Peripatetic Pandemic Soundtrack: Singapore/Chicago, 2020–21, sound, 8:17 min. (artwork © Christa Donner)

This project includes an audio component of ambient sounds collected during walks during the pandemic periods discussed in the conversation below—first in Singapore, then transitioning into late winter in Chicago. For an immersive experience, listen with headphones as you follow the numbered dialogue. For those reading on a mobile phone, we suggest viewing in landscape mode.

Let’s go on a walk, maybe a tangent, together.

What follows is a conversational excursion held between Chicago and Singapore that began on March 27, 2021—at night in one time zone, morning in the other. One year into the COVID-19 pandemic we meander through perception, behavior, and thoughts with embodied senses activating during what some have called the “anthropause.” This walk takes the form of a conversational “drift,” kept alive through varied rhythms of synchronous editing over the past year. In pairs we observed things often overlooked in our immediate surroundings, which expanded into dislocated layers of dialogue and geography.

This conversation started through creative projects in Singapore: artist James Jack, director of the Yale-National University of Singapore (Yale-NUS) artist-in-residence program, hosted Christa Donner and Andrew S. Yang just as the pandemic was starting in 2020 (although none of us knew it yet). In the midst of Singapore’s “Circuit Breaker” lockdown, curator Karin Oen worked with cocurator Magdalena Magiera and other colleagues at Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore (NTU CCA) to plan for Free Jazz III. Sound. Walks, a socially distanced sound-based exhibition that opened in early 2021. They invited Donner and Yang who, responding to the isolation of lockdown, created a series of experiential sound walks inviting citygoers to tune in and reconnect with the natural world.

Our conversations rotated between Chicago at night and Singapore in the daytime; editing took place in the months after the walk. As we returned to the transcript of the conversation over and over, it began to expand and contract in unpredictable areas; come alive and grow while we reflected on travel, tides, teaching, and more, finding creative resonances together. The black/white text is drawn from our walking conversation, while gray is a metatext that weaves in commentary that arose in the process of dialogic editing. In this way, the conversation occurs in multiple presents—an ambulatory space of creative possibilities and dislocations that arise from constant shifts in experience and expectation: micro, macro, in vivo, in vitro, here and there, all at once.

March 27, 2021 Singapore 21:04

1. James Jack: Good morning!

3. Karin Oen: There is a bright, almost full moon. And it’s hot and sticky, but not especially hot and sticky by Singapore standards. We are walking near the Istana which is heavily fortified, but aesthetically pleasing.

5. Oen: I am hearing some sort of security imitation bird.

Jack: Is it? Sounds like a bird or a frog. Is it fake?

Shasei is a concept in Japanese painting that literally means “copy” of “life.” What are we copying now from life while in these moments together?

7. Oen: For me your sound walk pieces have been really helpful.

It’s been interesting to think about how these soundscapes all simultaneously exist in different locations.

Even if people aren’t personally affected by COVID, there is major global anxiety happening that I think you picked up on—it was a bit of a running theme in the Listening Through the Landscape pieces featured in Free Jazz III. They all had a therapeutic aspect related to connecting to our senses and environments. The anxiety, it’s just the air that we breathe right now and anything that doesn’t really address how people are under a very real kind of stress is missing the mark.

Chicago 8:04

2. Andrew Yang: Good evening, nice to hear your voices. What is the atmosphere like on your side of the planet?

4. Yang: It’s completely overcast here, about forty-five degrees Fahrenheit—officially “chilly.”

and now a frigid fifteen degrees, and the earliest sunset of the whole year as I proof this text . . .

Christa Donner: We’re wearing coats.

(goose feather down, I think)

6. Yang: Maybe fake can be just as good for some purposes? The mimesis of the thesis.

8. Yang: Yes, quite literally it is the air that we breathe! Metaphors and viruses, both airborne contagions.

Donner: With everyone stuck at home because of the pandemic . . . short walks outside became such an important activity, often alone or with someone far away on the phone. Suddenly the smartphone felt like such an important interface—a way to transform that familiar outing into something else. To reconnect to the rest of our ecosystem, something many of us forget how to do when we’re living in the city.

We just walked by a big dead tree that’s being chopped up.

11. Jack: What do you see or hear or smell while walking there?

13. Oen: We’re in this little part of Singapore that’s adjacent to the president’s house. It’s one of the few places without a lot of high-rise towers because of security protocols.

Now it’s October, I’ve moved to a new neighborhood with seemingly endless blocks of high-rise towers, where it’s harder to get a glimpse of the moon, and somehow feels hotter all the time.

15. Jack: That’s funny too, you mentioned the smell of your mask, right? The cut tree here that we came across has an earthy wet scent—almost like a Cabernet—that I’m noticing even through my mask now.

17. Jack: Nice!

19. Jack: What you’re talking about with these students reminds me of your sound walk Water, when narrator and student Alexis Chen says, “If it’s not raining right now, it’s a sunny day, let me change that.” Changes in the weather occur alongside your virtual environment shifting quickly based on the people you’re with or the things that are happening in your inner weather.

I have been thinking about this through a guide to loving water, reflecting on the abundant resources that keep us alive now and searching for collective ways of respectfully sharing knowledge on how to care for them. In the classroom, studio, and outdoors we are working to empower others to navigate multisensorial climates in creative and responsible ways.

21. Jack: While on the way to the studio this morning to meet online and continue editing this conversation, I noticed the high tide. Now it is November and haven’t left this island for twenty-two months. It just stopped raining and I am now feeling drained, another humid cloud is on its way toward us now while revisiting this ongoing conversation.

Oen: “Drained”—that’s how we’re all feeling, almost two years into this pandemic when we’re still juggling the teaching and family and other needs that don’t let up, tech challenges, long-term instability in our various institutions and the multiple countries and cities that we are individually and collectively tied to.

23. Jack: How can we work with, beyond, or around the resonances of the two locations we are in now?

We just encountered an orange fence that prevents us from walking up to the cut-up tree.

Oen: People aren’t going to go if there’s a fence, even a flimsy one—it really restricts how you can use a space.

25. Oen: There are all these places to check in with the “Trace Together” location trackers out here in the park. It’s not just about logging your location when you enter a building, but also translating that experience outdoors . . . checking in at a tree.

27. Oen: But it’s also simultaneously this sense of tracking I had when I was a teenager with a beeper. There was the freedom that came with having a beeper because my parents could contact me if they needed me, it gave me the license to go and do stuff that I otherwise would be restricted from doing in exchange for submitting to constant surveillance . . .

Jack: As Woon Tien Wei reminded us recently, COVID has made what is already there more visible, I have a heightened awareness of security cameras monitoring indoors and out. There is a sense of social responsibility for the elders in the community here.

29. Oen: Whereas here in Singapore, many are happy to sign up for more surveillance because that somehow gives you more freedom. It’s like the more you can document that you’re vaccinated or otherwise risk-free then the more freedom you are allowed.

Jack: COVID gives an additional justification for territorialization of urban space, including steel beams for asserting expanded boundaries for land, like the ones being noisily inserted into the sea now pulsing the cement in this building. Now, as we sit in the studio together overlooking Pasir Panjang container port on a Sunday, I empathize with the small boats moving about in search of fish, but perhaps more importantly it is a respite from the urban rush, which I am realizing might be one of our primary motives for this walk story itself.

We’re now standing in front of the yellow gate with an arch on top of a maroon “I” of the Sikh Temple Sri Guru Singh Sabha, all cement maybe.

Oen: It’s kind of reminiscent of 1980s geometric postmodern, with a Michael Graves-like thing going on. The temple itself was established in 1918, but do you think this building is from 1988? It’s funny because it being a sacred space, there are certain restrictions that are always in place, so it has a big sign saying that alcohol, meat, and tobacco are strictly prohibited on the temple premises, and then you just overlay that with a lot of newer COVID restrictions that are also in place.

31. Jack: Let’s all close our eyes, it really changes sense perception.

33. Jack: This is an interesting curve in the walk story, returning to our bodies and noticing humidity mixed with sweat, a pigeon peeking in on us from the industrial window ledge, to think expansively in dialogue with natural and human disasters, mosquito fogging the neighborhood, and an announcement made yesterday about malaria vaccines.

We spoke about cohabitation with art historian Michelle Lim while you were in Singapore, and spirits telling us when we are doing something right or wrong . . . Any thoughts on this after returning to Chicago?

35. Jack: What communities have you felt connected to, and which ones have you felt separated from during the past year?

37. Oen: Or they’re on the other side of the world!

39. Oen: I guess for me I really have enjoyed the kind of equalizing effect of not having the option to travel and not feeling like there is this obligation to be globetrotting or contributing to an enormous carbon footprint that is the art world and which I don’t particularly approve of but was definitely party to before. And I think the shift to trying to bring a community online and really meaningfully rethinking what can happen more easily or better in an online format. That part has been very refreshing.

Just received the link to a journal article that I wrote in response to my participation in Gallery Weekend Kuala Lumpur 2019, a very different moment when travel was actively encouraged as a mode of community building.

I feel like time passed rapidly before. I feel like every year of my life I’ve said, “I can’t believe the year is half over.” But now we’ve been spending more quality time with the people who are around. And that’s something I am very grateful for because previously, and it’s obviously always an option, it was harder for me to make the choice to just stay in one place.

41. Oen: Oh, my god, yes.

Jack: Totally. It’s really made me think carefully about who I talk to and why I am talking to them. Some people we stop talking to since we’re physically not meeting each other in the foreseeable future.

And other people we choose to spend expansive time together even with unstable internet, the tensions of quarrelling kids, restricted interactions, and dislocated connections for the creative sustenance we provide each other in making kin.

Where there is a herd instinct relations grow, otherwise disperse instinct kicks in.

This morning my son woke up and wanted to go kayaking. We pay a lot of attention to tides, so I said, “Yes, we can go! It’s high tide right about now.” (Yesterday around this time I saw the tide was high.) Before, I would have known something like what times the direct flights to Narita or Haneda depart and when the taxis are cheapest to Changi airport or something. That would be part of my everyday consciousness.

During the lockdown I focused on microphenomena of our immediate ecological community and this sensitivity continues.

Which are not so micro when considering carbon use when flights are still only a fraction of what they were two years ago in and out of Singapore. The prolonged haze has not returned and a cycling boom continues as ridership grows.

43. Jack: Fewer trips, stay longer—we only go places we will stay for a significant amount of time—one of the reasons why residencies such as the one you participated in have been able to continue during the peak of the pandemic. In some ways being in residence is a model that fits with COVID much more than other art models. Still going places while staying at home, less geographic multitasking.

45. Jack: I have been reconnecting with artists, students, and people I know here that are kind of very focused on local issues. And a lot of that is about decolonization. I have been thinking a lot more about how to decolonize thinking. And about writing and art making in a particular Singaporean hierarchical system that was built upon colonial models—how do we undo those kinds of top-down power dynamics today in our art, teaching, and lives?

47. Oen: It’s true. I feel that the intimacy and connectedness within the community here has been amplified by the common constraints and challenges of the pandemic. For many artists I think the restrictions on travel have created more reasons to connect locally and reconsider what it means to be based here in Singapore as opposed to being based somewhere that is a convenient hub. As James was saying, it’s also a chance to reflect critically about how we teach and work, and what needs to be rethought.

49. Oen: It was really nice to have a conversation while meandering.

Jack: Walking in moments up to and including ongoing stories now.

10. Yang: That’s so weird, we also just walked by a big tree that was chopped up here that must have been just cut down—transplanetary synchronicity.

12. Yang: That’s a good question, my glasses are always fogged up . . . We are walking through a residential area with lots of these late-1800s, early 1900s houses in a neighborhood near where we live—really large, quite expensive houses. But it’s tree-lined and grassy, we hear the birds singing. And I just heard a jet fly overhead.

But now I wonder—are they also “security imitation birds”?

Donner: It’s early spring in Chicago. The first flowers are coming in, which is really nice to see after a long and very dark winter.

A winter that is just starting now again . . .

14. Yang: Like Singapore, Chicago is also a skyscraper city, but in this part where we’re walking right now, very few buildings are higher than three stories. And then once you get to the lake it all gets tall again because people want an expansive view. In terms of your question, James, about smell—I just pulled my mask down to smell the air and I really smell . . . fried chicken! There’s a commercial street about a block away. It’s weird because it’s a very picturesque neighborhood where they shoot a lot of movies and TV shows—it’s an urban residential picturesque that looks suburban. But then the smell of fried food in the air reminds you that you’re in the city.

16. Yang: The bouquet of the fallen tree.

18. Yang: I hadn’t thought about it that way, that there are multiple ways in which COVID has created a loss of smell. For some people who get infected it is a symptom, but also for everyone else who is always just masked up, smells simply get blocked.

Donner: I’m teaching a studio research class on the five senses and I had my students do a smell mapping exercise. I usually take them to an open-air market, but I couldn’t do that this year because of COVID. So I said, “Okay, we can explore the area around the college, downtown.” There was so little to map because they’re noticing their own breath inside their masks mainly, and then whatever gets through is just stuff you probably shouldn’t be smelling. One map had Xs through all the restaurants that were closed, with moments of urine or cigarette smoke.

20. Donner: During the pandemic we’re mostly indoors or online instead of having physical experiences around the city. So, we’re making performative sensory scores for people to experience at home. I have a student from Singapore, actually, who’s making a really lovely three-course score involving the smell of thunderstorms and trees.

22. Donner: We talked to some friends in Singapore about the sound walks and they said, “We were listening to the The Living Machine track, which is filled with the sounds of local cicadas, and when we took our headphones off it sounded exactly the same!” [laughter] Because those insects are singing all the time, everywhere. Whereas here it’s such a different soundscape. We have very different cicadas, and they’re only around for a short time—mostly in August and September. They signal the change of seasons.

Yang: You know, I think the seventeen-year cicadas are coming soon.

24. Donner: Our daughter has just found a plastic chain—sort of a divider. She’s swinging it around like a jump rope.

Yang: It’s this piece of chain that’s diagonally coming out between someone’s house and lawn. I think because they don’t want people to cut the corner and walk on their grass.

26. Yang: It is interesting, as you’re talking about it, it sounds like sort of imprisonment. The tracker makes me think you’ve got one of those electronic ankle cuffs on that track and monitor you to see if you’re breaking your house arrest or parole.

Donner: I’ve started using QR codes to disseminate more sound work now . . . it means you can embed art (and lots of other things) in any park or yard or shared space . . . with or without permission.

28. Yang: Chicago’s downtown is one of the most heavily surveilled cities in terms of cameras. But in terms of COVID, it’s laissez-faire in many ways, and then inconsistently strict in others. We were not supposed to go to the parks and kids are not allowed on playground equipment but you can crowd into a bar. The city’s gone through cycles of inconsistent restrictions. So, we’re left to our own devices.

30. Donner: The way you were describing, I just closed my eyes for that minute, and was imagining it clearly, even though I’m standing in the sun in chilly Chicago, with little birds singing nearby. I was there for a minute. I was there in the dark nighttime, looking at the Sikh temple.

32. Donner: We’re very suggestible animals. Language combined with sensory attention can transport us. In thinking about how we might engage others in conversations about climate change, how do we get people back into their bodies? Maybe moving beyond the visual is the way to do that.

34. Donner: When I think about people’s relationship to the landscape here, it is very different from when we were in Singapore. To hear people there mention the spirits of the forest who make sure kids don’t get hurt and how you have to be respectful of that tree or else something bad will happen . . . it reminds us that trees and insects are beings, not “things.” Those relationships are important—we are a part of each other’s communities. That’s something we really wanted to bring to the sound walks, in a way that could be felt anywhere.

36. Donner: At the beginning of 2021, I was feeling a lot of dread about “how am I going to build a sense of community online?” It has been really interesting to go from “Oh, this is so depressing, we have all these limitations,” to it becoming kind of a creative prompt instead of a roadblock. Also, there are so many artist talks and events I’ve been able to attend that I wouldn’t have otherwise as a parent because they’re happening at eight o’clock at night.

38. Donner: Zoom can be exhausting, but it has made a lot of events so much more accessible for people caring for kids or elders, people with disabilities, and international audiences. That’s something I hope we can continue on some level: the ability for people to participate in a range of ways, in-person and remotely.

Now that I’ve returned to teaching mostly in-person, I find students asking to join remotely because they woke up late or they’re visiting friends in another city. It can really compromise the class to be constantly checking that everyone can hear/see each other virtually and in-person, sharing media for two spaces at once. You really need a separate virtual facilitator to make a hybrid event run smoothly.

Yang: That points out how new online options have perhaps created forms of hybridity that have become downright unuseful or overly complicated. It seems to be reproducing the “split attention” problem of using screens while being embodied. Is this the “Metaverse 1.0″? If so, maybe I am happy to leave it be . . .

It’s tough, because when you have young children, your sense of time is changing every year as their sense of time and age also change. But it’s almost exactly the first anniversary of Singapore’s “Circuit Breaker” lockdown and the passage of time has felt different to me again. Do you feel like your sense of the passage of time has changed between the lockdown and not traveling as much?

40. Donner: That is something I think about so much. I really enjoy social engagement, but not this pressure to be constantly out there. In a weird way, it’s been a bit of a relief.

I wonder if you still feel this way now that the plans we do make get thwarted as new waves of the pandemic ebb and flow?

42. Yang: But how are you preparing for the temptation or the pressure to go back to that way of living?

“To go back to that way of living . . . ” It is funny to think about this idea now—looking at this text one last time finds us all in the midst of the latest variant, the Omicron wave. Some of us are moving a lot again, as the spread of Omicron attests to, while many more are still in place, sometimes stuck, maybe now more by choice. Either way, in hindsight the idea of “going back” seems impossible, for worse but maybe too for better.

44. Yang: It’s another way to interpret that phrase “when going means staying.” For us that was staying because of the conditions of the pandemic—restrictions on international travel, the bad shape the US was in the early days, but also wanting to stay in Singapore and do whatever we could to continue making art. But it took on a whole other kind of quality. You’re saying that “when going means staying” is about committing for a duration—being in that place and not necessarily all the other places along the way in the itinerary.

46. Donner: We’ve gotten to know our neighborhoods differently, first in Singapore and now here. We go for so many more walks than we ever used to, in all kinds of weather.

Yang: It is like what you were saying, James, about engaging more with the local community instead of more with the global community. To some extent people like to be in a city like Chicago or Singapore because you can be everywhere else—because it is this sort of global hub. But then you’re like, “No, I am here because I am here with intention.”

48. Yang: We’ve been talking about the idea of how the pandemic in Singapore affected your impression of the island, both geographically and conceptually. Rather than the sense of the island as an isolated place, you’re both thinking of it as more of this protected space of the possibility of community—that’s about being inclusive as opposed to isolated.

Donner: We came to Singapore with a sincere interest in the country, but everybody talked about what a hub it is to get to everywhere else. Because of the pandemic that just wasn’t part of our experience. Instead, we got to know people and hidden areas we might not have found if we had been constantly flying to other places. COVID has been terrible. But it’s also been such an important time of reassessment. As you’ve both said, it made us think differently about where we center ourselves and who and what’s important.

The authors would like to thank Jeannette Ickovics for her vision, Alexis Chen for her role in this artistic research, Tom White for program support as well as Yi Qian Chan and Ahmed Fedi Lassoued for their assistance transcribing the recording of this conversational walk. We would also like to acknowledge the support from the Yale-NUS College artist-in-residence program, Tan Chin Tuan Foundation, and NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore that has made the artworks and research here possible.

Christa Donner investigates the human/animal body and its metaphors through a variety of media, from large-scale drawing to guided sensory walks. Recent work includes projects for Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore (NTU CCA), Singapore, the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, and Chiaki Kamikawa Contemporary Art in Cyprus.

James Jack engages layered histories of place to achieve positive change. His artworks have been exhibited at Setouchi Triennial, Honolulu Museum of Art, Donkey Mill Art Center, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Art, Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore (NTU CCA), Singapore. He is currently associate professor of Intermedia Art, Waseda University in Tokyo.

Karin G. Oen is a curator and art historian who investigates transdisciplinary and transhistorical practices in global modern and contemporary art. She is senior lecturer and head of art history at the School of Humanities, Nanyang Technological University and was recently deputy director, of curatorial programs, at Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art (NTU CCA), Singapore.

Andrew S. Yang works across the visual arts and natural sciences. He has exhibited from Oklahoma to Yokohama, including in the 14th Istanbul Biennial, at MCA Chicago, Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, and Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore (NTU CCA), Singapore. He is a professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

All images untitled and produced by the authors, unless otherwise noted below.

Fig. 1: Christa Donner and Andrew S. Yang, Listening Through the Landscape, 2020 (detail), mixed media (artwork © Christa Donner and Andrew S. Yang)

Fig. 2: James Jack, Mid-autumn Moon Festival in Changi, digital image, 2021 (artwork © James Jack)

Fig. 3: Christa Donner and Andrew S. Yang, Walk in Andersonville Chicago, digital image, 2021 (artwork © Christa Donner and Andrew S. Yang)

Fig. 4: Karin G. Oen, Untitled, digital image, 2021 (artwork © Karin G. Oen)

Fig. 5: James Jack, Walk Story Singapore, digital image, 2021 (artwork © James Jack)

Fig. 6: Christa Donner and Andrew S. Yang, Walk story Chicago, digital image, 2021 (artwork © Christa Donner and Andrew S. Yang)

Fig. 7: Andrew S. Yang, Untitled, digital image, 2021 (artwork © Andrew S. Yang)

Fig. 8: James Jack. Experiencing Sound Walk in Clementi, Singapore, digital image, 2021 (artwork © James Jack)

Fig. 9: James Jack, Mid-autumn Moon in Changi, digital image, 2021 (artwork © James Jack)

Fig. 10: Karin G. Oen, Night Walking around Mt. Sophia, digital image, 2021 (artwork © Karin G. Oen)

Fig. 11: Andrew S. Yang, Walking in Chicago, digital image, 2021 (artwork © Andrew S. Yang)

Fig. 12: James Jack, Walking in Clementi Park, digital image, 2021 (artwork © James Jack)

Fig. 13: Andrew S. Yang, Chicago Security, digital image, 2020 (artwork © Andrew S. Yang)

Fig. 14: Karin G. Oen, Walk story online editing session, digital image, 2021 (artwork © Karin G. Oen)

Fig. 15: Karin G. Oen, Walking around Mt. Sophia, digital image, 2021 (artwork © Karin G. Oen)

Fig. 16: Christa Donner, City in a Garden (installation view), watercolor and ink on cut paper, 2020 (artwork © Christa Donner; photograph by Tom White)

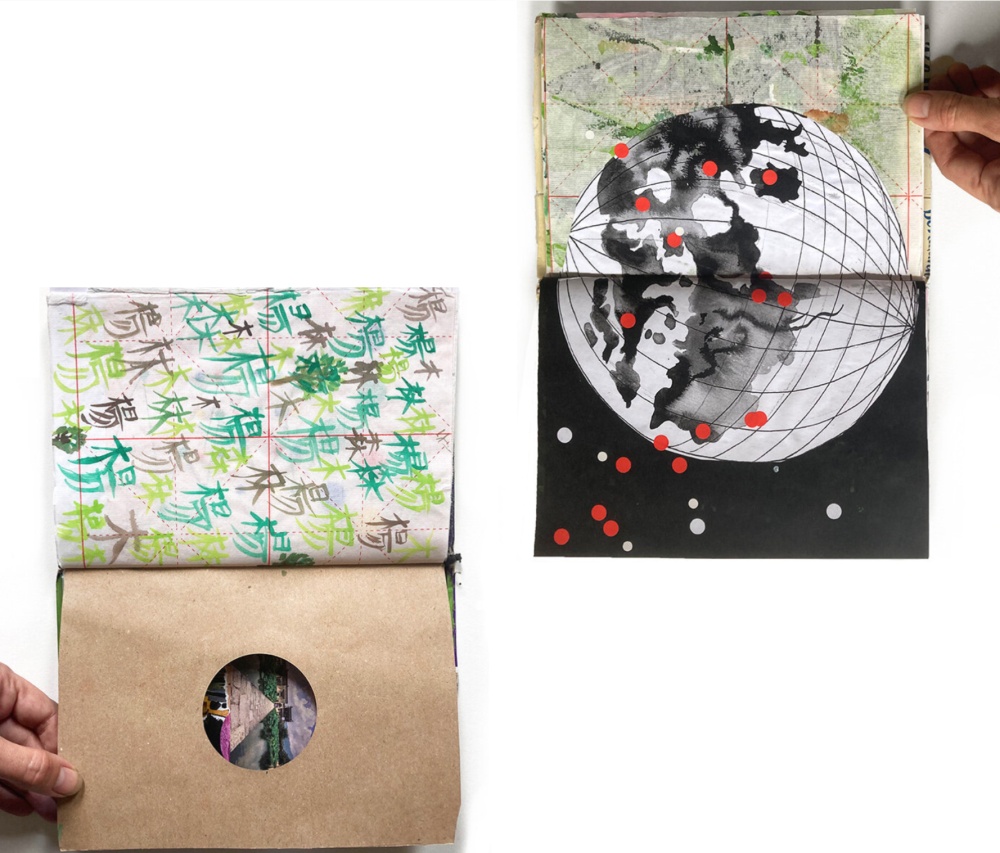

Fig. 17: Christa Donner and Andrew S. Yang, Circuit Breaker Sketchbooks (detail), handmade books with mixed media, 2020 (artwork © Christa Donner and Andrew S. Yang)

Fig. 18: Christa Donner and Andrew S. Yang, Untitled, digital image, 2021 (artwork © Christa Donner and Andrew S. Yang)

Fig. 19: James Jack, High Tide in Pandan Estuary, Singapore, digital image, 2022 (artwork © James Jack)

Fig. 20: James Jack, Experiencing Sound Walks in Clementi, Singapore, digital image, 2021 (artwork © James Jack)