This is a parafictional story about a small American town and the frontier culture of manifest destiny.1 Palestine, TX is an intersection of colonial histories, of holy lands, of conjunctions and disjunctions, where the utopian location of Zion can always be found on the horizon and catastrophe is always underfoot. This project asks:

How do we claim a space as our own?

How do we occupy the spaces of others?

How do we navigate our way through zones of occupation?

How do we choreograph an occupier’s retreat?

In some ways, Palestine, TX charts the historical connections between the United States and Israel-Palestine. But more broadly, the project is concerned with global patterns of colonialism and the stakes of their representation. These patterns are often reinforced by tropes that become normalized and used by multiple sides of a given conflict. But is it possible for absurdist situations to be created that draw from these tropes and exaggerate their forms to the point that they start to seem unreliable? If so, could such situations destabilize these forms of representation and give us the opportunity to create new forms for not only representing politics, but conceiving of a given political reality?

During the First Intifada in 1987, camera crews filmed young Palestinians with keffiyeh wrapped around their heads as they threw stones at Israeli soldiers amidst the smoke of burning tires and clouds of teargas.2 The earliest images, now canonical, showed Israeli soldiers in full battle gear, countering with rifles and running past makeshift barricades in narrow city streets. These became emblematic of “the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.” Later, as media technologies expanded from television to social media, activists—without any claim to journalistic objectivity—edited these visual materials into YouTube clips that were then shared on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to illustrate ideological messages. These images have now become commonly redistributed by mainstream journalists, who use them to report on the situation on the ground. Changes in media platforms brought changes in our expectations about the relationship between images of current events and their instrumentality for overt political positioning. But despite changes in technology and even the political landscape, the same representations were reproduced again and again, looking almost identical to those early images from 1987. They were used by journalists, NGOs, politicians—many different actors with various political stakes. But the ur-image remained the same, whether it was shot in Nablus in 1987 or Gaza in 2018. From one point of view the Palestinian in this image was a freedom fighter. From another, they were a terrorist. The narratives surrounding the image were flattened out into two clichés, rooted in archaic forms of rhetoric, regardless of the advancing technologies for distribution. It is an image that could be seen as constructed, but even so, does its constructedness negate the broad range of truths of the political claims that it represents?

Parafiction subverts our assumptions and thereby short-circuits the feedback loops of inherited models of representation. It is a mechanism for making evident something that wasn’t visible before and revealing the facticity of the blind spot. With this strategy in mind, I created an exhibition in 2015 at the Reading Room in Dallas, a small nonprofit space dedicated to visual culture that intersects with language. The exhibition consisted of the timeline below and took the form of vinyl text and images fixed to the wall, as in a small historical museum. A central component of the project included two discursive programs—conversations with local artists and scholars who could speak to various dimensions of the project. For instance, a historian of the Middle East talked about the history of Israel-Palestine, comparing it to the Kurdish experience in Turkey; an art historian talked about representations of colonial Brazil; and a cultural worker with family from Palestine, Texas talked about the importance of Zion to the African American imaginary from the civil rights era through today. Palestine, TX was reimagined for Art Journal Open to allow for more subtext—a series of interrelated histories that function like an annotated bibliography for the original project. It also begins with a timeline, a structure for relaying history that has a number of narratives embedded within it. This timeline includes hyperlinks that, should one choose to follow them, will guide the reader to their related narratives. One could read through the various components of this text from start to finish, or read the related texts while jumping back and forth from the central timeline.

Palestine, TX is predicated on the notion that if we want to change politics, we must change representation. Images like the one that I describe above locate the politics of Israel-Palestine elsewhere for American audiences. But Palestine exists right here at home. An oft-cited statistic is that the United States gives $3 billion in military aid to Israel each year. But the relationship between the many entities involved in this situation is much more complex, and goes much deeper. It includes Christian Zionism, from its Puritan roots in the seventeenth century to the heights of its political influence during the George W. Bush and Donald Trump administrations; histories of African American groups like Black Lives Matter, which sent a delegation from Ferguson, MO to Bethlehem in solidarity with the Palestinian struggle; and the crucial role that Israeli technology plays in the militarization of the US-Mexico border. Finally, Palestine, TX challenges us to recognize parallels between the indigenous histories of the Middle East, the Americas, and the parafictional locality of Palestine, Texas.

What is the utility of parafiction to address contested politics in an age of “fake news”? On the one hand, a project like this seems to fall into the same traps as the rhetoric that questions the possibility of fact and reduces everything to opinion. But when we consider the ways in which representation functions in relation to the politics of Israel-Palestine, we see that the truth of an image has been at issue for some time. I was once told that during the First Intifada, international television news crews would film protests, and when they left, sometimes the protesters would also leave, as if everyone involved—Palestinian protesters, Israeli soldiers, and the journalists filming them—were all aware of their roles in political theater. Does this undo the authenticity of their protest or the anger and frustration that fueled it? Or does it reflect a self-awareness of the performativity of protest and its use in changing global opinion about the conditions of occupation?

- I use the term “parafiction” in the sense that Carrie Lambert Beatty does. She says, “in parafiction real and/or imaginary personages and stories intersect in the world as it is being lived.” See Carrie Lambert-Beatty, “Make Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility,” October 129 (Summer 2009): 54.

- The First Intifada, meaning “uprising” in Arabic, was a Palestinian revolt against Israeli occupation that lasted from 1987 to 1991.

The Story of Palestine, Texas

1678

French explorer Jean Lamotte discovered the territory now known as Palestine, Texas. Upon clearing a ridge and gazing down onto a beautiful valley with a sparkling river of crystal clear water, he claimed that it reminded him of the Holy Land, with milk and honey, as promised in the scriptures. Lamotte noted the location of Palestine in a map that he drew in his journal, and returned east.

1776

Thomas Paine published his pamphlet Common Sense, in which he argued, “We have every opportunity and every encouragement before us, to form the noblest, purest constitution on the face of the earth. We have it in our power to begin the world over again.” Paine believed that the first world began with the Garden of Eden in biblical Palestine and that the New World would usher forth from a Palestine found in America. [A Match Made in Heaven]

1787

At the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, George Washington whispered to John Adams that he had seen Lamotte’s journals and that once America had established independence, he would send a group of settlers to the site Lamotte had marked as Palestine. Washington believed that this would anchor America as the God-given Promised Land—a new Israel. Washington never was able to reach this goal, but he wrote a secret letter to all future presidents urging them to find the Palestine within America, based on Lamotte’s maps.

1823

During his State of the Union Address, President James Monroe laid out what would later become formally known as The Monroe Doctrine, declaring the United States of America as the New World that would take over the colonial expansion of the European Old World.

1830

President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which legalized the forced dispossession of Native American tribes. [Indigenous Histories]

1845

John O’Sullivan wrote an article about Manifest Destiny, the notion that Americans are morally superior and obligated to uplift less civilized societies such as Native Americans and Mexicans. O’Sullivan also argued for American expansion and advocated for the annexation of Texas.

1846

President James Polk was inspired by O’Sullivan’s article and the recent annexation of the Republic of Texas by the United States. He acted on Washington’s letter and sent Daniel Parker to Texas along with a group of settlers, who found the site as described in Lamotte’s journals. Parker’s settlers built a small fort using a building method called “wall and tower.” [Settlement Architecture] This enabled them to quickly construct an encampment that could defend against the indigenous tribes that lived in the region. Parker called this new township Palestine, Texas.

1847

President Polk sent Jewish families to help settle Palestine. Polk believed that Jewish people had ancient knowledge of Palestine and would know how to establish it in the New World.

1848

The settler community of Palestine began to grow and fighting soon broke out between this community—backed by the US Army—and the Comanche, Tonkawan, and Apache tribes. These battles became known as the 1848 War. Palestinians would invade native villages and drove most of the local population out. Palestinians won this war and relegated the remaining Native Americans to refugee camps, giving them American citizenship, but with limited rights.

1880

By 1880, Palestine had become a prosperous railroad community and the heart of American expansion, pumping people from the east to the west. The Jewish community of Palestine, including the Epstein, Davidson, Jacobs, and Kohn families, had become central to the town and its social order. Upon visiting the town in 1879, newspaper editor Charles Wessolowsky noted that Jewish residents were so satisfied in their current environment that they omitted the traditional recitation of “next year in Jerusalem” from the Passover Haggadah.

1922

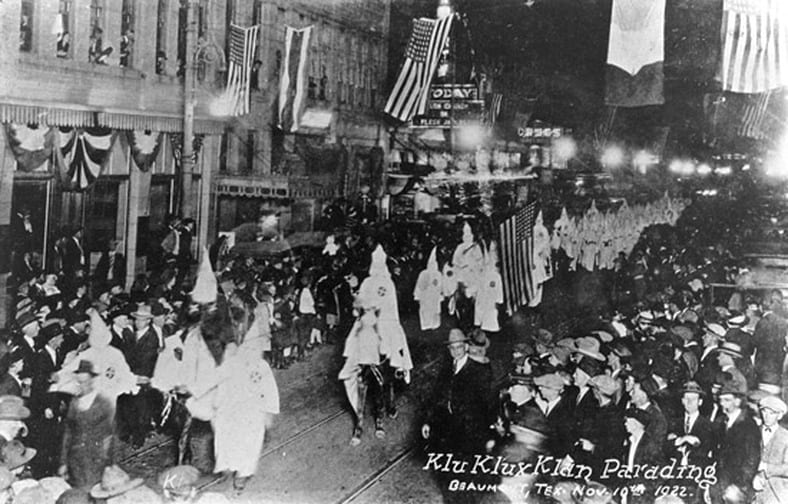

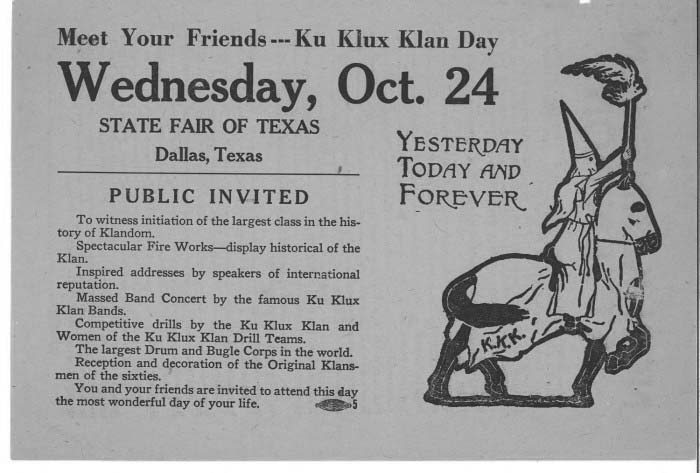

Formed in 1824 as an office of the US government, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) managed Native Americans through a policy of assimilation. In the early 1920s the BIA, whose regional headquarters were in Palestine, became increasingly influenced by the powerful Ku Klux Klan (KKK), moving beyond policies that sought to eradicate native cultures toward a more general policy of white supremacy. [From Ferguson to Palestine] The BIA became hostile toward the local Jewish population and bullied them into either leaving town or moving into the refugee camps with the Indians. With the resurgence of the KKK in the 1920s, the group’s fear and hatred of African Americans expanded to Jews, immigrants, and anyone that strayed from their racist vision of a white America.

1948

By 1948, the refugee camps were encircled by high cement walls. [Gaza in Arizona] It was ruled that “Native Americans and Jews that wanted to work in Palestine would have to get travel documents” and stand in line for hours at checkpoints into the city. These conditions exist to the present day. Native tribes dream of returning to the valley of sparkling clear water, and Jews have reinserted the excised passage of the Haggadah saying now each Passover—next year in Jerusalem.

A Match Made in Heaven

The history of Christian Zionism is the history of a set of linkages between America and historic Palestine. One key conjunction is the notion of America as Zion, a utopian home for a persecuted people. Another is that both America and the State of Israel have built a national identity on exceptionalism.

In 1630, the Puritan John Winthrop preached, from the deck of a ship that sailed from England to the New World, that their new colony would be a “city upon a hill”—a shining example to the world. This ship was carrying a group of refugees fleeing the religious persecution of King Charles I. They identified with the ancient Israelites’ suffering and compared their tyrannical king to the Egyptian Pharaoh who pursued Moses.1

The phrase that Winthrop used quotes Matthew 5:14, in which Jesus tells those gathered to listen to his sermon on the mount: “You are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden.” It has distinct parallels to the phrase in Deuteronomy 14:2 that is often used to describe the chosenness of the Jewish people: “For you are a holy people to your God, and God has chosen you to be his treasured people from all the nations that are on the face of the earth.”

In 1776, Benjamin Franklin proposed a seal for the United States. It depicts the Israelites being chased through a parted Red Sea by Pharaoh, who threateningly brandishes his sword. Moses, with the Jewish people behind him, stands on the shore and gestures towards the gathering Egyptian hordes so that the sea will overwhelm them. Above this scene is a fiery pillar, signifying the ferocious blessing of God’s power that lights the way for this ragtag group of refugees as they flee Egypt towards the promised land. Surrounding the seal is the phrase: “Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God.”

The American phenomenon of Christian Zionism is a strain of Evangelical ideology that believes that the state of Israel is the product of biblical prophecy and that the Jewish people’s gathering in the land of Israel is a precondition for Christ’s Second Coming. While American Christian Zionism had strong Puritan roots sustained through the nineteenth century, it wasn’t until after World War I that American Christian Zionism began to gain momentum alongside the growing political power of Evangelical Protestantism. In 1932, the Pro-Palestine Federation of America was founded by Christian leaders in Chicago. Then in 1948, when the State of Israel was established, American Christian Zionists saw it as a sign from God. The power of the Christian Right grew in the wake of World War II, as the Cold War was increasingly seen as a battle between good and evil. Evangelical leaders such as Carl McIntire, creator of the American Council of Christian Churches (ACCC), and Billy Graham emerged during this post-war era.2 In 1967, when Israel occupied East Jerusalem, Evangelical leaders argued that it was not only a further sign from God that the Jewish people were receiving the bounty of a divine promise, but also that the Jewish State should be an ally against Communism.3

The gestures of friendship between Israel and Evangelicals in the United States went both ways. In the 1950s, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion met with W.A. Criswell, pastor of the First Baptist Church of Dallas. In 1959, Ben-Gurion received Oral Roberts, and in 1961 he pushed for the World Conference of Pentecostal Churches to be held in Jerusalem.4 In the 1960s and 1970s, Israel shifted from a secular socialist form of Zionism to a more privatized one, and moved closer to the socioeconomic policies of the United States.5 Menachem Begin’s election to Prime Minister of Israel in 1977 signaled not only a more capitalist set of economic policies, but also the rise of the religious right in Israel. Jerry Falwell played a pivotal role in helping build US support for Israeli policies. When President Clinton summoned Benjamin Netanyahu to Washington, DC in 1998, Falwell, with Voices United for Israel, arranged for 1,500 evangelicals to welcome Netanyahu at the Mayflower Hotel. Falwell also promised Netanyahu that he would mobilize 200,000 pastors to preach to their congregations against the principle of Israel handing over any portion of the West Bank to the Palestinians.6

The attacks of September 11, 2001 marked a huge acceleration of the influence of Christian Zionists on US-Israeli policy. In a speech on the Senate floor, Senator James Inhofe (R-OK) likened the narratives of the United States and Israel, arguing that they struggle against the same enemy.7 This image of Americans and Israelites jointly under threat by a nefarious Middle Eastern tyrant invokes the Benjamin Franklin’s seal. Osama Bin Laden, Saddam Hussein, Hassan Nasrallah, or Khaled Mashal all became conflated as the dreaded figureheads of Islamic extremism that both the US and Israel must combat in a theological struggle.

Christians United for Israel became a political force in this context. Founded in 1992, it gained prominence with the leadership of the Reverend John Hagee, who runs the Cornerstone Church in San Antonio, Texas. Hagee has turned Christians United for Israel (CUFI) into a powerful political force that boasts a constituency of three million Christians who support Israeli policies. Its annual Washington summit has included speakers such as Vice President Mike Pence, Senator Joseph Lieberman, Senator John Cornyn, Israeli Ambassador Ron Dermer, and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

There are overlapping sensibilities of Christian and Jewish Zionism at the service of two nations, America and Israel. Both nations believe in self-determination and divine right, but the mythologies of both nations as oppressed groups of righteous insurgents against tyranny is an inversion of the real power structures at play. Both American and Israeli histories share the narrative of the pilgrim and the pioneer, but also, the less-often-acknowledged histories of colonialism, settlement, and domination over an indigenous population. Christian Zionism is more than just a metaphor concerning two nations. From the perspective of John Hagee and others like him, it is the story of a match made in heaven: two nations that not only share similar histories, values, and strategic goals, but that have also been chosen by God to work together against the forces of tyranny.

- Victoria Clark, Allies for Armageddon: The Rise of Christian Zionism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 39.

- Donald Lewis, The Origins of Christian Zionism: Lord Shaftesbury and Evangelical Support for a Jewish Homeland (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- Clifford A. Kiracofe, Dark Crusade: Christian Zionism and US Foreign Policy (London and New York: IB Tauris, 2009), 100–122.

- Stephen Spector, Evangelicals and Israel: The Story of American Christian Zionism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 144.

- The Israeli Pavilion at the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennial presented a study of this shift, looking at the growing influence of the US in Israel in the 1970s, which was tied to a process of Israeli privatization. The title of the exhibition, Aircraft Carrier, alluded to US Secretary of State Alexander Haig’s humorous observation that Israel since the 1970s was “the largest American aircraft carrier in the world,” implying that the shifts in economic policy and diplomatic alliances were tied to US cold war strategy. See Milana Gitzin-Adiram, Erez Ella, Dan Handel, eds., Aircraft Carrier: American Ideas and Israeli Architectures after 1973 (Berlin and Stuttgart: Hatje Cantz, 2012).

- Spector, Evangelicals and Israel, 148.

- Robert O. Smith, More Desired than Our Own Salvation: The Roots of Christian Zionism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 7.

Indigenous Histories

Steven Salaita has suggested that a comparison of Native American and Palestinian dispossession might be useful if we consider them related forms of settler colonialism. But the two histories diverge temporally: the disinheritance and dispossession of Native American and Palestinian populations began over a hundred years apart from one another. For Palestinians who embrace the right of return, there is still hope, albeit dim, that the Israeli occupation will end; among the first generation to experienced a pre-1948 Palestine, some are still alive. Native American populations, on the other hand, were dispossessed beginning in the late eighteenth century, before the 1830 Indian Removal Act was signed.

But Salaita cautions us from subscribing fully to this comparison because it implies an erasure of contemporary Native American identity and agency. Salaita points out that hundreds of Native American nations continue to fight for treaty rights and other forms of self-determination. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) issues its own passports, and there are ongoing efforts across the United States to preserve various aspects of Native American culture, such as ceremonial practices and language. But this is within the context of continued colonization, as in the highly publicized case of the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline in Standing Rock.

Settlement Architecture

Between 1936 and 1939 in Palestine there was a period of Arab revolt against both mass Jewish immigration and the British mandate. This triggered the Jewish European settlers to embark on an operation declaring a new territorial reality through the expansion of Jewish settlements in Palestine. Through well-planned and quick operations, more than 57 settlements were constructed, many of which were built overnight.

The method of construction was called “wall and tower,” first invented by the members of kibbutz Tel-Amal. The goal was to build on land purchased by the Jewish National Fund. The system involved building a wall made of prefabricated wooden molds made of gravel and surrounded by a barbed wire fence. The resulting space was about 35 by 35 meters. Within this enclosure, a tower and four shacks were built.

According to the architect Sharon Rotbard, this system might seem defensive, but it is actually offensive. Following 1948, the Israeli army embraced settlement as one of its main missions. Prime Minister Ben Gurion created a special unit that combined military activities and architectural settlement. He said in a speech to the first of these units that victory is achieved “not with silent stone fortifications but with labor and creation of a living human wall, the only wall able to resist the enemy’s weaponry. The only sustainable occupation resides in building.”1

- Sharon Rotbard, “Wall and Tower (Homa Umigdal): The Mold of Israeli Architecture” in A Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture, ed. Rafi Segal and Eyal Weizman (London: Verso, 2003), 39–56.

From Ferguson to Palestine

The Ku Klux Klan has historically targeted both African Americans and Jewish Americans. On the one hand, this has produced solidarity between African American and Jewish American groups. On the other, there have also been some great divides, especially when it comes to Zionism versus Palestinian solidarity. This is further complicated by the problematic equation between antisemitism and anti-Zionism.

Following the unrest in Ferguson, Missouri in the summer of 2014, some noticed that the images of protesters in Ferguson and the militarized police response were strikingly similar to images that have been common in the West Bank and Gaza since the first Intifada in 1987. Angela Davis has written about the connections between Ferguson and Palestine and, like many activists, has compared the Israeli occupation of Palestine to apartheid-era South Africa. The term “apartheid” was also included in the Movement for Black Lives’ political platform, as well as in support of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement (BDS), but this kind of Palestinian solidarity has been met with some backlash.

The negative reaction toward African American and Palestinian solidarity shared by some parts of the Jewish community reveals a complex history between Jewish and African Americans. Jewish Freedom Riders participated in the civil rights struggle and rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marched with Dr. King. The KKK believed Jews were just as much of a scourge as black people—a notion that the neo-Nazi marchers in Charlottesville in the summer of 2017 reinforced by shouting “Jews will not replace us.”

In recent years there has been increasingly visible African American/Palestinian solidarity work. In 2015 a delegation of black journalists, artists, and organizers representing Ferguson, Black Lives Matter, Black Youth Project 100, and the Dream Defenders traveled to Palestine for a ten-day trip. The trip followed a year of protests in Ferguson, Missouri in the wake of the fatal shooting of Michael Brown by white police officer Darren Wilson. In the highly publicized protests in the summer of 2014, Palestinians tweeted advice about dealing with tear gas. These messages included: “Always make sure to run against the wind / to keep calm when you’re teargassed, the pain will pass, don’t rub your eyes!” and “Made in USA teargas canister was shot at us a few days ago in #Palestine by Israel, now they are used in #Ferguson.”

In 2015 a short video, “When I See Them I See Us,” was released by a range of African American and Palestinian solidarity groups, and included such celebrities as Lauryn Hill, Cornel West, Alice Walker, and Danny Glover. Noura Erekat, a Palestinian-American legal scholar and human rights attorney, was inspired to produce this video in the summer of 2014, during which Israel and Gaza were engaged in an armed conflict that resulted in the deaths of 2,200 Palestinians. This coincided with the 2014 protests in Ferguson, and Erekat was interested in the parallels of dehumanization and criminalization.

Gaza in Arizona

The wall that separates Israel and the West Bank has been very influential on US border security. As the US–Mexico border has become increasingly militarized since the September 11 terrorist attacks, and even more so since the election of Donald Trump, Israeli technology has played a crucial role. In the decade following 9/11, sales of Israeli security technology rose from $2 billion to $7 billion annually. A major player in this has been Elbit Systems, a privately owned military manufacturer based in Israel. In 2004, Elbit’s Hermes drones were the first unmanned aerial vehicles to patrol the southern border of the United States. In 2014, Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) agency in charge of policing our borders, contracted with Elbit Systems to build a “virtual wall,” a technological barrier set back from the actual international divide in the Arizona desert.

An article in Salon quotes Roei Elkabetz, a brigadier general for the Israel Defense Forces, saying to an audience, “We have learned lots from Gaza. …It’s a great laboratory.” That same article also cites a 2014 presentation in El Paso, Texas that Elkabetz gave about surveillance balloons with high-powered cameras, seismic sensor systems, and “smart fences,” highly fortified steel barriers that have the ability to sense a person’s touch or movement. The Golan Group, another Israeli consulting company, has provided courses for special DHS immigration agents. Another Israeli company, NICE Systems, worked with former Arizona sheriff Joe Arpaio to aid in surveillance systems.

The United States’ contemporary political discourse is consumed with debates about refugees, immigration, and stateless people, and the borderlands of the south have become the locus of contestations around sovereignty and rights. Israel has been able to develop exporting technologies precisely because it has been administering stateless Palestinians since 1948.

Figure Captions

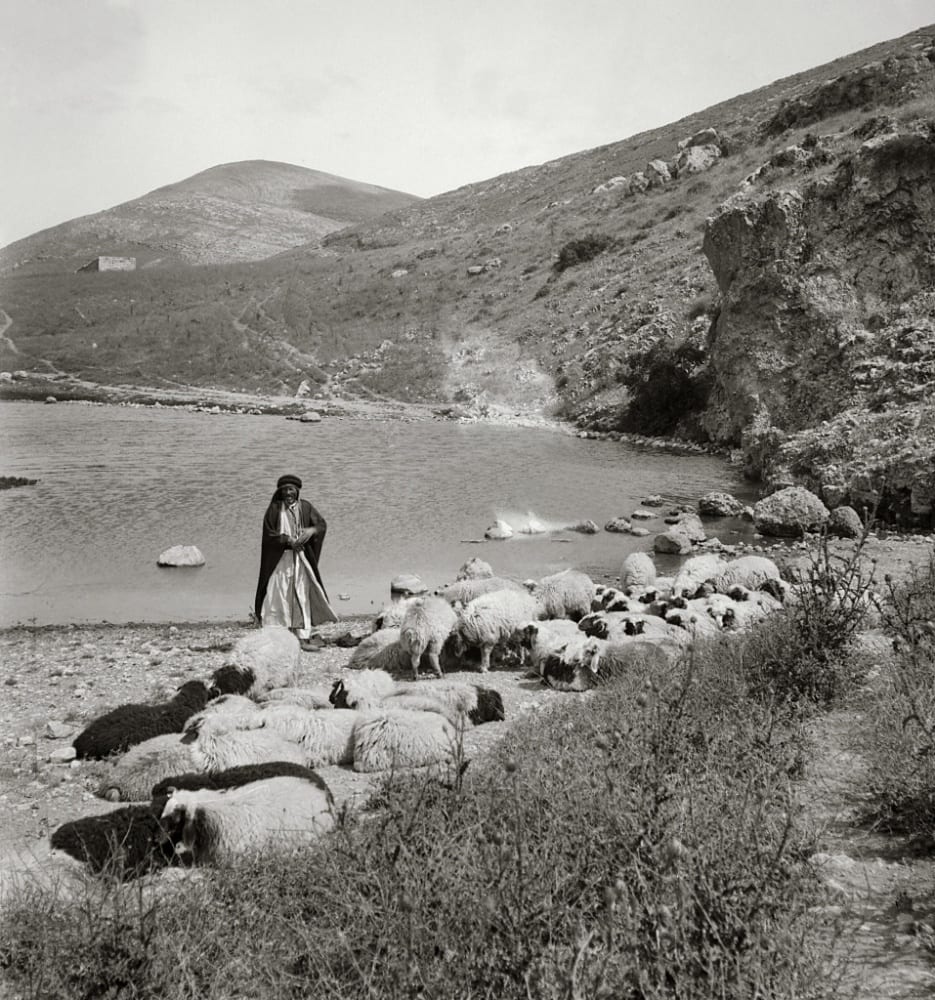

- Eric Matson, Ein Haron, Gideon’s Fountain, photograph, courtesy the American Colony in Jerusalem Photography Archive.

- Noah Simblist, Jerusalem, 2014, photograph.

- Eric Matson, Sychar and Mount Gerizim, photograph, courtesy the American Colony in Jerusalem Photography Archive.

- John Gast, American Progress, 1872, oil on canvas. Artwork in the public domain.

- Eric Matson, Ein Gev Lookout Tower, photograph, courtesy the American Colony in Jerusalem Photography Archive.

- Noah Simblist, Beth Israel Cemetery, Palestine, TX, 2015, photograph.

- Noah Simblist, West Bank Wall, 2008, photograph.

- Noah Simblist, Beth Israel Cemetery, Palestine, TX, 2015, photograph.

- Ku Klux Klan parading in Beaumont, Texas, 1922, photograph, courtesy Patricia Bernstein.

- Flier advertising “Klan Day” at Fair Park, Dallas, Texas, October 24, 1923, photograph, courtesy University of North Texas Libraries.

- Noah Simblist, Checkpoint in Bethlehem, 2008, photograph.

- Noah Simblist, Graffiti on Wall in Bethlehem, 2008, photograph.

Noah Simblist works as a curator, writer, and artist with a focus on art and politics, specifically the ways in which contemporary artists address history. He has contributed to Art in America, Modern Painters, Terremoto, and other publications. He is editing a book, to be published by the University of Chicago Press, about Tania Bruguera’s The Francis Effect, a project coproduced by the Guggenheim Museum, the Santa Monica Museum of Art (now ICA LA), and SMU. Curatorial projects include Emergency Measures at the Power Station in Dallas, Queer State(s) at the Visual Arts Center in Austin, and False Flags with Pelican Bomb in New Orleans. In 2016, he was the cocurator and coproducer for New Cities Future Ruins, a convening that invited artists, designers, and thinkers to reimagine and engage the extreme urbanism of America’s Western Sun Belt. His most recent projects include Reading Monuments, a series of reading groups in four southern cities to interrogate the legacy of Confederate monuments, and Commonwealth, a multiyear project exploring the notion of the commons at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University. He is also Chair of Painting + Printmaking and Associate Professor of Art at VCU.