The Feminist Interview Project, organized by Katherine Guinness and Jocelyn Marshall on behalf of CAA’s Committee for Women in the Arts, examines the practices of feminism by interviewing a range of scholars and artists, preserving oral histories while expanding the boundaries of what might be considered feminist. Throughout its interviews, this project reimagines the possibilities of feminist practice and feminist futures.

For our ongoing collaboration with Art Journal Open, the Feminist Interview Project is excited to present artist Michal Heiman in conversation with Gil Z. Hochberg, Ransford Professor of Hebrew and Visual Studies, Comparative Literature, and Middle East Studies at Columbia University, and the current Chair of the department of Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies. The two met for conversations over Zoom from September 2–5, 2023.

Gil Z. Hochberg: Michal, it is great to have this extended dialogue with you. You have been so generous with your time, so thank you. I wish I could find a way to include everything we talked about over the course of sixteen-plus hours!) in this printed version, but that would require a book-length publication. Following the format of these interviews, I am going to open with the question I think you were least excited about: “What is Feminism for you?”

Michal Heiman: This is the most difficult question for me. It took a lot of back and forth between us for me to come up with an answer I felt comfortable with and is the outcome of our ongoing dialogue, so it is yours as much as it is mine. I find it hard—impossible, actually—to nail down the definition of feminism. What I am going to provide is not a definition. It is my personal account, which is a feminist act. For me, feminism started as the culmination of my childhood echoes and things I witnessed both in and outside of the home. Some of these were very painful things to witness. A major one, takes me back to age six. I am in my room getting my backpack ready for school. I hear yelling. Familiar yelling. I see a beautiful light coming in through my parents’ room, I see their unmade bed, and my mom standing frozen by the bed. She is crying. I approach her and say: “Come on, pack, take a suitcase, take David (my younger brother) and take me. Let’s get out of here, let’s leave!” My mom looks at me and says: “Go where, Michali? I have no money, no profession, no work, and we’ll have nowhere to live. Everyone will turn against me.” The last part of her sentence left a sting. I remember how softly she said my name, adding an “i” at the end to make it even softer. For me this was and remains a primary scene (although there are many others) and my entrance into feminism. Not as an ideology, but as a painful realization, voiced and verbalized to me, a little girl, like a lesson. I learned my lesson. I learned my father imprisoned my mother.

GH: This is powerful. And painful. Lessons “put us in our place.”

MH: Yes. A film of mine, from 2020, about the American writer Elizabeth Parsons Ware Packard (1816–1897), touches on these fears and violence. Her husband claimed she was insane and locked her up for more than three years. I return to questions about women’s imprisonment, immobility, and how they are controlled by their so-called saviors: husbands, lecturers, therapists, academic and psychiatric institutes. Most of my work is about consistent and often silentviolence that shapes the lives of so many women. Perhaps many share a similar primal scene: dad yelling, mom frozen. This scene lives in me. We never left the house. My dad forgot about his violence a minute later and I, like her, accepted the situation. We surrendered. A total defeat. So, I suppose feminism for me is, to a great extent, awareness to violence that takes place in the most intimate places.

GH: Yes, I recognize this in your works, which are so intimate and often expose no visible violence. Just the aftermath of violence, or the preceding scene. There is something so powerful in your work and in the provocative questions that often accompany your images.

MH: Yes, listening is a significant part of my work. In many cases I spend hours sitting in the museum or the gallery space, inviting people to talk to me. But truly, with women, many times, it is silence one needs to listen to. Silence and body gestures. You know, often people with authority, therapists, family, etc., will say that victims of sexual trauma have “no coherent language.” But survivors of sexual trauma do have a language: a perfectly reflective language made of silence, ambiguity, body aches, memory loss, confusion, headaches. Is there a clearer more reflective language than this? What we are still lacking is the ability to listen to this language . . . there is not enough listening. So often, the body speaks and hardly anyone listens. Not in all the psychoanalytic clinics, not in court, not at home. It is the “unrepresentable.” My work fights against this patriarchal paradigm. It is a repeated attempt, one I will never let go of, to do away with this concept of “unrepresentable” and “untreatable.”

GH: Your work is about intersections of desire, fear, dreams, fantasy, attraction, and repulsion. These are obviously concerns that are at the heart of all psychoanalytic theories. You are a member of the Tel Aviv Institute for Contemporary Psychoanalysis. Still, you are openly critical of psychoanalysis as is your work. Can you talk about this close and critical relationship your art has with psychoanalysis as a theory and a therapeutic method?

MH: I have so much to say about this. My work is tightly bound with psychoanalysis, so it is hard to decide where to begin [laughing]. Psychoanalysis fixates on questions of responsibility, seduction, and desire, and forces the reader or the patient to confront the possibility that what she thinks happened or the wrong she feels in her body, maybe never happened. I work closely with texts of psychoanalysts I appreciate, whose work shares a connection to the arts and the visual: [Donald] Winnicott, [Wilfred] Bion, and the more current Michael Aigen. And, of course, Freud. I learned a lot from them and from my own therapist about the relational dimension of all human interactions. And I would add that psychoanalysis is very important for me personally; it helped me a lot. On a theoretical level, the questions psychoanalysis asks are the questions that have interested me for many years, long before I knew the lexicon: regression, oppression, transference, projection. Psychoanalysis gave me words and terms for some of my work, what I was already doing.

GH: I once wrote an essay about theory as a prison-house for women. Do you feel that way about psychoanalysis?

MH: I think the camera especially can help highlight the performative aspects of what it means to be in relation to another and to build a community. Looking, being seen, hiding—none of these are static positions. The camera helps us recognize them as dynamic. Cameras operate as a time machine and are great devices to infiltrate. As for theory, I think any general overarching argumentation has serious limitations. When I give performance-lectures at different institutes including psychoanalytical institutions, I try to step away from theory and challenge its authority and coherence. We know that theories almost always lead back to a father figure—fathers of psychoanalysis (yes, and Melanie Klein), father of this, father of that. I’m not saying theories have no importance, but they must be constantly revisited, challenged, and diversified from the point of view of those rendered mute. I think that the reason why I read psychoanalysts, is that I am interested in the case studies; they remind me of romance novels. Filled with camouflage, obfuscation, and erasure, they oscillate between reality and fiction.

GH: You often invent and use your own terms: “savior-attacker,” “scanogram” (the connection between scanning, photography, and video you use to activate photographs), “chronic visual harassment.” Is this part of your intervention, or as you term it, “infiltration?”

HM: I consider my work to be that of an (art)ivist. This involves the practice of translation, making connections, listening, looking, digging through the trash, archiving that which is considered unworthy, creating a language for the muted. Terms I coined and use throughout my work, including chronic visual harassment and the savior-attacker, come from my childhood, later memories, and instances in which I feel other women calling me. Women from the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries asking me to join them in the asylums or the archives in which they are trapped, to witness them, to believe their stories. The term savior–attacker, for example, comes from a specific personal experience I had when I was probably four: the one that attacked me, by throwing a stone directly at my eye, was the same one that “saved” me later. This experience of being abused and harmed and then saved by my abuser-attacker left me suspicious of “saviors.” The term points at the fact that in many cases, only the act of rescue is visible, while the act of abuse remains secretive.

Those saviors-attackers are immortalized in the space of the family photo album. We find so many savior-attackers in the family album. We find them also in the press, in the museum, in the annals of art history, as well as in the pages of psychoanalysis.

GH: Let’s talk about your series of works, the Michal Heiman Tests, especially since you are clearly referring to psychoanalysis but also overtly critical of it as a therapeutic modality.

MH: Yes. The Michal Heiman Tests (M.H.T.’s) started with my discovery of the creators of diagnostic tests in the twentieth century. I was stunned to discover these tests, and I now own a collection of them in my archive. What fascinated me was their performative aspect—everything is so measured. And the manuals for these tests seem like works of art or installations. I was inspired, and also annoyed, as this battery of tests is the holy of holies, meant to be only for experts.

The tests are meant to raise questions about visibility and invisibility, obscurity, shame, responsibility, accountability, and manipulation. I use the diagnostic modality of tests to generate dialogue, not to label and confine (which is what many of the original psychological tests often do). For the first two tests I used photographs from different family albums, including my own, as well as from public archives that I collected over the years.

The first test, M.H.T. No. 1, offers a deconstruction of the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT). I replaced the TAT’s visual materials and manual with my own. For three months, people were welcomed by examiners who recorded their conversations. The idea was to challenge the limited gender assumptions inherent to the TAT and deconstruct the space of the museum into a place of exchange, listening, witnessing, and dialogue. The second M.H.T. test, called My Mother-in-Law: A Test for Women Only was curated by Dominique Abensour and first reenacted at Le Quartier Center for Contemporary Art in Quimper, France in 1998. The setting mimicked the traditional Freudian prescription for psychoanalysis, with the examined woman lying on a sofa and the examiner sitting behind her. Both M.H.T. No. 1 and No. 2 were designed by Michael Gordon, and the manuals were written by Ariella Azoulay.

The third M.H.T. is called M.H.T No. 3: What’s on Your Mind? It was presented in a theater rather than a museum and included a big construction with a court stenographer writing everything. The test procedure requested that six volunteers—lying on couches and without being able to see each other—along with a mediator, attempt to reach a unanimous description of a short film they viewed. The request to agree was challenging and ended in amazing sessions, even sometimes violence. Especially from the audience.

The fourth M.H.T. is most relevant to the term “Chronic Visual Harassment.” It’s based on the Szondi Test, developed by the Jewish-Hungarian psychiatrist Leopold Szondi. He invented a diagnostic tool in the hope that it would reveal what he called “the family subliminal.” He believed photography had the power to ignite reactions that expose the hidden forces behind human behavior and experience, and that an encounter with a photographic portrait could reveal the true nature of the subconscious. I share something in this; I think a meeting with a photographed portrait can activate the unconscious in ways no discourse can. That is what happened to me when I found myself in a portrait of a woman from the nineteenth-century asylum.

GH: Can you explain what that means—you have found your own image in the archive in a portrait of a woman from the nineteenth century?

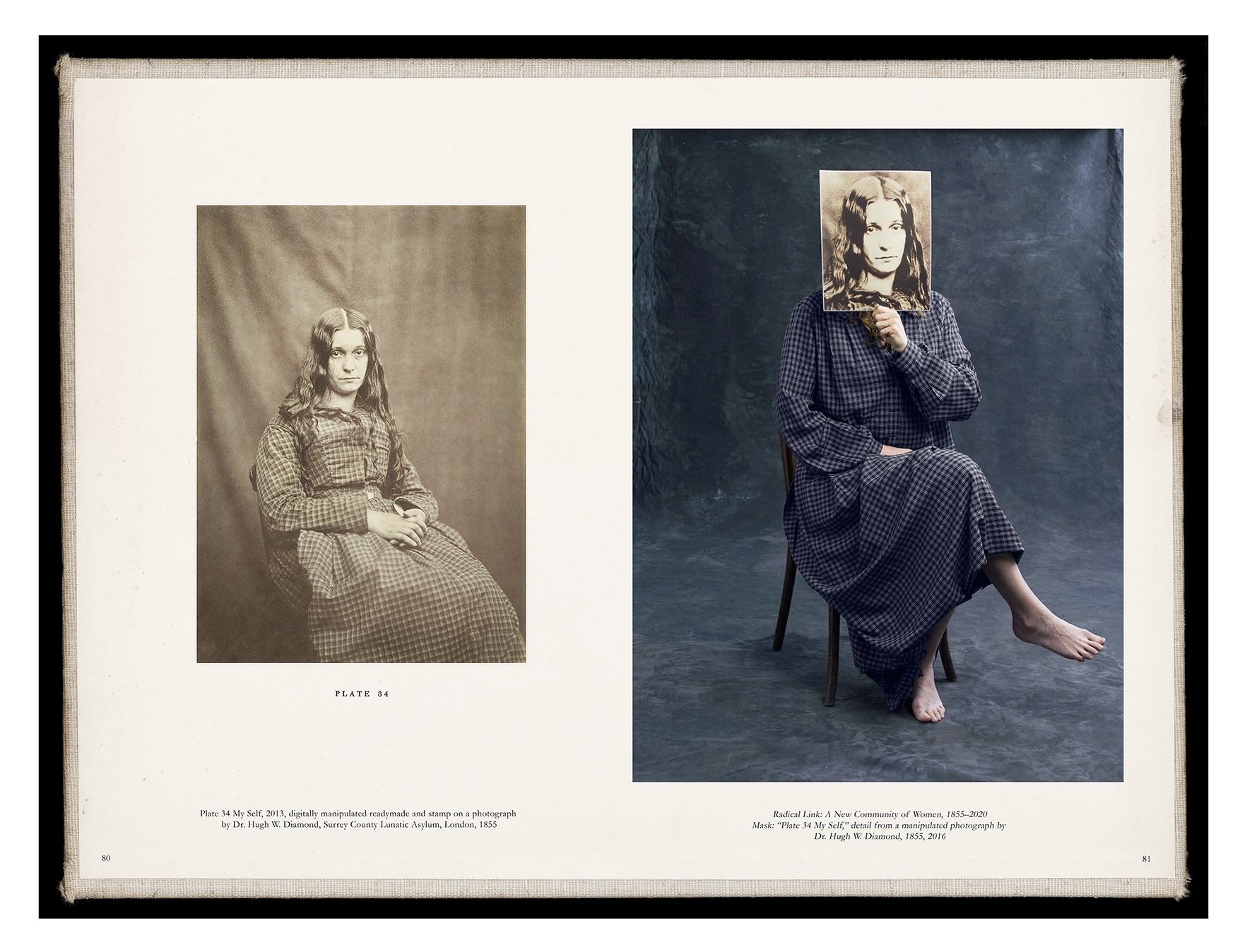

MH: I found myself in image thirty-four in The Face of Madness: Hugh W. Diamond and the Origin of Psychiatric Photography, a great discovery and work by the editor Sander L. Gilman. Like most of his generation, Dr. Diamond, who worked at the Surrey County Asylum in London, was controversial, but also an amateur photographer, collector, and pioneer in believing that the camera could cure his patients. Of course, I know the photo was taken over 150 years ago. Still, I am saying, I found myself in that image. Or better yet, that photo found me. I didn’t look for this encounter. It found me, as did questions about my right to return as a photograph to my image in a photograph from the nineteenth century.

Everyone has “the right to return.” I am using this loaded term, which Palestinians use to demand their rightful return to their lands in Palestine, on purpose. It is a basic right that everyone should have. We live amid crises of displacement and flows of refugees, intransigent nationalism, people moving across borders and identities, fleeing, going elsewhere, and yet wishing to return; always wishing to return. And the right of return stands at the heart of political debates in my part of the world.

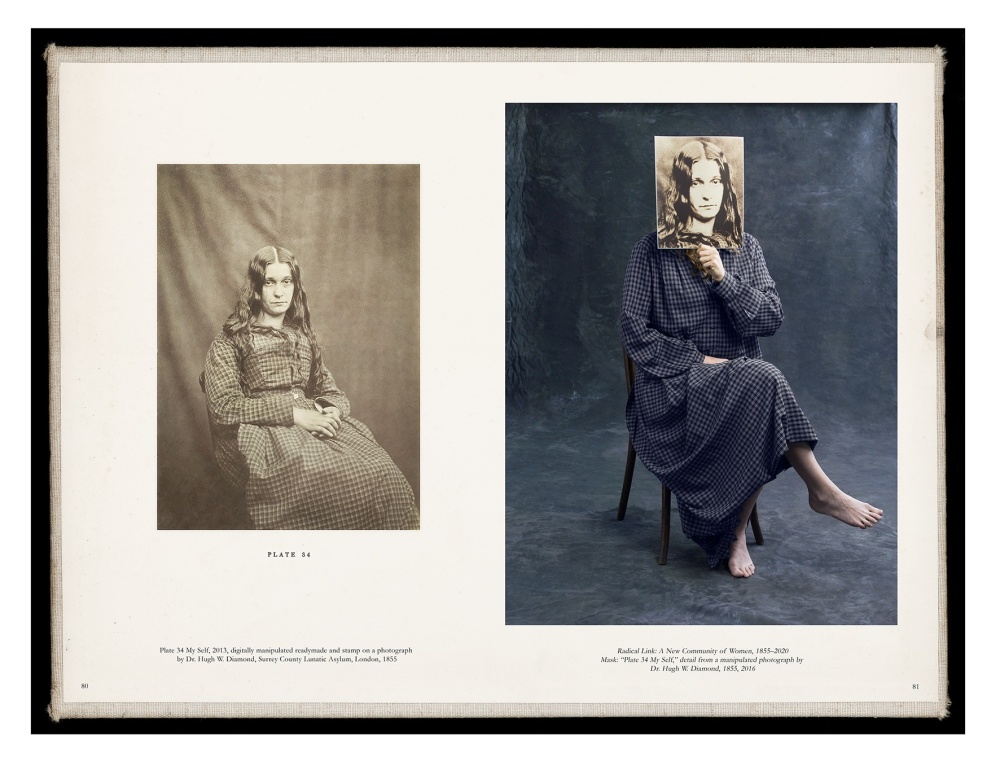

Will we be able to forge a path to a “return”? This has been the continuous focus of my project during the last few years, a proposal for a new model of “returns” and a building of a new community (A New Community of Women, 1855–2023). This project asks, among other things, questions on strategies of returns and resistance.

My personal right to return is to the image that calls me from the nineteenth century. But to understand what I mean by this return I need to explain some things about what I think art can do. Psychoanalysts try to connect to their patients and through this connection bring them back to earlier connections and even radical merging, to revive the fantastic original inseparability (caregiver-baby). One of the problems I have with this is that the process doesn’t give enough tools for separation. Connecting to another took me a long time to understand, it is not losing oneself in a fantasy of oneness.

When I was fifteen and a half I encountered an image of a face in a wardrobe, an image that was forced upon me. Finding it impossible to look at, I quickly turned my eyes away, and in doing so my gaze came upon a mirror. In it I saw, along with the face, a reflection of myself. The reflection doubled the master bedroom, visible through an open door behind me, creating a space so much bigger than the injuring one I was occupying. This encounter has since been at the heart of much of my work, a moment of origin from which my art stems and to which it perpetually returns. The mirror, I realized, saved my life and became a passage that allowed me to be transported through it to what I now know was a photographic studio in the Surrey County Asylum in London, in the year 1855, Plate 34. Twenty-five years later my shaken gaze time traveled to the San Servolo Asylum in Venice, Italy, where it landed on the face of Maria Dominica D’Alberto, a woman hospitalized and described as melancholic, in a photograph taken on January 20, 1880.

GH: Do you feel people are able to understand or relate to this? I am trying to get a better sense of what you mean, since I assume you’re not just referring to a visual link with her (in the photographs)?

MH: It’s still very sensitive. Don’t say “her” please; these images are no longer separable from me. I understand your question, you are afraid for me, and for the readers here, but I know that people understand so much, more than they or you may realize. I have a series of videos called Can you help me? documenting people advising me on how to “return” or merge with the two plates. Besides, the strategy of intervening in existing spaces and archives as well as historical events isn’t new to my practice. All of work is about breaking certain links and creating other ones instead. More emancipatory ones.

Entering photographs, videos, sounds, and archival materials is very demanding and requires courage. Inhabiting the body of another in an image, breathing her breath, trying to revive her, it can be painful. Finding access to another time, to different eras, photographs of women in asylums, women deprived of their human rights, may only be possible through those actions, but it is costly. My body is aware of this. So is my mind. Every resurrection between two subjects may become a radical linking and can result in injury. I try not to go alone; I take others with me on these journeys. Many came with me, some from the present, some from the past: Ariella Azoulay, Virginia Woolf, my daughter Emily, the artist Roee Rosen, my dear friend Noureldin Musa, and many others.

GH: Going back to testing—what is it about the testing that is so appealing to you? And, what about the psychoanalytic therapeutic scene do you find worthy of artistic investigation—both as an act of mimicry and critical revisiting?

MH: This again becomes personal. In 1985 I went to see I psychologist. I was looking for someone to talk to. Instead, I was presented with a battery of tests. Later I learned these are canonical tests, but at the time I thought these were strange disturbing visual symbols, and the ceremony felt like a mysterious ritual, a rite of passage, and cultish. The therapist kept pulling out one image at a time from a box, asking me to tell stories about them. Some of the images seemed very violent and I felt trapped. I was asked to take part in a hermeneutical process I wasn’t sure I wanted to participate in. I felt I was subjected to the demonic need of the analyst to uncover my secrets. Yet, as a visual person who works with images, when asked to talk about images, I felt compelled to do so. Not only did I have the urge to engage in interpretation, the visuality of the test itself (the box, the plates, the setting) and the ritual filled me with curiosity. The therapist asked me to draw a man, a woman, a tree, and myself. The artist in me rebelled. I immediately sheltered myself by knowing it can be great for my next works [laughing]. I knew that every choice, every interpretation I made would be open to scrutiny and critical analysis. Still, I wanted to see more images coming out of her boxes. (I found out later she was using the TAT.) This feeling was so intense—a combination of attraction and repulsion to each image. I continued to work with this therapist and years into my analysis, accompanied by my ongoing research, collecting, and archiving, I felt ready to “test” the analysis itself, to interrogate the rules involved in these tests. So, I armed myself with my own archive, made of my earlier collection of photographs from Photographers Unknown. I am sure you have a lot of experience with that; how people create archives using students, artists, writers, patients—those whose work is eliminated and made invisible under the regime of power and citation politics.

I am very worried of those who hold positions involving interpretation and selection: critics, editors, curators, museum directors, collectors, politicians, therapists, imperialist archivists, and visual culture experts—anyone who decides what we should see, where, and why, what should be remembered and forgotten, preserved, moved, destroyed. I wanted always, even if subconsciously, even as a child, to draw my own narrative.

GH: Archives, archiving, and collecting are so central to your work. Both in terms of aesthetics and method; you visit archives, work with and reproduce archival material, collect photographs. What is the archive for you?

MH: I am very worried of those who hold positions involving interpretation and selection: critics, editors, curators, museum directors, collectors, politicians, therapists, imperialist archivists, and visual culture experts—anyone who decides what we should see, where, and why, what should be remembered and forgotten, preserved, moved, destroyed. I wanted always, even if subconsciously, even as a child, to draw my own narrative.

I started my archive of photographs when I began photography school in my early twenties. During the first week of school, they took us to see how to print photographs. While everyone was busy with the printer, I was interested in two large trash cans. I looked inside and found lots of photographs struck through with black marker. I asked myself, “What are they throwing away and why?” I grabbed as many of the trashed photos as I could and hid them under my jacket. The guard caught me, I managed to keep some. This was the birth of my passionate relationship with photography and the archive. I have always been interested in the process of elimination: what stays and what goes. So, it was only natural that one of my installations, Photo Rape (curated by Galia Yahav) ended up using some of these photographs.

All archives offer traces and hints. I can find names, images, but not narratives. One needs to create those, which I do through photographs and stories of women that find me, and spending lots of time in libraries researching those images. My asylum project started when I was collecting my Lying Women. I am not “visiting the past,” or “researching the archive.” I am visiting myself and my community and that is never a past. The archives I visit are just part of the archives I create, together with others. Always with others. My archive is communal and always expanding.

I am not a lover of the camera. I think photography tends to betray us. My work is committed to exposing and fighting the illusion the camera offers, of presence and absence.

GH: I relate to this. As you know I am very suspicions of the “promise of the archive” when understood as a place that hold records of the past in which secrets are found and revealed. But I believe in the possibility of artistic activization of archives. I want to move to something I find very curious and fascinating about your work: your relationship to the camera and to photography more generally. Many photographers who work performatively and from a specifically feminist perspective (Cindy Sherman, Catherine Opie, Nan Goldman, Zanele Muholi, Laura Aguilar, Lorna Simpson) do so by relying on the camera, something your work seems to consistently resist and refuse. I would suggest that your performative relationship to photography is quite different. It is almost staged against theontology of photography. It is always about breaking the frame, about inserting yourself where you are not expected to be, and about “fighting” the camera and replacing it with embodiment that resists the documentary value of the photographic image. I have never met an artist using so much photography in her work who is so suspicious (hostile?) of the camera. In short [laughing], am I right to suggest that your relationship to photography and to the camera it is not a simple, loving one?

MH: Thank you. No one ever asked me this question. Not like this at least. Well, I am not a lover of the camera. I think photography tends to betray us. My work is committed to exposing and fighting the illusion the camera offers, of presence and absence. I have a serious problem with the impulse to document. From the first time I held a camera, I hated it: it is heavy, expensive, you have to watch it, carry it, take care of it, insure it, and clean it. It is antifeminist from all perspectives for a woman to have to take care of a camera. The darkroom, on the other hand, I used to love! My very early work was all about creating photographic images without the camera. These works are based on light, objects, photography paper, and chemicals. No camera is involved. Barthes talks about the death of the author. I am interested in “the death of the camera” [laughing]. And for the most part I reuse images that already exist. There are so many, why create more?

GH: Despite this antagonistic relationship you have with the camera, you do rely on it to create new communities across time and space. You said that for this reason you use it, despite the fact that you call it “an unethical device.” Can you explain?

MH: If I want to create a community with individuals from an earlier century, or across oceans, or in a confined situation, I have to be able to bring myself (and my friends) to these other times and places. The only way to do this is by creating a community of photographs. I want to be able to go into places and times and portraits and moments which call us. Voices call us. We need to be able to accept the call. This is not going “back” to a place or time we already know (our childhood, the maternal figure); it is heading to an unknown place and time that puts a demand on us.

The camera is the only device I know of that can connect me and other members of such communities. For me the camera is a means of communication, never a means of documentation. If you use it for the latter, most likely you are entering a shady zone where even ethical intentions end up as unethical acts. Rendering others visible, especially if vulnerable, is almost always an act of violence.

GH: A perfect segue. Let’s talk about Lying Woman. Many of your works feature women who are lying down. Can you talk about your interest in lying women?

MH: Our culture is filled with lying women. In the series Lying Women, I accompany women, both known and anonymous, lying down, photographed by unknown photographers. I also look at lying women in paintings, in hospitals and asylums in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. I am fascinated and anxious by the recurring appearance of reclining women in different spaces. And I too lie down. I live in the same apartment in which my grandmother lay sick, and then my mom. Meanwhile I spent years on the psychanalytic sofa.

When I was a little kid, I used to walk in the streets with my mother, hand in hand. As we walked together, usually to her doctor, she would tell me all she knew about our city, Tel Aviv. And what she knew was mostly about women, especially about the women who were lying in bed at that very moment we were walking under their houses. She would whisper into my ear: “Here, on the third floor, a woman has been lying for the past thirty years, never getting out of bed.” Then she would look around making sure the woman from the third floor can’t hear her. My mother mapped out the entire city for me, one lying woman at a time. Tel Aviv appeared to me like a city made of layers upon layers of lying women: poets, sick, crazy, surveilled. Mothers and daughters. Lying down. “This one hasn’t permitted to her daughter to leave her bed for twenty years.” “That one was too crazy to be allowed out of bed.” So, I try to communicate with lying women.

For me the camera is a means of communication, never a means of documentation. If you use it for the latter, most likely you are entering a shady zone where even ethical intentions end up as unethical acts. Rendering others visible, especially if vulnerable, is almost always an act of violence.

GH: I’d love to hear more about your filmmaking, and if you are working on something currently?

MH: My work is always a combination of mediums, including painting, which I rarely exhibit. My films are never strictly films in the traditional sense. They are films, performances, lectures, which include various aspects of image manipulation. My work as an artist is composed, in part, of thinking of infiltration tactics. Entering another period; gaining access to another (traumatic) time and place through photography, archives, videos, sound installations, and performances; developing a new discipline that inhabits a field between art, therapy, and diagnosis; and using materials that were hidden away under designations such as “therapeutic tools,” “diagnostic tools,” or “scientific evidence” is an extremely demanding task.

A short (eight-minute) film I recently made, The Wandering Maniac, 2023, refers to a story of an unknown woman who appeared wandering alone in the fields of Flax Bourton, a village near Bristol, in 1776. She immediately attracted public attention, and was described as “extremely young, and strikingly beautiful. Her manners graceful and elegant, and her countenance interesting as the last degree.” She was reported to have shown “evident marks of insanity” and was cared for by local women until taken under the wings of the Bristol writer and noble lady Hannah More, who paid for her hospitality in an institute known to be the first madhouse in Bristol (I promise you that large number of the occupants were not mad at all). Louisa rose from the archive and called me to take her on a journey of return. Another film, The Hearing is about Elizabeth Packard’s (1816–1897) testimony from her trial, retelling the story of her kidnapping by her husband to the asylum, using the original illustrations that appeared in the papers of the time, creating a channel for Packard’s story to live on.

GH: You are first and foremost an artist, but you’ve also founded the non-profit organization Academy of Her Own. Can you say a few words about this?

MH: For many years I taught at different academies of art. I never noticed any harassment. Then I encountered just some years ago, harassment I call “chronic visual harassment.” The circulating of offensive, racist, and sexist images under the disguise of Enlightenment or as a necessity for, say, telling the history of photography. Students, I understood, experienced this form of harassment so many times. And it is hard to frame because one feels she has to “prove” that the discomfort and violation she is feeling are caused by the images, or the sequence, or, very often, the clash between the images and the tone of the speaker. Among the examples I heard were a cinema professor teaching a class on camera focus, and using a rape scene to demonstrate the importance of “zooming in.” The answer they get from the institution is usually “You’re too sensitive,” or “Being uncomfortable is part of learning.” So, I decided I had to do something and founded An Academy of Her Own, an independent organization for the promotion of women, with the goal of fighting ongoing sexual harassment, particularly in art institutions where “freedom of expression” seems to justify everything. In 2020, artist and teacher Liron Hogeg joined me as Director. Our day-to-day work varies between gathering testimonies of harassment cases, building an archive that can be useful in fighting these cases in the future, and offering a safe space for women to speak and seek legal and therapeutic help. We also gave guidance for art students, draft guidelines and regulations for different institutions. This volunteer activism has taken on a larger role in my life, and we are thinking how to proceed.

GH: Michal, it has been such a pleasure to talk with you. Your oeuvre is immense and your imagination is expansive, I could go on talking with you forever.

MH: Thank you. I would like to end this discussion by thanking you and the editors of the journal for inviting me and giving me this opportunity to discuss and show my work. I love your own work, Gil, and the direction of this journal, which I am thankful for getting to know. Over the years I have been moved, time and again, by women I’ve met on my journey. Women, like yourself, who reached out to me and offered me wonderful opportunities to share my work. I thank you and others for the trust, the support, the curiosity, the friendship and the engagement you offered me. I wouldn’t want to, or be able to do any of my work without it. You are my community.

Michal Heiman is an interdisciplinary artist, (art)ivist, curator, and theoretician based in Tel Aviv. She works across mediums: photography, performance, film, painting, writing, installation, video art, always in relation to her extensive archival research and often in direct (and critical) relationship to diagnosis and psychoanalysis. Her recent projects and exhibitions mainly focus on anonymous and marginalized women who were hospitalized in asylums in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In 2018, she founded the public benefit corporation An Academy of Her Own, which advocates for gender equality in academic art institutions.

Gil Z. Hochberg is the Ransford Professor of Hebrew and Visual Studies, Comparative Literature, and Middle East Studies at Columbia University and the current Chair of the department of Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies (MESAAS). She has published essays on a wide range of issues including, Francophone North African literature, Palestinian literature, the modern Levant, gender and nationalism, cultural memory and immigration, memory and gender, Photography, Hebrew Literature, Israeli and Palestinian Cinema, Dance, Trauma and Narrative. She is the author of In Spite of Partition: Jews, Arabs, and the Limits of Separatist Imagination (Princeton University Press, 2007), Visual Occupations: Vision and Visibility in a Conflict Zone (Duke University Press, 2015), and Becoming Palestine: Toward an Archival Imagination of the Future (Duke University Press, 2021).