This review appears in the Summer 2023 issue of Art Journal.

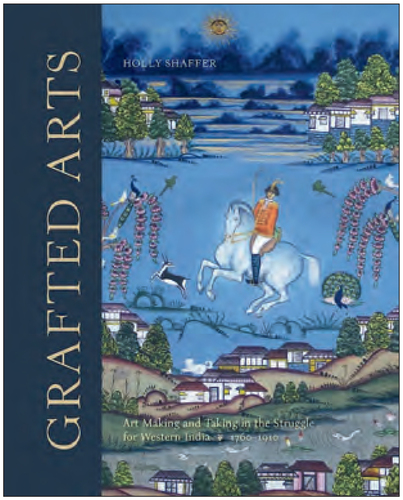

Holly Shaffer, Grafted Arts: Art Making and Taking in the Struggle for Western India, 1760–1910, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022, 320 pp, 150 color + b/w illus; $55.00

In the 1790s in western India, Cowasjee (dates unknown), a Maratha bullock driver employed by the British East India Company, was subjected to a gruesome punishment. The army of Tipu Sultan (1751–1799) captured him during a skirmish in the Third Anglo-Mysore War and hacked off his nose, along with one of his hands—an unequivocal admonition to the ruler’s enemies. Over a year later, a Maratha surgeon fashioned Cowasjee a new nose out of wax, expertly sliced a sliver of skin from his forehead, laid it precisely over the model, and grafted it onto his face. An etched portrait by Company draftsman Robert Mabon (d. 1798) (after a now-lost painting by British artist James Wales [1747–1795]) poignantly immortalized the result of the reconstructive surgery, with an accompanying detailed description of the procedure that claimed it was “not uncommon in India and practiced from time immemorial.”1

Holly Shaffer eloquently opens with this anecdote related to Cowasjee’s eighteenth-century rhinoplasty to introduce the reader to her conceptualization of “graft,” an evocative metaphor that stitches together the five chapters of the cogent Grafted Arts: Art Making and Taking in the Struggle for Western India, 1760–1910. The Marathi word kalam, she elucidates, is rife with meaning, simultaneously translatable as an artist’s tool, the severing of a body part, or the act of grafting in the botanical or medical sense—be it the fusing of a living bud to a tree or fresh skin to heal a wound. “The multiple parts of this definition should give us pause,” she writes, “they connect the means of bringing a picture into being with the forceful processes of excision and suture” (1). In Shaffer’s study, graft and kalam become a theoretical framework to parse the continually shifting and often violent relationship between Maratha military rulers and British East India Company officials, as well as the resultant artistic productions. Her measured prose underscores the mercenary nature of these exchanges, staying clear of the euphemisms and romanticized tropes that often permeate writing on the period. The dynamic’s generative, albeit asymmetric, nature is key: “To graft is a method of creation as much as it is one of taking. It is a process of production and collection as well as a relationship between a foreign body and a host that illuminates the political and artistic circumstances in western India in this period” (1–2).

A comprehensive study of the patronage, production, and circulation of the art of Maharashtra is long overdue. The region has been doubly marginalized and largely overlooked in the historiographies of both South Asian and British art. Grafted Arts is a significant early step towards filling these lacunae, which Shaffer suggests stem from an art-historical aversion to Maratha art’s unclassifiable “hybridity” as well as the fragmentary nature of surviving records and objects, several of which have been destroyed or dispersed across the globe (7). Indeed, one of the volume’s many strengths is the dexterity with which the author contends with these archival gaps while acknowledging the political and institutional structures that shape the surviving records. Far from attempting to conceal the fissures, Shaffer allows the seams to show, persuasively weaving these histories of instability, fracture, and loss into her narrative. Another contribution of the study is the sheer breadth of regional, national, and international archives, usually analyzed independently, but brought into dialogue here. The result is a rigorous exploration of the arts of the region—one that zigzags effortlessly between Marathi and English sources, autobiographies and gazetteers, objects, and their networks of circulation. In addition, the richly illustrated volume includes several infrequently or never-published images from private and lesser-known collections across three continents, presenting a rich corpus of new material for further study.

Shaffer’s narrative begins by charting the genesis of the Maratha aesthetic vocabulary at the Poona court. Comprehensive in scope and scale, the transcultural study moves from the Maratha grafting of British arts to fashion a distinct visual idiom, to the exchange between the two sets of artists, and, finally, to the British grafting of Maratha arts in India and their impact on cultural production in the metropole. Each chapter also centers on one of several interconnected themes—from patron to artist, and from the acquisition of objects to their eventual reformulation (16).

Situating the reader in the latter half of the eighteenth century, the first chapter begins by exploring networks of patronage at the Poona court, focusing on the personal collection built by the powerful Maratha minister, Nana Fadnavis (1742–1800). Shaffer deploys excerpts from Fadnavis’s 1761 autobiography to argue that the statesman harbored an early penchant for amassing objects and that his acquisition practices were formulated by a combination of military force and diplomatic negotiation. We learn, for example, that a young Fadnavis “often stole the household images of the family … and carried them away to some secret place”; years later, enamored by a set of paintings owned by a neighboring family, he ordered his soldiers to “take all of them” (19). Arguing that the diverse works that the minister collected and commissioned through his career shaped a political iconography for the Poona court, Shaffer examines the murals of Hindu deities that covered the walls of his two-story wada (mansion) in Menavali, the networks of artists from Jaipur that he sponsored, and the albums of high-quality Mughal and Jaipur paintings—especially those depicting devotional scenes—that he assembled into albums. The second part of the chapter turns to the work of Sabaji Anant (dates unknown) at the Poona court and James Wales at the British Residency. Shaffer’s study of the British artist is significantly more comprehensive, primarily, she notes, because his drawings, paintings, and personal papers are still extant. Far fewer traces of Sabaji’s existence survive—a reminder of the archival limitations that often hinder attempts to move away from Eurocentric narratives of the period.

This imbalance is remedied in the next chapter, which introduces Gangaram Tambat (dates unknown), an artist from Poona employed by the East India Company. Nominally made in service of the colonial project of knowledge acquisition, Gangaram’s architectural drawings, watercolors, and sculptures document vignettes of life in western India. His eclectic body of work—spanning the Maratha’s ruler’s expansive menagerie, the intertwined bodies of sinewy jethis (wrestlers) at the court, and painstakingly delineated rock-cut temples in the region—was not only shaped by but also shaped European modes of artistic production. Through a series of detailed, formal comparisons that address distinctive approaches to framing, spatiality, shading, and the picturesque, Shaffer convincingly argues that Gangaram’s innovative approach altered how Company ambassador Charles Malet (1752–1815) and James Wales interpreted and represented the world around them while simultaneously incorporating the technical and visual vocabulary that his patrons necessitated. This rethinking of the relationships between British and Indian artists is a key contribution to the growing body of literature by scholars who seek to redefine the parameters of “Company” painting,2 a term coined by art historian Mildred Archer (1911–2005). Archer writes: “Stimulated … by apprenticeship to Company servants, the deliberate copying of British originals, the study of prints and water-colours, and even by direct instruction, Indian artists began to modify their traditional techniques in a British direction.”3 Through the second chapter, Shaffer challenges this notion of a unidirectional “influence,” and demonstrates that both sets of artists engaged with the “Company” manner of making. The Company style might be reappraised, she proposes, “as one of manner rather than identity” (70).

Chapter 3 maps the collection and circulation of religious arts across western India, demonstrating how shifting military dynamics between British and Maratha soldiers—both “on their routes of conquest during war and at their military posts during peace”—spawned four distinct markets: in iconic sculptures of deities associated with pilgrimage sites, war booty seized from forts and palaces, fine paintings, and devotional paintings (132). Shaffer centers her study on Edward Moor (1771–1848), a British soldier who amassed over 360 sculptures and 240 paintings while stationed in India—an assemblage that, she notes, was unique because it encompassed popular regional arts and documented them within Anglo-Maratha martial and collecting practices, establishing a clear provenance. The “graft” leitmotif with its manifold meanings continues to serve Shaffer’s argument well, here alluding to the “corruption and illicit gain” implicit in Moor’s aggressive acquisition of Hindu devotional objects (134). The chapter emphasizes the integral role played by the mechanisms of war in enabling British collecting practices—a welcome corrective to the scholastic tendency to frame the acquisitions of the period as motivated primarily by antiquarian impulses. Shaffer balances a rigorous exploration of these broader issues with an engaging object-centric approach; two richly illustrated sections that detail the creation and circulation of popular Hindu devotional paintings are especially compelling.

The fourth chapter continues with Moor’s collection, which, together with the iconic devotional sculpture amassed by his compatriots, formed the basis of his magnum opus, The Hindu Pantheon. Published with the express intent of cataloging and classifying the Hindu gods, the 451-page compendium was composed of 105 engraved plates with over 300 detailed illustrations of pan-Indic deities. Shaffer suggests that two key features differentiate Moor’s endeavor from the illustrated manuscripts describing the iconographies of Hindu gods that were already in circulation between Europe and India in the eighteenth century. First, he explicitly articulated the relationship between the images and theological texts translated and disseminated among Orientalist networks. Second, the compilation “reformulated” western Indian objects into the aesthetic of the Greco-Roman pantheon legible to a British readership, drawing upon a neoclassical visual vocabulary encompassing a distinctive approach to perspective, modeling, and simplified iconography (177–78,185). Pinpointing these attributes in her detailed study of the gray wash drawings that formed the basis for the engravings of Royal Academy–trained draughtsman Moses Haughton (1773–1849), Shaffer elucidates the philosophical, pedagogical, and artistic reasons for Moor’s use of spare outline, a choice she suggests situated the tome within a broader range of eighteen-century publications that engaged with the classical world (196). In the second half of the chapter Shaffer addresses two paradoxical reuses of this “grafting” of Indian arts onto British ones: as a source of inspiration to visionary artists like William Blake (1757–1827), who repurposed images of the Hindu goddess Durga in the animation of mythical figures in his Jerusalem plates to imagine an anti-tyrannical British history; and as a tool for Christian missionaries, who used the decontextualized engravings in their publications that lobbied for conversions in the subcontinent.

In the fifth and final chapter, Shaffer ties together the diverse eighteenth-century visual arts explored in Grafted Arts, charting their collection and dissemination by the nineteenth-century Indian nationalists who adapted them “to foment discord as well as revolution” against the colonial administration (17). They did so in part by establishing the Chitrashala Press, which produced and circulated inexpensive, mass-produced prints that lionized the Maratha past and deified its political icons with the aim of stoking burgeoning regional patriotism. Shaffer makes the tantalizingly brief suggestion that these images “remain instigators of nationalist agitation today” and, later, that “contemporary politicians reframe them to support a Hindu conception of the nation” (10, 249). She leaves this intriguing thread largely unexplored—the relationship of these illustrations to modern-day communalism is an issue brimming with potential for future scholars to develop. Moving forward in time, the chapter concludes with a compelling meditation on the author’s research methodologies, woven together with her dialogue with contemporary artist Dayanita Singh (b. 1961), whose decades-long practice engages with archives, memory, and the writing of history in the subcontinent. The result of their intellectual exchange is a cross-disciplinary, multi-temporal narrative that sheds new light on the art and history of western India.

Grafted Arts is an invaluable addition to the growing body of literature that foregrounds the artistic production of regional centers of eighteenth-century India beyond the much-studied Mughal court.4 Shaffer’s critical yet accessible research lends itself well to university-level Indian art courses, which, due to a paucity of scholarship, inevitably disregard Maratha art from the period. The author’s self-reflective approach to the historical records, objects, and sites in her study reminds the reader of the deeply entrenched imperial hegemonies that shaped them. This approach simultaneously highlights the responsibilities of scholars of both British and South Asian art history to think beyond English-language sources filed away in museums and archives in the Global North and write new and infinitely more complex narratives. An exemplar in decentralizing the metropolitan archive, Shaffer’s richly layered study effectively resituates western India as a center from which to write the history of the taking, breaking, and re-making of goods between Britain and India.

Tara Kuruvilla is a PhD candidate at the Department of Art History & Archaeology, Columbia University. She is currently the collections research preceptor at the Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago.

- Robert Mabon after James Wales, Cowasjee (Göttingen State and University Library, Göttingen, 1794). Etching, printed in Bombay by James Wales. Reproduced in Holly Shaffer, Grafted Arts: Art Making and Taking in the Struggle for Western India, 1760–1910 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022). ↩

- For a critical reevaluation of the term, see: William Dalrymple and Yuthika Sharma, eds., Painters and Princes in Mughal Delhi, 1707–1857 (New York and New Haven, CT: Asia Society Museum and Yale University Press, 2012); Yuthika Sharma, “Art in between Empires: Visual Culture and Artistic Knowledge in Late Mughal Delhi, 1748–1857” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2013); Marta Becherini, “Staging the Foreign: Niccolò Manucci (1638–ca.1720) and Early Modern European Collections of Indian Paintings,” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2013); Chanchal B. Dadlani, From Stone to Paper: Architecture as History in the Late Mughal Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018); Sita Reddy, “Ars Botanica: Refiguring the Botanical Art Archive,” Marg, A Magazine of the Arts, 70, no. 2 (December 2018); William Dalrymple, ed., Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company (London: Wallace Collection, 2019). Most recently, the Yale Center for British Art’s upcoming exhibition, Company Painting: Artists and the British East India Company, 1760–1830, positions itself as “the first to challenge and critically rethink the phrase’s racialized underpinnings.” ↩

- Mildred Archer, Company Drawings in the India Office Library (London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1972), 6–7. ↩

- Chanchal Dadlani and Holly Shaffer, “The Mughals, the Marathas, and the Refracted Long Eighteenth Century: A Dialogue,” Journal18 12 (Fall 2021). ↩