George W. Bush, Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors, March 2–October 17, 2017, George W. Bush Presidential Center, Dallas, Texas. http://www.bushcenter.org/exhibits-and-events/exhibits/2017/portraits-of-courage-exhibit.html.

George W. Bush, Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors. Exh. cat. New York: Crown Publishers, 2017. 191 pp, 72 color ills. Hardcover $35.00.

Like many other art historians, I have looked upon President George W. Bush’s retirement pastime of painting with interest. I was drawn to the strangeness of his early self-portraits and the awkwardness of his depictions of world leaders. But perhaps unlike other art historians, I have a personal attraction to his images of wounded military veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan. My partner is an Operation Iraqi Freedom veteran of the US Marine Corps, and I teach art history at a university where, every semester, around 20 percent of my students are either active military or veterans, most of whom served in Iraq with the US Army. I think twice when I teach bloody war images by Goya or Gardner or Dix. Some of my students have seen much worse.

Bush started painting in 2012 after reading Winston Churchill’s essay “Painting as a Pastime” (20). In the exhibition’s wall text, Bush states, “I was antsy. I figured that if painting had sated Churchill’s appetite for learning, I might benefit from it as well.” Bush primarily paints portraits. The exhibition Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors featured painted portraits of ninety-eight men and women in the Armed Forces who sustained injuries in the war in the Middle East. Bush painted this particular series at the suggestion of his painting mentor Sedrick Huckaby, himself a portraitist, who “was aware of my world leaders series, and he suggested I paint people whom I knew but others didn’t” (14). This last point sticks; one learns in the catalogue that Bush met all of his portrait subjects after they sustained their injuries.

The exhibition included sixty-six individual portraits, along with a large four-panel mural that depicts bust-length portraits of thirty-five veterans, though some subjects in the mural are repeated from the individual portraits. Bush painted the entire body of work in under a year. The work was presented in the special exhibitions galleries of the George W. Bush Presidential Center in Dallas, where the walls were all painted olive drab, reminding viewers of the military context of the exhibition; overhead track lights spotlit the paintings. This design, augmented with two looping musical soundtracks—one from an introductory video internal to the exhibition and another from a CGI wall and video blaring from the atrium—created a dramatic effect. The rooms also contained central vitrines with objects unrelated to painting, which underscored that this was not an art exhibition, but rather a highly politicized space. As Bush writes in the catalogue introduction, “I’m not sure how the art … will hold to critical eyes. After all, I’m a novice” (15). Few novice painters will ever have an exhibition, complete with full-color catalogue, at this scale.

Entering the exhibition, one first encounters a video of Bush speaking about this series. He refers to the subjects of his video as “warriors” and “volunteers,” recalls his various painting teachers, and highlights the skills one learns in the military. He notes the bravery of facing post-traumatic syndrome (PTS), emphasizing that members of the Armed Forces suffer both visible and invisible wounds. The video has a lively instrumental soundtrack that can be heard throughout the exhibition, though it fights for ear space with the equally soaring music of the digital installation in the center’s atrium. This introductory space also exhibits three portraits of Bush by his painting teachers Gail Norfleet, Jim Woodson, and Huckaby.

The first room of the exhibition contained a dozen full- or half-length portraits of wounded veterans who have participated in two of Bush’s initiatives for wounded veterans: the Warrior 100K, a mountain bike ride, and the Warrior Open, a competitive golf tournament. These portraits fully showed the wounded soldiers as amputees with prosthetic limbs. In the center of the room, an open vitrine displayed the president’s own Trek mountain bike and bag of golf clubs, highlighting that he also takes part in the Warrior 100K and Warrior Open and demonstrating the president’s personal interactions with the wounded servicemen. The second room featured many bust-length portraits in groups of three, six, or nine, along with letters to the president from some of the portrait subjects. The third room exhibited individual portraits and the mural. The fourth room had yet a few more portraits, including two paintings of the same man that seemingly represent him “before and after” PTS; the first shows a gaunt and blank face, the second a broad smile and fuller cheeks, apparently emphasizing the physical effects of PTS treatment. The room also contained an interactive wall testing the viewer’s military literacy with questions such as “What percentage of Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans suffer from a Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)?”; a Bush Warrior Center flag signed by servicemen; and a video about PTS and the role of veterans in the civilian world. The final room contained photographs of the bike rides and golf tournaments, as well as comfortable couches and copies of the exhibition catalogue. The exhibition used these artifacts as teachable objects meant to demonstrate the president’s involvement with veterans, blending art with material culture.

The Bush Center used politicized terminology throughout the exhibition, revealing a carefully considered bias. The use of the word “warrior”—in the oft-referenced Warrior athletic events, and in the texts of the —seems pointedly backward-looking, calling to mind the heroes of ancient Greek mythology rather than those of the modern military complex. The term PTS rather than PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) is used purposefully. The “D” is eliminated because the Bush Institute wants to circulate the notion that PTS can be overcome and is therefore a syndrome rather than a disorder. While the sentiment is cheerful, it erases the lingering struggles of those dealing with trauma as a disorder. Another term used repeatedly is “volunteer,” which lends a sense of altruism to military service. But members of the military are not volunteers in the modern sense of donating their time to a good cause. They are paid for their difficult work. What is more, the term “volunteer” is a pointed reminder that these men and women were not drafted into the military; they enlisted. “Volunteer” becomes military rhetoric to dissuade discontent: soldiers volunteered for this and therefore cannot complain about their lot, much less back out of their commitment.

The wall labels for each work accentuate that this painting exhibition is in a non-art setting, with interpretation limited to a few text panels and the exhibition catalogue. The wall labels list the rank of each portrait sitter, his or her name, military branch, and years served, along with the medium (mostly oil on canvas or oil on gesso board) and the dimensions of each painting. Only one painting is signed, and this is a detail internal to the painting itself. As the story goes, the sitter, Chief Warrant Officer Jeremy James Valdez, met President Bush at the Warrior 100K. Valdez had a military tattoo on his right forearm and asked President Bush to sign it; he then had that signature tattooed over the original (160). Valdez’s half-length portrait shows him with his hands clasped in front of his torso, showcasing his tattoos.

One of the problematic areas of the exhibition was the wall text, which included scant narrative of the injuries sustained or how these soldiers came to know the president. I heard several museum visitors ask the docents about various individuals shown. Asking feels a bit intrusive. One must read the catalogue to get the full stories, all of which are written by Bush. I felt uncomfortable with the skeletal bluntness of the wall texts; they blurred together, becoming almost interchangeable. The sheer quantity of numbers in the exhibition, though meant to highlight the specificity of the subjects, also muddies the experience of looking. The emphasis on percentages and statistics reaches its zenith in the room with the interactive system. I scored terribly on the quiz on veterans, and I live with one.

The paintings themselves are quite expressive, if somewhat inconsistent, likely owing to the time Bush spent on them. Bush paints at an astonishingly fast clip, and some portraits are more detailed than others. His expressionistic style also works well given the short window of time allotted to the series. The brushwork is loose and the paintings full of rich impasto, but the facial expressions are clear. Though he has overworked a few faces, Bush has nonetheless rendered the majority with fluidity and ease. For example, the lighting in the portrait of Sergeant Bryce Franklin Cole is striking in its clarity and plays well with the impasto on the canvas. Others, such as the portrait of Sergeant Daniel Casara, show a strong use of color modeling in the facial contours as well as in the backdrop.

Installation images by Melissa Warak of Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors.

According to the catalogue, Bush painted the portraits from photographs by Laura Crawford, Eric Draper, Grant Miller, Paul Morse, and Layne Murdoch (191). This method is particularly obvious in the several portraits of servicemen smiling broadly as if cropped from a group snapshot, or in the paintings where the lighting clearly mimics that of the outdoors. One exhibition docent told me that the process of sitting for a painted portrait would have been physically painful for the injured veterans. This seems plausible enough, though Bush has painted regularly from photographs in the past. Bush’s method for choosing his particular source photographs, however, remains unclear. Unlike the full-length portraits of the athlete-veterans in the first room, most of the bust-length portraits focus on the face, eliminate the background, and do not depict physical injuries. While some of the faces smile brightly, many do not. The somber images without toothy grins are the strongest paintings; they appear less tough than guarded. These paintings are more psychologically complex and, perhaps ironically, seem more rooted in the vulnerability of the veteran.

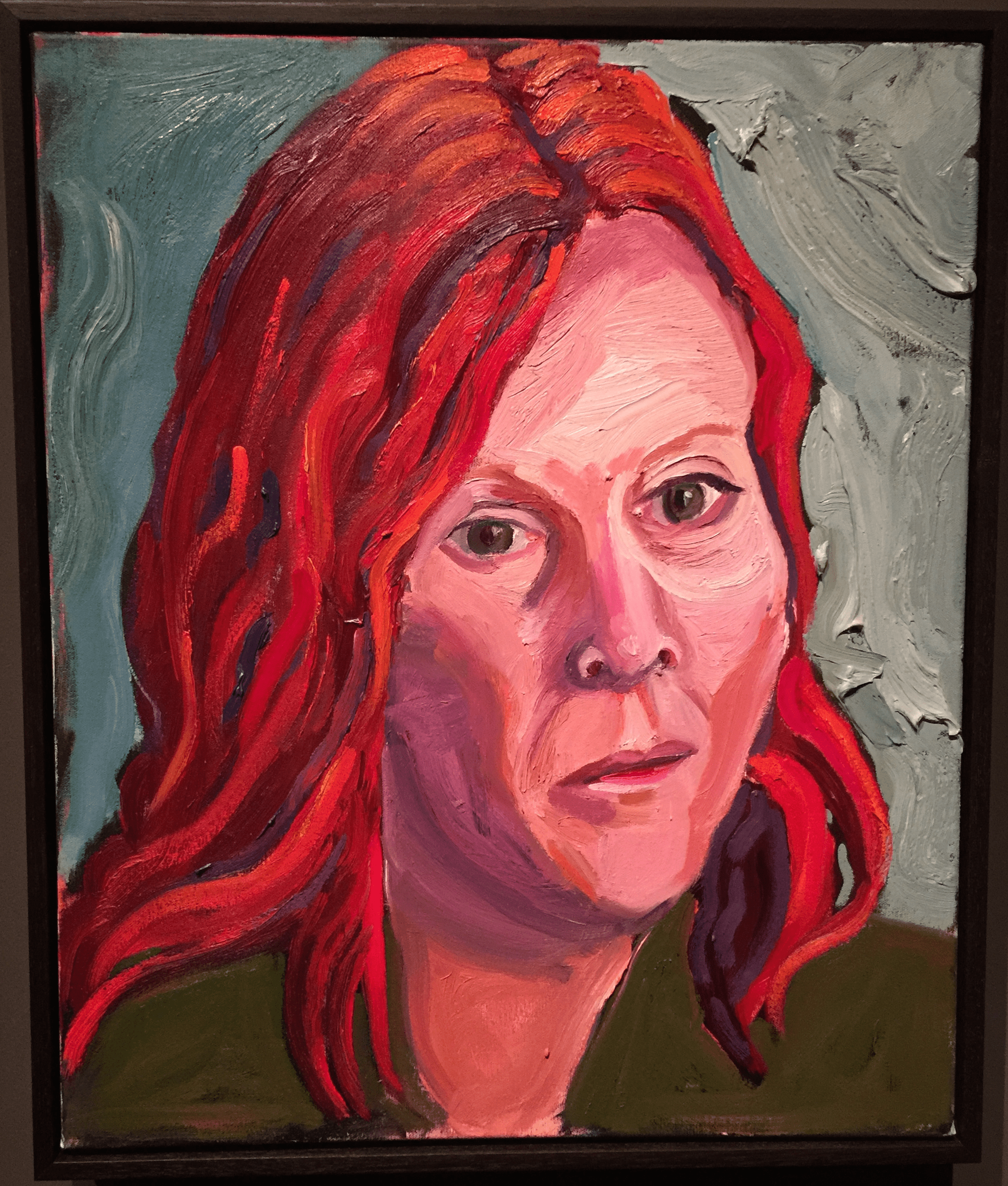

There seems to be some cultural representation within the portrait series, including the depiction of at least one immigrant who gained citizenship through military service, but the gender discrepancy is striking. The exhibition contains only two portraits of women. Sergeant Leslie Zimmerman’s portrait is bust-length and smaller in scale at twenty by twenty-four inches, while First Lieutenant Melissa Stockwell’s is full-length at thirty-six by forty-eight inches. Zimmerman has prominent red hair, the waves of which echo in the pale green background of the portrait; her cheeks are somewhat sunken, her mouth inscrutable; and her eyes gaze out toward the right of the viewer. I contacted Zimmerman about her portrait, and she replied that its source photograph was a still shot from a video created by the Bush Center.1

In this case, the photograph represents a single moment from a time-based work. In his anecdote on Zimmerman in the catalogue, Bush reveals that she was diagnosed with PTS and depression following her deployment. She comes across as much more confident in the video than in her portrait, which shows her as tough but distant, and perhaps not fully self-assured. The portrait focuses on the contrasts between the brightness and waviness of her hair and the paleness of her skin and leanness of her cheeks. Her injury is an invisible one.

The portrait of Stockwell, by contrast, shows a physical injury. It is the only one in the exhibition accompanied by its source photograph, encased with a letter from Stockwell to Bush. Inexplicably, the photograph is in a different room than the painting, making thoughtful in-person comparison difficult. The painting, however, is charming. It stands out because it also includes the artist’s self-portrait: Bush on the right dancing with Stockwell on the left. They both have bright smiles and while Bush is dressed in dark clothing—he didn’t seem to want to deal with the plaid pattern of his shirt in the photograph—Stockwell wears a light gray dress with a bright red belt and red shoes. Her weight-bearing right leg in the foreground is muscular, which Bush emphasizes with long tonal highlights. The left leg is a prosthesis wrapped in red, white, and blue. As the docent told me, “He didn’t paint it very well, but that’s an American flag.” The background of the painting is a murky army green, again full of built-up paint. The source photograph shows other people around them, and Bush’s catalogue entry on Stockwell indicates that they were dancing at a party after a bike ride in the Palo Duro Canyon (153). She seems like someone I would like to know. And yet, as with Zimmerman, I know nothing of her save for what filters into the catalogue entry and what I intuit from the portraits.

To get some perspective on the portraits from the point of view of a veteran turned artist, I spoke to Sergeant Phillip John Romero, a student in my university department who served two tours in Iraq. Romero felt that the series was a student assignment worked out on a massive scale and that the president did not seem to linger very long on the pain of each subject. Romero also argued that the exhibition was intended for civilian viewers. He articulated this from his own perspective as a soldier: “This exhibition is like looking at different versions of yourself, and you don’t want to see yourself.”

Bush has granted relatively few interviews related to the exhibition, but one of the most telling is his discussion with Aaron Gell of Task & Purpose, an online magazine for veterans. Asked whether he considers his painting a form of therapy, Bush replied, “In a sense, it is therapeutic. Not that it unburdens my soul. It’s not the painting that unburdens my soul. It’s the belief in the cause and the people—to the extent that a soul needs to be unburdened.”2 Then, when asked further if he himself had experienced PTSD, Bush responded, “Not even close. Did I feel grief as the person responsible for them being there? Yeah, I felt it, because others were grieving. And when others grieved, I grieved with them.” Bush’s characteristic garbling of words ostensibly echoes the internal conflict of sending people to war and whether the ends justify the means. The exhibition does not invite this questioning, but it clearly aims to humanize the war and highlight the president’s connections with the wounded. Bush would hardly be human if he did not feel the burden of grief in his position. Even if he does have serious regrets about his decisions, one hardly expects his presidential library to broadcast them.

In the New York Times, Mimi Swartz, a contributing writer covering Texas, writes, “Mr. Bush discovered what many who paint discover: that as he worked on their portraits, he came to understand the sitters, and their pain, as well as their love for one another.”3 But the subjects were not sitters. In his review of the exhibition that ran earlier that month, the New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl correctly asserts that Bush’s method of painting from photographs has a kind of “remoteness,” in that “[the] subjects aren’t present to the artist. They’re elsewhere.”4 Hyperallergic staff writer Seph Rodney, weighing in later that month, countered Swartz’s perceived softness toward Bush’s painting-as-therapy: “What’s insidious about the Times piece is that it puts readers in the position of feeling the need to forgive Bush and recognize his current art work as somehow redemptive.”5 What becomes problematic in this exchange is the assumption that Bush wants the public to forgive him. Bush wants the work to be seen as a tribute, and we want to see it as an apology. The paintings may be an apology for the fact that these men and women were injured, but there is no hint of regret or indecision as to whether the military should have been in Iraq or Afghanistan at all. A portrait is a poor apology for the horrors of war. A painting cannot make up for a lost limb, a traumatic brain injury, or persistent psychological trauma, no matter the prestige of the painter. Moreover, there are scores of other wounded soldiers who do not get valorized in portraits painted by the former president and who fight for proper medical care and dignity. Even if the viewer wants to see Bush’s paintings as portraits of psychological states, they are still filtered through the temperament of the artist.

A highly pressing concern regarding the exhibition is certainly the intention behind the works, and this may be an opinion formed before one enters the building. Rarely have viewers known (or think they have known) as much about an artist as they have in the case of a former United States president’s work presented for an audience willing to pay the nineteen-dollar admission fee to his Presidential Center. When considering intention and reception, one cannot ignore the fact that this is not a traditional art museum setting. The exhibition situates itself firmly within the political stance of the venue itself. It seemed that few of my fellow visitors cared at all about the fundamentals of technique or color or form in the portraits; what the images do is more important than how they look. And what they do is attempt to comfort the viewer. Does it matter that the artist is a self-proclaimed novice? In both the wall text and the catalogue, Bush repeatedly declares that these paintings are intended as a tribute to injured members of the Armed Forces, and that these veterans were wounded carrying out his orders as Commander in Chief. The title of Schjeldahl’s review referred to this series as Bush’s “painted atonements,” and there is certainly an element of sobriety to the exhibition. These portraits represent a power dynamic between a leader and his subordinates. Schjeldahl noted, “A leitmotif [of the catalogue] is the apparently terrific therapeutic value of joining Bush in his hobbies of mountain biking and golf.”6 In reality, few members of the Armed Forces get to breathe that rarified air.

This review would be much different had I written it a year ago. The course of the last presidential cycle in the United States has caused me to feel an unexpected nostalgia for “Dubya.” Though I did not vote for him and opposed many of his administration’s decisions, Bush has become somewhat precious in my memory. I like most of the paintings quite a bit, but I feel uneasy about the project as a whole—not for those portrayed in the paintings, but for those veterans seemingly left behind. As with Zimmerman and Stockwell, all I know of Bush is what I have been allowed to know.

Melissa Warak is Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of Texas at El Paso. She received her M.A. and Ph.D. in art history from the University of Texas at Austin. Her research focuses on the intersections of music, sound, and art after the 1950s.

- “Warrior Leslie Zimmerman,” at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=drBkScW8H90&feature=youtu.be., as of July 2, 2018. ↩

- Aaron Gell, “George W. Bush Opens Up About Veterans, Iraq, and the Healing Power of Art,” Task & Purpose, March 3, 2017, at http://taskandpurpose.com/art-war-george-w-bush-painting-patriotism-hacked-guccifer/, as of July 2, 2018. ↩

- Mimi Swartz, “W. and the Art of Redemption,” New York Times, March 21, 2017, at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/21/opinion/w-and-the-art-of-redemption.html, as of July 2, 2018. ↩

- Peter Schjeldahl, “George W. Bush’s Painted Atonements,” New Yorker, March 3, 2017, at https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/george-w-bushs-painted-atonements, as of July 2, 2018. ↩

- Seph Rodney, “George W. Bush’s Paintings Cannot Redeem Him,” Hyperallergic, March 28, 2017, at https://hyperallergic.com/368002/george-w-bushs-paintings-cannot-redeem-him/, as of July 2, 2018. ↩

- Schjeldahl. ↩