This review first appeared in Art Journal vol. 83, no. 2 (Summer 2024)

Misty Gamble: Of Flesh and the Feminine, at the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts, Lubbock, Texas, September 1–October 28, 2023.

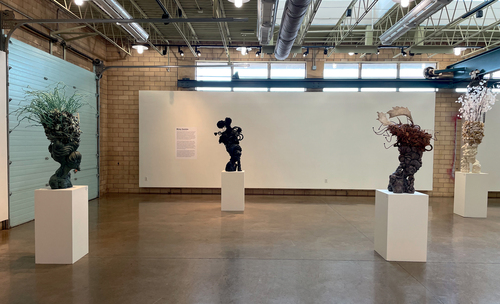

One of the first features to capture the visitor to Misty Gamble’s exhibition Of Flesh and the Feminine is the peculiar poetics of visual and cognitive incongruity. The show revives while transforming into a phenomenological voyage the surrealist idiom of the uncanny at various stages of the aesthetic experience. The eerie awareness of something defamiliarized and estranged begins at the first encounter, when viewers enter the gallery to face the blank statement of white walls and a vibrant interior populated by the ceramic busts of eight majestic female figures.1

The carefully spaced-out orchestration of the series gives emphasis and weight to each esteemed ceramic lady. The lavish assembly exploits unity and variety by featuring a consistent template, technique (modeling and casting), and material (clay and ready-made), while granting a unique personality, customized traits, and idiosyncratic paraphernalia to each spectacular presence. From entering the peculiar mise en scene of the aristocratic beau monde, a sense of rhythm bedazzles and lures the eye on its meandering path across the room with trappings, enticements, and details.

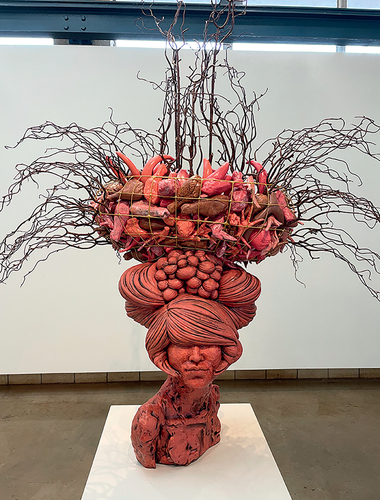

Evoking the vitrine of an antique fashion store, the reverberation of pattern and variation is enthralling and persistent. Each sculpture is made of the same material—the tactile and pliable yet weighty and earthly matter of clay; each head is surmounted with a basketlike headdress on top of an elaborate set of curls, and every effigy stands propped on a pedestal so that its earthenware mass of locks dwarfs everything else on our eyeline. Tresses, flourishes, and decor vie for attention as a sight to behold, while the monumental headgear surpasses all visual competition. Reveling in adornments, each coiffure owns and dominates the stage, playfully inserting accoutrements (branches, flowers, and tassels) into the space of the viewer.

The visitor who ventures to meet each mademoiselle tête-à-tête will delight in joining a polite society. Endorsed by the artist’s statement, the most immediate allusion is to the Rococo salon, where spectacle ruled, and women commanded respect by conquering the senses with ceremony, costumes, and sophistication. However, once inside the “salon,” the mind is forced to abandon the comfort of dispassionate observation because the Rococo signature appears strangely entwined with some bizarre, out-of-place props and predicaments. The actual (or, more precisely, surreal) encounter with the defamiliarized and estranged begins as one approaches each ceramic figure. The eye is taunted by a rich cornucopia worthy of a cabinet of curiosities, so a close interaction is needed to examine the delicate features.

The first incentive to get to know each female persona closely is prompted by the busts’ peculiar orchestration. The spatial arrangement makes it impossible to capture all the women from a single vantage point at once as each averts her visage to a different side of the room and faces (or possibly gazes) in a different direction. In addition, the title of each sculpture appears on the back of its pedestal, pointing away from the gallery entrance. Therefore, any proper etiquette of high society—any approach that would involve learning the name and catching a glance of the noblewoman’s visage—induces the viewer to walk around her pedestal, as if circumambulating a shrine, and engage with the intricacies of her decorations.

Marked by a distinct earthly color and individual accompaniments, each sculpture draws the eye into her orbit. Challenging one’s sequential path of discovery, each has a unique name and temperament and proudly asserts her place in a community that collectively holds the clue to a shared enigma. Inviting us to take a retrospective journey in time, the embellished bust of a magisterial female evokes various prototypes and historical eras, from famous Egyptian queens (recalling the bust of Nefertiti) or Greek goddesses (such as armor-clad Athena) to mythological creatures (most sumptuously, Bernini’s take on Medusa) and Roman matronas (think of the Flavian women). However, it was the unrivaled Rococo period—a time of erotic sentiment, theatrical femininity, performative gender, and rebellious design of wealthy female patrons—that turned personal adornment into a work of art and transformed attire—particularly, hat and coiffure—into an instrument of conquest and desire.

Poise and pomp ooze from every single frill featured in the trap of rococo enticement—from the coded messages of pastel colors, vegetation themes, and exposed décolletage to the tacit insinuations of ribbons, garlands, and feathery beautifications. The period style can also be detected in the immense headgear perched on the towering tresses, while similar quotations inspire the faux flora, synthetic braids, and golden tassels crowning the giant headdresses. The most theatrical of all, however, is the baroque tenor of opulent, colossal hair. Twisting and unfurling its tactile body with aplomb, it becomes a principal performer in the exhibit. Heaped like a pylon atop the head, fashioning sinuous curls that cover the face or swirl to the side, and trailing like billowing scrolls behind one of the busts, the hyperbole of styled yet unbridled coiffure is so palpably assertive that it acquires its role and personality.

The masterful handling of technique and material—which alternates polished and coarse surfaces while contrasting crevices with the smooth skin of glazed ceramics—is at its best when bringing to life the movement, texture, and weight of such intemperate but epic hair. Yet as soon as the mind settles on the allegory of Rococo pageantry, the viewer is prompted to acknowledge another, less obvious but equally industrious, conceptual (corpo)reality. Untamed curls begin to unravel under the gravity of earthly mass, granular torsos seem to fall apart under the “metal woven cages” nested in the coifs, while titanic tresses open their fissures to reveal an ecstatic carnival of flesh served as a “gigantic meat bouquet” on the “pedestal” of each ceramic figure.2 Discovering an uncanny feast of extremities—chicken drumsticks, thighs, wings, or feet next to antlers and horns—atop the women’s heads, the viewer is forced to confront the estranged and seek another frame of reference.

Beneath the rococo veneer, an exegetic dive into the materiality of the exhibit would unearth primordial and primeval agencies. Translating form and space into figurative narrations, the energy of the raw material twists, unwinds, and sprawls—untamed and unrestrained by social bounds—to engender an intra- and interaction of body and matter. Their elemental symbolics engage all senses and multiple sculptural faculties (movement, texture, mass, void, color). Thus, the physical placement of energy—the bodying of limitless matter through figuration—and the infinite transmutation of the carnal become inter- and intraconnected. Through regenerative cycles, art mimics the percipience of nature in which matter and energy unite as life foreshadows the end of flesh, and death forebodes a new beginning. In the ancient lexicon of such creation myths, the carnal signifies life and death or vital energy and mortal flesh, while matter embodies nature, sustenance, beginning/end, and the perpetuance of mutability.

It is not accidental that the exhibition’s title links essentialist notions of womanhood (“the feminine”) with ideas of excess, consumption, materiality, and the corporeality of life and death or food and nourishment (“flesh”). In grand cultural narratives, women’s bodies are framed as vessels of matter—desired, desirable, or necessary for procreation; that is, destined to generate flesh—while death is mythologized and feminized in symbolic terms as a journey into the depths of the earth and its primordial womb, the grave. The show evokes such connotations through figural tropes (metaphors and metonymies)—from flesh, meat, and fruit nested in cages of food to slowly decomposing as if returning to ashes, naked and grainy clay torsos. It is a feast of the agency and riches of matter: matter as incarnate be-ing or discarnate state of becoming; matter as transient form and intransient essence; or matter as substance and sustenance, vessel and void, force and dwelling—matter that generates life, while harboring death, and everything that is.

The materiality of body and soil is brought to spectacular life by the earthliest of all materials—the raw clay of the sculptures. Even after being fired, glazed, colored, and shaped into molds, it carries the vitality of earth that inhabits all forms and satiates the space with its heavy, extant, palpable presence. Placing and bodying all solids and voids, the matter of clay—as abode and source—rests entangled, pliable, and active. An archetype of life’s mortality, it bulges, twists, and weaves through the interstices of time to engender metaphors of flesh and feasts of death—wings, thighs, bones, horns, and other metonymies. Matter and clay both conceal and shape the most estranged component of the exhibition—the uncanny collection of treats and menagerie of meats rendered like a carnivore’s dream in each woman’s headdress basket.

The glazed ceramics shine at their finest when depicting the fruit of the earth and the banquets of flesh served on a platter by each “fantastical coiffure.”3 The defamiliarized buffet is both salacious and repellant as it mixes tasty renderings of fruit and meaty delicacies or delights—such as poultry wings and thighs—with inedible byproducts—readymade antlers, faux flowers, and synthetic hair next to casts of chicken feet, bones, horns, and claws. On heads leaning to the side or bent forward under the weight, the baskets of goodies are fastened with thin metal wires. Filled to the brim, they resemble overcrowded fishing nets and echo the “metal woven ‘cages’” of upturned “French revolutionary era pocket skirts” worn by the women of fashion.4

Poised to crush each female torso and neck, the assortment of edibles and inedibles looms powerful and sublime, threatening to collapse and destroy the balance of this peculiar arrangement. The ominous spectacle arouses and arrests the gaze by affronting one’s sense of taste while provoking and toying with conflicting affects and emotions. At this point in the journey, the valley of the uncanny bedazzles at its best, the metonymy unfolding with collective thrust and potency. Drawing the viewer into a mysterious ritual, the feast for the senses paralyzes and consumes the gaze to provoke the unnerving sensation that the order of things, or the law of the universe, is imperiled by an unstoppable force of nature.

The title of each bust and the artist’s statement offer food for thought in this aperture between perplexity and anticipation. Each woman’s name refers to a breed of chickens—some exotic and foreign, others familiar and domestic—and the properties of each variety are playfully encoded in the features, personality, and color of its ceramic matrona. For instance, Partridge Plymouth Rock is “a friendly and calm” American breed of “good sized birds” weighing between four and eight pounds.5 Known for their “beautiful red and black partridge feather pattern” and reddish-brown females, they boast “one of the best productive laying hens.”6 Accordingly, the Partridge Plymouth Rock figure is similarly reddish-brown with black folds and highlights. Displaying a “friendly and calm” disposition, she carries a large clutch of eggs in her magnanimous French twist and offers a “good size” bounty of reddish-and-brown animal parts nested between the branches of her basketlike headdress.

Likewise, the “Bearded Buff Laced Polish”—one of a variety of chickens with beards—refers to an ornamental breed of birds characterized by golden buff feathers laced in creamy white. Calm and friendly, they are famous for their “top hats”—a crest of “crazy feathers” growing from a knob on the skull—which can “limit their vision” and make them “timid and easily startled.”7 Translated into sculpture, those attributes inspire the creamy hue and gold patina of the white madame and infuse her serene, pensive posture, with a head bent forward under the weight of an explosion of curls and a soaring turban. Blinding her eyes and gushing down like a spiraling stream along the face, her hyperbolic “feather crest” mimics the top hat-beard of the ornamental chicken.

In contrast, the graphite hue of the black ceramic dame echoes the fibromelanosis of Ayam Cemani—a rare Indonesian breed termed the “world’s most bewitching chicken”—which possesses a dominant gene causing its black hyperpigmentation.8

Lastly, the docile temperament and cultural origin of Buff Brahma, a gentle heritage breed of chicken named after India’s Brahmaputra River, evoke the placid demeanor of the yellow femme and her most distinct trait, unique in the series. Her lush ponytail of thick hair scrolls twists like a river behind the nape and flows into a net full of animal limbs and paraphernalia.9

Encoded in sculpture, the parable is masterful, persistent, and revealing. It exposes the marketing strategies employed by aficionados of exotic bird breeds and commercial sellers of common-variety chickens, who anthropomorphize and sensualize their commodity or use glam vocab to promote their live product. The viewer is provoked to reflect on how patriarchal paradigms essentialize and objectify women as sex toys or food for the eyes—flesh and meat to enjoy—and as a one-dimensional labor force destined to bear and raise children. Embedded in the show’s title and the artist’s comparison of “human animals and non-human animals,” the allegory of women as flesh and femininity as food, however, leaves us still perplexed because it does not explain the feasts of meats crammed into the “cages”—wombs of the ladies.

Misty Gamble’s statement provides further clues by inviting her audience to reflect on the predicament of our time and its “social, political, or environmental” connotations. The artist discusses the devastating impact on the environment of the excessive meat production and consumption, emphasizing the exploitation of resources, particularly land and animals, and painting a daunting image of earth as “a dehydrated, decimated land.” The sense that the cosmic balance is being disrupted looms large and sublime as people (addressed as a collective “we”) have become disconnected from our roots by forgetting that “we are animals, we are nature, and the earth is not just the environment but our home.”

Taking on an active (and activist) role, Gamble urges her fellow artists to embrace the task that is most pressing—to help bring about social change by engaging in a “discourse about the earth and all its inhabitants” and aid in the survival of future generations. Thus, her work aims to inspire a dialogue that extends beyond the walls of the gallery. Drawing upon the intersection of feminist ideas and environmentalism, the exhibit makes tangible the image of an exploited earth, the entangled interdependence of species, and the notions of ecofeminism. As the statement reveals, the show is inspired by the 1990 controversial but “classical book,” The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory, by feminist vegan activist Carol J. Adams. Grounded in feminism and vegan critical theory, the book draws parallels between meat eating and patriarchy and connects vegetarianism with feminism.

Adams’s ideas provide context for using metonymical fragments (by-products and meats) as signifiers of the “absent referent”—the visual trace of a body that is now fractured and lost but bears a memory of what was once active and breathing. The capitalist culture of excess and exploitation, and a patriarchal order gone amok in an endless desire to proliferate, consume, and discard, finds a powerful artistic voice in the uncanny metaphor of eight silent, frozen women. While unfamiliar objects and bodies are easy to dismember, consume, and forget because they remain anonymous and invisible, the collective fragments of “non-human animals”—the metonymies of absent referents—are prodigiously active and present in the tectonics of the exhibit. Mounted as grave repositories of flesh, waste, and death, they threaten to collapse and crush the armless, broken torsos. Abrasive, gritty, and embattled, these ageless and disintegrating figures stand as metaphors for an imperiled earth and the lost balance of an ancient cosmic order.

In the annals of history, the famed excess and overindulgence of the Rococo epoch—the series’ principal reference—resulted in a violent societal collapse that caused the demise of the aristocratic regime and the bloody reforms of the French Revolution. The show’s voyage, however, does not provide any answers about the mystery of its protagonists’ faith or humanity’s current predicament. After taking the viewer on a self-discovery journey through history, myth, nature, and time, the visual anecdote closes with an open dilemma: Will the Anthropocene listen to the silence of matter and the absent referents of a “decimated” earth, or will it reprise the transient spectacle of the Rococo era?

Maia Toteva is an assistant professor of global art and visual culture at Texas Tech University. Her monograph on the linguistic branch of the global conceptual art movement is forthcoming.

- The show consists of “a series of eight ageless ceramic life-size femmes, depicted through torsos, and inspired by the Rococo.” Misty Gamble, exhibition statement. The blank stare of the gallery walls is interrupted only by the artist’s exhibition statement which faces the viewer—enlarged and displayed on the wall opposite to the entrance—as an important voice and actor in the exhibition. ↩

- “These armless busts hold up heads with enormous baroque fantastical coiffures and operate as pedestals for the gigantic meat bouquet of animal fragments and accoutrement. Atop the head sits metal woven “cages” or upside down French revolutionary era pocket skirts holding cornucopias.” Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. In the spirit of the carnival, the gigantic woven cages and inverted “skirts” full of food are turned upside down and placed on top of the women’s heads as if to signal a reversed, dysbalanced cosmic order. On the carnivalesque, see Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. Helene Iswolsky (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984). The book was written in Russian in the 1930s and published only in 1965. It was first translated by Iswolsky as Rabelais and His World in 1968 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press). ↩

- “Partridge Plymouth Rocks,” Stockman Feeds & Western Wear, accessed January 12, 2024; “Partridge Plymouth Rock,” Agrarian Indy, accessed January 12, 2024. ↩

- Misty Gamble, exhibition statement. ↩

- “Buff Laced Polish Day Old Chicks,” Meyer Hatchery, accessed January 12, 2024; “Buff Laced Polish,” McMurray Hatchery, accessed January 12, 2024. ↩

- Patrick Winn, “Behold—the World’s Most Bewitching Chicken,” USA Today, October 10, 2016. ↩

- “Misty Gamble—Of Flesh and the Feminine,” Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts. ↩