Teaching for a Future-Oriented Art History

What are the limits and boundaries of our classrooms? Where and how should our syllabi begin and end? These questions have become increasingly weighty since 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic converged with the longer-standing pandemic of systemic injustice in the US to amply demonstrate that our classrooms are not protected from the upheavals of the world around us. In this series of essays on pedagogy, three art historians (Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi, Yael Rice, and Nancy Um) reflect on classroom experiments—all conducted in 2020, the first year of the pandemic—to expand the purview of the classroom, by inserting into their teaching issues such as ethics, well-being, new research practices, innovations in technology, collaboration, and museum- and collection-based work as fundamental concerns of the discipline. As a group, these three essays, which will appear in succession, consider what the future of the art history classroom might look like, as we face the ever-changing challenges of the twenty-first century.

In a 2020 article in the Canadian Historical Review, Ian Milligan declared, “We are all digital now.”1 With this bold statement, he was not pointing to the broad adoption of computational methods across his own discipline of history. To the contrary, he was speaking about the practicalities around the way historians work, which, even before the global lockdowns instigated by the COVID-19 pandemic, had ceased to be oriented solely around extended consultations with original materials in archives or hours scrolling through microfilm. Now, most historians drop into the archives for a few days with their digital cameras or smartphones and snap thousands of photographs before returning home to sift through these documents as digital files on their computers. He sketches a vision of today’s historian awash in personally produced (but also poorly shot and uncatalogued) digitized materials, whose research strategies increasingly hinge upon discoverability and search functions rather than perusal, and upon digital accessibility rather than archival chance. To be clear, Milligan’s declaration was by no means a lament. In fact, he underscores how these shifts in access and digital photography have opened the doors to research for those who do not have the luxury or resources to devote months to archival study, which often needs to occur far from home. His goal was simply to ask historians to take stock of these changes in scholarly habit and their salient impact upon historical methodology beyond mere procedural concerns, with a focus on the growing spatial and temporal disconnection between the collection of study materials and their analysis, a rupture that will surely have effects on historical writing into the future.

Like our counterparts in history, art historians have also shifted our research practices in libraries and archives in the ways that Milligan describes, but more significantly in regard to the vast world of digitized museum and library collections. These repositories, which swell progressively and exponentially in scale and scope, provide extraordinary access to objects, especially those that are rarely displayed to the public. Although the quality of the offerings varies considerably and we still tend to place a premium on the in-person encounter, we must acknowledge that these resources can offer a visual experience that exceeds certain capacities of direct observation.2 Some collections present high resolution and multidimensional visual documentation, including the unseen backs of canvases with their stretchers laid bare, the interiors of cabinets with their doors and drawers splayed open, manuscript pages that can be virtually unbound for side-by-side comparisons that would be impossible while perusing the actual book, and the potential to manipulate color, contrast, and brightness in order to home in on details that would otherwise be imperceptible to the human eye. And like historians, art historians have not thought reflexively about the impact of these modal changes on the interpretational work of art history, even while we welcome the appearance of each newly digitized collection. Yet, for most of us, the time that we spend planted in front of our screens, clicking, scrolling, and pinching, has come to exceed that which we devote to poring over objects in museum galleries and library reading rooms. Of course, this experience is also quite distinct, both visually and haptically, from the consultation of printed photographs or slides, whether on a light table or projected.3

Following Milligan, we should not lament the losses in visual and material perception entailed by digital access or unconditionally celebrate the gains that they may yield, as much as we need to acknowledge their ramifications and consider the fundamental question of how art historians are to interact with these copious digital or digitized materials that we deal with on a daily basis. By doing so, we will inevitably return to Johanna Drucker’s discussion about the inception (already fully effectuated) of a “digitized art history,” while also being inspired to reconsider our standard understanding of what constitutes art historical method, which is generally circumscribed as a set of intellectual concerns rather than physical or even mechanical maneuvers.4

Most art historians interact with digital visual assets in ways that are more practical than studied, storing images in dedicated folders on their own hard drives and executing the functional options offered by their default viewing software, without seeking any engaged, purposeful, or directed guidance about how to treat, work with, document, describe, manipulate, or interpret these ubiquitous research materials.5 Moreover, the metadata is usually disassociated from these jpegs, tiffs, pngs, and pdfs. Even when they are linked, they are generally considered to be supplemental, namely as the fodder for illustration captions, rather than as substantive sources in their own right with their own histories and for which distinctive research methods may be marshalled. Yet, new storage, viewing, and display platforms have become available to help us manage our stuffed hard drives, such as the ARt Image Exploration Space (ARIES), a collaboration between the Frick Art Reference Library’s Digital Art History Lab (DAHL) and experts in the Visualization Imaging and Data Analytics (VIDA) Research Center at the NYU Tandon School of Engineering, or Tropy, the research image management system offered by the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. For instance, Tropy allows the researcher to organize, tag, and annotate images according to accepted metadata standards, while also joining them to user-generated research notes and findings. But such technologies are not aimed at stimulating critical reflection about how to work with these images. Rather, they are oriented around workflow solutions, and ones that generally assume that each scholar will be the steward of their own personal collection. It is also clear that such technologies have not yet received wide adoption across the field.6

In Fall 2020, I had the opportunity to teach a small graduate seminar called “Art/History in the Digital Age,” at Binghamton University. This course was premised on taking into account the transformative effects of this changing research landscape, with the assertion that art historians of the next generation need to be aware of the protocols, structures, possibilities, and constraints that undergird the digital environments that we all work in. The timing was relevant as the COVID-19 pandemic had starkly delimited opportunities for archival research, museum visits, or site-based fieldwork, thereby rendering these longstanding transformations in art historical scholarly habit undeniably evident, while also accelerating them considerably. In this way, the pandemic has provided privileged globetrotting researchers with a new understanding of their own considerable advantages, exemplified by their relatively unfettered access to research materials. By extension, one hopes that these changed circumstances will inspire a broader perspective on the ever-present barriers that hinder research for those who face mobility challenges, those who do not hold prestige passports, those who lack access to research and travel funds, and those who work in parts of the world that are war-torn, politically unstable, or generally closed to scholars.7 Indeed, in 2020, we all went digital, as Milligan suggested, namely because we had very little choice in the matter, a shift that resulted in differential effects for scholars around the globe. Some felt encumbered by sudden restrictions on travel and constrained access to collections, while others discovered the possibilities offered by a widened community of international researchers who were willing to engage in extended online interactions, even if they involved awkward time zone conversions and perennial connectivity issues.

The purview of the Fall 2020 course entailed delving into the institutional histories of museums, libraries, and archives in order to think deeply about the nature of repositories, both physical and digital, while also investigating the relationships between the two and the question of access. Along the way we considered the protocols and politics of digitization, undergirded by a sustained discussion about the production of metadata and the place of authority files and controlled vocabularies in the language of art historical research. We endeavored to understand the scope of the information systems that we rely upon so heavily, highlighting the drive toward interoperability and the possibilities offered by linked open data. Following Harald Klinke’s invocation, we asked simply, “What is a digital image?”8 And, by examining the functional and interpretive avenues offered by International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) protocols and computer vision, we attempted to imagine its potential futures. These questions entailed delving deeply into the origin and aims of various mass digitization and aggregation projects (such as the Google Arts and Culture initiative), which students were familiar with as portals to visual materials online.9 But at the same time, they had rarely conceived of these digital collections in their own right or queried their scope, shape, history, or rationale. As a result, they came to see an institution such as the Williams College Museum of Art, with its open access metadata and images and interactive Collections Explorer, in a very different light than those that have not yet offered such access and those that do not provide any avenues for dedicated engagement with their digitized collections.10

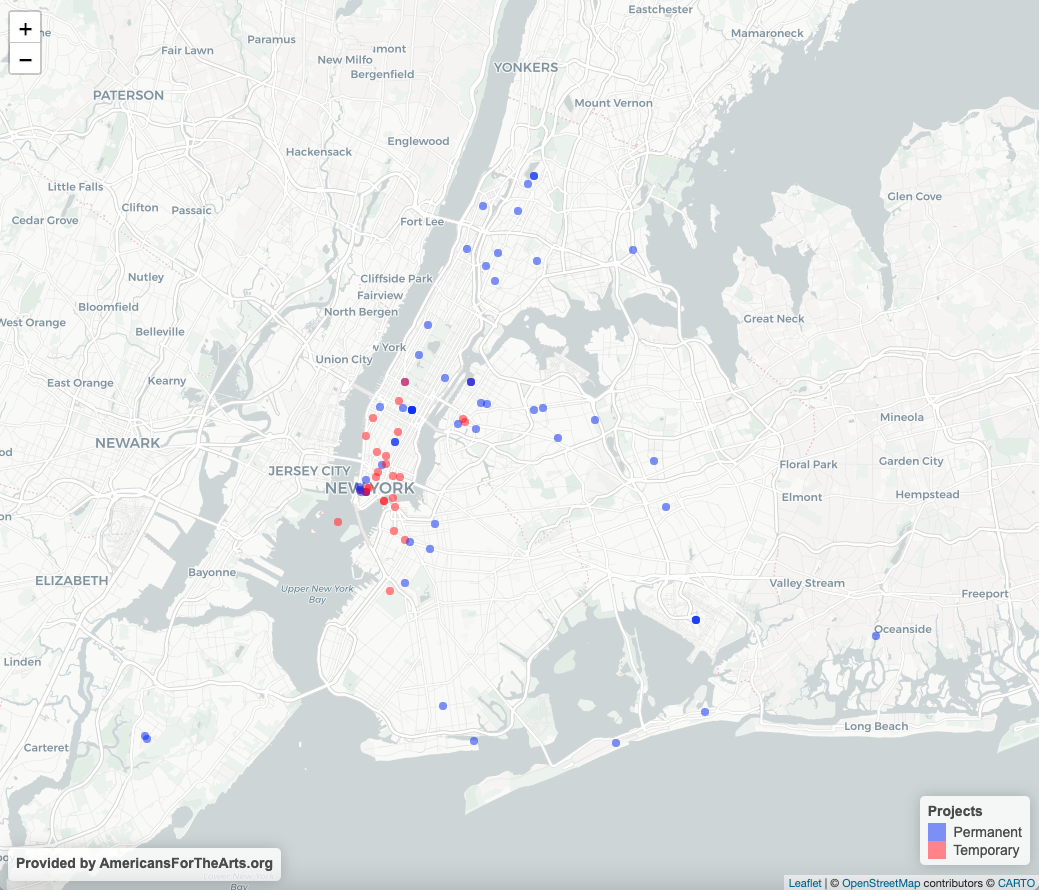

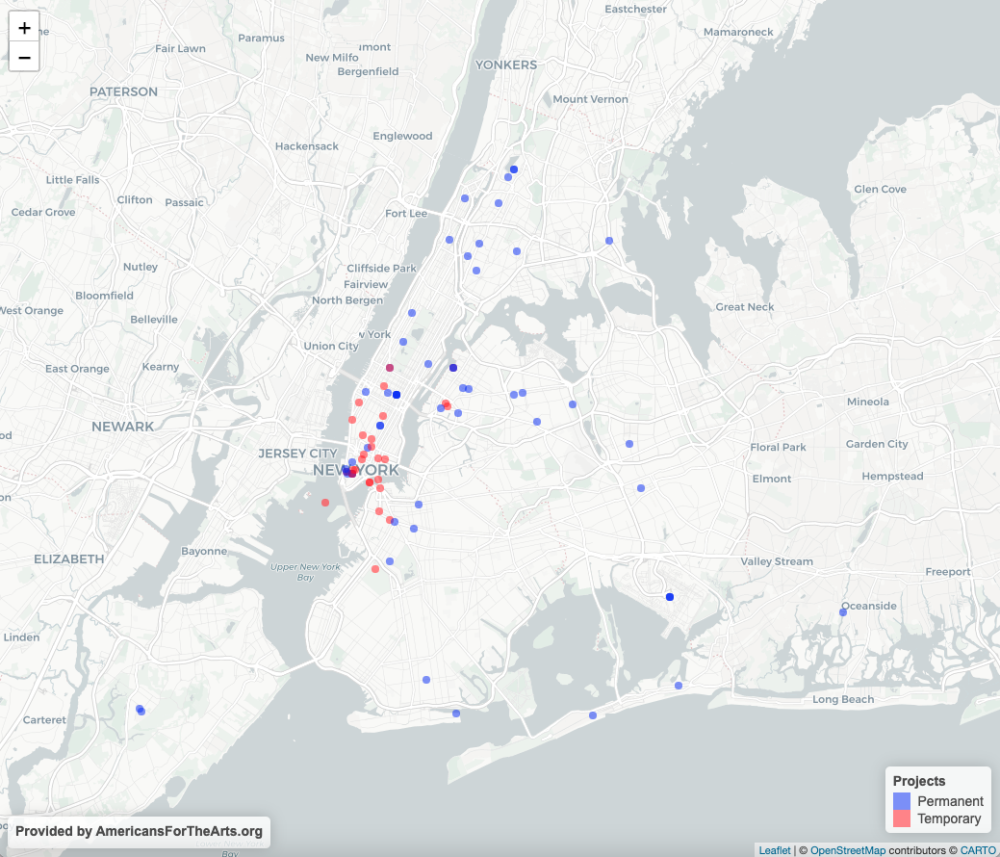

As a next step, we engaged in a series of hands-on exercises using publicly available collections metadata to interrogate what is knowable about a corpus remotely. We also employed a suite of digital tools, working primarily but not exclusively with R, an open-source programming language used for data analysis. However, these tools served as entry points to computational thinking and processes, and as a means to understand our current research environment rather than as instruments on their own terms. These datasets then served as the basis for the students to quantify and visualize the shape of collections, to map objects across both space and time, and to sketch the relationships between various art historical actors, through connected social networks.11 By cleaning, analyzing, and interpreting these datasets, we came to understand how difficult it is to categorize things in ways that machines can parse. This became immediately apparent, for instance, when we explored the MOMA collection, which offers its metadata openly through the museum’s API (application process interface) and updates it monthly.12 We started off with a dataset that was strategically filtered to include only MOMA’s single-artist paintings. But when students began to explore the larger dataset on their own and ventured into the much messier world of architecture, which involved multiple actors and media types, they began to understand the challenges of working with data that had not been pre-processed or streamlined. These exercises were presented with the conviction that the ability to manage and work effectively with digital assets and their associated metadata will be one of the most essential skills for the emerging art historian moving forward and thus must be integrated into art history curricula, however mundane these skills might seem. As Drucker suggested, “Understanding how digital methods work is a survival skill, not a luxury, or you are merely at the mercy of their effects.”13

The course tangled with questions that were situated at the nexus of digital humanities, art historical methodology, library science, and critical data studies, an orientation that led us in many unfamiliar directions. It was anchored by Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein’s Data Feminism, which was selected because of its incisive stance about the problematic ways in which data may be obtained, wrangled, visualized, and shared.14 Yet, the two authors set the tone for the class by pairing these cautions with a certain amount of hope, and indeed optimism, that responsible, informed, and creative practitioners can introduce modes of thinking and working that challenge the inequities and injustices brought about by data-driven approaches.

In addition, the course bibliography paired unlikely cohorts, joining art historical essays with selections from The American Statistician or the Journal of Statistical Software. This assemblage posed certain problems for the students, however. For instance, we delved into an important study coauthored by a team of statisticians and art historians, and published in PLOS ONE, that described how gender, race, and ethnicity were ascribed to thousands of artists represented in US museum collections. The students found this piece particularly challenging, even while the topics of museums, representation, and artists’ identities constituted common terrain.15 Throughout the semester, we had consistently upheld D’Ignazio and Klein’s proclamation to “show your work,” which emphasizes the need for transparency in data-driven research, particularly highlighting its human-centered character and emphasizing its processual contingencies, particularities, and arbitrariness. Even so, the students struggled to wade through the extensive statistical discussion about how gender, race, and ethnicity assessments were made, weighed, and then accepted or rejected in that PLOS ONE article. In addition, that particular project relied on workers employed by Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, the “crowd-sourcing marketplace,” which has been critiqued for its compensation structure and scrutinized for its central role in training and testing the datasets upon which many AI systems are based.16 While the authors of that article were absolutely clear about how they compensated the laborers who contributed to their project, the students grappled with the differing perspectives on this service, which was criticized in one arena and then mobilized as a major tool in another. The students had no problem understanding the objective of methodological transparency championed by D’Ignazio and Klein in an abstract way, but when it came to how these ideas could play out in practice, they experienced a disconnect. Their hesitations made me wonder—and also worry—about the possibilities for meaningful interdisciplinary collaboration, while major barriers of thinking, but also style and expression, hinder direct engagements between the humanities and the fields that rely upon computation and quantitative analysis. If aspects of that PLOS ONE article challenged my students, who were fully immersed in studying collections data, how would an art historian without any background benefit from its important findings?

The class was comprised mostly of art history graduate students (and one intrepid undergraduate) alongside graduate students from fields as diverse as anthropology, comparative literature, and from the College of Community Affairs and Public Administration. As such, not all the students were equally invested in the discipline and efforts had to be made to ensure that the content and the pressing nature of some of its core issues were relevant and legible across fields. Our class meetings, which alternated between in-person and virtual formats, were visited by many guests, namely librarians, visual resource curators, and art historians, who animated our discussions and demonstrated to the students how meaningful research related to art history was being conducted across various sectors of our own campus and those of other institutions. The course was also generously supported by a course development grant from the Binghamton Data Science Transdisciplinary Area of Excellence, which provided the resources to hire a graduate assistant, a PhD candidate in political science, who helped to iterate code and troubleshoot projects with the students. These visits and the lively makeup of the class allowed for productive exchange and also ignited my sense that these topics deserve to hold a central place in the art history classroom, even if they exceed the limits of the standard courses on theory, methods, or historiography. Yet, as Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi, Faith Kim, and Chelsy Monie expressed in their contribution to this series, the classic theory and methods syllabus would have to be renegotiated considerably in order to squeeze these topics in among a crowded roster of pressing concerns, both long-standing and newly arising, which vie for attention and consideration. By doing so, we may be able to move beyond the putative, and wholly inadequate, divide between the digital art historian and those who do not choose to adopt that title, a boundary that risks cordoning off digital engagements for a small number of practitioners, while also granting the large majority of art historians immunity from serious reflection on their own fundamental and thorough-going technological commitments.

Almost a decade ago, Drucker had distinguished the work of digitized art history from the computationally oriented approaches that sit under the umbrella of digital art history. At that time, she acknowledged the discipline’s widespread adoption of the resources provided by digital repositories, but indicated “that this conversion into digital access and delivery . . . has not had a ripple effect on the institutional foundations of art history.”17 Her distinguishing characterization of digital art history as a much more dramatic, ground-shifting, and also potentially threatening development is a meaningful one that has inspired much discussion and debate.18 Yet, bolstered by Milligan’s instigation to explore the “mundane questions shaping historical scholarship,” I ask that we look closely at the “working conditions” afforded by digitized art history as worthy of exploration on their own terms, regardless of how practical and procedural they may seem to be.19 For the field of history, Milligan calls expressly for the adoption of more explicit modes of project documentation. For instance, proposals should include how many digital photographs a researcher expects to take during an archival visit and their plans to ensure quality control in image capture. Moreover, he suggests a comprehensive practice of archival citation that indicates retrieval methods and underlines whether a source has been viewed from a microfilm reel, on the Internet Archive, or as a PDF downloaded from a library’s online repository. Additionally, he implores his colleagues to work more closely with archivists to better understand the shape and history of the collections that they consult, both physical and digital.

Indeed, the latter point directs us to confront the rapid and momentous changes in information management that are occurring within the world of GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums), but also to the general alienation of art historians from most of these developments, even while we actively benefit from the resources that they generate.20 Emily Pugh poses this divide in stark terms:

Our training has prepared us to conduct research and write scholarship in an information ecosystem that, to a large extent, no longer exists. The resulting gap—between our techniques for search and the nature of the information we are searching—is jeopardizing our ability not only to find information but also to evaluate the value and significance of the information we find.21

Pugh presents a significant issue for art history, but moreover for art history pedagogy. She underlines the fact that the librarians, archivists, and museum and heritage professionals who are associated with cutting-edge cultural institutions have produced conditions for research that exceed the technological capacities and objectives of art historians working within the context of university departments, a mismatched condition that Drucker had both perceived and predicted almost a decade ago.22 Indeed, it seems difficult to outgrow this perception of misalignment, as forward-looking institutions stake out new collaborative research landscapes that exceed the needs and aspirations of academic art history, as it is currently being carried out. If we are to acknowledge the weight of this current condition, and I think we should, we will also be jolted to consider how our classrooms and curricula may adequately prepare the art historians of the next generation to work meaningfully within this changing research environment.23

When this essay was written, Nancy Um was Professor of Art History and Associate Dean for Faculty Development and Inclusion at Harpur College at Binghamton University. She is now Associate Director for Research and Knowledge Creation at the Getty Research Institute. She is the author of Shipped but Not Sold: Material Culture and the Social Protocols of Trade During Yemen’s Age of Coffee (University of Hawai’i Press, 2017) and The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port (University of Washington Press, 2009).

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi and Yael Rice, who have been the best of collaborators. It is gratifying to see our continuing conversations take concrete form in this series. I am in awe of Nicole Archer, a committed editor with an ambitious vision, working creatively under challenging conditions. Many thanks to Emily Pugh for reading this over and generously providing valuable input.

- Ian Milligan, “We Are All Digital Now: Digital Photography and the Reshaping of Historical Practice,” Canadian Historical Review 101:4 (December 2020): 602–21. These arguments were recently augmented in Milligan, The Transformation of Historical Research in the Digital Age (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2022). The title of this essay evokes another book by the same author. Ian Milligan, History in the Age of Abundance? How the Web is Transforming Historical Research (Montreal: McGill University Press, 2019). ↩

- Staff members associated with the PhotoTech project at the Getty Research Institute carried out a very useful, but unpublished, field report that explored art historical research behaviors, based on data collected through interviews, a workshop, an online survey, and a discussion group, in 2020 and 2021. Tracy Stuber, Emily Pugh, Megan Sallabedra, Bryce Dwyer, and Melissa Gill, “PhotoTech Field Analysis Report,” last updated May 17, 2022. ↩

- On the latter, see Robert Nelson’s eloquent discussion of the slide-illustrated lecture and how it has shaped art historical exposition. Writing in 2000, Nelson concluded by imagining the ways in which digital technologies would have an effect on art historical writing and public presentation into the future. Robert Nelson, “The Slide Lecture, or The Work of Art History in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Critical Inquiry 26 (Spring 2000): 414–34. ↩

- Johanna Drucker, “Is There a ‘Digital’ Art History?” Visual Resources: An International Journal of Documentation 29:1–2 (2013): 7. ↩

- Stuber et al., “PhotoTech,” 7. ↩

- Ibid., Christina Kamposiori, Simon Mahony, and Claire Warwick, “The Impact of Digitization and Digital Resource Design on the Scholarly Workflow in Art History,” International Journal of Digital Art History 4 (2019): 3.11–3.27. ↩

- Nancy Um, “A Field without Fieldwork: Sustaining the Study of Islamic Architecture in the 21st Century,” International Journal of Islamic Architecture 10:1 (2021): 99–109. ↩

- Harald Klinke, “Big Image Data within the Big Picture of Art History,” International Journal for Digital Art History, 2 (October 2016), https://doi.org/10.11588/dah.2016.2.33527. ↩

- Nanna Bonde Thylstrup, The Politics of Mass Digitization (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019). ↩

- For more details, see WCMA Digital Project, https://artmuseum.williams.edu/wcma-digital-project/. ↩

- One of these exercises in interactive mapping, using the Leaflet package, was shared by the author in the virtual roundtable, “Teaching the Long Eighteenth Century,” convened by Sarah Betzer and Dipti Khera and hosted by the University of Virginia Institute of the Humanities and Global Cultures on April 23, 2021. Eleanore Neumann, with Anna Arabindan-Kesson, Nebahat Avcıoğlu, Emma Barker, Sarah Betzer, Ananda Cohen-Aponte, Dipti Khera, Prita Meier, Nancy Um, and Stephen Whiteman, “Teaching the ‘Long’ Eighteenth Century—A Conversation & Resources,” Journal18, 12 (Fall 2021), https://www.journal18.org/5891. ↩

- Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Collection, https://github.com/MuseumofModernArt/collection. ↩

- Johanna Drucker and Claire Bishop, “A Conversation on Digital Art History,” Debates in the Digital Humanities 2019, ed. Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein, https://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/read/untitled-f2acf72c-a469-49d8-be35-67f9ac1e3a60/section/3aedfd2c-280f-4029-b3f1-3e9a11794c01. ↩

- Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein, Data Feminism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020). Also available as a fully open-access volume: https://data-feminism.mitpress.mit.edu. ↩

- C. M. Topaz, B. Klingenberg, D. Turek, B. Heggeseth, P. E. Harris, J. C. Blackwood, C. O. Chavoya, S. Nelson, and K. Murphy, “Diversity of artists in major U.S. museums,” PLOS ONE 14:3 (March 20, 2019): e0212852, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212852. ↩

- Kate Crawford, Atlas of AI (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), 63–69. ↩

- Drucker, “Is There,” 7. ↩

- See the discussion on this topic in Drucker and Bishop, “A Conversation,” and Nuria Rodríguez-Ortega, “Digital Art History: The Questions that Need to Be Asked,” Visual Resources: An International Journal on Images and their Uses 35:1–2 (March–June 2019): 7–8. ↩

- Milligan, The Transformation, 4. ↩

- Emily Pugh, “Art History Now: Institutional Change and Scholarly Practice,” International Journal for Digital Art History 4 (2019-21): 3.47–58; Anne Helmreich, Matthew Lincoln, and Charles van den Heuvel, “Data Ecosystems and the Future of Art History,” Historie de l’Art 87 (2021): 45–42. ↩

- Pugh, “Art History Now,” 3.48. ↩

- Drucker, “Is There,” 12. ↩

- This topic was taken up in a generative virtual roundtable on the teaching of digital art history at the graduate level convened at Penn State University in June 2020. Thanks to Elizabeth Mansfield, Head of Art History, and John Russell, Digital Humanities Librarian, for organizing that thought-provoking session. ↩