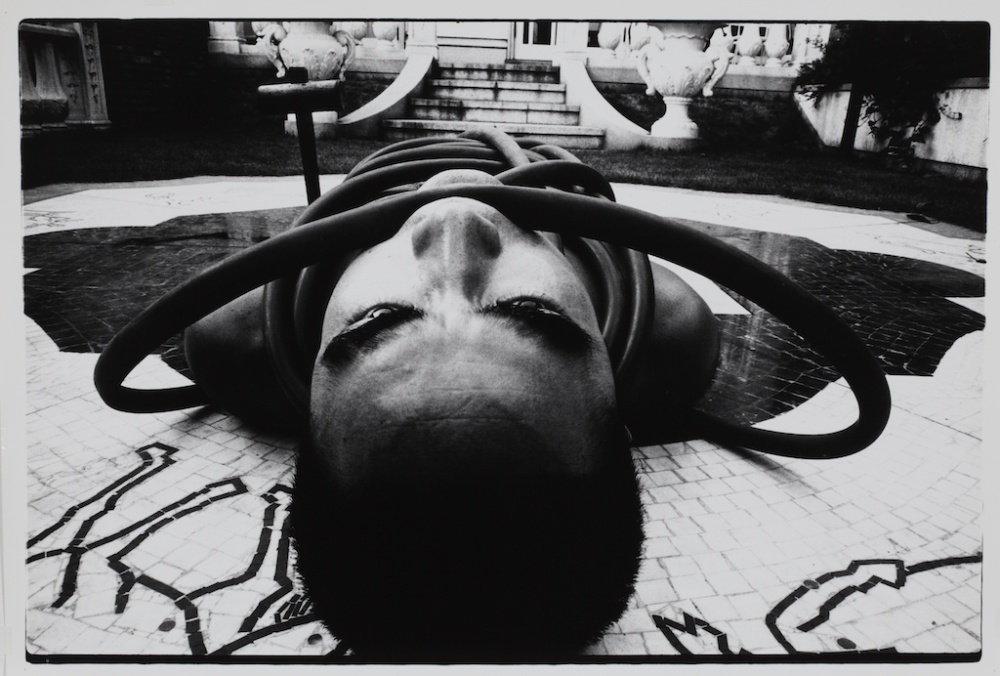

Hosoe and Mishima responded to these challenges in distinct ways, though often using similar imagery. In one potent composition, Mishima is framed at the ground level, bound in coils of rubber tubing amid the dizzying expanse of his atrium. Fani-Kayode employed a similar material in his Abiku series of 1989. Its title is a reference to his given name, “Rotimi,” which translates to “stay with me”—a name which refers to the abiku, children believed by the Yoruba to be predestined to die before adolescence. In these works, rubber tubing thus takes on both umbilical and deathly connotations. Death seems to have stalked both Mishima and Fani-Kayode from an early age, and both sought through art to either transcend it or arrest its ineluctable wasting process.55 Yet, where Fani-Kayode avowedly defined himself in opposition to the Nazi regime and the parallels he saw in the homophobia of his era, Mishima took a different tack. During those final years, his politics crystalized in the form of neofascistic nostalgia, which posited an Americanized Japan, delinked from its martial past, as a castrated society. Such “lack” for him could be compensated with a rightward lurch and, on the somatic level, a fascina-tion with a honed masculine form.56 Such phallocentrism cannot be couched merely in terms of Mishima’s apparent homosexuality: as J. Keith Vincent has shown, Mishima’s queerness was still debated in Japan decades later, and his first “gay” novel, Confessions of a Mask (1949), seemed to corroborate a regressive narrative of homosexuality as a developmental stage on the road to heteronormativity. Barakei, here with its scenes of near-nude men and women, there with its merging of two men in jockstraps, presents an ambivalent narrative of desire.57

By contrast, Fani-Kayode viewed himself in cosmopolitan and antifascist terms in the one essay attributed to him.58 So, too, did he seek out earlier models of liberation-era visual culture to make overtly “gay photography.” And while Mishima’s 1951 Forbidden Colors did finally do the apparently autobiographical work of sketching the gay Tokyo underground, Mishima’s later paramilitary machismo seems at odds with Fani-Kayode’s ambivalent play of genre and careful labor of satirizing, deflecting, or deflating phallocentrism, especially in the register of fetishism and castration anxiety.59 For all that, there must have been some value for the photographer, seeing non-Eurocentric examples of colonial and postcolonial queerness mediated through creative practice. As Sealy has argued, Fani-Kayode was alienated in many ways from the city and the dominant culture where he found himself—he was deeply conscious of the “subtle forms of postcolonial racism that are endemic to Eurocentric institutions.”60 Importantly, in 1980s England, “Blackness” itself was a discourse that comprised Asian as well as Black Atlantic identities.

From this perspective, Fani-Kayode would likely have been drawn to forms of Surrealism that emerged from a non-European vantage. For their part, Hosoe’s and the VIVO collective’s projects of the 1950s were wary of the postwar order, eschewing formalism in favor of dissonant avant-garde strategies. Tōmatsu, for instance, turned in the early 1960s to multiexposure montages of found objects, landscape, and popular culture that produced jarring skeins of photographic abstraction, even as Hosoe composed Barakei.61 The more straightforward works by both artists plumbed broad humanistic depths, with unsettling results: Tōmatsu’s “sandwich men” examined Kabuki performers (men in feminine masquerade) in Tokyo; and both pursued the wreckage of the atomic blast, in the form of distorted still life, or the bodies of the hibakusha (survivors), their keloid scars and glassine corneas, and genetic complications passed to the next generation. Hosoe returned repeatedly to Hiroshima, including for a 1985 collaboration with psy- chologist Betty Jean Lifton that surveyed the imprint of devastation on the corpus and the landscape. She argues therein that “the legendary place that you seek is not located on a map. It is a state of mind.”62

That state of mind—the lingering trauma of the blast, the wariness of living in an age of mutually assured destruction, stalked by invisible cancers—underscored a national consciousness in 1960s Japan but also a global consciousness until at least 1989. The 1980s was a decade marked by nuclear brinksmanship and a growing antinuclear movement in the West. Such disorientation lent itself generally to photographic registers sensitive to imprints of the body, the play of chance of operations, or the decomposition of visual order.63 In the Japanese context, as Miryam Sas has shown, the experimentalism of the 1960s across visual and performance arts actually built on a robust foundation in place by the 1920s and 1930s, and elaborated after the war in the ankoku butô (dance of darkness) or Butoh. As Sas notes, Butoh shared with Surrealism an “anti-philosophical, anti-conceptual search for a terrifying limit-moment, a breakdown of symbolic systems.”64 Significantly, Hosoe was explicitly inspired to make Man and Woman after seeing a Butoh performance by Hijikata Tatsumi, who served as one of the subjects in the series. Hosoe described the process not as mere documentation of performance but as a dance of its own sort, a new hybrid form of drawing energy into the world.65

Third Way

When Fani-Kayode and Hirst looked to Hosoe from the horizon of the mid- 1980s, symmetries abounded. Like Hosoe, they lived in a society driven by a cult of consumerist corporatism; they worked under threat of nuclear holocaust; and they feared an insidious, little-understood scourge. The latter was not the persistence of cellular mutation run amok but a virus that also left carcinomas on the flesh, that waited in the body and cut men down in their prime. As filmmaker Derek Jarman once remarked, to be queer in those years meant to be living in the midst of plague.66 Death was only a matter of time. By way of their artist’s book, Hosoe and Mishima suggested a “third way” of adapting Surrealism, for a generation in the 1980s primed to return to its traumatic preoccupations.67

If Fani-Kayode enjoyed the benefit of hindsight in looking back over the horizon of the midcentury, he also shared a method with Hosoe. Their Surrealism was not a semiotic rehearsal of the so-called original avant-garde at the moment of its institutional recuperation. Nor was it a simple elision, returning to more familiar precedents in Japanese theater or Yoruban cosmology. No revivalists, they each mediated earlier tactics through their collaborative, performative studio practices and, effectively, in relation to each other. Both, nonetheless, insisted on art’s capacity to encounter a haunted life, to transform the world by cultivating creative energy. If earlier articulations of Surrealism insisted on ruptures with academicism in favor of the freedom of the libidinal, Hosoe’s and Fani-Kayode’s simultaneously explored and resisted the specter of thanatos overpowering eros. They did so by arraying recognizably photographic strategies drawn from a rich geographic and temporal sediment. Reaching to Surrealism’s gothic inheritance, they took death as a given, seeking renewal in an apotropaic art that was less postmodern than premodernist—a return to that which had been long repressed.

Hosoe collaborated with dancers time and again, inspired by artists working in a parallel mode, reconfiguring traditional Japanese expression for the post-1946 landscape. Fani-Kayode, too, relied on gender-ambivalent forms of masquerade that blurred the lines between self and other, this world and the next. These respective collaborations opened on to a different kind of shared project, between artists working thousands of miles apart, both responding in their way to original sins of the twentieth century, from fascism to colonialism, and the long shadows that earlier violence cast into the future, across generations. It is by now taken for granted that Surrealism played out across a global stage. But who were the protagonists of the story, and whose psychic map have we long foregrounded? The above has taken seriously Ming Tiampo’s wariness of “expanding the canon by inserting voices from outside the West into a western narrative.”68 Instead, it reorients the transgressive force shorthanded as “surreal” and gives credence to the experiences of the long-overlooked artists who forged unexpected linkages, channeling that force to reckon with a specter of death that suffused the twentieth century.

The sizes of the images of Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s works reproduced in this text are variable, and were printed at different scales at different times, both during the artist’s life as well as when the photographs were printed posthumously.

Ian Bourland is assistant professor of global contemporary art history at Georgetown University and contributing editor of frieze. He is the author of Bloodflowers: Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Photography, and the 1980s (Duke University Press, 2019) and Massive Attack’s Blue Lines in the 33 1/3 series (Bloomsbury, 2019).

- Fani-Kayode received initial scholarly attention in this journal, in Steven Nelson, “Transgressive Transcendence in the Photographs of Rotimi Fani-Kayode,” Art Journal 64, no. 1 (2005): 4–19. See also Kobena Mercer, “Mortal Coil: Eros and Diaspora in the Photographs of Rotimi Fani-Kayode,” in Over Exposed: Essays on Contemporary Photography, ed. Carol Squiers (New York: New Press, 1999), 183–210; and Evan Moffitt, “Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s Ecstatic Antibodies,” Transition: The Magazine of Africa and the Diaspora 118 (2015): 74–86. ↩

- Robert Cozzolino, “Introduction: America is Haunted,” Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art, ed. Cozzolino (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021), 9–22. ↩

- Robert Taylor, “A Eulogy for Rotimi Fani-Kayode,” Body Politic (unpublished, ca. early 1990s), unpaginated. ↩

- Robert Taylor, correspondence with the author, August 2017. ↩

- W. Ian Bourland, Bloodflowers: Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Photography, and the 1980s (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019). ↩

- This was initially articulated in André Breton’s “Manifesto of Surrealism” (Manifeste du surréalisme, 1924) and especially his Mad Love, trans. Mary Ann Caws (Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 1988). ↩

- See Brent Hayes Edwards, “The Ethnics of Surrealism,” Transition: The Magazine of Africa and the Diaspora 78 (1998): 84–135; Robin D. G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002), 157–72; and Samantha Noël, Tropical Aesthetics of Black Modernism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021). ↩

- Unless specified by the artist, Japanese names appear here with surname first, then given name. ↩

- One might consider this a corollary history to an ongoing history of global affinities/appropriations of imagined aspects of Japanese and East Asian culture (e.g., japonisme). See Samantha Kavky, “Max Ernst in Arizona: Myth, Mimesis, and the Hysterical Landscape,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 57–58 (Spring–Autumn 2010): 209–28; Saloni Mathur, “A Retake of Sher-Gil’s Self-Portrait as Tahitian,” Critical Inquiry 37, no. 3 (Spring 2011): 515–44; and Katharine Conley, “Value and Hidden Cost in André Breton’s Surrealist Collection,” South Central Review 32, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 8–22. ↩

- Kobena Mercer, “Flowback—How Africa Is Redefining Today’s Diaspora,” James A. Porter Distinguished Lecture, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Washington, DC, April 16, 2021. ↩

- Eikoh Hosoe, quoted in Yseult Chehada, “Eikoh Hosoe on Barakei,” video recording, Aperture Foundation, May 5, 2010. ↩

- Quoted in Bourland, Bloodflowers, 237 ↩

- John Szarkowski and Shoji Yamagishi, eds., New Japanese Photography (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1974). ↩

- See Miryam Sas, “The Provoke Era: New Languages of Japanese Photography,” in Sas, Experimental Arts in Postwar Japan: Moments of Encounter, Engagement, and Imagined Return (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 180–200; and Harry Harootunian, “Japan’s Postwar and After, 1945–1989,” in From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan, 1945–1989, ed. Doryun Chong, Michio Hayashi, Kenji Kajiya, and Fumihiko Sumitomo (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 17–21. ↩

- Saitō Yoshishige, Tsuruoka Masao, Komai Tetsurō, and Oyamada Jirō, “Depicting ‘Things’ Not ‘Ideas’ (1954),” in Chong et al., From Postwar to Postmodern, 58–63. ↩

- Tōmatsu Shōmei, “A Young Photographer’s Statement: I Refute Mr. Natori (1960),” in Chong et al., From Postwar to Postmodern, 152. ↩

- Yamagishi Shoji in Szarkowski and Yamagishi, New Japanese Photography, 11–12. ↩

- Yoshihara Jirō in particular pursued concordances between East and West by way of a renewed japonisme among abstract painters such as Franz Kline, with whom he collaborated on an issue of the journal Bobukai (Ink beauty). See Ming Tiampo, Gutai: Decentering Modernism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 78–79. ↩

- Peter Yeoh, “The Sky in Flames: Photographs of Tōmatsu Shōmei,” Impressions 34 (2013): 96–107. VIVO formed in the wake of the 1957 Tokyo photography exhibition Eyes of Ten, seen as a rejoinder to the humanistic tendencies of curators such as Edward Steichen. ↩

- Darwin Marable, “Eikoh Hosoe: An Interview,” History of Photography 24, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 86. See also Chinghsin Wu, Parallel Modernism: Koga Harue and Avant-Garde Art in Modern Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019). ↩

- Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Black Male/White Male, with an introduction by Alex Hirst (London: Gay Men’s Press, 1988). ↩

- Alex Hirst, “Introduction,” in Fani-Kayode, Black Male/White Male, unpaginated. ↩

- See Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind E. Krauss, Formless: A User’s Guide (New York: Zone Books, 1997). ↩

- Chthonic refers to the underworld in various modes. As Bois and Krauss note, the insectoid (as a key motif of the chthonic) exemplifies one register of their account of informe. In the case of Hosoe, in one photograph from Man and Woman, the actual tentacles of an octopus appear like an offering, its suckers contorting in the blackened background, while the masklike upper third of a woman’s face looks outward, mere inches away. Of course, in the modern Japanese context in which Hosoe made this image, the sexual resonance of this composition would be clear: interspecies erotica featuring cephalopods was, in the nineteenth century and beyond, a recurrent tableau (e.g., in the visual culture of the “floating world” by, among others, Katsushika Hokusai). Such work has thrived as a distinct subgenre in the aftermath of censorship proximal to the American occupation (1945–52). ↩

- One scene from Man and Woman shows two figures seated and bending forward in the lower half of the frame, their heads not visible, the picture notable for its high gloss and deep shadows. This is an instance of Surrealist defamiliarization of the upper torso as well as a pose that Fani- Kayode appears to restage in his Maternal Milk (1988), in which a thin stream of fluid drips onto the subject’s folded back. ↩

- Especially in terms of class, with respect to the political and spiritual elitism to which he was heir back in Nigeria and the relative poverty in which he lived during his years of exile in England. ↩

- Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), 17. ↩

- See T. J. Demos, Return to the Postcolony: Specters of Colonialism in Contemporary Art (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013); and Hannah Feldman, From a Nation Torn: Decolonizing Art and Representation in France, 1945–1962 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014). ↩

- See, for example, “Kindai Shashin no mondai,” Camera 46 (October 1953): 65–73. ↩

- Quoted in Marable, “Eikoh Hosoe,” 87. ↩

- Dawn Ades, ed., Dada and Surrealism Reviewed (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978). ↩

- See Rosalind E. Krauss, Jane Livingston, and Dawn Ades, Amour Fou: Photography and Surrealism (New York: Cross River Press, 1985). The exhibition toured to London from July to September of that year. ↩

- Sandra Zalman, Consuming Surrealism in American Culture: Dissident Modernism (London: Ashgate, 2015), 143–67. ↩

- See Sophie Leclercq, “As Beautiful as the Fortuitous Meeting of an Aphrodisiac Jacket and a Yup’ik Mask, or Surrealist Primitivism by Analogy,” in Surrealism and Non-Western Art: A Family Resemblance (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2014), 21–40. This point is echoed in Elizabeth Cowling, “An Other Culture,” in Ades, Dada and Surrealism, 430–69. ↩

- On the internationalist ambitions of the Gutai group, see Tiampo, Gutai, 75–98. The transnational curatorial program launched during those early years of 1955–65 would have been broadly influential. ↩

- Rosalind Krauss argued that the latter resemble detached phalli in “Corpus Delecti,” October (Summer 1985): 31–72. An overview can also be found in reproductions of Documents in Dawn Ades and Simon Baker, eds., Undercover Surrealism: Georges Bataille and DOCUMENTS (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006). ↩

- Mignon Nixon, “Posing the Phallus,” October (Spring 2000: 98–127 ↩

- Yoshihara Jirō, “Gutai Art Manifesto” reproduction, originally published as “Gutai bijutsu sengen,” trans. Reiko Tomii, Geijutsu shincho 7, no. 12 (December 1956): 202. ↩

- Mark Sealy, “A Note from Outside on Rotimi Fani-Kayode,” in Rotimi Fani-Kayode (1955–1989), ed. Sealy, exh. cat. (Syracuse, NY: Light Work, 2015), unpaginated. This is a reproduction of an essay from 1995 that also appeared in a small catalog titled Communion. ↩

- Fani-Kayode, Black Male/White Male, 38. ↩

- Hosoe would reprise such a collaboration for 1969’s Kamaitachi, in which he and Hijikata Tatsumi collaborated with residents of a farming village to tell the story of a demon that haunted rice fields. Incidentally, the cover of the book features a slain woman in repose amid a field of flowers and leaves—a tableaux Fani-Kayode very nearly reproduced with a Black male sitter in the Communion color works of 1989. ↩

- From accompanying portfolio text in Arabella Plouviez, ed., Bodies of Experience: Stories about Living with HIV (London: Camerawork/The Photo Co-op, 1989), unpaginated. ↩

- The haunted house is a key component of the Freudian unheimlich (uncanny) and a leitmotif within much earlier Surrealist work and (later) elements of the horror genre that rely on the uncanny. See Jane Alison, The Surreal House (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010). ↩

- See, for example, Jean Dykstra, “Ba-Ra-Kei: Ordeal by Roses,” Art on Paper 7, no. 4 (January– February 2003): 89. ↩

- This is admittedly a passing reference to a vast body of literature but alludes to a mode of color photography of, for example, Gregory Crewdson or Philip-Lorca diCorcia. The phrase “directorial mode” anticipates the Pictures generation and was published concurrently with Fani-Kayode’s arrival in the United States in the April 1976 issue of Artforum International. ↩

- Eikoh Hosoe, quoted in Chehada, “Eikoh Hosoe on Barakei.” ↩

- Here exposed onto an exaggerated eye, perhaps a reference to the organ’s grotesque association in the earlier work of, for example, Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali, or Max Ernst. ↩

- Marable, “Eikoh Hosoe,” 87. ↩

- This is beyond the immediate scope of my argument, but suffice it to note that there are many layers of resonances with this work: hand-tinting as means of overriding mass reproduction; the invocation of a Yoruban plague deity; the iconology of disease; the hagiography of Saints Roch and Sebastian, and so on. ↩

- On the haptic and affective in recent photography, see Elspeth H. Brown and Thy Puy, “Introduction,” in Feeling Photography, ed. Brown and Puy (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 1–25, esp. 8–17. ↩

- Ignacio Adriasola, “Melancholy Sites: The Affective Politics of Marginality in Post-Anpo Japan (1960–1970)” (PhD diss., Duke University, 2011), 139, quoted in Bourland, Bloodflowers, 240. ↩

- Mishima Yukio, quoted in “School of the Flesh: Erotic Pictures of Yukio Mishima—In Pictures,” Guardian, November 3, 2016, unpaginated. ↩

- It would be reductive to overly correlate the fallout of World War II with the heterogeneous Japanese avant-garde of the era, but documenting that very “fallout” was a lifelong project for Hosoe. ↩

- Kerry Brougher, “Radiation Made Visible,” in Damage Control: Art and Destruction Since 1950, ed. Brougher, Russell Ferguson, and Dario Gamboni (New York: DelMonico Books, 2013), 12–103. ↩

- For a lengthy discussion of Mishima’s childhood encounters with death and its lingering impact, see Robert Jay Lifton, The Broken Connection: On Death and the Continuity of Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979), 262–80. ↩

- See Ignacio Adriasola, “Modernity and its Doubles: Uncanny Spaces of Postwar Japan,” October 151 (Winter 2015): 108–27. ↩

- J. Keith Vincent, Two-Timing Modernity: Homosocial Narrative in Modern Japanese Fiction (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 175–98. ↩

- One segment of “Traces of Ecstasy” speaks to the legacy of Nazism specifically and the conservative forces in England working to suppress so-called difference in its myriad forms. ↩

- There is much to be said about the final years of Mishima’s life and political program. Beyond Ignacio Adriasola’s PhD dissertation cited above, see Kara Reilly, “Mishima’s Balcony Performance: Hypermasculinity, Masochism, and Reactionary Vanguardism,” in Vanguard Performance Beyond Left and Right, ed. Kimberly Jannarone (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015), 94–121. ↩

- Sealy, “Note from Outside on Rotimi Fani-Kayode,” unpaginated. ↩

- See, for example, the Nippon (1967) and Oh Shinjuku! (1969) series, both partially on display at the 1974 MoMA exhibition. ↩

- Betty Jean Lifton and Eikoh Hosoe, A Place Called Hiroshima (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1985), 7. This volume updates an earlier iteration of the Hosoe and Lifton collaboration, Return to Hiroshima (New York: Atheneum, 1970). ↩

- Consider another spectral trace: the indexing of vaporized bodies as shadows on city walls, in the aftermath of Hiroshima. ↩

- Mishima produced his own theatrical projects in the form of the Noh tradition. See Miryam Sas, “Hands, Lines, Acts: Butoh and Surrealism,” Qui Parle 13, no. 2 (Spring–Summer 2003): 20. ↩

- Eikoh Hosoe, quoted in Yseult Chehada, “Eikoh Hosoe on Man and Woman,” video recording, Aperture Foundation, May 5, 2010; see also Carole Naggar, “The Costume of the Soul: Eisoh Hokoe’s Photographs of Butoh Dancer Kazuo Ohno,” Aperture 165 (Winter 2001): 54–64. ↩

- Derek Jarman, quoted in Derek (2008), dir. Isaac Julien. ↩

- This is widely discussed in the work of, for example, Abigail Solomon-Godeau and Douglas Crimp. See the latter’s “The Photographic Activity of Postmodernism,” October 15 (Winter 1980): 91–101. ↩

- Ming Tiampo, “Originality, Universality, and Other Modernist Myths,” in Art and Globalization, ed. James Elkins, Zhivka Valiavicharska, and Alice Kim (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2010), 169. ↩