This paper grew out of “The Color of Joy: Rethinking Critical Race Visual Culture,” a panel discussion at the 2021 College Art Association Annual Conference. The panel was organized by crystal am nelson and Michelle Yee who invited me to discuss my work, which has engaged with issues of race and racial formation for over two decades but is more often associated with trauma than joy, and so I welcomed the panel’s pairing of critical race visual culture with BIPOC1 cultural practices. At that time I also knew I wanted to revisit my 2018 billboard project in light of the then-recent 2021 US Capitol attack.

Here I will draw from several bodies of my work, including two series, Erased Lynching and Profiled, and an exhibition entitled Unseen: Our Past in a New light, Ken Gonzales-Day and Titus Kaphar, ending with my Constellations series, to share the different ways in which my exploration of race, whiteness, and absence have informed my practice.

Erased Lynching Series

On the morning of January 7, 2021, I was watching news coverage on the previous day’s attack on the United States Capitol and was instantly reminded of the historic images of lynching that I had studied for so many years. News clips on that day repeatedly showed thousands of protesters as they transformed into a frenzied mob and gave far-right groups like the Oath Keepers, Proud Boys, and Three Percenters national attention.

Around noon on January 6, 2021, Donald Trump falsely asserted to a crowd of supporters on the National Mall that the recent presidential election had been stolen. He further incited the crowd when he said, “We fight like hell and if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.”2 It was then that thousands of Trump supporters stormed the US Capitol, disrupted lawmakers, and attempted to overturn Trump’s defeat in the 2020 election. The world watched in horror as democracy teetered on the brink of destruction. Makeshift gallows were erected. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other members of Congress had their offices looted and vandalized. Staff members hid under tables and locked doors for safety. In the end, five people died and more than 140 were injured.3

I was in the middle of selecting images for the panel presentation and knew I had to begin with a 2006 image from the Erased Lynching series that appeared as a billboard in 2018. I had added the words “democracies can fail” to the right of the image for the billboard presentation after I heard these words spoken by former President Obama at an event in Los Angeles. The billboard was one of 300 designed by artists and activists as part of the 50 State Initiative, which was a national effort to get people out to vote and took place in the weeks leading up to the 2018 midterm elections. This massive project was organized and implemented by the artist collective For Freedoms, founded by artists Hank Willis Thoma and Eric Gottesman “to model and increase creative civic engagement, discourse, and direct action.”4

The photograph on the billboard depicts a mob after they had lynched Thomas Thurmond and John Holmes, two white men, in Saint James Park in San Jose, California on November 26, 1933.5 As with other images in the Erased Lynching series (over sixty images), I removed the victims and the ropes from archival images of lynching as part of an artistic strategy to draw the viewer’s attention away from the spectacle of death and toward the social conditions that made such actions possible in the first place. I wanted the viewer to see whiteness in a new way and to point to those affective attachments that made such collective acts of violence acceptable to these individuals in the first place. Which is to say that this double lynching was not the spontaneous act of a mob, but was planned, and included elements of previous lynchings. This double lynching had been planned and announced in advance, which helps explain how and why the crowd numbered in the thousands. The two men were accused of kidnapping Brooke Hart, the twenty-two-year-old son of a prominent businessman, and were being held in the jail across from the park when his body was discovered.6 Some readers might recall that the search for the kidnappers/killers of the Lindbergh baby was still ongoing in 1933, which only added to the explosiveness of the Hart case. Even California’s Governor “Sunny Jim” Rolph embraced the lynching as a “fine lesson to the whole nation,” reflecting popular sentiments on kidnapping at that time.7

I wanted to draw a connection between lynching and the events of January 6, 2021 and to suggest that collective acts of (mob) violence must be linked to the corrosive effects of vigilantism, white nationalism, and fascism in this country. The case is also a useful reminder that images of lynching were produced and mailed as postcards across the United States and extended the terror represented in the lynching of over 4,400 African Americans, not to mention the victims who were Latinx, BIPOC, white, or immigrants lynched across the United States since its founding.8 The fact that these two men were white only heightens our ability to see connections between lynching and whiteness. Having examined and studied photographic images of racial and ethnic terror, from lynching to the Holocaust, I could not help but be horrified by the frenzied excitement of those who would have ended US democracy on that day.

Let us consider another image. In Sunday Early, 1933, we see a group of adults from the same lynching as the one depicted on the billboard. Chillingly, Thurmond and Holmes may have still been hanging from the trees when the photograph was taken. The man and woman appear to be filled with a kind of joy as they posed by the tree. Other figures are touching the places where the bark had been removed. As with many lynching cases, the trees had to be cut down to keep souvenir hunters from taking every inch. The 2021 Capitol attack protesters, rioters, and insurgents looked no less exuberant as I watched them on the news, and it was clear to me that whiteness is not about race as much as it is about the imaginary of race. The people in the crowd in the lynching image smile, laugh, and stare blankly, their behaviors reminiscent of those of the rioters at the Capitol building, who committed various violent acts and took selfies. As the American novelist Toni Morrison wrote, seeming to speak to our own historical moment, “I know the world is bruised and bleeding, and though it is important not to ignore its pain, it is also critical to refuse to succumb to its malevolence. Like failure, chaos contains information that can lead to knowledge—even wisdom. Like art.”9 Morrison hints at a very different kind of joy, the kind that art can bring, even in the face of affects like anguish, anger, fear, and of course, terror.

It is important to note that my own work on lynching began as a response to real world vigilantes who emerged along the US-Mexico border back in the early 2000s, when groups like the Minuteman Project were symbolic of a wave of anti-Mexican, anti-Latinx, anti-immigration rhetoric that was being propagated by then-president George W. Bush. By the time I began working on my book Lynching in the West: 1850–1935, new Minutemen branches were popping up by the dozen. I wrote on California’s history of lynching at a time when few were willing to acknowledge the brutal killing and racial terror faced by many Latinx communities in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I documented over 354 cases of lynching in the state of California and changed, or at least tried to change, the narrative. In California, the majority of lynching victims were BIPOC (Asian, Black, Latinx, and Native American) with Latinx victims making up the largest single group, at over 38 percent of the total case list.10 This research was integral to three of my photographic projects: Erased Lynchings, already discussed; Searching for California Hang Trees, where I went out looking for possible sites; and Memento Mori, a series of portraits in which contemporary individuals stand in for those killed by lynch mobs and vigilantes (in California). While no artwork can address the ongoing pain and trauma of lynching to African Americans and their families, my project was produced in solidarity with a wave of new scholarship that emerged on lynching in the early 2000s and that helped to raise awareness of the history of lynching in California and nationwide.

Ken Gonzales-Day, Sunday Early, 2019, 43 x 30 in. (109.2 x 76.2 cm) manipulated photograph, ink on rag paper (artwork © Ken Gonzales-Day/Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, provided by the artist)

Ken Gonzales-Day, Second Garrote, from the series Searching for California Hang Trees, 2014, 50 x 62 in. (127 x 157.5 cm), manipulated photograph, ink on rag paper (artwork © Ken Gonzales-Day/Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, provided by the artist)

In much of my work on lynching I utilize “erasure” and “absence” as artistic strategies to disrupt the spectacle of violence and the romanticization of vigilantism. To erase something can be seen as an act of displacement or destruction. However, in my work, I turn erasure into a site of production, and absence into a constructive presence, both of which critically engage viewers and invite new meaning. The image is altered, but the erasure is rarely complete and there are often clues that remain in the presentation of the work, in the naming of the piece, and in the language that surrounds the series, from the wall label to my own writing on the subject. In this way, absence reveals itself as a presence. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes (1915–1980) wrote, “Affect was what I didn’t want to reduce; being irreducible, it was thereby what I wanted, what I ought to reduce the Photograph to.”11 However, a photograph is not only affect because we experience it from a place, a perspective. We take on cultural beliefs from our surroundings and are constantly testing them, and it is the images from other historical periods that make the differences most visible, from vernacular photography to lynching postcards.

For me, the erasure of Latinx bodies from the history of racialized violence in America was an affect, a wound, as Barthes might say, that only deepened as Latinx bodies continued to be vilified before and during the Trump presidency. Readers may recall then-candidate Trump’s now infamous quote, “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”12

It was for this reason that, when mounting an exhibition of my work at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, just blocks from the White House, that I wanted to put the Erased Lynching series and other works on view. It was a way of using erasure and absence, artistic strategies that I have employed for over two decades, to invite viewers to consider histories that they didn’t even know were missing. One of the works included in the exhibition was Disguised Bandit, and it depicts US soldiers in uniform after they have lynched a Mexican “bandit” along the US-Mexico border sometime between 1913 and 1919.13 Like other works in the series, I erased the body and the rope but left the soldiers so that the viewer might focus on their smiling and grinning faces, might consider the presence of the camera, and might even ponder the ghostly pantomime of hands as they curled around the now-missing rope and the too-familiar characterization of Latinx bodies as those of bandits and criminals, signaled by the text which remained unaltered along the bottom of the image.

Profiled Series

The Profiled series (2002 ongoing) represented a shift in my work: it grew out of my research on lynching but focused on the idea of race as represented in and by the plaster life casts, plaster copies, and polychromed sculptural displays of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which often stood in for, or in contrast to, BIPOC cultures and communities. With Untitled, 2010, taken while I was a visiting scholar at the Getty Research Institute, I was thinking about the intersection between critical race theory and how sculptural depictions of race function in museums and museum collections. In this case, I was looking for, and photographing, representations of race in the museum’s bust collection and then taking the final resulting photograph out of the museum and showing it in the streets of Los Angeles as a billboard. The piece was commissioned by the MAK Center for Art and Architecture in West Hollywood for a citywide exhibition of billboards entitled, How Many Billboards? Art in Stead, in 2010 and later included as a part of the 50 State Initiative in 2018. Bust of a Young Man (on the left in the above image) is from 1520 and is by the Italian sculptor known as Antico (Pier Jacopo Alari-Bonacolsi). Bust of a Man (on the right) was carved in 1758 by Francis Harwood, an English sculptor, and depicts an unidentified Black man. We don’t know the names of these two men or who commissioned the sculptures. We don’t even know if they were modeled after specific individuals. I composed the work digitally and intentionally left a large expanse of white space in the center as a place marker for the unknown and as a way of speaking to the physical displacement of people though through conquest, colonization, and slavery. For me, the work was about Black and Brown diasporas, and mounting the work in the street was a way of giving these works a certain amount of agency. The piece was also about marriage equality and the intersectional complexity I experienced as a queer artist of mixed ancestry.

Some will remember that in 2008 voters in California passed a measure called Proposition 8, which banned same-sex marriages, and this proposition was being challenged in the courts when I made the billboard. My own same-sex marriage had been invalidated by the state recorder after the courts deemed the same-sex marriages authorized by then-mayor of the city of San Francisco, Gavin Newsom, invalid. The law banning same-sex marriage was overturned several months after the billboard came down. In 2018, the image took on new meaning as issues around voting rights increasingly made national headlines.

Another work, created as a companion piece but not exhibited until 2011, was Untitled, 2010, featuring Bust of an African Woman by Henry Weekes and Bust of Mm. Adélaïde Julie Mirleau de Neuville, née Garnier d’Isle by Jean-Baptiste Pigalle. In creating this piece, which was first exhibited as a wallpaper and later commissioned billboard sized for the side of the Bass Art Museum in Miami, I sought to once again engage with historical depictions of race, presented in profile, in reference to recent occurrences of racial profiling. The artists had sculpted them in stone and each work depicted curly hair, slight double chins, cute button noses, and other features that seemed specific to individuals. Yet most tellingly, when comparing the busts, viewers often described the sculptural differences in racial terms, or as types, to which I often respond that what the viewer is really looking at is a composited photographic image of two blocks of stone, and that, of course, stone has no race. Part of the strength of this work is that it reminds viewers that race, like gender, is a social and historical construct that we carry within us, and which only we have the power to change.

These two works point to the power of institutions, but, equally important, they also point to the potential capacity of museums to change the stories they tell about their collections. The fact that I was invited to work with this and other collections also says a lot about the potential for even greater change.

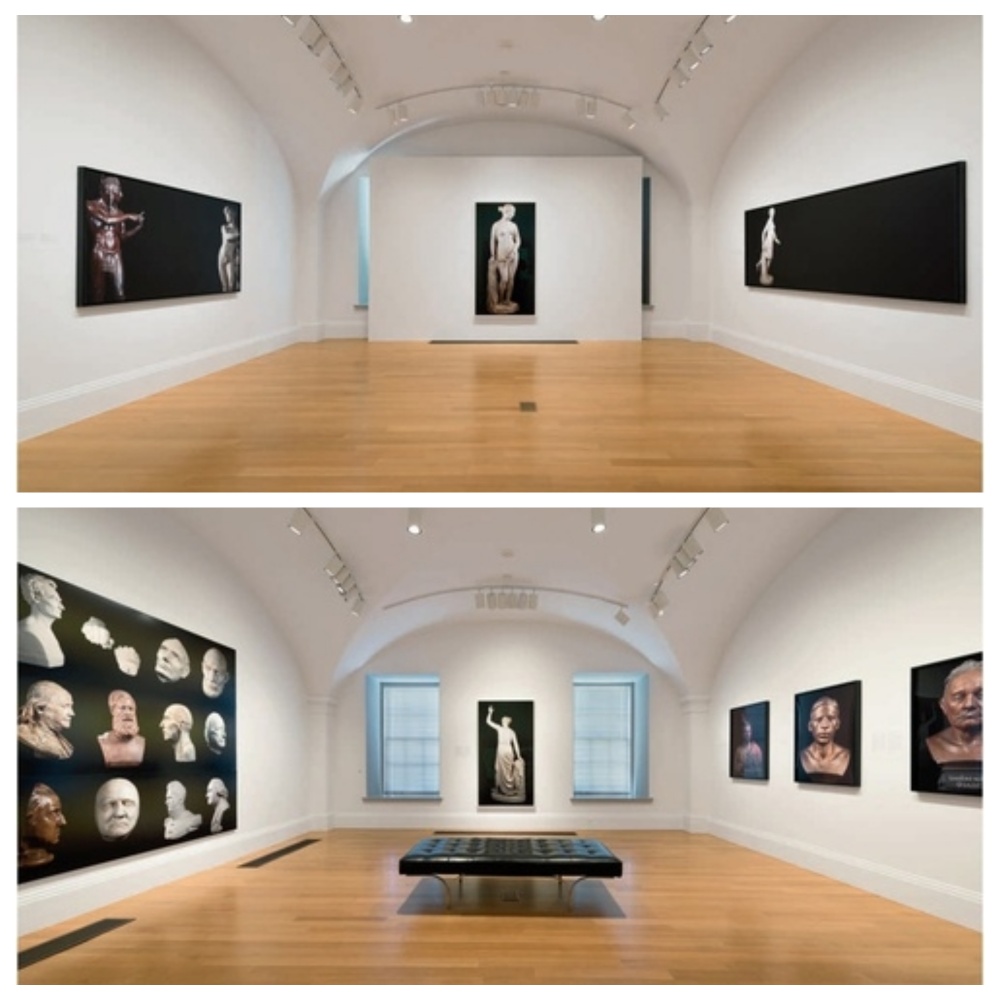

Unseen

In 2018, my work was included in a two-person exhibition entitled Unseen: Our Past in a New Light, Ken Gonzales-Day and Titus Kaphar, curated by Taína Caragol, curator of Latino Art and History, and Asma Naeem, then curator of Prints and Drawing and Time-Based Media at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. Each curator was given three rooms and worked closely with the artists they had selected. I organized the work into three sections entitled Absence, Displacement, and Naming as a way of introducing visitors to my practice. The room entitled Absence included the Erased Lynching series which, as noted in the room, sought to include missing histories and to draw attention to the absence of this history on multiple fronts. Displacement was the name of the second room and it sought to show allegorical depictions of race from museums, assembled and arranged to invite the viewer to question the art historical canon and images of whiteness; it included the image of the two marble busts discussed above. The last room was titled Naming, and viewers were invited to consider who is and who is not included in institutional collections, and the power of language. The room displayed works from three Smithsonian institutions arranged around a central photographic image of America (1848–50), a plaster study by Hiram Powers, which I had photographed from the back so that Powers’s allegorical figure of America (as a bare-chested white woman with arm raised) would have her back turned to the viewer.

On the left side of the nearly life-size image of America were hung photographs I had taken of plasters of some of the men (George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Benjamin Franklin, Marcel Duchamp, and others) historically collected by the Smithsonian institutions, and on the right side of the room were images of plaster busts of Native Americans I had photographed in storage facilities, including Bust of Shonke Mon thi^. Part of the intention for this room was to increase the representation of Native people in the National Portrait Gallery and to invite dialog around who is and is not included in our national narrative.

Taína reached out to the Tribal Historic Preservation Offices of several nations, tribal leaders, and various stakeholders in planning the exhibition. We also consulted with curators from several Smithsonian institutions and Dr. Steven Pratt, the great-grandson of Shonke Mon thi^ (b. unknown, d. ca.1919) of the Osage nation. We were able to exhibit a number of previously undisplayed works and to share some of my research on these individuals. Work that has only just begun.

Constellations

Finally, I wanted to close with a brief mention of a recent body of work entitled Constellations, included in Diálogos, an exhibition curated by Patrick Charpenel and Susanna Temkin to coincide with New York’s El Museo del Barrio’s 50th anniversary, and presented by Luis De Jesus Los Angeles at Frieze New York in 2019. I started by thinking about the different ways cultures have interpreted the stars and wanted to draw parallels with the different ways that cultural historians have interpreted objects. The resulting photographic images represented a series of new constellations, or arrangements, assembled from photographs I took of the permanent collections at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Royal Cast Collection in Copenhagen, among others.

Working with museum curators, collection management professionals, and stakeholders, I identified, located, and photographed hundreds of works as an exploration of racial formation in the fields of both studio art and art history.

For me, the series began with the myth of whiteness as imagined by foundational figures in the field of art history like Johann Winckelmann and embodied in the collections represented in the Royal Cast Collection in Copenhagen, and other similar cast collections. By incorporating underrepresented historical figures in the series alongside objects from dominant art historical narratives, I sought to highlight the organizational structure behind each cultural, institutional, or disciplinary constellation.

In photographing these objects, I came to appreciate their physicality as well as the network of individuals who have contributed to their continued existence, sometimes against incredible odds, or despite their maker’s original intentions or uses. In this way, this project extended questions around absence, represented by fragments, copies, casts, and artifacts.

In Américas (large constellation), 2019, I assembled works from Mexico and Colombia from LACMA’s Ancient Americas collection. The museum’s pre-Columbian collection was built around a gift from Southern California collector Constance McCormick Fearing and a purchase from businessman Proctor Stafford. More recent additions include donations from Camilla Chandler Frost, sister of Otis Chandler, and Stephen and Claudia Muñoz-Kramer of Atlanta, all of which have brought the collection to nearly two and a half thousand objects. Many of these objects come from burial sites in Mexico and across the Americas. In a city with many different Latinx communities and individuals, I wanted to create something that might speak to my own Latinx ancestors. Spending time with these objects was deeply moving and reflected back on my search for Latinx art and artists in museum collections, questions around provenance, and the historical and physical distance of these objects from those who made them. In my artist’s talks, I have read the label title out loud to emphasize the ways in which museum language fails to express our experiences as artists, as viewers, as spiritual beings, as affective beings with attachments both real and imagined, extant and lost. In looking for works by Latinx artists in the collection I created new works about that absence.

Ken Gonzales-Day, Constellations, 2019, series of photographs, (artwork © Ken Gonzales-Day/Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, provided by the artist)

Ken Gonzales-Day, Americas (large constellation), 2019, montage of photographs, ink on Canson PhotoSatin paper, 40 x 50 in. (101.6 cm x 127 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art (artwork © Ken Gonzales-Day/Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, provided by the artist)

With Constellations, I created clusters of works brought together by economic, cultural, and disciplinary forces that mirror the (art) historical conditions from which they were formed, and which could be assembled and arranged in new ways as part of a decolonial strategy. Collectively, I hope that this and the other projects discussed in this paper demonstrate how my practice has employed absence and erasure to invite viewers to consider the unseen and the unknown, and to model one perspective on critical race visual culture.

Ken Gonzales-Day is an artist and the Fletcher Jones chair in art at Scripps College, Claremont, California.

- Defined as Black, Indigenous, and people of color. ↩

- Calvin Woodward, “Trump’s Call to Action Distorted in Debate,” AP NEWS, AP Fact Check, January 13, 2021. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Forfreedoms.com. ↩

- Ken Gonzales-Day, Lynching in the West: 1850–1935 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006). ↩

- Harry Farrell, Swift Justice: Murder and Vengeance in a California Town (Macmillan, 1993), 242. ↩

- Ibid., 242. ↩

- Equal Justice Initiative, Lynching in America (2017); William Carrigan and Clive Webb, Forgotten Dean: Mob Violence against Mexicans in the United States (Oxford, 2013). The 1908 Comstock Act prohibited the sending of lynching postcards. Linda Kim, “A Law of Unintended Consequences: United States Postal Censorship of Lynching Postcards,” Visual Resources 28, no. 2 (2012). ↩

- Toni Morrison, “No Place for Self-Pity, No Room for Fear,” The Nation (April 6, 2015). ↩

- Gonzales-Day, 2006. ↩

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982), 21. ↩

- Michelle Ye Hee Lee, “Donald Trump’s False Comments Connecting Mexican Immigrants and Crime,” Washington Post, July 8, 2015. ↩

- “Common Threads,” US Department of Defense. Accessed April 17. ↩