From Art Journal 76, no. 2 (Summer 2017)

The gallery, with installations by the three artists, was configured to evoke the footprint of a longhouse, a form of architecture built by the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Nation). “I made my piece in collaboration with the Santa Fe Indian School, Santa Fe University of Art and Design, Tierra Encantada High School, Institute of American Indian Arts, and other members of the Santa Fe community. I was initially inspired by research into the Mohawk ironworkers who built many of Manhattan’s skyscrapers, an abstract correlation between the structure of the longhouse and the structure of the skyscraper, and the dense living communities and neighborliness that result from both.”

Marie Watt first encountered Joseph Beuys’s work as a college student studying abroad. While working on an MFA at Yale, she wrote a reflection on the artist’s I Like America and America Likes Me from the perspective of Coyote, for a course taught by the art historian Romy Golan. In Beuys’s infamous 1974 performance, the German artist spent several days in an enclosed space at New York’s René Block Gallery with a live coyote, a large piece of wool felt, straw, gloves, a shepherd’s staff, and fifty copies of the Wall Street Journal, delivered daily during the performance. Beuys regarded his collaborator in the work, the coyote, as a descendant of the steppe wolf, whose ancestors crossed the Bering Land Bridge from Eurasia to become, like their human companions, indigenized to the Americas. For Beuys, the coyote was a figure that embodied the potential for transformation and the possibility that a European artist might become a Native North American shaman who could restore balance to a politically and ecologically troubled world. Today, Beuys’s coyote returns to North America, this time as Watt’s interlocutor.

Coyote: Most of our readers will probably know me from my work with Joseph Beuys, but I have had a very active career for centuries, working the shaman circuit here in the Americas. Beuys knew that, and he must have hoped I would lend a certain gravitas to his act when he came here, because, y’know, he thought he was a shaman, too. At least I came out better than that poor rabbit. After Beuys, I did a lot of work, mostly with Indigenous artists, such as Jimmie Durham, Edward Poitras, Harry Fonseca, and Rick Bartow. (I miss Harry and Rick.) It’s good to be back. But enough about me. I want to know about your collaborative process, but first, and thinking about Beuys, tell me . . . why blankets?

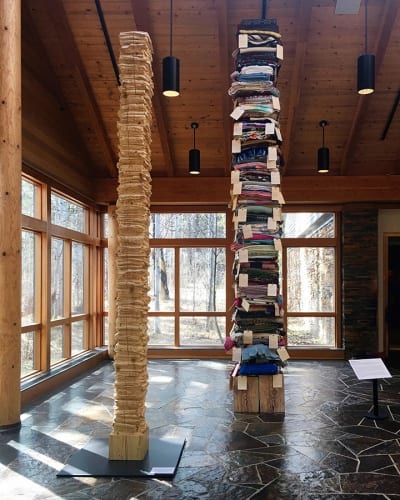

Marie Watt: I’m interested in how blankets are objects that we take for granted, but that can have extraordinary histories. I started scavenging for wool blankets from thrift stores in an attempt to construct totem- and ladder-like sculptures. I noticed that people would respond to the work by associating memories and stories of their own blankets. I like the associations the blanket columns have with ladders between sky and ground—here I’m thinking about Brancusi’s Endless Column—and in how this form might also reference linen closets and other aspects of domestic life. I also like the association of the columnar forms to the conifers and totems of the Pacific Northwest.

Blankets are also personal to me. In my tribe—I am Seneca, one of the six tribes that make up the Iroquois Confederacy—and other native communities, we give blankets away to honor people for standing witness to important life events.

Coyote: In my performance with Beuys, I had to tear that blanket away from him; it made a good pelt to sleep on in that empty gallery. But I think Beuys was also interested in them as objects imbued with energy, both actual and metaphysical. Beuys told me that when his plane crashed behind enemy lines in the Second World War, he was rescued by Tatar tribesmen and wrapped in heavy wool blankets as he was nursed back to health. [Coyote rolls his eyes a little.] Well, it makes a good story, doesn’t it?

Watt: A good story indeed [laughs]. I’m not so sure about Beuys’s shamanic transformation story, but I do believe in the notion of blankets as transformative objects (which runs counter to Freud, who thought of blankets as transitional). Blankets are universal. They are intimate objects that cover, protect, insulate, nurse, celebrate, and adorn. Despite—or perhaps owing to—their ubiquity, we often take them for granted.

Blankets receive infants into the world, and shroud us when we die. I think of worn satin bindings, stains, and mended bits as being ledger-like in the way they register dreams, child’s play, intimacy, war, and celebratory moments in life.

I am also interested in how wool blankets are made from the fleece of sheep. In my tribe, we consider animals our first teachers, so wool blankets are particularly poignant. Wool blankets don’t tend to stay square: they take on the shapes of the bodies that inhabit them. With respect to your relations, Coyote, blankets take on the historical function of animal pelts that would have preceded them.

Coyote: I’m fond of sheep myself. How did your sewing circles come about and what is involved?

Watt: Early on, I was working on large-scale wall assemblages, and I knew I wanted them to be hand-stitched: sewing machines were out of the question. With deadlines looming, I reached out to neighbors, friends, and strangers and started inviting people over to stitch. Something I really enjoy about them is that while there is no expectation to talk, I have noticed that when eyes are diverted and hands are occupied with something as familiar as cloth, stories and talk tend to flow.

My sewing circle invitation is the same today as it was in the early years: No sewing experience necessary, I will feed you, I will trade a small artist-made silkscreen print in exchange for stitches, come and go as you wish, all ages are welcome (participants have ranged in age from three to ninety-three), and share this invitation with others—friends, students, artists, anyone. The sewing circles instantly took on a life of their own. I like to think of the sewing circle as a barn-raising, where many hands make light work. I also am ready to help others with their projects, too.

Something else I love is that each person’s stitch is unique, like a thumbprint. As the threads intersect and blend, I see them as a metaphor for how we are all related. Recently, and in response to the need to involve much larger groups of participants (sixty students at the University of Washington, and over two hundred people at the National Gallery of Canada) the sewing circles have evolved in a way that really features embroidery.

For these large gatherings, I gridded out and de-assembled a work into individual pieces and provided one to each sewer. Later I reassembled the parts in my studio. What’s great about using embroidery in the sewing circles is that each person’s stitch or mark really becomes apparent.

An important side note: I don’t consider sewing circles to be aligned with sewing bees, which had their origins as missionary work, and by extension were a historical means of colonizing Indigenous girls and women. As sewing bees have evolved, so has their significance to women’s work and feminism. Sewing in community, or for that matter making objects in relational settings, is a time-honored tradition, often including women and men, that I embrace and celebrate. The history of sewing circles in relation to freedom quilts, social activism, and economic development is also incredibly important work.

At the National Gallery of Canada, 230 people took part in a three-hour sewing circle.

Coyote: I am intrigued by the idea of working with a pack. I tend to be known just as “Coyote” in the singular and most often I am seen working alone. But of course we Canidae are social creatures. All of those “lone wolves” notwithstanding, I think maybe some of my relatives invented relational aesthetics. We’re not much for sewing, though.

Watt: I’m a pretty social creature, so the notion of breaking out from a solitary studio practice and working in a pack in the context of sewing circles appeals to me. I actually think this type of multigenerational and cross-disciplinary gathering approximates the way knowledge is traditionally shared and passed down in Indigenous communities. I never know where the sewing circles will go, but I’ve participated in enough of them to anticipate learning something new and meeting interesting people. This reminds me of what Beuys said: people who want to teach should come together with people who want to learn. I’d like to add that teachers are learners and learners are teachers. The sewing circles have a whole lot of unorchestrated teaching and learning going on.

As for relational aesthetics, there is something that happens between the participants that I feel is greater than the finished piece. It’s the conversation, the food that is shared, knowledge being passed, and engaging with others. I leave, exhausted and exhilarated, feeling part of something larger. With technology now mediating so much of how we connect with others, having a moment where you can come together in a personal way has a lot of value.

The Block Museum sewing circle created material for a new commissioned work.

Coyote: So would you say that the social aspects of these works are more significant than the finished products? I’ve always been a fan of the dematerialized object.

Watt: At the moment, they’re both equally important. The social aspect is an essential part of the life of the object, but there’s still a lot of research and thought that goes into the final visual expression. When a person walks up to a work, she or he has to look closely to notice that different hands contributed to its making. But I can’t look without seeing the sewing circles and communities who participated in it. My role is sending out the invitation, “setting the table,” and letting everything else come together as it will. But even if the sewing circle is a primal/pack experience, I still tend to toil over the final narrative and image. The evidence of the sewing circle quietly persists in the finished work.

My practice is constantly evolving. If my work were truly dematerialized, it would just be your chewed-up blanket! Maybe the truth is that while I deeply admire conceptually driven work and at some point may arrive at the completely dematerialized object, I’m not there yet.

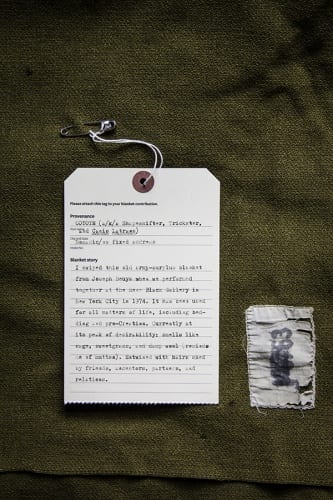

Or maybe what I’m trying to do is the opposite: to materialize the dematerialized. I did a project with the Tacoma Art Museum in 2014 in which people donated blankets and blanket stories to create a large sculpture. The blankets were to be cast in bronze, and so the material would literally be incinerated and lost in the casting process (although by bronzing them they were at the same time immortalized). For this reason, we documented each individual blanket and story and archived them as a website.

The sculpture Blanket Stories: Transportation Object, Generous Ones, Trek (2014) is composed of two eighteen-foot-tall arcs, made from bronze casts of folded and stacked blankets. Each blanket is numbered in relief so that observers can look it up on their smartphones, see what it looked like before the casting process, and read the corresponding story.

This project was my first large outdoor permanent sculpture, and I like that anyone can engage with it. Another aspect that I really like about this sculpture, and its web component in particular, is that in archiving these stories I had the opportunity to see certain recurring themes in the community’s history—stories about veterans or the military (there’s a military base just south of Tacoma), stories about settling and moving west, immigration, Indigenous stories, stories particular to this community, as well as larger themes (grandmothers, handmade blankets, and so forth).

As a result of this project, it has now become part of my practice that when I collaborate with a community on a sculpture with blankets and their stories, I consider the digital archive and website to be an integrated piece of the final work. To me it’s not a didactic tool for the institution. It’s a way for the art to exist in the world and to be accessible to anyone at any time.

“Transportation object” is the term used to classify cradleboards at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. “Generous ones” acknowledges Tacoma’s indigenous inhabitants, the Puyallup and Coast Salish People. The name Puyallup or S’Puyalupubsh means “generous and welcoming behavior to all people (friends and strangers) who enter our lands.” “Trek” reflects on slow journeys, as well as the dynamic confluence and exchange that is a part of migrating and settling. To read the stories associated with the donated blankets, see http://blanketstories.tacomaartmuseum.org, as of June 5, 2017.

Coyote: I noticed in your bio that you have an MFA in painting and printmaking, but do you consider yourself a fiber artist?

Watt: My training is as a painter and printmaker. In the course of my studies I realized that I experience the world as a tactile kinesthetic learner. This prompted me in the direction of making sculpture and installation. I don’t consider myself a fiber artist, but I do appreciate how the work crosses over. I hand-stitch things, because that is what the work requires of me. I also make work with wood, cast bronze, I-beams, and stone. I anticipate alternative materials in my future. I regularly make prints, for example this past fall I collaborated with master printer Julia D’Amario at Smith College.

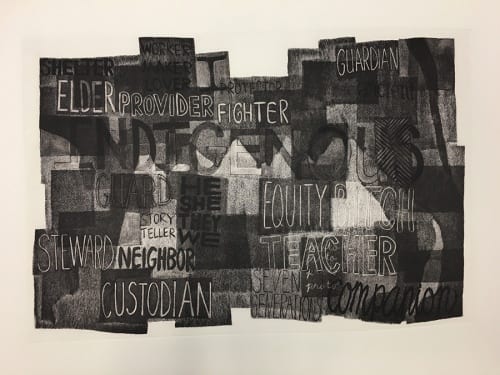

Collaborating with printer Julia D’Amario, Watt ran a small blanket construction through the press, transferred it onto a soft ground plate, etched, then further worked with dry point and burnishing for this wolf image. It was published and printed at the Smith College Printmaking Workshop. The print preceded the related sampler work, Companion Species (Fortress).

Coyote: Hey, I’m hardly one to insist on strict classifications! I’m still thinking about what you said earlier regarding the animality of blankets. Can you say more about animals as teachers?

Watt: Sure. In the Seneca and Iroquois creation story, Sky Woman falls from the sky, and as she falls, she is assisted by a motley crew of animals who help her survive on what we now refer to as Turtle Island. In acknowledgment of the way that these animals helped Sky Woman, we consider animals to be our first teachers. I think that when one is raised to think of animals as teachers and also as extensions of us—our relatives or relations—you’re less likely to be able to separate how our actions affect the environment, animals, and the natural world.

There’s also the Iroquois teaching of the Seven Generations—what we do affects not just the next generation but the next seven. Animals and the environment are really important parts of that belief system. It teaches that we have a responsibility to them, but I also think that our relationship with animals and the natural world is deeply reciprocal. In Western culture, people can enter into this conversation with some familiarity in respect to their companion animals—dogs in particular. Right now I’m really interested in dog stories (although I’m actually a cat person!) and how people relate to their dogs in a familial way. These companion relationships are a way of understanding our broader connections together. Donna Haraway addresses this history in her book, The Companion Species Manifesto.1

I’m interested in how canines can be a vehicle for telling this story about humans, animals, and the environment in my work. The beauty of it is that it’s a really old story—humans and their companions. Think Remus, Romulus, and the She-Wolf, as well as Coyote stories. In my work right now I’m exploring how canines are a portal to understanding animals as teachers in general. This is one of the reasons I was really looking forward to talking with you.

Coyote: That’s really interesting, except for the cat part of course. Can you give an example of how canines are figuring in your work? And how does this relate to some of the other references you make—to modern and contemporary art history, images of flight, etc.?

Watt: In my studio I am working on a She-Wolf piece (sans Remus and Romulus)—embroidered in sewing circles held partially at the High Desert Museum—on plaid stadium blankets, eight by thirteen feet, in which her trunk fills the canvas, so much so that her body is like a canopy that a viewer stands underneath. As viewers, we are sheltered by her body, and in a sense she is offering to nurse us.

As for images of flight, I would attribute that to my dad being an engineer at Boeing, my family’s obsession with science fiction, and being raised in the Pacific Northwest and hearing Raven stories told by my friend Roger Fernandes (from the Lower Elwha Band of the S’Klallam Indians).

There’s also a link to the Seneca clan system, in which there are four bird clans and four land-walking animal clans (traditionally, one would marry from the opposite group to keep balance: for example, I come from the turtle clan, a land animal, so I would marry someone from a bird clan). So birds and four-legged animals tie back into the idea of animals as our first teachers, and birds especially (or things that fly) are a way for me to explore the intersection of ancient and modern stories. Whether that is through astronomy and specific constellations or through science fiction, all are ways of explaining our existence, and for me, all are giving voice to material objects—baskets and blankets—that still have significance in our time. A good example might be Trek (Pleiades), which is based on a design from a basket referencing star forms, indigenous Seven Sisters stories, and also the USS Enterprise from Star Trek.

Stars are the source of so many stories and teachings for Indigenous people; but also when you look at Greek and Roman myths, a lot of those stories are referenced in astronomy and space science as well as our contemporary science fiction. I’m interested in revealing and understanding these connections between the ancient and modern and how the threads intersect.

© Marie Watt; photograph by Aaron Johanson)

“The work reflects on long journeys as well as our ancient and modern fascination with stars. The star motif in this piece draws from a design on a Native American basket; the maker is unidentified, but it is of California or Oregon origin and resides in the collection of the Hallie Ford Museum of Art. I depicted the Pleiades, or Seven Sisters, in honor of my friend Alma Nungarrayi Granites, whom I met during the Landmarks artist exchange and printmaking residency organized by the Tamarind Institute (Albuquerque, New Mexico) and the Yirrkala Art Center (Yirrkala, Northern Territory, Australia). The starship Enterprise (Enterprise-A, from the television series Star Trek) underscores intersection of the historical and contemporary, the real and mythical.”

Coyote: Your work Talking Stick is especially interesting to me, as it seems to relate again to Beuys (and that staff he used in his piece with me) in some way.

Watt: In the case of Joseph Beuys, I think of his cane or shepherd’s crook as being used in the capacity of herding and harnessing energy from alchemical props like the blankets, newspapers, and yourself as a Shapeshifter, as well as through ritualistic gestures. In contrast my sculpture or “talking stick” is more about wood, reclaimed and old-growth white pine, as a storied material and a living object (still yielding sap), as well as a touchstone for community stories, like that of blankets, that connect us. But I use the term talking stick as a double entendre as well. Historically, staves or talking sticks have been used by Native communities as a way of ensuring everyone’s voice is heard. Often a talking stick would be used in a council meeting and would be passed around, giving each person an opportunity to speak.

When I was a kid during the 1970s, my mom—an Indian education specialist for our local school district—applied this cultural wisdom in a storytelling circle she formed. In this context, the talking stick was shared by multigenerational participants—youth, parents, younger siblings, and elders. It was a tool for learning cultural wisdom, sharing stories, and developing public speaking and listening skills. My mom likes to say we have two ears and one mouth, so we are supposed to listen twice as hard.

Coyote: Well, I’m not sure I’m ready to give up my pelt just yet, but I did bring you a little gift. [Reaches into bag.] I, er . . . uh, Beuys thought you might want to have this. [Nuzzles over toward Watt a folded woolen blanket with some remnants of straw and newsprint. Sniffs.] It smells a little musty—I’ve had it for a while now.

Watt: Hey, Coyote, do you want to fill out a blanket story tag?

I want to express my gratitude to Bill Anthes and Kate Morris for their keen insights and contributions, especially in helping to shape the voice of Coyote.

Drawing from Iroquois protofeminism and Indigenous principles, Marie Watt’s work is concerned with the intersection of history, community, and storytelling. She addresses how multigenerational and cross-disciplinary conversations create a lens for understanding connectedness to place, one another, and the universe. Watt holds an MFA in painting from Yale University, and degrees from Willamette University and the Institute of American Indian Arts. She has received fellowships from the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Joan Mitchell Foundation, and Anonymous Was a Woman, among others. Selected collections include the National Gallery of Canada, Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, Fabric Workshop and Museum, Seattle Art Museum, and Denver Art Museum.

- Donna Jeanne Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2007). ↩