From Art Journal 80, no. 4 (Winter 2021)

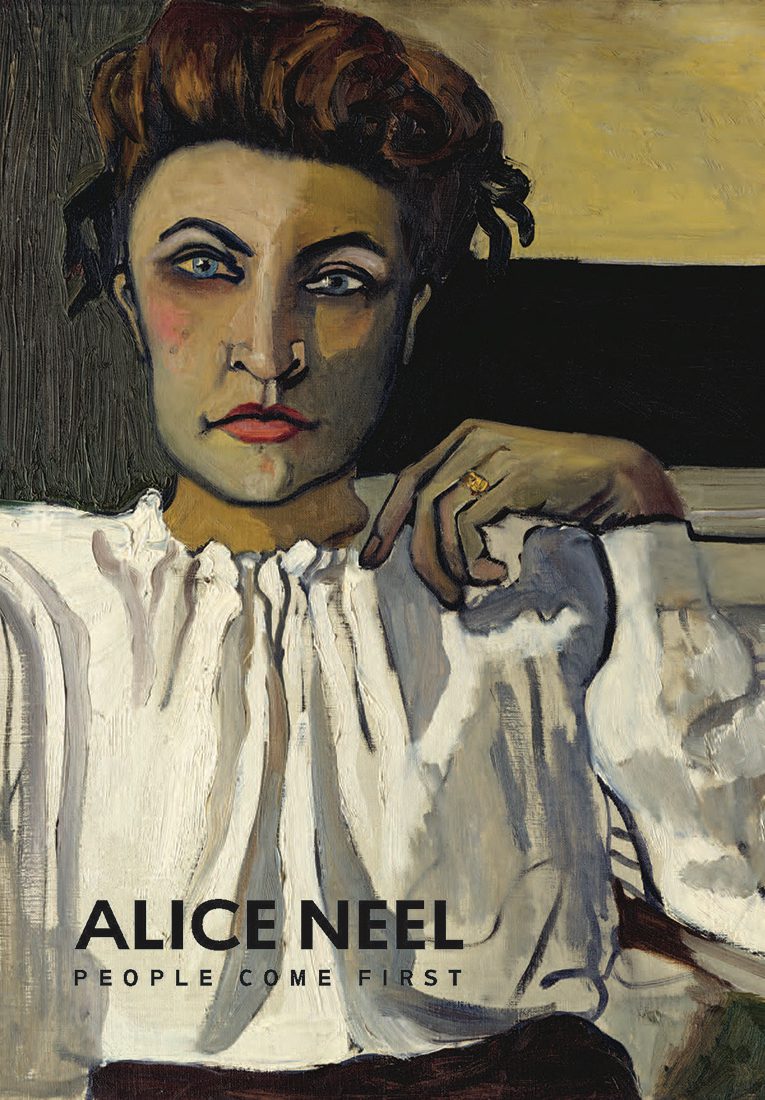

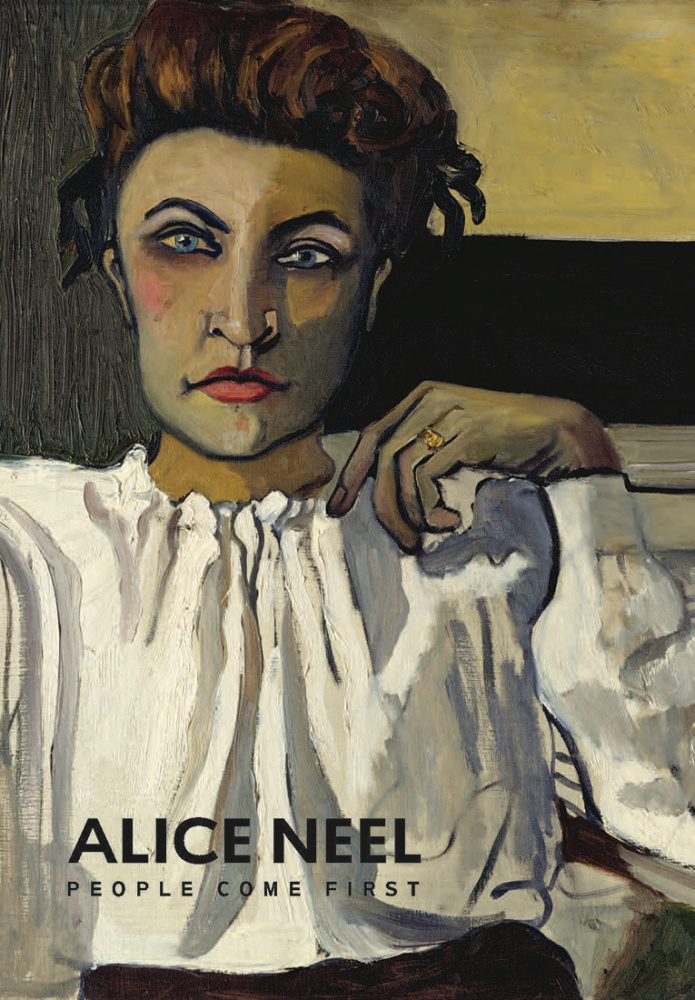

Kelly Baum and Randall Griffey. Alice Neel: People Come First. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021. 256 pp.; 201 color ills. $50

Alice Neel: People Come First. Exhibition organized by Kelly Baum and Randall Griffey. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, March 22–August 1, 2021; Guggenheim Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain, September 17, 2021–February 6, 2022; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, March 12–July 10, 2022

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s retrospective of the work of Alice Neel could not have come at a better time. After more than a year of physical isolation, of faces obscured by masks or diminished by the flattened affect and failed gazes of the Zoom screen, to encounter all these paintings of people, of New Yorkers, is like a balm for the soul. The city’s museums have been open since August 2020; we wear our masks, have our temperatures checked, carry our coats, and notice a subtle yet visible difference in our fellow visitors. Without the swell of tourists, we are all New Yorkers, the New Yorkers who stayed behind. Alice Neel: People Come First feels like a life-restoring gift to the people of New York, and it is a welcome one.

The beginning of the exhibition conforms to traditional chronological norms. We learn that Neel was raised in Pennsylvania and spent a year in Cuba before moving to New York. She trained under the influential Ashcan School painter Robert Henri. Alongside the typical juvenilia associated with this type of staging are some of the most daringly intimate works of her oeuvre. Rare self-portrait scenes of Neel and her postcoital lover, such as Alienation and Untitled (Alice Neel and John Rothschild in the Bathroom), both from 1935, can be seen as a powerful feminist riposte to the misogynistic realism of Neue Sachlichkeit artists, such as George Grosz. Indeed, her bohemian embrace of sexual freedom coupled with a serious commitment to Marxist politics seem more at home in the Weimar Republic than what we are used to seeing of interwar New York. So much so that Neel’s perspective on the 1930s American Left shows us more diversity in its cast of characters and more humanity in its staging of life—with both desire and despair vividly presented—than we get from equivalent socially engaged contemporaries, such as Ben Shahn.

The exhibition’s introductory nod toward chronology soon disappears, and viewers encounter an initially puzzling oscillation between different moments in Neel’s sixty-year-long career. As we move through the galleries, it becomes clear that this method of curatorial staging allows us to notice painterly developments without their reduction to evolutionary hierarchies of artistic progress and to see important continuities between Depression-era works and the heyday of the Women’s Movement and pre-AIDS Gay Rights of the 1970s and early 1980s. Portraiture is clearly Neel’s dominant mode, with still-life and cityscape scenes as regular secondary subjects. The rearrangement of the works into cross-decade conversations allows us to read these portraits as a kind of archive. This is an archive of New York’s political radicals, feminists, artists, writers, and cultural figures of the 1930s through the early 1980s, as well as many otherwise unknown working-class women, children, and the occasional man, including a significant number of Black and Black Hispanic neighbors, employees, and relatives. Neel lived in Greenwich Village from the late 1920s to 1938, when she moved uptown to Spanish Harlem, where she settled for almost twenty-five years. From 1962 until her death in 1984, she lived across town on West 107th Street and Broadway, in a neighborhood that was not yet the bland bourgeois setting that we see in the TV sitcom Seinfeld. As a chronicler of New York’s social milieu and a painter of its social history, as Neel saw her project, she shows a geopolitical lifeworld that diverges from the narrow downtown focus of most modern American art history.

The curators, Kelly Baum and Randall Griffey, taking their lead from Neel herself, reject the label of portrait painter. When “portrait” qualifies the identity of “painter,” much like when “woman” does, it diminishes the seriousness of the practice and relegates Neel’s artistic project to the outmoded, the traditional, and the academic. But the portrait is what she paints. Moreover, her lifelong engagement with portraiture might force us to reexamine the knee-jerk dismissal of the genre. Yet, there is a good deal of dancing around this term in the various catalog essays. Baum and Griffey propose the neologism “anarchic humanist” as a politically robust alternative to the traditionally bourgeois genre of portraiture (a peculiar political misnomer for an artist with such strong communist roots). However, I felt that the greatest strength of this exhibition lies in the way in which Neel’s work makes portraiture significant to modern painting, and dodging the topic felt like a lost opportunity.

Rather than see Neel as an exception to the sweeping narrative of American modernism, can we not see her as opening up different trajectories for American painting? One way is through her decentering of New York’s geopolitical milieus. This is vitally present in the complex and ambiguous confrontations we see in her portraits of Black and Black Hispanic subjects, many of them children. Susanna V. Temkin’s catalog essay on Neel’s representation of Spanish Harlem, “Siempre en la Calle,” challenges the scholarly pattern of seeing the artist’s twenty-four years in El Barrio as some kind of exile from the art world. She gives a useful account of the cultural history of the neighborhood that includes tantalizing references to the photographic portraiture of Sophie Rivera and Hiram Maristany (not to mention contemporary Latinx painters Jordan Casteel and David Antonio Cruz). This focus on place opens the door for more substantial histories of New York’s other art worlds.

The final room of the exhibition intersperses a few tentative comparison works as the (not always satisfying) curatorial equivalent of academic footnotes. A Vincent van Gogh and an Henri portrait stand for two poles of artistic influence without really telling us more than this, but the insertion of one of the German photographer August Sander’s images from his interwar project Citizens of the Twentieth Century opens up Neel’s relationship to the practice of portraiture in new ways. While the portrait is seen as a very minor genre in twentieth-century painting, we might understand it as having ceded much of its ground to photography. My above suggestion that Neel’s oeuvre of portraits forms a kind of archive makes this reference to Sander’s typological method particularly apropos. But there are other ways in which photography might help us to see Neel’s portraits in a different light. Superficially, many of her paintings of people look like photographs. Sitters almost all offer a direct address to the viewer to varying effects. Some faces are seemingly caught in momentary slack blankness (e.g., Ginny in a Striped Shirt, 1969) or with a posed smile (e.g., Fuller Brush Man, 1965). Limbs are arranged in awkward tension (e.g., Puerto Rican Girl on a Chair, 1949) or self-possessed confidence (e.g., Richard in the Era of the Corporation, 1978–79). All of these details evoke the arrested moment of the photographic portrait.

Thinking further about photography’s twentieth-century hijacking of portraiture’s position helps us to see the specificity of Neel as a portrait painter. I want to propose another historical comparison as a late-career counterpoint to Sander in the portrait photography of Richard Avedon. His poignantly blank-faced image of Marilyn Monroe, body and spirit seemingly drawn down into pensive despair by the weight of her breasts, and the monumental group portraits of the counterculture denizens of Andy Warhol’s Factory share an affinity with the psychological complexity of Neel’s paintings, not least because she also painted some of Warhol’s people as well as an incredible portrait of the artist himself. The latter is equal in its tenderness and cruelty, with operating scars bared, eyes closed, and corset exposed (surely a riposte to Avedon’s sexy leather-clad depiction of Warhol from 1969). Yet, as far as I can gather, she generally did not use photography as part of her method. And when she did, such as in her 1970 commissioned portrait of Kate Millett (not in this exhibition), the outcome is much less effective. Being together with a live sitter was crucial for the effect that Neel achieves. Not just because of the figurative economy of her brushwork in its rendering of psychological nuance, but also in the unfinished areas of bare canvas, the impasto slabs of painted color, and the scumble and stain of spare and excess paint. Neel’s painterly style is most fully addressed in an essay by Julia Bryan-Wilson, inspired by Mira Schor, “Alice Neel’s ‘Good Abstract Qualities.’”

Bryan-Wilson also avoids discussing any of Neel’s portraits, yet the brilliance of the 1970 portrait of Warhol, for example, lies as much in these abstract elements as it does in the figurative rendering of his pose. Neel’s careful scrutiny of his pinkish face and the still livid scarring of the torso is only made more pronounced by the reliance on negative space and blank canvas. The ghost of a couch appears in a single dirty Indian yellow stroke, dry and thinning in places, but, as it meets the unfinished left knee, the line bleeds a wisp of turpentine-soaked paint like a pus stain on a bandage. The cloud of pale blue background surrounding his upper torso and rubbing out to nothingness seems to hug the crippled figure. The vivid cleanliness of this abstract passage in a shade of sky blue contrasts with the soiled blue-brown tangle of line and washed paint that approximates the impresario artist’s clenched hands. All of this is contained in a highly structured composition that holds the failing body in its classical grip.

Because Neel’s relationship to portraiture as a genre is not seriously considered in the catalog essays, we are not really given much of an account of her working method. A practice of sketching is suggested and briefly examined by Griffey in his discussion of the portraits of the feminist art historian Mary Garrard and the feminist poet Adrienne Rich. An account of Neel’s assistant reaching out to a gay couple that she just met requesting that they come and pose for her gives fascinating insight into her forceful personality. The pair, the Fluxus artist Geoffrey Hendricks and his boyfriend Brian Buczak, were instructed to wear the same clothes that they had on when she met them the previous evening and asked to come to the studio that very afternoon. Likewise, we learn that some sitters were sought out and others approached Neel to paint them under commission. This structural difference in the dynamic of painter and subject tells us something about Neel’s ambivalence toward feminists and lesbians (Garrard, Rich, and Millett were all commissioned portraits) and sympathy for gay men and male-to-female transsexuals, such as the performer and Warhol superstar Jackie Curtis, whom she painted twice (as a girl and as a boy). But, as a rule, these transactional differences do not make the commissioned works any less interesting. Like Avedon, her paintings disclose the encounter between the artist and the subject, suspended between what the artist grasps in, to use Aby Warburg’s description, the “intimate contact between portrayer and portrayed” and what happens as a surprise even to herself.1 Like the 1970 painting of Linda Nochlin and her daughter. The feminist art historian is quoted remembering Neel’s remark that, “You know, you don’t seem so anxious, but that’s how you come out” (78). The live encounter is crucial here, and its absence is why the Millett portrait is affectively flat. It is also why Neel’s remarkable series of portraits showing heavily pregnant nudes contains some of the most important works in her oeuvre. The complicated inner struggle of the sitter with the transformation in her bodily matter is writ large in ambivalent facial expressions that range from openly hostile to despairing. Baum’s essay is particularly strong on these works.

I found myself fantasizing a list of contemporary artists who could enter a dialogue with Neel on portraiture as a vital twenty-first-century genre. It is no coincidence, I think, that the most innovative and dynamic reinvention of portraiture as a contemporary art form (in both painting and photography) is seen in the work of artists of color. Kerry James Marshall, Amy Sherald, and Kehinde Wiley offer important engagements with vernacular traditions, popular culture, and painting’s long history as an elevated high art form. LaToya Ruby Frazier, Naima Green, Jon Henry, and Deana Lawson are among those innovating in related ways for contemporary photography. Like Neel, Black artists in America understand portraiture’s enduring political power to assert humanist values. Indeed, the defense of humanism—as a political and ethical imperative for Neel—is one of the framing ideas advanced by the curators of this exhibition. Contemporary audiences must surely feel the life-affirming necessity of the live human encounter all the more profoundly after months of social isolation and ongoing political, social, and existential uncertainty. Neel’s portraits require a togetherness of artist and sitter that discloses a broad spectrum of human encounters held in mysterious alchemy by the matter of paint.

Siona Wilson is associate professor of art history at the College of Staten Island and the Graduate Center, the City University of New York.

- Aby Warburg, “The Art of Portraiture and the Florentine Bourgeoisie: Domenico Ghirlandaio in the Santa Trinita; The Portraits of Lorenzo de’ Medici and His Household” (1902), in The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity, trans. David Britt (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 1999), 187. ↩