This article first appeared in Art Journal vol. 83, no. 2 (Summer 2024)

Contemporary Palestinian artists actively engage with concrete, repurposing it as a tool for artistic, civic, and political resistance. They challenge dominant narratives, contest prevailing historical accounts, and confront oppressive structures. Their works reimagine shared spaces, contest the erasure of Palestinian history, and amplify marginalized voices. Concrete becomes a material embodiment of the complexities experienced by Palestinian artists residing and working within the State of Israel, its finally symbolizing resistance and catalyzing the reimagining of alternative futures.

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how concrete is employed and represented within contemporary Palestinian artistic practices, shedding light on its role in shaping Palestinian experiences and contributing to a nuanced understanding of the Palestinian/Israeli context. By exploring the politics of concrete, the article enhances our understanding of its significance in contemporary Palestinian art and its place in the broader discourse of art history.

Palestinian art operating within the confines of the State of Israel constitutes a distinct branch of Palestinian art as a whole. Within this branch, one can discern the presence of what Eyal Weizman refers to as “politics in matter.”1 This mode of artistic expression actively engages in the ongoing struggle for Palestinian identity, nationalism, and human rights. It delves into the realm of action, fully cognizant of the political dynamics that permeate both artistic practice and everyday life. In doing so, it contributes to the exploration and understanding of concrete as a pertinent material in contemporary art creation, the latter located within a broader political fabric that encompasses a wide spectrum of actors utilizing or exerting influence over the implementation, visibility, and impact of the politics surrounding concrete. Consequently, concrete exemplifies the fusion of politics and materiality, effectively demonstrating how political forces infiltrate the built environment, extensive infrastructure systems, environmental conditions, and even the most intimate aspects of individual living conditions.

The present discussion encompasses a range of artistic expressions within the realm of Palestinian art, spanning various media and artistic practices. These artworks seek to portray and enact concrete environments, as well as the ramifications of concrete within both the public and the private spheres. In this context, concrete does not solely serve as a structural backdrop to the Palestinian/Israeli national conflict; rather, it emerges as an active and influential factor in shaping a fundamental political space. This space facilitates and perpetuates a continuous process of dominance and oppression, exemplified through various artistic practices engaged with concrete. Palestinian art unveils concrete as an instrument of oppression within conflict, the material being intricately linked to the destruction and confiscation of Palestinian residential and other areas.

Palestinian art ventures beyond mere reflection and critique of the injustices perpetrated through concrete. Rather, this art appropriates the ostensibly “Israeli-Zionist” concrete, transforming it into a tool for artistic, civic, and political resistance.2 This appropriation can be elucidated through a lens provided by Roberto Fernández Retamar in his exploration of how acts of appropriation are carried out by the colonized as a means to resist and undermine the dominion of the colonizer, thus enabling the colonized to assert their cultural identity and agency from within the very context of colonialism.3 The appropriation of concrete materials thus represents a form of cultural appropriation that facilitates empowerment of the colonized, affording Palestinians the opportunity to reinterpret the culture and language of the colonizer and thereby fundamentally contest the colonizer’s authority all the while reaffirming their own cultural identity. Appropriation, in this context, emerges as a manifestation of resistance and subversion, allowing the colonized to disrupt the narrative constructed by the colonizer by imbuing borrowed elements with their own significance, and thereby challenging the intended message propagated by the colonizer.4

Within the geopolitical context of Israel/Palestine, concrete has assumed multifaceted associations with struggle, violence, destruction, war, and defense. Notably, Germany’s construction of the Atlantic Wall during the Second World War stands as a prominent example of concrete’s utilization as a defensive measure in the military context. According to Paul Virilio, the significance of this fortification line resides primarily in its symbolic value, which Virilio characterizes as a “theatrical gesture.”5, trans. George Collins (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994), 46–47.] Adrian Forty subsequently referred to the Atlantic Wall as a form of “protective clothing.”6 Just as concrete previously had been linked to notions of progress and modernity, its military applications during the Second World War and its subsequent utilization within the geopolitical dynamics of Israel/Palestine, have forged a connection of concrete with enmity and fear. The very concrete that was employed as a means of security and protection in early modernism has been transformed into a symbol of apprehension and aggression towards the enemy.

The subsequent Berlin Wall and the Israeli West Bank barrier are both composed primarily of concrete walls that serve as instruments of division. These structures bear significant national, ethnic, and individual implications. The Berlin Wall on the one hand was perceived in East Germany as a protective barrier against fascism and Western capitalism; on the other hand, that same wall was perceived by the West as a tool for suppressing freedom and liberalism. Similarly the Israeli West Bank barrier is viewed by some Israelis as a security measure vital to the safeguarding of the existence of the State of Israel against armed threats, and as a prerequisite for any form of coexistence, national separation, or prospective political integration. Conversely from the Palestinian viewpoint, the wall-as-barrier manifests issues such as unemployment, poverty, fractured social networks, and a sense of imprisonment akin to living in a ghetto.7

Such interpretive dualities concerning concrete are inherent in the discourse that frames the material. Adrian Forty characterizes concrete as a substance replete with contradictions, defying a singular or unequivocal definition. To Forty, concrete embodies aspects of modernization and associations with industrialization, while also encompassing natural components. And while concrete has been utilized extensively throughout modernity, particularly in the present era—in which its consumption is vast—its usage has a long history, one dating back to ancient Roman times. Although produced using contemporary technological tools, concrete’s application can impose physically demanding labor upon its users. It possesses qualities of both fluidity and solidity, or “crudity and finesse,” as Le Corbusier aptly described it in reference to his Unité d’habitation (1952), thus invoking the juxtaposition of primitive and modern foundations inherent in concrete.8

Extending the potential of concrete even further today, contemporary Palestinian artists like Michael Halak, Saher Miari, Manal Mahamid, and Hannan Abu-Hussein incorporate concrete or its representation into their spatial and architectural works as a critical strategy. Through these artistic interventions, these artists effectively engage with the built environment—walls, checkpoints, borders— employing such concrete structures as powerful sites for resistance and negotiation. Their art confronts oppressive structures, disrupts spatial segregation, and imaginatively envisions alternative possibilities for shared spaces. These artists also address the architectural violence found in structures like separation walls resonating with the concept of “urbicide,” as articulated by Stephen Graham.9 Urbicide encompasses the deliberate undermining or destruction of the Palestinian urban fabric, which has become transformed, for example, into national parks such as the Mount Scopus Slopes National Park built on privately owned Palestinian land; or which is utilized as training areas by the Israeli military, such as in the southern Hebron Hills, resulting in the destruction of homes, erosion of the urban infrastructure, and the imposition of constraints that severely impact the vitality and functionality of urban spaces.10

Concrete Walls of Injustice: Or, dressing the “Naked” wilderness in a “Gown of Concrete and Cement”

Palestinian artist Halak adopts the Hebrew language to serve as the linguistic metonym of the colonialist, in titling his 2014 painting Albishekh salmat beton vamelet (I will clothe you in a gown of concrete and cement). This practice is addressed by the Cuban poet and essayist Roberto Fernández Retamar, who references George Lamming’s explanation that the language imparted by Prospero—the colonial character in William Shakespeare’s, The Tempest—to Caliban, functions as a source of both empowerment and constraint. According to Lamming, “Prospero lives in the absolute certainty that Language, which is his gift to Caliban, is the very prison in which Caliban’s achievements will be realized and restricted.”11 In Halak’s painting, the metaphor of linguistic imprisonment as expounded by Retamar metamorphoses into a harrowing material manifestation resembling a prison camp. In his work, Halak deftly employs both the language of Zionist poetics and the language of representation. Through this nuanced fusion, he crafts a tangible representation that situates him within Caliban’s perspective. Ultimately, this artistic endeavor embodies what can be termed “alien elaboration,” to follow Retamar’s conceptual framework, which is an audacious appropriation of the language, actions, and materials of the colonialist as an integral component of the decolonization process.

Halak’s painting I will clothe you effectively delves into the central theme of concrete, particularly concrete-as-separation-barrier and its visual representation. The artwork is structured along horizontal axes and comprises eight vertical components resembling gray concrete slabs that display signs of incipient fissures. Halak’s choice of industrial acrylic paint intended for wall application, rather than artist-grade acrylic paint intended for canvas, stems from his intention to achieve an optimal material illusion. In a recent interview, the artist has likened the process of crafting his concrete paintings to that of a construction worker laboriously blending materials while fashioning an object.12 Here, the materiality of the painting and the methodology of its production connect not only with avant-garde traditions employing industrial materials but also with tangible material reality. Through the selection of a gray hue, Halak adeptly crafts a graduated spectrum of shades to create a three-dimensional illusion, establishing an effect in which the observers perceive themselves as gazing upon the concrete wall itself, rather than at its pictorial representation.

During its inclusion in Halak’s solo exhibition Fractures, at Noga Gallery, in Tel Aviv, this artwork obscured nearly the entire separation gallery wall, occupying roughly sixty percent of the wall’s height. The artist recalls that the piece elicited diverse reactions, ranging from a sense of suffocation to one of shelter and protection. Halak explains that the essence of his work revolves around raising awareness among the Israeli public concerning the repercussions of the concrete barrier. A review in Haaretz newspaper at the time commented on the installation of the painting, in which the writer asserted that any attempt to discern “what is behind it”—the painting—is ultimately futile; the represented wall functions solely as an obstruction, a tabula rasa devoid of history or future.13 This interpretation perceives the painting as encapsulating the notion that the wall signifies an effort to disrupt the territorial, ethnic, and national continuity among the various regions of Israel/Palestine. Furthermore, the painting symbolizes the endeavor to foster historical and geographical obliviousness through the implementation of the wall as a form of military architecture.

In the early twentieth century, cement—the binding agent in concrete— became intertwined with the Zionist ideology of “Hebrew labor” and the “occupation of labor.”14 This ideology sought to establish the Hebrew laborer as a new Jewish identity distinct from that of the spiritual diasporic Jew, as well as the Arab/Palestinian. The concrete block, according to the early Zionists, rendered Arab expertise in chiseling and plastering obsolete.15

As previously stated, Halak gave his concrete wall painting the apt title I will clothe you in a gown of concrete and cement, drawn from a line in Morning Song by Natan Alterman, a prominent Israeli-Zionist poet.16 In this poem, Alterman employs the first-person plural perspective, signifying the collective “we” of the Zionist Israeli identity. Morning Song was composed as a tribute to the Zionist propaganda film For New Life (1935), in which the poem emphasizes the land as a necessary homeland for redemption, construction, cultivation, and prosperity. It portrays the land as a naked and barren expanse, encircled by hostile adversaries. Edward Said offered his insights into this issue, stating: “All the constitutive energies of Zionism were premised on the excluded presence, that is, the functional absence of ‘native people’ in Palestine; institutions were built deliberately shutting out the natives . . . (to make N.G.) sure the natives would remain in their ‘nonplace.’”17 Retamar similarly articulated, “The Utopian vision can and must do without men of flesh and blood. After all, there is no such place.”18 Indeed, the Zionist aspiration of envisioning the Land of Israel as a utopian realm, akin to a paradise or a land flowing with milk and honey positioned at the periphery of civilization, collides with stark reality. As Retamar astutely observes, this dream becomes vexed by the impudent fact that the place undeniably exists and, as one might naturally expect, it possesses all the virtues and flaws not of an envisioned project but of an authentic reality.19

Concrete serves as a medium for filling voids, dressing the naked land, as portrayed in the poem. In reality it is utilized for constructing a wall, a separation fence that allegedly promises a flourishing life within its fortified confines. Halak’s depiction of this wall, as it has manifested in the Palestinian/Israeli reality, presents an opaque and cracked structure, symbolizing both the brutality and the inherent vulnerability of concrete. These dualities are also mirrored in Alterman’s poem, in which concrete is portrayed as a formidable material embodying resilience, solidity, and fullness, yet bearing cracks and fragility—ultimately revealing its shell-like nature. The full title I will clothe you in a gown of concrete and cement unveils the apparent nakedness of the one who needs to be dressed. Hanan Hever explicates that the poem, embodying an eternal love for the homeland, exposes the fragility and transience of existence.20 The very nature that concrete is meant to cover perpetually indicates the nakedness beneath it. While concrete is expected to ensure eternity, it also reveals the evanescence of national existence.

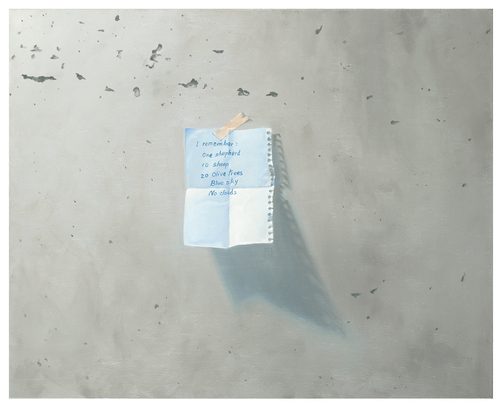

The Palestinian landscapes, whether fortified with concrete or left exposed, serve as poignant reminders of the notion that even seemingly refined, transparent, and natural elements can be the products of discursive engineering. Mitchell argues that landscapes are also about forgetting and escaping from reality, often leading to disorienting dislocations.21 Thus, it becomes crucial to acknowledge that what might appear to be clear, transparent, and familiar, may actually be a deliberate attempt to forget. In another artwork by Halak, Local Landscape (2011), the painting embodies the imperative of remembering, not only in terms of territorial spaces but also in the realm of identity. This painting establishes a strong connection between Palestinians residing within and beyond the wall, traversing the Green Line. While the catalyst for this artwork was Halak’s encounter with farmers affected by the fence’s construction—it impacted agricultural activities such as the caring for olive trees and wheat, and the herding of goats—Local Landscape symbolically addresses Palestinians on both sides of the wall.

A note attached to the wall in the painting bears the following sentence in English: “I remember, one chipper, 10 chips, 20 olive trees, blue sky, no clouds.” This note stands as a testament to those forcibly evicted or deported, and to those whose movements are constrained. It hangs suspended, like a remnant of ghostly beings carried by the wind—entities from the past and present that the concrete-enforced occupation strives to render invisible. Simultaneously, the artwork alludes to something pivotal in the history of Palestinian society in Israel, namely the October 2000 events.22 The numerical figures embedded in the small, cartoon-like print converge on the date 1.10.2000, the day on which the Israeli police killed thirteen Palestinians residing in Israel. This tragic, violent incident has assumed great significance within Arab society in Israel, as it symbolizes the systemic policies and oppression faced by Palestinians, regardless of their geographical location.

ocal Landscape thus establishes a connection between the concrete wall as a manifestation of violent practice and the events of October 2000, which exposed the approach to Palestinians in Israel as that of an enemy to be forcefully restrained by the police. Prior to October 2000, there had been an illusion of the Green Line serving as a dividing line between those Palestinians residing outside and within Israel, the latter supposedly receiving a special status, including equal rights. However, the October events shattered this illusion, revealing it to be a falsehood, as expressed by Raef Zreik: “The Green Line, though still existing in a symbolic sense, underwent a significant shift in meaning, with Israel effectively withdrawing political citizenship that was already limited. This shift was accompanied by political delegitimization and incitement against the leadership of the Arab public in Israel.”23

The theme of silencing and suppression recurs in Halak’s Untitled, a self-portrait in which a concrete brick obstructs the artist’s mouth and is affixed to his face with loose masking tape—and seemingly on the verge of disappearing. The Palestinian figure clings to the board, positioned with his “back to the wall,” while his mouth is symbolically blocked by a brick barrier. In a review of Halek’s solo exhibition “Faces and Landscapes” (2012), at the Tel Aviv Museum (the exhibition opportunity was awarded Halak as part of the Rappaport Prize for an outstanding young artist), the critic highlighted the virtuosity of Halak’s paintings, which depict violence and horror.24 These elements are intricately connected to a pictorial formalism that explores, according to the critic, “patterns of representation and their decomposition.” Halek has provided an additional perspective for comprehending his work: “The term ‘block’ is associated with the utilization of concrete in this piece, as if it serves as a metaphorical translation of concrete, symbolizing a barrier.”25

The concrete wall is part of what Eyal Weizmann has called “the vertical politics of separation and logic of partition” that came to produce appropriation, dissolution, and separation through “structured chaos.”26 Artist Saher Miari has created a form of minor or symbolic disruption of this sort through his gallery installation The Missing Image (2014), which referenced the separation wall.27 The exhibition space featured a simulation of the concrete separation wall, albeit devoid of its physical strength and colonial power. It stood as an empty sign, a potential future monument, resembling a genuine concrete wall but constructed from painted plywood molds. The Bezalel Academy of Art, located near The Hebrew University on Mount Scopus, shares a resemblance with the concrete fortresses as perceived by the neighboring Palestinian villages and neighborhoods. Miari effectively relocated the separation wall and positioned it within the heart of the Israeli art establishment, causing partial disruption to everyday academic life with a barrier impeding access to the study and work spaces of students and faculty members.

The curator of Miari’s solo exhibition referred to the limitations that the artist imposed on the place, writing that they “are an integral part of the language of the place and part of the strategy that Bezalel [Academy] participates in, sometimes without paying attention to it.”28 The wall, constructed by Miari and featured in The Missing Image offered a poignant testament to the deliberate disregard of the real wall’s existence and the pervasive invisibility of Palestinians, both within and beyond the confines of Bezalel and—by extension— Israel. This installation triggered a tumultuous reaction from some observers within Bezalel, a reaction that ultimately played out directly on Miari’s wall. Jewish students covered the wall with graffiti referring, by name, to Jewish victims who had endured attacks perpetrated by Palestinians. Concomitantly, Palestinian students attached to the same wall photocopies of identity cards belonging to Palestinians who had lost their lives in the conflict. While some viewers commended the work, others criticized it for what they perceived as its ethical shortcomings, or as an excessively literal presentation.29

While Miari’s installation alluded to the external activism necessary to challenge the separation wall, Halak’s artwork I will clothe you suggests that the destruction of the wall lies within its own existence. Halak’s pictorial practice offers viewers a photorealistic close-up of the wall, presenting concrete as a pervasive material that threatens to engulf the entire area. Within the concrete itself, however, inevitable cracks and fissures possess the potential to undermine vertical politics and challenge its territorial-political mechanisms. As Mitchell has suggested in a different context, “There is something within walls themselves that wants to breach them and bring them down.”30 The expansive and forceful nature of concrete also carries the risk of its own collapse, opening up possibilities to envision a new horizon.

The Palestinian artworks discussed thus far underscore the act of concealing the lives of Palestinians behind the wall, a perception that echoes a notion articulated by former Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir in a now legendary 1969 interview with The Sunday Times (London), in which she claimed “There was no such thing as Palestinians.”31 This blindness reflects the beginning of Retamar’s aforementioned article, in which he recounts being faced with the question, “Does Latin-American culture exist?” This “question” epitomizes one of the explicit tactics employed by colonialists to challenge the existence of the colonized. To apply Retamar’s framework, the Palestinian becomes a mere “echo of what occurs elsewhere.”32 Israeli skepticism toward the Palestinian identity is palpable in the concrete practices of colonialism discussed here. Indeed, it serves as a foundational impetus underlying Palestinian concrete artistic critical endeavors. A significant portion of Miari’s work, for example, seeks to materialize the memories, absences, and traumas inherent in the repressed Palestinian history.

Palestinian De-construction of The Raft of Concrete

Concrete, often associated with “erasing and obliterating memory, cutting people off from their past, from themselves,” has taken on a different significance in the works of Palestinian artists.33 It has become a material for preserving memory, not because concrete has acquired commemorative properties in modernity or is inherently capable of elevating memories. Rather, its significance lies in the Palestinians’ lived experiences, which are deeply intertwined with the ongoing Nakba (“disaster” or “catastrophe”) and the systematic attempts to erase Palestinian memory and material traces of life and culture. Concrete is frequently employed in acts of violence against Palestinian structures, targeting their stability and perceived permanence. Houses, facilities, and places constructed with concrete are destroyed or buried using this same material, while settler construction projects utilize concrete to assert control over Palestinian geopolitical space. In Palestinian art, concrete is appropriated as a means of cultural reflection, serving to materialize memory and challenge attempts at erasure.

Miari’s painting Boat in a Sea of Concrete (2018), presented in a circular format in mixed media on plywood, portrays a landscape as if observed and reflected through a telescope. The composition is divided by a black horizontal line, below which a sinking boat emerges from a sea of concrete that encompasses the entire space. This concrete painting is part of a series of works by the artist in which a boat serves as a recurring image or object juxtaposed with a concrete environment. In 2008, Miari exhibited a truncated wooden boat, its lower portion cast in concrete and iron, as part of the exhibition Blocked Space at The Kabri Gallery in the Galilee. Positioned as a barrier between the entrance doors and the gallery corridor, the non-functional boat obstructed the passage, serving as a symbol of restriction or control. The boat reappeared in Miari’s subsequent exhibitions, such as in a solo exhibition at the Umm El Fahm Art Gallery, in the sculpture Displacement (2019), where the boat emerged from the wall, still resembling a fishing vessel but with a concrete bottom. Miari’s boat in this instance symbolizes a longing for Palestinian identity, homeland, and freedom, metaphorically representing themes of exile, displacement, fragility of life, and a sense of belonging and loss. The concrete material infused into Miari’s boats establishes a connection to monuments, embodying the memory of Palestinian residents engaged in fishing who were forcibly relocated—including Miari’s own family—from Acre to the village of Jadeidi-Makr. Miari employs concrete within the context of displacement and uprooting caused by colonialism, as evident in his installation Raft (2020). Consisting of two cast concrete slabs lying on wooden surfaces, it connects two acts of displacement: the Jewish displacement, symbolized by the presence of the Israeli brutalist concrete wall on one side of the artwork, and the Palestinian displacement, symbolically represented by the concrete floor. Raft alludes to the plight of Palestinian and Jewish refugees and, reminiscent of Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19), introduces themes of “social injustices, including refugee abandonment, racism, inequality, and cruelty” into the realm of representation in Israel.”34 Miari’s utilization of concrete in the boat artworks establishes a connection between these works with statues and monuments constructed for commemoration, as the artist employs concrete as a medium that “materializes memory.”35

Saher Miari, born in 1974 in the village of Makr, is a Palestinian artist-builder residing and practicing in Israel. His background and expertise as a builder significantly influences his sculpture, painting, and installation works, in which concrete—along with iron and wood—assumes a central role in conveying meaning. Concrete is employed in Miari’s artistic practice within national, political, and artistic contexts, as a material that encapsulates the complex interplay between Palestinian and Israeli identities. Concrete manifests in Miari’s creation of architectural objects and representations of construction processes—and it even finds its way into more traditional artistic genres such as painting. As a utilitarian and ubiquitous material in both everyday and artistic realms, concrete in Miari’s work particularly embodies a continual negotiation by the artist between racist, colonialist, Western, and Israeli concepts. Hence, one can discern a tension within Miari’s artistic practice that intersects with notions of “Arab work” or “black work,” terms coined in Israel as derogatory references to Arab/Palestinian labor, as juxtaposed with “Hebrew work” and “land occupation” as legitimate modern Hebrew practices. Thus, concrete acts as a conduit for grappling with the tension between a Hebrew-Jewish ethos of construction and a perceived Palestinian ethos of destruction—and ultimately between a Hebrew/Jewish pioneer (Halutz) and an Arab worker.36

Miari regards concrete as a foreign material introduced into Palestine by architects originating from outside the region. Such architects sought to supplant the local styles and building methods of the Orient with what they regarded as a new, European, and modern construction approach. Concrete emerged as a replacement for stone and became intrinsically tied to the forging of a new Israeli identity.37 Indeed, concrete played a significant role within the national-Zionist ethos, both in the realms of military and security architecture, and in private and civic construction. Even the “visionary of the state,” Theodor Herzl (1860–1904), envisioned a cement factory as part of the Zionist revival of the Jewish people.38), 217–18.] Throughout the modern settlement activities of Jews in Palestine, concrete has become symbolic of the Zionist ethos, offering a modern Hebrew alternative to ancient Arab stone construction.

In the early years of the State of Israel local architects embraced concrete as an “Israeli material” that could contribute to the creation of a distinct national identity.”39 Architect Ram Karmi, in a 1998 interview, portrayed concrete as a fitting medium for Zionist/Israeli/national construction, stating, “Within the general current of international architecture, a new, Israeli generation has grown here . . . for us, concrete was the Israeli material. Concrete gave the feeling of stability: once it was placed, it would not be moved.”40 Karmi also emphasized the contrast between concrete-based Hebrew modernity and Arabism, asserting that “Just as the stone, the basic unit for designing arches, domes, openings and windows, unites the versatility of the Arab village—this is how the concrete, which I use here [at the Lady Davis Neot Afeka “Amal” School] a lot, unifies the formal versatility of the school.”41 Thus in the Israeli architectural and cultural context, concrete has become synonymous with growth, expansion, stability, rootedness, and security.

Nevertheless, in Miari’s interpretation, concrete assumes a different connotation.42 He perceives concrete as an alien material—a harbinger of oppression that threatens to submerge life. From his perspective, concrete represents the tool through which colonial forces displace and eliminate the indigenous Palestinian population from their land. It is seen as both a purifier and a defiler of space, disrupting the fabric of life. This perspective forms the backdrop for Miari’s deliberate appropriation of concrete as a conduit for reflecting on the Palestinian geopolitical reality. By adopting the very material employed by the colonialists, he transforms it into a medium for remembrance, resonance, and commemoration of both past and ongoing Nakba experiences.

According to Retamar, the colonized individual who employs the tools and concepts of the occupier is engaging in an act of resistance against colonial domination. The deportation, displacement, and destruction of the Palestinian social fabric find representation in the elegiac artworks of Miari, who, in the context described by Retamar, can be likened to one who has been “robbed of his island” and whose ancestors suffered violence. He appears to act not only because he has no other choice, but possibly also—at least at times—as a deliberate critical choice, employing the language and tools of the colonialist as a means of resistance. In the Palestinian context, concrete assumes a role akin to language in Retamar’s Latin America, serving as a medium through which the occupied express their desire to challenge the prevailing assumptions that shape the region’s history and politics. In the words of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, “The culture of Caliban is the culture of resistance that turns the weapons of colonial domination back against it.”43 This perspective offers an effective framework for interpreting artworks that reveal the labor of the colonized within the Israeli security architecture, offering a subversive or non-functional simulation of that architecture.

The Construction of Concrete Shelters by Unshielded Palestinian Lives

Palestinian society in Israel has undergone significant transformations and challenges since 1948, as documented by sociologist Salim Tamari. One notable aspect of this is the shift in employment patterns, with a decline in agricultural jobs and a growing presence in industries marked by instability, such as the construction sector.44 Concrete has emerged as a central material in the labor of Palestinian workers. According to Miari, these workers have become “builders of the Land of Israel, or the national home,” even though they have been dispossessed of their own homes, thereby participating involuntarily in the erasure of their people’s history.45

Miari characterizes the work of these builders and laborers in concrete construction as a “mandatory service” for young Arabs in the country before continuing on to academic studies.46 In his video installation With One of His Hands Wrought in the Work . . . (2017), Miari presented faceless figures of Arab workers engaged in construction activities, their identities reduced to mere mechanical actions during the process of building a shelter. The video work suggests that these workers are rendered transparent, forced to toil in inhumane conditions that erase their individuality within the Zionist construction narrative. The title of the artwork is derived from the biblical verse, “They all built the wall and they that bare burdens laden themselves; each one with one of his hands wrought in the work, and with the other held a weapon” (Nehemiah 4:17). The verse indicates that along with their labor, these workers also need to defend themselves. By omitting the second part of the verse from the artwork’s title, Miari emphasized the workers’ exposure to danger. The absence of the weapon (Shelah/sword in the original quote), the tool of defense, in the portrayal of the workers, underscores their vulnerability to exploitation and erasure as they construct a means of defense for those who view them as enemies—all the while remaining unprotected themselves.

In the exhibition Ahmad al-Arabi, Miari presented the installation Intermediate State 2 (2019), featuring a cast concrete wall adorned with the iron ventilation pipes typically found in Israeli air-raid shelters.47 The wall was positioned as a column in the center of the space without conjoining the room’s ceiling or side walls, Miari’s wall thus being denied its functional purpose, just as the ventilation pipes prove equally non-functional in no longer facilitating air circulation. This fragment of a shelter thus no longer provides protection; the wall is a remnant of a security structure that has been rendered ineffective. Miari explores various iterations of this work in open-air spaces as well, where he uses the ventilation ducts to play recordings of conversations among Palestinian construction workers, offering an ironic perspective on the illusion of complete protection against the perceived Arab enemy, who ironically contributes to the construction of security spaces using concrete.

Intermediate State 2 connects back to Miari’s installation and solo exhibition Gray Space (The Kabri Gallery, curated by Drora Dekel, 2012), in which he transformed the gallery space into a shelter by casting concrete slabs and embedded non-functional ventilation pipes in them. In one wall of the “shelter,” a simulated window opened, suggesting an exit from the sealed concrete space. Within this window, a video work shown on a television featured conversations in Arabic among Palestinian construction workers. Once again, it became evident to viewers that Palestinian workers, not Hebrew pioneers, have built the concrete structures that dominate the Israeli landscape.

The notion of shelter and its construction holds significant importance in the Israeli security concept, with concrete serving as a central material that underpins the country’s security infrastructure. Concrete becomes a crucial element in establishing protected spaces, reinforcing the perception of Israel as a constantly threatened territory. Miari aptly remarks,“‘The Land of Refuge’ is not an historical symbol that has passed its time,” underscoring the ongoing fascination, not to say fixation, of shelter and security in Israeli society.48 A shelter, much like a wall, represents a place of refuge in times of threat. It functions as a dividing line, polarizing and preventing dialogue between parties. Beyond its boundaries, everything is perceived as an existential danger, further emphasizing the division between victim and aggressor. Those who seek shelter are not required to confront the violent aspects or characteristics inherent within themselves. This phenomenon reflects a “paranoid position” prevalent in Israeli society, where concrete and security are sanctified through the symbol of the shelter.49

In his work, Gray Space (2012), in which Miari turned Kabri Gallery into a shelter, and as in his various installations that scatter fragments of a shelter in the Israeli public space, the artist alludes to what can be called the abundance or over-building of shelters in Israeli society. Since the 1980s—and particularly in the 1990s—the Israeli government has gradually privatized the defense of citizens during times of war. The architects Tula Amir and Shelly Cohen have examined the shift from collective protection spaces, such as public concrete shelters, to the individually owned shelter known as a “residential protected space.” These private shelters are financed and constructed by the private market, placing the financial burden of the construction and maintenance of these “safe rooms” on individual citizens. Instead of in collective spaces that foster cooperation and support, anxiety is now internalized within the private homes of individuals—existential anxiety itself having undergone a process of privatization.50

Residential protected spaces in Israel are constructed inside homes according to specific requirements and guidelines, such as those pertaining to the recommended thickness of concrete, with the aim of preparing citizens for war and cultivating national resilience. Miari’s artistic exploration of the theme, his enveloping artistic spaces in shelter aesthetics and the language of residential protection, exemplifies the sense of excess associated with the security ethos. This excess protection signifies a process of fortification that rejects the prospect of a political solution. The depiction of sheltering in Gray Space conveys the omnipresence of security threats in the lives of Israeli residents, as heightened sheltering and protection normalize a state of war, absolving Israeli society of any responsibility to change the situation. Ultimately, this intensified self-protection ethos reinforces the “sense of victimhood . . . [and] fosters a preference for offensive action while rejecting peace initiatives.”51

The portrayal of Palestinian concrete workers in Miari’s works, particularly in Intermediate State 2 and Gray Space, is meant to amplify their voices and expose their erasure while presenting an ironic critique of the illusion of complete protection against the Arab enemy—the very individuals involved in constructing the concrete security spaces.

Miari transforms the concrete shelter into a meeting place between Palestinian and Israeli adversaries, liberating it from its sterile and ethnically defined confines, and thus creating a hybrid space that allows for dialogue and speech, even if it does not conceal the realities of oppression, binary divisions, and colonialism. In a sense, Miari compels the residents of the Jewish National Home to acknowledge the potential of the concrete house as a “border zone,” a concept suggested by Homi Bhabha.52 This implies recognizing the political and cultural mechanisms that shape borders and influence our perception of reality, indeed fostering a critical awareness of borders and enabling multivocal discussions of them. Such recognition opens up the possibility for movement and progress beyond the confines of existing borders.

Miari’s critique extends beyond a general, or blanket condemnation of the concept of ethnic purity inherent in the occupation. His specific examination of concrete and its role in construction, particularly in the establishment of residential or collective sheltered spaces within Israeli society, suggests that these spaces serve as generators of anxiety, ultimately legitimizing colonialism. According to Miari, the personal residential shelter, or safe room, can be seen as a “fragment detached from the whole house…constructed with reinforced concrete . . . a space that is detached from its surroundings, symbolizing threat and anxiety.”53

This perspective also sheds light on Miari’s artistic reproduction of concrete construction, specifically the construction of “defensive” security structures. In his works, Miari neutralizes the defensive and protective function of reinforced concrete by stripping it away. Instead, his concrete spaces utilize this material as a medium to create simulated environments that ultimately convey a sense of vulnerability and fragility.

De-concretizing the Palestinian Home

The Palestinian artwork that presents a distorted war architecture such as a wall or shelter can be likened—to a form of Calibanesque babbling, a purposely erroneous or imperfect imitation of a practice otherwise perceived by the Israeli army as an assertion of the occupier’s self-empowerment. This practice is transformed through Palestinian creative adaptation and reterritorialization of concrete architecture into an act rendered futile. Such a decolonizing practice focusing on the Palestinian home may be recognized in the works of Palestinian artists Manal Mahamid and Abu Hussein, both of whom might be said to introduce to such a decolonizing practice a form of colonial mimicry.

Mahamid and Hussein’s underlying, shared intention—while working entirely independent of each other—is to challenge the conventional use of concrete as a material or object, by transforming the medium into something defective, partial, and subversive. In an untitled installation created expressly for the group exhibition More than That, at the Sommer Gallery in Tel Aviv, in 2003, Mahamid constructed a wall from black building buckets; the structure was then filled by the artist with thousands of red roses that were left to rot over the course of the exhibition. Mahamid had purposefully created a contrast between the decorative placement of the wall, which occupied the designated display space for her artwork, and the space adjacent to it. By forcefully breaking through the wall that confined her exhibition space, the artist disrupted the aesthetic arrangement. She aggressively and unexpectedly punched two holes in the concrete wall, leaving the remnants of the destruction in the newly opened area.54 This act by Mahamid mirrors the practice employed by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) during their April 2002 attack on the city of Nablus, known as “inverse geometry.”55 This offensive military strategy involves restructuring the architectural dynamics of a site through actions that undermine the logic of architecture, reversing the relationship between interior and exterior, thus transforming the normative boundary separating the private and the public domains. The strategy shatters spatial definitions through transgressive acts aimed at sowing chaos.

Mahamid appropriated this strategy of destruction, the so-called “inverse geometry,” as a form of artistic expression, her artwork thus assuming a kind of “design by destruction,” albeit she had of course obtained permission for the subversive act from the gallery owners.[Ibid., 201.] By doing so, she placed the strategies of dismantling, appropriating, and disrupting living spaces at the heart of the Israeli bourgeois space in Tel Aviv. In this context, Mahamid symbolized a struggle for control, employing a strategy that challenged hierarchical structures, reflecting an ongoing struggle for autonomy and existence. She placed the Palestinian home and the military strategies employed to destroy it at the forefront of the public discourse. Cameron Parsell illuminates the significance of this action in commenting that “control over a space is important to people’s understanding of what it means to be at home, because this control over a space also means the ability to exercise a degree of autonomy over their lives.”56

In Mahamid’s subsequent installation Raped Space (2004), at Umm el-Fahem Art Gallery, concrete-filled barrels effectively obstructed the designated display space assigned to her. The installation referenced the practice of sealing houses and spatial blocking, which has become increasingly prevalent in colonial practices. Whether through the establishment of new settlements, the imposition of checkpoints, the designating of permitted and prohibited roads, or the imposition of ever-changing restrictions and prohibitions applying to Palestinian spaces, concrete emerges as the material of segregation between Israelis and Palestinians. Through Raped Space Mahamid embodied what Ellen Pavey (following Eyal Weizman) describes as the “pervasive and chaotic ‘conditions of segregation.’”57

Mahamid’s Raped Space moreover directly addressed the Israeli army’s process of sealing Palestinian homes.58 That same theme is echoed in other artists’ works, such as Hannan Abu Hussein’s more recent installation Build Your Home and Destroy It with Your Own Hands (2021)).59 In Build Your Home, Hussein constructed a concrete house only to demolish by hand, the composite act symbolizing her experiences of visiting the Issawiya neighborhood in East Jerusalem. There, she witnessed the ruins of houses that had been destroyed by their own inhabitants under order of the Israeli occupation forces.60 Similarly, Mahamid’s manipulated, still photo Israel is Killing Me, of 2008, offered a response to the forced demolition of a section of a family member’s house ostensibly due to the owner’s lack of proper construction permits.61 In both cases, sealed or shattered concrete becomes intimately linked to the essence of Palestinian existence—the Palestinian home.

The Palestinian home indeed holds a central position within Palestinian society and serves as a focal point in Ariel Handel’s “Critical Theory of Housing/Dwelling.” Handel’s theory embodies the understanding of home and domesticity within the confines of limitations (regarding construction and demolition), tradition (as a multigenerational residence), and the inherent function of the house as a space for survival since the 1948 Nakba. The Palestinian home, as both a concept and an object, thus holds both historical and political significance.62 It has become a common target of Israeli regime actions seeking to control and govern Palestinian spaces and populations. These actions include land expropriation and the continuous criminalizing of Palestinians often forced to defy the regulations since, for instance, the obtaining of a construction permit for house additions or other construction is exceptionally rare for a Palestinian living within Israel. The Palestinian house is in constant jeopardy, exposed to punishment and collapse within a state pervaded by policing and warfare.

Bree Akesson provides a nuanced and multidimensional depiction of the Palestinian home, depicting it as a site caught within the grip of occupation and colonialism. The home thus embodies both positive and negative realities and images. Akesson notes that the residents of Palestinian homes are confined within a cage, where living conditions might be unhealthy, cramped, and lacking privacy, resembling a stay in prison. However, she also emphasizes that the Palestinian home represents a protective castle, a space for being, familial practices, and a locus of identification and shelter.63 Thus, in addition to being subjected to policing, restriction, and oppression, the Palestinian home assumes a crucial role as a site of hope, imagination, socialization, and everyday life—a place to carve out subsistence and resistance, as articulated by Handel.64 The home as such symbolizes a secure haven for the formation of family and Palestinian collective identities, encompassing a sense of security, identity, familial ties, multigenerational heritage, and material wellbeing amidst the backdrop of ongoing conflict.65

The artistic representations of house destruction through concrete blocking in Mahamid’s Raped Space and Abu-Hussein’s construction and subsequent destruction of a concrete house by one’s own hands similarly highlight the significance of dismantling, sealing, blocking, and violence as various means to undermine the formation of Palestinian agency. These actions directly challenge the spaces where Palestinian individuals develop their identities and resistance. Christopher Harker further underscores the interconnectedness of Palestinian identity in family, clan, and the Palestinian home, drawing special attention to the Palestinian “practice of living in close proximity to immediate and extended family.”66

Consequently, the destruction, sealing, or expropriation of Palestinian homes signify not only the loss of a secure living space but also the deprivation of a “stable future.”67 This echoes the actions of the Israeli army, which seals or demolishes houses, effectively displacing families or communities from their interconnected (and intraconnected) habitats and severing their ties to the everyday living environment. The concrete used in these art installations serves to represent a form of collective punishment that results in the dispossession of homes. The acts of destruction and obstruction depicted in these artworks embody the usurpation of space and negate the possibility of comprehending the significance of a Palestinian geography and spatiality. In this context, concrete, whether utilized as solid barrier or represented as shattered material, becomes a manifestation of colonialist actions aimed at seizing and dominating space. It symbolizes the encroachment of the colonial power upon the Palestinian landscape.

Recurring motifs of concrete columns and reinforced concrete surfaces can be observed in several of Mahamid’s works. The installation Boxing Ring (2002) featured columns extended with iron rods, the erect assembly forming a boxing ring that symbolized problematic gendered, national, personal, and political realities. The ring was enclosed by four cast concrete columns of varying heights, with the exposed iron rods contributing to the overall sense of reinforcement of the storied material. In Mahamid’s aquatint print A column (2002), and the concrete installation Dance with the Owls (2015), the image of the column and concrete surface with iron rods reappears, to similar effect.

This imagery of the column and reinforced concrete surface bears a distinct reference to Palestinian communities, where it is customary for the builders to leave in place columns with exposed iron rods protruding from the top of the columns after completing the construction of a house. These columns serve as readied pylons for the potential addition of floors in the future, evoking the prospect of continuity across generations of the same family. Each completed building not only represents the present but also signifies the potential for future construction, ensuring the ongoing existence of the Palestinian house. This artistic practice, embodied in the concrete column, reflects the concept of Palestinian “sumūd” (steadfastness). Sumūd encompasses notions of adherence, resilience, and unwavering determination.68 It encompasses memory, imagination, artistic expression, and national agency, as well as the preservation of life and resistance against those who would deny it.

While the Israeli national identity portrays itself as modern, utilizing concrete as a tool of both material utility and symbolic expression—a multidisciplinary means of conveying and educating all local inhabitants—the conquered have strategically adopted the conqueror’s language of expression, expressly to challenge its validity, authority, and morality. As Retamar suggests, “We have only a few languages with which to understand one another: those of the colonizers”, underscoring the linguistic dependency established by the occupier over the occupied.69 This condition does not, however, diminish the centrality of Arab and Palestinian culture and language as the foundation of Palestinian identity.

In Miari’s decolonializing 2017 video installation With One of His Hands Wrought in the Work . . ., as earlier discussed, it is worth recalling that the artist inscribed on a concrete wall a sentence in Arabic letters from the Book of Nehemiah—a sentence originally referencing the Zionist pioneers. Reading the Arabic letters reveals that the sentence is from the Hebrew transcribed into Arabic, reading, “Baahat Yado Osse Bamelacha,” meaning “With One of His Hands Wrought in the Work.” However, in Miari’s installation the pioneers are the Palestinians. Much like language, then, concrete is appropriated in this artwork to serve as a radical critique of colonial violence. Similar to Shakespeare’s Caliban, Palestinian artists appropriate both concrete and language, turning each against the Zionist narrative, and echoing Caliban’s telling exclamation: “You taught me language, and my profit is not. I know how to curse. The red plague rid you/For teaching me your language!”[Ibid.]

Nissim Gal is Senior Lecturer and Head of Graduate Studies at the Department of Art History, University of Haifa. He is the author of The Portrait of the Artist as a Facial Design (2010), and Ilana Salama Ortar: La plage tranquille (2007). He is currently editing the anthology De Tours of Modern Art, scheduled for release later this year. [Department of Art History, University of Haifa, Mt. Carmel, Haifa, 31905, Israel, nissimgal.haifa.university@gmail.com].

- Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation (London: Verso, 2014), 5. Palestinian society encompasses diverse geopolitical spaces, including Gaza and the West Bank, Palestinians in Israel, the Palestinian diaspora in the Arab world, and the Palestinian diaspora in Europe and the United States. This article specifically examines the artistic endeavors of Palestinian artists residing in Israel, who have trained and gained recognition within Israeli art institutions. Despite their engagement with the Israeli art scene, these artists continue to produce concrete art that defies the “alleged” boundaries and dichotomies that separate the Palestinians living “inside” and those residing “outside.” ↩

- It should be noted that this article does not assert that cement or concrete are Zionist/Israeli inventions. Rather, the focus is on Palestinian artists residing within the State of Israel whose work challenges the Zionist ethos that associates concrete with an “Israeli material.” Further elaboration on this topic will be provided later in the article. For more information, refer to footnote 5. ↩

- See Roberto Fernández Retamar, “Caliban: Notes Toward a Discussion of Culture in Our America,” trans. Lynn Garafola, David Arthur McMurray, and Robert Marquez, Massachusetts Review 15 (Winter–Spring 1974): 7–72. All subsequent references by the author to Retamar’s “Caliban” essay are drawn from this source. ↩

- See Said’s reference and confirmation of Retamar’s view of decolonization in Edward W. Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), 213. This appropriation is achieved through what is commonly referred to as the “politics of materials”—in this case the politics of concrete.[5.Cement, along with the concrete it infuses, played diverse roles in the economic, emotional, political, and material realms during the twentieth century, both within the Zionist and the Palestinian national movements. Palestinian endeavors to increase cement imports or to establish local cement factories encountered opposition from the High Commissioner and the British Mandate authorities in Palestine. For a comprehensive examination of the politics of concrete in the Palestinian-Israeli context, refer to Nimrod Ben Zeev, “Building to Survive: The Politics of Cement in Mandate Palestine,” Jerusalem Quarterly 79 (Autumn 2019); 39–62. Cement is profoundly significant in Palestinian refugee camps and houses within and outside the Green Line. It symbolizes resilience, identity, and the determination to maintain heritage, foster stability, and resist displacement; see also Nasser Abourahme, “Assembling and Spilling-Over: Towards an ‘Ethnography of Cement’ in a Palestinian Refugee Camp,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39, no. 2 (March 2015): 200–17, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12155. ↩

- Paul Virilio, Bunker Archaeology [1975 ↩

- Adrian Forty, Concrete and Culture: A Material History (London: Reaktion Books, 2012), 179. ↩

- See Christine Leuenberger, “From the Berlin Wall to the West Bank Barrier: How Material Objects and Psychological Theories Can be Used to Construct Individual and Cultural Traits”, in Katharina Gerstenberger and Jana Evans Braziel, eds., After the Berlin Wall: Germany and Beyond (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 59–83. ↩

- Forty, Concrete and Culture, 38. ↩

- Stephen Graham, “Lessons in Urbicide,” New Left Review 19 (January–February 2003), 63–78; and Graham, “Constructing Urbicide by Bulldozer in the Occupied Territories,” in Stephen Graham, ed., Cities, War and Terrorism: Towards an Urban Geopolitics (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004), 192–213. ↩

- See “National parks as a tool for constraining Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem,” B’Tselem, September 16, 2014. ↩

- George Lamming, The Pleasures of Exile (London: Michael Joseph, 1960), 109; quoted by the author from Retamar, “Caliban,” trans. Lynn Garafola, et al., 22. ↩

- All of Michael Halak’s statements in this article are derived from an interview conducted by Mayar Zwehid (via Zoom) on January 18, 2022. ↩

- Galia Yahav, “Michael Halak’s Lost Horizon Line,” Haaretz, April 4, 2014. ↩

- Or Aleksandrowicz, “Gravel, Cement, Arabs, Jews: How to Build a Hebrew City,” Theory and Criticism 36 (Spring 2010): 65 (in Hebrew). ↩

- Aleksandrowicz, “Gravel, Cement, Arabs, Jews, 82. ↩

- See Natan Alertman, Pizmonim ve-Shire–Zemer: Kerakh Rishon and Kerakh Sheni, Menahem Dorman and Rinah Klinov, eds. (Tel Aviv: Hotsa’at Ha-Kibuts Ha-Me’uhad, 1976), 302–03 (in Hebrew). ↩

- Edward Said, “Zionism from the Standpoint of its Victims,” in The Edward Said Reader, Moustafa Bayoumi and Andrew Rubin, eds. (New York: Vintage Books, 2000), 139. ↩

- Retamar, “Caliban,” trans. Lynn Garafola, et al., 15. ↩

- Retamar, “Caliban,” trans. Lynn Garafola, et al., 13. ↩

- Hannan Hever, “A Cement-trap for Ivory!,” in The Poetry of the Concrete (Tel Aviv: Eretz Israel Museum, 2009), 33–34 (in Hebrew). ↩

- W. J. T. Mitchell, “Holy Landscape: Israel, Palestine and the American Wilderness,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 26, no. 2 (2000): 196. ↩

- The October 2000 events or October eruption constituted a series of events of protest involving Palestinian citizens of Israel. The events occurred shortly after the outbreak of the Second Intifada and specifically involved confrontations between Israeli forces and Palestinian protesters who held Israeli citizenship. During this period, 12 Palestinian citizens of Israel and one non-Israeli Palestinian were killed by Israeli mortar fire; an Israeli Jew was also killed by stone-throwing. ↩

- Raef Zreik, a lecturer in the philosophy of law at the Minerva Center, Tel Aviv University, and the Ono Academic College, as quoted in Jack Khoury, “20 years after the October events, the families of the victims still demand justice,” Haaretz, January 10, 2020. ↩

- Smadar Sheffi, “Michael Halak’s Exhibition: His Grouped Silences,” Haaretz, April 3, 2012. ↩

- Interview with the artist conducted by Mayar Zwehid (via Zoom), January 18, 2022. ↩

- Weizman, Hollow Land, 5–6. ↩

- Saher Miari’s solo exhibition The Missing Image, curated by Dor Guez, was held at the photography gallery of the Bezalel Academy, Jerusalem, in 2014. ↩

- Dor Guez, Saher Miari, Ahmad al-Arabi, exh. cat. (Umm El Fahm: The Umm El Fahm Art Gallery, 2019), 38. ↩

- Sahar Miari in an interview with the author, September 22, 2023. ↩

- W. J. T. Mitchell, “Christo’s Gates and Gilo’s Wall,” Critical Inquiry 32, vol. 4 (Summer 2006): 600. ↩

- Interview of Golda Meier by Frank Giles, “Golda Meier: ‘Who can Blame Israel,’” The Sunday Times, June 15, 1969. ↩

- Retamar, “Caliban,” trans. Lynn Garafola, et al., 7. ↩

- Forty, Concrete Culture, 197. ↩

- Tal Bechler, “Wrought in Their Work”, exh. statement (virtual), Saher Miari: Horizon – September 2020, Kupferman Collection House, Kibbutz Lohamei Haghetaot, 2020. ↩

- The use of concrete for the construction of monuments is a prevalent practice. One illustrative instance is that of the base of the Sachneen monument, which commemorates Land Day and its victims. The rectangular concrete structure resembls a cast sarcophagus, while accompanying figurines are crafted from aluminum. I will revisit this topic within the framework of Mahmid’s work later in this article. ↩

- See the oppositions in Miari’s work in Guez, Sahar Miari, 27. ↩

- Interview of Sahar Miari by Mariam Younes, 2021 (unpublished). ↩

- Theodor Herzl, Old-New Land, trans. Lotta Levensohn (New York: Markus Weiner and Herzl, 1987 [1941 ↩

- Zvi Efrat, The Israeli Project (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2000), 105. ↩

- Ram Karmi in conversation with Zvi Efrat, The Israeli Project, 107. ↩

- Efrat, The Israeli Project, 107. ↩

- According to Miari in an unpublished interview of the artist by Mariam Younes. ↩

- Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Commonwealth (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 98. ↩

- Salim Tamari, “The Palestinian Society: Continuity and Change,” in Adel Manaa, ed., The Palestinians in the Twentieth Century: A View from Within (Jerusalem: Van Leer Jerusalem Institute, 1999), 31–61 (in Hebrew). According to recent estimations, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians are employed in the construction industry in Israel and in the Israeli settlements. When combined with the Palestinians residing in Israel, they constitute over 70 percent of the total workforce. Additionally, authorized migrant workers from targeted countries like China contribute to this labor force. For further information, see Lucy Garbett, “Palestinian Workers in Israel Caught Between Indispensable and Disposable,” Middle East Report Online, May 15, 2020. ↩

- Saher Miari, in Exhibition of Graduates of the Master’s Degree in Art, University of Haifa 2018, exh. cat. (Haifa: University of Haifa, 2018), 32. ↩

- Miari is quoted in Drora Dekel, “Sahar Miari ‘Grey Space,’” a text that accompanied the exhibition Grey Space at Kibbutz Kabri, April 2012. ↩

- Intermediate State 2 (in the exhibition catalog, the title of the work is translated as Medium Position 2), 2018, poured concrete on plywood, ventilation tubes, and sound, 220 x 120 x 25 cm (87 x 47 x 10 in.), exhibited in Dor Guez, Saher Miari, Ahmad al-Arabi, 50–51. ↩

- Miari in Exhibition of Graduates, 32. It should be noted here that “refuge” and “shelter” are the same word in Hebrew: miklat. ↩

- Daphna Bahat and Gabi Bonwitt, “Shelter as Existential Metaphor,” in Shelter Land/Constructed Civil Defense, eds. Shelly Cohen, et al. (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University – Gania Schreiber University Art Gallery, 2010), 96, 99. ↩

- Tula Amir and Shelly Cohen, “From Public Shelter to Residential Shelter: The Privatization of Civil Defense,” in eds. Shelly Cohen, et al., Shelter Land/Constructed Civil Defense, 41–54. ↩

- Shelly Cohen, et al., “Will we shield ourselves to the point of insanity?” in Shelter Land/Constructed Civil Defense, 16. The concepts of “cultural militarism” and “civil militarism” coined by Baruch Kimmerling emerge here, attesting to the dramatic presence of the military in the collective experience and identity; see Baruch Kimmerling, “Militarism in Israeli Society,” Theory and Criticism 4 (1993): 123–40 (in Hebrew). ↩

- Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994), 9–18. ↩

- Miari in Exhibition of Graduates, 32. ↩

- Tali Shamir, “The Poetics of Stench,” Walla Tarbut, August 6, 2003. ↩

- Weizman, Hollow Land, 185. ↩

- Cameron Parsell, “Home is where the house is: The meaning of home for people sleeping rough,” Housing Studies 27, vol. 2 (2012): 160. ↩

- Weizman, Hollow Land, 177; and Ellen Pavey, “Politics in Matter,” Omnipresence, exh. cat. (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2018), 29. ↩

- This is according to an unpublished interview between Manal Mahamid, Mais Abu Hamid, and Nassev Awad, May 27, 2022. ↩

- Presented as part of the group exhibition, In Concrete Stones, curated by Maayan Sheleff, Art Cube Artis’s Studios, Jerusalem, July–August 2021. ↩

- According to an annual report published by the Palestinian Land Research Center, approximately 950 houses and structures owned by Palestinians were demolished by Israeli authorities in the West Bank area, along within the East Jerusalem region, during 2022. The report noted that 65 of the homes were demolished by their owners under the orders of the Israeli occupation forces. According to their statement, a total of 2,290 residential and commercial structures received an order of demolition; see “A Brief of Israeli Violations Against Palestinian Land and Housing Rights for 2022,” December 28, 2022. ↩

- Manal Mahamid, Israel Killing Me, 2008, manipulated still image, 20 x 27½ in. (50 x 70). ↩

- Ariel Handel, “What’s in a Home? Toward a Critical Theory of Housing/Dwelling,” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 37, no. 6 (2019): 1045–62. ↩

- Bree Akesson, “Castle and Cage: Meanings of Home for Palestinian Children and Families,” Global Social Welfare 1 (2014): 81–95. ↩

- Handel, “What’s in a Home?,” 9. ↩

- Christopher Harker, “Spacing Palestine through the Home,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 34, no. 3 (2009): 320–32. ↩

- Ibid., 325. ↩

- Ibid., 326. ↩

- Nurhan Abujidi, Urbicide in Palestine: Spaces of Oppression and Resilience (London and New York: Routledge, 2014); Rema Hammami, “On the Importance of Thugs: The Moral Economy of a Checkpoint,” Middle East Report 231 (Summer 2004): 26–34; Raja Shehadeh, The Third Way, A Journal of Life in the West Bank (New York: Quartet Books, 1982). ↩

- Retamar, “Caliban,” trans. Lynn Garafola, et al., 10. ↩