This article originally appeared in Art Journal, 84, no. 4 (Winter 2025)

Instead of asking “What is an archive?” then, in a way that leaves the archive outside and retains it as a fortress outside our world, making us its pilgrims, I shall first ask “Why an archive?” or “What do we look for in an archive?,” and only then answer what an archive is. —Ariella Azoulay, “Archive” (2017)1

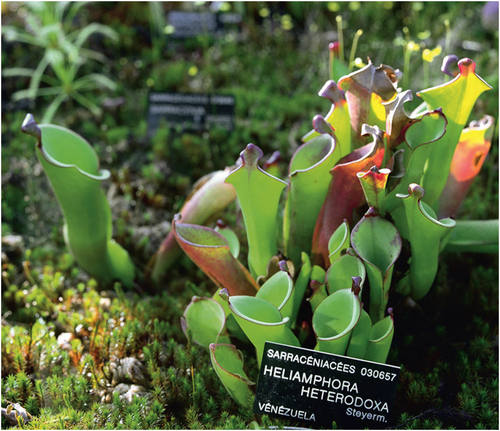

Ángela Bonadies’s (b. 1970) photographic series Las personas y las cosas (People and things; 2006–12) comprises photographs taken within archives, depicting not only the stored files and items but also the material spaces and containers that house the objects. A Venezuelan visual artist living in the diaspora since 1997, Bonadies photographed foreign and national repositories, purposefully selecting subjects that reflect the history of collecting and archiving practices. Curiously, Las personas y las cosas originated in an encounter not with an object or a person, despite the title, but with a plant: “un objeto vivo,” a living object, in the artist’s own words. While exploring a botanical garden in Lyon, Bonadies came across—and photographed—a living specimen of the Heliamphora heterodoxa, a carnivorous plant native to her homeland, Venezuela.2

This unexpected find sparked contemplation on how collections represent—or fail to represent—an idea of the “nation” from abroad. It prompted her to delve deeply into the complex process of archiving while also reframing the very notion of what an archive’s structure represents for a country. As a result, Las personas y las cosas brings together a diverse array of collections, including other botanical specimens, animal taxidermy, Indigenous ceramics, photographic records of popular culture, and many other seemingly random items. Bonadies describes her photographic encounter with diverse archives in the artist’s statement that introduces the series:

Al visitar esos archivos y colecciones me di cuenta de rasgos espaciales y de organización en común. Las cosas y su orden empezaron a regir el trabajo y creé mi propia taxonomía, anclada en las relaciones que sugería Aby Warburg entre las imágenes y sus significados y cómo se complementan. En este sentido, las clasificaciones se hicieron más teatrales.3

(When visiting those archives and collections, I noticed shared spatial and organizational features. The objects and their arrangement began to guide the work, and I created my own taxonomy, anchored in the relationships that Aby Warburg suggested between images and their meanings and how they complement each other. In this sense, the classifications became more theatrical.) Bonadies’s aesthetic proposal and her reflection on archives, evident throughout her oeuvre, are deeply rooted in her experience as a museography assistant in Venezuelan institutions, particularly at the Museo Alejandro Otero in Caracas, from 1994 to 1995. During this time, she became interested in the dynamics of archives and storage spaces, which she describes as the “backstages” where objects, seemingly dormant, generate unique narratives.4 For Bonadies, the archive is not an abstract entity; it is physical. In describing archival classifications as “theatrical,” she implies that the archive is alive, enacting a performance. Her construction of a unique, “personal taxonomy” able to challenge the people/things duality supports her paradoxical endeavor of defining and simultaneously questioning “national identity” from her diasporic perspective. In this sense, I argue that at the core of Bonadies’s exploration lies the concept of diaspora as displacement and distancing of personas and cosas. She disrupts the conventional view of archives as static, confined repositories holding singular meanings in what Bárbara Muñoz Porqué has called a “gestualidad archivística,” or archival gesturality.5 At the same time, her diasporic perspective shows the archive to be dynamic and in constant flux, mirroring the movement of people and their possessions.

Diasporic archives demand distinct interpretations, transcending conventional fixed narratives of identity. As a Venezuelan diaspora photographer based in Madrid, Bonadies delves into the complexities of preserving cultural heritage amid Venezuela’s ongoing migration crisis.6 Instead of perpetuating the archive’s conventional role of solidifying cultural identities, the artist disrupts such narratives by entering the archives and uncovering the hidden, affective essence of stored objects across national divides. In this article, I contend that Bonadies reframes “foreign” and “local” collections through a global, diasporic point of view, shedding light on Venezuela’s deteriorating national archives and their selective preservation of historical value. Ultimately, I propose that Las personas y las cosas can offer a critical perspective on the Venezuelan diaspora, reshaping archiving traditions to reflect the movements, transits, and displacements of both las personas and las cosas.7

The People of Las personas y las cosas

Michel Foucault’s well-known conception of the archive as an entity that preserves and organizes knowledge, developed in Les mots et les choses: une archéologie des sciences humaines (1966), is hinted at not only in Bonadies’s title, Las personas y las cosas, but also in the series’ photographic exploration of object arrangements within archives.8 Bonadies aims to explore the discursivity of objects—the objects’ potential to perform and to speak—and what stories they might tell the viewer. The intriguing shift from words to people casts doubt on Foucault’s idea of language as mediating our understanding of reality. In response, Bonadies, building on Foucault’s “heterotopia” as a way of rethinking relations and meanings, focuses on the visual enactment, or the “theatrical” presentation, of subjectivity and, therefore, of emotions. As Jeny Amaya and Betty Marín point out, Bonadies contests “the objectivity of the historical narrative” embedded in archiving practices—pertaining to knowledge production, fixed meanings, and transparency—by revealing the subjectivity inherent in the shaping of such official historical narratives.9 The photographer achieves this by exposing the material qualities of archived objects in a process that I call the reframing of the archival space from the positionality of diaspora.

Prior to the “archival turn,” the archive had traditionally been perceived as an abstract entity in knowledge production or depicted in quantitative terms (as data, items, classificatory lists, and the organization of objects, files, books, and more). From this outlook, lists lose their material essence, and objects cease to be recognized as physical items that power structures accumulate and organize. Expanding on already canonical theorizations of the archive—ranging from its identification as the fixed site for the modern production of knowledge to its feverish deconstruction—scholars in the archival turn have shown that this conceptualization frequently results in the exclusion of other elements and qualities within and beyond the archive itself, reducing it to a mere space or container. Bonadies’s series showcases precisely “how the process of preserving and organizing objects can amplify or hide the objects’ historical significance.”10 The archive, long considered in isolation without any acknowledgment of who created, used, or cared for it, now demands a different approach. The “abstract archive” must be replaced by a “material archive” whose materiality has the potential to unveil the power structures operating within it, enabling deciphering and contestation.11

In Bonadies’s photographic series, the nonsequential relationship between what Diana Taylor conceptualizes as “archive” (as enduring written discourse) and “repertoire” (as ephemeral embodied practice) becomes evident through the creation of a photographic performance—what Bonadies describes as “theatrical.”12 Responding to Ariella Azoulay’s questions that opened this article—“Why an archive?” or “What do we look for in an archive?”—and building on Taylor’s work, I aim to focus on what archives can do and what artists—in this case, Bonadies—do with archives. Javier Guerrero’s scholarship has significantly influenced the material doing of photographic archives, emphasizing their haptic (or tactile) nature and inviting us to “tocar el archivo como piel, tocar la piel de archivo como activador de la plasticidad del cuerpo, activando a su vez las íntimas relaciones entre cultura visual, cultura material, cuerpo y archivo.”13 Studying archives within their sociopolitical contexts and considering their material circulation, as well as the significance of their material production and reproduction, encourages us to view archives as more than mere collections, lists, or containers of objects. Bonadies actively puts these theoretical formulations into practice in Las personas y las cosas.14

The series itself constructs a vast archive. By building a collection of photographs of archives, Bonadies encourages us to perceive the archive as a material entity but also to understand it as a method of photographic practice. Bonadies relates the inner workings of archives to those of a photographic camera: a contained space that captures external realities, transforming them into something else—preserving, enclosing, and imbuing them with new meanings.15 Ann Laura Stoler has emphasized that the “pulse of the archive” is discernible only when we focus on the archive as a “process,” recognizing its dynamic life and malleability. That pulse lies in the “quiescence and quickened pace of its own production, in the steady and feverish rhythms of repeated incantations, formulas, and frames.”16 In photographically reframing archives, Bonadies is not only deciphering their internal structures and generative forces—and creating new ones—but also exploring the archives’ potential for their meanings to change.

Las personas y las cosas, as a conceptual art project, includes thematic sections, each with a varying number of color photographs, which I analyze below. These sections are titled Ángulo Central; Cables y Conexiones; Paisajes Enmarcados; Iconografía Nacional; Cosas que hablan; and Custodios y Testigos (Central Angle; Cables and Connections; Framed Landscapes; National Iconography; Things that speak; Custodians and Witnesses) and others not covered here. The first exhibition, held at Periférico Caracas/Arte Contemporáneo (Caracas, Venezuela, 2009), featured approximately 130 photographs, some mounted and others displayed in vitrines, in various sizes.17 The two-word section titles allude to Linnaean taxonomy, a binomial system of biological nomenclature, which Bonadies cites in artist’s statement. Created by the “father of taxonomy,” Carl Linnaeus, in his work Systema Naturae (1735), this system was widely used for species identification well into the nineteenth century and aimed to classify living beings into kingdoms—animal, vegetal, and mineral. It then organized species into classes and orders, creating a hierarchical model that simultaneously included and excluded.

The photographs respond to the types of arbitrary preservation processes and organizing principles intrinsic to hegemonic and official archives. In the artist’s statement on the series, Bonadies raises the uncomfortable question of how these processes actually obscure the historical value of objects stored in archives that are connected to an “idea romántica de pertenencia y al inicio de la forma contemporánea de coleccionar.”18 The allusion to Linnaeus and the choice of photography as a medium are intriguing decisions. On the one hand, rather than establishing a hierarchy, Bonadies employs a deliberately ambiguous and disjointed structure throughout the series. She enters various archives, each with its internal classification system, captures these spaces and objects—disrupting their order—and creates a personal organizational apparatus for her image-archive. The series’ division into sections challenges restrictive classifications, revealed only through her own organizing principles, while questioning Linnaeus’s classificatory system. On the other hand, Bonadies also critiques photography as a supposedly faithful tool for archiving and taxonomy creation since the early twentieth century, particularly within colonial botany, the natural sciences, and cultural anthropology. By blurring hierarchies among specimens, objects, and spaces, she challenges archiving norms across disciplines that have relied heavily on visual methods. Her aim is to encourage reflection on how exclusionary systems dominate official historical archives, offering a counter-archive aligned with contemporary theoretical perspectives.

The diverse Venezuela-based archives featured in Las personas y las cosas include photographic repositories, ornithological collections, private botanical and entomological collections, art collections, blood banks, and many other type of archives.19 Bonadies deliberately withholds information about the specific sites from which the images originate by omitting contextual details and captions, allowing the objects to tell their stories independently of their location.20 In the words of Muñoz Porqué, “[Bonadies] desterritorializa el origen de los documentos para hacerlos ingresar en un nuevo montaje narrativo.”21 By making the archival spaces untraceable in terms of both visibility and concealment, she creates an interplay between fiction and reality within the series’ internal structure.

Bonadies chose archives based not on their historical significance or the value of their contents but on her own perception of shared spatial and temporal organizational traits within these archives—traits she simultaneously aims to challenge by photographically dissecting their internal logics. By bringing together different archives, each with its disconnected temporalities and geographies, Bonadies allows for diverse interpretations based on the “folding and unfolding” of history as seen in the photographed objects, outside any linear chronology or official history, “effectively breaking its linear nature and presenting what she describes instead as ‘smaller, different histories, or [those] of everyday life.’”22 Las personas y las cosas juxtaposes seemingly disconnected elements to create a complex network among the elements found within the archives.

As identified by Hal Foster, an “archival impulse” in contemporary art practices—particularly contemporary art photography—has prompted artists to create artifacts that link seemingly unrelated archival objects and spaces by re-contextualizing them, fostering “affective association[s]” rather than objective systems.23 Bonadies’s effort to reframe archives aligns with this contemporary impulse to “connect what cannot [at first] be connected.”24 In the artist’s statement, she notes that intentionally stripping the archived objects and spaces of context is inspired by the image-relationship system of Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas (1924–29). This “atlas” entailed the “decontextualization” of thousands of images from the (Western) history of visuality. Warburg arranged and rearranged these images based on an operation defined by Georges Didi-Huberman as “montage,”25 to reflect on the movement, circulation, and transformation of visual icons.26 Along with Warburg, Bonadies questions the logic that, on the one hand, regards chronology in art history as an unquestionable category and, on the other, determines which objects enter—or do not enter—official history.27

Lisa Blackmore has referred to Bonadies as an “archon caprichosa”—challenging Derrida’s “archon,” who effects a “lúdica y oximorónica” (playful and oxymoronic) reinterpretation of the grandiose role of the archon as the authority within archives.28 This series points to a separation between archival content and the individuals traditionally associated with archives: archivists and users. Bonadies prompts us to consider: Who are the personas behind these cosas? While most of the images in the series depict objects and spaces, personas only appear in Custodios y Testigos. This section comprises more than fifteen untitled, full-body portraits featuring not only the owners of personal archives (such as an athlete’s trophy collection or an art collector’s valuables) but also individuals crucial to the survival of historical archives. We often focus on the “intellectuals” who author studies deciphering hidden meanings pulled from the depths of files. In contrast, Bonadies aims to portray those who keep the archive’s content alive, such as custodians, laboratory technicians, cleaners, and assistants, whose work remains largely invisible. She aims to remove the aura that theory has bestowed upon the archive, thereby obscuring the material potential of objects and the individuals responsible for caring for this materiality. Bonadies makes visible their often-unseen labor, including affective labor. The portraits of these custodios and testigos—agents of the archive—posing among shelves and cabinets contribute to the “performativity” of the archive’s material.

The Things of Las personas y las cosas

As quoted above, Bonadies underscores that the reframing of the archive produced “theatrical” classifications, determining the “order” of the things she captured. In her own words, theatrical here means a “puesta en escena que no es tal, pero parece, que nos susurra ficciones a través de la fotografía . . . [es] una forma de mostrar que genera otros relatos.”29 In forging connections among objects based solely on the “meanings” she visually attributes to them, Bonadies develops her own counterarchival process of classification as a performance. The internal structure of Las personas y las cosas “interweaves a narrative that emphasizes the humanization of the archival space and its domestication.”30 Central to this is the anthropomorphism of archived objects, where the photographic camera and the lenses’ reframing imbue objects with a sense of “aliveness.” Paradoxically, while preservation might imply the cessation of objects’ functions in the real world, by decontextualizing and opening the meaning of objects, Bonadies portrays them in a way that allows them to continue to exhibit agency and vitality.

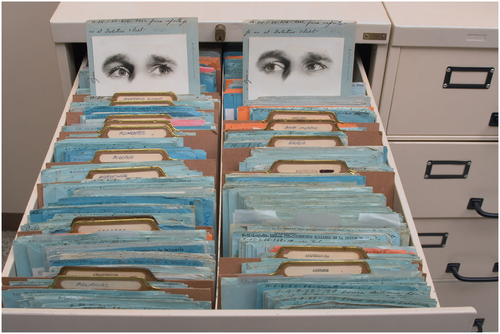

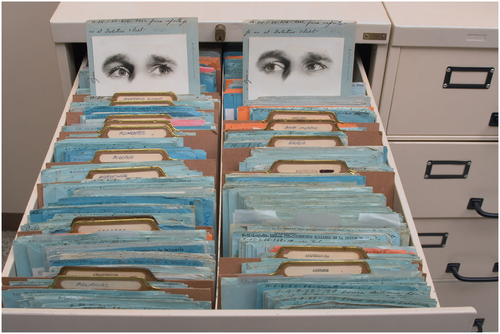

Ángela Bonadies, Cosas que ven y hablan, photographed at the Archivo Fotográfico Revista Shell, Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, Caracas, from the series Cosas que hablan: Las personas y las cosas, 2006–12 (artwork © and provided by Ángela Bonadies)

Ángela Bonadies, Bocas, Arroz, Arte Murano, photographed at the Archivo Fotográfico Revista Shell, Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, Caracas, from the series Cosas que hablan: Las personas y las cosas, 2006–12 (artwork © and provided by Ángela Bonadies)

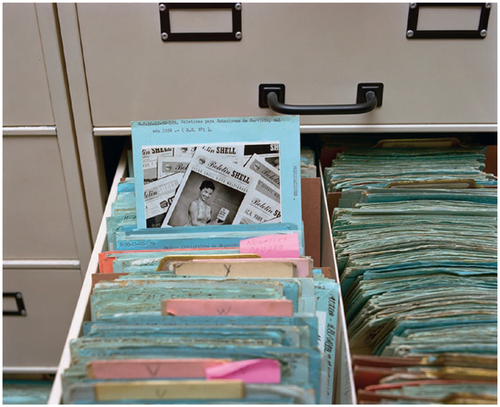

This is particularly evident in Cosas que hablan, where Bonadies complicates the notion of the archive as container by directing the viewers’ gaze to the actual physical containers (cabinets, shelves, etc.) that hold objects. In the photograph titled “Bocas, Arroz, Arte Murano,” a close-up frame reveals a photograph emerging from an open file-cabinet drawer. The shot is focused and narrow, displaying only the open drawer with partly visible folders. The rephotographed image is a portrait, featuring only the nose and mouth in an exaggeratedly wide-open expression, with hands pulling the mouth open. We see that this portrait has been classified under “bocas” in the cabinet. Two additional folder labels are visible—“Arte Murano” and “arroz”—although no photos can be seen. Bonadies not only seeks to emphasize the arbitrariness of these categories (mouths, rice, Murano art), whose only connection is their alphabetical order, but also intends to highlight such incoherence by creating a new arrangement or “staging” of the rephotographed content. Similarly, the photograph “Cosas que ven y hablan,” in the same section and taken from the same archive, displays another file cabinet and is a clear example of this performative rearrangement of archival content: Two photos or realistic drawings peeking out from their folders showcase two pairs of eyes that appear to look around, perhaps searching for each other.

The mouth and eyes reframed within Bonadies’s photographs “see” us and “speak” to us. Thus, the archives’ contents can observe and communicate on their own, without the intellectual mediation of a scholar. What stories do they wish to convey? The significance of what the archive holds remains concealed until the images are removed from their drawers, until they are touched and engaged with, until they are rephotographed by Bonadies. Both “Bocas, Arroz, Arte Murano” and “Cosas que ven y hablan” propose a haptic engagement with the contents of the archive: this suggests understanding archives as intended not just for study but also for a more sensory—auditory, visual, and tactile—experience of the materials.

Bonadies’s aforementioned reference to Linnaeus’s classification of the natural and animal world suggests that the objects within her “theater-archive” form a living, multispecies ecosystem and draws attention to the intertwined presence of plants and animals.31 Four images stand out in Cosas que hablan, emphasizing the paradoxical coexistence of life and stillness within archival material. The photograph titled “Gato doméstico” depicts a somewhat untidy room with archival closets and shelves containing unidentified sealed jars. In the center, a table displays disorganized taxidermy specimens, and in the foreground, a taxidermied deer has its back to us. This dead animal acting as if it were alive is a prime example of the previously mentioned theatrical performance within the archive. By reframing an archival specimen that appears alive but is not, Bonadies creates tension within the photographic representation of that particular archive’s room, thereby disrupting its status as an archive.32

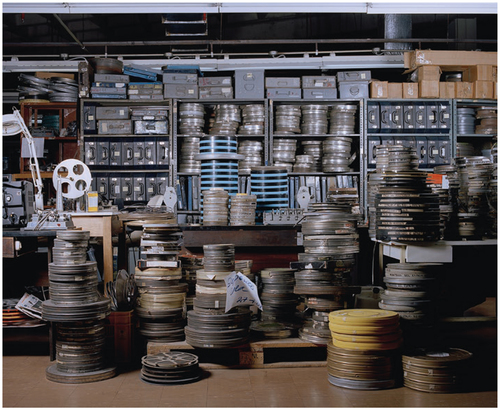

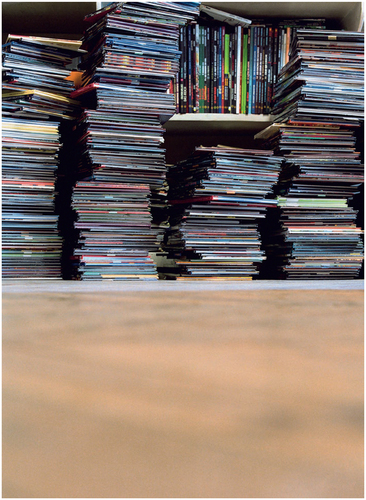

Moving from animals to things, the three photographs in the “Cosas que crecen” triptych—I, II, and III—depict a pile of cacti, a pile of film reels, and a pile of thin hardcover books. There are no indications of whom these piles belong to, although the room in the second photo suggests a “cinemateca.” However, what is intriguing about this set of three images, titled “things that grow,” is how it frames the archival accumulation of objects, emphasizing the idea of active quasi-natural growth rather than static accumulation. The first image, featuring cacti, conveys the vitality of real plants growing vertically; alongside them, the film reels and books also appear to grow in vertical piles. Both “Gato doméstico” and “Cosas que crecen” illustrate the coexistence of living and nonliving things, blurring the boundaries between them. The taxidermied animals that appear to roam free and the continually growing piles suggest the archive has the potential to overflow its space.

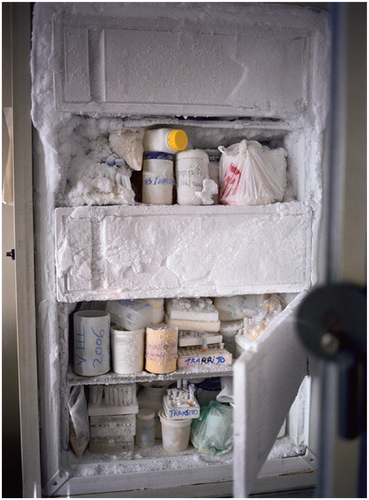

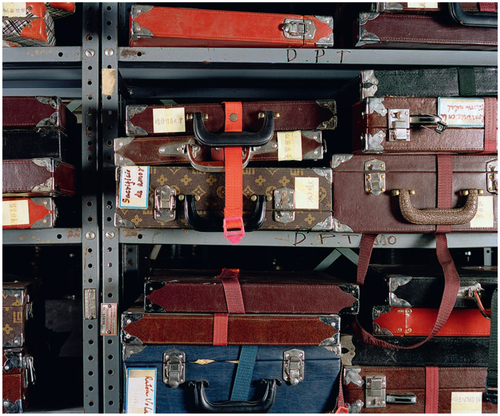

The last two photographs in Cosas que hablan, titled “Tránsito” and “Sacrificio de amor,” deepen Bonadies’s exploration of aliveness within the archive. In “Tránsito,” an open refrigerator showcases biological samples, some tagged with the term “transit,” sparking reflection on the unknown destination of the test tubes. The display of biological samples complicates the idea of archives as stagnant spaces, injecting life—albeit dormant life—into the archive. Similarly, in any archive, everything is, in Bonadies’s words, “un poco dormido hasta que lo sacamos o lo tocamos, lo vemos.”33 On the other hand, “Sacrificio de amor” showcases a shelf filled with stacked suitcases—another example of a “live” pile—one of them marked with the handwritten phrase “love sacrifice,” inviting speculation. These two photographs, along with their titles, not only reflect the openness of the archive to interaction but also illustrate the possibility of movement and displacement of archival objects as they circulate globally, tying into her overall practice as diasporic. Bonadies emphasizes that the archive has the potential to be “activated” at any moment and from any location.34

Ángela Bonadies, Cosas que crecen II, photographed at the Archivo Fílmico de la Cinemateca Nacional de Venezuela, Biblioteca Nacional, Caracas, from the series Cosas que hablan: Las personas y las cosas, 2006–12 (artwork © and provided by Ángela Bonadies)

Ángela Bonadies, Cosas que crecen III, photographed at a bookstore in Lyon, France, from the series Cosas que hablan: Las personas y las cosas, 2006–12 (artwork © and provided by Ángela Bonadies)

The camera captures an ever-evolving narrative within seemingly static repositories. Bonadies emphasizes that “depend[iendo] del orden en que se realice una apertura, puede haber distintas lecturas e historias.”35 on the order in which an opening is made, different readings and stories may emerge.” Bonadies, in discussion with the author, October 27, 2020.] Rather than offering a single reading of Las personas y las cosas, the photographer’s interest lies primarily in reconfiguring the archive chiefly as a space to account for the possibilities that arise when extracting, touching, seeing, hearing, and thus feeling the objects that inhabit its cabinets, drawers, and shelves.

Ángela Bonadies, Tránsito, photographed at the Banco Municipal de Sangre, San José, Cotiza, Caracas, from the series Cosas que hablan: Las personas y las cosas, 2006–12 (artwork © and provided by Ángela Bonadies)

Ángela Bonadies, Sacrificio de amor, photographed at the Archivo Fílmico de la Cinemateca Nacional de Venezuela, Biblioteca Nacional, Caracas, from the series Cosas que hablan: Las personas y las cosas, 2006–12 (artwork © and provided by Ángela Bonadies)

Reframing Archives from the Diaspora

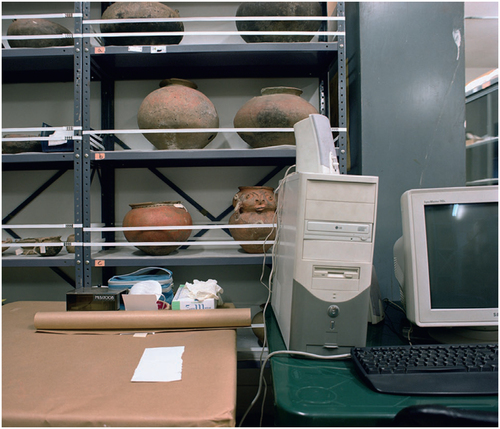

Three sections of Las personas y las cosas delve into the notion of space: Ángulo Central, Cables y Conexiones, and Paisajes Enmarcados. In Paisajes Enmarcados, the point of view from inside the archive highlights the external space, primarily through windows functioning as frames, revealing glimpses of the city Bonadies left behind. However, these “frames” also create a sense of being imprisoned within the archive. Cables y Conexiones focuses on contained spaces inside the archive, highlighting its failure to effectively preserve and organize its contents: We see disorderly rooms with random objects scattered on the floor, including a trunk and a human mannequin, desks cluttered with papers, and shelves holding items such as Indigenous ceramics and human skulls. Ángulo Central further explores these aspects, featuring dimly lit hallways lined with shelves, files, racks, and boxes, and every image showcases centrally framed hallways where the “central angle” creates a vanishing point that imparts a sense of infinity. In these photographs, we see the archive as a deep, dark space and are led to contemplate what is concealed behind cabinet doors, at the backs of shelves, and inside cabinet drawers. The use of perspective leads viewers to reconsider elements such as chronology, value, and the ordering logic imposed upon archived objects.

Ángela Bonadies, Untitled, photographed at the Museo de Ciencias Naturales, Centro Adolfo Ernst, Roca Tarpeya, Caracas, from the series Cables y Conexiones: Las personas y las cosas, 2006–12 (artwork © and provided by Ángela Bonadies)

Ángela Bonadies, Untitled, photographed at the Museo de Ciencias Naturales, Centro Adolfo Ernst, Roca Tarpeya, Caracas, from the series Cables y Conexiones: Las personas y las cosas, 2006–12 (artwork © and provided by Ángela Bonadies)

Ángela Bonadies, Untitled, photographed at the Museo de Ciencias Naturales, Centro Adolfo Ernst, Roca Tarpeya, Caracas, from from the series Ángulo Central: Las personas y las cosas, 2006–2012 (artwork © and provided by Ángela Bonadies)

Ángela Bonadies, Untitled, photographed at the Archivo Fílmico de la Cinemateca Nacional de Venezuela, Biblioteca Nacional, Caracas, from the series Ángulo Central: Las personas y las cosas, 2006–12 (artwork © and provided by Ángela Bonadies)

Revealing the internal spaces of rooms and containers in this way presents a paradox. While these archives aim to preserve cultural value or history, the images depict the abandonment, precariousness, and active decay of these spaces, oscillating between showing “el estado ‘natural’ de los acervos y en descubrir . . . el absurdo de su permanencia sin destinación ni funcionalidad.”36 By revealing these spaces in a raw manner, Bonadies highlights the inaccessibility of archives in Venezuela, shaped by a political and economic situation that reflects a larger cultural crisis. This theme is one that Bonadies has explored in works such as Estructuras de excepción (2011–13) and La Torre de David (2010–22), both of which address the literal consequences of crisis through the decay of urban spaces, reimagined as archives left in ruins. The spaces in her photographs—whether urban or archival—signify abandonment and collapse but at the same time preserve the material traces of the state’s failure and embody what Bonadies presents as a constant state of exception, a condition that is equally translatable to the state of the actual nation she photographs.37

As Blackmore has pointed out, “many archives, museums, and collections ran [sic] by the Venezuelan state suffer under policies of non-acquisition of new content and a dearth of available funds.”38 However, beyond that, Bonadies wants to expose the fact that state powers will not allow nonhegemonic readings of the archive, “fuera del elogio heroico de la construcción mitológica de la nación.”39 By stripping archival objects of their original locations and context, Bonadies prompts reflection on archives as spaces of ongoing presence-absence and continuous diasporic displacement. Her method of engaging with archives through photography aligns with an artistic practice—as described by photo historian Sarah Bassnett—that, while not overtly political, delves into themes of memory and identity, carrying profound political implications.40 When photography critically interacts with an archive, it always explores issues that extend beyond the intimate and personal, addressing the concerns of a broader community within a specific sociopolitical context.41

Many contemporary Venezuelan artists in the diaspora have explored the relationship between national identity and state power within the context of Venezuela’s ongoing crisis. This includes the performance artists Deborah Castillo, with works such as Emancipatory Kiss (2013) and Demagogue (2015), and Érika Ordosgoitti with Intervención monumental (2012); photographers such as Alexander Apóstol with his Residente pulido (2001), Skeleton Coast (2005) and Ensayando la postura nacional (2010), and Luis Molina Pantin with Arqueología urbana del Centro Simón Bolívar (2004–05); and multidisciplinary artists like Pepe López with his installation Crisálida (2017), among many others.42 Like Bonadies, these artists engage with the material and symbolic remains of the state, examining how power and memory intersect in Venezuela’s prolonged state of decay.43 Bonadies’s work adds to these proposals by focusing on archives and objects as silent witnesses to the fragmentation of national identity. I would like to conclude this article by reflecting on how Las personas y las cosas explores the interconnection of space, identity, nation, and diaspora.

In describing her encounter with the Heliamphora heterodoxa, Bonadies notes that she found in the etymology of the carnivorous plant’s name (helo, “sun,” or helio, “swamp”; amphora, “container”; heterodoxa, “rare” or “dissident,” in her words) a possible definition of her “country,” Venezuela: “Esa clasificación me sugirió la posibilidad de hacer una descripción de país desde ‘las cosas’ que guarda y custodia, que clasifica y valora.44 There is a suggestive contrast between “Heliamphora Heterodoxa” (depicting a living specimen in the botanical garden in Lyon) and the photograph that follows it, “Heliamphora Heterodoxa II” (depicting a plastic one). The artificial rose with some green foliage is placed on a shelf in what appears to be a room within another unknown archive. Bonadies’s choice to title the photograph “Heliamphora Heterodoxa II” is laden with irony, emphasizing the unconventional nature of this representation and playing with the viewer’s expectations. While the encounter in Lyon with an original specimen suggested to Bonadies a definition of Venezuela, one might speculate that the second encounter, with the plastic plant, also alludes to Venezuela. This material tension, another example of the interplay between fiction and reality, prompts us to reflect on the deteriorating condition of archives in Venezuela and the migratory crisis the country has confronted over the past decade.45 This pair of plants opens the series as a powerful gesture to account for what remains local and what is preserved globally or “from abroad.” It also portrays the internal and external dynamics of a Venezuela in a constant state of crisis. In looking at Bonadies’s work, reflecting on the archive is to reflect on the idea of “nation” from a distance, from a diasporic perspective.

The so-called Revolución Bolivariana, launched by former president Hugo Chávez after his election in 1998, marked a shift toward socialism and anti-imperialist rhetoric in Venezuela. Chávez’s presidency (1999–2013) introduced sweeping political, social, and economic reforms, many of which polarized the country. Following Chávez’s death in 2013, Nicolás Maduro assumed power and continued these policies. The pace of emigration accelerated dramatically in 2014 as state violence, hyperinflation, food and medicine shortages, and political repression intensified under Maduro’s government, exacerbating an already unfolding crisis that had begun in the early 2000s with previous waves of middle- and upper-class emigration.46 Las personas y las cosas, initially conceptualized in 2006, unfolded after Bonadies had spent ten years in the diaspora, specifically in Madrid, and temporarily returned to Venezuela in 2007. Returning to her homeland, she aimed to rekindle a primarily emotional relationship with the space, reflecting on the experiences faced by any diasporic subject regarding the tension between “origin” and “identity” through the preserved historical memory or lack of history of the country. This reflection, for Bonadies, transcends the limitations imposed by the crisis, such as the insecurity and fear that prompted her to migrate in 1997.47

Bonadies considers a metaphor of the country left behind as a “closed” archive, preserving values, objects, and even complex emotions of belonging, making her artistic engagement with archives not only meta-reflexive but also affective. Particularly within the series’ context—the Venezuelan migratory crisis—the photographs function as an “archive of feelings” as defined by Ann Cvetkovich.48 The series’ sections reflect on what remains when individuals have no choice but to leave their homeland behind; as Bonadies notes, “se deja el territorio, pero no se abandona.”49 The “affective power of archives” is apparent in Las personas y las cosas as the series contemplates how photographs, when linked to the materiality of archives, necessitate alternative, experimental approaches to archiving.50 This has led Bonadies to create a new type of archive, one that is not completely left behind and instead is experienced, is felt, through the tactile qualities of the photographic image, acknowledging that what we feel—both emotionally and materially—is often unclassifiable.51

Venezuela’s stagnation and social, political, and economic situation have led Bonadies, like many others, to settle in the diaspora and consequently bear witness from a distance to a country that, akin to the state of the national archives, has worsened considerably over the years. Regarding this, in the catalog text of Las personas y las cosas, Blackmore explains that:

En la gestión patrimonial de la Venezuela del llamado Socialismo del Siglo XXI el archivo es un espacio contestado, un territorio que es termómetro de la polarización política y los objetos se resucitan y vuelven a tener utilidad en actos performativos enunciados desde el poder, según una lógica historiográfica-patrimonial, como lo plantearía Michel De Certeau, que vuelve al espacio del pasado a través de objetos o personajes para entrelazar el ahora con el entonces.”52

(In the management of Venezuela’s heritage under the so-called Socialism of the Twenty-first Century, the archive is a contested space—a territory that serves as a thermometer of political polarization. Objects are resurrected and regain utility through performative acts articulated from positions of power, according to a historiographic-heritage logic, as Michel de Certeau might argue, which returns to the space of the past through objects or figures in order to intertwine the now with the then.)

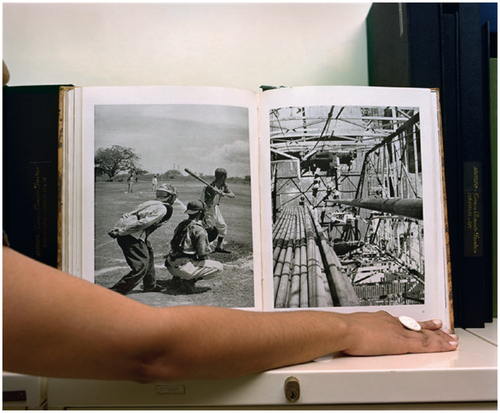

Iconografía Nacional reflects on these issues through four images. The first features an Indigenous ceramic figure displayed on cardboard against a backdrop of filing boxes; the second showcases a photobook opened by an anonymous arm, revealing a photograph of baseball players on the left and a metal industrial structure on the right. The last two images originate from the same filing cabinet photographed in Cosas que hablan. When opened, the folders reveal two black-and-white images rephotographed by Bonadies: One displays a snapshot of Boletín Shell from 1958, and the second depicts a lady playing Ping-Pong or table tennis with the handwritten label “Deportes (Ping-Pong).”

Ángela Bonadies, Untitled, photographed at the Archivo Fotográfico Revista Shell, Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, Caracas, from the series Iconografía Nacional: Las personas y las cosas, 2006–12 (artwork © and provided by Ángela Bonadies)

Ángela Bonadies, Untitled, photographed at the Archivo Fotográfico Revista Shell, Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, Caracas, from the series Iconografía Nacional: Las personas y las cosas, 2006–12 (artwork © and provided by Ángela Bonadies)

In a country where modern history is often measured by the symbols imposed by the government—such as Simón Bolívar, the tricolor flag, and a handful of patriotic heroes—Bonadies disrupts the conventional archival narrative with her exploration of a different “national iconography” and the exclusion of often arbitrary “officialized” symbolism. By withholding identificatory information, Bonadies aims to move beyond any didacticism and to decenter the “utilidad ideológica,” or ideological utility, of the archive, as employed in the current Venezuelan context.53 The absence of Bolívar and the flag in her “national iconography” prompts reflection on the political significance of what is preserved and displayed, in contrast to what is purposely hidden from the public. With this, Bonadies calls attention to the history of Venezuela, the sustained polarization, and the lack of historical-cultural memory.54 Iconografía Nacional allows us to reconsider how a government selects its ideological icons, relegating other historical objects to the darkness of the archive. In Bonadies’s “national iconography,” Indigenous and popular history take precedence in responding to a government that has disregarded many unseen stories in favor of single-hero narratives. According to Bonadies, the tension produced by this state of affairs resides in the unspoken: “el hecho de estar frente a un espacio que dice algo, pero sobre todo deja de decir muchas cosas.”55 This section of Las personas y las cosas, then, reveals a subtle reflection on the univocal, totalitarian truth imposed by state powers in contemporary Venezuela. Bonadies constructs a visual discourse outside the dictated narrative—a counter-archive—moving beyond the mythological construction of the nation. The four photos of unidentified items, along with the section’s ironic title, underscore that a definition of the “nation” is not fixed and certainly not determined by what an “official” archive chooses to preserve.

Iconografía Nacional and the photographs from Cosas que hablan that display open file cabinets actually depict the archive of Revista Shell. Although I have argued that specific locations are not pertinent to Bonadies’s series, this archive is worth locating in relation to the issues discussed above. Sponsored by the Royal Dutch Shell oil company, Revista Shell began to be published quarterly in Venezuela in 1952 and established itself as a key referent in the dissemination of Venezuelan culture until it ceased publication in 1962 due to budget cuts. The magazine’s photographic archive, donated to the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello in Caracas, comprises over fifteen thousand photographs reflecting the vibrant social life and the modern architectural development of Venezuela in the 1950s and 1960s, following the first oil boom of the 1920s.56

The Shell archive, in disseminating a “visión alegre y progresista, a pesar de la coexistencia con la dictadura militar,” insisted on normalizing “un código fotográfico que en su expresión documental quisiera ser huella y, en el caso de los años 50 en Venezuela, certificado de presencia de la modernidad.”57 Shell represents both the aspirations and contradictions of Venezuelan modernity. By capturing archives in their current state of disrepair, Bonadies reveals a broader historical continuum of deterioration—from the formation of the independent nation in the nineteenth century to the oil boom and the current failed state. In other words, the series not only documents present-day fragility but also reflects a broader cultural, political, and economic decline that appears as constant. The “literalidad,” or literal quality, and binaries-based organization of the Shell archive, with categories such as “espacio rural y espacio urbano,” “Europa y América,” “hombres y mujeres,” and “primer mundo y tercer mundo,” intrigued Bonadies, and, in turn, she aimed to highlight its incoherence, its arbitrary organizational nature, with the photographs.58 The reappearance of this archive within Bonadies’s series indeed speaks to a past of imagined wealth and industrial development in stark contrast to the precarity of the archives where such photographs are supposedly preserved. The photography in the Shell archive, as stated by Blackmore, played a role in shaping and validating a sense of national identity, although that identity has always remained precarious and easily unsettled. Bonadies, in rephotographing that same archive, produces a countervisuality: an archive that actively engages with and responds to the official visual narratives established by the Venezuelan state by claiming a right to respond through her photographic gaze.59

Archival Affects

Ángela Bonadies’s interest in objects, images, and their relationships with subjects clearly suggests that a visit to an archive always entails a physical, personal, and emotional interaction with the items stored there. She asserts that “la relación afectiva con el archivo convierte toda lectura en un contra-archivo o en una anulación de la lectura única.”60 This highlights archival affectivity (as experience) over archival effectiveness (as official value). The photographer advocates for the stories that have been rendered invisible by official narratives since the state’s formation, and particularly in its recent history. In Las personas y las cosas, there exists an open discursive space, humanized and possibly healing, addressing the nation’s sociopolitical situation, the migratory crisis, and the cultural objects it has made invisible, and transcending the narratives imposed during the processes of selection, conservation, classification, and archiving official “iconographies.” In her earlier series Inventarios (2002–14), Bonadies reflected on immigrants and the objects they carried from one country to another, challenging preconceptions of belonging and assimilation.61 Today, by focusing instead on what is left behind—fifteen years after creating Las personas y las cosas—Bonadies thinks on the possibility of returning, like many of us in the diaspora, to observe how the archives, along with the spaces and objects in her photographs, have transformed, evolved, further decayed, or even disappeared.62

A diasporic subject’s bond to the memory of the place that has been left behind, treated as an archive, encapsulates the challenges of displacement—whether willingly or by force. This attachment reveals how the migrating individual grapples with their affective ties to the memories associated with that place—memories that are, at once, carefully safeguarded in a metaphorical archive and scattered across what they bring with them and what remains. The archive transforms into a space where both people and things gather upon leaving one’s homeland, finding new forms of belonging in the aftermath of migration.

I would like to thank the artist, Ángela Bonadies, for her generosity in sharing her photographs and the context of her work with me; any mistakes are my own. I also extend my gratitude to Víctor Sierra Matute, Irina R. Troconis, and my editor, Tess C. Rankin, for their support in reading and editing earlier versions of this article. Thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful reading and insightful recommendations to improve this piece.

Cristina E. Pardo Porto is a scholar of Latinx and Latin American art and visual culture with a focus on Latin America and the Caribbean. She is an assistant professor at Syracuse University. Her current book project offers a decolonial history of photography from the perspective of diaspora. Her recent curatorial work includes Joiri Minaya: Unseeing the Tropics at the Museum (Syracuse University Art Museum). [330 HB Crouse Hall, 111 Crouse Dr, Syracuse, NY 13210,] cepardop@syr.edu

- Ariella Azoulay, “Archive,” in Political Concepts: A Critical Lexicon, published July 21, 2017. ↩

- Unless otherwise indicated, translations are mine. All photographs reproduced in this article are courtesy of the artist, © Ángela Bonadies. Bonadies’s section titles are italicized, and individual photograph titles are in quotation marks, preserving her irregular capitalization. Bonadies’s work has been featured nationally and internationally in exhibitions such as El privilegio de la imagen (Academia de España en Roma, 2022), The Matter of Photography in the Americas (Stanford University, 2018), A Universal History of Infamy (LACMA, Los Angeles 2017–18), La Bestia y el Soberano (MACBA Barcelona and WKV Stuttgart, 2016), among others. She has received prestigious awards, including the MAEC-AECID Fellowship at the Real Academia de España en Roma (2018) and the Residency Award at 18th Street Arts Center, granted by LACMA (2016). ↩

- This text is part of a larger artist’s statement on the series used as a press release and in talks and lectures, shared with the author in 2020. ↩

- There, Bonadies collaborated with figures who helped shape her interdisciplinary approach, including Tahía Rivero; curators Jesús Fuenmayor, Gabriela Rangel, and Miguel Miguel; photographer Vasco Szinetar; poet Yolanda Pantin; editor María Fernanda Paz Castillo; writer Juan Carlos Chirinos; and architects Ekaterina Afanasiev and Francisco Mujica, among others. She also participated in the organization of exhibitions, contributing to projects with curator Ruth Auerbach. Bonadies’s experience during those years was further enriched by studying under photographer Ricardo Armas and through her interactions with curator José Luis Blondet at the Museo de Bellas Artes. Bonadies, in discussion with the author, January 3, 2025. ↩

- Bárbara Muñoz Porqué, “Del objeto a la colección: la imagen del archivo en Ángela Bonadies,” Tráfico Visual, January 28, 2020, last accessed June 12, 2025. ↩

- Bonadies first left Venezuela in 1997, living in Spain (Barcelona and Donostia/San Sebastián) until 2007 before returning to Caracas, where she stayed until 2018. She then settled in Madrid. Over two decades, she also worked in artistic residencies in California, Salvador de Bahía, and Rome. Bonadies in discussion with the author, October 27, 2020. ↩

- Las personas y las cosas is the work that, in Bonadies’s words, most literally engages with archives and archiving. Bonadies, in discussion with the author, January 3, 2025. However, she has reflected on archives and repositories across her practice, as evident in works such as Inventarios (2002–14) (see Luis Miguel Isava, “Los artefactos de Ángela Bonadies: Inven(ari)ar la ironía de las cosas,” El Estilete, July 7, 2015); and Palacio Negro (2011–12; see Mya Dosch, “Temporalities of Progress and Protest: Renovation and Artist Interventions at the Mexican National Archive,” Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism 15, no. 1: 1–15); La Torre de David (2010–22), created with Juan José Olavarría; and in her ongoing work, La mujer invisible (o invencible), which draws from familial and audiovisual archives of Venezuelan television. These series examine the intersection of memory, documents, and structures, reflecting Bonadies’s overall focus on how archives mediate history and identity. Las personas y las cosas, my sole focus in this essay, deepens these themes by shifting toward a more personal view of the relationships between people and repositories. ↩

- Lisa Blackmore suggests that Bonadies’s reference to Foucault is a subtle nod, using the word “thing” to forgo specific narratives in favor of documenting the everyday reality, revealing “how an archive actually is.” Blackmore, “Ángela Bonadies: Periférico Caracas/Arte Contemporáneo,” ArtNexus 76 (March–May 2010). Similarly, Jeny Amaya and Betty Marín highlight Bonadies’s emphasis on documenting the “everyday” in archives. Amaya and Marín, “What Can Archives Reveal? A Fascinating Look Inside Mexican Prison Records and Scientific Files,” KCET Public Media Group of Southern California, October 6, 2016. Bonadies also engages with Foucault’s concept of the “panopticon” in Palacio negro (2011–12), centered on the former prison Palacio de Lecumberri in Mexico City. ↩

- Amaya and Marín, “What Can Archives.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Azoulay, “Archive.” ↩

- Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas (Duke University Press, 2003), 16. ↩

- “To touch the archive like skin, to touch the skin of the archive as an activator of the body’s plasticity, thereby activating the intimate relationships between visual culture, material culture, the body, and the archive.” Javier Guerrero, “Piel de archivo,” Revista Dossier 29 (2015): 28. ↩

- The bibliography on these topics is extensive. Key works include Allan Sekula’s “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (Winter 1986): 3–64; and Marianne Hirsch’s identification of an “archival turn” in aesthetic practices shaped by the aftermath of collective historical trauma in The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (Columbia Univeristy Press, 2012). Numerous theorists have examined the relationship between photography and archival documents, as well as the dynamics of archives and counter-archives. For an overview of the intersection between canonical archival theory and contemporary artistic practices, see Okwui Enwezor, Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art (New York: International Center of Photography, 2008); and Cheryl Simon, “Introduction: Following the Archival Turn,” Visual Resources 18, no. 2 (2002): 101–107. For more on the repurposing, recontextualization, and use of archival sources in contemporary art photography, see Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse,” October 110 (2004): 3–22; Sarah Bassnett, “Archive and Affect in Contemporary Photography,” Photography and Culture 2, no. 3 (2009): 241–51; and Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (Columbia University Press, 2012). ↩

- Bonadies, in discussion with the author, January 3, 2025. ↩

- Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton University Press, 2010), 20. ↩

- Las personas y las cosas had two solo exhibitions, both curated by Jesús Fuenmayor. The second, held at The Private Space (Barcelona, 2010), featured fewer photographs but maintained a similar presentation without labels. Several articles and reviews on the exhibitions were published, including a catalogue text by Lisa Blackmore: “Ángela Bonadies: la archon caprichosa,” in Las personas y las cosas/People and Things (The Private Space Books, 2010). Bonadies, in discussion with the author, January 3, 2025. ↩

- “A romantic idea of belonging and the beginning of the contemporary form of collecting.” See note 3. ↩

- The archives included: Archivo Fílmico de la Cinemateca Nacional, Archivo del Museo de Ciencias Naturales, Archivo Fotográfico Revista Shell at the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, Banco Municipal de Sangre, Colección Banco Mercantil, Colección Ornitológica Phelps, Museo Sefardí de Caracas Morris E. Curiel, and Sociedad Venezolana de Ciencias Naturales, all in Caracas; Museo Estación Biológica de Rancho Grande, Parque Nacional Henri Pittier, Maracay; the orchid collection at Villa Planchart, El Cerrito; and two private collections. Bonadies, in discussion with the author, January 3, 2025. ↩

- Bonadies notes that Las personas y las cosas has had two phases: its exhibitions in 2009 and 2010, and the current publication of individual images. Initially withholding locations, she now includes them to emphasize the series’ role in documenting the state of Venezuelan archives during the crisis. For this reason, I have also included the locations in the captions. Bonadies, in discussion with the author, December 13, 2024. ↩

- “Bonadies deterritorializes the origin of the documents to insert them into a new narrative montage.” Muñoz Porqué, “Del objeto.” ↩

- Amaya and Marín, “What Can Archives.” ↩

- Hal Foster quoted in Cristina E. Pardo Porto, “Counter-Visuality and Affect in Pulso: Nuevos registros culturales (2020–present) by Muriel Hasbun,” Istmo: Revista Virtual de Estudios Literarios y Culturales Centroamericanos 43 (2021): 136. For Foster, the “archival impulse” in contemporary art, or “archival art,” connects elements disconnected in time and space. This approach establishes a system with its own internal structure and archival notation, reflecting on the challenges of preserving cultural memory—an issue echoed in Bonadies’s work and characteristic of postmodernity’s perceived failures. See Foster, “An Archival Impulse,” 21; and Hirsch’s discussion of Foster in The Generation of Postmemory, 227–28. ↩

- Foster quoting Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn in “An Archival Impulse,” 10. ↩

- Didi-Huberman’s development of the concept of “montage” extends beyond a single juxtaposed image to function as a form or method, where the superimposition creates a complex layering of heterogeneous times that allows for “taking position.” For more, see Georges Didi-Huberman, The Eye of History: When Images Take Positions, trans. Shane B. Lillis (MIT Press, 2018). ↩

- Molly Kalkstein, “Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas: On Photography, Archives, and the Afterlife of Images,” Rutgers Art Review: The Graduate Journal of Research in Art History 35 (2019): 57–61. ↩

- Muñoz Porqué, “Del objeto.” ↩

- Lisa Blackmore, “Ángela Bonadies: la archon caprichosa.” For an analysis of contemporary Venezuelan political and feminist art that challenges “ideological apparatuses” from the perspective of humor, see Tatiana Flores, “Reír por no llorar: Black Humor in Contemporary Venezuelan Feminist Art,” in Humor in Global Contemporary Art, ed. Mette Gieskes and Gregory H. Williams (Bloomsbury, 2024), 189–207. ↩

- “A staging that is not quite one, but seems to be, that whispers fictions to us through photography . . . is a way of showing that generates other narratives.” Bonadies, in discussion with the author, October 27, 2020. ↩

- Blackmore, “Ángela Bonadies: Periférico Caracas/Arte Contemporáneo.” ↩

- Cristina E. Pardo Porto and Oscar A. Pérez, eds., Plants and Animals in Latin American Cultural Production (University Press of Florida, 2025). ↩

- For more on animals in the archive, see Zeb Tortorici, “Animals and Archives: Making Sense of the Discurso Filosofico Sobre el Lenguage de los Animales,” e.mispherica 10, no. 1 (Winter 2013). ↩

- “A little asleep until we take it out or touch it, see it.” Bonadies, in discussion with the author, October 27, 2020. ↩

- Amaya and Marín, “What Can Archives.” ↩

- “Depend[ing ↩

- “The ‘natural’ state of archives and in discovering . . . the absurdity of their permanence without destination or functionality.” Muñoz Porqué, “Del objeto.” ↩

- Colette Capriles, “La excepción y la ruina,” Trópico Absoluto, July 15, 2022. ↩

- Blackmore, “Ángela Bonadies: Periférico Caracas/Arte Contemporáneo.” ↩

- “Outside the heroic praise of the mythological construction of the nation.” Bonadies, in discussion with the author, October 27, 2020. ↩

- Bassnett, “Archive and Affect.” ↩

- In a previous article, I explored how contemporary Latinx photographic practices reframe “official” archives by addressing broader historical contexts and engaging personal history through the affective power of imagery. See Pardo Porto, “Counter-Visuality and Affect,” 135. ↩

- For scholarly perspectives, see Alicia Ríos, Nacionalismos banales: el culto a Bolívar; literatura, cine, arte y política en América Latina (Iberoamericana-IILI, 2013) and Irina R. Troconis, The Necromantic State: Spectral Remains in the Afterglow of Venezuela’s Bolivarian Revolution (Duke University Press, 2025). ↩

- Maia Gil’Adí, “Alexander Apóstol: Phantasmagoric Landscapes and Aesthetics of the Unfinished in Global Venezuelan Imaginaries,” ASAP/J, February 21, 2024. ↩

- “That classification suggested to me the possibility of describing a country through ‘the things’ it keeps and safeguards, that it classifies and values.” Bonadies, in discussion with the author, October 27, 2020. ↩

- The deterioration of archives in Venezuela has inspired diaspora artists to address similar themes. In Colombia, Venezuelan archivist and photographer Vilena Figueira explores the preservation of cultural objects and heritage amid Venezuela’s crisis. Her 2016 series La custodia, el cuerpo de la memoria examines displacement in memory and image archives over time. ↩

- By mid-2024, nearly eight million Venezuelans had fled their homeland, with many making the journey on foot through treacherous routes such as the Darién Gap and across the Colombian border. Colombia remains one of the largest host countries. Globally, more than one million have sought asylum, and over 230,000 have been officially recognized as refugees (see Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, accessed June 16, 2025.). These figures underscore the scale of the crisis and the widespread displacement driven by sustained political repression, economic collapse, and systemic scarcity in Venezuela. For an overview of the recent history of the Venezuelan migration crisis and the theme of diaspora and exile in contemporary Venezuelan art, see Irina R. Troconis, “Pepe López’s Crisálida: Memory, Materiality, and Loss in the Venezuelan Diaspora,” Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture 7, no. 1 (2025): 4–25; and Cecilia Fajardo-Hill, “Inner/Outer Exile in Contemporary Venezuelan Art,” Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas 54, no. 2, (2022): 194–205. ↩

- Bonadies, in discussion with the author, October 27, 2020. ↩

- Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Duke University Press, 2014). ↩

- “The place is left behind, but never abandoned.” Bonadies, in discussion with the author, October 27, 2020. ↩

- Ann Cvetkovich, “Photographing Objects as Queer Archival Practice,” in Feeling Photography, ed. Elspeth H. Brown and Thy Phu (Duke University Press, 2014), 280. ↩

- For the relationship between affect and photography, see Elspeth H. Brown, Thy Phu, and Andrea Noble, “Feeling in Photography, the Affective Turn, and the History of Emotions,” in The Routledge Companion to Photography Theory, ed. Mark Durden and Jane Tormey (Routledge, 2019), 20–36. For more on “feeling” as both a haptic/tactile and emotional experience in photography, see Margaret Olin, Touching Photographs (University of Chicago Press, 2011); Tina M. Campt, Image Matters (Duke University Press, 2012); and Brown and Phu, Feeling Photography. ↩

- Blackmore, “Ángela Bonadies: la archon caprichosa.” ↩

- Blackmore, “Ángela Bonadies: Periférico Caracas/Arte Contemporáneo.” ↩

- Amaya and Marín. “What Can Archives.” ↩

- “The fact of being in front of a space that says something, but above all leaves many things unsaid.” Bonadies quoted in Muñoz Porqué, “Del objeto.” ↩

- For an exploration of art, oil cultures, and modernity in Venezuela, see Sean Nesselrode Moncada, Refined Material: Petroculture and Modernity in Venezuela (University of California Press, 2023); and Santiago Acosta, “We Are Like Oil: An Ecology of the Venezuelan Culture Boom, 1973–1983” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2020). ↩

- “The Shell archive, in disseminating a “cheerful and progressive vision, despite the coexistence with the military dictatorship,” insisted on “naturalizing a photographic code that, in its documentary expression, sought to be a trace and, in the case of the 1950s in Venezuela, a certificate of the presence of modernity.” Blackmore refers to the dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez (1952–58), marked by political repression and censorship alongside ambitious urban and infrastructure modernization. Blackmore, “Ángela Bonadies: la archon caprichosa.” ↩

- “Rural space and urban space, Europe and the Americas, men and women, first world and third world.” Bonadies, in discussion with the author, October 27, 2020. ↩

- Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Duke University Press, 2011). ↩

- “The affective relationship with the archive turns every reading into a counter-archive or a rejection of a single, definitive reading.” Bonadies, in discussion with the author, October 27, 2020. ↩

- Inventarios was exhibited at Sala Mendoza, Caracas, as part of Contra/sentido: nueva fotografía venezolana (2003), curated by Ruth Auerbach. In 2004, Bonadies received the Premio Latinoamericano de Fotografía Josune Dorronsoro for this series. ↩

- Bonadies, in discussion with the author, January 3, 2025. ↩