From Art Journal 79, no. 4 (Winter 2020)

member: Pope.L, 1978–2001. Exhibition organized by Stuart Comer with Danielle A. Jackson. Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 21, 2019–February 1, 2020

Pope.L: Choir. Exhibition organized by Christopher Y. Lew with Ambika Trasi. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, October 10, 2019–March 8, 2020

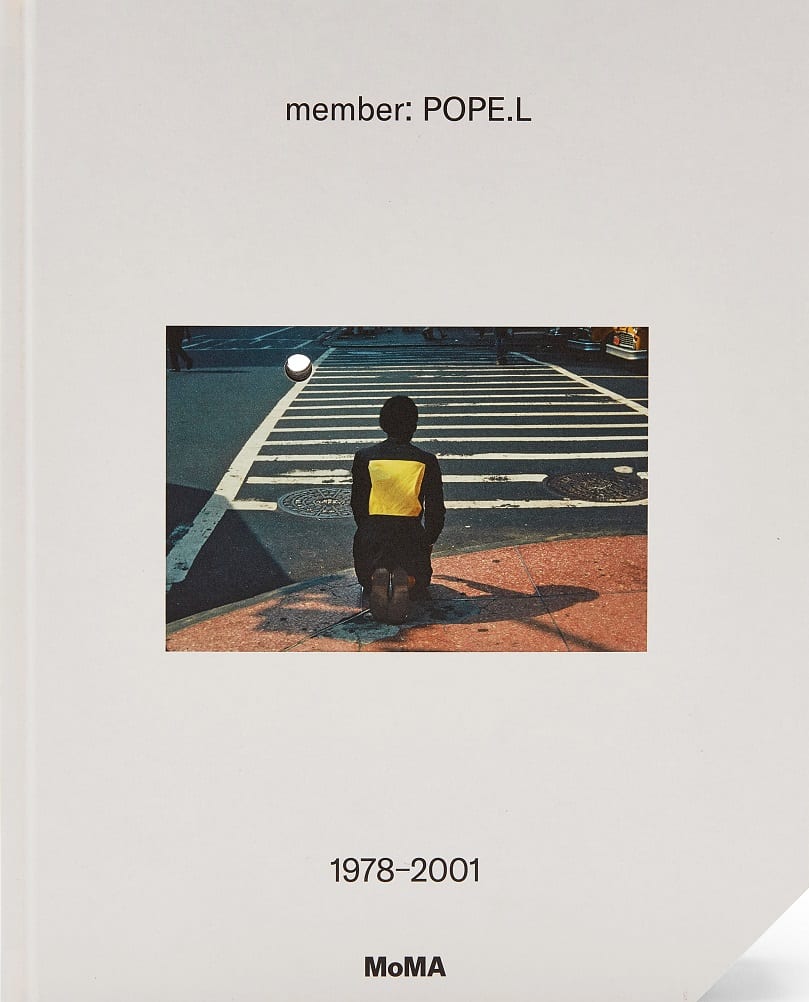

Stuart Comer, ed. member: Pope.L, 1978–2001 . Exh. cat. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2019. 144 pp.; 100 color ills. $40

At the entrance to member: Pope.L, 1978–2001, at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, the visitor was immediately introduced to two lines of inquiry that have dominated Pope.L’s career—the body and the void, or, in the artist’s words, the state of “have-not-ness” (21). A photograph from the artist’s Times Square Crawl a.k.a. Meditation Square Piece (1978), reproduced larger than life and installed on the entrance wall, was punctured by a square hole, which allowed a glimpse of the next gallery and the floating heads of other museumgoers. This element of the hole recurred throughout the exhibition in various forms and is incorporated into the design of the accompanying catalog. There is a circular hole, slightly smaller than the diameter of a regular pencil, that goes through the entirety of the book. The lower right corner of the publication is also missing, cut cleanly at a forty-five-degree angle. Pope.L (b. 1955, New Jersey) has written extensively on the nature of holes, at times referring to them as tunnels, a means through which to arrive at something else, like a mode of transport or transition. He explains that holes “by their very nature only reveal a part of themselves” and that often the viewer (or the reader, in the case of the catalog) is left to fill in what is missing (33).

Such disruptions signaled an intervention into what at first glance appeared to be a historical survey, a look at the artist’s early work prior to his major 2002–4 traveling exhibition organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art at Maine College of Art, DiverseWorks Artspace, Houston, and Portland Institute for Contemporary Art, Oregon. Upon entering the first of two gallery spaces, the viewer encountered additional elements that denoted interference with a relatively traditional display of various objects—costumes, scripts, props—associated with the archiving of performance. Small—almost so small they could be missed—pencil marks, doodles, and writings had been added to the otherwise pristine, white gallery walls. They referenced current politics, engaged in dialogue, commented on works on view, and seemed to chide the exhibition itself. Additionally, works of art outside the 1978–2001 time frame were hidden behind and inside walls or on high shelves in corners—Package Received but Never Opened #167 (2015), Failure Drawing #34: Chateau Hotel Bats and Piles (2004–6), and Package Received but Never Opened #21 (2017), for example—creating further disruptions to the visitor’s experience. Pope.L the consummate provocateur was at work, altering a space or situation in which coded experience is expected.

member was part of a trio of projects, collectively titled Pope.L: Instigation, Aspiration, Perspiration, that took place throughout New York City between September 2019 and March 2020 and that provided a broad perspective on the artist’s career, with a survey of early work, an installation, and a live performance. In addition to Pope.L: Choir at the Whitney Museum of American Art, discussed below, Public Art Fund presented in late September Conquest, a 1.5-mile group “Crawl” in downtown Manhattan, from the West Village’s John A. Seravalli Playground to Union Square via Washington Square Park’s triumphal arch. Over 140 volunteers participated in the Crawl, the name Pope.L has given to the slow, prone traverses through primarily urban spaces he began in 1978. To intensify the experience, each participant crawled with a blindfold and flashlight and with one shoe removed.

At MoMA, member was framed within the museum’s commitment to collecting, preserving, and presenting performance. Additionally, the project coincided with and celebrated the acquisition of more than 130 of Pope.L’s performance objects for the museum’s collection. Combined with the objects that constitute The Black Factory Archive (2004–), the acquisition ensures that the artist’s work is well archived at the institution. Stuart Comer’s “Introduction: A Lack in the Wake,” which orients the catalog reader to the exhibition, begins by characterizing Pope.L’s “multivalent work” as traversing categories, time, and space (21). Few of the artist’s biographical details are shared in the exhibition wall text or catalog, although some can be gleaned from the transcribed conversation between the artist, Comer, and Danielle A. Jackson (24–35). After graduate school at Rutgers University’s Mason Gross School of the Arts, Pope.L became immersed in experimental theater, and he worked with Mabou Mines before forming Tesla Linkum Theater Collective with Jessie Allen, Ledlie Borgerhoff, Jim Calder, Joe Daly, and Barbara Hiesiger. The artist explains that his 1991 residency at Franklin Furnace, and the support there from Martha Wilson, was another important experience, and he acknowledges the encouragement he received from his mentor, the Fluxus artist Geoffrey Hendricks. References to cultural and political events from the early 1990s—the inclusion of an antiobscenity restriction in an NEA appropriations bill and the violent beating of Rodney King by four Los Angeles police officers—pepper the catalog text, acknowledging the undercurrents of this significant decade in the artist’s career. The assembled voices of curators, scholars, and artists in the publication make for a rich inquiry into Pope.L’s diverse practice.

Pope.L’s performances can be loosely separated into those presented in a proscenium setting—for example, a stage in a designated theater or on a scaffold—and those that take place in accessible public spaces outdoors. member comprised thirteen works of art that fall within these two categories. Instead of a strictly chronological display, the works were installed between two galleries divided by a hallway installation of The Black Factory Archive. A darkened viewing room near the beginning of the exhibition screened a loop of five performance videos.

The earliest works in the exhibition, Thunderbird Immolation a.k.a. Meditation Square Piece (1978) and Times Square Crawl a.k.a. Meditation Square Piece (1978), demonstrate the artist’s early commitment to interventions in the public sphere. Times Square Crawl was Pope.L’s first Crawl, and the action was captured and presented through a series of photographs. We see the artist from behind, dressed in a business suit with a yellow square sewn onto his back, as he crawls on hands and knees through a section of West Forty-Second Street known then as the Deuce. By disorienting himself from vertical to horizontal and shifting our frame of vision to street level, Pope.L refocuses attention to the bodies that inhabit that realm. The artist interrupts our walk through the city and asks us to acknowledge his existence and by extension the vulnerability and value of homeless people. Germane here is the notion of kinesthetic empathy—feeling the experience of another’s body within our own. The photographs capture some of the responses—curiosity, confusion, averted eyes, and another intervention, that of a police officer—and the contemporary viewer is left wondering with whom empathy lies. In the accompanying catalog essay, Martine Syms reflects on the physical experience of Pope.L’s body in the street, and she discusses her own work as it relates to the physicality of existing in the body and the vulnerability of that position in relation to others.

Pope.L’s projects from the 1990s take a decidedly more overt presentational approach. The artist’s proscenium work from that decade—Egg Eating Contest (1990–91), The Aunt Jenny Chronicles (1990–91), and Eracism (1992–2002), for example—center on white perception of and racist projections onto the Black body. The performances incorporate the absurd, themes of gender, sexuality, and the family, and theatrical techniques such as the monologue and language play; the objects associated with the works—large drawings of cartoon phalluses, a tulle dress, and a bra—are reminders of that inhabited body. As with Pope.L’s larger practice, his stage work defies strict associations with either experimental theater or gallery-based performance. There is again a disruption into process and product, and Pope.L cites the “way of Fluxus” as influential—concurrently “inexpensive, indeterminate, open-ended, learned but stupid, fancy but poor, funny but sad, smart but down to earth” (30).

Back on the street, Pope.L is upright at times in the mid-1990s, as he probes and prods the public with protest-like action, as in ATM Piece (1997), or as he performs the wandering provocateur in Black Domestic a.k.a. Cow Commercial (1994) and Member a.k.a. Schlong Journey (1996). The last took place on 125th Street in Harlem. Wearing a suit and a backpack with a stuffed white bunny, Pope.L pushed ahead of himself a long, white cardboard phallus that protruded from his crotch and was supported by the base of a rolling office chair. It was a spectacle, as the artist intended, and the encounters ranged similarly to those of his Crawls but with the addition of an object for interaction. The great phallus, parting the space ahead of him with self-assured white supremacy, became interactive as Pope.L rolled raw eggs through the tube—another hole—or younger onlookers played around it. As Thomas J. Lax notes in his catalog contribution, “Pope.L’s White Stuff,” the equating of the white phallus (as well as the “big black dick”) with masculine creativity had been explored through artistic actions since the 1960s, as in Lynda Benglis’s 1974 Artforum advertisement (91). Now, more than twenty years later, the white schlong is still erect in the gallery, with its white bunny hanging flaccid from its end. Does the whitecube enclosure now surrounding the object, Lax asks, create a secure place for it among the “white phalluses of yore” (91) in MoMA?

Pope.L’s The Great White Way: 22 Miles, 9 Years, 1 Street (2001–9) is the most recent Crawl in the exhibition and an appropriate bookend to the survey, as focus is again shifted explicitly to the body. In the performance, the artist wore a Superman costume with a skateboard on his back in place of a cape. He then crawled—lower than in the late 1970s, belly against the ground—for the entire length of Broadway, from Liberty Island to the South Bronx, in segments over the course of nine years. The results of this physically taxing endeavor are visible in the ragged, dirty edges and missing knees of the costume, which was laid like the shell of a hero on its back directly on the gallery floor. When Pope.L became exhausted and the pain became unbearable, he rolled himself along on his back on the skateboard. These objects, along with photographs of The Great White Way and Training Crawl (for The Great White Way: 22 miles, 5 years, 1 street) and a 6.5-minute video of The Great White Way, document the artist’s longest Crawl. In his eloquent catalog essay “Making Way,” André Lepecki situates this Crawl within Pope.L’s continued exploration of the juxtaposition of body and void: “Crawling makes way for a mode of being whose full potentiality (plentitude) emerges only after going through the lived experience of existing in and as absolute lack (destitution)” (114; emphasis in original). As he is ordered back onto the ferry by two National Park Service troopers on Liberty Island, Pope.L points to what is and what is not available to the Black body.

At the Whitney, Choir was a new installation related to Pope.L’s projects about water. The darkened gallery off the museum’s lobby appeared disorderly—blue painter’s tape still stuck to walls and a sign, “DO NOT CLEAN SWEEP MOP THIS GALLERY,” taped to the glass doors. Bits of construction debris littered the floor, and on turning the corner at the end of the entrance corridor, the viewer was met by a large plastic storage container presented monument-like on a makeshift pedestal. The bright copper piping stood out in stark contrast to the darkened space, but the most present material was the water pouring from an old drinking fountain suspended upside down from the ceiling. As in an associated piece—Pope.L’s 2019 performance Flint Water Meets the Mighty Hudson, presented via video on the Whitney’s web page for Choir—the movement of the water appeared unceasing. The cyclical processing of the water was the potential end captured in the artist’s installation of clear, nearly full drinking glasses—collectively titled Well (Whitney Version) (2019)—installed in ten locations throughout the museum’s lobby and other galleries. The sounds of filling, draining, and refilling were simultaneously cacophonous and soothing, and behind the noise was an audio design by Matthew Sage in collaboration with Pope.L that incorporated 1930s gospel recordings. Black vinyl wall text referenced an anechoic chamber—a room meant to completely absorb sound—but when the water stopped abruptly, the viewer was left with a void filled by soft dripping and the gentle slapping of the water against the side of the tank.

Water in its various states is not a new topic in the history of art, but in Choir Pope.L makes the mechanics of the life-sustaining material visible. His 2017 Flint Water project addressed the public-health crisis that began in Flint, Michigan, in 2014, when water was diverted into aging pipes, causing lead contamination. In his accompanying essay, “Something from Nothing: On Pope.L’s Choir and Other Waters,” Christopher Y. Lew signals another association, the public water fountain and policing of it under white supremacist laws in the Jim Crow–era South. And this is to say nothing of the water bottle and its mechanics of distribution. As with Pope.L’s other projects that nudge the viewer toward contemplation of pervasive and biased systems, structures, and histories that cannot be changed, the mechanized distribution in Choir considers this politicized natural resource. Pope.L describes the installation as a “tumult space,” and in that disturbance and confusion, one can best hope to “merely survive and then to figure out the puzzle which is the work.”1

Back at MoMA, visitors could follow the artist’s holes, dots, ghosts, and tags through the exhibition to a black backpack emblazoned with “Pope.L” in red stitching. As the accompanying label explained, the presence of the backpack signaled the absence of the artist. Throughout member, Pope.L had been “haunting” the show, engaging with holes, his performances from the past, and museum visitors. The backpack hanging on its hook felt like another hole, or perhaps better a punctuation, referencing simultaneously the presence and absence of the artist—the body and its void.

Margaret Winslow is the curator of contemporary art at the Delaware Art Museum. Her recent exhibitions include Truth & Vision: 21st Century Realism (2016), Hank Willis Thomas’s Black Survival Guide, or How to Live through a Police Riot (2018), and Angela Fraleigh: Sound the Deep Waters (2019).

- Pope.L, email message to Christopher Y. Lew, August 2, 2019, quoted in Lew, “Something from Nothing: On Pope.L’s Choir and Other Waters,” Pope.L: Choir, Whitney Museum of American Art, April 29, 2020. ↩