From Art Journal 76, no. 2 (Summer 2017)

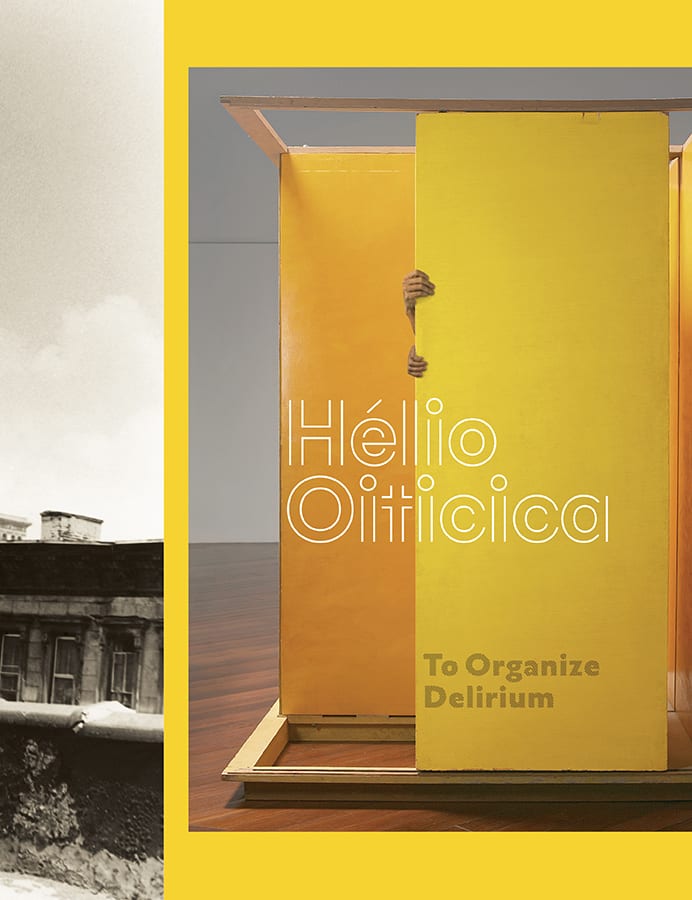

Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium

Exhibition organized by Lynn Zelevansky, Elisabeth Sussman, James Rondeau, and Donna De Salvo, with Anna Katherine Brodbeck. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, October 1, 2016–January 2, 2017; Art Institute of Chicago, February 19–May 7, 2017; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 14, 2017–October 1, 2017

Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium

Exh. cat. With texts by Lynn Zelevansky, Elisabeth Sussman, James Rondeau, Donna De Salvo, Adele Nelson, Guilherme Wisnik, Martha Scott Burton, Anna Katherine Brodbeck, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Frederico Coelho, Sérgio B. Martins, and Irene V. Small. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Museum of Art, and Munich: DelMonico Books/Prestel, 2016. 320 pp., 291 color ills. $75

Visiting Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium at the Carnegie Museum reminds us that the success of the current Latin American canon has marginalized a decade of one of its most prominent artists’ work. Neither geometrically abstract nor explicitly political-conceptual in its approach, the 1970s art of Hélio Oiticica (1936–1980) does not fit neatly within the current discourse of Latin American art history. Mostly unfinished and ephemeral, reflecting a precarious moment of self-imposed exile, Oiticica’s work from this period has rarely been shown in the United States and has received scant scholarly attention.1 This exposes a powerful irony in the career of Oiticica, as his long-sought marginality—first encountered in the Brazilian favelas in 1964—was actually fulfilled in New York, the center of the art world, where vestiges of the time he spent there would remain for the most part unseen.

To encounter this lesser-known Oiticica is to grasp that more than twenty years after Latin American art famously left the coatroom of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, US institutions overlook much of its legacy.2 By 2017, major US collections have presented the artist’s trajectory from Concretism to Neconcretism, highlighting his redefinition of the art object as an intrinsically participatory experience. However, the work made during his New York years (1971–78) and his brief return to Brazil before his untimely death (1978–80) has remained obscured. Part of the explanation for the elision of Oiticica’s 1970s production lies in the success of the Latin American canon itself, firmly anchored in geometric abstract and political art. The artist’s participation in the Concrete and Neoconcrete vanguard groups in Rio de Janeiro during the 1950s and 1960s undeniably helped to construct and solidify the concept of Latin American art that now excludes his New York period. Works such as the Metaesquemas (1957–58) and the celebrated banner, Be an Outlaw, Be a Hero (1968) are by now part of a global art history, granting a multiple modernity if not a post factum genealogy for today’s participatory works described under the rubric of “relational aesthetics.” Yet the ubiquity of these canonical works obfuscated Oiticica’s later production, excising the dominant narrative based almost exclusively on participatory works from his Neoconcrete phase. Thus, it is a happy surprise to walk into the Carnegie galleries and encounter these less familiar artworks, never before comprehensively exhibited in the United States.

By choosing to emphasize this last decade in a retrospective exhibition, Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium juxtaposes the artworks with works from his earlier and most famous period, inviting us to reassess the artist’s trajectory beyond the Neoconcrete mythology. This opportune decentering is promoted by a revised chronology that emphasizes the later part of the 1970s, after the artist had participated in the groundbreaking show Information (MoMA, 1970) and moved to New York while sponsored by a Guggenheim fellowship. The more inclusive chronology of Oiticica’s career is present in the galleries and more clearly delineated in the catalogue, in which essays and artworks are divided into the periods 1955–68 (encompassing his Concrete and Neoconcrete production and canonical pieces like the Parangolés), 1969–73 (marked by large, participatory environments and new-media work made for the most part in London and New York), and 1973–80 (a period that includes the experiments with cocaine and the penetráveis or “penetrables” done once he was back in Brazil). Examining these three phases, an established team of scholars from Brazil and United States avers that the scarce attention Oiticica received while in New York is a thing of the past. The English catalogue effectively rewrites art history by historicizing the complete trajectory of one of Latin American’s most acclaimed stars.

The challenge made by Oiticica’s 1970s artworks to the limits of the white cube further explains the long absence of a comprehensive display. Oiticica works during this period display an increasing push toward the rejection of the optical as the central mode of artistic experience. The dominant understanding that the 1970s were his “lost decade” is revised and subverted in this exhibition. During these years, Oiticica in fact created an excess of projects, albeit projects that escape easy control and are seldom fully executed. Much of his art from the period is thus difficult to display. Adding to these inherent challenges was the destruction of a large portion of his legacy in a 2009 fire at the Foundation Projeto Hélio Oiticica in Rio. In light of these obstacles, an Oiticica lacuna is less mysterious. How does one exhibit a partially destroyed production, the remnants of which also pose such inherent difficulties for curators? Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium takes the challenge and helps decenter the myth of a Neoconcretist, participatory Oiticica. But how does one organize such an oeuvre in an institutional space?

Before entering the gallery, the visitor is greeted by a projection of Apocalipopótese (1968). The video documents the collective artistic experience that took place in Rio de Janeiro’s iconic gardens designed by Roberto Burle Marx and adjacent to Rio’s Museum of Modern Art, where Oiticica started his career with lessons from the painter Ivan Serpa, winner of the first São Paulo Biennial. Taken months before the artist traveled to London, the footage is vital to contextualize Oiticica’s practice as a participatory experience beginning in Brazil. The display of Apocalipopótese amid tropical plants also reminds the visitor of his anti-institutionalism; Oiticica was, after all, an artist who affirmed that “the museum is the world; it is the daily experience.”3

Inside the gallery, the first room displays the canonical 1955–68 Concretist and Neoconcretist production. This body of work engages formally with shape and color and is undeniably the most visually striking room in the exhibition. These are also the works that are more familiar to the public and were, for example, carefully displayed in Oiticica’s last US solo show, Hélio Oiticica: The Body of Color (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2006–7). On the walls the visitor could contemplate early geometric works that compose the series Sêcos (1956–57) and Metaesquemas. These works on paper are beautifully juxtaposed with the sculptural Spatial Reliefs (1960), Bilaterals (1959–60), and Nucleus (1961–63), the last placed in the middle of the gallery, floating in the space. There is also the maquette for the Hunting Dogs Project (1961)—a never-built environment with five architectural constructions named Penetráveis and featuring works by the poets and fellow-Neoconcretists Ferreira Gullar and Reynaldo Jardim. The Hunting Dogs Project preannounces not only the increasingly immersive nature of Oiticica’s production, but also the challenges for exhibitions showing his oeuvre: a high pedestal, a device that Neoconcrete artists categorically rejected, frustrates an aerial view of the model. This is not the only instance in which Oiticica’s production is at odds with traditional museographic display.

Throughout the show, we are reminded of the difficulties and ironies of displaying such works. Pinned against the wall are the original Parangolés (1964–68), conceived as objects that required the body to operate; segregated on short bases are the famous Bólides, which the artist believed to embody an ethical position as they were integrated into the world. That some of the artworks are post-fire reconstructions (all duly flagged in the labels) poses a further dilemma and raises the question of the destiny of these new pieces post-exhibition. The iconic installation Tropicálica (1967) concludes this first room, the environment that, defying kitsch, mashes together live parrots, sand, tropical plants, poems by Roberta Camila Salgado, TV sets, and penetrables. The visitor meanders through the paths of the environment, swayed by Caetano Veloso’s song of the same title, named for Oiticica’s work. The Portuguese phrase painted on the door of one of the structures, “Purity is a myth,” almost seems to assuage our longing for original material and our increasing concerns about the commodification of Oiticica’s legacy.

In the catalogue, Adele Nelson revises the Concrete period, associating Oiticica’s early work with Paul Klee rather than with the ubiquitous references to Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian. Guilheme Wisnik subsequently examines Tropicália, placing the artwork in the larger context of the countercultural and musical movement in Brazil during the years of dictatorship. Both essays are excellent additions to a vastly studied phase.

The next rooms remind us that Oiticica’s career extended much beyond his canonized work, with the display of art from the New York years. Created and first shown mostly in the semiprivate environment of his loft on Second Avenue, which he called Babylonests (a conflation of Babylon, the artist’s nickname for New York, and Nests, the environmental pieces famously shown in Information), these pieces conflate working and living, tearing down the boundaries between life and art. They demand a temporal engagement at odds with the conventional gallery time and suggest why this post-Brazil body of works has until now been estranged from the current canon. Yet the facsimiles of The Subterrania Notebook (1971), the experimental film Agrippina Is Rome-Manhattan (1972), and the slide series Neyrótica (1973) demonstrate that these works display strong connections with the contemporaneous New York experimental scene, a period including Andy Warhol’s films (which fascinated Oiticica). One of the only creations of this period that was realized and exhibited in Brazil, Filter Project—For Vergara (1972), makes evident the exchanges between an exiled Oiticica and the artistic scene in his home country. The large-scale maze bombards the participant, mixing the sounds of radio and TVs with recordings of poems by Haroldo de Campos and of Gertrude Stein’s reading of The Making of Americans. The modulated color grid of earlier penetrables, previously formed by cheap materials such as nylon curtains and plastic walls, is now dematerialized into pure light. After being immersed in blues and yellows, the participant can literally ingest color, drinking an equally artificial orange juice before leaving the environment. The augmentation of the sensorial experience through an increased use of technology illustrates one way in which New York affected his work.

The catalogue section assigned to these years gives life to the meager imprint that remained from Oiticica’s stay in New York, showing that the relative invisibility of this period should not be equated with ostracism. James Rondeau explains how Oiticica’s barracões, structures named after the sheds where preparations for the Rio Carnival take place, were constantly reinvented. From their conception as immersive environments that could shape consciousness via a synesthetic experience, as in early projects such as Hunting Dogs, to the effervescent space of Babylonest, the barracões polemicize Oiticica’s trajectory as a continuum rather than as a progressive march toward participation. Elisabeth Sussman stresses that the marginality of these years are in fact fundamental to redefining key categories in his work, such as how the notion of the sensorial was enriched by Oiticica’s contact with New York’s new-media scene. Martha Scott Burton provides an account of the artist’s trips to the South Bronx, loosely guided by Martine Barrat and Carlos Suarez, to reveal that Oiticica’s interest in marginalized neighborhoods did not dwindle during his stay in the United States. Anna Katherine Brodbeck demonstrates that Oiticica’s sensorial experiments started in Brazil and incorporated both Latin American and US references. Mixing Brazil’s Marginal Cinema and the thinking of Herbert Marcuse and Marshall McLuhan, they conceive an eroticized subject, capable of alienating herself from alienation—enlarging our notion of the meaning of the political during those turbulent years. By surveying the artist’s participation in multiple exhibitions in Brazil, Brodbeck also aptly reminds the reader that New York’s centrality did not promptly translate into international opportunity. Finally, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz interprets Oiticica’s coinage of “Tropicamp”—a term associated with the work of Jack Smith and Mario Montez—as a means to resist the gradual commercialization of queer aesthetics in the United States during the 1970s. Elucidating how these years shaped social and ethical concerns in Oiticica’s oeuvre, this section successfully defies the “lost decade” moniker.

Among the works made between 1973 and 1980 is the famous series Cosmococas. These works employ cocaine, the sale of which seems to have been Oiticica’s main source of income in the mid-1970s. Made in collaboration with Neville D’Almeida, the enclosed environment contains hammocks, loud music, and projections of rock-and-roll album covers adorned with the white powder. Segregated inside the gallery space, CC5 Hendrix-War (1973) provides the visitor with a chance to experience both a moment of collective solitude (evoking the original context inside Oiticica’s apartment) and the friction that such works introduce into the institutional space. This friction is exacerbated with Newyorkaises (1971–77), an open archive of texts and images that began as a book project. The facsimiles cover the walls of an entire room, are mostly in Portuguese, and are placed too high on the gallery’s walls for a viewer to read. This display proves the productivity of these years, but also highlights that this work-in-progress was never truly conceived as public.

If the galleries evince the sparse retinal quality of Oiticica’s 1970s works, the catalogue helps to integrate this body of work into art history. Frederico Coelho, author of an extensive analysis of Newyorkaises in the context of the counterculture, examines Oiticica’s unfinished book.4 Sérgio Martins exposes Oiticica’s vast landscape of references that amalgamate Nietzsche and Hendrix. Cruz, in his second contribution to the catalogue, explores Oiticica’s literal and artistic use of cocaine in the context of his precarious status in New York, as a publically gay, South American dissident in exile, living under an expiring resident permit, who nevertheless considered his return to Brazil “disastrous.”

The works of the return to Brazil (1978–80) include Brutalist Manhattan—Semimagical Found Object (1978), a large chunk of asphalt in the shape of Manhattan island “appropriated” from a construction site on Avenida Presidente Vargas, a street that crosses Rio’s downtown center. The artist carefully placed the “found object” in his bathroom among other appropriations of Rio’s sidewalks. Both Brutalist Manhattan and its private display in the artist’s apartment attest to resonances of the New York period back in Rio. The exhibition also includes original photos and reenactments of the performance Counter-Bólide 1, To Return Earth to Earth (1979), in which a square wooden frame placed on the ground is filled with soil taken from another site and then removed, poetically evoking the artist’s recent experiences of displacement and exile. Finally, consider PN27 Penetrável, Rijanviera (1979), one of the few originals exhibited. Rijanviera, as the name suggests, was created in homage to the city of Rio and realized at the Hotel Méridien in Copacabana. The penetrable, like Filter Project, consists of colored walls, but also contains a floor partially filled with water and a rock garden. When it was first presented in Rio, almost forty years ago, the pump broke on the opening night and flooded the gallery. But as the visitors learn from H.O., Ivan Cardoso’s 1979 experimental film about Oiticica’s work, even a flooded floor did not discourage a plethora of friends and collaborators, from the poet Ferreira Gullar to the artist Lygia Clark, from walking through the semi-veiled penetrable. At the Carnegie the pump broke again, and it’s ironic that now the piece had to be closed to the public. By contrasting this spontaneous reenactment with Cardoso’s moving images, the visitors are given a bittersweet reminder of the consequences of the inevitable institutionalization of this period.

In the catalogue, the years in Rio are treated as a phase in its own right. Irene Small ingeniously “organizes delirium” to place Oiticica’s return to Brazil in the larger context of his work. Following patterns cherished by the artist, such as constellations and labyrinths, she demonstrates that his “invention” is immune to dilution as it transforms finished works into something generative and new. In short, Oiticica’s work cannot be reduced to a linear, static chronology. Finally, the struggles of putting together a comprehensive retrospective of Oiticica’s show are examined in Donna De Salvo’s essay. She analyzes The Whitechapel Experiment (1969), the only major museum show held during the artist’s life, and the first posthumous retrospective, the 1992 Hélio Oiticica show at the Witte de With in Rotterdam. This last contribution effectively embodies the ambitions of the exhibition when it theorizes the later part of Oiticica’s work and historicizes the whole of his legacy.

When the visitors leave the galleries at the Carnegie Museum, they realize that the exhibition’s chronology was positively interrupted. Due to the sheer size and nature of some of the 1960s production, some artworks were placed in a large atrium below. The re-created large-scale installations Eden (1969) and Appropriation—Snooker Room, after Van Gogh’s “Night Café” (1966), together with some reproductions of Parangolés, the celebrated interactive capes, invite the public to finally experience the works in a fashion closer to Oiticica’s intentions. Viewing Oiticica’s celebrated Neoconcrete pieces after being exposed to the whole of his production cleverly connects these participatory works both to his earlier formal experiments (Eden, viewed from above the atrium, clearly transforms Mondrian into planes materialized in space) and to his last production in Brazil (by comparing, for example, his taste for appropriating items difficult to transport, such as pool tables and asphalt). These associations are important, especially as they undermine the Neoconcrete myth of an isolated moment of radical experimentation—a mythology that has dislodged both his earlier formal experiments with color (which were categorically dismissed by the artist himself in 1972) and the later 1970s phase. The circularity helps us to avoid the pitfalls of inflecting a progressive reading into Oiticica’s artistic production, a progression that is then suddenly interrupted when his 1970s artworks no longer fit the canon. By placing the noncanonical pieces inside the galleries, the exhibition successfully rewrites Oiticica’s narrative in more meandering ways—an apt metaphor for an artist who aspired to the great labyrinth.5

Camila Maroja is the Kindler Distinguished Historian of Global Contemporary Art and an assistant professor of art and art history at Colgate University.

- Although Oiticica scholarship in English continues to grow, as attested by Irene Small’s excellent Hélio Oiticica: Folding the Frame (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), most of the attention is given to his work of the 1950s and 1960s; the English-language literature on the 1970s concentrates on Oiticica’s cinematic experience, including the famous Cosmococas series. See, for example, Carlos Basualdo, Hélio Oiticica: Quasi-Cinemas (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2001); and Sabeth Buchmann and Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Hélio Oiticica and Neville D’Almeida: Block Experiments in Cosmococa—Program in Progress (London: Afterall, and Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013). The Projeto Hélio Oiticica digitized the artist’s writings, including the extensive texts and notes produced during his time in New York, before the 2009 fire. ↩

- I refer here to John Yau’s 1988 piece “Please Wait by the Coatroom,” Arts Magazine 63, no. 4 (December 1988): 56-59, rep. Out There: Marginalization and Contemporary Cultures, ed. Russel Ferguson (London: Afterall, and Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), in which Yau writes about Wifredo Lam’s La Jungla (1943) being placed outside the MoMA galleries. ↩

- Hélio Oiticica, “Posição e programa—Programa ambiental—Posição ética” (1966), in Hélio Oiticica, Aspiro ao grande labirinto: Textos de Hélio Oiticica (1954–1969), ed. Luciano Figueiredo, Lygia Pape, and Waly Salomão (Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 1986), 79. ↩

- Frederico Coelho, Livro ou livro-me: Os escritos babilônecos de Hélio Oiticica (1971–1978) (Rio de Janeiro: EDUERJ, 2010). ↩

- On January 15, 1961, Hélio Oiticica wrote: “I aspire to the great labyrinth.” The phrase was later used for the title of the posthumous anthology of his writings cited above in note 3. The title makes it clear that the earlier period of Oiticica’s trajectory is also substantially more explored in his home country. ↩