From Art Journal 76, no. 2 (Summer 2017)

On November 15, 2016, a “National Day of Action,” demonstrators in cities from Los Angeles to New York took to the streets in support of the efforts of the Standing Rock Sioux to block construction of the Dakota Access oil pipeline (DAPL). According to tribal leaders, the presence of the pipeline constitutes a dire threat to the tribe’s water supply, and will desecrate scores of sacred, historical, and cultural sites along its intended 1,172-mile route. From April 2016 to February 2017, thousands of Native activists and their allies occupied protest camps along the path of the pipeline, less than a mile beyond the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. At the time of this writing, the encampments are vacant; the Trump administration, however, has expressed its intention to complete the construction of the pipeline as part of a general rollback of environmental policy that includes the withdrawal of the United States from the Paris 2015 climate agreement. No matter the outcome of the crisis, international support for the DAPL resistance movement has moved issues of Indigenous sovereignty and land and water rights into the public consciousness to a degree not seen in the United States since the standoff at Wounded Knee in 1973.1 Whether the attention of the larger public to such critical matters can be sustained is another question. Like the call to action generated by Black Lives Matter, the DAPL protests and the larger Idle No More movement, which began in Canada in 2012 and spread to the United States, expose ugly foundational truths of our nations’ histories, in the latter case the persistent and pervasive abrogation of the rights of Indigenous peoples in North America.

Twenty-five years ago, the occasion of the Columbian Quincentennial brought a convergence of Indigenous politics and art world discourses. Against the backdrop of the wider culture wars of the 1990s, the five-hundredth anniversary of the “discovery” of the New World marked 1992 as a specifically Indigenous moment, providing a space for reflection on the legacies of colonialism and the survival of Indigenous peoples and cultures. Native artists seized the platform the Quincentennial provided, producing scores of works that addressed genocide, land loss, and the ongoing assault on Indigenous sovereignty in a heady rush of exhibitions including Indigena and Land, Spirit, Power in Canada, and The Submuloc Show/Columbus Wohs in the United States.2 As part of this larger groundswell, the Fall 1992 issue of Art Journal was devoted to the topic of “Recent Native American Art.” Coedited by the critic and art historian W. Jackson Rushing III and the Cherokee painter Kay WalkingStick, the issue stressed the ways in which contemporary Indigenous art practices resonated with the emerging discourses of the art world—e.g., multiculturalism, increasing demand to diversify mainstream institutional and curatorial practices, and a nascent globalism surfacing in the arts and culture generally. The events of this twenty-five-year span are the focus of three of the longer essays in this current volume, invited contributions from four Native and non-Native scholars and curators: Kathleen Ash-Milby, Ruth Phillips, Jessica Horton, and Candice Hopkins.

If the Columbian Quincentennial (and this marking of the twenty-fifth anniversary of it) seems to indicate a preoccupation with the past, this is not borne out in the essays included here, let alone in the discourses of contemporary Indigenous art. Many of the works included in the Quincentennial exhibitions, for example, were notable for their emphasis on an active sense of presence and a promise for the future; the same can be said for the works of art and criticism herein. Then and now, the language of contemporary Indigenous art continues to be one of survivance—a term popularized by Anishinaabe author Gerald Vizenor in his 1994 book Manifest Manners: Postindian Warriors of Survivance.3 Vizenor’s neologism combines concepts of survival and resistance, positioning contemporary Indigenous people as not merely present but thriving, resisting oppression, refusing to be marginalized, and actively asserting their sovereignty as nations.

Indeed, the twenty-five-year period bracketed by 1992 and today—and by two issues of Art Journal dedicated to contemporary Indigenous art in North America—has seen an efflorescence of Indigenous art practice and discourse. As Ash-Milby, Phillips, Horton, and Hopkins demonstrate, Indigenous artists, curators, and critics have stepped into the global spaces of the contemporary art world, exhibiting at Documenta in Germany, biennials in Venice and Sydney, and numerous other international exhibitions. Also important, even as Indigenous professionals have increasingly participated in the institutions of the contemporary art world—an art world that is much more decentered and transnational than it was twenty-five years ago—they have not relinquished claims to cultural autonomy and sovereignty based in their status as aboriginal peoples. Engaging with a transnational network of artists and institutions, Indigenous artists from Canada and the United States have found common ground for collaboration with artists from Australia, Aotearoa/New Zealand, and other settler states, and together have formulated a practice of indigenous visual sovereignty around the globe. As Hopkins writes, for example, the 2013 exhibition Sakahàn: International Indigenous Art at the National Gallery of Canada featured the work of eighty artists from sixteen countries, and it was conceived as only the first in a series of five recurrent exhibitions on the scale of Documenta or the Venice Biennale.4 In the process of developing a truly global discourse of Indigeneity, however, scholars, artists, and activists have been forced to reckon less with postcolonialism than with the situation of a persistent hegemonic settler state, even in the flattened spaces of transnational capitalism. Like their peers in Latin America, Indigenous artists in North America have taken on the rhetoric and project of decolonization, suggesting that much work remains to be done in the United States and Canada, as in Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand, to reconcile the legacies of settler colonialism and to prepare for an Indigenous future.

In the still-contested spaces of the contemporary art world, the rush to the global has sometimes failed to recognize histories intentionally obscured by ongoing settler colonial regimes, which even now seek to delegitimize Indigenous sovereignty, land and water rights, and cultural survivance. The project of decolonization requires that we ask: How can the institutions of the art world —from curatorial practices to theory—be indigenized? How can key concepts, practices, and networks be fashioned to serve Indigenous communities and prerogatives? How might we move beyond the limitation of contemporary discourse, to acknowledge and embrace Indigenous notions of time and temporality, and approaches to art media and practice? How might we forward a global and contemporary art history that recognizes Indigeneity as central and vital in amulticentered contemporaneity, and how can the very notion of “the contemporary” be reframed to reflect an Indigenous cultural and environmental politics?

The essays in this issue of Art Journal provide compelling examples of decolonial art historical and critical practices. Kate Morris and Horton both bring aspects of critical theory developed outside the sphere of Indigenous art studies (configurations of historical trauma and the Anthropocene, respectively) into contact with contemporary Indigenous art practices and movements. Heather Igloliorte, on the other hand, proposes a framework for interpreting Inuit art history from a perspective based in Indigenous knowledge. Arguing that the Inuktitut conception of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (“Inuit traditional knowledge”) refuses the distinction between traditional and contemporary art practices, Igloliorte allows us to understand the work of all Inuit artists as a perpetuation of “living knowledge.” Like Igloliorte, Sherry Farrell Racette focuses on the extension of tradition into contemporary art practice, though Racette’s attention is drawn to instances of “truth telling and visual activism” in particular, and her essay considers contemporary works in light of recent developments in federal Indian policy and the formation of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In her essay “Diversifying Sovereignty,” Jolene Rickard also considers the exercise of Indigenous knowledge and the mobilization of the traditional as interventions into settler colonial, global, and transnational spaces; she stresses that sovereignty is not simply a matter of legal jurisprudence, but is a form of action that stems from Haudenosaunee concepts of natural law. Dylan Robinson, a sound and performance scholar, takes to heart Rickard’s notion of a fully embodied Indigenous sovereignty (he terms this “sensate sovereignty”). Expanding on his earlier research into “site singing” —Native artists and performers singing to places—Robinson turns in his essay to the study of text-based public artworks. His essay addresses the agency of artists and the experience of both Native and non-Native spectators with regard to works that include untranslated Indigenous language text. Robinson regards the refusal of translation as an exercise of self-determination; this is especially germane to the perception of works that are intrinsically rooted in the landscape.

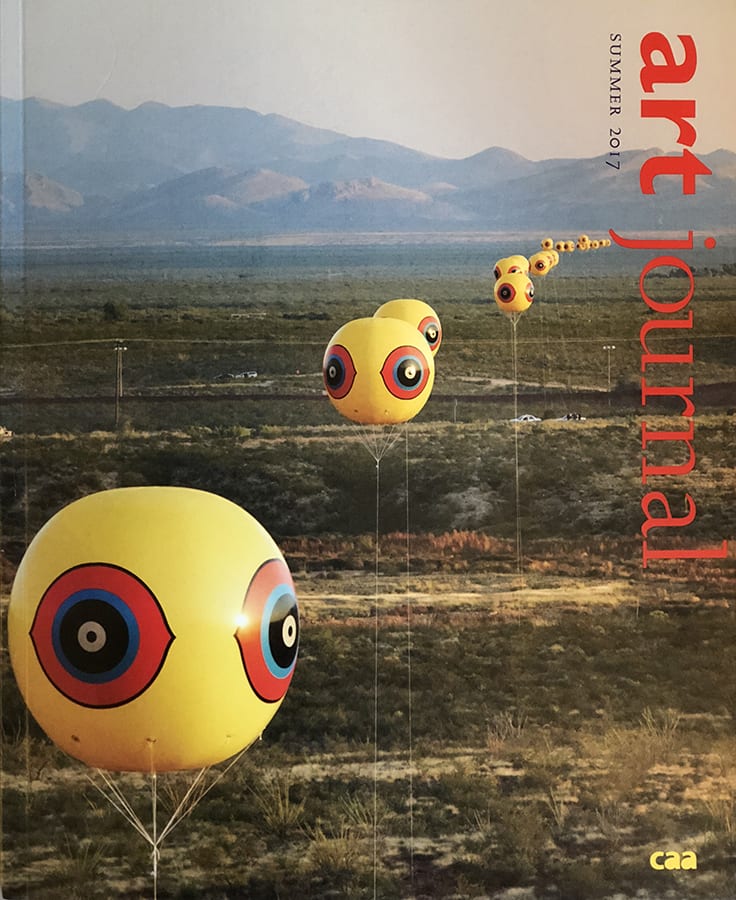

This issue (with associated elements at Art Journal Open) features an artists’ project from Postcommodity, a multidisciplinary collective that was also featured in Documenta 14 and the Whitney Biennial in 2017. For Art Journal, Postcommodity artists Raven Chacon, Cristóbal Martínez, and Kade L. Twist contribute a collection of sketches from past work, future works, and “lateral work” created for an alternate Postcommodity universe. Their work also graces the front and back covers of the issue. Marie Watt, best known for her multimedia works and community-based practices, contributes a piece in which she is interviewed by Joseph Beuys’s coyote—the influential artist’s canid collaborator in the 1974 performance/installation, I Like America and America Likes Me. In her interview, Watt touches on relational aesthetics, dematerialized objects, personal histories (her own and those of others who contribute heirloom blankets and their stories to her projects), and the symbolism of specific works such as the Trek and Talking Stick series. Coyote’s presence—an intriguing acknowledgement of nonhuman agency—is also felt throughout the essay, as a critique of modernism’s relentless appropriation of Indigenous culture and a deliberate reclamation of the part of the Trickster.

The uncertain outcome of the DAPL protests—and the uncertain future faced by all people, nonhuman beings, and our natural environment—remind us that we are indeed living in challenging times. Now more than ever we need to hear the voices of contemporary Indigenous people. The vital and engaged practices of contemporary Native artists discussed in this issue offer proof (and demonstrate effective means) of survivance: they are affirmations of identity, dignity, self-determination, and community in a global society.

Bill Anthes is a professor in the Art Field Group at Pitzer College in Claremont, California. He is the author of Native Moderns: American Indian Painting, 1940–1960 (2006) and Edgar Heap of Birds (2015), both published by Duke University Press, and he is a member of the editorial board of American Indian Quarterly.

Kate Morris is associate professor of Native American and contemporary art at Santa Clara University, and the president of the Native American Art Studies Association. She is the author of the forthcoming book Shifting Grounds: Landscape in Contemporary Native American Art, from University of Washington Press.

- In capitalizing the term Indigenous, we are following recent practice by scholars and activists recognizing Indigeneity as a politicized positionality, and respecting and supporting the struggles of Native communities in North America, as well as globally. See Glen Coulthard, Red Skins, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014). ↩

- Lee-Ann Martin and Gerald McMaster, eds., Indigena: Contemporary Native Perspectives, exh. cat. (Hull: Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1992); Robert Houle, Diana Nemiroff, and Charlotte Townsend-Galt, Land, Spirit, Power: First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada, exh. cat. (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1992); Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, The Submuloc Show–Columbus Wohs: A Visual Commentary on the Columbus Quincentennial from the Perspective of America’s First People, exh. cat. (Phoenix: Atlatl, 1992); and Christopher Scoates and Richard Bolton, eds., Green Acres: Neo-colonialism in the U.S., exh. cat. (St. Louis: Washington University Gallery of Art, 1992). ↩

- Gerald Robert Vizenor, Manifest Manners: Postindian Warriors of Survivance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), later reissued as Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance. ↩

- While most communication and collaboration has taken place among artists and curators in former territories of the British Empire, Sakahàn signalled an expanded notion of settler colonialism, including in the exhibition indigenous-identified artists from Latin America, Finland, India, Japan, Taiwan, and other nations. ↩