Conversations is a series of critical dialogues between artists, designers, historians, critics, and curators on timely issues in the field.

On June 24, 2024, Nicole Emser, art historian of contemporary art from the Caribbean and its diasporas, and Nyugen E. Smith, Caribbean American interdisciplinary artist whose work imagines world-building through the prism of Black cultural identity, informed by history, memory, and ritual, met over Zoom. They discussed the role of storytelling in art practices—art making and art history—as it pertains to the Caribbean and its diasporas. Throughout, they unpack ideas of world-building, knowledge, futurity, language, and joy. Through modes of nonlinear storytelling, bridging disciplines and media, their discussion highlights and models the generative and capacious aspects of diasporic communities and collaborations. This conversation demonstrates the need for, and capacity of, new narratives that privilege alternate knowledge sources and a pedagogical framework that is invested in collaboration.

Nicole Emser: In preparation for our conversation, I was reflecting on ideas of collaboration and what it means to work alongside others. In my writing, I often use phrases like “thinking alongside” or “writing in dialogue with” to express how impactful the knowledge produced particularly by Caribbean, diasporic, and BIPOC scholars is for my own work. And of course, we have been in dialogue for a few years now. Do you recall when the ideas of community and collaboration started to solidify as real concepts for you?

Nyugen E. Smith: I appreciate the way that you’re thinking about other avenues of thought in relation to my practice. I’m always thinking about issues of collaboration and community as well, as an artist and as a researcher. I started to feel the importance of a community as an artist when I first started getting heavily involved in the arts here in Jersey City around 2003–04. I began going to open mic poetry nights. There was a place called the Waterbug Hotel and that was where everybody came on Thursdays.1 Smoke heavy in the air, the smell of beer, the din of exchanged words and ideas, and sense of electricity around the invited poets. This is a performance.

When I was an undergraduate student, I was writing a lot and performing poetry, spoken word, and was part of a rap duo. I also acted in theater productions on campus. So, in the early 2000s I started writing again, and I started to perform at these open mics at the Waterbug. That’s how I really got involved in the community here.

NE: I have never physically stepped foot inside the Waterbug Hotel, but I feel like I have been there—I can see, hear, feel, and smell it. It could be anywhere, or in anytime, or multiple places and times. This highlights, for me, what is so beautiful about storytelling in the Caribbean and its diasporas—how it is a generative practice that transcends and extends time and space. But I want to think in the here and now for a moment, about the kinds of spaces, home(s), and diasporic communities outside of the Caribbean. How do you go about building that diasporic network, and how important is that to you as an artist and person?

NES: I started to recognize the importance of the diasporic community through ARC Magazine.2 I began to reach out to some of the people featured and I feel like a broader network of Caribbean and diasporic artists started to form and get to know one another and each other’s work because of this publication. From 2017–19, I traveled throughout the Caribbean for research on a fellowship and met many of the artists in person after being connected virtually. Because of this expanding community and network, I have made meaningful friendships and have collaborated with others across the region. How do you view collaboration and community as an art historian?

NE: Parts of academia—especially the humanities—are viewed as solo efforts, but that has not been my reality. I value working together in all aspects, particularly the sharing, building, and formation of new ideas and archives. I am the first to admit I do not, and cannot, know everything, and I have learned the most through being part of interdisciplinary communities. I only recently became aware that my experiences were not considered the “norm” for everyone in terms of education. My undergraduate, MA, and now PhD art history programs are all housed within art practice schools. As a result, I always took classes with artists, art therapists, art educators, and curators; and later, these groups made up the students I taught. At Temple, our department works with the MFA students on a catalog, which is a true celebration of collaboration. Art historians and artists pair up, have studio visits, and the art historian writes a short piece about the artist’s practice, incorporating elements that are important to the artist. After revisions from faculty, the writings are paired with photography from the MFA students’ final thesis shows, culminating in a printed and online book. Luckily, I think academic disciplines are becoming blurred as more of us work in an interdisciplinary approach and more people are realizing the benefits of dialogue amongst departments and across methodologies.

Taking action requires collaboration; and collaboration does not exist without listening, learning, and adapting. The type of collaboration we are speaking about is not just a single project; it is forging real bonds—with people and communities.

NES: This paring you mentioned is a great exercise as it models professional practices with real implications for the artist and the art historian. Considering our collective awareness of ways art history has been harmful to different communities of artists, outside of the collaborative assignments for your academic program, do you view your practice as one that is reparative? What are some other transformative ways collaboration can happen in your field?

NE: I hope so. When I started my PhD program, academia was abuzz with the issue of decolonization—almost like it was a single problem to be solved. And then it slowly faded away in many circles, but a lot of us are still invested in working to fix the issues related to decolonizing our fields, which requires action. Taking action requires collaboration; and collaboration does not exist without listening, learning, and adapting. The type of collaboration we are speaking about is not just a single project; it is forging real bonds—with people and communities. From that space change happens. In art history, I hope it will lead toward a larger acceptance of “nontraditional” materials, sources, and timelines as academic knowledge. Making space for and lifting up a diverse range of voices, methods, approaches, and ideas is how I see my own work contributing to this collective goal.

NES: As we talk about collaboration, I am reminded of a collaboration I did in Trinidad with the artist/designer Robert Young, founder of fashion brand The Cloth. My first experiential research trip in Trinidad was to learn about Carnival. During this time, I visited different Mas [masquerade] camps, which were housed within Granderson Lab, a project site of [contemporary art space] Alice Yard. Granderson Lab is home to a residency program for artists, scholars, and curators, and serves as a rhizomatic community. The Mas camp is a centralized location within a community where a group of people who will wear the same costumes as a band come together to make their costumes and spend time together in anticipation of Jouvay and Carnival Monday and Tuesday.

Young’s brand and the Mas he founded, Vulgar Fraction, are based there. I was incredibly impressed with how he managed all of the massive, high-profile creative projects he was doing in that moment. Robert invited me to be a part of a performative photo session to activate the costumes for his band that year. To this day we’re still connected. In January of 2023, during another trip to Trinidad, Robert took my wife Sherene and me on a hike up part of the Northern Range to see the sunrise on her birthday.

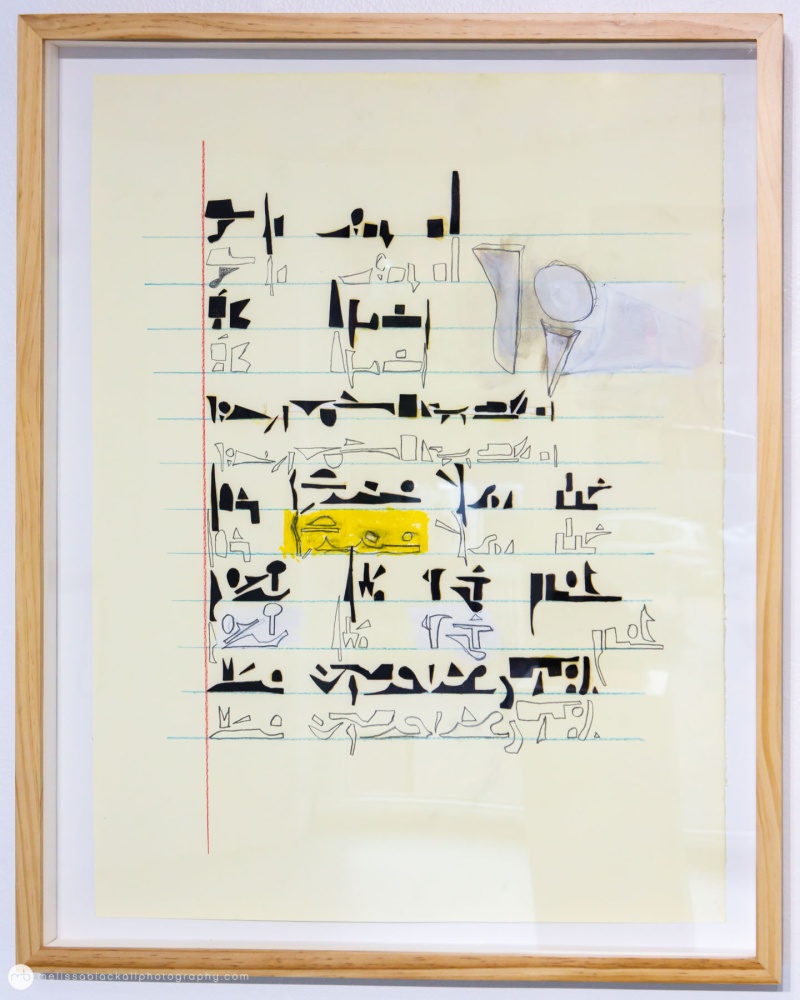

NE: I love that a chance encounter has ended up being so fruitful for both of you. This work also hits on several topics I want to discuss, but let’s start with the inadequacy of language, or the need to reframe the way we conceptualize and speak about art and our world. In terms of the Western gaze, the photos you took with Young are viewed more as a “modeling session” and not the collaborative performance-based piece they clearly are. I know language is an important element of your practice—we have already discussed how poetry and spoken word helped you get back into the art community—but you have an ongoing series entitled Masta My Language, which essentially scaffolds from a poem. It begins with a written meditation about learning a language, Kreyòl ayisyen [Haitian Creole], and learning that one needs to create a new language.

NES: I often say this to my students: Wherever you can, try to structure your life in a way that you can be in that state of mind and that constant train of thought because it’ll help them to make other connections that exist in the universe. It helps you find the poetics and relations through so much else, and it’ll open and expand what you’re doing.3 There are some people who can’t fathom anything outside of what they’ve been shown—this is part of how the human mind works. I remember hearing someone say one cannot imagine a face you haven’t seen before. I’m always contending with human nature and the kind of nuances within my work and related ideas that I want to engage viewers with. I am building a world with the materials and resources that are available to me. As part of this world, I’m creating my own language that can speak to the past, present, and future. My hope is that what I create has a special and purposeful presence. The presence of time is one attribute I hope they have. You (a person) may not necessarily know where to place it in time or geographic location, or sociopolitical context. I’m very interested in those kinds of slippages when talking about future and creating future.

NE: Futurity is an interesting element of your work that I want to elaborate on more. The preponderance of attention on your work thus far has been on themes of ecological and wartime disasters, your use of reclaimed materials, and forced migration. I do not wish to discount these themes, as they are important parts of your work, but I do want to move toward aspects of futurity, play, and joy. Can you discuss your work in terms of futurity?

NES: When I think of the future, I don’t have any idea of what that really looks like—because tomorrow is future. When I create installations, performances, or stand-alone “bundlehouses,” I’m imagining them within a space that is a future—one that contains much of what we have in the present, with references to the past in the way materials and objects are utilized and constructed, while offering ways of managing in the future. Some people might look at these works and say, “Oh, it looks like a postapocalyptic world,” which connotes a breakdown, a collapse in society, where people are resorting to the found object again. This is only one way to see the work.

NE: I have never viewed your Bundlehouse works in the dystopian, Mad Max, wasteland framework.

NES: Oh, I get that all the time. I get these conversations all the time. One of the things at the root of this kind of reading as it relates to futurity are tropes in mass-produced images and films that depict a specific kind of future of collapse.

NE: This also speaks to shifting a frame of reference or how a story is told. The apocalyptic wasteland as a lawless playground can be viewed as just another iteration and symptom of colonial ordering of the land. I prefer to look at your work using an Afrofuturist lens; thinking alongside scholars such as Ishmael Reed and his idea of necromancy—not the pop culture concept of raising the dead—but using “the past to explain the present and to prophesize about the future.”4 There is also something really beautiful that Ytasha Womack theorizes about Afrofuturism, where she writes that it is a framework for everyone to imagine beyond borders and limitations.5 In this future world-making you are doing, I see elements of play and joy coming through. Do you feel that as well?

NES: I think that the element of play in my work is inherent. I don’t always see it as joy. Most of the time, I’m in a pool of serious issues and awful histories. Within the entire ecosphere of a work there are moments during the creative process where the humor exists. Humor sometimes is culturally based, and I think about that too as I am making certain kinds of work. Sometimes you put a little something in there as a kind of little flag or nod. You put out signals so like-minded people that know to recognize the signal and are drawn to it. Sometimes the humor is subtle to those who know. So, play is absolutely there, especially within the performances. What do you mean by joy?

NE: A sense of livingness.

NES: Okay. Say more.

Recently, [joy] is being used a lot in relation to art made by Black Americans. Although I think it’s important that we have the autonomy to frame our work in any way we choose, I see the latching on to this framing by others as a way to brush over important observations and topics rooted in the work.

NE: Kevin Quashie articulates a conception of aliveness based on aesthetics and relation that feels apt to these ideas of storytelling we have been discussing. He points to the capacity of written forms, particularly poetry, as world-building.6 Working with themes of world-building, futurity, and multiplicity strikes me as necessarily containing joy and celebration—at least in some sense—because these elements privilege and demand we pay attention to Black life. I noticed this narrative of joy, livingness, and aliveness tends to specifically come up in texts when you are directly involved. For example, in 2017, you collaborated with mixed-media artist Llanor Alleyne on a site-sensitive intervention at the Barbados Museum and Historical Society. As “The Guard,” you stood watch, silent, barefoot, and often unseen—much like the histories that permeate the building and land. The resulting publication addresses what it means to be in a colonial space, but also documents what would otherwise be lost ephemeral moments of wonder. The text mentions how students on a school trip laugh when nervous, but there is one photo of a teenage girl looking straight at the camera that perhaps provides another reading. She covers her mouth—the photographic record does not give away whether she is hiding a scream or giggle. What is revealed, or made visible to and for the viewer, are her eyes and eyebrows specifically, and her expression suggests a mix of surprise, excitement, and genuine joy. Aliveness is also documented in the form of a short poem, consisting of only five lines and sixteen words. Yet it traverses multiple timelines, spaces, identities:

He is real. / He is alive. / He is present. / He is human. / He has a name.7

To me, that is joy.

NES: I feel you in this framing of joy. I admit, it’s a challenge for me to separate happiness that is connected to a moment in time from the word “joy.” Recently, this word is being used a lot in relation to art made by Black Americans. Although I think it’s important that we have the autonomy to frame our work in any way we choose, I see the latching on to this framing by others as a way to brush over important observations and topics rooted in the work. When I have conversations with other artists from the diaspora, we usually speak about things embedded within the work outside of that doom and gloom space. It’s typically what they felt, the synergy with the work of Caribbean writers and thinkers, and in what ways the work addresses/raises questions about issues that are poignant in relation to the region.

As you know, we talk about narratives and how they are established, especially when someone is making a certain kind of work. Some writers are searching for things within that ecosphere and write through that lens, and often, this approach rarely introduces anything new to the conversation and or produces new scholarship around the work. There are also other narratives constructed by those who are truly invested in the present and future of scholarship with routes of connectivity to the region, and for me they are contributing to the narratives of joy in the way you posit it. What do you want people to take away from this conversation?

NE: That this idea of collaboration—which we have hopefully successfully modeled—does not just work for or apply to the Caribbean or even only to art. It extends beyond that. I really see it as a framework for existing within academia, in teaching, and in artistic spaces. These practices have long existed in the Caribbean, diasporic, and marginalized communities. This collaborative framework feels particularly vital in pedagogy. As part of my committee work with CAA, I ran a workshop about collaborative writing between artists and scholars. People were hesitant at first because it was new to them, but they ended up learning not only something new about a stranger, but also about themselves. I know a few departments that have used the framework successfully, so hopefully we have encouraged a few more to venture out of their comfort zones to research, think, write, and make collaboratively. I also want to ask how you feel this model of collaboration has been useful, but it would only be fair if I answer myself first. Every time we talk, I come away with a new idea or new way of looking at not just your work, but other art as well. The first time we spoke you recommended a book of Kei Miller’s poetry to me, and I have since recommended it to many others. It becomes this rhizomatic network—through collaboration—of shared knowledge. And it does not privilege one set of knowledge over others; that is what feels really exciting to me—the multiplicity of ideas and knowledges at the same time.

NES: Early into a recent project I thought about the “Iconoclasm as Methodology” section of your dissertation on my work and this contributed to the way I entered the conceptual aspect of the work. When I look up the definition of scholar, Merriam-Webster says:

1: a person who attends a school or studies under a teacher: PUPIL

2: a person who has done advanced study in a special field

I started by looking this up because I equate a serious art practice with scholarship. I would argue that as an artist enters mid-career—we can use mid-career for those who have formally studied art, and should consider other metrics for the self-taught, and for those maintain serious practices independent of the art world—they have at least studied their medium extensively and have advanced knowledge of materials and processes. We can then add their area(s) of focus and study of specific subject matter related to their practice to the conversation. So in the case of an academic and mid-career artist being in dialogue, I recognize this as an exchange between scholars. Could such a deliberate framing fundamentally affect the way collaboration is imagined?

Nicole Emser is a PhD candidate in art history at Temple University. Her dissertation traces the systematic practices of ordering Caribbean land from the colonial to the present and maps the visual and material strategies used by contemporary artists to locate and make other worlds to create futurity. Her work has been supported by the Stanford University Libraries, the Huntington, the Lewis Walpole Library, and the Clements Library.

Nyugen E. Smith is a Caribbean American interdisciplinary artist primarily working in mixed-media drawing, assemblage, and performance. He is interested in world-building through the prism of Black cultural identity, informed by ritual, memory, history, and art-making processes that prioritizes the use of previously used materials. Smith holds an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

- The following information is stitched together to form an archive built on community and care. For theorization on co-constructed archives and rewoven community memories, see Li Machado, “The Portrait as Archive and Activism in Queer Chicanx Los Angeles,” Fellows Lectures in American Art, Smithsonian Museum of American Art, May 9, 2024. The Waterbug Hotel no longer exists physically. At one point, Lex Leonard ran the space at 143 Christopher Columbus Dr. in Jersey City, New Jersey. He was no longer involved with the building when it caught fire on April 7, 2022, yet recounted the afterlives present in the building: “it was a stop on the Underground Railroad . . . I, along with a myriad others, called it home, an inspiration, an escape, an institute.” Susan Justinano describes seeking out the “legendary” Waterbug Hotel, “which was a community center of sorts for the city’s art performance arts community where poets, musicians, and other artists congregated.” ↩

- ARC Magazine was founded by Holly Bynoe and Nadia Huggins in 2011 as a biannual print and online visual arts magazine with the aim “to build awareness by fostering exchanges and opportunities that expand creative culture, within the visual arts industry across the wider Caribbean and its diasporas.” ↩

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 181–88, esp. 181. ↩

- Bruce Dick and Amritjit Singh, eds., Conversations with Ishmael Reed (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1995), 51–52. ↩

- “Afrofuturism provides a prism for examining this issue through art and discourse, but it’s a prism that is not exclusive to the diaspora alone. Whether by adopting the aesthetic or the principles, all people can find inspiration or practical use for Afrofuturism to both transform their world and break free of their own set of limitations.” Ytasha Womack, Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2013), 192. ↩

- Kevin Quashie, Black Aliveness, or a Poetics of Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 2. ↩

- Llanor Alleyne and Nyugen E. Smith, The Guard: An Intervention at the Barbados Museum and Historical Society (Baltimore: Mare Projects, 2021), 36. ↩