Jannis Kounellis in Six Acts. Exhibition curated by Vincenzo de Bellis and Kit Hammonds with William Hernández Luege. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, October 14, 2022–February 26, 2023; Museo Jumex, Mexico City, April 1–September 17, 2023.

Vincenzo de Bellis, ed. Jannis Kounellis in Six Acts. Exh. cat. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2022. 432 pp.; 273 b/w ills. $55.00 paper

The Walker Art Center, in collaboration with Museo Jumex, presents an ambitious and long-awaited homage to Greek-born Italian artist Jannis Kounellis (1936–2017). As highlighted by the curator Vincenzo de Bellis (22), the Minneapolis museum boasts a historically close relationship with postwar Italian art: in 1966 it hosted the first solo shows in the United States of Lucio Fontana and Michelangelo Pistoletto, followed by one devoted to Mario Merz in 1972. In addition to collecting several works by artists associated with the Arte Povera group, including two by Kounellis, in 2001 the Walker organized the major exhibition Zero to Infinity: Arte Povera, 1962–1972, a joint collaboration with Tate Modern. In the late 1960s, artist Pietro Consagra and art critic and (later) feminist activist Carla Lonzi spent some months in Minneapolis: the former as a visiting professor of sculpture at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the latter editing the taped conversations with artists that would be published in her seminal book Autoritratto (Self-Portrait).1 Kounellis was among them—his recorded voice reverberated within the walls of Lonzi’s house, a few steps away from the Walker, where now it is his works that take up the task of expressing the essence of his practice.

The exhibition, spanning more than five decades of artistic production, unfolds through six thematic cores—Language, Journey, Fragments, Natural Elements, Musicality, and Reprise—corresponding to recurring themes within Kounellis’s oeuvre. They are referred to as acts, an homage to the artist’s engagement with theatre and theatricality. The first room is the only one that mostly corresponds to a specific chronological period, that of the early 1960s, while remaining coherent in terms of medium and theme. Painterly explorations of typographical characters, inspired by visual elements of the Roman urban landscape, float on white canvases in the form of letters, numbers, and signs, variously arranged according to an internal dynamism. Kounellis moved to Italy in 1956 from his native Greece to enroll in the Fine Arts Academy in Rome, where he studied with Italian artist Toti Scialoja and began presenting his work alongside fellow painters based in the capital, including Cy Twombly and Mario Schifano. The works in the first room illustrate this early phase of his practice, when the letters of the Latin alphabet appeared, to a Greek native speaker, as unfamiliar and cryptic signs in the everyday visual experience of the Roman streets, and when the artist engaged with painting as traditionally intended (251). In the following decades, the artist would never touch a brush again—instead privileging sculpture, installation, and performance—yet he would continue to define himself as a painter with uncompromising firmness: “I am a painter, and I assert my initiation in painting. Because painting is the construction of images and doesn’t indicate a manner or, even less, a technique” (223). His engagement with materiality, which would be explored through natural and industrial elements in the following decades, emerges here in its initial phase: the paint is porous and glossy, layered and dripping, its movement crystallized in a precise moment in time.

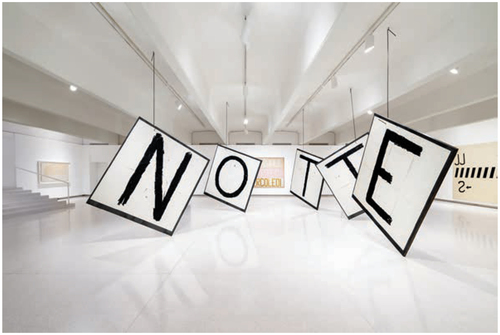

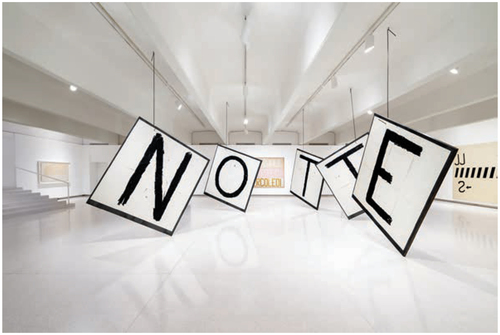

Dominating the first room in a high-impact display is the monumental Untitled (1996), composed of letters painted on paper sheets attached to five steel plates. Arranged in a semicircle to form the Italian word notte (night), the work demonstrates Kounellis’s enduring interest in language and signs. One is left to wonder how such colossal metal slabs could appear so effortlessly suspended in the exhibition space, with only one edge touching the ground and another connected to the ceiling through a metal rod. The hook is the device that allows the precarious yet perfect balance to be maintained; it is also a recurring motif that runs through the artist’s oeuvre both in three-dimensional and pictorial form, as exemplified by the works exhibited in the first room. In one, Untitled (1960–98), portions of early paintings are placed on a steel plate, partially covered by a rigid fabric whose folds are secured by metal hooks, by which a burlap sack is also attached. In the surrounding paintings, the letter “J” evokes the shape of the hook, repeated according to a compositional rhythm that reiterates the artist’s initial.

The trope of the journey, a metaphor of earthly existence and artistic research, is explored in the following section. Biographical elements are often taken into account when addressing the artist’s relationship to travel, movement, and the sea: Kounellis was born in Piraeus, the port of Athens, to a father who was a naval engineer. Boats and vessels point not only to personal and familial histories, however, but also to universal notions of migration and displacement. Their wooden and metallic fragments become, in the artist’s oeuvre, monuments to the material memory of the sea and the trade that has historically connected the shores of different countries and continents, facilitating cultural dialogue. Wooden planks, rusty nails, anchors, fishing nets, burlap sacks—even a model train—are sculptural manifestations of the dynamics of motion and exchange entailed in any journey by sea and by land. Kounellis identified with Homer’s Odysseus and James Joyce’s Ulysses, but he was bound to wander in perpetual exile, never returning to his homeland.

In this room, as in the following ones, works from different decades are placed in conversation with one another, a curatorial strategy that brings to light Kounellis’s lifelong investigation of specific ideas and preoccupations. This dialogic formulation of the exhibition is activated not only through a chronological overlapping, but also through a thematic one. Despite the division into six topics, there is a cross-pollination at play within the different chapters through which Kounellis’s oeuvre is read, a structure that, as a narrative device, is based on flashbacks and anticipations. The fragment, for instance, despite being explored in a specific section, can be considered more broadly as a concept that permeates the entire show, embodied in shreds of language and remains of ships, skeins of wool, and pieces of classical sculpture. These are presented in the third room of the exhibition (Fragments) in the form of plaster heads displayed on metal shelves (Untitled, 1979), or as sectioned parts of sculptural replicas on a table (Untitled, 1974), while others appear among stone slabs accumulated in a recess carved out of the wall (Untitled, 1982). Originally assembled in a doorway at the Staatliche Kunsthalle in Baden-Baden, Germany, the work is now part of the collection of the Walker, where it has been reinstalled and recreated with Feather River travertine sourced from a Minnesota quarry. The fragment was for Kounellis—who had personally experienced both the Second World War and, immediately after, the Greek Civil War—the expression of a postwar existential condition that he described as tragically characterized by a “loss of wholeness” (190).

In the section Natural Elements, Kounellis’s investigation of nature is examined both in figurative terms and in material ones. Paintings with graphic outlines of fabric, wooden, and painted flowers (all Untitled, 1966–67) encircle a bed frame with raw wool (Untitled, 1969), while coal and sulfur appear disposed in burlap sacks and on metal scales (Untitled, 1968; Untitled, 1992). Arranged vertically and connected to one another through a thin hook, the artist more often employed scales such as these to display pyramid-shaped piles of ground coffee, as illustrated by another work on display (Untitled, 1969). This urge to sort matter and granular substances into measurable units can be seen as an attempt, on his part, to give the natural world a human order. Fire is another natural element that Kounellis sought to tame and channel, as open flames or propane gas. In the Walker exhibition, it is presented through the form of traces, such as in Untitled (1984), where black scars of soot left on a white wall by a burning flame allude to a form of painting with living matter that recreates the shades and the chromatic intensity of the traditional medium, adding a sense of ephemerality and evoking a performative dimension. Empty metal shelves do not provide space for the display of sculptural items, instead framing and drawing attention to the missing element—fire—from which the marks originated. The legacy of painterly tradition is openly acknowledged in the work through a black square, a direct reference to Kazimir Malevich.

One of the highlights of the exhibition is Untitled (1972): originally presented at Sonnabend Gallery in New York on the occasion of Kounellis’s first solo show in the United States in 1972, it is displayed at the Walker for the first time in fifty years. Two human scale metal boxes, placed next to one another, constitute the stage for a musical performance. In one box, partially covered by a curtain, Kounellis stood motionless, impersonating the Greek god Apollo through the plaster mask that he was holding; in the other, American flutist Jon Gibson played a short excerpt by Mozart on repeat. The musical fragment engages with a circular and recurring temporality that emphasizes the ephemeral and fleeting nature of sound. The artist adopted the divine persona in several performances, including in a video presented in the exhibition (Untitled, 1973), in which he similarly appears impersonating Apollo while holding an oil lamp, a reference to the Enlightenment. Produced by the Florence-based experimental video art studio art/tapes/22, Untitled emulates, through its frontal perspective and the fixity of the image, a painting. Or rather, a living painting, following the tradition of the tableau vivant, as examined in the catalogue by de Bellis who underlines how this device “cites the past but also absorbs it into the present” (46).

The work, now part of the Sonnabend Collection Foundation, was reenacted live by two performers only on the opening night, remaining empty and silent for the rest of the exhibition. This curatorial choice was in contrast with previous presentations of Kounellis’s actions within an exhibition setting, such that as at Fondazione Prada (Venice, 2019) and the Museum of Modern Art (New York, 2013), where performances were scheduled at specific moments, as well as for the show Entrare nell’opera. Processes and Performative Attitudes in Arte Povera, which was specifically devoted to live actions.2 Though it might appear a missed opportunity, the decision to not engage with Kounellis’s exploration of performance is related to the artist’s passing in 2017, an unforeseen event that led de Bellis to opt for a more conventional retrospective reading, thus putting aside the original plan which envisioned a show specifically focused on live actions (38). A similar curatorial approach was adopted in Jannis Kounellis: A Retrospective, held at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in 1986, the last display of the artist’s oeuvre in the United States before the exhibition at the Walker, and the recent solo show at Fondazione Prada in 2019.3 The exhibition in Minneapolis largely differs, however, from both of these precedents. Despite presenting some works previously included in the 1986 show, Jannis Kounellis in Six Acts does not expand throughout the urban fabric of the city using large scale installations as occurred in Chicago, while in comparison to the show in Venice, the one at the Walker includes different and lesser-known works that are more ambitious in scale, as well as deeply connected to the country in which they are displayed.

Kounellis’s relationship with the United States emerges throughout the show in historical, personal, conceptual, and material terms. In addition to including some seminal works that marked the American public’s first encounter with the artist and his oeuvre, the exhibition reveals the United States as a site of personal ties and memories. His father’s address in New York is stenciled on a white canvas (Untitled, 1963), a work exhibited here for the first time, as if it were the envelope of a letter never delivered. Other connections shed light on Kounellis’s encounters with the city of New York. Glasses of various shapes and dimensions, arranged on metal shelves attached to steel plates (Untitled, 2013), were purchased in a Hasidic-owned glassware store in Brooklyn (306); the group of tintype photographs included in Manifesto per un teatro utopico (Manifesto for a Utopian Theatre, 1973), displayed along with a yellow canvas and a sewing machine, were sourced from a New York flea market. These objects are materially permeated with personal memories of unknown people from distant places in an indefinite past. As manmade artifacts that have outlived time and their own creators, as well as the people who used and cherished these objects during their lives, they represent the paradox of the human condition, as well as the poetic essence of the everyday and the mundane.

In the insightful essay published in the exhibition catalogue, Ara H. Merjian examines the legacy of Surrealism in Kounellis’s oeuvre, one aspect of which is traceable in the removal of objects from their original contexts and in their unexpected juxtapositions, a strategy that creates disturbing, yet profoundly lyrical semantic associations. The publication also includes important contributions by Claire Gilman on the “melodrama of painting” in Kounellis’s oeuvre; by curator Kit Hammonds, who delves into the artist’s conception of the exhibition space as a theatrical cavity and his opposition to American Minimalism; and de Bellis, who traces the origins of the retrospective and its conceptual core. These innovative and profound critical analyses of the artist’s work are presented together with a detailed and informative account of Kounellis’s live actions between 1960 and 2016 compiled by Michelle Coudray and de Bellis, and a section devoted to his writings selected by Michelle Coudray and edited by William Hernández Luege.

Jannis Kounellis in Six Acts offers an immersive and sensorial experience of the artist’s visionary oeuvre, unveiling its dramatic, theatrical, and poetic essence in an epic journey of an existential and artistic nature. In the last room, a group of variously colored, monumental sails (Untitled, 1993) welcome the visitor to the final act of the show. They have crossed the seas and defied the winds, and now are resting suspended, in a sculptural stillness reminiscent of Caravaggio’s dramatic renditions of drapery. Passing by them, one has the impression that they progressively descend, one after another, like stage curtains closing at the end of a theatre show. It is the end of a journey that inspires an elegiac meditation on the sense of no return, the same that had accompanied Kounellis throughout his entire artistic life, and even beyond.

Dr. Roberta Minnucci is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History in Rome. After gaining her PhD from the University of Nottingham with a thesis which examined Arte Povera’s engagement with cultural memory, she was a Rome Award holder at the British School at Rome and the 2022–23 Scholar-in-Residence at Magazzino Italian Art (Cold Spring, New York). Her research has been supported by the Getty Foundation, the Association for Art History, the Association for the Study of Modern Italy, the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and the Ragusa Foundation for the Humanities. She has gained curatorial and research experience at different institutions, including Tate Modern, Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, Christie’s, Southampton City Art Gallery, Castello di Rivoli, and Museo Fondazione Pino Pascali.

- Carla Lonzi, Autoritratto: Accardi, Alviani Castellani, Consagra, Fabro, Fontana, Kounellis, Nigro, Paolini, Pascali, Rotella, Scarpitta, Turcato, Twombly (Bari: De Donato, 1969). The book has been recently translated into English: Carla Lonzi, Self-Portrait, trans. Allison Grimaldi Donahue (Winstone: Divided Publishing, 2021). ↩

- Jannis Kounellis, exhibition curated by Germano Celant, Venice: Fondazione Prada, May 11–November 24, 2019; Ileana Sonnabend: Ambassador for the New, exhibition cocurated by Ann Temkin and Claire Lehmann, New York: Museum of Modern Art, December 21, 2013–April 21, 2014; Entrare nell’opera: Processes and Performative Attitudes in Arte Povera, exhibition cocurated by Christiane Meyer-Stoll, Nike Bätzner, Maddalena Disch and Valentina Pero, Vaduz: Liechtenstein Museum of Fine Arts, June 7–September 1, 2019, Saint-Étienne: Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, November 30, 2019–May 3, 2020. ↩

- Jannis Kounellis: A Retrospective, Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art, October 18, 1986–January 4, 1987. ↩