This article appears in Art Journal, vol. 82, no. 4 (Winter 2023).

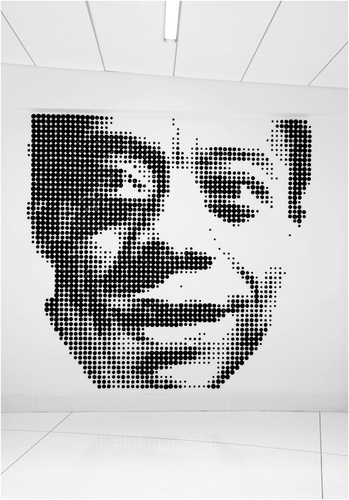

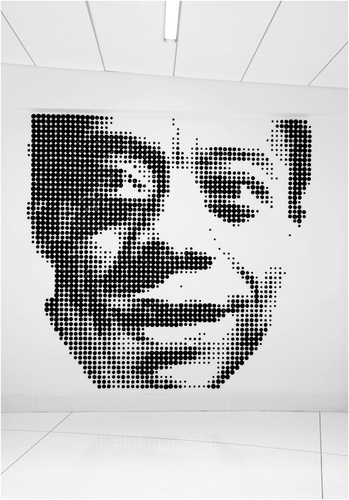

The unmistakable countenance of James Baldwin appears in dissonant tone, as clay, pigment and light ruse pictorial formation. The matte white background collocates with the glint of hundreds of black pigmented hemispheres, each faithfully but intermittently forming the constellation of a grid. From afar, material emerges portraiture: the distinct face of a black queer literary figure, whose eyes look left, missing the viewer’s gaze completely and settling on something else entirely, his smirk perhaps evidencing the pleasure of what he holds in view.1 Up close, however, image stagnates and recontours into nothing more than three-dimensional dots, whose obscured asymmetrical facets reflect the movement of light. This cryptic movement is further emphasized when viewed through the lens of a camera, which compresses the polymer clay mounds into exacting lines that sharpen the features of the figure. DC-based artist Nekisha Durrett (b. 1976) designed this installation, aptly entitled James Baldwin (2018), to take on a third surface when visualized up close through a digital aperture. At the opening of the National Portrait Gallery’s fifth triennial Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition Exhibition American Portraiture Today (2019), the artist stands in front of her installation encouraging viewers to hold their phones up to the image and wait for something unexpected to happen. The unexpected is subtle, divergent from technology’s presumed exaggerating effects. Instead, the camera warps space and troubles tactility, mimicking what viewers would see from a distance. This speculative play with texture, space, and optical effects beckons the question, if only a subquestion: Is the installation James Baldwin vicinal to the perceptional experience of the art world’s sidelined and forgotten framework Op art?

In this article, I take up this question as a polemic rather than an examination and position black op art as an aesthetic lens and method that reckons with what black contemporary artists are doing in the face of institutional dispossessions. For both Durrett and Berkeley, California–based, multimedia artist Lava Thomas (b. 1958), dispossession is far more faceted than the binary edges of inclusion or exclusion from art institutions. Instead, their presence within the National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, respectively, further saturates the knotty politics of dispossession in the art world. As Angie Morrill, Eve Tuck, and the Super Futures Haunt Collective remind, while dispossession “attends to how human lives and bodies matter and don’t matter—through settler colonialism, chattel slavery, apartheid, making extra-legal, immoral, alienated.”2 In the multifaceted spaces and dynamics of art institutions, dispossession also attends to erasure, neglect, forgetting or failing to archive, and misinterpreting or misreading a work of art due to botched attempts to consider intersectional axes of oppression, such as racism, sexism, transphobia, fatphobia, xenophobia, ableism, and queerphobia. Thinking with dispossession, in other words, brings to attention modes of mattering for black artists within systems that insist otherwise.3 Broadly, I argue the term black op art reveals how artists are centralizing speculative sensory effects as both object and subject within their work and therefore as dynamic interventions within the political, hyperracialized, and dispossessing field of visuality. Black op art is neither about what is knowable nor enigmatic through the visual field, but rather about what lengths artists must go to in order to work within it, as well as the ciphered language of mattering and meanings embedded within works of art. Specifically, I consider dispossession through a studied meditation of two works that similarly play and push on the edges of optical effects: James Baldwin by Nekisha Durrett and Requiem for Charleston (2016) by Lava Thomas, which both foreground black op art as a soft murmur of aesthetic “undertones” that refuse optical coherence and determinacy.4

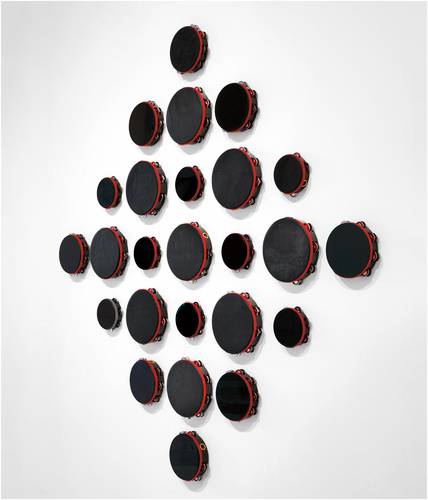

Lava Thomas’s Requiem for Charleston confuses space, as the interplay of wall and tambourines refuse the clarity of periphery.5 Instead, the limits of this multipiece installation recede rather than end at material’s edge, where wall weaves in-between circular forms without closure. From a distance, the installation reveals twenty-five unframed tambourines forming a “square turned on its side so the axis of the piece form a cross” in the former contemporary wing of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. At the center, a large tambourine covered in black lambskin appears gray-toned and matte; the indentations of burnt calligraphic letters gleam into recognition a name: the Reverend Clementa C. Pinckney. Around it, four smaller tambourines anchor inches away on the wall, forming the points of a simple diamond formation—covered in black acrylic discs, their heads sharply reflect anything within proximity, representing faces, objects, and space alike. The next layer comprises nine large tambourines arranged in a three-by-three diamond formation. Both the size and material match the light-absorbing surface of the central tambourine, differing only in the names tenderly inscribed: the Reverend Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, Cynthia Graham Hurd, Susie Jackson, Ethel Lee Lance, the Reverend Depayne Middleton-Doctor, Tywanza Sanders, the Reverend Daniel Simmons Sr., and Myra Thompson. The final rung of tambourines is made up of contrasting sizes but repeats the reflective acrylic of interior pieces, further mirroring light and space and holding each transcribed name in a structure of deliberate reflection: a requiem for the Charleston Nine.6

I want to state early that these two works matter to me.7 I was struck by the traditional Op art effects evident in both installations and curious why art critics did not prioritize the language of this movement. While a visual analysis that singularly prioritized traditional Op art would have also failed in thinking with these installations, I questioned whether it was better or worse than a censored and vague autobiographical account of Baldwin, for example, and a short but thoughtful statement on the nine black people murdered in 2015 at the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. In both installations, the dispossession is clear. The circulation of both works of art have been dispossessed from their performances of Op art as a traditional art historical movement—and therefore from the social and economic power obtained by such aesthetic legibility; and second, from black aesthetic forms, side-glanced for the more obvious but otherwise delimited tropes of figuration and abstraction produced by the representation of Baldwin and black death, respectively.

In this article, I look to better understand the layers of dispossession that the pairing of Op art and black aesthetic forms reveals. Dispossession in both Durrett’s and Thomas’s installations renders a new set of terms and questions about the role of optics and blackness in the art world. I engage traditional Op art as a peripheral reference and archive the movement as a footnote or ephemeral question to the methods, visual proclivities, and sensory landscapes positioned by the artists of this new aesthetic frame. This theoretical intervention aligns with scholars such as Michelle Wallace, Thelma Golden, and Huey Copeland, who elsewhere caution of the quick erasure of the “messy entanglements of blackness” when bidding to “preserve the sanctity of hegemonic aesthetic categories” within the art world.8 My aim is not to preserve or enliven the forgotten contours of Op art but to take seriously what it means when artists coalesce multiple modes of dispossessed materiality. In other words, this pairing is of particular interest because of the optical and social negation already wrapped into the history of Op art. Something specific happens at this intersection that is not activated when black artists work within traditional art movements that are celebrated, remembered, and hyperlegible. This article resists and in fact refuses lineal relations between Op art and black op art. Instead, I foreground optically potent modes, methods, and possibilities within dispossession as fortold by Durrett and Thomas as organizing concepts of black op art.

Contemporary reevaluations of Op art frequently attempt to rescue the lost movement from obscurity by carefully intellectualizing the sensationalism originally attributed to the aesthetic approach. The 2019 exhibition Vertigo: Op Art and A History of Deception, 1520–1970 initiated by the Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien in Vienna, Austria, for example, opens its more than 200-page catalog with such a statement of presumed deliverance. “Long devalued as a superficially sensational phenomenon lacking in intellectual depth,” curator Eva Badura-Triska writes, “Op Art, on closer inspection, proves to be an extremely complex movement that occupies an essential position in the history of twentieth century art.”9 Further, in her recovery text, she takes extreme lyrical care to foreground what critics and viewers alike found fascinating about the movement, calling attention to sensation and the way artists used formal arrangements to impact space and by extension viewers. She writes, “The dizzying maelstrom of spirals, super-imposed and distorted grids, which create moirés and other vibrating patterns, and sensations of toppling, vexation, or flickering are just some of the formal means that this particular abstract art deploys in its painting (kinetic) objects, experiential spaces, and films. They produce strong stimuli that affect the entire body of each recipient, extending far beyond the sense of sight, and function as strategies of sensory irritation, overload, and deception. In the immediate reception of these works, reflection is initially held back in order to then generate an awareness of the shortcomings and constrained scope of perception and cognition rooted in the senses. Radical significant insights are thus triggered in a direct sensory mode.”

However, rather than bidding for hierarchical power and placement in the art world, I am far more fascinated by the way Op art has been devalued in the history of contemporary art movements.

Op art came into the public consciousness in October 1964 through a Time magazine preview article entitled “Op Art: Pictures That Attack the Eye,” written to prepare and enliven museum goers for the soon to open exhibition The Responsive Eye, curated by William C. Seitz at the Museum of Modern Art.10 “Preying and playing on the fallibility in vision,” critic Jon Borgzinner principles, “is the new movement of ‘optical art’ that has sprung up across the Western world. No less a break from abstract expressionism than pop art, op art is made tantalizing, eye-teasing, even eye-smarting by visual researchers using all the ingredients of an optometrist’s nightmare.”11 Even as Borgzinner historicized the new aesthetic frame in the 1960s, highlighting its “legitimate ancestry” in “Cezanne, Seurat and Monet,” as well as its contemporary influences found from Italy to Venezuela, he concurrently foreshadowed its inevitable disinheritance by the art world. For example, Carl J. Weinhardt Jr., director of Manhattan’s Gallery of Modern Art, is quoted using sexist and femmephobic language to underscore his refusal to invest in the movement: “Optical art is this year’s dress length and I will not show any.”12 However, regardless of the varied reception of the new art form, what is clear is that Op art would shift attention to the dynamic play between viewer, space, and art object by emphasizing spatial and embodied effects. As Márton Orosz explains, “The discursive space generated between the work and the viewer became the theme of the show.”13

Reflecting on the influence of William C. Seitz and the 1965 exhibition, Dan Cameron, curator of contemporary art, recalls, “Op Art became somewhat of a household word in the U.S., but almost invariably employed in the pejorative as an example of an art movement that wasn’t really a movement at all but merely an eccentric symptom of a befuddled era.”14 In the referenced era, the mid-to-late 1960s and early 1970s, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover would soon be exposed for the sustained and aggressive tactics of infiltration, psychological warfare, harassment, and extralegal violence toward black radical groups and leftist organizing efforts systematically mandated through the state intelligence-gathering agenda known as the Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO). The purpose of COINTELPRO, according to Hoover, was to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit and otherwise neutralize” groups and individuals that threatened the stasis of the preceding decades’ revivals of white supremacy. In addition to being an era of collective uprising from the anticapitalist, antiracist, and antiimperialist work of the Black Panther Party to the occupation of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), also known as the 504 sit-ins, it also further exposed the fused relationship between antiblack violence and the optical field. “It is my contention,” demarks Leigh Raiford in her 2011 book Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare, “that black visuality is inextricable from African American movements’ effort to change the condition of black people’s lives.”15 Or as visual culture scholar Sampada Aranke reasons, “Racialized violence undoubtedly is organized (pan)optically, as the nexus of surveillance and subjection are foundational in everyday Black life. Because of this ubiquity of sight and surveillance in modes of anti-Black violence, the aesthetic practices undertaken by Black artists are born out of an antagonism with such realities.”16 While COINTELPRO was publicly exposed in 1971 when the “Citizens Committee To Investigate the FBI” removed secret files from an FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, and released them to the press, the illegal state sanctions program did not end that year, despite many claims otherwise. Instead, the Reagan Administration in the 1980s actively endorsed, sponsored, and legalized many other secret and illegal policies of previous generation. Put another way, while “Op artists (of the 1960s) resist interpretation . . . by making paintings that resist being seen at all and that, by resisting our efforts to see them, literally move us around the room in the hope of seeing what we cannot,” black op art knows it cannot go unseen.17 Black op art is about the visual language of distortion as a testimony of erasure, surveillance, and hypervisibility.18 The concurrent political moments of COINTELPRO and traditional Op art paint it as a form steeped in whiteness because it insists not only that art can be seen but that this impenetrable norm can be resisted through visual distortions. When we look at artists like Durrett and Thomas, we see optical technologies that insist on something other than the thwarting of vision; instead, through black op each artist plays with the visibility of dispossession appropriated toward fugitivity.

Dialogues of Dispossession

My aim in considering dialogues of dispossession is to call attention to and further question the entailments of social, political, and relational power dynamics entrapped at the crossroads of black aesthetic practices and traditional art historical movements. The lens of black op art is made possible by questions posed by visual culture scholars. For example, in her third book Listening to Images, Tina Campt offers, “My own space-making gesture ruminates on two central questions: how do we build a radical visual archive of the African Diaspora that grapples with the recalcitrant and the disaffected, the unruly and the dispossessed? Through what modalities of perception, encounter and engagement do we constiutute it?”19 Alexandra Schulteheis Moore defines the dispossessed as “those who lack the right to claim rights . . . and whose existence at once illuminates paradoxes at the core of human rights and challenges concepts of their universality.”20 In other words, dispossession confronts concepts of the universal by highlighting and archiving histories of social and material disposability. However, as Morrill, Tuck, and the Super Futures Haunt Collective lyrically insist, “The opposite of dispossession is not possession. It is not accumulation. It is unforgetting. It is mattering.”21 I turn to dispossession as a throughline in black op art in order to foreground the layered and relational power dynamics at play when exhibiting works by black artists. In this way, dispossession acts not just as a noun, naming forced histories of denial and deprivation, but foregrounds the performance of dispossessing, specifically the dispossessing work of institutions, in the present.

C. Riley Snorton and Hentyle Yapp center another paradox of dispossession for black artists in mainstream art institutions in the introduction of Saturation: Race, Art, and the Circulation of Value. Primary of concern in their analysis is the stakes of legibility: “Museums attempt to increase diversity by exhibiting work by and hiring those who have been historically excluded, but we must ask what expectations surround these individuals when they enter an institution. In particular, these subjects often are required to perform and interact in legible ways that are institutionally sanctioned and deemed appropriate.”22 What is particular about the installations James Baldwin and Requiem for Charleston is how both obscured even an obvious association with the art world’s own framework of Op art. Even as they perform aesthetic legibility by way of Op art, their legibility is dispossessed.23

Multidisciplinary sculptor Simone Leigh highlights another aspect of dispossession for black artists within art institutions in an interview with visual culture scholar Uri McMillan and friend and collaborator Chitra Ganesh. “While our exhibitions are not always welcome,” she begins, “the black performing body always is. And the spectacle of it is used to mask the structural racism of art institutions that have repeatedly excluded black artists and their exhibitions.”24 Cheryl Dunye, director, actor, and writer known for evading the limits of aesthetic labels in black and queer documentaries, such as The Watermelon Woman (1996) and Mommy Is Coming (2012), emphasizes another aspect of dispossession for black artists within art institutions. When asked in an interview with art historian and queer and feminist scholar Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Do . . . labels have any meaning to you?,” she responds with an emphatic “yes”: “Labels . . . send signals to audiences and critics that the maker has somehow been deemed worthy of commercial success and visibility. But if that artist continues to create work that challenges commercial sensibilities or challenges what is normative in story or content, they generally end up broke. So yes, labels mean a lot.”25 In other words, labels are about survival, too. However, mattering is not synonymous with visibility. Instead, black op art mediates mattering as politicized attention and care. Visual culture theorist Nicole Fleetwood mirrors the complexities of art criticism for black artists in her 2019 reflection on the reception of John Edmonds’s photography. She writes, “While black artists and other artist of color have had more representation in international biennials and museum shows in recent years, the reception of their art is still often framed by a narrow and rarified cultural perspective.”26 Black op art foregrounds the politics of labels and histories of dispossession that pursue in the art world for black artists. It asks how to create material and political frameworks of mattering in mainstream art institutions without centering white aesthetics and production.

In 2008, the philosopher Fred Moten published an article entitled “Black Op,” where he positions the term “Black Op” alongside theories of dispossession. While his use of the phrase appears only in the title of the article and does not specifically address the role of the artist or histories of art, he does continue the legacy of visual culture theorists who position visuality as a center of the study of blackness. I reference Moten’s tangential use of the term “Black Op” to set a new precedent in the theoretical lineages of black op art as an aesthetic framework. Rather than returning to the history of Op art, theoretical intersections are ascribed within the field of black studies. For Moten, “Black Op” is a cipher for the interrelation of black optics, black object, black optimism, black operation, and the black open, all of which encircle concepts of dispossession. He writes, “What is often overlooked in blackness [read: black object (see p. 1746)] is bound up with what has often been overseen. Certain experiences of being tracked, managed, cornered in seemingly open space are inextricably bound to an aesthetically and politically dangerous supplementarity, and internal exteriority waiting to get out, as if the prodigal’s return were to leaving itself. Black studies’ concern with what it is to own one’s dispossession, to mine what is held in having been possessed, makes it more possible to embrace the underprivilege of being sentenced to the gift on constant escape [read: black open (see p. 1743)] . . . . In contradistinction to the skepticism, one might plan, like Curtis Mayfield, to stay a believer and therefore to avow what might be called a kind of metacritical optimism. Such optimism, black optimism (see pp. 1745–47), is bound up with what it is to claim blackness and the appositional, run-away, phonoptic blackness operation [read: black optics, “an auditory affair” (see p. 1743) and black operation (see p. 1745)]—expressive in the autopoetric organization in which flight and inhabitation modify each other—that have been thrust upon them.”27

Moten positions dispossession as an animacy of black studies, our open secret archiving and further preparing multidirectional escape (“escape in and the possibility of escape from”).28 This black operation is political, bound to racialized discourses of visibility and optical imaginaries activated as tools of oppression. In the next section I will examine how the work of Thomas explores and synthesizes such imaginaries. The gift of black objects, however, is to signify multiple and find such signification outside of the visual realm. Black optics therefore becomes more than dominant looking relations but opens to the multisensorial: “This black optics is an auditory affair: night vision given in and through voices that shadow legitimate discourse from below, breaking its ground up into broken air; scenes rendered otherwise by undertones that are overheard, but barely.”29 In other words, this phonoptic blackness operation is what materializes the sustenance of black optimism that “lives (which is to say, escapes) in the . . . assertion of a right to refuse.”30

I reference Moten to emphasize the resistance to determinacy, which I argue, rests both at the core of black op art and alongside the barely overheard undertones of the work. Thinking with black op is at once speculative, as what the artists are refusing is surely not singular. I argue that a primary tenet of black op art is a subtle undercurrent that repositions attention to systems of dispossession while preserving remnants of what survives despite, through, and because of it. As Moten rallies, “Everything I love is an effect of an already given dispossession and of another dispossession to come. Everything I love survives dispossession, is therefore before dispossession.”31 Following the soft murmur of aesthetic undertones in the work of Durrett and Thomas is a calling toward alternative testimonies of being with the work. In the balance of this article, I follow the flickering methods of black op art to arrive at statements of black mattering(s) scripted within the material and conceptual subtext of each installation.

Part One: Lava Thomas

“When the news broke of the massacre at Mother Emanuel Church,” Thomas shares, “I was working in my studio on another tambourine piece and a series of portraits of my southern ancestors.”32 The day is June 17, 2015. The news cycles that followed would recount the slow intentionality of murders that would take the lives of nine black humans, later to be known as the Charleston Nine. Reverend Sharon Risher, whose mother, two cousins, and a childhood friend were killed at Mother Emanuel Church that day, recounts the moments directly preceding the first shot: “They welcomed him in, Risher says. He sat there and listened to this whole Bible study.”33 As a self-proclaimed white supremacist, the killer strained the media to account for systems and histories of racial terror. Reports of the massacre were identified as an irregular effect of extreme white supremacy—white supremacy made him do it—leveling his actions as a consequence of scarce extremist thinking. However, the repetitive forms in Requiem for Charleston grounds these deaths in an alternative telling: the extralegal murders of the Charleston Nine rehearse systems of racial terror and black death as the substance of white supremacy rather than its consequence.

Lava Thomas, Requiem for Charleston, 2016, close up of Susie Jackson, tambourines, pyrographic calligraphy on lambskin, acrylic discs, and braided trim, dimensions variable. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Nion McEvoy, 2017.4A–Y (artwork © 2016 Lava Thomas; photograph provided by the Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Lava Thomas, Requiem for Charleston, 2016, close up of the Reverend Clementa C. Pinckney, tambourines, pyrographic calligraphy on lambskin, acrylic discs, and braided trim, dimensions variable. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Nion McEvoy, 2017.4A–Y (artwork © 2016 Lava Thomas; photograph provided by the Smithsonian American Art Museum)

As Claudia Rankine’s identifies in her essay, “The Condition of Black Life is One of Mourning,” written on occasion of the 2020 exhibition Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, “[The killer] did not create himself from nothing. He has grown up with the rhetoric and orientation of racism . . .. Every racist statement he has made he could have heard all his life. He, along with the rest of us, has been living with slain black bodies.”34 Bryan Stevenson and the Equal Justice Initiative have meticulously archived the contemporary rise of public spectacle lynching in the United States. Their research rescripts racial killings and massacres from a rogue backlash or fanatic consequence of an otherwise controlled system to the “hypervigilant enforcement of racial hierarchy.”35 Pages after mentioning Emmett Till and Michael Brown, and a moment before addressing the deaths of Tamir Rice, John Crawford III, Eric Gardner, Rekia Boyd, and Aiyana Stanley-Jones, Rankine’s continues, “The truth, as I see it, is that if black [humans] mattered, if we were seen as living, we could not be dying simply because whites don’t like us. Our deaths inside a system of racism existed before we were born.”36 This structurally grounded analysis of antiblack violence sharply contrasts the politics of individualism associated with the Charleston Nine by popular media.

Requiem for Charleston is a statement against the systemic and incessant death of black people, but it is a grief act, too. When the work is distilled through the lens of black op art, we uncover the dispossession encoded in the oscillating reflective surfaces of the tambourines. Thomas gives us an aesthetic language of mattering the dispossessed. In Requiem for Charleston, Thomas teaches us what it means to pause for the repose of souls without getting lost in a rhetoric of individualism. Pausing for the repose of souls asks how and not why. How: a way of reflecting on the repetition of racial terror. Why: a faulty start, make-believing at interest, intercession, and redress. Instead, Thomas translates repose as repetition and makes no attempt to confuse the former with rest.

Connecting repose and repetition through the preposition “as” emphasizes the two as inseparable for black people. These seemingly disparate states of being are connected by Thomas to underline what it means to witness or otherwise live with the repetition of black death. Repose, defined as a state of rest, tranquility, or sleep is impossible within a system built on the deaths of black people. Repose becomes a state of repetition: a repetition of death and a repetition of mourning. By veiling the names of the victims in the soft reflective surface of the lambskin, Thomas makes repose as repetition witnessable by obstructing optical perspicuity and therefore compelling the viewer to move around the gallery and toward the installation in order to read each name. Requiem for Charleston requires a closeness; in order to perceive the handwritten epithets, the viewer must draw close to the work and then step back. For viewers who arrive in mourning, this closeness is a practice of grieving, and the movement a somatic exercise of sorrow. For those who do not, this is another way Thomas refuses repose as a state of rest; instead, the movement required of the installation insists on action, particularly motion that repeats itself—drawing near and around a tambourine and then back out toward a peripheral distance.

Upon moving repetitively through the space, the geometric design of Requiem for Charleston as well as the differently toned and sized circular discs, the sharp contrast of white walls to black tambourines, the differently toned and sized circular formations, and the suspended and floating element of the work all suggest the possibility of a strong afterimage of the installation—all the while manifesting only a subtle if even present poststimulation. However, this installation does not reside in the spectral residue of the visual realm; instead, Requiem for Charleston insists, repose as repetition refuses an afterimage of black violence.

In aesthetic terms, afterimages or “after-effects of stimulation” can be described as “a new pattern interacting with the hangover of the previous pattern”—in other words, stimulated shapes of the same but often contrasting form as the ones directly visible.37 As Barrett notes in her book Op Art, “After-images are a different matter; the artist did not put them there however much [they] may have induced their appearance.”38 Afterimage is called upon in Op art to signify the compulsory optical effects emblematic of the art movement. For example, Badura-Triska explains, “Op Art uses ‘concrete’ artistic means in ways that deny any possibility of contemplative rest not just to the eye and mind but also to the entire body of the recipient.”39 However, afterimages also signify a fatigue. It is a forced embodiment of rest after the receptors of the eye are overstimulated. By citing but not inducing an afterimage, Thomas both refuses rest and the spectral mattering so often equated with the spectacular death of black people. As the Super Futures Haunt Collective states, “the endgame of opposing our dispossession is . . . not haunting, though I’ll do it if I have to; it is mattering.”40 In other words, haunting is labor, too. This type of antiracist work, which Thomas inscribes as plea within this installation, should fall on the viewer rather than the deceased. Requiem for Charleston holds the victims of Mother Emanuel Church in a state of repose that preserves something other than rest and haunting while making visible the repetitive, laborious, and restless state of racial violence—“I chose to leave some of the tambourines blank in memory of the many [people] who’ve died in racial violence against churches throughout history,” the artist shares.41

In The Repeating Body: Slavery’s Visual Resonance in the Contemporary, Kimberly Juanita Brown describes the phenomenon of afterimage as “an ocular residue, a visual duplication as well as an alternation. One could even call it a burning image that eventually fades.”42 The burning that takes place in Requiem for Charleston, however, is not an afterimage or an ocular effect of the installation, but a central material component of the work that does not fade. In a short descriptive video about the installation, Thomas offers a lens into her process: “I inscribed the names of the victims on lambskin using pyrographic calligraphy where I used a burning tool that’s typically used in wood burning crafts and leather crafts to write their names. It was a gesture to burn the names in one’s memory, but also to recall the violence during slavery when enslaved people were branded.”43 In other words, there is no afterimage of black violence. To witness a poststimulatory image, an excess or “ocular residue,” is to draw a line, even in its subtleties, between the event and its effects. To witness an afterimage of the murders at Mother Emanuel Church would suggest a space of rest from the repetition of black death, a distinction between the event and the present moment, a departure, a division. Requiem for Charleston denies an afterimage to deny false claims of racial progress all the while positioning a space of repose for the victims—what could be called a “cartography of dispossession”44—as an offering, a holding, and a prayer.

Thinking with Thomas’s installation through the lens of black op art reveals an undercurrent of repose as repetition that obstructs both rest and haunting. It does not play at redress or anticipate liberation. Instead, Requiem for Charleston is for the victims of the massacre on June 17, 2015; it was made for them and holds them in deliberate attention while reflecting for the viewers what it means to mourn inside a system not made for the survival of black people.

Part Two: Nekisha Durrett

DC-based artist Nekisha Durrett works across mediums to esteem details of the disregarded. Her public art and large-scale installations merge at the point of history, drawing out hidden stories, timelines, and narratives through the subtle and the quotidian. Durrett’s playful and yet decisive articulation of space in James Baldwin follows this charge by subtly rescripting notions of encounter for the viewer. The irregularly edged sculptural elements are positioned to both feign connection and contact and persuade it. In an interview with Durrett, she emphasizes such encounters: “It is only with distance, stepping away from the work, that you can actually take it in and make sense of the image, or you can hold your cell phone up to it while you’re in close proximity and . . . your cell phone [will scale] it down . . . by correcting the resolution. . .. And this is a way you play with space.”45 As referenced in the opening lines of this essay, the scaling down that takes place on the screen of a camera or phone is subtle. It neither transforms the contours of the installation nor adds or subtracts content. Instead, the sharp edges of the polymer clay mounds begin to blur together into crisper lines that transform the face of Baldwin from large, pixilated dots into strokes and shadows that shade the face into near precision. This simulated haptic encounter reveals one of the many ways this installation moves.

Durrett began with a photograph of Baldwin, which she describes as “ordinary.”46 Rather than choosing an image of the author mid-speech or sitting in a pensive stance of activated thinking, she replicates a different version of Baldwin. “It’s just him . . . looking very, very human, very accessible.”47 The process of transforming the anonymously authored photograph into the seven-by-seven-foot installation began by enlarging the portrait and then translating Baldwin’s likeness into a digitized image, with hundreds of halftone dots representing a corresponding sculptural element. James Baldwin is composed of black polymer clay mounds, cast in four strategically sized hemispheric molds. Enlisting her family for support, the artist pressed delicately rolled clay into distinctly sized baking trays and then cast them in kitchen ovens across DC on repeat. Her father’s hands drilled holes in the back of each baked hemisphere, while Durrett transcribed the enlarged digitalized photograph into a cipher, the coded language of numbers—1, 2, 3, 4, 5—distilled in pencil on the seven-by-seven-foot panel that would eventually be mounted on the wall of the National Portrait Gallery. Each recorded number marked the spot of a representatively sized clay mound, which the artist mounted one-by-one with screws, tape, and glue in exacting precision. “If you enter from far away,” the artist shares, “it looks like a work on paper. It looks like a poor reproduction of something blown up . . . and then you get up close and you’re like . . . ‘Whoa, this thing is popping off the wall.’”48 Here the artist’s play on optics is a black op—reaffirming the indeterminacy of the spatial ground of the installation, all the while moving the viewer’s body around the gallery in search of spatial and conceptual discernment.

Nekisha Durrett, James Baldwin, 2018, polymer clay, 84 × 84 in. (213.4 × 213.4 cm), installation views, The Outwin: American Portraiture Today, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC, 2019. Collection of the artist (artwork © Nekisha Durrett; photograph provided by the artist)

Nekisha Durrett, James Baldwin, 2018, polymer clay, 84 × 84 in. (213.4 × 213.4 cm), installation views, The Outwin: American Portraiture Today, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC, 2019. Collection of the artist (artwork © Nekisha Durrett; photograph provided by the artist)

Another moment of encounter can be found in the figuration of James Baldwin. This installation is not an attempt to produce him as a proper subject; instead, taking Baldwin as an object of the installation, Durrett refuses to crystalize the subject of the work, and by doing so, inscribes black op as hidden encounters that happen not just within the installation but also in the ossicular spaces around it. Referencing contemporary photography and lens-centered practices across the African Diaspora, visual culture scholar Krista Thompson details the direction of interventions that we see in James Baldwin. She writes, “it is significant that contemporary photography expressions neither quite allow the photography to materially secure its black subjects nor in some instances permit it to produce widely disseminated photographic records or archives.”49 James Baldwin toys with the limits of photographic representation by beginning with a photograph as impetus and ending with the mediated screen of the unflashed and uncaptured photo display. The halftone hemispheres do not touch through the lens of the camera but perform touch through optical effects of this third surface, reconfiguring the boundaries of tactility. What moves then is not strictly within the gallery space or museum hall but in the betwixt space of the noncapture, the photograph never taken, the speculative and rare nonreproduced moments that was nonetheless witnessed and seen.

This is different than Peggy Phalen’s ontological assertion of performance as present and nonreproducible. Rather than implicating “the real through the presence of living bodies,” the uncapturable and unregulatable is not the installation itself but the popular imaginary of Baldwin as racial icon.50 In fact, Durrett’s numerical cypher and accessible methods of production makes this installation very reproducible (remembering she baked each polymer clay mound in kitchen ovens across DC). However, the third surface of the uncaptured photo moves this imagery— very literally by shrinking spaces and blurring edges of the clay mounds—and in doing so, removes it from a narrative of action. Put another way, Fleetwood reminds us, “Racial icons make us want to do something. These images can impact us with such emotional force that we are compelled to do, to feel, to see.”51 While this is usually the case of Baldwin’s likeness, the noncaptured space of the screen never turned photograph escapes Baldwin from this demand. Instead, nonreproductive and nonconsumptive, this mediated space of the uncaptured photo lurches into the ground that Phalen describes—“disappears into memory . . . and the unconscious where it eludes regulation and control”— and, I add, where it moves without the promise of effect.52 Rather, it becomes something other than the “present.”53 The hovering photograph never taken escapes Baldwin from both the regulated spaces of the future and the past, producing instead an entirely distinct present performance of the installation—one that can be reproduced with any camera or phone, at any moment, but never reproduced exactly the same again.

Another way this installation moves is by way of the viewers’ mediated encounters with James Baldwin through the deliberate lens of portraiture. The spatial distortion of the work by way of the viewers’ phones works in sharp contrast to the gallery’s framing of the installation as situated beneath perfect double arches that evoke an almost sacred architecture of admiration. While the sculpted clay mounds of the work disrupt the bounds of traditional portraiture, walking into the exhibition gallery and immediately being met with the likeness of Baldwin both celebrates portraiture’s visual primacy and lifts him up as a heroic and celebrated black cultural figure. What Durrett is asking us to recognize is not James Baldwin but rather the systems of dispossession that produce him as cultural figure. In this way, Durrett reveals how black op art maneuvers as a method, mapping onto and through other aesthetic frameworks. By reinscribing Baldwin within the same lens that popular culture demonstrates attention—the portrait and the popular—Durrett reflects a polemic of dispossession: what methods do we have to insist upon our mattering? Rather than reinscribing portraiture as a tool of recognition, she relies on black op as a method that surfaces other undertones of mattering and meaning within the work. For example, it is a “secret” that before hanging each hemisphere the artist adorns the sculptural elements with a hologram by applying acrylic spray paint, with an iridescent, clear, high gloss composed of microflex of glitter.54 In the regulated lighting of the museum, the iridescence of the sculpture is imperceptible. However, in sunlight or under the mediated attention of a flashlight or flash, the opalescence of the sculpture surfaces. The refusal of the object to glimmer within the controlled atmosphere of the museum activates one of many undertones within this installation. Black op art repositions attention away from frameworks of legibility as determinate avenues of understanding and instead recenters the interminability of the speculative. For Durrett, the reminder is in the encounter, never exactly the same again.

In the Spring 1987 issue of Culture Critique, Barbara Christian calls into question the rising trend toward theory, beginning her essay with at statement of deliverance: “I have seized this occasion to break the silence among those of us, critics, as we are now called, who have been intimidated, devalued by what I call the race for theory.”55 She continues on to argue for a recalibration of what is and is not considered theory, as well as a more careful delivery of the offerings of the artist. She writes, “For people of color have always theorized—but in forms quite different from the Western form of abstract logic. And I am inclined to say that our theorizing (and I intentionally use the verb rather than the noun) is often in narrative forms, in the stories we create, in riddles and proverbs, in the play with language, since dynamic rather than fixed ideas seem more to our liking. How else have we managed to survive with such spiritedness of the assault on our bodies, social institutions, countries, our very humanity? . . . My folk, in other words, have always been a race for theory—though more in the form of the hieroglyph, a written figure which is both sensual and abstract, both beautiful and communicative. In my own work I try to illuminate and explain these hieroglyphs, which is, I think, an activity quite different from the creating of the hieroglyphs themselves.”56

Black op art is not a theory; it is a lens and a method that changes with each enactment and engagement. It resists, as Christian wrote, the persistent dispossession of both black artists and the “sensual and abstract, both beautiful and communicative” undertones expressive within their work. In this way, black op art refuses a lineage of hegemonic categorization, as well as strict definitional boundaries and limits; instead, it seeks to call into practice what Copeland and Aranke have qualified as a posture. In the concluding paragraphs of “Blackouts and Other Visual Escapes,” Aranke invokes Copeland’s methodological approach entitled “tending-toward-blackness—a leaning into and caring for,” which was formalized by Copeland in his 2014 essay “Unfinished Business as Usual: African American Artists, New York Museums, and the 1990s” and further contextualized in a short article published in issue 156 of October.57 Copeland offers his ambition for thinkers of black art, writing, “Just imagine what might be possible if, instead of rushing to the new, we tended toward blackness—in all of its sensuous and imperceptible unfolding—that phantom site whose traces everywhere mark the construction of the material world and provide a different horizon from which to take our bearings.”58 Aranke builds upon Copeland’s definitional stance, reminding readers: “Blackness is pictured, seen, even felt as relational and active. It is about an aesthetic position that opens up to a set of questions between the figure and ground, subject and object, pictured and seen.”59 Black op art is a vacillating and yet compelling performance of the still promised charge of dispossession for black artists. It reckons with the quiet and yet insistent undertones, “that are overheard, but barely,”60 the subtle or the easily disregarded, the blaring and impossibly overlooked, and asks how those moments, materials, intentions, or aims do something, whether efficacious in their movements or not.61

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Lava Thomas and Nekisha Durrett for the care, time, and labor dedicated to their work. I was grateful to visit these installations often while in residence in DC. I am also grateful for the support of fellows and colleagues at UC Berkeley, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, and the UC President’s Postdoctoral Fellowship who offered emotional and spiritual support as I grappled with the themes of this article, especially Kaia Black, Jess Dorrance, Amelia Goerlitz, Caleb Luna, Ana Perry, Claudia Zapata, and the mentorship of Uri McMillan and E. Carmen Ramos. Thank you also to Saisha Grayson for originally connecting Thomas’s and Durrett’s work for me in conversation so many years ago. My immense gratitude goes out to Rachel Kravetz and Julia Havard for editing and providing tender feedback on drafts of this essay, as well as the Center for African & African American Studies Junior Scholars at Rice University, Amarilys Estrella, Helena Fietz, Victoria Massie, Laura Correa Ochoa, Tamar Sella, and Margarita M. Castromán Soto for your intellectual support, friendship community, and conceptual insights as I developed this article. And lastly to the editors and peer reviewers at Art Journal, your invaluable feedback made this essay better and enlivened me in the process.

Olivia K. Young is an assistant professor in the Department of Art History and the Center of African & African American Studies at Rice University. In 2020, they completed their PhD in the Department of African Diaspora Studies at UC Berkeley. Previously, they were a UC President’s Postdoctoral Fellow and a Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

- I have chosen not to capitalize the word black throughout this publication because I do not cosign contemporary trends to distinguish between different circulation and appropriations of the word or draw it into realms of properness. This stance of properness contradicts black, queer, trans, crip, and radical efforts to critique compulsory pressure toward normativity. La Marr Jurelle Bruce writes, “I use a lowercase b because I want to emphasize an improper blackness: a blackness that is a ‘critique of the proper’; a blackness that is collectivist rather than individualist; a blackness that is ‘never closed and always under construction’; a blackness that is ever-unfurling rather than ridged and fixed; a blackness that is neither capitalized nor propertized via the protocols of Western grammar; a blackness that centers those who are typically regarded as lesser or lower case, as it were; a blackness that amplifies those who are treated as “minor figures’ in Western modernity.” For more, read the introduction to Bruce, How to Go Mad without Losing Your Mind: Madness and Black Radical Creativity, Black Outdoors: Innovations in the Poetics of Study (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 6. ↩

- Angie Morrill, Eve Tuck, and the Super Futures Haunt Collective, “Before Dispossession, or Surviving It,” Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies 12, no. 1 (2016): 5. ↩

- For more on an intersection analysis of black mattering, see the vision statement written by the Harriet Tubman Collective. ↩

- Fred Moten, “Black Op,” Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 123, no. 5 (2008): 1745. See section “Dialogues of Dispossession” in this article for more on the concept of undertones and how I link it to black op art. ↩

- Smithsonian American Art Museum, “Meet the Artist: Lava Thomas on ‘Requiem for Charleston,’” Youtube, November 13, 2017. ↩

- The sonic register is also an important component of this installation. Thomas discusses the tambourine as a protest instrument and an object used within religious ceremonies. I have not addressed sound in this article, but I hope and encourage a longer reflection on Requiem for Charleston, where multisensorial analysis is undertaken with greater breadth and depth. ↩

- I began writing this article in 2019 as one of the few black predoctoral fellows at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. I returned to these two installations often. I am especially thankful to Dr. E. Carmen Ramos, former curator of Latinx art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, for advocating for the acquisition of Requiem for Charleston and the jurors for the fifth triennial Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition Exhibition American Portraiture Today for including James Baldwin in the exhibition: Bryon Kim, Harry Gamboa Jr., Lauren Haynes, Jefferson Pinder, Brandon Brame Fortune, Dorothy Moss, and Taína Caragol. ↩

- Huey Copeland, “One-Dimensional Abstraction,” review of 1971: A Year in the Life of Color, by Darby English,” Art Journal 78, no. 2 (Summer 2019): 116. ↩

- Eva Badura-Triska and Markus Wörgötter, eds., Vertigo: Op Art and a History of Deception, 1520 to 1970 (Cologne: Walther König, 2020), 17. Additionally, the 2017 Palm Springs Art Museum exhibition and subsequent catalog Kinesthesia: Latin American Kinetic Art, 1954–1969 similarly rescues the “close relative” of Kinetic art from obscurity while simultaneously questioning why and how the movement was bifurcated from its Latin American lineage; see Dan Cameron, ed., Kinesthesia: Latin American Kinetic Art, 1954–1969 (Palm Springs, CA: Palm Springs Art Museum; Munich: DelMonico Books/Prestel, 2017). ↩

- Cyril Barrett, Op Art, A Studio Book (New York: Viking Press, 1970), 1. Seitz, who favored the term “New Perceptual Art,” began theorizing the framework of MoMA’s Op Art in 1962, three years before the opening of the exhibition, when he launched an international tour through American and European city centers in search of art that faithfully aligned with the emerging wave of perceptual abstraction. ↩

- Jon Borgzinner, “Op Art: Pictures That Attack the Eye,” Time, October 23, 1964. ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Márton Orosz, “Vasarely and the ‘Op Art’ Phenomenon,” in Victor Vasarely: The Birth of Op Art, ed. Orosz (Madrid: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, 2018), 29. ↩

- Cameron, Kinesthesia, 29. ↩

- Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 27. Raiford continues with an even stronger link between the visual field and black liberation movements. She writes, “Not least of that to be transformed is the individual and collective sense of one’s own power, efficacy, and being in the world; how we see blackness, the meanings we attach to black people, and the value we attach to black life because of this ‘sight’” (27). ↩

- Sampada Aranke, “Blackouts and Other Visual Escapes,” Art Journal 79, no. 4 (December 2020): 66. ↩

- Dave Hickey, “Trying to See What We Can Never Know,” in Optic Nerve: Perceptual Art of the 1960s, by Houston Joe (London: Merrell, 2007), 13. ↩

- For more on the concept of “distortion” as related to contemporary art, see Olivia K. Young’s forthcoming book How the Black Body Bends: Sensorial Distortions in Black Contemporary Art. ↩

- Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 3 (emphasis added). ↩

- Alexandra Schultheis Moore, “‘Dispossession within the Law’: Human Rights and the Ec-Static Subject in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!,” Feminist Formations 28, no. 1 (Spring 2016): 166–67. ↩

- Morrill, Tuck, and the Super Futures Haunt Collective, “Before Dispossession, or Surviving It,” 2. ↩

- C. Riley Snorton and Hentyle Yapp, “‘Sensuous Contemplation’: Thinking Race at Its Saturation Points,” in Saturation: Race, Art, and the Circualtion of Value, ed. Snorton and Yapp (MIT Press, 2020), 2. ↩

- Instead, both Durrett and Thomas achieve legibility through other aesthetic frames with longer histories of black mattering: Durrett by way of portraiture and Thomas through abstraction. In Rankine’s reflection on the Charleston Nine, she makes clear the role of abstraction in processing and grieving the massacre which Thomas cites: “The decision not to release photos of the crime scene in Charleston, perhaps out of deference to the families of the dead, doesn’t forestall our mourning. But in doing so, the bodies that demonstrate all too tragically that “black skin is not a weapon” (as one protest poster read) are turned into an abstraction.” (Rankine, “Condition of Black Life,” 18). This abstraction is echoed by Thomas, who further signals that “visual evidence” of the ocularcentrism of antiblack violence is as much a problem as it is a strategy of resistance. ↩

- Simone Leigh, Chitra Ganesh, and Uri McMillan, “Alternate Structures: Aesthetics, Imagination, and Radical Reciprocity; An Interview with Girl,” ASAP/Journal 2, no. 2 (May 2017): 249. ↩

- Julia Bryan-Wilson and Cheryl Dunye, “Imaginary Archives: A Dialogue,” Art Journal 72, no. 2 (June 2013): 88. ↩

- Nicole R. Fleetwood, “The Quiet Risks of John Edmonds’s Photography,” New York Review of Books, August 30, 2019. ↩

- Moten, “Black Op,” 1745 (I have added emphasis to the use of the aforementioned terms and notated additional references within his essay where further clarity can be gathered). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid.,1743. ↩

- Ibid., 1746. ↩

- Fred Moten. “The Subprime and the Beautiful,” African Identities 11, no. 2 (2013): 237–45, quotation at 242. ↩

- Smithsonian American Art Museum, “Meet the Artist: Lava Thomas on ‘Requiem for Charleston.’” ↩

- Debbie Elliott, “5 Years After Charleston Church Massacre, What Have We Learned?,” National Public Radio, June 17, 2020. ↩

- Rankine, “Condition of Black Life,” 17. ↩

- Equal Justice Initiative, “The Report,” in Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, accessed November 4, 2020. ↩

- Rankine, “Condition of Black Life,” 19. ↩

- Barrett, Op Art, 55. ↩

- Ibid., 56. ↩

- Badura-Triska and Wörgötter, Vertigo, 20. ↩

- Morrill, Tuck, and the Super Futures Haunt Collective, “Before Dispossession, or Surviving It,” 5 (emphasis added). ↩

- Smithsonian American Art Museum, “Meet the Artist: Lava Thomas on ‘Requiem for Charleston.’” ↩

- Kimberly Juanita Brown, The Repeating Body: Slavery’s Visual Resonance in the Contemporary (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 13. ↩

- Smithsonian American Art Museum, “Meet the Artist: Lava Thomas on ‘Requiem for Charleston.’” ↩

- Morrill, Tuck, and the Super Futures Haunt Collective, “Before Dispossession, or Surviving It,” 4. ↩

- Nekisha Durrett, interview by author on Zoom, November 11, 2021. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Krista A. Thompson, Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015). ↩

- Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (London: Routledge, 1993), 148. ↩

- Nicole R. Fleetwood, On Racial Icons: Blackness and the Public Imagination, Pinpoint: Complex Topics, Concise Explanations (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2015), 4. ↩

- Phelan, Unmarked, 148. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Durrett, interview by author. ↩

- Barbara Christian, “The Race for Theory,” Cultural Critique 6 (Spring 1987): 51. ↩

- Ibid., 52. ↩

- Aranke, “Blackouts and Other Visual Escapes”; Huey Copeland, “Unfinished Business as Usual: African American Artists, New York Musuems, and the 1990s,” in Come as You Are: Art of the 1990s, ed. Alexandra Schwartz (Montclair, NJ: Montclair Art Museum; Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), 25–32; and Copeland, “Tending-toward-Blackness,” October 156 (Spring 2016): 141–44. ↩

- Copeland, “Tending-toward-Blackness,” 144. ↩

- Aranke, “Blackouts and Other Visual Escapes,” 75. ↩

- Moten, “Black Op,” 1743. ↩

- Campt, Listening to Images. For more on theories of “quiet,” see Campt, “Introduction: Listening to Images; An Execise in Counterintuition,” in ibid., 1–12. ↩