Editor’s Note:

From the AJO Archives revisits past artists’ projects, conversations, interviews, and scholarly essays as part of our editorial work to place contemporary art practice in conversation with our archives.

We’ve paired the recent Contemporary Projects commission, Pato Hebert’s Malapropisms: Track Changes (January 18, 2024), in which the artist-organizer draws connections between his work on HIV-prevention and advocacy to addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, with this interview in which Rudy Lemcke discusses the poetics and politics of AIDS in light of his work in the 2014-16 traveling exhibition Art AIDS America.

I first encountered Rudy Lemcke’s work at Picturing AIDS: 1986–96, a retrospective of his AIDS artwork at the San Francisco LGBT Community Center in 2007. I was particularly moved by his video Where the Buffalo Roam (2007), in which Lemcke uses John Cage’s musical composition Perilous Night (1943–44) as an editing framework for juxtaposing documentation of ACT UP protests with evocative images of slain buffalo. In December 2014, Rudy and I sat down in his studio in San Francisco, California, for a conversation about his work. We discussed the poetics and politics of AIDS in light of his work in the traveling exhibition Art AIDS America, cocurated by Jonathan D. Katz and Rock Hushka.

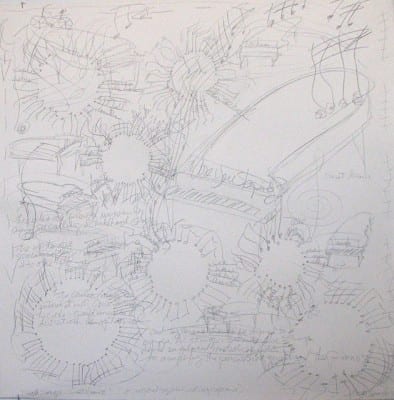

Tina Takemoto: I understand that some of your work was inspired by John Cage. Can you talk about how you met Cage, and how he influenced your approach to the drawings that are included in the Art AIDS America exhibition?

Rudy Lemcke: In 1985 I met Cage at the alternative art space La Mamelle in San Francisco, at his reception for The First Meeting of the Satie Society. For this piece, Cage worked with two computer programmers who input texts from Thoreau, Duchamp, McLuhan, and James Joyce. They wrote an algorithm that generated mesostic poems from random configurations of words that were “performed” live on a computer screen. A mesostic poem has a word or phrase written vertically and a series of horizontal words or phrases intersecting the vertical phrase. I was working with ideas of language and temporality and creating performance notations and installations that were deeply indebted to Cage, so this was an important moment for me as an artist.

The mid-1980s was also a time when AIDS entered our world. I was particularly struck by how AIDS as an idea was manifesting in different ways for various people and elicited a broad range of representations and responses. In my work I wanted to reflect on AIDS not only as a biological event but also as a complex cultural phenomenon that had complicated meanings. I was reading Finnegans Wake and loved how Joyce invented beautiful words that could subtly shift the meaning of a sentence. The words made sense but also appeared as nonsense. I started writing down Joycean words that had a certain feeling, tone, and resonance. Cage’s mesostic poems came to mind, and I thought of making AIDS poems from the words I had collected. I called this series of drawings Fin Again(s) Wake. I think of them as drawings but also as a type of writing or notation that came out of my earlier work in which I used scores as the conceptual structure for generating installations. For instance, in my 1979 untitled performance installation for breathing, I marked the ground with chalk. The Xs indicated where viewers should inhale, exhale, and hold their breath. The installation was less about formal spatial relationships than the temporal aspects of the performance notations.

Takemoto: Were all the words that you used in your mesostic poems taken from Finnegans Wake?

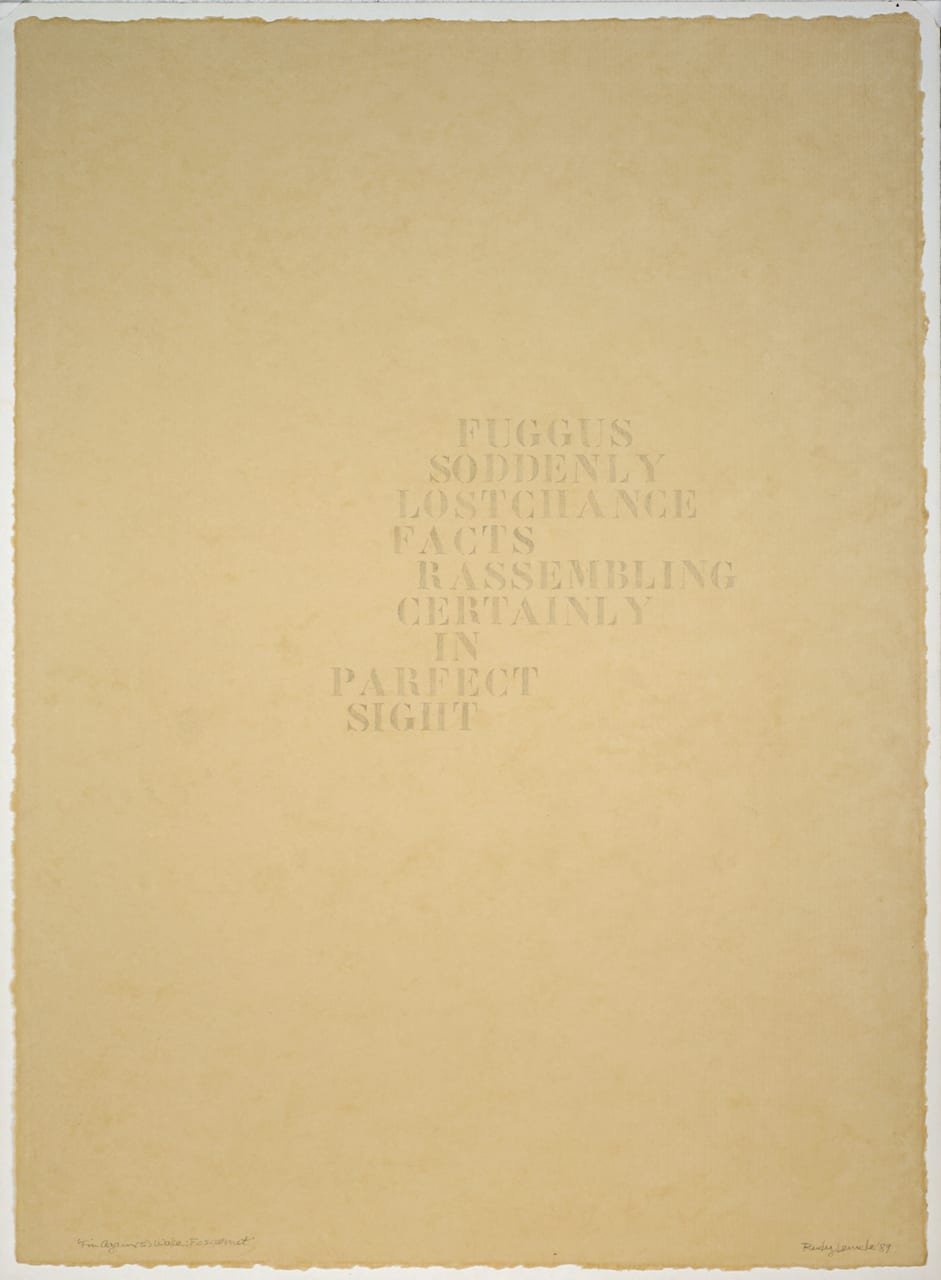

Lemcke: No. I would start by picking the name of a drug that was currently being used to treat HIV/AIDS, which I used as the vertical spine of the poem. Then I would generate a poem that could be read horizontally using Joyce’s words from my notebook. I didn’t use a computer, and it wasn’t really a chance operation, but there was a randomness and improvisational aspect to my process. Just as a performer of a Cage score is often free to create variations within a set of parameters, I produced numerous configurations of words based on a given framework. I wasn’t trying to re-create Cage’s piece but rather a new series of work influenced by Cage’s process. Foscarnet (1989) is the title of the piece from this Fin Again(s) Wake series included in the Art AIDS America exhibition. Foscarnet was a drug used to help treat a form of blindness that affected people with HIV.

Takemoto: Can you read the Foscarnet poem and then talk about your choice of Joyce’s words?

Lemcke: I’ve actually never read the poem out loud for someone or performed it this way. It is more of a thought piece. But I will try: “Fuggus soddenly lostchance facts rassembling certainly in parfect sight.”

Takemoto: How would you “translate” this poem? What thoughts come to mind for you as you read it?

Lemcke: I guess it would read something like: “Focus suddenly, see suddenly, a last chance, possibly a lost chance, these facts, these drugs, resembling certainty, having the promise of a certain cure, uncertainty about this all, my imperfect sight, seen clearly, not clearly at all, imperfect, not certain, in perfect sight.” The words are meant to be seen or felt as conceptual clusters, floating in and out of meaningfulness. I made this drawing using alphabet stencils in very faint graphite on paper. Initially, it just looks like a plain piece of paper on the wall. You can barely see the text. First you see a faint cluster of words on the page that may or may not seem to relate to dying or loss. Slowly the name of the drug becomes legible along the vertical axis, only to retreat back into the cluster of words that provisionally holds its meaning. I was aware of all of the new HIV/AIDS “wonder drugs” that were coming out in the press and on the market at the time. I wanted to make this series of works that gestured toward the range of emotions attached to these drugs: the evasiveness, uncertainty, and precarity of hope for possible “cures” that were coming into sight and then becoming unfocused, lost. These mesostic AIDS poems, which are composed of words about being in the wake of death, also contain within them a way of living with AIDS.

Takemoto: Jacques Derrida writes about the double valence of “pharmakon” as both a poison and a cure. Didn’t many of the early HIV/AIDS drugs also have devastating side effects?

Lemcke: Absolutely. At the beginning of the crisis, many of the drugs and the dosages were completely experimental and so harsh on the system that people wondered which was worse, the disease or the cure.

Takemoto: I am struck by your choice of Foscarnet as a drug that attempts to cure blindness but also as a metaphor for the ability or willingness to see or not see the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Lemcke: Yes, the idea of blindness and recognition resonates in a whole other register in relation to art and politics. In this regard, Fin Again(s) Wake wasn’t just a variation on Cage’s work but also marked my departure from it. While there is a beauty to Cage’s language play and the undecidability of meanings within abstraction, AIDS changed the playing field of queer art for me and for a lot of queer artists. Making art could no longer simply be a linguistic or theoretical experiment. We were now working within social and political systems of power that were literally killing people. I felt the ethical imperative to foreground the reality of the AIDS crisis, to respond to this political moment, and to make art that spoke to its urgency without reducing the message. I wasn’t interested in making agitprop. I was seeking more complicated, multivalent ways of seeing the disease.

Takemoto: You first exhibited this work in 1989. How was it received in light of other artwork about AIDS?

Lemcke: There was a certain moment in the art world during the late 1980s and early 1990s when art about AIDS was very visible and my work was a part of that moment. My model for an AIDS memorial for Harvey Milk Plaza in San Francisco was included in Media to Metaphor, curated by Robert Atkins and Tom Sokolowiski in 1987, and several of my paintings based on the Wizard of Oz were included in Group Material’s AIDS Timeline presented at the Berkeley Art Museum in 1989 and at the 1991 Whitney Biennial. Ironically, the Wizard of Oz paintings, which were the most private and personal works that I made as a gift for a friend who had recently been diagnosed with HIV, became my most public works. There was a timeliness about AIDS artwork that grew out of a sense of urgency as well as feelings of anger, fear, and confusion that cut deeply into the heart of our lives. It was within this framework that much of the iconic work about HIV/AIDS was created. Today, people are looking at the work of that period again, or maybe even discovering it for the first time. It is a painful part of American history that I think a lot of Americans would like to forget. But it’s also a significant part of our queer history and identity, which is exactly why Art AIDS America is such an important exhibition.

Takemoto: Can you talk a bit more about the early days of the epidemic and how it influenced your art?

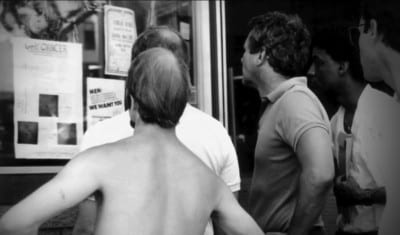

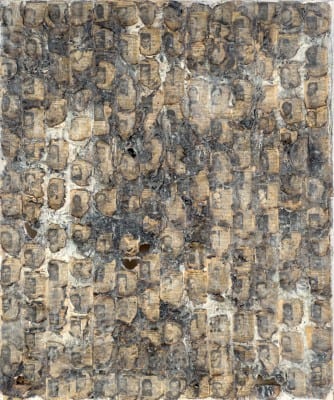

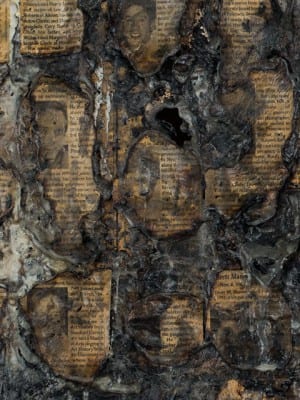

Lemcke: In the early 1980s, when people didn’t even know HIV/AIDS was a virus, it was reported in the news as a gay cancer. In 1982, I remember being in the Castro and seeing an image, taken by local photographer Rink, in the window of Star Pharmacy. It showed a close-up of a Karposi’s sarcoma lesion with a caption about a mysterious cancer that seemed to be affecting gay men. I can’t express to you the sense of panic that was in the air. I distinctly remember that moment, looking at that photo with a group of people on the street. It was terrifying. The mainstream media did its best to keep the general panic directed at gay men, so we had to turn to alternative news sources. In San Francisco, the Bay Area Reporter (B.A.R.) was a local source of news, treatment information, and personals. The obituary section in the back of the paper sometimes went on for several pages. I vividly recall going through this section and cutting out pictures of people I knew or even recognized. I’d say to myself, “Oh, I knew him,” or “That’s the guy from the video store.” I kept these pictures in a box. Years later, in 1995, I was invited to be in a twenty-year retrospective of Southern Exposure Gallery in San Francisco. I was reading Derrida’s book Cinders and thinking about embers, cinders, and ashes. I decided that I wanted to re-create the idea of an obituary section within the exhibition itself to commemorate the losses that occurred during the lifespan of the gallery. Using the pictures I had cut from the B.A.R. obituaries, I lit each one with a match and as it burned I laid the burning ember on the canvas. I put out the flame with dripping beeswax and titanium white oil paint until the ashes were encased and partially erased or obscured. I repeated this process until I used all of the obituaries.

Takemoto: Derrida suggests that “no cinder exists without fire” and that the cinder is both a bodily trace and a reminder of the flame that can never be restored.

Lemcke: That’s exactly what I was getting at. Even now the materials in the painting are still changing with age. As the wax becomes darker, the faces are harder to recognize. I think the fact that the piece is still transforming itself over time makes it more poignant and meaningful.

Takemoto: Your work slows down the grieving process by encasing the portraits in beeswax. We can still see some of the fragments of faces but we are also bearing witness to loss of lives that can never be restored. Are you also engaging with the unrepresentability of loss?

Lemcke: Yes. I was inspired by Jean-Francios Lyotard’s idea of the “immemorial,” which he describes as “that which can never be remembered (represented to consciousness) nor forgotten (consigned to oblivion). It is that which returns uncannily.”1

Takemoto: Immemorial is also the title of a performance piece that you did at the de Young Museum in San Francisco.

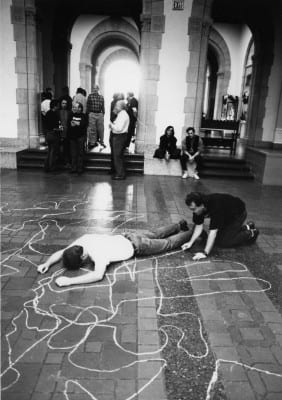

Lemcke: In 1992, I was invited to do a performance at the de Young for Day Without Art, a day of action and mourning responding to the AIDS crisis. There were two parts to Immemorial. The center of the installation was a seventeen-by-seventeen-foot steel garden that I unceremoniously assembled in the museum courtyard. Then I enacted a die-in with de Young staff and visitors. During AIDS protests, people would perform die-ins by falling down on the ground as others drew their outlines in chalk. The trope was taken from police crime scenes and was meant to represent the place where a dead body was found. In the context of an AIDS demonstration, it was a political action that symbolized the lives lost in the epidemic.

Takemoto: Unlike being in the midst of a protest that is moving down the street, your performance enabled people to experience a die-in within a quiet, intimate space where participants and viewers had the opportunity to literally slow down and contemplate their actions. Can you describe the experience?

Lemcke: I remember being completely absorbed in the performance. Most of the time I was just interacting with one other person while viewers watched from the edges. For the people who let me draw the outlines of their bodies, it felt like they were making a personal, sincere statement by collaborating with me—politically and emotionally. The performance continued for several hours until we formed a huge chalk circle of body outlines. This die-in became more symbolic than ones that I had participated in on the street because it was happening as a memorial within this privileged institutional space, rather than in front of the FDA building or a political target. But the action felt just as significant. Ten years after the performance, I made a short experimental documentary in which I juxtaposed footage from Immemorial with my documentation of the ACT UP die-ins taking place on Market Street and Castro in the early 1990s. The video now serves as a both a record of activist history and an art event observed from a distance. Seeing this footage side-by-side reminds us that the missing lives, the absence circumscribed by these bodily traces cannot be restored or resolved—the immemorial.

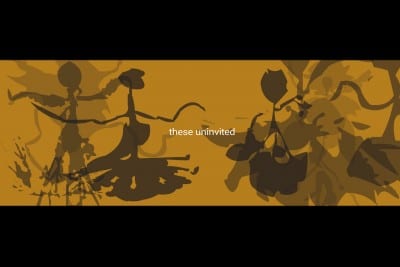

Takemoto: In your video installation The Uninvited, which is also in Art AIDS America, the shadow puppets seem to echo this idea of the missing or absent body, too. How did you develop this piece?

Lemcke: I was reading Julia Kristeva’s The Powers of Horror, and I wanted to do a piece about abjection—the experience of being cast out or the experience of an irreconcilable state that one can’t come to terms with. On the surface, the narrative is about a Vietnam veteran suffering a mental collapse or PTSD. He is homeless and possibly has HIV/AIDS. The specifics of the character’s life and places he describes are purposefully left ambiguous. The piece tries to bring the viewer into his state of irreconcilable dissonance of body, place, and memory. It visually references Balinese shadow-puppet theater. For my version, I created anthropomorphic figures from found materials and showed their shadows performing a type of ceremonial dance while the lines of a poem slowly revealed themselves on the screen. The poem is about the collapse of meaning that comes with the loss of connection to the body and to one’s sense of home. Lines such as “What foreign place is this?” or “My America—Maybe it was something I saw on TV” appear and disappear from the screen. The “sweet, poisonous” music referred to in the poem is echoed in the soundtrack that evokes the nightmare of cultural and physical invasion, and the untranslatable voices and shadows that haunt him. I originally made The Uninvited as an interactive computer-based artwork in 2003. The technology that I used to develop the piece as a CD-ROM using Adobe Flash fell out of fashion, and the format for showing it became technologically obsolete. In 2006 I remade The Uninvited as a single-channel video installation that interacts with the audience in a different way. The projector for the installation is placed on the floor so that the viewers have to walk in front of the projector. In order to see the piece, the viewers also momentarily become one of the shadows on the screen. The Uninvited has had three iterations since I first created it, including a stand-alone single-channel video.

Takemoto: How do you see the relationship between the work you did about AIDS and the work you have done since?

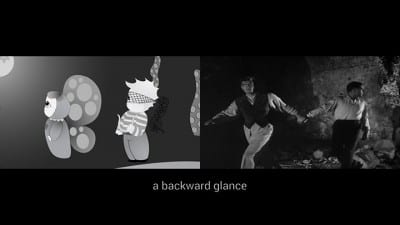

Lemcke: My recent work is a video called (Orpheus) The Poetics of Finitude (2014) screening in June 2015 at Frameline: San Francisco International LGBTQ Film Festival. This experimental video weaves together my anime-style fairytale version of the Orpheus myth with excerpts from Jean Cocteau’s surrealist film Orpheus (1950). In my version of Orpheus, I am foregrounding the idea of human finitude and understanding one’s mortality as the moment of individuation and coming into our unique awareness of the self and identity. This is a slightly different reading than Cocteau’s, in which he is trying to grasp the source or meaning of the poetic. For him the poetic is understood in the context of transgression in terms of desire and death. I don’t think that either of these interpretations elides the other. But by placing these perspectives side-by-side, my video puts both readings of Orpheus into play. Together they offer a reckoning with death—with finitude—that brings with it a type of forgetfulness; and it is this hidden/revealed relation to death that is the source of the poetic and one’s authentic self.

Getting back to your question, what I now understand about my post-AIDS work is that I am still dealing with and will probably continue dealing with issues of political and personal rupture, memory, loss, and, to be honest, a certain melancholy that comes from living so “close to the knife” for so many years. The ghosts of the friends who have passed away still haunt me—not in a paralyzing way—but I feel their absence. Sometimes when I walk down Castro Street or see men in line for prescriptions at Walgreens or see someone that I knew from back in the day, it triggers a memory and the circumstances surrounding that moment in time. As individuals and as a community we can move on after trauma, even after a crisis that has had a defining impact on our identity. But it’s not forgetting or turning away that makes this movement possible, quite the opposite. It is precisely in that looking back, in the joyful preservation of what we have come to value from the past and a willingness to consider new ways of thinking and seeing, that the horizon of future worlds becomes visible.

Tina Takemoto is an artist and associate professor of visual studies at California College of the Arts. Her essays appear in Afterimage, GLQ, Performance Research, Radical Teacher, Theatre Survey, and Women and Performance. Takemoto has received grants from Art Matters, James Irvine Foundation, and San Francisco Arts Commission. She is board president of the Queer Cultural Center in San Francisco.

Rudy Lemcke is a new media artist who lives and works in San Francisco. His artwork has exhibited internationally in galleries and museums including Modernism, Inc., San Francisco; Whitney Museum of American Art; Berkeley Art Museum; and de Young Museum. He is a founding member of the Queer Cultural Center and co-curator of Queer Conversations on Culture and the Arts.

- Bill Readings, Introducing Lyotard: Art and Politics (London; New York: Routledge, 1991) ↩