Content Warning: This essay includes images and detailed descriptions of state and racialized violence and torture.

Since 2001, military “black sites,” or secret detention facilities, have been set up outside the United States in order to conduct “an alternative set of interrogation procedures on suspected terrorist leaders taken into custody.”1 When the Enhanced Interrogation Program (EIP) was first authorized by the George W. Bush administration, a multitude of techniques were used in these secret detention sites, such as suffocation by water, stress positions, beating and kicking, confinement in a box, forced nudity, sleep deprivation, and shackling. These techniques were aimed to break down the prisoner’s psyche, leading to delusions and hallucinations, mental clouding, confusion, and suggestibility, all of which the military contends helped better facilitate the gathering of intelligence.2 In creating the EIP, the military produced a self-aware, public acknowledgment of the brutalization considered necessary to combat terrorism, as well as a private inventory of how different techniques impact the captive.

Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn (Abu Zubaydah) was the first captive to undergo the Enhanced Interrogation Techniques and was infamously waterboarded eighty-three times in one month alone.3 Captured in Pakistan in 2002, Abu Zubaydah has never been officially charged with a crime and as of this writing in 2020 is still held at the detention camp housed in the US Naval Station at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Toward the end of 2019 the report “How America Tortures” was released. The report was compiled by Professor Mark P. Denbeaux of Seton Hall Law Center, who also serves as cocounsel to Abu Zubaydah and several other Guantánamo detainees. The report presents the specific details of the torture techniques used in the early years of the War on Terror and how exactly they were implemented on the body. Unique to the report is that in addition to the oral and written testimony compiled by Abu Zubaydah’s lawyers included throughout, it also comprises eight original drawings by Abu Zubaydah himself illustrating how techniques, such as water boarding, were administered repeatedly on him in a secret prison in Thailand in 2002.4 The drawings were prompted by Denbeaux, for release as evidence of the United States’ torture methods, and were completed by Abu Zubaydah at Guantánamo Bay in 2019.

Commenting on the drawings, journalist Carol Rosenberg makes the distinction between “artwork” and “legal material,” stating that Abu Zubaydah “drew these sketches not as artwork, whose release from Guantánamo is now forbidden, but as legal material that was reviewed and cleared—with one redaction—for inclusion in the study.”5 The denial of the drawings as artwork is both understandable and strategic, given the military’s decision in 2017 that any artwork made by captives at Guantánamo Bay belongs to the US government. Nonetheless, Abu Zubaydah’s drawings, as opposed to oral and written testimony, offer the opportunity to investigate a third mode of testimony, one more attuned to the visual and sonic dimensions of torture. Here I turn to several of Abu Zubaydah’s drawings included within “How America Tortures,” as well as a set of drawings that he completed years prior to the report. It is important to note that Abu Zubaydah had been actively drawing before submitting the images of torture for the report.6 These older sets of drawings are much less representational and engage with themes of torture but also time and his Palestinian identity. They were released in 2018 to ProPublica magazine in response to a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit. My presenting them here, then, is an exercise in listening to the sounds emanating from within the images, sounds that cannot necessarily be spoken. I approach Abu Zubaydah’s drawings as an opportunity to not only look at but to listen to the images of violence that he is offering the public. In listening to the images, I hope to make space for Abu Zubaydah’s drawings to function both as evidence and as a unique form of self-expression that conjures an aesthetic and auditory response in viewers.

By “listening,” I mean to invoke an approach to looking whereby one’s engagement with an image is predicated not solely upon sight but also upon the sounds that emerge from within images of pain and suffering.7 I maintain that confronting pain and its visual and sonic representations might provide us with an affective engagement that makes us capable of looking without reducing images of violence to spectacle or to the simple supplements typical of legal documentation of human rights abuses. The typical, utilitarian accounts of these drawings approach them within an ocular-dominant framework that resists a more affective engagement with the torture and/or pain and suffering that they depict. Such readings render the drawings as “mere evidence” of state torture; the more rational/didactic gaze lessens these drawings’ capacities to evidence something beyond how torture irreparably damages the bodyminds of victims.8

According to the report, there is something compelling about Abu Zubaydah’s visual representations in how they afford the viewer insight into the perspective of the tortured. The psychological character of prisoners has figured prominently in the sociocultural imaginary of the War on Terror.9 For example, in 2016 the New York Times did a special report on the mental health of men held captive at Guantánamo Bay. The article, “How U.S. Torture Left a Legacy of Damaged Minds,” offers important insights into life after Guantánamo Bay and how many of the men struggle with depression, anxiety and mood swings, and night terrors involving suffocation.10 Yet, so often the choice to use words such as “damaged” feels intensely diagnostic, and I wonder if there is another way to listen to what these men are trying to tell us.

Rather than reading Abu Zubaydah’s drawings and testimonials as representative of a “damaged mind,” I instead see them as an articulation of what it feels like to be exposed to the state’s management of life and death inside of confinement. And more, these drawings lend us a glimpse inside of Abu Zubaydah’s deeply imaginative inner life. His drawings facilitate a more robust visual grammar—one that refuses the state’s justification of torture as treatment on the racialized bodies held captive, pathologized as dangerous to both themselves and the larger public. Thus, the state’s logic relies on the intertwined discourses of both care and punishment, producing what disability studies scholar Liat Ben-Moshe terms “criminal pathologization,” or the construction of race (most often Blackness), disability, and mental differences as dangerous and in need of management and disposal.11

Abu Zubaydah’s images decenter the state’s point of view and center his own experience with trauma and debility inside confinement, while also evoking an aesthetic response in the viewer. There’s a visual literacy at play in Abu Zubaydah’s drawings, one that emerges out of visual culture rather than just from the events of having been tortured. In my reading, his drawings reference graphic novels and, in particular, comic book aesthetics in how he visually represents pain and sound as occurring, and how he figures himself registering the action happening to himself from the interrogator. Sound is also embedded through the textures of his line work. Thus Abu Zubaydah’s drawings, and by extension the aesthetic, moves beyond the verbal and instead orients the viewer to the various technologies of torture that are spatialized and sonic.

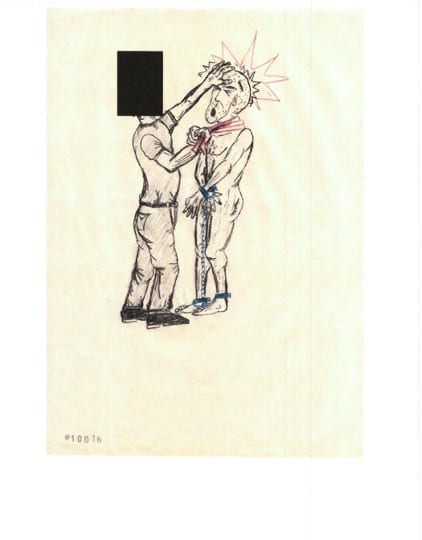

This first image (Fig. 1) depicts the technique of “walling,” showing the captor tightly winding a towel (drawn in red) around Abu Zubaydah’s neck as he smashes the back of his head against a cement wall. The “bam” sound of his head hitting the cement is represented in a red comic splash, and Abu Zubaydah’s eyes are tightly closed as his mouth gapes open. The face of the guard is redacted in the report, acting almost as an empty speech block, the kind one might also find in comics. In the accompanying testimony, Abu Zubaydah states:

They brutally dragged me to the cement wall. . . . He started banging my head and my back against the wall. I felt my back was breaking due to the intensity of the banging. He started slapping my face again and again, meanwhile he was yelling. He then pointed to a large black wooden box that looked like a wooden casket. He said: “from now on this is going to be your home . . .” He violently closed the door. I heard the sound of the lock. I found myself in total darkness.12

Methods of torture such as waterboarding and walling repeatedly attempt to break the body toward unspecified ends, in this case exposing Abu Zubaydah to death without actually killing him. Yet, he transforms the repetition of such violence enacted upon him into drawings that both stop time and demand that the viewer imagine the movement behind the still image and representation of torture. To look away too quickly is to risk comparing the pain of walling to mere “discombobulation,” the word one of the architects behind the Enhanced Interrogation Techniques used to describe this particular “enhanced interrogation method.”13 To look away too quickly is to refuse to listen to the world-shattering pain signaled by the spiky red lines ballooning behind Abu Zubaydah’s head,14 which work as a “sound image” of pain that may or may not be escaping his mouth as his head bangs back and forth.

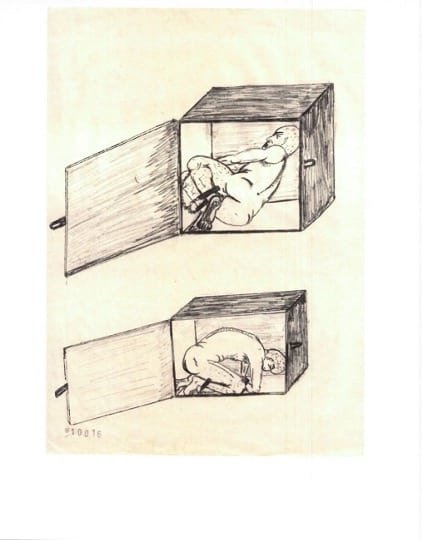

In Figure 2, Abu Zubaydah’s testimony moves us away from the ocular as he asks us to imagine—to listen with him to—the sounds that radiate between himself and the various technologies of torture (e.g., the wall, the lock on the wooden box). How does listening get us closer to the scene in ways that merely looking at the images cannot? What kinds of high-frequency sounds did he hear in total darkness, how long did his ears ring for? The drawing shows the box open, but eventually it would be closed, with Abu Zubaydah locked inside. With the denial of vision inside the box, sounds become heightened. There is much to be said about “sound torture,” the blasting of heavy metal music at captives for days at a time as a sleep deprivation tactic, for example. But Abu Zubaydah’s drawings for the report direct our attention to how silence and darkness also function as no-touch torture, and that like sensory overstimulation caused by the blasting of music, darkness and silence can also cause extreme forms of pain and disorientation.15 Abu Zubaydah’s drawings convert the moment his head hit the wall and the darkness he is left to face inside the box into complex aesthetic moments.

All of these drawings show an extreme attention to detail and the deploying of color in strategic ways so that the perspective highlights the specific objects used to administer the technique, such as the red towel around Abu Zubaydah’s neck or, in another image (not figured here), the blue restraint belts holding him down while he was being waterboarded. The confinement box, however, is more geometric and the lines more delicate, focused on how the body molds to the shape of the box itself. Abu Zubaydah’s face is contorted from the pain of being shackled for hours and the intense muscle contractions that inevitably ensue, illustrating for the viewer not only how the confinement box works but also the fear that arises once one is inside the box. Sound travels here in such a way that it is uncontained by the architecture of the prison, confinement box, or even the page. These are the sounds located between the oral testimony he gives to his lawyer and the sensual act of drawing. Drawing is sensual in that it is an embodied act between oneself and the page, a process that might bring reprieve to Abu Zubaydah, even as it takes place alone within the architectural echo of the prison and the lack of recognition between himself and the guards.16

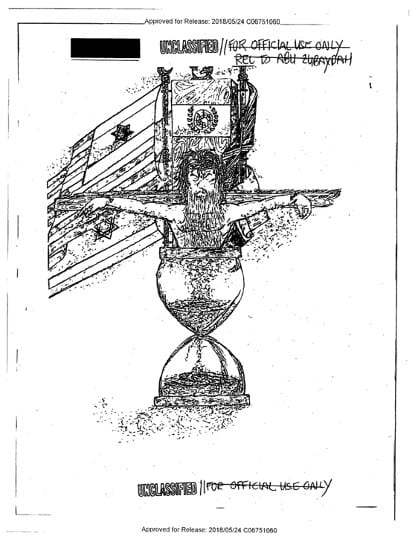

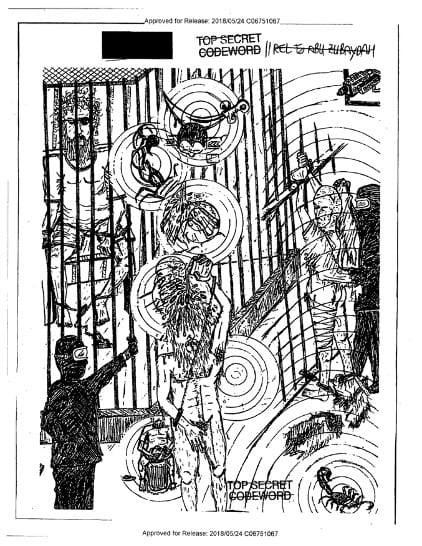

While the “How America Tortures” drawings deploy neutral tones such as beige and blue and are more naturalistic in style, the earlier drawings have a harsher hue and appear to be originally sketched in only black and white, thus reading as more graphic, abstract, and symbolic. There is a textured scratchiness embedded in the line work of these drawings. In Figure 3, we see Abu Zubaydah suspended from a flagpole from which the Israeli flag is waving. The pole also functions as a kind of cross, and although he is hanging from it, his lower body is shown disintegrating into a large hourglass. This drawing invokes, in particular, the figure of the martyr, or one who bears witness to their faith, a figure that occupies much of Palestinian visual and political culture.17 This image in particular also calls to mind Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali’s famous character Handala, a ten-year-old barefoot child in patched clothes.18 In most drawings Handala’s back is turned to the viewer and we rarely see his face. He is the witness and recorder of events, both an observer and a participant in the landscape that surrounds Palestinian refugees and resistance.

Similarly, it is not only the viewer who is a witness to torture but Abu Zubaydah, too, who in the act of drawing inhabits both the past and the present. Abu Zubaydah’s drawings of torture develop a visual language that is itself a form of storytelling that does something different than his written testimony. The drawings signal a deep alienation on the part of Abu Zubaydah; he is outside himself looking in. One might in fact read Abu Zubaydah as trapped inside his own images, though a more reparative reading might be that despite this abject relation to time and the body, he continues to make contact with an external reality through his drawings. And it is by way of the image that Abu Zubaydah helps us to see the relation between life, death, and time.

Time is a recurring symbol in these sets of drawings, suggesting that life’s tempo within confinement induces terror. The endurance of waiting to be released must be apprehended as its own kind of temporality, what Nicole R. Fleetwood names “penal time” in her work on carceral aesthetics.19 In this context normative mechanical time is irrelevant, with hours, days, and weeks merging together. Abu Zubaydah’s drawings make clear how time itself is used against the captive, and waiting is its own distinct experience of punishment. Although Abu Zubaydah’s drawings are much less caricatural than, say, al-Ali’s cartoons, they also are not photorealistic. Instead, they take on more of a comics-inspired shading or cross-hatching technique that renders what art historian Hillary L. Chute describes in the work of al-Ali as “a sophisticated yet accessible circulating form that brings attention to the witness . . . one recognizes the efficacy—the directness, the immediacy—of manifesting the will to record through the work of the line.”20

By situating Abu Zubaydah’s drawings within longer histories of political illustration, such as that of al-Ali’s, I do not mean to suggest that Abu Zubaydah’s drawings must be read as comics, but rather that there is an undeniable artistic sensibility at play in his drawings and that this sensibility may in fact be referencing other Palestinian visual culture. And more, that by virtue of being hand drawn, these images produce an embodied approach to witnessing that facilitates a less desensitized mode of contact with testimonials on the part of the viewer. To this end, Abu Zubaydah’s earlier drawings are visually stimulating, both creating a complex narrative universe for the viewer to decipher and functioning as a journalistic account of torture.

Figure 4 punctuates objects in such a way that they might be read as symbolic of Abu Zubaydah’s experience of captivity and also of the normalization of violence within the US military. This image seems to reference Guantánamo Bay directly, both through the surveillance camera displayed at the top right corner and the scorpion, which are known to inhabit the territory, at the bottom. The circle as a symbol occupying the frame’s perspective resonates with what psychoanalyst Marion Milner has written about “as denoting a hole, an empty body orifice, a gap, a wound, something not there[;] it can become confused with its aspect as symbolizing the de-differentiation of the ego.”21 That the circular symbol might signify negation is telling. The presence of multiple military guards throughout these drawings underscores the debilitating and violent effects of interactions between prisoners and military actors. Here, processes of identification become murderous as opposed to relational.

On a sonic level, the repeated use of the circle could denote a sound wave vibrating throughout the image.22 Indeed, the entire image is sounding across multiple spatiotemporal scenes of torture that Abu Zubaydah has experienced throughout the years. Showcasing symbols such as the scorpion, the sword, and the camera, all of which are rendered in a cartoonish nature, allows for certain details to come to the fore that might otherwise disappear. One might even argue that this image renders “a heavy metal aesthetic,” a sonic weight embedded within the image, which presses down on the viewer, producing an overwhelming sensation.23 Only Abu Zubaydah knows if these images are directly influenced by the use of music as stealth torture during interrogations, but listening for different sounds inside the frame takes seriously the unique singularity that Abu Zubaydah himself brings to the visual encounter with torture.24 How he then represents those encounters disrupts a number of dualities having to do with life, death, temporality, and psychic wholeness.

In a communication to his lawyer, Abu Zubaydah expounds a bit more on his interior life as it relates to time:

I had normal dreams and then would find myself waking up and talking to myself for a long time and not a couple of words but rather long sentences and then to finally realize that I was in a different world than the world of dreams. Other times I would have nightmares and would wake up screaming or cussing or trying to kick or hit something; or I would wake up screaming that spontaneous scream.25

Abu Zubayda’s contrasting the world against the world of dreams reflects the living death of torture, while also reminding the spectator of his own singularity, in which he is sometimes dreaming, at other times more disconnected and parting company with the world. He communicates his experiences of pain, suffering, and the loss of ground through his written testimony but also his drawings, which are of a different language entirely. Abu Zubaydah’s images might help those on the outside of torture enter into the scene of torture, but they also invite us to listen in on his story, recounted through shapes, delusions, and dreams.26

I am invested in listening to Abu Zubaydah’s images alongside his written testimonials precisely because together, they generate the sense of another form of life inside of captivity that cannot be apprehended solely through a framework that regards either as “mere representations of torture.” I am suggesting this form of life is at least partly predicated upon enduring indefinite detention and what the experience of waiting feels like. Abu Zubaydah’s drawings gesture toward a preoccupation with temporality, as shown through the recurring image of the hourglass, but also the time of disassociation—he moves in and out of the world of dreams unknowingly, an altogether different experience of mechanical time. And there is also the temporality of testimonial itself, in that Abu Zubaydah is present and precise with what he has endured for decades now. Through testimony he insists upon making intelligible his experience inside confinement for a larger public. Spoken through both the body and the aesthetic is Abu Zubaydah’s power to recapitulate a life.

Listening to an image is not about fixing the represented subject in place, but rather about holding open the possibility of movement and the self-transformation of that subject. Listening is also about being open to a subject’s uncertainty. It seems to me that Abu Zubaydah’s drawings invite us to look inward, toward the place where—in phenomenologist Gayle Salamon’s beautiful phrasing—life hides away.27 His withdrawal inward is perhaps a way to refuse being constituted solely by torture. These drawings allow access, though not total, to the life that at times must stay hidden. One reading of torture and spaces such as Guantánamo is that they foreclose relations, but I read Abu Zubaydah’s drawings as an intervention into that foreclosure. This is not to suggest that Abu Zubaydah’s drawings are liberatory, but that if one of the central aims of torture and interrogation is to break down voices such as Abu Zubaydah’s and make them fundamentally unintelligible to those on the outside, these drawings, then, sound in such a way that speech is no longer the only legitimate form of testimony.

This is only a cursory meditation on the different ways viewers might listen to these images and how they function as both legal evidence of torture but also Abu Zubaydah’s artistic imagination. And so, what is our responsibility to these images? The visuality of torture is a site through which to imagine a new, more relational approach to witnessing; via the image, the spectator might engage with Abu Zubaydah’s voice, his narrative of pain. His drawings, as a visual response to the slow death of detention, provide insight into the specific mechanisms of torture while also opening up new ways to question the limits and possibilities of recognition.

Abu Zubaydah’s drawings—his art—are a site for developing new visual grammars around how we decipher images of violence. His work propels those of us on the outside of captivity to commit ourselves to relational approaches to pain and suffering that facilitate abolitionist imaginaries, as opposed to merely empathetic ones. Here I gesture toward thinking about abolition as a sensibility, or what Ben-Moshe calls a “dis-epistemology,” in relation to our visual grammars. For Ben-Moshe, abolition is a “radical epistemology of knowing and unknowing.” Dis-epistemology, then, “is a giving way to other ways of knowing.”28 With this in mind I have approached the images within “How America Tortures” as an experiment in listening and looking for that which normally escapes the frame. I read Abu Zubaydah’s drawings as opportunities, then, to engage with his various lifeworlds within captivity; through them, although I cannot know him, I might come to better recognize him.

Michelle C. Velasquez-Potts is an educator and writer working at the intersections of feminist and queer thought. She is an Embrey Family Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Texas at Austin, where she teaches in the Center for Women’s and Gender Studies. Broadly, her work attempts to imagine more relational ways of approaching questions of state violence and punishment. She has published essays in Women and Performance, Public Culture, Abolition Journal, and Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex (AK Press, 2015) [michelle.potts@austin.utexas.edu].

- Thank you to the participants of the Faculty Development Program at UT Austin, where I first presented these ideas; the conversation and feedback were invaluable. Also thank you to Heather Rastovac and Sonya Merutka for reading and thinking with me. Finally, gratitude to Nicole Archer for her expert editing, insight, and encouragement.

Laurel E. Fletcher and Eric Stover, The Guantánamo Effect: Exposing the Consequences of U.S. Detention and Interrogation Practices (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 3. ↩ - For more on the objectives of the Enhanced Interrogation Program, see Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, The Senate Intelligence Committee Report on Torture: Executive Summary of Committee Study of the Central Intelligence Agency’s Detention and Interrogation Program (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2014). ↩

- See Mark P. Denbeaux, “How America Tortures,” Seton Hall University School of Law Center for Policy and Research, December 2, 2019, 56. ↩

- Denbeaux, “How America Tortures,” 10. See also Carol Rosenberg, “What the C.I.A.’s Torture Program Looked Like to the Tortured,” New York Times, December 4, 2019. ↩

- Rosenberg, “What the C.I.A.’s Torture Program Looked Like.” For more on questions of property rights and art created at Guantánamo Bay, see Carol Rosenberg, “After Years of Letting Captives Own Their Artwork, Pentagon Calls It U.S. Property: And May Burn It,” Miami Herald, November 16, 2017. ↩

- See Raymond Bonner and Tim Golden, “Pictures from an Interrogation: Drawings by Abu Zubaydah,” ProPublica, May 30, 2018. ↩

- For more on the relation between listening and visuality, see Fred Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” in Loss: The Politics of Mourning, ed. David L. Eng and David Kazanjian, 59–76 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003); Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017); and Michelle C. Velasquez-Potts, “Carceral Oversight: Force-Feeding and Visuality at Guantánamo Bay Detention Camp,” Public Culture 31, no. 3 (2019): 581–600. ↩

- I take seriously the psychiatric concerns expressed by victims in the wake of torture, but I also want to resist the framing of the tortured bodymind as abject. Following a disability justice politic, I contend that it is carceral regimes, such as torture, that are pathological and antithetical to relationality, as opposed to the individual(s). For more on the coercive logics of cure, see Eli Clare, Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017); Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013); and Sami Schalk, Bodyminds Reimagined: (Dis)ability, Race, and Gender in Black Women’s Speculative Fiction (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018). ↩

- For instance, Shaista Patel refers to the many Orientalist depictions of Arabs and Muslims circulating throughout the media as the “mad Muslim Terrorist.” See Patel, “Racing Madness: The Terrorizing Madness of the Post-9/11 Terrorist Body,” in Disability Incarcerated: Imprisonment and Disability in the United States and Canada, ed. Liat Ben-Moshe, Chris Chapman, and Allison C. Carey (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 201–16. Also important to note is how discourses of humanitarianism likewise deploy the language of psychology to argue that prisoners are traumatized victims, irreparably damaged by the effects of confinement. See Alison Howell, “Victims or Madmen? The Diagnostic Competition over ‘Terrorist’ Detainees at Guantánamo Bay,” International Political Sociology 1 (2007): 29–47. ↩

- Matt Apuzzo, Sheri Fink, and James Risen, “How U.S. Torture Left a Legacy of Damaged Minds,” New York Times, October 8, 2016. ↩

- Liat Ben-Moshe, Decarcerating Disability: Deinstitutionalization and Prison Abolition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 65. For more on the racial and gendered logics of the War on Terror and how anti-Blackness comes to be projected onto incarcerated Muslim men across counterterrorism sites, see Neel Ahuja, “Reversible Human: Rectal Feeding, Plasticity, and Racial Control in US Carceral Warfare,” Social Text 38, no. 2 (2020): 19–47. ↩

- Denbeaux, “How America Tortures,” 39. ↩

- “Discombobulating” was how James Mitchell, one of the CIA psychologists hired to develop the Enhanced Interrogation Techniques of the War on Terror, described the effects of walling. See James Mitchell deposition, Salim v. Mitchell¸ 2:15-CV-286-JLQ (US District Ct. for the Eastern District of Washington at Spokane, January 16, 2017), 108. ↩

- The comic studies term for these symbolic elements is “emanata.” ↩

- For more on the weaponization of sound or “sound torture,” see Suzanne G. Cusick, “Music as Torture/Music as Weapon,” in The Auditory Culture Reader,ed. Michael Bull and Les Back (New York: Routledge, 2016), 379–92. ↩

- Here we might also imagine the sound of a pen moving across a page, filling in the sides of the confinement box. ↩

- See Lori A. Allen, “The Polyvalent Politics of Martyr Commemorations in the Palestinian Intifada,” History and Memory 18, no. 2 (2006): 107–38, for more on martyr memorialization in the second Palestinian uprising. Also see Laleh Khalili, Heroes and Martyrs of Palestine: The Politics of National Commemoration (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007) for the commemoration of martyrs through Palestinian poster art. ↩

- See Orayb Aref Najjar, “Cartoons as a Site for the Construction of Palestinian Refugee Identity: An Exploratory Study of Cartoonist Naji al-Ali,” Journal of Communication Inquiry 31, no. 3 (2007): 255–85, for an analysis of cartoons in Palestinian cultural production, as well as for more on Handala as an iconic figure in Palestinian political/visual culture. ↩

- Nicole R. Fleetwood, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020), 3. ↩

- Hillary L. Chute, Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 212–13. Also worth noting are the resonances between Abu Zubaydah’s use of Christian imagery in the form of the cross and al-Ali’s drawing titled The Palestinian Jesus Christ, with the Key of His Home, Pines for Bethlehem. See Najjar, “Cartoons as a Site,” 272. ↩

- Marion Milner, The Hands of the Living God: An Account of a Psycho-Analytic Treatment (New York: Routledge, 1969), 466. ↩

- Many thanks to Nicole Archer for bringing this to my attention. ↩

- See Jay Miller, “What Makes Heavy Metal Heavy?,” Aesthetics for Birds, April 9, 2018. ↩

- For more on the use of heavy metal music to torture captives of the War on Terror, see Moustafa Bayoumi, “Disco Inferno,” Nation, December 8, 2005. ↩

- Bonner and Golden, “Pictures from an Interrogation.” ↩

- See Stefania Pandolfo, Knot of the Soul: Madness, Psychoanalysis, Islam (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), for a sustained discussion on the encounter with madness and psychosis through art. ↩

- Gayle Salamon, “‘The Place Where Life Hides Away’: Merleau-Ponty, Fanon, and the Location of Bodily Being,” Differences 17, no. 2 (2006): 96–112. ↩

- Ben-Moshe, Decarcerating Disability, 126. ↩