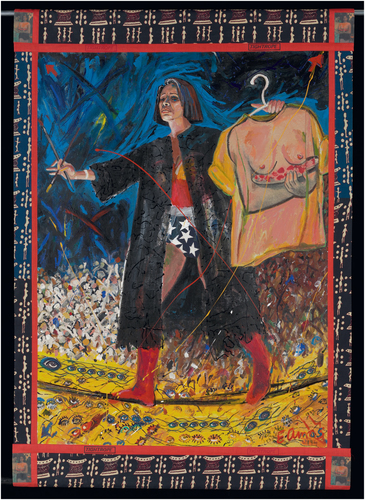

In 1994, at the age of fifty-seven, Emma Amos (1937–2020) painted a full-length portrait of herself as Wonder Woman balanced precariously above a crowd. Her star-spangled leotard beneath a voluminous painter’s smock clearly points to the heroine of the late 1970s television series. In Amos’s Tightrope, the celebrated African American artist holds two paintbrushes in her right hand, and in her left, a hangered T-shirt that depicts a nude torso borrowed from Paul Gauguin’s Two Tahitian Women (1899).1

Earlier in her career, Amos had participated—as the youngest and only woman member—in the African American artist collective Spiral (1963–65) and subsequently had played a role as a founding member of the activist feminist art group, the Guerrilla Girls (1985–). Thus, by the time she painted Tightrope, Amos had more than demonstrated her concern with expanding the art world towards greater inclusion of historically marginalized practitioners, especially those representing Black and female perspectives. In keeping with this mission, and at the height of her artistic career, Amos was now appropriating Gauguin’s figure in Tightrope to critique the late nineteenth-century French artist’s primitivizing of women of color—no less his continued influence on the global contemporary art world.2

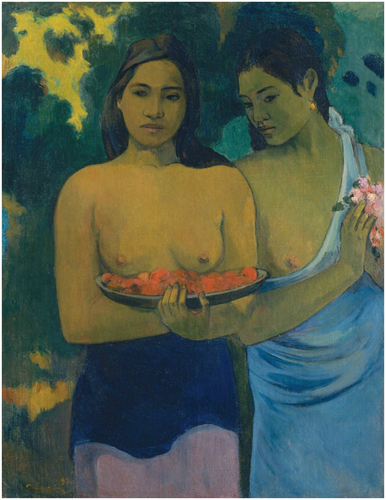

Gauguin’s painting depicts two young, topless South Pacific women standing beside each other, one holding a tray seemingly loaded with fruit (the identification remains uncertain), while the other is clutching a small bunch of flowers. The women are beguiling and beautiful, seemingly innocent in their lack of bodily shame in front of the painter. Yet, they are also seductive in the way they express a cautious curiosity towards the viewer, and in the analogy to be easily made between their offerings and their own exposed breasts and nipples.

Gauguin’s South Pacific paintings have been lauded for advancing continental modernism and, more recently, critiqued for their primitivized depictions of race, gender, and sexuality. Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) was famous for purportedly depicting the Indigenous populations of Tahiti and the Marquesas. However, Gauguin worked at least as much from colonialist photographs as from live models. Art historian Elizabeth Childs identifies about sixty of Gauguin’s Polynesian artworks as appropriating poses or motifs from his collection of ethnographic photographs, and photographic reproductions of works of art.3 Consequently, sources for the artist’s “Tahitian” paintings derive from Indigenous art forms spanning the globe, including ancient Egyptian royal tomb frescos, Indonesian Buddhist temple reliefs, Easter Island tablets, and Maori wooden gateway figures.4 Gauguin’s artworks do not, therefore, simply take motifs from Tahitian and Marquesan culture, but from a colonialist image category of “primitive indigeneity” more broadly. Even during his lifetime, Gauguin was accused of lifting his formal, as well as narrative, innovations from others, fellow painter Camille Pissarro noting in 1893, “Gauguin is always poaching on someone’s ground; nowadays, he is pillaging the savages of Oceania.”5

I contend that Amos’s appropriation of Gauguin is thus more accurately defined as “reappropriation,” an interdisciplinary concept that indicates an affirmative redefinition of a pre-existent example of cultural appropriation. The idea describes when a marginalized group resignifies an expression originally intended to be pejorative into a favorable identification for their community.6 As with the designations “gay” and “queer,” a reappropriated word may have originally held a neutral or positive connotation before it was reduced into a slur.7 With reappropriation, a marginalized group reidentifies a formerly critical comment a third time as an affirming group identifier, though the declaration holds the legacy of its past negativity. Doubly appropriated words thus carry within them a range of possibilities for in-group and out-group use (including positive and derogatory applications) that are not fixed, but always in flux.8 A newly claimed utterance of historical oppression, such as the offensive terms “bitch” and the “n-word” may assert agency when used by, respectively, women and African Americans. Yet the expression’s hateful and dehumanizing history remains even after reclamation.9 Reappropriations thus evoke a quality of ambivalence, as they affirm a marginalized group’s identity while acknowledging (rather than denying or erasing) the pain the group has faced in its historic misrepresentation.

The term “reappropriation” is often applied in sociolinguistics and social psychology, but I propose that it is also useful for analyzing works of art. Visual cultures traffic in an abundance of historical stereotypes, many of which depict marginalized or disempowered groups in demeaning ways. Artists can intervene and critically rework such stereotypes to gain agency in representation, all the while acknowledging past hurt. Artworks employing visual reappropriation demonstrate the potential for restorative self-definition not only linguistically through a renaming, but also visually through re-presentation.

At the time of its creation, Gauguin’s art made little room for women of color as active agents in their own representations. The artist documented little about his subjects, and the resultant gaps in the archives have presented challenges for historians seeking to unearth the voices and perspectives of his colonial subjects. Feminist art historians, in particular, have lamented the limited accounts of the lives and opinions of the women Gauguin represented, including his young Tahitian wife, Teha’amana.10 Gender studies scholars and art historians have also noted the androgyny of Gauguin’s Tahitian figures.11 A Maori scholar has even speculated that some of these figures might be māhū, an Indigenous designation used in Tahiti, Hawai’i, and the Marquesas Islands for gender-divergent persons who embody both masculine and feminine qualities.12 Still, there is limited archival information for identifying what may be non-binary subjects in Gauguin’s art.

An accurate and inclusive art historical process involves grappling with absences in the canon and the archive, especially for figures historically marginalized and disempowered due to gender, sexuality, and race. Critical historiography emerging from Black feminism asserts that a lack of historical records does not indicate historical insignificance. Rather, it denotes the need for alternative methods for giving voice to historically ignored or silenced experiences. These methods include imaginative acts of historical recreation (or “critical fabulation,” in Saidiya Hartman’s words) and attention to embodied knowledge.13

Amos’s reappropriation in Tightrope indicates how women artists of color can reclaim Gauguin’s art to gain symbolic agency in experiences of art world marginalization still impacted by legacies of colonialism. She poses herself as carefully navigating a contemporary art world in which she must grapple with intersectional discrimination.14 Her options are limited to donning Gauguin’s shirt and performing colonialist expectations of alluring primitive feminine sexuality. Or, she may wear the Wonder Woman costume and align herself with white feminists while setting aside her racial identity. A final option is to subsume both her gender and racial identities under the smock of a professional artist, a role so often presumed to be white and male.15 Amos uses Gauguin to visualize her experience of being subjected to a racially and sexually objectifying gaze, one historically rooted in colonialism but still active today. Amos appropriates Gauguin’s paintings as a female African American artist impacted by the history of European primitivized representations of women of color. However, because she is not Tahitian or Marquesan herself, her painting also references Tahiti through Gauguin. Her reappropriation thus carries the ambivalence of both inheriting Gauguin’s colonialist views of Tahiti while also working to resist their primitivist ideology.

Artists with Indigenous heritage in the South Pacific (but not specifically to the Tahitian or Marquesan islands) have added to the critiques of Gauguin’s visions by employing reappropriation.16 Much of this work, like Amos’s painting, uses Gauguin’s art to address continuing colonialist intersections of sexism and racism. For example, artist Tyla Vaeau, who is of Samoan and European heritage, superimposes snapshot photographs of her sister and a friend into his iconic paintings in place of his female subjects’ faces. The women in Vaeau’s pieces make strained, pouty, and annoyed faces, satirically calling into question Gauguin’s presentations of placid, compliant Indigenous feminine sexuality. Vaeau’s intervention is part of a broader growth in twenty-first century Indigenous Pacific art, much of which blends historical references with critical new media practices, including photography and digital media, to look “back in order to move forward.”17 Additionally, feminist artists from around the world have also reappropriated Gauguin to claim agency in modernist presentations of female sexuality.18

Contemporary photographers over the last decade have added a new outlook to the mix of critical approaches to Gauguin’s legacy: the issue of nonbinary gender identity. Their projects claim Gauguin’s work to stage intersections between not only gender and race, but also LGBTQIA+ identity.19 My essay will examine the projects of Namsa Leuba (b. 1982) and Yuki Kihara (b. 1975) to consider what these newer photographic works add to pre-existing feminist critiques of Gauguin.

Leuba and Kihara are two contemporary photographers who each claim Gauguin as a building block for their own photographs of non-binary and trans women of color living in a postcolonial, tropical context. Leuba is a Swiss-Guinean fine art and fashion photographer based in Bordeaux, France. Japanese-Samoan fine artist Kihara, based in Samoa, represented New Zealand at the 59th Venice Biennial (2022). Each photographer has created a series of works that depict members of Tahiti’s and Samoa’s gender-divergent communities (the latter of which Kihara is a member) in lush, colorful scenes that reimagine Gauguin’s paintings.

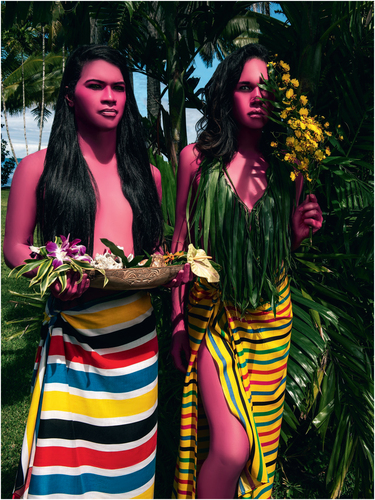

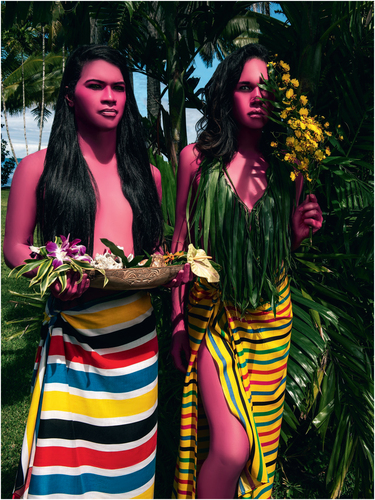

For example, both Leuba and Kihara reappropriated Gauguin’s Two Tahitian Women in 2019 and 2020 in photographs they made (independent of each other) by working with Tahitian and Samoan models. These images echo Gauguin’s originals in their focus on Polynesian women’s and gender-divergent people’s sexuality. “Gender divergent” is a generalist phrase that can distinguish Indigenous sexualities from Western designations of “transgender,” “transsexual,” and “homosexual.”20 I use “gender divergent” in this essay to indicate the similarity in Tahitian and Samoan beliefs that gender embodiments can express both femininity and masculinity. However, I will also address each culture’s distinct terminologies for gender-divergent populations.

I consider Leuba’s and Kihara’s photographic reworkings of Gauguin as examples of reappropriation, even though Leuba and Kihara are not direct descendants of Indigenous Tahitians or Marquesans. This aspect of their identities could raise concerns that their photographs risk recreating exploitative appropriation rather than reappropriation. Such apprehensions are warranted considering the history of colonialism’s objectifying gaze and the absence of Tahitian and Marquesan outlooks in most exhibitions of Gauguin’s art.21 As with Amos’s painting, their photographs ambivalently recall Gauguin’s colonialist legacy, while also critiquing it.

Gauguin’s paintings were not merely representations of Tahitians or Marquesans but poached a range of imagery from colonialist photographs. As women of color, Leuba and Kihara are negatively impacted by the broad colonialist ideas about the primitivity of people of color that undergird Gauguin’s art. Thus, Leuba and Kihara are postcolonial artists reappropriating Gauguin’s colonialist imagery. Their reparative work involves inviting their subjects to collaborate in the artmaking process, such subjects thus gaining a measure of agency and empowerment. Leuba has discussed the importance of developing relationships with her subjects before photographing them and presenting them as “they would want viewers to see them.”22 Kihara also explains that she made her photographic series Paradise Camp (2020–) for members of Samoa’s gender divergent community, who are referred to by the regional Indigenous term fa’afafine (women identified as male at birth).23 As Kihara recently stated of the series, “I want to use [Paradise Camp] to build fa’afafine capital.”24

Leuba and Kihara wield photography to critique the ideological constructions behind Gauguin’s modernist primitivist painting. Unlike Amos, whose career developed during a period when success still meant breaking into the ranks of canonical modernist painters—in other words, primarily white male practitioners—Leuba and Kihara came of age when postmodern strategies of conceptualism and appropriation were challenging modernist ideals. Photography and video (rather than painting) were primary media of choice for much of this work.25 These two artists’ use of the photographic medium indicates their postmodern critique of the modernist ideals of Gauguin’s painting.

In keeping with this strategy, Leuba’s and Kihara’s photographs balance awareness of the continued legacies of European primitivist fantasies born in colonial and sexual encounters, with a celebration of the strategies used by marginalized groups to assert control over the construction and presentation of their own identities—the latter most often manifested in acts of theatricality, camp, and drag. I assert that Leuba’s and Kihara’s reworkings of Gauguin build coalitions across distinct populations with shared experiences of marginalization and sexualization under Eurocentrism. Their photographs thus demonstrate the value of an intersectional transfeminist outlook for the creation of a revisionist art history.

Docu-fictions

As an Afro-European woman of color, Namsa Leuba is keenly aware of European racial and cultural perceptions. Leuba grew up in Switzerland, her father’s country of origin, but she often visited Guinea, her mother’s home country, where the artist continues to have extended family. Much of Leuba’s photography addresses issues of identity and mythology in European and African encounters in a postcolonial world. For her photographic series Illusions (2017–23), Leuba considers a postcolonial legacy from another context: the iconic paintings of Tahitian and Marquesan women by Gauguin. As a young art student, Leuba remembers her father giving her a book of Gauguin’s paintings, which inspired her aesthetic development.26 She returned to Gauguin’s works in 2017 after moving temporarily to Tahiti (she would stay for two years) to photograph the islands’ gender-divergent population.

Like many contemporary European travelers to Tahiti, Leuba arrived on the islands well-versed in Gauguin’s imagery and its complicated reception. Gauguin stands as a foundational figure for modernist painting even while his reputation carries suspicions of cultural appropriation and sexual exploitation.27 His art sits in major art collections and is the subject of regular traveling exhibitions and scholarship.28 He is included in art historical surveys of Western and global art, such as the core 250 “required images” of the Advanced Placement (AP) art history curriculum—and accompanying exam—for US high school students.29 Some of Gauguin’s most influential art was made in Tahiti after he quit Europe for the South Pacific in 1891. Gauguin sought to escape modern civilization for a so-called primitive existence in nature, an expectation he had formed from consuming European literature and photography addressing Polynesian life and love.30 Later coming to feel that Europe had overly influenced Tahiti, Gauguin removed himself to the Marquesas Islands in 1901, where, settling on the island of Hiva-Oa, he sought new models and a “more savage subject” matter.31 Once resituated, Gauguin continued to paint until his death in 1903. Although Gauguin ostensibly sought change in his surroundings, the Marquesas Islands paintings are similar to the artist’s Tahitian works in both their subject matter and style of rendition.32 Gauguin’s depictions of Tahiti and the Marquesas—including paintings of the young women with whom he had sexual relations—would, in turn, shape ideas back in Europe about French Polynesia in general and invigorate avant-garde interest in the creative traditions and sexuality of colonized peoples.

Starting in Gauguin’s own lifetime, observers of what the artist shipped back to Paris expressed concerns that his South Pacific scenes presented problematic approaches to race and sex, while appropriating formal innovations of the cultures he infiltrated. By the late twentieth century, feminist art historians expanded such critiques. Abigail Solomon-Godeau demonstrated that Gauguin’s productions evinced “plagiarisms” of European texts and photographs he had encountered before embarking on his travels, further accusing Gauguin of failing to demonstrate anything authentic about his encounters with his female subjects.33 Griselda Pollock analyzed Gauguin’s formal choices as coding fetishized and comprising touristic fantasies of “sexual and racial difference” calculated to increase his art’s value within a capitalist European art system. Additionally, Pollock did not shy from castigating the middle-aged, syphilitic artist for his intimate relationships with young Indigenous women of the South Pacific, all while supporting a wife and family in France.34

One might have expected such arguments to have ultimately “canceled” the artist, as a New York Times report of a Gauguin exhibition at The National Gallery, London, in 2019, suggested.35 Gauguin’s art, however, continues to speak to audiences. One element of its enduring legacy may be its depiction of subjects otherwise absent from, or on the margins of, European modernism.36 These include representations of women of color and androgynous expressions of gender. As scholars have noted, Gauguin depicts Tahitian and Marquesan women with broad waists and shoulders, and large hands and feet that contrast with the European late nineteenth-century ideal of the wispy lady.37 Rather than “cancel” this artist, then, Leuba, Kihara, and others have reappropriated Gauguin’s iconic appropriations to expand and build upon the limited modernist traditions of representations of non-European and gender-divergent peoples.

Leuba initiated her project on the heels of a growth of trans visibility and controversy in popular culture. Early twenty-first century media introduced several trans characters and trans-themed television programs. Trans celebrities also gained prominence in popular media, and LGBTQIA+ visibility expanded across the internet.38 Political backlash to these developments has also arisen. For example, many American state legislatures have passed bills in recent years that limit protections for trans people in public accommodations such as access to community bathrooms and healthcare.39 Additionally, recent American executive orders have defined gender as binary and immutable and directed federal agencies to roll back protections for trans people, as well as deny funding to entities that support gender-affirming care.40 Leuba’s project also developed just after Polynesian LGBTQIA+ communities began to formally organize—starting in the early 2000s—to achieve greater recognition and civil rights.41 Such developments, both regionally and globally, resulted in local Indigenous gender-divergent communities gaining activist outlooks and a new vocabulary inspired by their affiliation with global LGBTQIA+ groups. For example, the advocacy efforts of the Samoan Fa’afafine Association recently shifted to also advocate for fa’afatama (men biologically identified as female at birth), who are even more marginalized in Samoa than the fa’afafine.42 These organizations represent distinct historical Indigenous identities from different islands, which is captured by the new umbrella initialism MVPFAFF+ (māhū, vakasalewalewa, palopa, fa’afafine, akava’ine, fakaleiti/leiti, and fakafifine+).43

Academic scholarship over the last few decades has also emphasized the importance of queerness and non-binary gender identity to understanding Gauguin and the history of Euro-Polynesian encounters. Art historian Stephen Eisenman presented a lengthy Gauguin study in 1997 arguing that the artist pursued gender and racial ambiguity in both his personal identity and art as part of a broader desire for liberation from European bourgeois norms.44 Lee Wallace interprets Gauguin’s paintings of androgynous Polynesian women as foils for the artist’s ambivalent “male-male sexual interest,” reading Gauguin’s primitivism as indicating a desire for queerness. In support of this theory, Wallace connects colonialist travel narratives by Gauguin and others that describe Polynesia’s history of acknowledging more than two genders as essential to the development of modern European and American ideas about male homosexuality. In addition, he argues that much recent European scholarship (including feminist accounts by Solomon-Godeau and Pollock) disavows the importance of queer desire in Euro-Polynesian interactions, as well as the reciprocal influence both cultures had on each other’s ideas about sexuality.45

Once she situated herself in Tahiti, Leuba began her project by meeting with writer Francois Bauer, author of Raerae de Tahiti (Rae-rae of Tahiti), published in 2002.46 A term referring to regional Indigenous trans persons, rae-rae was introduced to the Tahitian language in the 1960s when male-to-female gender transitions first became medically possible through hormone therapy and surgery.47 This newer designation is distinct from the older māhū, which predates European contact. The Indigenous populations of Tahiti, the Marquesas Islands, and Hawaii use māhū to refer to gender-variant individuals who embody both male and female qualities.48 In Tahiti, the word has historically pertained to effeminate men.49 Tahiti holds strong civil rights protections for MVPFAFF+ peoples, including legally recognized same-sex marriage, and acknowledgment of their social status as a class protected from discrimination. Bauer introduced Leuba to rae-rae and māhū Tahitians whom the artist interviewed and invited to model for her photographs. Through her discussions, Leuba learned that some of her participants had faced homelessness and family estrangement, while others were readily accepted by their communities. Some models had even been photographed earlier by social documentarists, but those works had emphasized the sitters’ marginalization, disempowerment, and victimization.50 Social documentary photography aims at exposing truths, but its images often present a limited and even biased perspective that is taken as fact.51 Leuba was interested in staging a different, more open-ended kind of encounter.

Leuba identifies her photographic process as “docu-fiction.” The descriptor acknowledges the photographic medium’s indeterminate status as both a documenter of reality and a constructor of deceptions. As she describes it, her works do not present themselves as capturing the truth of Tahiti and its gender-divergent community, but a truth about her subject.52 Leuba titled her series of Tahiti photographs Illusions. Here, she acknowledges her photographs’ own status and points to the history of Western myths of the Pacific, including Gauguin’s own paintings, which were a mix of real and imagined experiences. In France, Gauguin marketed his art as capturing an authentic connection with primitive Tahitians. Still, while painting in Tahiti, he turned for visual inspiration to a range of colonialist travel photographs that circulated in Western popular culture and World’s Fair exhibitions.53

An apt example of this is provided by Gauguin’s Two Tahitian Women, which Amos quoted, and which Leuba and Kihara both recreated. Elizabeth Childs has revealed that the artist borrowed some of his iconography in this instance from a photograph of temple reliefs in Borobudur, Java, which depict a topless woman offering up a tray of flowers to a voyager visiting the temple from afar.54 Gauguin’s painting is thus as much a painterly dreamscape inspired by a Javanese photograph as it is derived from any firsthand encounter in Tahiti. The artist had traveled nearly ten thousand miles to escape “civilization,” though he continued to rely upon elements of its visual culture to construct his artworks.

In partial self-conscious response to Gauguin’s tableau, Leuba’s L’Offrande (The Offering), of 2019, reworks Two Tahitian Women into a meditation on truth and illusion. As a photograph, it depicts real individuals whom the photographer encountered: two rae-rae who wear colorfully striped sarongs. One figure holds a wooden bowl carved with traditional Polynesian motifs, which bears tropical offerings from land and sea: orchids and anthuriums, coral and shells. The image was shot in sharp focus, and its defined edges and strong value contrasts wrench Gauguin’s scene out of its original, flattened, dreamlike setting. Yet, Leuba self-consciously stages her subjects in a fantasy context of tropical overabundance. Her subjects wear sarongs with intensely saturated stripes of color. The clothes hang loosely as if the models are ready to undress, possibly for a swim, at any moment. Their bare chests are covered only by long, shiny black hair or palm fronds, recalling familiar historical touristic imagery of hula skirts and tiki girls. Unexpectedly, both figures are decorated with hot pink body paint. The intense color echoes the saturated shades of fabric and the hues of the tropical flowers carried ceremoniously by one of the figures. The radically unnatural skin tone prevents the photograph from being read as an authentic documentary or touristic image of tropical women in situ; instead, the painting signals its own status as a constructed fantasy.

Leuba does not expose her subjects’ natural skin colors in any of the Illusions series photographs. Instead, she realigns their complexions with natural hues associated with the islands’ waters, plants, and skies. The overall series exhibits a rainbow of skin tones. The intense palette draws attention to the fact that race is an important factor in fantasies of what most defines tropical identity. The luminescent colors all but cancel Gauguin’s original association of exoticism (and attendant eroticism) with the brown skin of his subjects. Leuba asks her audience to think more critically about the historical role of race in primitivist imagery like Gauguin’s, while at the same time celebrating colorful skin. Leuba’s resplendent tones suggest that identities presumed to be innate—like race and gender—are socially constructed and performative.

Leuba also shifts her subjects’ gazes upwards in ways that indicate a newfound personal agency not apparent in Gauguin’s picture. Indeed, the figures in Gauguin’s Two Tahitian Women seem submissive to an outside viewer’s sexualizing stare. Notably, neither figure is looking directly at the viewer; the woman on the right has even partially turned her head, as if out of innocence and shyness. By marked contrast, the women in L’Offrande hold their heads higher than Gauguin’s, their chins noticeably lifted rather than tucked downward. Unlike the original subjects’ placid compliance, these women’s heavily shadowed eyes communicate a steely strength. The figure on the right covers half her face with a branch of Dancing Lady orchids. Her other eye, more heavily in shadow, pierces the viewer, its visibility made even more prominent by her light blue contact lenses. These women’s gazes also communicate—despite their hint of agency—guarded restraint and intense observation. They hold critical awareness of the power relations between subject and viewer.

With her emphasis on dazzling colors and gestures of hide-and-seek, Leuba’s photograph evokes the aesthetics of drag. In contemporary Tahiti, drag shows and pageants are regularly performed.55 While the defining parameters and meanings of drag have shifted in culturally and historically distinct times and places, drag is generally understood to involve an exaggerated performance of binary gender codes applying to male and female gender identity—fashion, hair, makeup, physical postures and gestures, voice intonation, and so forth—that may also engage comedy, song, and dance.56 Following Judith Butler’s use of drag to establish her theory of gender performativity in her 1990 publication, Gender Trouble, drag became key to many academic studies that called gender essentialism into question.57 In these studies, drag has been read as radical and liberating. But drag has also been popularized in recent decades in mass media forms and entertainment venues, such as the popular US reality television competition RuPaul’s Drag Race. Thus, drag has somewhat paradoxically also been regarded as conformist in nature—especially when performers of color compete in such pageants to adopt ideals of white femininity propagated by colonialism.58 As with reappropriation, drag involves a marginalized group resignifying cultural symbols (here, of Western notions of essentialized binary gender identity) that can also function to exclude or disempower the group. Drag (like reappropriation) therefore carries a range of creative and interpretive possibilities (including positive and derogatory applications) within it.

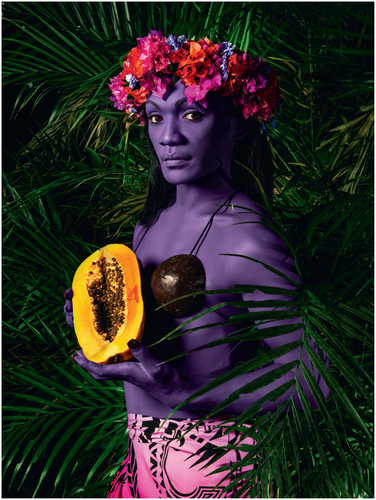

The artificial skin tones in L’Offrande accommodate the diverse historical perspectives of drag. Leuba’s approach both recreates aspects of Gauguin’s gendered exoticism and colonial fantasy, while also working to denaturalize his essentialist visualization of race. To consider another example, Leuba has also reappropriated Gauguin’s Vahine no te vi (Woman of the Mango), of 1892. In Gauguin’s painting, a young woman wears a deep purple Western dress. She looks off to the side, seemingly unconcerned with the viewer and unaware of the sexualized symbolism of the mango in her hand. And in Leuba’s La Femme à la Papaya IV (Woman with a papaya IV), of 2019, Leuba paints her subject’s muscular chest and strong, manicured hands in the same rich tone as Gauguin’s dress. Here Leuba strips away the Western attire, dressing her rae-rae model in a stereotypically tropical ensemble: coconut shell bra, South Pacific sarong, and floral crown. The model’s sleek purple skin stands out vividly against the sharp, green palm leaves, drawing in the viewer’s eye and activating a haptic sense of touch. Unlike Gauguin’s model, who seems unconcerned with the viewer, Leuba’s figure engages directly with the audience, locking eyes with those who gaze at her while she presents the cut-open papaya—its flesh and seeds exposed for display. Like a drag performer, Leuba’s model seems aware of the theatrical nature of her interaction with the audience. Her exaggeration of seemingly natural gender and racial expressions directs the audience to recognize how such qualities are socially constructed. Leuba has transformed Gauguin’s more coded sexualizing of a fully clothed model into a photograph self-consciously performative of desire.

After Gauguin

Samoan multimedia artist Yuki Kihara reappropriated twelve of Gauguin’s paintings in a series of photographs of Samoa’s fa’afafine community for Paradise Camp, her exhibition for the New Zealand national pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennial (2022). Even though Gauguin never depicted Indigenous subjects from New Zealand or Samoa, Kihara’s critical reworkings of the French artist’s South Pacific paintings are relevant to the Indigenous populations of both countries. Gauguin did visit New Zealand once, in August of 1895, where he sketched Maori treasures in Auckland’s art galleries and museums for inspiration.59 Although he never visited Samoa, Gauguin utilized colonial photographs of the country’s people and sites as source material.60 Thus, his paintings reflect influences from New Zealand and Samoan Indigenous societies. Kihara’s Paradise Camp accordingly restages Gauguin’s art to address generalist Western colonialist and touristic fantasies of Indigenous Polynesian populations that—as in Gauguin’s own paintings—often do not distinguish between the unique cultures and traditions of distinct islands.61

Kihara herself identifies as fa’afafine, thus adopting the Samoan descriptor for non-binary individuals. The term translates into English as “in the manner of a woman,” expressly designating females who had been biologically identified as male at birth. Fa’afafine is one of the four culturally recognized genders in Samoa, alongside female, male, and fa’afatama, meaning “in the manner of a man,” or denoting men who had been biologically identified as female at birth. Although these four genders are culturally recognized, only male and female genders are acknowledged in Samoan legislation. Samoa therefore offers significantly fewer civil rights and protections for MVPFAFF+ individuals than Tahiti. The country does not legally recognize same-sex marriage, and sodomy remains a crime, even though the law prohibiting it is not regularly enforced.62 Partly in response to such social and political conditions, Kihara asserts that she is “driven to create work that empowers an audience,” and that Paradise Camp was specifically made for the fa’afafine and fa’afatama communities.63

A multi-platform contemporary artist, Kihara has created bodies of work in a wide range of media, including photography, film, and mixed media, in attempting to address the history of gender-divergent Polynesian identity and its depiction in colonialist imagery. Her work often recreates examples of modern art, and nineteenth and early twentieth-century photographs of scantily clad women. Her sources exhibit the “dusky maiden,” a colonialist construction of Polynesian women as sexually alluring, but also innocent and guileless.64 As a woman of Indigenous heritage who often employs herself as her subject, her works repurpose such examples of stereotyped portraiture to examine how power informs identity, especially in the wake of colonialism.

Like Leuba, Kihara is of mixed national and racial parentage, her mother Samoan, her father Japanese; consequently, she grew up in Samoa, Japan, and New Zealand. Kihara therefore shares with Leuba experiences of biracial and multinational identity. This background informs her interest in the cross-cultural, Euro-Polynesian legacies of Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings. As a fa’afafine artist of color, Kihara experiences intersectional identity as both a racial and gender minority in the fine art world. And like Leuba—and Emma Amos, as is evident in Tightrope—she finds Gauguin’s works to be fruitful ground for reflecting on this experience. Kihara has the added dimension of being an MVPFAFF+ artist, and her intersectional condition thus encompasses aspects of race, gender, and sexual identity.

Kihara sees herself as being in conversation with Gauguin across the centuries. She states that she and Gauguin are “artists from two different parts of the world having a dialogue in two different moments in art history.”65 Her emphasis on “moments in art history” indicates that Kihara is not looking to Gauguin for ahistorical aesthetic influence, but that she is reassessing his legacy from the perspective of today’s socio-political stakes. Her approach is well-versed in Western art history, including conceptual art’s critical focus on the role of language in fine art, and dadaist traditions of appropriation originating in Marcel Duchamp’s readymades, as well as the strategies of 1980s Appropriation Art, when artists like Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince rephotographed iconic imagery as their own. Inspired by postmodern thinking, including Roland Barthes’s “The Death of the Author,” their works staged questions such as, “Which of these renditions is more truthful, authentic?” and “What is authorial originality in the context of capitalist exchange and its expansive photographic visual culture?”66 Kihara’s reappropriations thus reflect a distinctly ironic, postmodernist approach toward dismantling modernist mythologies informing seemingly neutral language and imagery.

Kihara challenges Gauguin’s historical authority by appropriating and updating his images. Her works announce themselves as reappropriations of Gauguin by making their repetition obvious in both their imagery and titles. Her Two Fa’afafine (after Gauguin), of 2020, for example, closely resembles Two Tahitian Women. Kihara’s models are posed in nearly identical formation to Gauguin’s, and they retain their natural skin color. Their sarongs drape similarly as in the nineteenth-century example, and they hold props like those found in Gauguin’s work. The lush, tropical forest background is also flattened by Kihara like the abstract shadows of the earlier painting, with the many crisscrossing leaves and trunks cancelling any establishment of a larger depth of field.

Whereas Leuba’s reappropriation of Two Tahitian Women in Two Fa’afafine self-consciously emphasizes artifice to denaturalize Gauguin’s fantasies, Kihara leans into a dry and cerebral sense of irony. Her titles express a deadpan quotation that calls the value of traditional concepts of originality into question. She continues throughout the Paradise Camp series in this manner, modeling each piece on a specific Gauguin work. She titles each work with an English translation of the original French (or something quite close to it), adding to the end of each title, in parentheses, “after Gauguin.” Several of her recreations replace Gauguin’s use of a French feminine noun in the original title—such as “Tahitienne” or “femme,” or the English translation “woman,” by which the work has come to be known today—with the Indigenous gender variant descriptor “fa’afafine.”67

Kihara’s use of the originality disclaimer, “after Gauguin,” makes obvious to the viewer that Gauguin inspired the works, given that “after” suggests a subsequent execution “in the manner of” a chosen, “master” model. Notably this phrasing evokes the common translation for fa’afafine: “in the manner of a woman.” Kihara’s titling thus relates her adoption of Gauguin’s identity to the adoption of feminine gender characteristics. Both forms of identity—artistic/authorial and gendered—are thereby proposed as a series of signs that one can perform. The art world knows Gauguin through his most iconic pieces; other artists can copy his look to indicate “Gauguin-ness.” Kihara’s titling ultimately suggests that both Gauguin’s iconic style and what is culturally accepted as “feminine” can be replicated.

Kihara’s work evokes a campy sensibility. Historian George Chauncey defines camp as originating in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Western culture, a time during which gay men felt the necessity to lead double lives.68 Their use of double entendres, irony, and humor enabled a play both with and against dominant social codes. Gay men enacted subcultural signs of women’s culture to make space for the gay community within pre-existent heteronormative society. Drag balls were an extreme version of this, which parodied the practice of debutante balls for young women “coming out” into society.69 Definitions of drag and camp vary and overlap, but generally, drag is considered to be an exaggerated performance of gender codes, whereas camp is more broadly defined as an aesthetics of artificiality that can be used to both hide and reveal identity, and is often aligned with queer culture.70

Kihara references campiness directly in her exhibition’s very title: Paradise Camp. On the one hand, the “camp” of her title recalls the temporary habitations (such as tents or other encampments) of travelers who come to Samoa and other South Pacific islands on vacation, expressly looking for the exoticism depicted in Gauguin’s paintings. Yet, the term “camp” also references queer aesthetics.71 Thus, Kihara’s use of “camp” in the title is itself “both, and”—in other words, it can code within heteronormative culture while also speaking against it.

Two Fa’afafine (after Gauguin) has this campy “both, and” quality. The image closely mimics the language of Gauguin’s original, while it also represents fa’afafine bodies. The artist exposes the flat chests of her fa’afafine models, proposing a non-binary challenge to Gauguin’s original. This tactic contrasts with that employed by Leuba in L’Offrande, which teases the viewer by covering her models’ chests with hair and palm fronds. The two artists’ reappropriation strategies overlap, but Kihara’s is more dryly campy, whereas Leuba’s goes full drag.

Yuki Kihara, Paul Gauguin with a Hat (after Gauguin), 2020, chromogenic print, 17½ x 15 inches (45 x 38 cm), from exhibition Paradise Camp, curated by Natalie King and commissioned by The Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa for the Aotearoa New Zealand Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale, 2022; (artwork © Yuki Kihara; photograph provided by Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Dunedin, New Zealand)

Paul Gauguin, Portrait de l’artist (Self-Portrait with Hat), 1893–94, oil on canvas, 18 x 15 in. (46 x 38 cm), Musée d’Orsay, purchased with the participation of an anonymous Canadian donor (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by Art Resource)

This difference in tone between the two artists evokes their distinct approaches to MVPFAFF+ visibility. Leuba draws more on traditions of drag performance that originate in the West but that have since been adopted in both Tahiti and Samoa. Lacking many of the rights and protections enjoyed by the MVPFAFF+ community of Tahiti, Samoa nonetheless decriminalized “female impersonation” in 2013, enabling fa’afafine to perform in drag without fear of legal prosecution. In general, fa’afafine activism has involved less direct radical action than that often seen in Western contexts, and it embraces more of what one sociologist has characterized as “a gentle politics of recognition and persuasion.”72 Fa’afafine purposely involve themselves in Samoan community life, contributing acts of service to churches and other institutions to share their skills and gain visibility and acceptance within existing societal institutions.73 Two Fa’afafine (after Gauguin) carries more of this tone of “gentle insertion” of fa’afafine identity into a pre-existing structure, whereas Leuba’s L’Offrande reads more as extravagant theater.

Though her artworks are generally transparent about the identity of their models, Kihara engages in gender masquerade in her work, Paul Gauguin with a Hat (after Gauguin), of 2020. She modeled this piece on the French artist’s 1893 canvas Portrait de l’artist (Self-Portrait with Hat), which Gauguin painted in his Paris studio after returning from his first Tahitian sojourn (1891–93). Gauguin presents himself with signs of his exotic travels. He wears a wide-brimmed hat apt for blocking the tropical sun, and behind him are his travel valise and his painting Manaò tupapaú (Spirit of the Dead Watching), of 1892, which depicts his Tahitian wife, Teha’amana, as he once encountered her lying naked in the couples’ bed.74 Kihara reappropriated Gauguin’s provocative work by inserting herself in the position of the painter. To accomplish the switch, she undertook an hours-long makeup session that included the addition of prostheses to transform herself into a Gauguin lookalike.75 She dresses like the artist, wearing a wool suit and a wide-brimmed, woven grass hat. Kihara’s rendition replaces the painting in the background of the original with a reproduction of siapo, an Indigenous Samoan craft of painted bark cloth with geometric patterns resembling local flora and fauna.76 This substitution of a patterned background for the original painting of the nude steers the artwork’s focus on Kihara’s physical appropriation of Gauguin’s self-image and highlights an example of Indigenous art—the craft of siapo—replacing Gauguin’s objectifying portrait of his young wife. It also renders an artistic self-portrait as always staged, that is, not constituting an authentic capture of one’s true self.

In the original painting, Gauguin poses himself in a liminal space between acting as the European, civilized citizen, and the voyager who has “gone savage.” His eyebrows and forehead relax, and he maintains the critical gaze of a professional artist studying oneself in a mirror. However, he also depicts his adoption of Tahitian culture via accessories that he can choose to hold close or remove from proximity—a hat, a bag, a painting.

Kihara’s portrait also presents herself as navigating two distinct realms, but via embodiment. She does not frame herself as a liminal traveler like Gauguin, who demonstrates his ability to move at will between two worlds via his acquired and exhibited objects. Rather, she wedges herself into a shallow box that allows for little movement, suggesting her status as an artist of Indigenous heritage working in an art world traditionally dominated by narratives of Western art history. Though girded by a literal background of Indigenous heritage, her self-presentation nevertheless involves a highly skilled process of layering onto her body distinct national, racial, and gender identities. The thick makeup and prosthetics suggest a visible externalization of an inner artistic identity influenced by the overlapping, but conflicting, historical experiences of colonial artists and postcolonial subjects. One cannot help imagining these layers of influence as weighing her down. Nevertheless, Kihara subtly tilts back her head and returns the viewer’s gaze at a downward angle. Even though her body is on display, she lifts and furrows her brow as if critically assessing the viewer. Her work acknowledges the viewer’s desire to look upon her unique experience of embodiment, while it also emphasizes her delivery of an oppositional gaze in return.77

When Kihara takes Gauguin’s racial and gender identity for herself, she plays on the history of cultural tensions around passing for a gender or race other than what one was identified at birth. In fact, Kihara cites the influence on her work of recent scholarship suggesting that Gauguin might have been tricked into painting māhū (gender-divergent persons) whom he naively regarded as women.78 The generalized fear of passing’s “trickery” especially impacts trans and non-binary populations of color, whom scholar C. Riley Snorton identifies as activating a crisis of visibility.79 Societal fears of others “passing” as such can evoke anti-trans violence, as in suspicions of trans women deceiving straight men into unwanted, queer sexual situations, or their alleged infiltration of women’s bathrooms to commit acts of sexual abuse.80

Kihara counters such biased concerns about passing with campy irony. In Paul Gauguin with a Hat (after Gauguin), Kihara is fa’afafine passing as a man. Additionally, she is a Polynesian passing as a European. Yet, as some scholars have argued, Gauguin himself played at passing, both as an Indigenous Tahitian “savage” and as a “feminized” man or māhū who sported long hair while residing in the tropics—something Eisenman has read as a drag performance.81 Kihara’s photograph thus could be understood as: a Polynesian passing as a European passing as a Polynesian, and a fa’afafine passing as a man passing as a māhū. As such, Kihara’s photograph denaturalizes the common belief in authentic identity and fear of passing’s trickery to suggest that portraying the self always involves levels and layers of mimicry.

Questions of visual authenticity are important to photography because audiences often assume photographs offer a truthful replication of reality. Kihara’s parenthetical addition to her titles—“after Gauguin”—reminds viewers that photographic imagery often models itself on socially constructed expectations based on pre-existing imagery, including painterly fantasies. Likewise, Leuba acknowledges with her category of “docu-fictions” that photographs are as biased, visually manipulated, and staged as other forms of visual media. Photographs carry a tension between their purported truthfulness and their capacity to engage in powerful deception. By reappropriating Gauguin’s colonialist paintings into photographs of gender-divergent, MVPFAFF+ identifying persons, Leuba and Kihara interweave the instabilities of photography, gender, and race. Each reads as naturally visualizing self-evident truths, though each is constructed. Leuba and Kihara denaturalize photography, gender, and race in various ways that emphasize the ability to retain embodied visual pleasure and critical distance while breaking down visual stereotypes inherited—often unwittingly—from the past.

Revisioning Art History

Despite the androgynous and queer elements in Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings, feminist and queer studies scholars have not always been open to including gender-divergent perspectives in their revisionist histories. As Pollock has quipped in regard to her interpretations of Gauguin’s paintings of desirable Tahitian women, “Am I obliged to adopt the forms of professional transvestism normally required of woman scholars . . . ?”82 Pollock’s work has expressed a feminist discomfort with Gauguin’s male gaze and bemoaned a historical lack of interest in and respect for women’s perspectives. Yet, her incredulity at undertaking an alleged forced scholarly “transvestism” tellingly expresses discomfort with and dismissal of nonbinary and queer viewpoints. Though scholars Eisenman and Wallace center queer looking in Gauguin’s art, they largely emphasize male-male desire, their work stopping short of delving into how a gender-divergent perspective might open new readings of the art, such as in presenting opportunities for female-female desire, including queer desire between cis-female, nonbinary people, and trans women. Leuba and Kihara’s photographs suggest this broader field of erotic potential in the current historiography.

Leuba and Kihara’s artworks affirm a link between queer and feminine perspectives and validate the importance of transfeminism for feminist art history. As defined by Emi Koyama, transfeminism recognizes that the liberation of trans women and non-trans women is inextricably connected across comparable experiences of sexism. It emphasizes intersectionality (rather than a hierarchical ranking of types of oppression) by recognizing that discrimination impacts multiple forms of identity, including race. It does not regard the marginalization of people identified as female at birth as exceeding other types of discrimination (based in race, social class, sexuality, disability, and so forth).83 Gauguin’s own paintings and writings sexualized and exoticized both women and gender-divergent Polynesians. Through their deployment of reappropriation, Leuba and Kihara replace examples of women in Gauguin’s work with models who identify as MVPFAFF+. Across these identity groups is a similar experience of disempowerment in the modern colonialist system. As Leuba has commented, she identifies with her models through sharing a “common experience . . . with the rae-rae subjects related to the experience of living as a woman and everything that entails.”84 Leuba’s and Kihara’s photographs align groups in solidarity through their shared historical marginalization.

In foregrounding gender-divergent people, as well as drag and camp, Leuba’s and Kihara’s reappropriations not only intervene in the history of Gauguin’s art but also demonstrate the value of inclusivity and intersectionality for the writing of a truly revisionist, feminist art history. Emma Amos’s Tightrope parodied Gauguin’s primitivist visions of Tahitian women as like a T-shirt that she could wear to visualize the art world’s biased expectations for women of color.85 Similarly, Leuba’s and Kihara’s photographs evoke an embodied performance of drag and camp to denaturalize and destabilize Gauguin’s myths (and, to an extent, also the broader Western art world’s) about the sexual lives of colonized peoples. Collectively, the work of these three artists affirms that in reappropriating colonialist iconography, opportunities exist to attend to the perspectives and experiences of a broader range of previously marginalized groups, including not only women, but also gender-divergent peoples of color. Their related strategies of reappropriation suggest that one can address problematic modernist legacies like Gauguin’s by building alliances across a wide range of impacted groups to remember and revision the past into new futures.

Mary Trent is an assistant professor of art and architectural history at College of Charleston. She is a co-editor of Diverse Voices in Photographic Albums: “These Are Our Stories” (Routledge, 2022) and has published papers on memory and identity in African American photography and on American artist Henry Darger. [The College of Charleston, 66 George Street, Charleston, SC 29424, trentms@cofc.edu]

I would like to thank Rebekah Compton, Brigit Ferguson, Katie Hirsch, Yuki Kihara, Namsa Leuba, Marian Mazzone, Derek Conrad Murray, Tara Prakash, Barry Steifel, Jessica Streit, Jeffrey Youn, and my anonymous reviewers and editors of Art Journal for their invaluable help with this manuscript.

- While Gauguin’s painting has been known in French and English by different titles, including Deux Tahitiennes (as listed in the catalog of the Salon d’Automne, Paris, of 1906), I am adopting in this essay the English version cataloged by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, where the canvas was acquisitioned in 1949; see the museum’s digital entry, accessed April 29, 2025. ↩

- See Phoebe Wolfskill, “Love and Theft in the Art of Emma Amos,” Archives of American Art Journal 55, no. 2 (Fall 2016): 46–65; for a self-authored statement attesting to Amos’s work having “often taken shots at assumptions about skin color and the privileges of power and of whiteness,” see Emma Amos – Artist, accessed May 18, 2025. ↩

- Elizabeth Childs, Vanishing Paradise: Art and Exoticism in Colonial Tahiti (University of California Press, 2013), 95. ↩

- Bronwen Nicholson, Gauguin and Maori Art (Godwit Publishing, 1995), 16–17, 20–21, 23, 57–59. ↩

- See Camille Pissarro, Camille Pissarro: Letters to His Son Lucien, ed. John Rewald (Pantheon, 1943), 221. ↩

- Adam Galinsky, Kurt Hugenberg, Carla Groom, and Galen Bodenhausen, “The Reappropriation of Stigmatizing Labels: Implications for Social Identity,” Psychological Science 24, no. 10 (2013): 2020–29. ↩

- Though less recognized, apparently the n-word pre-existed its use as a slur against African Americans in the early nineteenth century, namely as a seventeenth-century descriptor for a racial and labor category; see Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor, “The Etymology of Nigger: Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North,” Journal of the Early Republic 36, no. 2 (2016): 212. Also, many insults against women or female body parts (bitch, bunny, fox, cow, pussy) began as neutral terms for animals, with sexism and speciesism influencing the appropriation of such words to denote women as lesser beings—which men could own and use for their own interests; see Piers Beirne, “Animals, Women and Terms of Abuse: Towards a Cultural Etymology of Con(e)y, Cunny, Cunt and C*nt,” Critical Criminology 28, no. 3 (2020): 327–49. ↩

- Robin Brontsema, “A Queer Revolution: Reconceptualizing the Debate Over Linguistic Reclamation,” Colorado Research in Linguistics 17, no. 1 (2004), accessed May 5, 2025. ↩

- Jabari Asim, The N Word: Who Can Say It, Who Shouldn’t, and Why (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007); and Sherryl Kleinman, Matthew Ezzell, and Corey Frost, “Reclaiming Critical Analysis: The Social Harms of ‘Bitch,’” Sociological Analysis 3, no. 1 (2009): 47–68. ↩

- Griselda Pollock, Avant Garde Gambits, 1888–1893: Gender and the Color of Art History (Thames & Hudson, 1992); Abigail Solomon-Godeau, “Going Native: Paul Gauguin and the Invention of Primitivist Modernism,” in The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, ed. Norma Brode (Icon, 1992). ↩

- Lee Wallace, Sexual Encounters: Pacific Texts, Modern Sexualities (Cornell University Press, 2003); Stephen F. Eisenman, Gauguin’s Skirt (Thames & Hudson, 1997). ↩

- Ngahuia Te Awkotuku, “He Tangi Mo Ha’apuani,” in Paradise Camp by Yuki Kihara, ed. Natalie King, exh. cat. (Thames & Hudson, 2022), 45–47. ↩

- Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother. A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2008), and Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1–14; see also Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Duke University Press, 2016); and Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Duke University Press, 2017). ↩

- Kimberlé W. Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum 139 (1989): 139–67. ↩

- Wolfskill, “Love and Theft,” 47. ↩

- See Caroline Vercoe, “I am My Other, I am My Self: Encounters with Gauguin in Polynesia,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 13, vol. 1 (2013): 104–25; Vercoe, “Enduring Gauguin: Reflections on Gauguin’s Legacy in the Pacific,” webinar presentation, Wildenstein Plattner Institute, New York, November 2, 2023; see also Kate Keohane, “Ambivalence, Estrangement, and Opacity: Four Engagements with Landscape, Oceania, and the Legacy of Paul Gauguin,” Afterimage 49, vol. 4 (2022): 26–52. ↩

- Nina Tonga and Caroline Vercoe, “Māori and Pacific Art at the Turn of a New Millennium,” in A Companion to Contemporary Art in a Global Framework, ed. Jane Chin Davidson and Amelia Jones (Wiley, 2023), 62. ↩

- See Elizabeth Childs, “Taking Back Teha’amana: Feminist Interventions in Gauguin’s Legacy,” in Gauguin’s Challenge: New Perspectives After Postmodernism, ed. Norma Broude (Bloomsbury Academic and Professional, 2018), 229–50. ↩

- See also Kehinde Wiley, Tahiti – Kehinde Wiley, exh. cat. (Galerie Templon, 2019). ↩

- Luka Leleiga Lim-Bunnin, “‘And Every Word a Lie’: Samoan Gender-Divergent Communities, Language and Epistemic Violence,” Women’s Studies Journal 34, vols. 1/2 (2020): 77. ↩

- Vehia Wheeler and Mareikura Whakataka-Brightwell, “Ha’avarevare: Fiu with Gauguin’s Legacy and Those Who Profit From It,” Pantograph Punch, August 6, 2021. ↩

- Namsa Leuba, interview with the author, March 5, 2021. Leuba’s series Illusions was exhibited in the artist’s first solo show in the United States, Crossed Looks, at the Halsey Institute for Contemporary Art, The College of Charleston, South Carolina, August 27–December 11, 2021; see the accompanying monograph with essays by Joseph Gergel, Emmanuel Iduma, and Mary Trent, Namsa Leuba: Crossed Looks (Damiani, 2021). ↩

- Paradise Camp gained global attention when it represented New Zealand in the country’s pavilion for the 59th Venice Biennale (2022), where the installation was curated by Natalie King; see the ongoing series’s dedicated website, accessed April 30, 2025. ↩

- Kihara, quoted in Jane Ure-Smith, “Yuki Kihara: I want to reclaim our place as an indigenous, third gender community,” Financial Times, April 14, 2022. ↩

- Douglas Crimp, “The Photographic Activity of Postmodernism,” October 15 (Winter, 1980): 91–101. ↩

- Leuba, interview with the author, March 5, 2021. ↩

- Alfred Barr, Cubism and Abstract Art, exh. cat. (Museum of Modern Art, 1936). ↩

- For example, see Belinda Thomson, Christine Riding, Amy Dickson, and Tamar Garb, Gauguin: Maker of Myth, exh. cat. (Tate Modern, 2010). ↩

- Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897–98) is work number 123 in the list of 250 works students are expected to learn in AP Art History; see “SmART History: The 250 Guide to The Art of AP Art History,” in Smarthistory, January 10, 2020. ↩

- Eisenman, Gauguin’s Skirt, 42–49. ↩

- Paul Gauguin, “Letter to Georges Daniel De Monfried,” June 1901, in The Letters of Paul Gauguin to Georges Daniel de Monfreid , trans. Ruth Pielkovo (Dodd, Mead, 1922), 137. ↩

- Nancy Mowll Mathews, Paul Gauguin: An Erotic Life (Yale University Press, 2001), 243. ↩

- Solomon-Godeau, “Going Native,” 151. ↩

- Pollock, Avant Garde Gambits, 47. ↩

- See Farah Nayeri, “Is it Time Gauguin Got Cancelled?,” New York Times, November 8, 2019; see also Gauguin Portraits, exh. cat., ed. Cornelia Homburg and Christopher Riopelle (National Gallery of Canada, 2019). The Times article coincided with the exhibition’s run at the National Gallery, London, after it had debuted in Ottawa. ↩

- Amos, for example, reported admiring Gauguin’s “images of beautiful brown women” before learning about his problematic approaches to his subjects; see Wolfskill, “Love and Theft,” 47. ↩

- Eisenman, Gauguin’s Skirt, 115–16, 121–22; Suzanne M. Donahue, “Exoticism and Androgyny in Gauguin,” Aurora, The Journal of the History of Art 1 (2000): 103–21. ↩

- Andre Cavalcante, Struggling for Ordinary: Media and Transgender Belonging in Everyday Life (NYU Press, 2018), 56–64. ↩

- Timothy Wang and Sean Cahill, “Antitransgender Political Backlash Threatens Health and Access to Care,” American Journal of Public Health 108, no. 5 (2018): 609–10. ↩

- “Trump Anti-LGBTQ+ Executive Order Litigation Tracker,” The National LGBTQ+ Bar Association, April 7, 2025. ↩

- Ken Moala, “The Pacific Sexual Diversity Network: Strengthening Enabling Environments in the Pacific through Capacity Building and Regional Partnerships,” HIV Australia 12, no. 2, (July 2014): 38–40; Yoko Kanemasu and Asenati Liki, “‘Let fa’afafine like diamonds’”: Balancing Accommodation, Negotiation, and Resistance in Gender-Nonconforming Samoan’s Counter-Hegemony,” Journal of Sociology 57, no. 4 (2021): 810. ↩

- Kanemasu and Liki, “‘Let fa’afafine shine,’” 817–18. ↩

- Phylesha Brown-Acton, “Keynote Presentation,” Asia Pacific Outgames Human Rights Conference, Wellington, NZ, March, 2011. For a helpful glossary pertaining to the MVPFAFF+ initialism, see the Waipapa Taumata Rau | The University of Auckland, “Term Glossary: What Do These Terms Mean?” accessed May 4, 2025. ↩

- Eisenman, Gauguin’s Skirt; see also, Irina Stotland, “Paul Gauguin’s Self-Portraits in Polynesia: Androgyny and Ambivalence,” in Gauguin’s Challenge: New Perspectives After Postmodernism, ed. Norma Broude (Bloomsbury, 2018), 41–67. ↩

- Wallace, Sexual Encounters, 5, 2, and chapter 5. ↩

- See Francois Bauer, Raerae de Tahiti: recontre du troisième type (Haere Po, 2002). ↩

- Makiko Kuwahara, “Living as and Living with Māhū and Raerae: Geopolitics, Sex, and Gender in the Society Islands,” in Gender on the Edge: Transgender, Gay, and Other Pacific Islanders, ed. Niko Besnier and Kalissa Alexeyeff (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2014), 94–96. ↩

- Jessie Ford and Eli Coleman, “Gender diversity, gender liminality in French Polynesia,” International Journal of Transgender Health 25, no. 4 (2023): 926–42. ↩

- Deborah Elliston, “Queer History and its Discontents at Tahiti: The Contested Politics of Modernity and Sexual Subjectivity,” in Gender on the Edge, 33–35. ↩

- Leuba, interview with the author, March 5, 2021; see also Bauer, Raerae de Tahiti. ↩

- Martin Berger, Seeing Through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography (University of California Press, 2011). ↩

- Leuba, interview with the author, March 5, 2021. ↩

- Childs, Vanishing Paradise, 95. ↩

- Ibid., 98–99. ↩

- Stephen F. Eisenman, “Drag Shows, Here and There,” CounterPunch, November 25, 2022. ↩

- Jacob Bloomfeld, Drag: A British History (University of California Press, 2023), 4–5. ↩

- Judith Butler, Gender Trouble (Routledge, 1990). ↩

- bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation, “Is Paris Burning?” (South End, 1992), 145–56. ↩

- “Yuki Kihara in Conversation with Natalie King,” in Kihara, Paradise Camp, 65. ↩

- Ibid., 64. ↩

- Kerry Howe, “New Zealand’s Twentieth-Century Pacifies: Memories and Reflections,” New Zealand Journal of History 34, no. 1 (2000): 4–19. Kihara is also an appropriate representative of New Zealand due to having lived there while in boarding school and as college student. Additionally, New Zealand and Samoa have a special relationship since their Treaty of Friendship was established in 1962 upon Samoa’s gaining independence from New Zealand (which had administered Samoa from 1914 to 1962 under a United Nations mandate). ↩

- See “Samoa 2020 Human Rights Report,” US Department of State, accessed May 4, 2025. ↩

- Yuki Kihara, “Live Talanoa: Yuki Kihara and NZ Pavilion Curators,” March 23, 2022, webcast, 14:38. ↩

- n the “dusky maiden” as a recurring trope in art, see A Marata Tamaira, “From Full Dusk to Full Tusk: Reimagining the ‘Dusky Maiden’ through the Visual Arts,” Contemporary Pacific 22, no. 1 (March 2010): 1–35. ↩

- Kihara, quoted in Natalie King, “Camping Paradise: I am What I am,” Paradise Camp, 26. ↩

- Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author,” Image, Music, Text (Fontana, 1977), 142–48. ↩

- For example, in her Two Fa’afafine (after Gauguin), Kihara has substituted “Fa’afafine” for Gauguin’s “Tahitiennes” (or “Tahitian Women,” in the official English title); and in another work from the same series, Two Fa’afafine on the Beach (after Gauguin), she signals a similar substitution in reference to Gauguin’s 1891 canvas Femmes de Tahiti (Musée d’Orsay). ↩

- George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940 (Basic Books, 1994), 273–90. ↩

- Ibid., 7. ↩

- Richard Lindsay, Hollywood Biblical Epics: Camp Spectacle and Queer Style from the Silent Era to the Modern Day (Praeger, 2015), 28–32. ↩

- Camp: Queer Aesthetics and the Performing Subject: A Reader, ed. Fabio Cleto (University of Michigan Press, 1999). ↩

- Reevan Dolgoy, “The Search for Recognition and Social Movement Emergence: Towards an Understanding of the Transformation of the Fa’afafine of Samoa” (PhD diss., University of Alberta, 2000), 268, ProQuest (60453295). ↩

- Kanemasu and Liki, “‘Let fa’afafine like diamonds.’” ↩

- Eisenman, Gauguin’s Skirt, 135. I am using the name of the celebrated 1892 painting as it is cataloged by the Buffalo AKG Art Museum (formerly Albright-Knox Art Gallery), accessed May 5, 2025. ↩

- Elizabeth Childs, “Repurposing Gauguin,” in Kihara, Paradise Camp, 113. ↩

- Ibid., 114–15. ↩

- hooks, Black Looks, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators” (South End, 1992), 115–31. ↩

- Te Awkotuku, “He Tangi Mo Ha’apuani.” ↩

- C. Riley Snorton, Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity (University of Minnesota Press, 2017). ↩

- Talia Mae Bettcher, “Evil Deceivers and Make Believers: On Transphobic Violence and the Politics of Illusion,” Hypatia 22, no. 3 (2007): 43–65. ↩

- Stotland, “Paul Gauguin’s Self-Portraits,” 45; see also Eisenman, Gauguin’s Skirt, 98. ↩

- Pollock, Avant Garde Gambits, 8. ↩

- Emi Koyama, “The Transfeminist Manifesto,” in Catching a Wave: Reclaiming Feminism for the 21st Century, ed. Rory Crook Dicker and Alison Piepmeier (Northeastern University Press, 2003), 244; and Emi Koyama, “Whose Feminism is it Anyway? The Unspoken Racism of the Trans Inclusion Debate,” in The Transgender Studies Reader, ed. Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle (Routledge, 2006), 698–705. ↩

- Leuba, email correspondence with the author, November 11, 2024. ↩

- Amos had, in fact, created a self-portrait collagraph titled Mrs. Gauguin’s Shirt the same year she painted Tightrope. In the work she is seen holding up to her chest a mock T-shirt printed with the arms and breasts of the woman on the left in Gauguin’s Two Tahitian Women—as if she were presenting to the viewer her own nude upper torso. Amos included the print—issued in an edition of only five—in her important early 1994 solo exhibition Changing the Subject, at Art in General, New York—with a catalog written by bell hooks; see Emma Amos: Changing the Subject, Paintings and Prints 1992–1994, March 12–April 30, 1994, exh. cat., essay by bell hooks (Art in General, 1994), illus. p. 13. (Tightrope was not exhibited in that show.) For a readily accessible reference image, see the digital entry for the work as recently accessioned by the British Museum, London, accessed 23 May 2025. ↩