The Feminist Interview Project, organized by CAA’s Committee for Women in the Arts, examines the practices of feminism by interviewing a range of scholars and artists. The project aims to preserve the living histories of feminist art practices, while interrogating and expanding the boundaries of what might be considered feminist. Throughout its interviews, this project reimagines the possibilities of feminist practice and feminist futures by exploring a diversity of perspectives and approaches to research. This collection of interviews aspires to critically examine the relationships between feminism, feminist art, and the lived realities of women, nonbinary and female-identified artists and scholars across the globe. For our ongoing collaboration with Art Journal Open, the Feminist Interview Project is excited to present artist Kay WalkingStick in conversation with art historian and curator Elizabeth S. Hawley. The two met for a conversation over Zoom on July 23, 2024.

Kay WalkingStick (photograph by Rich Schultz; provided by the author)

Elizabeth Hawley (photograph provided by the author)

Elizabeth S. Hawley: Kay WalkingStick’s practice, which spans six decades, will give us a lot to talk about today. It’s a practice that addresses critical issues pertaining to Indigeneity, sovereignty, colonization, decolonization, gender, sexuality, feminism, among other things. So, much to do here, and I am honored to be speaking with you, Kay. I’ll just ask you to introduce yourself and your practice in in your own words before we launch into questions.

Kay WalkingStick: Hello, I’m Kay WalkingStick. I’m a painter. A Cherokee. A biracial woman. I suppose if this is about feminism, I’ve certainly been a feminist all my life. My paintings have to do with a lot of various topics, but I suppose primarily it’s who I am, in my position, how I view the world. It’s my worldview. I think that as a painter, well, there are not many of us left. People are not becoming painters, I don’t think. It’s something that takes years to learn to do well, but when it’s done well, it speaks to people in the most profound ways. I know it for that.

ESH: Wonderful, thank you. I think we’ll proceed with our most foundational but perhaps also most difficult Feminist Interview Project question: What is feminism for you?

KWS: Feminism is being. This is who I am, and I can’t imagine anyone, any female, not being a feminist. But in a way, I look forward to a day when we don’t have to promulgate that notion of feminism, that we are all one on this planet, and there should not be any divisions between gender. There’s too much concern—in a way, concern is not the right word—but I feel that that people should be comfortable with who they are and feel permitted—by whatever constraints there are in the world—to be whoever they choose to be and operate in the world, not as primarily that person, but just a person. Now, of course, that’s a dream work. We don’t have that yet.

ESH: In many ways, you came to maturity as an artist in the 1970s. You were painting in the ’60s, but then attended graduate school in the early ’70s and received your MFA in 1975. This was a time of such heightened social activism, and your work from this period is certainly influenced by second wave feminism and the American Indian Movement (AIM). And there are many works we could discuss here, but I’m thinking in particular about the apron works that you did at this time, pieces like Gray Apron and A Sensual Suggestion, they seem to reference an identity that is marked by these expectations of womanhood as well as Indigeneity, right? This sort of swath of fabric has also been compared to tipi forms, and I think led to some of your later works in that realm. So, could you tell us a little bit about embarking on your career at this at this moment, and how feminist and Indigenous concerns came out in these early works?

KWS: I think I have to preface it by saying that I married in 1959 and had my first child in 1960, so the ’60s for me, while I was making art at home and painting, also involved child rearing and making a home for my husband and children.1 So, I was mom—I was mom who painted, but I was mom. Not that I stopped ever being a mom. I still am, and a grandmom as well, but those years were important to me in my own growth, surprisingly, as an artist because as I said, I was making art, and I was thinking about what I wanted to do and how I wanted to live my life and how I wanted to proceed.

And at the end of the ’60s, I decided that I really needed graduate school. I needed to get better fast, and I didn’t think I was going to get better as an artist quickly if I stayed primarily working at home. So, I applied for and won a Danforth Fellowship for Women to return to graduate school.2 And God bless them, they paid for everything and, I believe, included my transportation back and forth. It was a very generous fellowship, and it came at a time when it was very needed, because there were a lot of us [women] who realized that we really needed to go back to school. And it would have been impossible for me to do that otherwise.

Truth is that everything that we do and everything that we are and everything we see and everything that we remember goes into those paintings in one way or another, everything we are goes into those paintings.

I chose Pratt. I certainly looked at a lot of other schools. I was rejected by one school, specifically because I was older, which really pissed me off. But I was thirty-eight when I went to graduate school, and it was a wonderfully exciting time. And as you said, a lot of social changes; second wave feminism was really big in ’70, ’71, ’72. I marched with everybody else, and it was an exciting time. I felt very strongly that it was women’s turn to be accepted fully into the culture in every way. And I had always felt that.

Personally, I was raised by two women. I was raised by my mother and my Aunt Lil, who was a church secretary, and my father was out of the picture by then. I was the last of five children, and my mother left my father, pregnant with me. It was a difficult time, by the way. I was born toward the end of the Depression. It was a hard time for everyone. I don’t mean to digress, but it may be important that people recognize that I was born before the Second World War; the war was my childhood. So, I have all that. And the truth is that everything that we do and everything that we are and everything we see and everything that we remember goes into those paintings in one way or another, everything we are goes into those paintings. I seem to have wandered away from the question.

ESH: No, I think that actually gets back to even these apron works that I was thinking about when I was formulating this question. You mentioned the 1960s and, of course, into the ’70s, child rearing and domestic responsibilities. And I look at the sort of handprints, the fingerprints that appear on so many of those aprons, which, on the one hand, there’s such a modernist painterly sensibility to that. And you might think of a painter’s smock, which I think is, if I remember correctly, what originally inspired some of these works.

KWS: A painting apron is what they are. It’s a picture of my painting apron. Which I had made, by the way, out of linen canvas.

ESH: Oh, so the painting apron was actually of canvas as well, fantastic. But those fingerprints also evoke, for me, the responsibilities of rearing children; they evoke so many things. I think that kind of tactility, there’s a bodily component there, sort of the body present and absent. You’re not overtly picturing the body, and yet there it is in those paintings, via the apron form, and those fingerprints.

KWS: I was trying to address this idea that I am a painter, and yet I’m also a mother and I have these responsibilities, and I think that the apron represented those responsibilities to me. And yet the apron is hung very tenuously. It’s on a very tenuous triangle. And I was looking to a lot of the things that were going on at that time in New York, and the aprons were certainly iconic forms for me. They were certainly very meaningful to me, and on many levels. I felt very strongly about the notion that women can do anything. If they put their mind to it, they can do absolutely anything at all. God bless Kamala Harris. Boy, I’m so pleased about that. I’m so pleased. Oh, God. Anyway. . . she’s gonna’ get that bugger.

ESH: I think many of us are pleased with this recent—recent as of this interview—news.

KWS: At any rate, she’s going to be a great president. And I think that women can do anything. And I feel very strongly about that, and I always felt very strongly about that. I think that those paintings are about that. They are: here I am. Here I am in all of my personhoods, of all the people that I am, this mother, this cook, this painter. I am powerful. And there’s a power that comes through those aprons that was really important to me, asserting that.

ESH: A later work that has struck me as so powerful is You’re an Indian?, from 1995, so some twenty years later, but it still sees you continuing to grapple with these issues of identity, as so many artists were in the ’80s and ’90s. And I’m wondering if you can tell us a little bit about this piece and what had changed—and what hadn’t—in that intervening twenty or so years in your life, in your practice?

KWS: Well, a lot changed, certainly socially. The Indian movement of the early ’70s was very meaningful to me.3 I was so glad to see that Native people were standing up and saying, Hey, we have rights. We’re here. And that notion that we’re still here is an important one to tell the world, and that we have rights like every other American. You know that Native people in this country weren’t made citizens until 1924, and my father was born in 1894, so he was thirty years old when he became a citizen, which strikes me as wacko. But all right, that’s the way it was. But we are citizens like everyone else, with the rights of everyone else, or at least, should have the rights of everyone else. So, I felt strongly about the Indian movement. AIM sort of broke up, but the notions that they presented certainly didn’t go away. Everybody should read Paul Chaat Smith on what it means to be an Indian. He’s brilliant. And in addition, the feminist movement continued. It changed a little bit, but it certainly continued. There wasn’t so much marching . . . The ERA is still floating out there. The Equal Rights Amendment is still . . . I mean, that’s a whole other lecture, of course, but it’s still floating.

ESH: I think it’s on the job for our next president, isn’t it?

KWS: One of the things.

ESH: One of many things [laughter].

KWS: One of many things she’ll be taking care of! [laughter]. Anyway, that picture—You’re an Indian? [said in an incredulous tone] is what it is, like what, you’re an Indian? I was raised in a white culture. My mother was Scotch-Irish, and my father was not a full blood. My grandfather was a full blood. So, I guess I look like a white lady. I mean, I look at myself in the mirror, and I look like an old Indian, but apparently, I looked like a white lady [laughter]. And I had on my cowboy hat, and I went in to see a gallery director named Ivan Karp in Soho, who has now passed, but he was very famous, and he was very good-hearted. And he was funny, and he liked a good joke. And so, when I came in and introduced myself and showed him my work, he said, “You’re an Indian? I thought you were a Jewish girl who changed her name.” And I’ve always thought that was very, very funny. And I made a print about it. And a lot of other people think it’s funny too [laughter]. It very often appeals to Jewish people because they get it. But there were also people who thought I shouldn’t show it because they thought it was offensive. I’m not sure who it was offensive to. Maybe the people who were neither Indian nor Jewish were offended. But it’s always been a lot of fun, and it’s in the Museum of Modern Art, so it apparently has gotten past its offensiveness.4 I must have made it twenty, thirty years ago.

ESH: There’s such humor here, but it does speak to very serious issues about expectations, what it means to present as Indigenous or as what someone thinks an Indigenous person should present as.

KWS: People are usually disappointed in my face. They expect me to be a little bit browner. I come from a variegated family—a lot of African Americans have the same thing in their family—that, you know, my one sister was much lighter than another sister, like that.

ESH: This idea that you’re somehow not Native enough; I think of Erica Lord’s I Tan To Look More Native. Or some of James Luna’s works that deal with dual and competing identities and expectations about identity. But this, You’re an Indian—question mark—is so powerful. And I think part of what makes it powerful is the humor.

KWS: Oh yeah, it’s funny. Yeah. I mean Ivan Karp was trying to be funny.

ESH: On the issue of expectations, this piece and a lot of your works also speak to the way the art world can be very eager to narrowly position someone as a Native artist or a woman artist. Can you talk about how you’ve navigated those categories, which can be reductive?

KWS: Truth is, I am who I am. People have to take me the way I am. I realized that when I was a kid. My mother was very strong and very influential in my life and she always said, “Stand up straight. You’re an Indian. You’re a Cherokee. Be proud.” And she meant every word. She was very strong about that. The other thing she gave me every day was, “A smart little girl like you ought to make something of herself.” And you know, that’s a wonderful thing to give to a little kid and she never stopped [saying] it. She reminded me all the time that I was smart and I should do something. And, truth is, I’ve just been doing what my mama told me to do my whole life.

ESH: That’s so beautiful.

KWS: Sweet, yes.

ESH: There’s so much to be said here about the importance of these maternal ties, these through lines—matrilineal ties, perhaps we could say.

KWS: Yeah. I mean, she thought that I was a wonderful artist. And that’s really a big thing, to have people that are close to you believe in you, believe that you have something to give the world. She believed that I had something to give the whole world. Amazing.

ESH: That support is so key. And I do sometimes wonder about the artists that might have been, if they had had that kind of support, familial and otherwise.

Another throughline that I very much see in your work, is diptychs. You began working in this diptych format in the 1980s and that has continued to appear in your work since, as has landscape. And I think there are any number of recent works that we could reference here in which you have this vast landscape, in some cases a waterscape, that’s presented in these two panels with Indigenous symbols that are overlaid on the vista. And I’m hoping you can speak a bit on how you came to this subject, and what about it has really sustained you over these years.

KWS: You know, I think that painting has always been a challenge to me. I’ve never thought it was easy to paint. I can draw easily, but painting is not an easy thing to do. And the challenge is making art that is strong and is crafted—I believe in craft—and also speaks to people, because painting is a visual language, and I think it speaks of things that cannot be said otherwise.

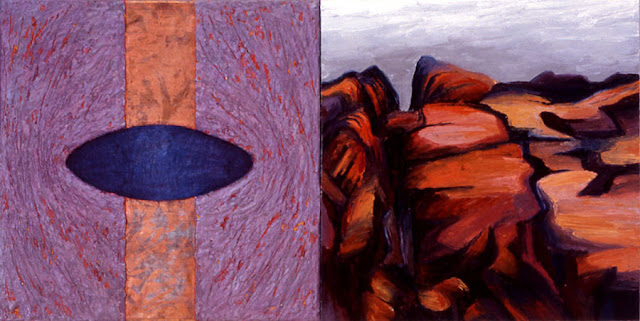

The diptychs evolved, like everything else does, slowly, but I started doing diptychs in which one side was a naturalistic type of landscape of some sort, and the other side was an abstraction. And it had to do with the natural world and the interior world. The point is that each side had something to say to the viewer and to the other side. I mean, they were like stanzas of a poem. They were related, you know?

I was doing a lot of reading about Nez Perce and the Nez Perce women. And of the things that that struck me was the parfleche bags; the Nez Perce parfleche bags are magnificent.5 Parfleche bags are always made by women. Gaylord Torrence, who wrote a long book about the parfleche bags of the north, said that they were made by the women because women are closer to the cosmos.6 So, of course, it’d be the women who did it. So, women made these wonderful parfleche bags. And my thought is always that America’s earliest modernism is in those parfleche bags, these modernist paintings. They’re magnificent.

I did a painting that combined the parfleche bags with the mountains of Oregon [Wallowa Mountains Memory, Variation]. So, I combined these two things, and it was those two or three paintings that actually influenced the use of pattern with the landscape. They were not abstractions like the earlier diptychs. They were actually patterns.

And then the patterns are the patterns of the people who live, and have lived, have always lived, in that area and still do, unless the tribe was decimated by disease or warfare. Those areas, the people who traditionally live there are still there very often. I mean, if they can be, they’re there. They sometimes have to work elsewhere, but over and over again, you meet people in an area and this is their homeland. Even though they’re not living on a reservation, they are still living in the area that was their traditional homeland.

So anyway, that’s how the patterns came to be on the landscapes. I travel, take photographs, make drawings, and come home and make paintings of the landscapes. The paintings are usually pretty big, and I usually reference pretty closely what I’ve photographed or drawn. I sometimes will put in a tree that I saw in that area because I need a tree someplace. [Laughter] I mean, you know, just for compositional reasons. I will move things around, but it’s still from the same area. I never make it up. I don’t make up things.

ESH: You mentioned the parfleche bags being part of what led you to this project. It was part of the early evolution of this project, and that working with hide, those bags being women’s work, that is, those are women’s customs.

KWS: Women who were particularly good at it.

ESH: Talented women’s work.

KWS: There were women who were better at it than other women. Not everyone has terrific hand skills. And they were particularly honored, those women. It was an important thing to do, and they were oftentimes very large. I don’t know if everybody has seen parfleche bags, but what’s surprising about them, when you see the real thing, they’re big.

ESH: This idea of women’s work, particularly Indigenous women’s work, segues into my next question, which is that I look at these landscapes, and I think in many Native communities, women are considered to have this innate connection to the land, right? They draw power from it, they’re responsible for protecting it, they are these cultural leaders and knowledge keepers because of it. It’s rooted in the land. And I’m wondering if that’s something you think about in in producing these landscapes as well.

KWS: No, I don’t. I was raised in a white culture. The women that I lived with were capable of doing anything, I thought, but we didn’t live on a farm, so we didn’t farm. The women are traditionally the farmers in Cherokee tradition. They also had a great deal of importance in the tribe; grandmothers, especially, we old ladies, had a lot to say. It is said that they chose the time to go to war. It was the grandmothers. I can’t imagine doing that, but I’m sure that they were capable. These old women, they knew what was going down. Women have always had an important place in Native culture and their place was recognized as important. As I said, these women who painted their parfleche bags were very honored. It was an important role.

But I think that in many white cultures—and many cultures around the world, and Indigenous people around the world—what women do is honored. After all, in early societies around the world women were considered magical. We produce children. If that isn’t magic, I don’t know what is. Women do have an aura of magic about them, and I don’t think that’s just Native women. I think that’s women everywhere. So, I can’t say that I was particularly influenced by a Native culture. I was much more influenced by a religious culture. The idea that Navajos talk about, walking with God and walking in beauty, I was raised to think that way, that one walks with God.

ESH: That’s really lovely. And I think it speaks to the way that around the world, there are these spiritual traditions within which nature and the landscape—there is something so spiritual about that. And that is certainly not uncommon. You see that in so many traditions around the world.

KWS: Our land is all we have; our Earth is all we have. And I think, what is more spiritual than that, because that is who we are. We are people of this Earth, this planet. One of the things I want people to see when they view my work is the beauty and the inherent spirituality of our world. I mean, it’s up to us to save it, and it’s in dire straits right now. We’re really destroying our planet, and that has to stop. We have to stop. So, I hope that my work encourages people to recognize the beauty of our world, and that we must protect it.

ESH: To return to this term “feminism.” Some Native women in the in the 1970s, and also today, reject the term and the tenets of feminism, or mainstream feminism. They view feminism as being incompatible, in some ways, with Indigenous customs, customs in which, as we’ve discussed, women have always been respected for their community roles, seemingly negating some feminist concerns. You were involved in the feminist movement. You certainly don’t shy away from this word. You identify as a feminist. You may have already answered this question, but I would love to hear you speak further on this—are there any tensions between feminist concerns and Indigenous concerns for you?

KWS: Not for me, but I recognize that there are for other women, because they feel that in their culture, they are honored and supported. I have to tell you, quite honestly, if I ever had any kind of discrimination, I think the primary discrimination was the fact that I’m a woman. Now, it isn’t the kind of thing that people say to you, “Oh, dear, we’re not going to show you.” But I did have a dealer say, “Oh, we have too many women on the roster already.” But there has always been a “Oh, you’re married?” “Oh, you have children?” As if neither are appropriate if you’re a painter. There was discrimination, I’m certain of it, and it was because I was a woman. I do not think it was because I was an Indian. Now, again, people are not going to tell you if they’re discriminating against you because you’re an Indian or whatever. So, there may have been. I do know, in my heart of hearts, that had I been a man, I would have been showing in major galleries fifty years ago. It’s just the way it was. Just the way it was. For a long time.

ESH: I think that rings true for so many women.

KWS: Oh, everyone I talk to.

ESH: Indigenous and otherwise.

KWS: There’s not too many of us left who are my age. In fact, a couple of important women artists just passed—Audrey Flack and . . . God, I’m sorry, names just leave me. But the point is that, yes, everyone who was of my era says the same thing.

ESH: And I think that is why feminism is so important, or can be so important, in combating some of the ways things have been and shouldn’t have been in in the art world.

KWS: You know, things have improved so much, so much. It’s a different world for young women today, totally different world. I came of age in the 1950s, a different world. And when you start thinking about it, enumerating it, it just goes on and on, the differences, but it’s certainly a better time for a young artist, to be a young female artist. In fact, whatever gender is safer today.

ESH: That leads to one of my last questions here, which is what advice do you have for the next generation? Speaking from your position, you’ve seen so much, what advice do you have for the next generation of artists who are seeking to produce feminist focused works, or works having to do with identity, gender or otherwise?

KWS: I think people just have to be who they are and be honest. Be as honest as you can. Be straightforward and love your neighbor, be kind to others, and respect other people’s views the way you expect your views to be respected. And enjoy it. Enjoy yourself.

ESH: Another standard Feminist Interview Project question that I’ll ask you as we wind down here: what is the ultimate relationship between feminism and your artistic practice?

KWS: I have no idea how to answer that.

ESH: It’s another tough one.

KWS: Well, I really don’t. Because, as I said, I think that being oneself and being honest in one’s art, is what I’ve tried to do. And I would think that the feminist aspect of my life is going to show in the art, whatever I do.

ESH: And lastly, as we’ve mentioned, had you been a man, this would have likely happened sooner, but your work is now gaining great recognition. You are being shown in an incredible number of group and solo shows. You’re represented in major collections. Do you have any upcoming projects on the horizon that you would like to share with the AJO readers?

KWS: Yes, I had a show at the New York Historical Society [Kay WalkingStick / Hudson River School], which had a wonderful attendance and was written about in so many wonderful places with great enthusiasm. And it was nice for me because I was showing my work with Hudson River School painters. So here I was showing with these nineteenth-century art stars. So that was a thrill. And that is going to the Addison Gallery, in Andover, so it’s all going to be up again, and I’m looking forward to that show.

ESH: It’s great that that show is traveling. When it first came out, it was referenced everywhere, every art publication that I subscribe to. It got great attention and looks like a fantastic show. Attitudes and parameters do seem to be changing, and hopefully that’s a trajectory that continues.

KWS: I think that the reason that my work has gotten so much recognition in the last, oh, really, ten years is that I had a retrospective at the Smithsonian that opened in 2015. Since that time, there’s been a lot of interest in my work. And a few years ago, two or three years ago, Hales Gallery started showing my work, and Stuart Morrison has really seen to it that my work was in a lot of art fairs and things like that.

But politically there’s been a lot of activity to accept Indigenous artists into the canon, and I think that my success . . . I mean, I’m doing the same paintings I always did. I’m not a better painter now than I was thirty years ago, to tell the truth. I would like to think I am, but I’m not. But I think that because of the political landscape that has changed, the political viewpoint of accepting Indigenous artists has altered completely. And because of that, those of us who are Native artists are showing more and are being accepted into the mainstream—which, by the way, was always my goal, to somehow bring us into the mainstream. It’s a big deal, a big change for me. But really, the painting is no better. It isn’t the painting that makes the difference. It’s the political and social surroundings, the ambiances even. We’re surrounded by this acceptance that was not there before. I had people say, “Well, you know, if you were in the southwest, I could show your work, but I can’t show that here,” and things like that. Implying that it’s because I was an Indian that they couldn’t show it. Now, people want to show Indigenous artists. Big difference. It’s amazing.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kay WalkingStick (she/her) is a Cherokee artist whose career spans six decades, during which time she has had over thirty solo shows across the US and internationally. Her practice addresses critical issues pertaining to Indigeneity, sovereignty, colonization, decolonization, gender, sexuality, and feminism, and her work is represented in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MoMA, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, among many others. She is represented by Hales Gallery, NYC. WalkingStick is a Professor Emerita at Cornell University, where she taught painting and drawing for seventeen years.

Elizabeth “Betsy” S. Hawley, PhD (she/her) is an art historian, writer, and curator specializing in modern and contemporary art and art of the Americas. Her research often focuses on Native North American art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and other areas of expertise include ecocritical art, feminist/women’s art, political/activist art, and art of the American West.

- WalkingStick had two children with her first husband, R. Michael Echols. Echols died in 1989. In 2013, WalkingStick married Dirk Bach, an artist and art historian. ↩

- The artist received a Danforth Foundation Graduate Fellowship for Women in 1973. ↩

- The American Indian Movement (AIM) was founded in 1968, and remained active in the 1970s and 1980s. The group split in the early 1990s due to internal tensions, but AIM chapters are still active today. ↩

- MoMA acquired You’re an Indian? in 2022. ↩

- Parfleche bags are typically produced by women in Plains communities, and the bags are usually made of processed rawhide decorated with painted geometric designs. ↩

- Gaylord Torrence, American Indian Parfleche: A Tradition of Abstract Painting (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994). ↩