On a luminous winter day in late January 1991, I saw a white projectile gliding noiselessly across Baghdad’s crisp blue sky. It was the infamous Tomahawk cruise missile, which featured prominently during the Gulf War.1 It was a casual encounter that morning, a brush with the most technologically sophisticated war in history.2 I still recall how I wondered, even at that young age, where that missile was going, because it was clearly on its way to destroy more of our city. A few weeks later, apocalyptic clouds loomed over the skies, the result of the Iraqi regime burning Kuwaiti oil fields, when it was forced to retreat by the allied forces.3 The following morning earthworms blanketed the ground in nearby parks, in a mass extermination brought about by the acidic rain that saturated the earth. Little did we know that what we experienced during those days was one of the world’s worst-ever environmental disasters.4

Such memories are often destined to be buried, forgotten like many other atrocities the region has had to endure. Recalling these memories may also amplify the representational fatigue associated with parts of the Arab world (where Arabic speakers are the majority, the land stretching from Southwest Asia to North Africa), often depicted as the locus of perpetual turmoil, constantly relapsing into a nonstop chain of conflicts, ranging from organized warfare to senseless petty strife. However, aside from underlining my personal connection to the region, to share these recollections is to emphasize how no one is left unharmed by war—psychologically, physically, economically, socially, and environmentally.

Warfare is not an abstract event seen only on screens, channeling a reality elsewhere, and it is not something that strictly befalls only “others” in those faraway, wild lands. To dismiss such memories is to overlook the fact that, as Jairus Victor Grove cogently argues, militarization and organized violence are some of the primary causes of global environmental degradation.5 It is also to overlook a pivotal yet often-suppressed dimension of our collective existence, emphasized by Achille Mbembe: the war enterprise—rooted in the history of colonialism, slavery, and genocide, and sustained by extractive capitalism—is a force that continues to shape much of the world.6

In this paper, I examine artworks by five artists who directly or implicitly tackle the fraught yet elusive subject of global warfare. These works form the basis of my argument, that contemporary art can reveal the far-reaching and lasting consequences of warfare. These specific artists demonstrate the multifaceted nature of conflict and its utterly devastating impact on human and other lives as well as the landscapes that humanity inhabits. While warfare indisputably affects the entire world, I would like to emphasize here the conflicts that rage in troubled Arab geographies, specifically in Iraq, and what these can say about the environment globally.

Representations in the media aside, ongoing warfare in a number of Arab countries manifests the imperial dreams of dominant powers: these conflicts are a microcosm of global ideological rivalries and the fierce planetary competition for resources.7 In other words, instability here—which manifests itself not only in Iraq but also in several other places, including Egypt, Lebanon, Libya, Palestine, Syria, and Yemen—encapsulates the dynamics of global conflicts, as these collide and erupt in episodes of environmental catastrophes and mass violence. The region, therefore, can gauge the impact of warfare on the environment, viewed here holistically as the world in which humanity collectively dwells, with all its layers, interconnections, and unfathomable complexities, beyond the customary emphasis in traditional environmental discourse on the loss of natural habitat or climate change.8 Expanding existing definitions of the “environment” is not just a new trend in art historical scholarship. It is necessitated by the nature of warfare itself: conventional definitions have only contributed to covering up the many, and often invisible, ways in which conflict impacts life worldwide.

In this inquiry, I bring together works by Mona Hatoum, Abbas Akhavan, Thomas Hirschhorn, Shona Illingworth, and Ali Eyal. While these five artists hail from diverse cultural backgrounds and represent different generations and artistic practices, I will argue that each of their works—articulated in a variety of media—conveys a salient and unique facet of how conflict affects the environment at large, while all being situated within Iraq as a consistent reference. Not only do these artists chart new avenues for rethinking the environment, beyond what is possible in the natural sciences or environmental humanities, but they also address the environmental repercussions of warfare in ways that elude the conventional rubrics of what is known as environmental or ecocritical art.

Before delving into the artists’ work, it is important to note that those who study modern or contemporary art from or about Iraq have not necessarily examined the multifaceted impact of warfare on the environment.9 Therefore, I would like to account for art historical literature that analyzes the intersections of conflict and the environment more broadly, and as these manifest themselves in Arab geographies more specifically. My approach here is distinct from existing art historical scholarship, which tends to view the environment from an ecological vantage point, usually focusing on natural and nonhuman dimensions. Moreover, accounting for more holistic definitions of the environment, with its wide-ranging global entanglements, is a nascent branch of inquiry in art history. This is conveyed in an impressive 2021 volume edited by T. J. Demos, Emily Eliza Scott, and Subhankar Banerjee, exploring how contemporary visual culture reflects on the climate crisis and presenting pioneering scholarship to argue that artistic practices can indeed help expand and complicate the ways in which the environment is understood, providing comprehensive theoretical and historical frameworks to study the interrelated phenomena that define the climate.10 In 2020, Demos published an outstanding exploration of the entwined crises—environmental, sociopolitical, and economic—threatening to bring the world to an end, examining art practices that identify these pressing issues and chart hopeful futures beyond the impending apocalypse. While Demos expands the definition of “the climate” using an intersectional framework, insufficient attention is paid to the role that militarized conflict plays in global environmental degradation.11

On Arab geographies more specifically, Diana K. Davis and Edmund Burke have made a significant contribution, unpacking the (Western) imaginaries that often characterize the region: owing to what they describe as “environmental orientalism,” the environment of these lands has not only been overlooked by postcolonial scholars but also historically denigrated, because such dismissive imperial representational tropes could legitimize colonial control, schemes of “improvement,” and all forms of military interventionism.12 Some scholars have interrogated the representations of conflict in the region. For example, Chad Elias examines the context of Lebanon, arguing that the country’s wars were not merely military affairs but conflicts in which the production and consumption of images played a pivotal role. He examines how the work of Lebanese artists, such as Walid Raad (b. 1967), cannot be reduced to questions of trauma or disaster but opens up an inquiry foregrounding the manner in which the war experience evades concise and neat summaries.13 Dora Apel expands this discussion, looking at the emancipatory potential of images, especially documentary artistic practices, in representations of war and in countering its violence.14 Other scholars have studied terrorism as a prominent facet of violence in Iraq and the region, and the performative aspects of warfare—both in influencing public opinion and in subverting hegemonic narratives, when used by individuals and groups at grassroots level.15

My approach in this paper attempts to bridge emerging scholarship that probes the overlaps between visual arts and the environment, on the one hand, and more specific explorations of how warfare in Arab geographies is represented, and its repercussions beyond the region, on the other. I argue that contemporary art opens a window to critically rethink the impact of conflict on the environment, writ large, in ways that complement and expand the limited lens of more scientific and quantitative disciplines, while drawing attention to the global footprint of warfare that consumes parts of the region in question. Indeed, it can be daunting to discuss the pernicious and pervasive impact of organized violence along with environmental degradation—these grave issues can easily dwarf discussions of individual artworks. However, art, with its power to critically observe and eloquently comment on challenging subjects, allows us to gain insight into oppressive conditions that threaten our collective survival.

I recently encountered a work by Mona Hatoum (b. 1952), which exposed a subtle, and largely unknown, dimension of conflict in Iraq. In late 2020, news outlets reported that Hatoum, among other artists, participated in a fundraising campaign that highlighted the fires destroying Iraq’s arable land, endangering the livelihoods of farmers and compounding the plight of displaced refugees who rely on local produce.16 The fires have been blamed on a number of causes, including arson by terrorist groups, as well as military strikes by neighboring countries.17 These fires, however, are but one dimension of a larger narrative involving farmers in the northern parts of the country who returned to their fields after ISIS fighters were expelled; the struggles of the remaining Yazidis, who have survived genocide over the past few years; and Iraq’s humble annual harvest, which continues to be vital to one of the world’s richest oil producers. Most importantly, these fires suggest that even primitive acts of economic sabotage form part of ongoing warfare in this region, often invisible to the world.

Hatoum’s SE (2020) addresses this attack on land and livelihood. The two-dimensional work features black acrylic paint made with ashes collected from the scorched fields, applied on top of a light blue paint layer, all executed on watercolor paper and mounted on white card.18 Formally, the work is similar to lithographs the artist produced two years prior, most of which are untitled (with the word “fence” in parentheses, alluding to what is being evoked by the lattice pattern). Unlike those previous lithographs, where the pattern is applied as an additional layer, here the lattice is created by scraping off the black paint to reveal the blue underneath.19 As a conceptual artist, Hatoum creates work that is often embedded with multiple connotations and imbued with witty commentary; grid patterns in particular have been a recurring motif, referencing forbidding enclosures, barriers, and national borders. Capturing uncanny paradoxes, SE is no different: it presents a seemingly hopeful act of clearing the scorched earth to reveal a blue surface, which could signify a clear sky, the antithesis of the dark smoke emitted by the fires, or water, which could extinguish the flames. But this act is simultaneously unsettling, uncovering something menacing: a chain-link fence, which speaks to the reality of segregation in several countries in the region, where access and mobility are thwarted at an astonishing scale. While Hatoum has been invested throughout her career in challenging stereotypes about Arab cultures and destabilizing perceptions of these geographies, there is an implicit acknowledgment here that divisions have become the new vernacular. This is echoed by the fact that the pattern also evokes a fragment of a textile, especially the checkered Palestinian kaffiyeh (another motif that the artist has explored previously), as though to suggest that such calamities have become a second skin for the inhabitants of parts of this region, like Iraq. Hatoum’s work therefore goes beyond mere commentary; it denounces the military-industrial complex itself.

Hatoum’s work is instructive, because her four-decade career speaks to how parts of this region have become the fulcrum of prolonged conflicts and frequent international interventions. The so-called clash of civilizations has manifested itself most ruthlessly within Arab-Muslim geographies, simultaneously threatening the stability and future of the entire planet. And if the region is often portrayed as the furnace where the fires of global conflicts rage, Iraq is certainly its crucible—a battleground for the American administration’s worldwide crusade on terror, and for proxy wars fought between regional powers. The country has tragically become synonymous with warfare, chronic unrest, displacement, international sanctions, and the general collapse of state sovereignty since the 2003 American-led invasion.20 Created by the British colonial administration in 1921, Iraq has been rocked by political instability for decades, but it is the 2003 American-led invasion that became the most severe crisis the country has ever experienced—sending shockwaves felt the world over.21

For instance, the immense failure of Iraq’s “liberation” has forever changed American military operations, forcing the United States to rely on remote combat over traditional ground troops; moreover, and in addition to shattering the credibility of Western engagements in Arab geographies, the invasion further destabilized the region by intensifying intervention from multiple foreign powers, fueling sectarian violence, exacerbating the refugee crisis, empowering terrorist groups like Al-Qaida and ISIS, and unleashing countless militias.22 Even though metropolitan centers in the West remain relatively safe and seemingly distant from the terrains usually afflicted with unrest, warfare has equally had a global footprint: ecological catastrophes, fluctuations in oil supplies, lost agricultural harvests, economic failures, solidarity among extremists everywhere, and the rise of far-right and xenophobic political parties that feed on popular resentment of an influx of immigrants fleeing the region, among other, fundamentally planetary, consequences.23

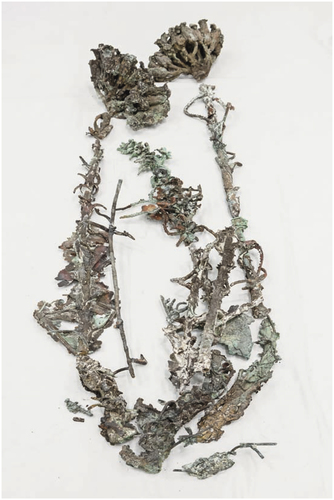

Contemporary art can shed light on the global impact of these conflicts, including dimensions that remain largely occluded, or even deliberately censored. Alongside the primitive guise of warfare evinced by Hatoum’s work, the technologically advanced attacks that Iraq endured have had a far more pernicious impact on the region’s ecology—something that other artists, such as Abbas Akhavan (b. 1977), have tackled. In his work Study for a Monument (2013–present), the artist sought the expertise of horticulturalists in identifying native plants of Mesopotamia. Akhavan magnified the size of these plants—to approximate a scale common in commemorative monuments—and then cast the wax models in bronze before presenting them in constellations strewn across cotton sheets on the gallery’s floor. The work connotes the ecological devastation, particularly the detrimental impact on the vulnerable flora of this part of the world, brought about not only by the 2003 invasion but also by previous wars.

In Akhavan’s work is a reminder that the American invasion not only destroyed Iraq’s infrastructure, and thus the country’s capacity to address environmental damage, but also had barely studied ramifications on its airspace. Iraq’s air quality is so poor that it poses serious health risks; the air is laden with heavy metals, such as lead and aluminum, and lung-damaging fine particles, which increase asthma and other respiratory and cardiovascular issues.24 Dust storms have increased after years of war, partly because of the decimation of large swaths of the land’s green cover (through bombardment as well as frenzied real-estate speculation and the lack of proper regulation under post-2003 governments, which supplanted agricultural lands with new urban developments); the finer sand particles carried by these storms, the result of intense military action across the country, not only cause respiratory problems but have also been found to contain traces of depleted uranium, linked to a surge in cancer and birth defects.25 The sources of such pollutants are said to vary, from attacks on the Tuwaitha Nuclear Research Center (by Israel in 1981 and the United States and its allies in the 1991 Gulf War, and then the looting of radioactive material after the 2003 invasion) to the enormous quantities of munitions utilizing depleted uranium dropped by US and British forces throughout Iraq in the 1991 and 2003 offensives.26

The loss of green cover, to which Akhavan alludes, has repercussions that also extend well beyond Iraq, including the record-breaking hot weather the country and the rest of the region have been experiencing, setting a precedent for a planet where climate change is already a serious threat.27 The blazing heat is not only making living in the country untenable, especially given the collapse of basic services such as electricity since 2003, but ruining crops and the remaining vegetation, which wither under the merciless sun.28 In recent years, droughts—and neighboring countries tightening Iraq’s water supply—have reduced cultivable land by half, and livestock by around a third.29 The effects of Iraq’s changing climate will only intensify: droughts and water shortages are expected to worsen as temperatures soar, and salinity and pollution to increase.30 Iraq’s anticipated calamities reflect those of other Arab countries—the rising heat will affect water resources, with wide implications for social and economic conditions across the entire region.31

Akhavan, as an artist of Iranian heritage, offers his bronzes in sympathy, as a tribute to the ecology of Iraq, challenging stereotypes that characterize these two neighbors as archetypal nemeses (especially after the brutal eight-years’ war).32 The remnants of Iraq’s plants in Akhavan’s work are distorted in scale, petrified, oxidized, fragmented, and fallen. If this is a study for a monument, as the title suggests, then it is a funerary monument to destruction, degradation, and disappearance. The melancholic undertones stem from mourning the loss of frail elements of this ecology, gradually rendering Iraq’s landscape uninhabitable. The scalar shift and the way in which the pieces are displayed, evoking bodies or limbs, bring to mind the harrowing scenes of the aftermath of recent suicide bombings, or images of bodies exhumed from mass graves. Indeed, more than a commentary on ecological damage, Akhavan’s work also brings up the human toll of war—which may seem the most obvious dimension of conflict, yet is one that remains obscured, contested, and excised from discussions about the environment, as though the human and natural are incommensurable.

In the few years following the 2003 invasion, it is believed that hundreds of thousands of Iraqis have lost their lives through violence.33 Civilian deaths have been caused by foreign military personnel, drone strikes, private security contractors like Blackwater, car and suicide bombings, assassinations and retaliatory attacks launched by various militias, terrorist activities, and government forces (targeting dissidents, for example); this is not to mention those who have vanished without a trace, or perished owing to malnutrition, poor health, or other factors brought about by conflict. Warfare has also resulted in vast displacement of Iraqis, creating one of the largest groups of refugees in the region. Just since 2014, when ISIS took over large swaths of northwestern Iraq, there have been over three million displaced Iraqis, with hundreds of thousands living in refugee camps or informal settlements—these people have joined those displaced during the 2003 invasion and the instability that followed.34 Compounding the monumental loss of human life, and the forced displacement of many, is the pain and suffering of those who survived.

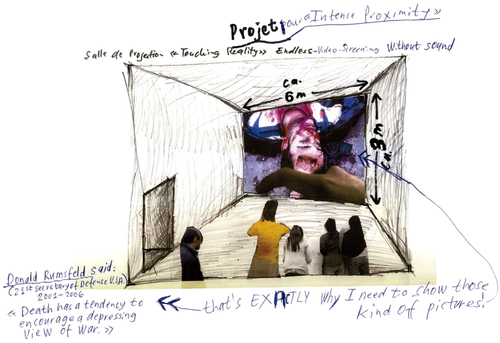

The environment cannot be truly understood without accounting for the humans who shape, and are shaped by, the world. Few contemporary artists have taken on the astounding scale of death caused by war as bluntly as Thomas Hirschhorn (b. 1957). In relation to Iraq specifically, his work speaks to not only the intimate relationship between the detrimental impact of conflict and its human toll but also how human beings are often forgotten in discussions about the environment. In Touching Reality (2012) the viewer enters a darkened room through a doorway left casually open. A wall-size video projection fills the opposite side of the room, showing a hand scrolling through gruesome images of dismembered and burnt corpses, mangled flesh, disfigured heads, and blood pools, alongside other images of the carnage of war eschewed by conventional media. The fingers navigate the images dispassionately—at a pace neither hurried nor contemplative—zooming in on details before moving on mechanically to the next image. This “moving collage,” as Hirschhorn describes it, borrows images from Iraq and other places and represents the global disaster that is war—a facet of humanity typically concealed. As war is consumed through impersonal technologies of mediation, there is a public amnesia to its reality, which, Hirschhorn contends, is far from innocuous: the invisibility serves to support the war effort.35 There is a play on words in Touching Reality, with “touching” implying sentiments of sympathy or appreciation but also how the fingers are barely “touching” the images of war, with startling indifference—or, that the work is only “touching” upon the reality of war, which remains beyond representation, considering the annihilation it brings about. The work raises ethical questions about the use of images of the deceased (without consent), or how this use might be hurtful to the traumatized families of the “anonymous” victims being gazed at voyeuristically within art spaces. The work is also heart-wrenching: most visitors leave the space instantly; looking at the corner of the screen alone induces nausea. But there is something powerful about this brazen confrontation with death—the work is unflinchingly cruel, and certainly problematic, but it comes as close to a representation of the abrasive savagery of war as one could imagine.

In his comments on the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Hirschhorn repeats a statement attributed to the former American secretary of defense, Donald Rumsfeld: “Death has a tendency to encourage a depressing view of war,” implying that it is in the interest of the architects of war to cover up the human toll of organized conflict.36 Ongoing warfare, however, obscures a lot more than bloodshed. It obfuscates issues facing the region’s natural habitat and its populations alike, such as soaring temperatures, intensifying droughts, rising sea levels threatening coastal cities, water scarcity, and worsening air quality. These are in turn exacerbating existing economic disparities and other sociopolitical predicaments that have plagued the region for decades—brought about by the legacy of colonialism, and subsequent oppressive regimes—and have become further complicated in recent years. Such predicaments include widespread poverty, unprecedented civil and social polarization, pervasive corruption, human rights violations, declining gender equality, dire conditions for minorities, the collapse of educational infrastructure, and the overall lack of social security. And this is despite the region’s enormous oil wealth—but it is not surprising that contemporary warfare would conceal this specific, and critical, dimension of conflict.

The work of Shona Illingworth (b. 1966) examines the complex links between oil and conflict, tying extraction and warfare on the ground to the airspace above battlefields. In Topologies of Air (2021), the viewer enters a darkened blue room, to be enveloped with sound while facing a three-channel video projection. Addressing an epic array of subjects, the ambitious work presents the sky as a densely colonized space, where environmental issues overlap with technological developments and emerging power structures, not to mention the detrimental impact of such collisions on life on earth.37 Illingworth makes implicit references to Iraq: at one point the voice-over talks about enormous sandstorms laden with radioactive particles in a war-ravaged land; another voice, that of a witness, discusses an attack that decimated all forms of life, evoking the chemical weapons used by Saddam Hussein’s regime against Iran and the Kurdish regions in northern Iraq; then there is the generic yet all-too-familiar footage of a British Royal Air Force fighter jet taxiing on a tarmac, reminiscent of widely circulated imagery from the Gulf War and 2003 invasion. Footage depicting the oil industry is woven throughout the work, highlighting the insidious role fossil fuels play in the myriad ways in which the globe, along with its skies, is occupied: pumpjacks forcing oil out of ground wells, refineries churning out oil products day and night, the transnational labor force employed in these facilities, and vast commercial ports, all of which point to an insatiable international appetite for this resource.

Illingworth’s work points to the fact that oil is a most vital resource, supplying much of the energy needs of the globe, and that extractive capitalism has structured the politics of the modern world. Indeed, while oil and parts of the Arab world often appear to be synonymous, oil is a transnational commodity: as Timothy Mitchell has argued, modern societies everywhere, along with their political structures, have come into existence through the processes of extracting and consuming fossil fuels; Arab geographies happen to be at the confluence of this correlation, and Iraq, with its vast oil resources discovered early in the twentieth century, is a crucial node.38 This is partly what Illingworth explores in her work; her installation is also a reminder that airspace is tethered to the ground, suggesting that warfare and extractive capitalism, largely anchored in Arab geographies—some of the footage is shot in the Gulf—are inseparable, that violence, whether bound to the ground or aerial, is the tool of empire, hurtling the planet toward a tragic end.

Global warfare requires oil, and this need yields disastrous environmental outcomes. This is why oil was a central reason for the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The occupation made oil available for international firms (including Halliburton, once headed by Dick Cheney, a staunch advocate of war on Iraq), increasing production capacity by almost half, while many Iraqis now live in abject poverty, and the majority struggle to find petroleum-based products locally.39 Even in those rare cases where attending to the environment appeared to be a priority after 2003, this often concealed more sinister motives. For example, in the attempted restoration of the delicate ecology of the marshes in southern Iraq—severely damaged in the 1990s when the Hussein regime quashed a grassroots Shi‘a uprising—the rehabilitation of these wetlands became a political tool for the United States and local governments intent on opening doors to war profiteering by international corporations keen on gaining access to oil.40 Securing oil in this region means controlling the world, which explains why the US spends more on its military than any other nation globally; maintaining this force also requires enormous amounts of energy, mostly supplied by fossil fuels.41 In fact, around the time of the 2003 invasion, the oil consumption of the US Department of Defense alone was almost equivalent to Iraq’s consumption as a nation.42 Domination through contemporary warfare can succeed only if it can secure access to such resources, which, it may be argued, by default encourages or necessitates military intervention in oil-rich regions.

These facts may be freely available, but contemporary artists bring them to collective consciousness in comprehensible and visual ways, affirming art’s capacity and commitment to addressing some of the most pressing issues of our time. Beyond mere critique, the work of the artists I discuss here also reconsiders the relationships between warfare and the environment in ways that transcend the customary focus on climate change, illuminating issues that geopolitics tends to overshadow or attempts constantly to suppress, and revealing the deep trauma and the staggering weight of contemporary warfare the world over.43 Bringing together artists who interrogate the consequences of modern conflict can likewise help render the environment in guises that exceed the natural and scientifically measurable. By no means are these artists’ perspectives exhaustive, but their works provide nuanced representations of how conflict is deeply enmeshed within our daily lives, and how the international community is complicit—through silence, blissful ignorance, or direct culpability—in the devastation being wrought on the environment today, globally.

It is, however, one thing to account for the physical traces of warfare but another to fathom, or even represent, the more intangible dimensions, which might in fact constitute the most haunting damage—especially for those who have lived through, and survived, these conflicts. There has indeed been a monumental loss of life, in addition to a huge toll in disability and serious physical health issues, but Iraq also faces an epidemic of psychological disorders, induced by years of widespread violence. This is a serious problem for those with a lived experience of violence in a destabilized country where a “brain drain” has led to a lack of qualified professionals trained in addressing the trauma of violence: health specialists have emigrated for better living conditions or been forced to flee to escape persecution, and the educational system has imploded more recently. Those affected by the precarity in Iraq endure deep emotional scars that will likely last for generations, whether treated or not. The country’s youth has borne the brunt of ongoing warfare, with millions orphaned (it is estimated that over two-thirds lost parents after the 2003 invasion, and more than half have suffered some symptoms of depression, with a similar number grappling with posttraumatic stress disorder); many children suffering unspeakable distress, with chronic anxiety and nightmares; and a majority experiencing learning difficulties owing to the ongoing lack of security.44

Ali Eyal (b. 1994), an Iraqi artist who grew up in Baghdad and witnessed the 2003 invasion and its bloody aftermath, has produced a penetrating work that alludes to the intangible dimensions of warfare, particularly for Iraqis themselves, suggesting how mental health could be an integral dimension to our understanding of the environment at large. The wall-mounted piece consists of inscriptions and sketches drawn on the surfaces of thirteen multicolored pillowcases, all stitched onto a gray bedsheet, creating a supple composition gently falling from its suspension points. Tasked with the challenge of painting a portrait commemorating his cousin, who died while fighting ISIS insurgents in northern Iraq, and having stared at the canvas for a long time—which inspired the work’s title, Painting Size 80x60cm (2018)—Eyal opted instead to capture a series of dreams he had about the deceased. The inscriptions trace the movements of his head as he turned over in his sleep, with the paint gradually disappearing as memories of the victim faded. The medium of this work constitutes a collective memorial of sorts, as the pillowcases were gathered from family and relatives in Baghdad; cotton sheets also have a significance that only locals know, as they are used to fill gaps left by wounds before a corpse is buried. But the pivotal concern of the work is rather ethereal: it is to capture not palpable traces of the victim but his disappearance, to come to terms with his absence, and to embrace the emptiness that follows loss.45 Poetic, cryptic, amusing, nonsensical, and agonizing all at the same time, Eyal’s dreams hint at the psychological weight of conflict. The work’s striking gentleness betrays such pain, tenderness, and longing, speaking to a Proustian desire to be suspended within the realm of memories and dreams, to cherish whatever is left of a lost loved one, even if it is only inside one’s head.

The display evokes the metaphor of hanging out one’s laundry for everyone to see. But these are not arbitrary pieces of personal clothing—these are bedding textiles, signaling a parallel realm of reminiscence, perhaps the only realm left with any vestiges of joy for Iraqis. Eyal’s profound revelations help in framing the environment differently. In his work is a strong warning: for the world to engage with the environment solely through the narrow and myopic lens of climate change (focusing only on gas emissions from cars and factories, or putting the burden on the shoulders of ordinary citizens by calling for less consumption or more active recycling and reuse of resources, for example) is to make a monstrous and glaring omission.46 Instead, to account for the global impact of warfare, and to understand the environment in a more holistic sense, we must acknowledge that our experiences are mutually constitutive. We must underline our interdependence everywhere, and center links between our lives and the lands and skies we inhabit. We must also realize that warfare anywhere is an attack on people and physical things everywhere, just as it is an assault on the other beings that coinhabit this world, our shared frail ecology, and the possibility of our collective survival.

The works I analyze in this paper speak to the entangled relationships between conflict and the world at large, just as they bring into sharp relief the potent capacity of art to elucidate alternative imaginaries of the environment. The artists discussed here offer some of the most compelling reflections on the multiple dimensions and experiences of conflict that I, as a survivor, have come across. Presented together, they jointly paint a more complex picture of warfare and its multifaceted repercussions than could be achieved by a single artist or scholar. I hope that the works convey, just as they impressed on me, that to imagine that bombs falling on the homeland of a little child in some faraway place do not concern the environment in our interconnected world, or affect the rest of the globe, is to be delusional.47 Eyal’s work delivers a complementary message, emphasizing the significance of narratives told by those who have been subjected to organized violence, and whose voices are often unheard. More critically, his work holds promise for further research, which may identify other obscured dimensions of the vicious impact of warfare on the environment, the true scale of which is only beginning to become intelligible.

Amin Alsaden is a scholar, curator, and educator whose work focuses on transnational solidarities and exchanges across cultural boundaries. His research explores modern and contemporary art and architecture in the Arab and Muslim worlds, particularly post–World War II Iraq, examining the manner in which precarious archives and scarce resources shape lopsided global narratives. He is currently based in Toronto, Canada.

- The first use of the Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM) in a military operation was during the Gulf War. See US Navy Office of Information, “Tomahawk Cruise Missile,” United States Navy, April 26, 2018. ↩

- John A. Warden III, a US military colonel who was behind Operation Instant Thunder, an American air strike launched during the Gulf War, believed that the air campaign of 1991 was a watershed moment in the history of war, one that provided a model well into the twenty-first century. Warden, “Employing Air Power in the Twenty-first Century,” in The Future of Air Power in the Aftermath of the Gulf War, ed. Richard H. Shultz Jr. and Robert L. Pfaltzgraff Jr. (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Press, 1992); 81–82. ↩

- Iraqi troops burned nearly six hundred Kuwaiti oil wells and released around two to three million barrels of oil into the Persian Gulf, apparently to hinder allied ground advancement and thwart air strikes by obscuring Iraqi targets. See Marc A. Ross, “Environmental Warfare and the Persian Gulf War: Possible Remedies to Combat Intentional Destruction of the Environment,” Penn State International Law Review 10, no. 3 (1992): 515–39. ↩

- The Kuwait oil fires are often listed as one of the worst environmental disasters in human history. See, for example: Joe Myers, “These Are Some of the World’s Worst Environmental Disasters,” World Economic Forum, April 20, 2016; and Gilbert Cruz, “Top 10 Environmental Disasters,” Time, May 3, 2010. ↩

- Grove suggests that Euro-American politics has for centuries been developing techniques for engaging with the world that are fundamentally antithetical to humanity’s survival. He emphasizes that contemporary warfare is not an anomalous or occasional event but a routine practice for the global political order. Jairus Victor Grove, Savage Ecology: War and Geopolitics at the End of the World (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 4. ↩

- Mbembe suggests that global democracy has embraced the same violent impulses that propelled colonialism, relying on war today as a survival strategy, paradoxically bringing about a global exit from democracy. He writes: “The hitherto more or less hidden violence of democracies is rising to the surface… the political order is reconstituting itself as a form of organization for death.” Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics, trans. Steven Corcoran (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 6–7. ↩

- Mbembe writes: “Democracy, the plantation, and the colonial empire are objectively all part of the same historical matrix … at the heart of every historical understanding of the violence of the contemporary global order” (Mbembe, Necropolitics, 23). ↩

- Perhaps the closest definition of “environment” to what I mean here is: “The physical surroundings or conditions in which a person or other organism lives, develops, etc., or in which a thing exists; the external conditions in general affecting the life, existence, or properties of an organism or object.” I also wish to underline another definition: “The social, political, or cultural circumstances in which a person lives, esp. with respect to their effect on behaviour, attitudes, etc.; (with modifying word) a particular set of such circumstances.” Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “Environment, n,” accessed September 2020. ↩

- To my knowledge, scholars such as Saleem Al-Bahloly, Sarah Johnson, Silvia Naef, Elizabeth Rauh, Nada Shabout, and Zouina Ait Slimani, who study the history of modern or contemporary Iraqi art, have not examined this subject; Rauh has started to study the environment of Iraq, with a focus on the natural landscapes of the south. The only exception is Rijin Sahakian, who has written about the impact of warfare on contemporary artistic production and the experiences of artists emerging from Iraq following the invasion, but has not examined the environment specifically; she has published a critical article about the 2019 protests in Baghdad and other provinces, drawing links to global climate change activism while highlighting how the international pursuit of Iraqi oil has been a primary cause of the population’s plight. Sahakian, “Extraction Rebellion: A Green Zone of Hope,” n + 1, November 26, 2019. ↩

- The editors chose to use the term “climate,” instead of “environment,” as a metaphor for the entanglements of sociopolitical, technological, and economic dimensions, among others, with ecology, thus emphasizing that the natural cannot be separated from the cultural and that the two are mutually defining and deeply intertwined. However, even though one of the major themes explored by this volume is “climate violence,” there is no contribution directly engaging with warfare or extractive industries in Arab geographies. T. J. Demos, Emily Eliza Scott, and Subhankar Banerjee, eds., The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change (New York: Routledge, 2021). ↩

- Demos does mention warfare as one of the factors contributing to the world’s demise, but seems to posit the West as savior, failing to solve the world’s environmental issues only because of “international environmental racism in the developed world’s refusal to share technologies and resources and assist poorer countries,” overlooking the fact that Western engagement in Arab geographies extends to active destruction through warfare. T. J. Demos, Beyond the World’s End: Arts of Living at the Crossing (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 13. ↩

- Although not strictly art historical, the important contributions to this book consider political, social, economic, and other dimensions of the environment, exploring both Western imaginaries and resistant local conceptions situated within these geographies. Diana K. Davis, “Imperialism, Orientalism, and the Environment in the Middle East: History, Policy, Power, and Practice,” in Environmental Imaginaries of the Middle East and North Africa, ed. Davis and Edmund Burke (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2011), 1–22. ↩

- Elias is not necessarily concerned with environmental issues or warfare’s impact on natural ecologies; his analysis remains open-ended, however, emphasizing regional and international geopolitical involvement in local conflicts, and how war has an impact that often eschews conventional narratives. Chad Elias, Posthumous Images: Contemporary Art and Memory Politics in Post–Civil War Lebanon (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018). ↩

- Apel has not examined the environment, but she does focus on war in Iraq and the rest of the region, recognizing the vast, unacknowledged, and hidden footprint of violence, which often resists representation. See Dora Apel, War Culture and the Contest of Images (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012). ↩

- Jonathan Harris critically examines the current state of global emergency, generated by nonstate and state-sponsored terrorism, seen through the prism of the arts. Like warfare, terrorism is revealed as a complex, ever-shifting, and multilayered phenomenon in which representation and performativity implicate the whole globe, not just Arab or Muslim geographies. Harris, ed., Terrorism and the Arts: Practices and Critiques in Contemporary Cultural Production (Milton Park, UK: Taylor and Francis, 2021). Lindsey Mantoan also suggests that war is highly performative. Its rhetorical, representational, and theatrical strategies can be deployed by governments to manipulate the public and by artists or intellectuals to oppose warmongering or ameliorate the devastating effects of conflict. She convincingly argues that the Iraq wars employed performance—via deceit, propaganda, and spectacle—as a powerful weapon. Mantoan, War as Performance: Conflicts in Iraq and Political Theatricality (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International, 2018). ↩

- The campaign was run by London-based Migrate Art, under the title “Scorched Earth,” engaging fourteen artists to create works, proceeds from the sale of which would support charities (through an auction at Christie’s). See Caroline Goldstein, “Rachel Whiteread and 13 Other Art Stars Are Selling Work Made from the Scorched Fields of Iraq to Benefit Refugees,” Artnet News, September 3, 2020. ↩

- The fires are often described as “mysterious,” with wide speculation about the perpetrators and motives, but ISIS has reportedly claimed some of the attacks. See Simona Foltyn, “Iraq’s Burning Problem: The Strange Fires Destroying Crops and Livelihoods,” Guardian, August 15, 2019; Tom Westcott, “Crop Fires Hit Newly Returned Iraqis Hard,” New Humanitarian, July 8, 2019, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2019/07/08/crop-fires-sinjar-newly-returned-iraqis; and Ahmed Aboulenein and Maha El Dahan, “After Years of War and Drought, Iraq’s Bumper Crop Is Burning,” Reuters, June 20, 2019. ↩

- The ashes from burnt fields were collected by Simon Butler, founder of Migrate Art, and turned into paint by Jackson’s Art Supplies. See “Scorched Earth,” Migrate Art: Art to Aid. ↩

- I am thankful to Mona Hatoum and her studio for providing helpful information about this work. ↩

- Although the 2003 invasion of Iraq has become an iconic moment in recent history, owing to strong opposition from people all around the world and its horrific consequences, Richard McCutcheon has argued that the United States had actually been deploying physical, economic, and cultural violence in Iraq since 1991. Theoretically informed, his analysis is also refreshingly attentive to the lived experience of people on the ground. McCutcheon, “Rethinking the War against Iraq,” Anthropologica 48, no. 1 (2006): 11–28. ↩

- Several observers have written about the implications of the 2003 invasion. See, for example: Howard LaFranchi, “How the Iraq War Has Changed America,” Christian Science Monitor, December 10, 2011; Ian Black, “Iraq War Still Casts a Long Shadow over a Dangerous and Deeply Unstable Region,” Guardian, July 7, 2016; and Tallha Abdulrazaq, “Invasion of Iraq: The Original Sin of the 21st Century,” Aljazeera, March 20, 2018. ↩

- The authors of a report prepared for the United States Air Force by the American think tank RAND referred to an “Iraq effect” to explain the impact of the 2003 invasion, warning of regional consequences to “the stability of pro-U.S. regimes, terrorism, and Iranian power, to name a few,” and adding, “Regardless of the outcome in Iraq, the ongoing conflict has shaped the surrounding strategic landscape in ways that are likely to be felt for decades to come.” The report asserted that the “balance sheet of these changes does not bode well for long-term U.S. objectives in the Middle East.” See Frederic Wehrey, Dalia Dassa Kaye, Jessica Watkins, Jeffrey Martini, and Robert A. Guffey, The Iraq Effect: The Middle East after the Iraq War (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2010, iii, xi). ↩

- Mbembe articulates a similar sentiment, leveling a critique against the notion that war can be fought elsewhere: “Owing to this structural proximity (of the “Other”), there is no longer any ‘outside’ that might be opposed to an ‘inside’… One cannot ‘sanctuarize’ one’s own home by fomenting chaos and death far away, in the homes of others. Sooner or later, one will reap at home what one has sown abroad.” See: Mbembe, Necropolitics, 40. ↩

- In several samples, concentrations of heavy metals were found to be multiple times those of acceptable US standards. These studies have focused on the adverse effects of air pollution on US soldiers deployed in Iraq, who have reportedly experienced more respiratory problems than in other locations. See Rachel Ehrenberg, “Not Even Breathing Is Safe in Iraq,” Wired, March 31, 2011. ↩

- Some research about the environmental and health impacts of war in Iraq has been conducted by Iraqi researchers and is summarized in Ahmed Majeed Al-Shammari, “Environmental Pollutions Associated to Conflicts in Iraq and Related Health Problems,” Reviews on Environmental Health 31, no. 2 (2016): 245–50. ↩

- It is reported that 320 tons of depleted uranium munitions were used in the Gulf War, while nearly 2,000 tons were deployed in the 2003 invasion. See Owen Dyer, “WHO Suppressed Evidence on Effects of Depleted Uranium, Expert Says,” British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition) 333, no. 7576 (November 11, 2006): 990. ↩

- Iraq has been hardest hit but is not the only country in the region to experience extreme temperatures recently. See Falih Hassan and Elian Peltier, “Scorching Temperatures Bake Middle East amid Eid al-Adha Celebrations,” New York Times, July 31, 2020 ↩

- There is local consensus on an issue only occasionally acknowledged by foreign observers: that the rising temperatures are due to the eradication of the green lands at the center of the country—destroyed by American and Iraqi forces to prevent insurgents from hiding in the undergrowth, accompanied by uncontrolled urban sprawl. See Louisa Loveluck and Chris Mooney, “Baghdad’s Record Heat Offers Glimpse of World’s Climate Change Future,” Washington Post, August 12, 2020. ↩

- See Agence France-Presse, “Iraq’s Cultivated Areas Reduced by Half as Drought Tightens Grip,” National, August 5, 2018. ↩

- In a report by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), water flow in many rivers in Iraq is said to have dwindled to about 40%, and Iraq is now facing one of the direst shortages in decades. See Kieran Cooke, “Iraq’s Climate Stresses Are Set to Worsen,” UNDRR: PreventionWeb, November 12, 2018, https://www.preventionweb.net/news/view/61850. ↩

- An unprecedented climate-change study conducted across Arab countries predicts that the impact will vary depending on geographic location and the ability of specific contexts to adapt to evolving conditions. See United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) et al., Arab Climate Change Assessment Report: Main Report, E/ESCWA/SDPD/2017/RICCAR/Report (Beirut: ESCWA, 2017). ↩

- I am grateful to Abbas Akhavan for sharing insights about this work. ↩

- Between 2003 and 2006, it is estimated that there were more than 650,000 excess deaths (an increase in mortality in the Iraqi population beyond the norm) attributed primarily to postinvasion violence. It is believed that 31% of these were perpetrated by the US-led forces, while the rest were caused by related, though indirect and sometimes unknown, causes. See G. Burnham, R. Lafta, S. Doocy, and L. Roberts, “Mortality after the 2003 Invasion of Iraq: A Cross-Sectional Cluster Sample Survey,” Lancet 368, no. 9545 (October 21, 2006): 1421–28. Another survey suggests the actual number is closer to one million; see Luke Baker, “Iraq Conflict Has Killed a Million Iraqis: Survey,” Reuters, January 30, 2008. A conservative but controversial estimate proposed that around 180,000 Iraqis have been killed since 2003 (up to 2013). See Conflict Casualties Monitor, “Total Violent Deaths Including Combatants, 2003–2013,” Iraq Body Count, December 31, 2013. ↩

- 34. There are also approximately three hundred thousand refugees from neighboring countries, the majority of whom were escaping the conflict in Syria. See United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Iraq Refugee Crisis,” USA for UNHCR. ↩

- I am grateful to Thomas Hirschhorn and his studio for responding to a series of questions about this work. ↩

- This version of the quote is printed in the following article, criticizing Rumsfeld’s bending of the truth to justify the ill-fated invasion of Iraq: Roger Cohen, “Rumsfeld Is Correct: The Truth Will Get Out,” New York Times, June 7, 2006. Hirschhorn’s slightly different version, “Death has the tendency to encourage a depressing view of war,” has often accompanied his work Touching Reality, and appears in Hirschhorn, “Why Is It Important—Today—to Show and Look at Images of Destroyed Human Bodies?,” Thomas Hirschhorn, 2012. ↩

- I am thankful for several conversations with Shona Illingworth, which afforded me a better understanding of this complex work. ↩

- Timothy Mitchell argues that fossil fuels, especially oil, have created the conditions for the emergence of modern democracy. He suggests that Iraq, specifically, has been the most critical site for an important historical development of modern democracy, when Western societies attempted an imperial control of the raw materials needed for the prosperity of their democracies. Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil (London: Verso, 2013). ↩

- Companies like BP, Shell, and ExxonMobil are now taking advantage of long-term contracts, which became possible only after favorable conditions were imposed by the US on the post-2003 Iraqi authorities. See Antonia Juhasz, “Why the War in Iraq Was Fought for Big Oil,” CNN, April 15, 2013. ↩

- American and Iraqi politicians used this project to showcase post-2003 positive developments, resulting in foreign firms winning major contracts to secure access to oil, water, and other natural resources. See Bridget Guarasci, “Environmental Rehabilitation and Global Profiteering in Wartime Iraq,” Costs of War project, Watson Institute, Brown University, April 23, 2017. ↩

- The US Department of Defense is the world’s largest institutional consumer of oil. Its emissions dwarf those of many countries. See Neta C. Crawford, “Pentagon Fuel Use, Climate Change, and the Costs of War,” Costs of War project, Watson Institute, Brown University, November 13, 2019. ↩

- In 2005, the US Department of Defense ranked twenty-fourth in global oil consumption, ahead of Sweden and just behind Iraq. See Gregory J. Lengyel, “Department of Defense Energy Strategy: Teaching an Old Dog New Tricks,” 21st Century Defense Initiative, Foreign Policy Studies, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC (August 2007), 6–57. ↩

- Terms like “climate change” are far from neutral—scholars are pointing out that while it may appear to describe a passive and inevitable phenomenon, it stands for a catastrophic fate for humanity: a “climate breakdown,” which goes far beyond weather. See Demos, Scott, and Banerjee, Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art. ↩

- While much media and scientific attention has concentrated on the war’s mental-health impact for American soldiers, the mental-health crisis confronting Iraq today is a major emergency. See Jennifer Percy, “How Does the Human Soul Survive Atrocity?,” New York Times Magazine, November 3, 2019; Omar Mahmoud, “Iraq: Healing the Psychological and Emotional Scars of the Conflict,” Médecins Sans Frontières, October 8, 2017; and Orkideh Behrouzan, “The Psychological Impact of the Iraq War,” Foreign Policy, April 23, 2013. ↩

- I am fortunate to have followed the evolution of this work since its inception, and I am grateful to Ali Eyal, who shared the intentions behind his work. ↩

- Grove argues that the focus on climate change, highlighted as a collective crisis, erases the culpability of the US, and formerly Europe, in creating the current world order, including vast environmental degradation everywhere. Grove, Savage Ecology. ↩

- Many remain unaware of the impact of warfare. Although the term “war” has been used as a metaphor connoting the destruction of the natural world, global militarization tends to be omitted in the media. For example, a harsh warning by António Guterres, secretary-general of the United Nations, presented a wide array of environmental problems, suggesting common responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions while failing to mention the role played by the superpowers’ militaries. See Fiona Harvey, “Humanity Is Waging War on Nature, Says UN Secretary General,” Guardian, December 2, 2020. ↩